Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) is an internationally agreed-upon standard managed by the United Nations that was set up to replace the assortment of hazardous material classification and labelling schemes previously used around the world. Core elements of the GHS include standardized hazard testing criteria, universal warning pictograms, and safety data sheets which provide users of dangerous goods relevant information with consistent organization. The system acts as a complement to the UN numbered system of regulated hazardous material transport. Implementation is managed through the UN Secretariat. Although adoption has taken time, as of 2017, the system has been enacted to significant extents in most major countries of the world.[1] This includes the European Union, which has implemented the United Nations' GHS into EU law as the CLP Regulation, and United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards.[2]

History

[edit]Before the GHS was created and implemented, there were many different regulations on hazard classification in use in different countries, resulting in multiple standards, classifications and labels for the same hazard. Given the $1.7 trillion per year international trade in chemicals requiring hazard classification, the cost of compliance with multiple systems of classification and labeling is significant. Developing a worldwide standard accepted as an alternative to local and regional systems presented an opportunity to reduce costs and improve compliance.[3]

The GHS development began at the 1992 Rio Conference on Environment and Development by the United Nations,[4] also called Earth Summit (1992), when the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), various governments, and other stakeholders agreed that "A globally harmonized hazard classification and compatible labelling system, including material safety data sheets and easily understandable symbols, should be available if feasible, by the year 2000".[5]

The universal standard for all countries was to replace all the diverse classification systems; however, it is not a compulsory provision of any treaty. The GHS provides a common infrastructure for participating countries to use when implementing a hazard classification and Hazard Communication Standard.[3]

Hazard classification

[edit]The GHS classification system defines and classifies the physical, health, and/or environmental hazards of a substance. Each category within the classifications has associated pictograms to be used when applied to a material or mixture.

Physical hazards

[edit]As of the 10th revision of the GHS,[6] substances or articles are assigned to 17 different hazard classes largely based on the United Nations Dangerous Goods System.[7]

- Explosives are assigned to one of four subcategories depending on the type of hazard they present, similar to the categories used in the UN Dangerous Goods System. Category 1 includes explosives not covered by the 6 Dangerous Goods categories.

- Flammable gases are assigned to one of 3 categories based on reactivity:

- Category 1A includes extremely flammable gases ignitable at 20 °C and standard pressure of 101.3 kPa, pyrophoric gases, and chemically unstable gases that may react in the absence of oxygen.

- Category 1B gases meet the flammability criteria of 1A, but are not pyrophoric or chemically unstable and have a lower flammability limit in air.

- Category 2 includes gases which do not meet the above criteria but otherwise are flammable at 20 °C and standard pressure.

- Aerosols and chemicals under pressure are categorized into one of 3 categories, but may be additionally classified as explosives or flammable gases if material properties match the previous classifications. From category 1 to 3, aerosols are classified as most to least flammable. All aerosols under these categories carry a bursting hazard.

- Oxidizing gases are any gaseous substance which contribute to combustion of other materials more than air would. There is only one category of oxidizing gases.

- Gases under pressure are categorized as compressed, liquefied, refrigerated, or dissolved gases, all of which may explode when heated or (in the case of refrigerated gases) cause cryogenic injury, such as frostbite.

- Flammable liquids are categorized by flammability, from Category 1 with flash point < 23 °C and initial boiling point < 35 °C to Category 4 with flash point > 60 °C and < 93 °C.

- Flammable solids are classified as solid substances which are readily combustible or may contribute to a fire through friction, and ignitable metal powders. They are placed into Category 1 if a fire is not stopped by wetting the substance, and Category 2 if wetting stops the fire for at least 4 minutes.

- Self-reactive substances and mixtures are liable to detonate or combust without the participation of air and are placed into 7 categories from A to G with decreasing reactivity.

- Pyrophoric liquids are liable to ignite after 5 minutes of coming in contact with air.

- Pyrophoric solids follow the same criteria as pyrophoric liquids.

