Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (M–Z)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 96 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 96 min

This glossary of cellular and molecular biology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of cell biology, molecular biology, and related disciplines, including molecular genetics, biochemistry, and microbiology.[1] It is split across two articles:

- Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (0–L) lists terms beginning with numbers and those beginning with the letters A through L.

- Glossary of cellular and molecular biology (M–Z) (this page) lists terms beginning with the letters M through Z.

This glossary is intended as introductory material for novices (for more specific and technical detail, see the article corresponding to each term). It has been designed as a companion to Glossary of genetics and evolutionary biology, which contains many overlapping and related terms; other related glossaries include Glossary of virology and Glossary of chemistry.

M

[edit]- M phase

- See mitosis.

- macromolecule

- Any very large molecule composed of dozens, hundreds, or thousands of covalently bonded atoms, especially one with biological significance. Many important biomolecules, such as nucleic acids and proteins, are polymers consisting of a repeated series of smaller monomers; others such as lipids and carbohydrates may not be polymeric but are nevertheless large and complex molecules.

- macronucleus

- The larger of the two types of nuclei which occur in pairs in the cells of some ciliated protozoa. Macronuclei are highly polyploid and responsible for directing vegetative reproduction, in contrast to the diploid micronuclei, which have important functions during conjugation.[2]

- macrophage

- Any of a class of relatively long-lived phagocytic cells of the mammalian immune system which are activated in response to the presence of foreign materials in certain tissues and subsequently play important roles in antigen presentation, stimulating other types of immune cells, and killing or engulfing parasitic microorganisms, diseased cells, or tumor cells.[3]

- major groove

- map-based cloning

- See positional cloning.

- massively parallel sequencing

- medical genetics

- The branch of medicine and medical science that involves the study, diagnosis, and management of hereditary disorders, and more broadly the application of knowledge about human genetics to medical care.

- megabase (Mb)

- A unit of nucleic acid length equal to one million (1×106) bases in single-stranded molecules or one million base pairs in duplex molecules such as double-stranded DNA.

- meiosis

- A specialized type of cell division that occurs exclusively in sexually reproducing eukaryotes, during which DNA replication is followed by two consecutive rounds of division to ultimately produce four genetically unique haploid daughter cells, each with half the number of chromosomes as the original diploid parent cell. Meiosis only occurs in cells of the sex organs, and serves the purpose of generating haploid gametes such as sperm, eggs, or spores, which are later fused during fertilization. The two meiotic divisions, known as Meiosis I and Meiosis II, may also include various genetic recombination events between homologous chromosomes.

- meiotic spindle

- See spindle apparatus.

- melting

- The denaturation of a double-stranded nucleic acid into two single strands, especially in the context of the polymerase chain reaction.

- membrane

- A supramolecular aggregate of amphipathic lipid molecules which when suspended in a polar solvent tend to arrange themselves into structures which minimize the exposure of their hydrophobic tails by sheltering them within a ball created by their own hydrophilic heads (i.e. a micelle). Certain types of lipids, specifically phospholipids and other membrane lipids, commonly occur as double-layered sheets of molecules when immersed in an aqueous environment, which can themselves assume approximately spherical shapes, acting as semipermeable barriers surrounding a water-filled interior space. This is the basic structure of the biological membranes enclosing all cells, vesicles, and membrane-bound organelles.

- membrane protein

- Any protein that is closely associated either transiently or permanently with the lipid bilayer membrane surrounding a cell, organelle, or vesicle.[4]

- membrane-bound organelle

- An organelle or cellular compartment enclosed by its own dedicated lipid membrane, separating its interior from the rest of the cytoplasm.

- messenger RNA (mRNA)

- Any of a class of single-stranded RNA molecules which function as molecular messengers, carrying sequence information encoded in the DNA genome to the ribosomes where protein synthesis occurs. The primary products of transcription, mRNAs are synthesized by RNA polymerase, which builds a chain of ribonucleotides that complement the deoxyribonucleotides of a DNA template; in this way, the DNA sequence of a protein-coding gene is effectively preserved in the raw transcript, which is subsequently processed into a mature mRNA by a series of post-transcriptional modifications.

- metabolism

- The complete set of chemical reactions which sustain and account for the basic processes of life in all living cells,[2] especially those involving: 1) the conversion of energy from food into energy available for cellular activities; 2) the breakdown of food into simpler compounds which can then be used as substrates to build complex biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids; and 3) the degradation and excretion of toxins, byproducts, and other unusable compounds known as metabolic wastes. In a broader sense the term may include all chemical reactions occurring in living organisms, even those which are not strictly necessary for life but instead serve accessory functions. Many specific cellular activities are accomplished by metabolic pathways in which one chemical is ultimately transformed through a stepwise series of reactions into another chemical, with each reaction catalyzed by a specific enzyme. Most metabolic reactions can be subclassified as catabolic or anabolic.