- Self-heating substances, which differ from self-reactive substances in that they will only ignite in large quantities (kilograms) and after a long duration of time (hours or days). Category 1 is reserved for samples which self-heat in small quantities (25 mm2), and all other self-heating substances that only heat in large quantities are listed under Category 2.

- Substances and mixtures which, in contact with water, emit flammable gases are categorized from 1 to 3 based on the ignitability of the gas emitted.

- Oxidizing liquids contribute to the combustion of other materials and are categorized from 1 to 3 in decreasing oxidizing potential.

- Oxidizing solids follow the same criteria as oxidizing liquids.

- Organic peroxides are unstable substances or mixtures and may be derivatives of hydrogen peroxide. They are categorized from A to G based on inherent ability to explode or otherwise combust.

- Corrosive to metals materials may damage or destroy metals, based on tests done on aluminum and steel. The corrosion rate must be greater than 6.25 mm/year on either material to qualify under this classification.

- Desensitized explosives are materials that would otherwise be classified as explosive, but have been stabilized, or phlegmatized, to be exempted from said class.

Health hazards

[edit]- Acute toxicity includes five GHS categories from which the appropriate elements relevant to transport, consumer, worker and environment protection can be selected. Substances are assigned to one of the five toxicity categories on the basis of LD50 (oral, dermal) or LC50 (inhalation).

- Skin corrosion means the production of irreversible damage to the skin following the application of a test substance for up to 4 hours. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to a single harmonized corrosion category. Skin irritation means the production of reversible damage to the skin following the application of a test substance for up to 4 hours. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to a single irritant category. For those authorities, such as pesticide regulators, wanting more than one designation for skin irritation, an additional mild irritant category is provided.

- Serious eye damage means the production of tissue damage in the eye, or serious physical decay of vision, following application of a test substance to the front surface of the eye, which is not fully reversible within 21 days of application. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to a single harmonized category. Eye irritation means changes in the eye following the application of a test substance to the front surface of the eye, which are fully reversible within 21 days of application. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to a single harmonized hazard category. For authorities, such as pesticide regulators, wanting more than one designation for eye irritation, one of two subcategories can be selected, depending on whether the effects are reversible in 21 or 7 days.

- Respiratory sensitizer means a substance that induces hypersensitivity of the airways following inhalation of the substance. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to one hazard category. Skin sensitizer means a substance that will induce an allergic response following skin contact. The definition for "skin sensitizer" is equivalent to "contact sensitizer". Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to one hazard category.

- Germ cell mutagenicity means an agent giving rise to an increased occurrence of mutations in populations of cells and/or organisms. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to one of two hazard categories. Category 1 has two subcategories.

- Carcinogenicity means a chemical substance or a mixture of chemical substances that induce cancer or increase its incidence. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to one of two hazard categories. Category 1 has two subcategories.

- Reproductive toxicity includes adverse effects on sexual function and fertility in adult males and females, as well as developmental toxicity in offspring. Substances and mixtures with reproductive and/or developmental effects are assigned to one of two hazard categories, 'known or presumed' and 'suspected'. Category 1 has two subcategories for reproductive and developmental effects. Materials which cause concern for the health of breastfed children have a separate category: effects on or via Lactation.

- Specific target organ toxicity (STOT) [8] category distinguishes between single and repeated exposure for Target Organ Effects. All significant health effects, not otherwise specifically included in the GHS, that can impair function, both reversible and irreversible, immediate and/or delayed are included in the non-lethal target organ/systemic toxicity class (TOST). Narcotic effects and respiratory tract irritation are considered to be target organ systemic effects following a single exposure. Substances and mixtures of the single exposure target organ toxicity hazard class are assigned to one of three hazard categories. Substances and mixtures of the repeated exposure target organ toxicity hazard class are assigned to one of two hazard categories.

- Aspiration hazard includes severe acute effects such as chemical pneumonia, varying degrees of pulmonary injury or death following aspiration. Aspiration is the entry of a liquid or solid directly through the oral or nasal cavity, or indirectly from vomiting, into the trachea and lower respiratory system. Substances and mixtures of this hazard class are assigned to one of two hazard categories this hazard class on the basis of viscosity.

Environmental hazards

[edit]- Acute aquatic toxicity indicates the intrinsic property of a material of causing injury to an aquatic organism in a short-term exposure. Substances and mixtures of this hazard class are assigned to one of three toxicity categories on the basis of acute toxicity data: LC50 (fish) or EC50 (crustacean) or ErC50 (for algae or other aquatic plants). These acute toxicity categories may be subdivided or extended for certain sectors.

- Chronic aquatic toxicity indicates the potential or actual properties of a material to cause adverse effects to aquatic organisms during exposures that are determined in relation to the lifecycle of the organism. Substances and mixtures in this hazard class are assigned to one of four toxicity categories on the basis of acute data and environmental fate data: LC50 (fish), EC50 (crustacea) ErC50 (for algae or other aquatic plants), and degradation or bioaccumulation.

Classification of mixtures

[edit]The GHS approach to the classification of mixtures for health and environmental hazards uses a tiered approach and is dependent upon the amount of information available for the mixture itself and for its components. Principles that have been developed for the classification of mixtures, drawing on existing systems such as the European Union (EU) system for classification of preparations laid down in Directive 1999/45/EC.[9] The process for the classification of mixtures is based on the following steps:

- Where toxicological or ecotoxicological test data are available for the mixture itself, the classification of the mixture will be based on that data;

- Where test data are not available for the mixture itself, then the appropriate bridging principles should be applied, which uses test data for components and/or similar mixtures;

- If (1) test data are not available for the mixture itself, and (2) the bridging principles cannot be applied, then use the calculation or cutoff values described in the specific endpoint to classify the mixture.

Substitute substances

[edit]Companies are encouraged to replace hazardous substances with substances featuring a reduced health risk. As an assistance to assess possible substitute substances, the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the German Social Accident Insurance (IFA) has developed the Column Model. On the basis of just a small amount of information on a product, substitute substances can be evaluated with the support of this table. The current version from 2020 already includes the amendments of the 12th CLP Adaptation Regulation 2019/521.[10]

Testing requirements

[edit]The GHS generally defers to the United States Environmental Protection Agency and OECD to provide and verify toxicity testing requirements for substances or mixtures.[11][12] Overall, the GHS criteria for determining health and environmental hazards are test method neutral, allowing different approaches as long as they are scientifically sound and validated according to international procedures and criteria already referred to in existing systems. Test data already generated for the classification of chemicals under existing systems should be accepted when classifying these chemicals under the GHS, thereby avoiding duplicative testing and the unnecessary use of test animals.[6]

For physical hazards, the test criteria are linked to specific UN test methods.[6]

Hazard communication

[edit]Per GHS, hazards need to be communicated:[11][6]: 4

- in more than one form (for example, placards, labels or Safety Data Sheets),

- with hazard statements and precautionary statements,

- in an easily comprehensible and standardized manner,

- consistent with other statements to reduce confusion, and

- taking into account all existing research and any new evidence.

Comprehensibility is a significant consideration in GHS implementation. The GHS Purple Book includes a comprehensibility-testing instrument in Annex 6. Factors that were considered in developing the GHS communication tools include:[11]

- Different philosophies in existing systems on how and what should be communicated;

- Language differences around the world;

- Ability to translate phrases meaningfully;

- Ability to understand and appropriately respond to pictograms.

GHS label elements

[edit]

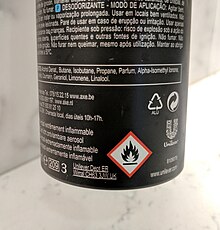

The standardized label elements included in the GHS are:[13]: 12

- Symbols (GHS hazard pictograms): Convey health, physical and environmental hazard information, assigned to a GHS hazard class and category. Pictograms include the harmonized hazard symbols plus other graphic elements, such as borders, background patterns or cozers and substances which have target organ toxicity.[14] Also, harmful chemicals and irritants are marked with an exclamation mark, replacing the European saltire. Pictograms will have a black symbol on a white background with a red diamond frame. For transport, pictograms will have the background, symbol and colors currently used in the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods. Where a transport pictogram appears, the GHS pictogram for the same hazard should not appear.