- metabolite

- An intermediate or end product of metabolism, especially degradative metabolism (catabolism);[2] or any substance produced by or taking part in a metabolic reaction. Metabolites include a huge variety of small molecules generated by cells from various pathways and having various functions, including as inputs to other pathways and reactions, as signaling molecules, and as stimulators, inhibitors, and cofactors of enzymes. Metabolites may result from the degradation and elimination of naturally occurring compounds as well as of synthetic compounds such as pharmaceuticals.

- metabolome

- The complete set of small-molecule chemical compounds within a cell, organelle, or any other biological sample, including both endogenous molecules (e.g. individual amino acids and nucleotides, fatty acids, organic acids, amines, simple sugars, vitamins, antibiotics, etc.) and exogenous molecules (e.g. drugs, toxins, environmental contaminants, and other xenobiotics).

- metacentric

- (of a linear chromosome or chromosome fragment) Having a centromere positioned in the middle of the chromosome, resulting in chromatid arms of approximately equal length.[5]

- metaphase

- The stage of mitosis and meiosis that occurs after prometaphase and before anaphase, during which the centromeres of the replicated chromosomes align along the equator of the cell, with each kinetochore attached to the mitotic spindle.

- methylation

- The covalent attachment of a methyl group (–CH

3) to a chemical compound, protein, or other biomolecule, either spontaneously or by enzymatic catalysis. Methylation is one of the most widespread natural mechanisms by which nucleic acids and proteins are labelled. The methylation of nucleobases in a DNA molecule inhibits recognition of the methylated sequence by DNA-binding proteins, which can effectively silence the expression of genes. Specific residues within histones are also commonly methylated, which can change nucleosome positioning and similarly activate or repress nearby loci. The opposite reaction is demethylation. - methyltransferase

- Any of a class of transferase enzymes which catalyze the covalent bonding of a methyl group (–CH

3) to another compound, protein, or biomolecule, a process known as methylation. - MicroArray and Gene Expression (MAGE)

- A group that "aims to provide a standard for the representation of DNA microarray gene expression data that would facilitate the exchange of microarray information between different data systems".[6]

- microbody

- Any of a diverse class of small membrane-bound organelles or vesicles found in the cells of many eukaryotes, especially plants and animals, usually having some specific metabolic function and occurring in great numbers in certain specialized cell types. Peroxisomes, glyoxysomes, glycosomes, and hydrogenosomes are often considered microbodies.

- microchromosome

- A type of very small chromosome, generally less than 20,000 base pairs in size, present in the karyotypes of some organisms.

- microdeletion

- A chromosomal deletion that is too short to cause any apparent change in morphology under a light microscope, though it may still be detectable with other methods such as sequencing.

- microfilament

- A long, thin, flexible, rod-like structure composed of polymeric strands of proteins, usually actins, that occurs in abundance in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, forming part of the cytoskeleton. Microfilaments comprise the cell's structural framework. They are modified by and interact with numerous other cytoplasmic proteins, playing important roles in cell stability, motility, contractility, and facilitating changes in cell shape, as well as in cytokinesis.

- micronucleus

- The smaller of the two types of nuclei that occur in pairs in the cells of some ciliated protozoa. Whereas the larger macronucleus is polyploid, the micronucleus is diploid and generally transcriptionally inactive except for the purpose of sexual reproduction, where it has important functions during conjugation.[2]

- microRNA (miRNA)

- A type of small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecule that functions in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression, particularly RNA silencing, by base-pairing with complementary sequences in mRNA transcripts, which typically results in the cleavage or destabilization of the transcript or inhibits its translation by ribosomes.

- microsatellite

- A type of satellite DNA consisting of a relatively short sequence of tandem repeats, in which certain motifs (ranging in length from one to six or more bases) are repeated, typically 5–50 times. Microsatellites are widespread throughout most organisms' genomes and tend to have higher mutation rates than other regions. They are classified as variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) DNA, along with longer minisatellites.

- microsome

- A small intracellular vesicle derived from fragments of endoplasmic reticulum observed in cells which have been homogenized.[4]

- microspike

- See filopodium.