- Signal word: "Danger" or "Warning" will be used to emphasize hazards and indicate the relative level of severity of the hazard, assigned to a GHS hazard class and category. Some lower level hazard categories do not use signal words. Only one signal word corresponding to the class of the most severe hazard should be used on a label.

- GHS hazard statements: Standard phrases assigned to a hazard class and category that describe the nature of the hazard. An appropriate statement for each GHS hazard should be included on the label for products possessing more than one hazard.

The additional label elements included in the GHS are:

- GHS precautionary statements: Measures to minimize or prevent adverse effects. There are four types of precautionary statements covering: prevention, response in cases of accidental spillage or exposure, storage, and disposal. The precautionary statements have been linked to each GHS hazard statement and type of hazard.

- Product identifier (ingredient disclosure): Name or number used for a hazardous product on a label or in the SDS. The GHS label for a substance should include the chemical identity of the substance. For mixtures, the label should include the chemical identities of all ingredients that contribute to acute toxicity, skin corrosion or serious eye damage, germ cell mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity, skin or respiratory sensitization, or Specific Target Organ Toxicity (STOT), when these hazards appear on the label.

- Supplier identification: The name, address and telephone number should be provided on the label.

- Supplemental information: Non-harmonized information on the container of a hazardous product that is not required or specified under the GHS. Supplemental information may be used to provide further detail that does not contradict or cast doubt on the validity of the standardized hazard information.[6]: 25

GHS label format

[edit]The GHS includes directions for application of the hazard communication elements on the label. In particular, it specifies for each hazard, and for each class within the hazard, what signal word, pictogram, and hazard statement should be used. The GHS hazard pictograms, signal words and hazard statements should be located together on the label. The actual label format or layout is not specified. National authorities may choose to specify where information should appear on the label, or to allow supplier discretion in the placement of GHS information.

The diamond shape of GHS pictograms resembles the shape of signs mandated for use by the United States Department of Transportation. To address this, in cases where a pictogram would be required by both the Department of Transportation and the GHS indicating the same hazard, only the Transportation pictogram is to be used.[15]

Safety data sheet

[edit]Safety data sheets or SDS are specifically aimed at use in the workplace. Safety data sheets take precedence over and are intended to replace the previously used material safety data sheets (MSDS),[16] which did not have a standard layout and section format. It should provide comprehensive information about the chemical product that allows employers and workers to obtain concise, relevant and accurate information in perspective to the hazards, uses and risk management of the chemical product in the workplace. Compared to the differences found between manufacturers in MSDS, SDS have specific requirements to include the following headings in the order specified:[17]

- Identification

- Hazard(s) identification

- Composition/ information on ingredients

- First-aid measures

- Fire-fighting measures

- Accidental release measures

- Handling and storage

- Exposure control/ personal protection

- Physical and chemical properties

- Chemical stability and reactivity

- Toxicological information

- Ecological information

- Disposal considerations

- Transport information

- Regulatory information

- Other information

The primary difference between the GHS and previous international industry recommendations is that sections 2 and 3 have been reversed in order. The GHS SDS headings, sequence, and content are similar to the ISO, European Union and ANSI MSDS/SDS requirements. A table comparing the content and format of a MSDS/SDS versus the GHS SDS is provided in Appendix A of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) GHS guidance.[18]

Training

[edit]Current training procedures for hazard communication in the United States are more detailed than the GHS training recommendations.[3] Training is a key component of the overall GHS approach. Employees and emergency responders must be trained on all program elements, though there has been confusion among these groups of workers in the implementation process regarding which training elements have changed and are required to maintain regulatory compliance.[19]

Implementation

[edit]The United Nations goal was for broad international adoption of the system, and as of 2017, the GHS had been adopted to varying degrees in many major countries. Smaller economies continue to develop regulations to implement the GHS throughout the 2020s.[20]