- microtome

- microtrabecula

- A fine protein filament of the cytoskeleton. Multiple filaments form the microtrabecular network.[2]

- microtubule

- microtubule-organizing center (MTOC)

- microvesicle

- A type of extracellular vesicle released when an evagination of the cell membrane "buds off" into the extracellular space. Microvesicles vary in size from 30–1,000 nanometres in diameter and are thought to play roles in many physiological processes, including intercellular communication by shuttling molecules such as RNA and proteins between cells.[7]

- microvillus

- A small, slender, tubular cytoplasmic projection, generally 0.2–4 micrometres long and 0.1 micrometres in diameter,[8] protruding from the surface of some animal cells and supported by a central core of microfilaments. When present in large numbers, such as on epithelial cells lining the respiratory and alimentary tracts, they form a dense brush border which presumably serves to increase each cell's absorptive surface area.[2][3]

- mid body

- The centrally constricted region that forms across the central axis of a cell during cytokinesis, constricted by the closing of the contractile ring until the daughter cells are finally separated,[2] but occasionally persisting as a tether between the two cells for as long as a complete cell cycle.[8]

- middle lamella

- In plant cells, the outermost layer of the cell wall; a continuous, unified layer of extracellular pectins which is the first layer deposited by the cell during cytokinesis and which serves to cement together the primary cell walls of adjacent cells.[4]

- Minimal information about a high-throughput sequencing experiment (MINSEQE)

- A commercial standard developed by FGED for the storage and sharing of high-throughput sequencing data.[9]

- Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)

- A commercial standard developed by FGED and based on MAGE in order to facilitate the storage and sharing of gene expression data.[10][11]

- minisatellite

- A region of repetitive, non-coding genomic DNA in which certain DNA motifs (typically 10–60 bases in length) are tandemly repeated (typically 5–50 times). In the human genome, minisatellites occur at more than 1,000 loci, especially in centromeres and telomeres, and exhibit high mutation rates and high variability between individuals. Like the shorter microsatellites, they are classified as variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) and are a type of satellite DNA.

- minor groove

- minus-strand

- See template strand.

- miRNA

- See microRNA.

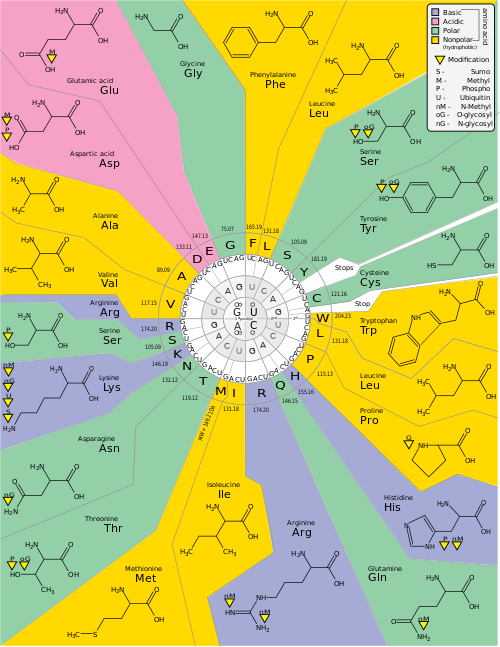

- mismatch

- An incorrect pairing of nucleobases on complementary strands of DNA or RNA; i.e. the presence in one strand of a duplex molecule of a base that is not complementary (by Watson–Crick pairing rules) to the base occupying the corresponding position in the other strand, which prevents normal hydrogen bonding between the bases. For example, a guanine paired with a thymine would be a mismatch, as guanine normally pairs with cytosine.[12]

- mismatch repair (MMR)

- missense mutation

- A type of point mutation which results in a codon that codes for a different amino acid than in the unmutated sequence. Compare nonsense mutation.

- mistranslation

- The insertion of an incorrect amino acid in a growing peptide chain during translation, i.e. the inclusion of any amino acid that is not the one specified by a particular codon in an mRNA transcript. Mistranslation may originate from a mischarged transfer RNA or from a malfunctioning ribosome.[12]

- mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

- The set of DNA molecules contained within mitochondria, usually one or more circular plasmids representing a semi-autonomous genome which is physically separate from and functionally independent of the chromosomal DNA in the cell's nucleus. The mitochondrial genome encodes many unique enzymes found only in mitochondria.

- mitochondrial fusion

- mitochondrion

- A highly pleiomorphic membrane-bound organelle found in the cytoplasm of nearly all eukaryotic cells, usually in large numbers in the form of sausage-shaped structures 5–10 micrometres in length,[8] enclosed by a double membrane, with the inner membrane infolded in an elaborate series of cristae so as to maximize surface area. Mitochondria are the primary sites of ATP synthesis, where ATP is regenerated from ADP via oxidative phosphorylation, as well as many supporting pathways, including the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain.[3] Like other plastids, mitochondria contain their own genome encoded in circular DNA molecules which replicate independently of the nuclear genome, as well as their own unique set of transcription factors, polymerases, ribosomes, transfer RNAs, and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases with which to direct transcription and translation of their genes. The majority of the structural proteins found in mitochondria are encoded by nuclear genes, however, such that mitochondria are only partially autonomous.[2] These observations suggest mitochondria evolved from symbiotic prokaryotes living inside eukaryotic cells.