GHS adoption by country

[edit]- Australia: In 2012, adopted regulation for GHS implementation, setting January 1, 2017 as the GHS implementation deadline.[21]

- Brazil: Established an implementation deadline of February 2011 for substances and June 2015 for mixtures.[22]

- Canada: GHS was incorporated into WHMIS 2015 as of February 2015.[23] In 2023 the WHMIS requirements were updated to align with the 7th revised edition and certain provisions of the 8th revised edition of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS).[24]

- China: Established implementation deadline of December 1, 2011.[25]

- Colombia: Following the issuance of Resolution 0773/2021 on April 9, 2021, Colombia enforced the implementation of the GHS, with deadlines taking effect April 7, 2023 for pure substances, with mixtures following the same protocols the following year.[26]

- European Union: The deadline for substance classification was December 1, 2010 and for mixtures it was June 1, 2015, per regulation for GHS implementation on December 31, 2008.[27]

- Japan: Established deadline of December 31, 2010 for products containing one of 640 designated substances.[25]

- South Korea: Established the GHS implementation deadline of July 1, 2013.[25]

- Malaysia: Deadline for substance and mixture was April 17, 2015 per its Industry Code of Practice on Chemicals Classification and Hazard Communication (ICOP) on 16 April 2014.[28]

- Mexico: GHS has been incorporated into the Official Mexican Standard as of 2015.[29]

- Pakistan: Country does not a single streamlined system for chemical labeling, although there are many rules in place. The Pakistani government has requested assistance in developing future regulations to implement GHS.[30]

- Philippines: The deadline for substances and mixtures was March 14, 2015, per Guidelines for the Implementation of GHS in Chemical Safety Program in the Workplace in 2014.[31]

- Russian Federation: GHS was approved for optional use as of August 2014. Manufacturers may continue using non-GHS Russian labels through 2021, after which compliance with the system is compulsory.[32]

- Taiwan: Full GHS implementation was scheduled for 2016 for all hazardous chemicals with physical and health hazards.[33]

- Thailand: The deadline for substances was March 13, 2013. The deadline for mixtures was March 13, 2017.[34]

- Turkey: Published Turkish CLP regulation and SDS regulation in 2013 and 2014 respectively. The deadline for substance classification was June 1, 2015, for mixtures, it was June 1, 2016.[35]

- United Kingdom: Implemented under EU directive by REACH regulations, this may be subject to change due to Brexit.

- United States: GHS compliant labels and SDSs are required for many applications including laboratory chemicals, commercial cleaning agents, and other workplace cases regulated by previous US Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) standards.[36] First widespread implementation set by OSHA was on March 26, 2012, requiring manufacturers to adopt the standard by June 1, 2015, and product distributors to adopt the standard by December 1, 2015. Workers had to be trained by December 1, 2013.[37][38] In the US, GHS labels are not required on most hazardous consumer grade products (ex. laundry detergent) however some manufacturers which also sell the same product in Canada or Europe include GHS compliant warnings on these products too. The US Consumer Product Safety Commission is not opposed to this and has been evaluating the possibility of incorporating elements of GHS into future consumer regulations.[39]

- Uruguay: regulation approved in 2011, setting December 31, 2012 as deadline for pure substances and December 31, 2017, for compounds.[40]

- Vietnam: The deadline for substances was March 30, 2014. The deadline for mixtures was March 30, 2016.[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "GHS implementation - Transport - UNECE". www.unece.org. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "HCS/HazCom Final Rule Regulatory Text". U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c "A Guide to The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals" (PDF). Occupational Safety and Health Administration, United States of America. OSHA, U.S.A. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Health and Safety Executive (n.d.). "UK Government HSE website". UK Government.