- mitogen

- Any substance or stimulus that promotes or induces mitosis, or more generally which causes cells to re-enter the cell cycle.[3]

- mitophagy

- The selective degradation of mitochondria by means of autophagy; i.e. the mitochondrion initiates its own degradation. Mitophagy is a regular process in healthy populations of cells by which defective or damaged mitochondria are recycled, preventing their accumulation. It may also occur in response to the changing metabolic needs of the cell, e.g. during certain developmental stages.

- mitosis

- In eukaryotic cells, the part of the cell cycle during which the division of the nucleus takes place and replicated chromosomes are separated into two distinct nuclei. Mitosis is generally preceded by the S phase of interphase, when the cell's DNA is replicated, and either occurs simultaneously with or is followed by cytokinesis, when the cytoplasm and plasma membrane are divided into two new daughter cells. Colloquially, the term "mitosis" is often used to refer to the entire process of cell division, not just the division of the nucleus.

- mitotic index (MI)

- The proportion of cells within a sample which are undergoing mitosis at the time of observation, typically expressed as a percentage or as a value between 0 and 1. The number of cells dividing by mitosis at any given time can vary widely depending on organism, tissue, developmental stage, and culture media, among other factors.[2]

- mitotic recombination

- The abnormal exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes during mitosis (as opposed to meiosis, where it occurs normally). Homologous recombination during mitosis is relatively uncommon; in the laboratory, it can be induced by exposing dividing cells to high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as X rays. As in meiosis, it can separate heterozygous alleles and thereby propagate potentially significant changes in zygosity to daughter cells, though unless it occurs very early in development this often has little or no phenotypic effect, since any phenotypic variance shown by mutant lineages arising in terminally differentiated cells is generally masked or compensated for by neighboring wild-type cells.[2]

- mitotic rounding

- The process by which most animal cells undergo an overall change in shape during or preceding mitosis, abandoning the various complex or elongated shapes characteristic of interphase and rapidly contracting into a rounded or spherical morphology that is more conducive to cell division. This phenomenon has been observed both in vivo and in vitro.

- mitotic segregation

- mitotic spindle

- See spindle apparatus.

- mixoploidy

- The presence of more than one different ploidy level, i.e. more than one number of sets of chromosomes, in different cells of the same cellular population.[12]

- mobile genetic element (MGE)

- Any genetic material that can move between different parts of a genome or be transferred from one species or replicon to another within a single generation. The many types of MGEs include transposable elements, bacterial plasmids, bacteriophage elements which integrate into host genomes by viral transduction, and self-splicing introns.

- mobilome

- The complete set of mobile genetic elements within a particular genome, cell, species, or other taxon, including all transposons, plasmids, prophages, and other self-splicing nucleic acid molecules.

- molecular biology

- The branch of biology that studies biological activity at the molecular level, in particular the various mechanisms underlying the biological processes that occur in and between cells, including the structures, properties, synthesis, and modification of biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, their interactions with the chemical environment and with other biomolecules, and how these interactions explain the observations of classical biology (which in contrast studies biological systems at much larger scales).[13] Molecular biology relies largely on laboratory techniques of physics and chemistry to manipulate and measure microscopic phenomena. It is closely related to and overlaps with the fields of cell biology, biochemistry, and molecular genetics.

- molecular cloning

- Any of various molecular biology methods designed to replicate a particular molecule, usually a DNA sequence or a protein, many times inside the cells of a natural host. Commonly, a recombinant DNA fragment containing a gene of interest is ligated into a plasmid vector, which competent bacterial cells are then induced to uptake in a process known as transformation. The bacteria, carrying the recombinant plasmid, are then allowed to proliferate naturally in cell culture, so that each time the bacterial cells divide, the plasmids are replicated along with the rest of the bacterial genome. Any functioning gene of interest within the plasmid will be expressed by the bacterial cells, and thereby its gene products will also be cloned. The plasmids or gene products, which now exist in many copies, may then be extracted from the bacteria and purified. Molecular cloning is a fundamental tool of genetic engineering employed for a wide variety of purposes, often to study gene expression, to amplify a specific gene product, or to generate a selectable phenotype.

- molecular genetics

- A branch of genetics that employs methods and techniques of molecular biology to study the structure and function of genes and gene products at the molecular level. Contrast classical genetics.

- monad

- A haploid set of chromosomes as it exists inside the nucleus of an immature gametic cell such as an ootid or spermatid, i.e. a cell which is a product of meiosis but is not yet a mature gamete.[12]

- monocentric

- (of a linear chromosome or chromosome fragment) Having only one centromere. Contrast dicentric and holocentric.

- monoclonal

- Describing cells, proteins, or molecules descended or derived from a single clone (i.e. from the same genome or genetic lineage) or made in response to a single unique compound. Monoclonal antibodies are raised against only one antigen or can only recognize one unique epitope on the same antigen. Similarly, the cells of some tissues and neoplasms may be described as monoclonal if they are all the asexual progeny of one original parent cell.[2] Contrast polyclonal.

- monokaryotic

- (of a cell) Having a single nucleus, as opposed to no nucleus or multiple nuclei.

- monomer

- A molecule or compound which can exist individually or serve as a building block or subunit of a larger macromolecular aggregate known as a polymer.[4] Polymers form when multiple monomers of the same or similar molecular species are connected to each other by chemical bonds, either in a linear chain or a non-linear conglomeration. Examples include the individual nucleotides which form nucleic acid polymers; the individual amino acids which form polypeptides; and the individual proteins which form protein complexes.

- monoploid

- monosaccharide

- Any of a class of organic compounds which are the simplest forms of carbohydrates and the most basic structural subunits or monomers from which larger carbohydrate polymers such as disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides are built. With few exceptions, all monosaccharides are variations on the empirical formula (CH

2O)

n, where n typically ranges from 3 (trioses) to 7 (heptoses).[3] Common examples include glucose, ribose, and deoxyribose. - monosomy

- The abnormal and frequently pathological presence of only one chromosome of a normal diploid pair. It is a type of aneuploidy.

- Morpholino

- A synthetic nucleic acid analogue connecting a short sequence of nucleobases into an artificial antisense oligomer, used in genetic engineering to knockdown gene expression by pairing with complementary sequences in naturally occurring RNA or DNA molecules, especially mRNA transcripts, thereby inhibiting interactions with other biomolecules such as proteins and ribosomes. Morpholino oligomers are not themselves translated, and neither they nor their hybrid duplexes with RNA are attacked by nucleases; also, unlike the negatively charged phosphates of normal nucleic acids, the synthetic backbones of Morpholinos are electrically neutral, making them less likely to interact non-selectively with a host cell's charged proteins. These properties make them useful and reliable tools for artificially generating mutant phenotypes in living cells.[12]

- mosaicism

- The presence of two or more populations of cells with different genotypes in an individual organism which has developed from a single fertilized egg. A mosaic organism can result from many kinds of genetic phenomena, including nondisjunction of chromosomes, endoreduplication, or mutations in individual stem cell lineages during the early development of the embryo. Mosaicism is similar to but distinct from chimerism.

- motif

- Any distinctive or recurring sequence of nucleotides in a nucleic acid or of amino acids in a peptide that is or is conjectured to be biologically significant, especially one that is reliably recognized by other biomolecules or which has a three-dimensional structure that permits unique or characteristic chemical interactions such as DNA binding.[12] In nucleic acids, motifs are often short (three to ten nucleotides in length), highly conserved sequences which act as recognition sites for DNA-binding proteins or RNAs involved in the regulation of gene expression.

- motor protein

- Any protein which converts chemical energy derived from the hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates such as ATP and GTP into mechanical work in order to effect its own locomotion, by propelling itself along a filament or through the cytoplasm.[4]

- mRNA

- See messenger RNA.

- mtDNA

- See mitochondrial DNA.

- multicellular

- Composed of more than one cell. The term is especially used to describe organisms or tissues consisting of many cells descendant from the same original parent cell which work together in an organized way, but may also describe colonies of nominally single-celled organisms such as protists and bacteria which live symbiotically with each other in large groups. Contrast unicellular.

- multinucleate

- (of a cell) Having more than one nucleus within a single cell; i.e. having multiple nuclei occupying the same cytoplasm.

- multiomics

- multiple cloning site (MCS)

- mutagen

- Any physical or chemical agent that changes the genetic material (usually DNA) of an organism and thereby increases the frequency of mutations above natural background levels.

- mutagenesis

- 1. The process by which the genetic information of an organism is changed, resulting in a mutation. Mutagenesis may occur spontaneously or as a result of exposure to a mutagen.

- 2. In molecular biology, any laboratory technique by which one or more genetic mutations are deliberately engineered in order to produce a mutant gene, regulatory element, gene product, or genetically modified organism so that the functions of a genetic locus, process, or product can be studied in detail.

- mutant

- An organism, gene product, or phenotypic trait resulting from a mutation, of a type that would not be observed naturally in wild-type specimens.

- mutation

- Any permanent change in the nucleotide sequence of a strand of DNA or RNA, or in the amino acid sequence of a peptide. Mutations play a role in both normal and abnormal biological processes; their natural occurrence is integral to the process of evolution. They can result from errors in replication, chemical damage, exposure to high-energy radiation, or manipulations by mobile genetic elements. Repair mechanisms have evolved in many organisms to correct them. By understanding the effect that a mutation has on phenotype, it is possible to establish the function of the gene or sequence in which it occurs.