- ^ "GHS: What's Next? Visual.ly". visual.ly. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e "GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELLING OF CHEMICALS (GHS)" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. July 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods - Model Regulations". rev. 9. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. pp. 59–60. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ "Part 3 Health Hazards" (PDF). Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS). Second revised edition. United Nations. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Directive 1999/45/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 1999 concerning the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the classification, packaging and labelling of dangerous preparations". EUR-Lex. May 31, 1999. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "The GHS Column Model as an aid to selecting substitute substances" (in English and German). Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the German Social Accident Insurance. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ a b c Winder, Chris; Azzi, Rola; Wagner, Drew (October 2005). "The development of the globally harmonized system (GHS) of classification and labelling of hazardous chemicals". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 125 (1–3): 29–44. Bibcode:2005JHzM..125...29W. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.05.035. PMID 16039045.

- ^ "The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS): Implementation Planning Issues for the Office of Pesticide Programs" (PDF). www.epa.gov. 7 July 2004. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Guidance on Labelling and Packaging in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008" (PDF). ECHA. April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "GHS pictograms - Transport - UNECE". www.unece.org. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Summary of 29 CFR 1910", Industrial Safety and Health for People-Oriented Services, CRC Press, pp. 117–138, 2008-10-24, doi:10.1201/9781420053852-11, ISBN 978-0-429-14487-5, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ "Hazard Communication Standard: Safety Data Sheets" (PDF). U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. February 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "Understanding The GHS SDS Sections". Archived from the original on 2019-12-26. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ^ "Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals - GHS". www.osha.gov. Appendix A. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Koshy, Koshy; Presutti, Michael; Rosen, Mitchel A. (2015-03-01). "Implementing the Hazard Communication Standard final rule: Lessons learned". Journal of Chemical Health & Safety. 22 (2): 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.jchas.2014.10.002. ISSN 1871-5532.

- ^ "GHS implementation by country" (PDF). unece.org. November 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Hazardous chemicals". Archived from the original on 2012-11-16.

- ^ "Implementation of GHS in Brazil" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "WHMIS Transition". Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ "Amendments to the Hazardous Products Regulations". Government of Canada. March 27, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c "GHS in China, Korea and Japan". Archived from the original on 2016-04-13.

- ^ Wen, Theory (20 April 2023). "Colombia Enforces GHS Implementation in Workplace". ChemLinked. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "CLP/GHS - Classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures". European Commission. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14.

- ^ "GHS in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "Diario Oficial de la Federación". Diario Oficial de la Federación (in Spanish). 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan Industrial Label Review Nexreg". www.nexreg.com. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "GHS Implementation in Philippines", ChemSafetyPRO, 2016, archived from the original on 2016-09-15

- ^ "GHS in Russia". www.chemsafetypro.com. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "GHS in Taiwan". Archived from the original on 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "GHS in Thailand". Archived from the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "GHS in Turkey". Archived from the original on 2016-08-07.

- ^ "FAQs on Hazard Communication Standard, GHS Labels, Safety Data Sheets, HazCom Training". www.jjkeller.com. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "Hazard Communication". OSHA. Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "Hazard Communication System Final Rule - Fact Sheet". OSHA. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29.

- ^ "Policy of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS)". CPSC.gov. 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "MODIFICACION DEL DECRETO 307/009. ETIQUETADO DE PRODUCTOS QUIMICOS. SISTEMA GLOBALMENTE ARMONIZADO" (in Spanish). IMPO. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ "GHS Implementation in Vietnam". 2016-01-05. Archived from the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fagotto, Elena; Fung, Archon (2003), "Improving Workplace Hazard Communication", Issues in Science & Technology, 19 (2): 63, doi:10.1002/pam.20160, archived from the original on 2009-01-29, retrieved 2009-03-08

- Obadia, I. (2003), "ILO Activities in the Area of Chemical Safety", Toxicology, 190 (1–2): 105–15, Bibcode:2003Toxgy.190..105O, doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00200-2, PMID 12909402

- A Guide to the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS), Occupational Health and Safety Administration, 2006, archived from the original on July 2, 2007, retrieved July 13, 2007

- Smith, Sandy (2007), "GHS: A Short Acronym for a Big Idea", Occupational Hazards, 69 (5): 6

- Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2007, retrieved July 13, 2007

KSF

KSF