- mutator gene

- Any mutant gene or sequence that increases the spontaneous mutation rate of one or more other genes or sequences. Mutators are often transposable elements, or may be mutant housekeeping genes such as those that encode helicases or proteins involved in proofreading.[12]

- mutein

- A mutant protein, i.e. a protein whose amino acid sequence differs from that of the normal because of a mutation.

- muton

- The smallest unit of a DNA molecule in which a physical or chemical change can result in a mutation (conventionally a single nucleotide).[12]

N

[edit]- n orientation

- One of two possible orientations by which a linear DNA fragment can be inserted into a vector, specifically the one in which the gene maps of both fragment and vector have the same orientation.[12] Contrast u orientation.

- NAD

- See nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide.

- NADP

- See nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

- nanoinjection

- A laboratory technique involving the use of a microscopic lance or nanopipette (typically about 100 nanometres in diameter) in the presence of an electric field in order to deliver DNA or RNA directly into a cell, often a zygote or early embryo, via an electrophoretic mechanism. While submerged in a pH-buffered solution, a positive electric charge is applied to the lance, attracting negatively charged nucleic acids to its surface; the lance then penetrates the cell membrane and the electric field is reversed, applying a negative charge which repels the accumulated nucleic acids away from the lance and thus into the cell. Compare microinjection.

- nascent

- In the process of being synthesized; incomplete; not yet fully processed or mature. The term is commonly used to describe strands of DNA or RNA which are actively undergoing synthesis during replication or transcription, respectively, or sometimes a complete, fully transcribed RNA molecule before any alterations have been made (e.g. polyadenylation or RNA editing), or a peptide chain actively undergoing translation by a ribosome.[12]

- ncAA

- See non-canonical amino acid.

- ncDNA

- See non-coding DNA.

- ncRNA

- See non-coding RNA.

- negative (-) sense strand

- See template strand.

- negative control

- The inhibition or deactivation of some biological process caused by the presence of a specific molecular entity (e.g. a repressor), in the absence of which the process is not inhibited and thus can proceed normally.[14] In gene regulation, for example, a repressor may bind to an operator upstream from a coding sequence and prevent access by transcription factors and/or RNA polymerase, thereby blocking the gene's transcription. This is contrasted with positive control, in which the presence of an inducer is necessary to switch on transcription.[8]

- negative supercoiling

- The supercoiling of a double-stranded DNA molecule in the direction opposite to the turn of the double helix itself (e.g. a left-handed coiling of a helix with a right-handed turn).[8] Contrast positive supercoiling.

- next-generation sequencing (NGS)

- See massively parallel sequencing.

- nick

- A break or discontinuity in the phosphate backbone of one strand of a double-stranded DNA molecule, i.e. where a phosphodiester bond is hydrolyzed but no nucleotides are removed; such a molecule is said to be nicked. A nick is a single-strand break, where despite the break the DNA molecule is not ultimately broken into multiple fragments, which contrasts with a cut, where both strands are broken. Nicks may be caused by DNA damage or by dedicated nucleases known as nicking enzymes, which nick DNA at random or specific sites. Nicks are frequently placed by the cell as markers identifying target sites for enzyme activity, including in DNA replication, transcription, and mismatch repair, and also to release torsional stress from overwound DNA molecules, making them important in manipulating DNA topology.[8]

- nick translation

- nickase

- nicking enzyme

- Any of a class of endonuclease enzymes capable of generating a single-stranded break in a double-stranded DNA molecule, i.e. a nick, either at random or at a specific recognition sequence, by breaking a phosphodiester bond linking adjacent nucleotides.

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+, NADP)

- nitrogenous base

- Any organic compound containing a nitrogen atom that has the chemical properties of a base. Five particular nitrogenous bases – adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), thymine (T), and uracil (U) – are especially relevant to biology because they are components of nucleotides, which are the primary monomers that make up nucleic acids.

- non-canonical amino acid (ncAA)

- Any amino acid, natural or artificial, that is not one of the 20 or 21 proteinogenic amino acids encoded by the standard genetic code. There are hundreds of such amino acids, many of which have biological functions and are specified by alternative codes or incorporated into proteins accidentally by errors in translation. Many of the best known naturally occurring ncAAs occur as intermediates in the metabolic pathways leading to the standard amino acids, while others have been made synthetically in the laboratory.[15]

- non-coding DNA (ncDNA)

- Any segment of DNA that does not encode a sequence that may ultimately be transcribed and translated into a protein. In most organisms, only a small fraction of the genome consists of protein-coding DNA, though the proportion varies greatly between species. Some non-coding DNA may still be transcribed into functional non-coding RNA (as with transfer RNAs) or may serve important developmental or regulatory purposes; other regions (as with so-called "junk DNA") appear to have no known biological function.

- non-coding RNA (ncRNA)

- Any molecule of RNA that is not ultimately translated into a protein. The DNA sequence from which a functional non-coding RNA is transcribed is often referred to as an "RNA gene". Numerous types of non-coding RNAs essential to normal genome function are produced constitutively, including transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and small interfering RNA (siRNA); other non-coding RNAs (sometimes described as "junk RNA") have no known function and are likely the product of spurious transcription.

- non-coding strand

- See template strand.

- nondisjunction

- The failure of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids to segregate properly during cell division. Nondisjunction results in daughter cells that are aneuploid, containing abnormal numbers of one or more specific chromosomes. It may be caused by a variety of factors.

- non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

- nonrepetitive sequence

- Broadly, any nucleotide sequence or region of a genome that does not contain repeated sequences, or in which repeats do not comprise a majority; or any segment of DNA exhibiting the reassociation kinetics expected of a unique sequence.[12]

- nonsense mutation

- A type of point mutation which results in a premature stop codon in the transcribed mRNA sequence, thereby causing the premature termination of translation, which results in a truncated, incomplete, and often non-functional protein.

- nonsense suppressor

- A factor which can inhibit the effects of a nonsense mutation (i.e. a premature stop codon) by any mechanism, usually either a mutated transfer RNA which can bind the mutated stop codon or some kind of ribosomal mutation.[16]

- nonsynonymous mutation

- A type of mutation in which the substitution of one nucleotide base for another results, after transcription and translation, in an amino acid sequence that is different from that produced by the original unmutated gene. Because nonsynonymous mutations always result in a biological change in the organism, they are often subject to strong selection pressure. Contrast synonymous mutation.

- non-transcribed spacer (NTS)

- See spacer.

- northern blotting

- A blotting method in molecular biology used to detect RNA in a sample. Compare Southern blotting, western blotting, and eastern blotting.

- nRNA

- See nuclear RNA.

- N-terminus

- The end of a linear chain of amino acids (i.e. a peptide) that is terminated by the free amine group (–NH

2) of the first amino acid added to the chain during translation. This amino acid is said to be N-terminal. By convention, sequences, domains, active sites, or any other structure positioned nearer to the N-terminus of the polypeptide or the folded protein it forms relative to others are described as upstream. Contrast C-terminus. - nuclear cage

- nuclear DNA

- Any DNA molecule contained within the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell, most prominently the DNA in chromosomes. It is sometimes used interchangeably with genomic DNA.

- nuclear envelope

- A sub-cellular barrier consisting of two concentric lipid bilayer membranes that surrounds the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The nuclear envelope is sometimes simply called the "nuclear membrane", though the structure is actually composed of two distinct membranes, an inner membrane and an outer membrane.

- nuclear equivalence

- The principle that the nuclei of essentially all differentiated cells of a mature multicellular organism are genetically identical to each other and to the nucleus of the zygote from which they descended; i.e. they all contain the same genetic information on the same chromosomes, having been replicated from the original zygotic set with extremely high fidelity. Even though all adult somatic cells have the same set of genes, cells can nonetheless differentiate into distinct cell types by expressing different subsets of these genes. Though this principle generally holds true, the reality is slightly more complex, as mutations such as insertions, deletions, duplications, and translocations as well as chimerism, mosaicism, and various types of genetic recombination can all cause different somatic lineages within the same organism to be genetically non-identical.

- nuclear export signal (NES)

- nuclear lamina

- A fibrous network of proteins lining the inner, nucleoplasmic surface of the nuclear envelope, composed of filaments similar to those that make up the cytoskeleton. It may function as a scaffold for the various contents of the nucleus including nuclear proteins and chromosomes.[3]

- nuclear localization signal (NLS)

- An amino acid sequence within a protein which serves as a molecular signal marking the protein for transport into the nucleus, typically consisting of one or more short motifs containing positively charged amino acid residues exposed on the mature protein's surface (especially lysines and arginines). Though all proteins are translated in the cytoplasm, many whose primary biological activities occur inside the nucleus (e.g. transcription factors) require nuclear localization signals identifiable by molecular chaperones in order to cross the nuclear envelope. Contrast nuclear export signal.

- nuclear membrane

- See nuclear envelope.

- nuclear pore

- A complex of membrane proteins that creates an opening in the nuclear envelope through which certain molecules and ions are permitted to pass and thereby enter or exit the nucleus (analogous to the channel proteins in the cell membrane). The nuclear envelope typically has thousands of pores to selectively regulate the exchange of specific materials between the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm, including messenger RNAs, which are transcribed in the nucleus but must be translated in the cytoplasm, as well as nuclear proteins, which are synthesized in the cytoplasm but must return to the nucleus to serve their functions.[4][3]

- nuclear protein

- Any protein that is naturally found in or localizes to the cell's nucleus (as opposed to the cytoplasm or elsewhere).

- nuclear RNA (nRNA)

- Any RNA molecule located within a cell's nucleus, whether associated with chromosomes or existing freely in the nucleoplasm, including small nuclear RNA (snRNA), enhancer RNA (eRNA), and all newly transcribed immature RNAs, coding or non-coding, prior to their export to the cytosol (hnRNA).

- nuclear transfer

- nuclear transport

- The mechanisms by which molecules cross the nuclear envelope surrounding a cell's nucleus. Though small molecules and ions can cross the membrane freely, the entry and exit of larger molecules is tightly regulated by nuclear pores, so that most macromolecules such as RNAs and proteins require association with transport factors in order to be chaperoned across.

- nuclease

- Any of a class of enzymes capable of cleaving phosphodiester bonds connecting adjacent nucleotides in a nucleic acid molecule (the opposite of a ligase). Nucleases may nick one strand or cut both strands of a duplex molecule, and may cleave randomly or at specific recognition sequences. They are ubiquitous and imperative for normal cellular function, and are also widely employed in laboratory techniques.

- nucleic acid

- A long, polymeric macromolecule made up of smaller monomers called nucleotides which are chemically linked to one another in a chain. Two specific types of nucleic acid, DNA and RNA, are common to all living organisms, serving to encode the genetic information governing the construction, development, and ordinary processes of all biological systems. This information, contained within the order or sequence of the nucleotides, is translated into proteins, which direct all of the chemical reactions necessary for life.

- nucleic acid sequence

- The precise order of consecutively linked nucleotides in a nucleic acid molecule such as DNA or RNA. Long sequences of nucleotides are the principal means by which biological systems store genetic information, and therefore the accurate replication, transcription, and translation of such sequences is of the utmost importance, lest the information be lost or corrupted. Nucleic acid sequences may be equivalently referred to as sequences of nucleotides, nitrogenous bases, nucleobases, or, in duplex molecules, base pairs, and they correspond directly to sequences of codons and amino acids.

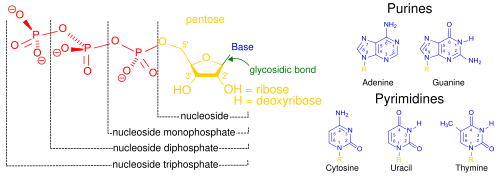

- nucleobase

- Any of the five primary or canonical nitrogenous bases – adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), thymine (T), and uracil (U) – that form nucleosides and nucleotides, the latter of which are the fundamental building blocks of nucleic acids. The ability of these bases to form base pairs via hydrogen bonding, as well as their flat, compact three-dimensional profiles, allows them to "stack" one upon another and leads directly to the long-chain structures of DNA and RNA. When writing sequences in shorthand notation, the letter N is often used to represent a nucleotide containing a generic or unidentified nucleobase.

- nucleoid

- An irregularly shaped region within a prokaryotic cell which contains most or all of the cell's genetic material, but is not enclosed by a nuclear membrane as in eukaryotes.

- nucleolin

- The primary protein of which the eukaryotic nucleolus is composed, thought to play important roles in chromatin decondensation, transcription of ribosomal RNA, and ribosome assembly.

- nucleolonema

- The central region of the nucleolus, composed of dense, convoluted fibrillar material.[2]

- nucleolus

- An organelle within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells which is composed of proteins, DNA, and RNA and serves as the site of ribosome synthesis.

- nucleoplasm

- All of the material enclosed within the nucleus of a cell by the nuclear envelope, analogous to the cytoplasm enclosed by the main cell membrane. Like the cytoplasm, the nucleoplasm is composed of a gel-like substance (the nucleosol) in which various organelles, nuclear proteins, and other biomolecules are suspended, including nuclear DNA in the form of chromosomes, the nucleolus, nuclear bodies, and free nucleotides.

- nucleoprotein

- Any protein that is chemically bonded to or conjugated with a nucleic acid. Examples include ribosomes, nucleosomes, and many enzymes.

- nucleosidase

- Any of a class of enzymes which catalyze the decomposition of nucleosides into their component nitrogenous bases and pentose sugars.[12]

- nucleoside

- An organic molecule composed of a nitrogenous base bonded to a five-carbon sugar (either ribose or deoxyribose). A nucleotide additionally includes one or more phosphate groups.

- nucleosol

- The soluble, liquid portion of the nucleoplasm (analogous to the cytosol of the cytoplasm).

- nucleosome

- The basic structural subunit of chromatin used in packaging nuclear DNA such as chromosomes, consisting of a core particle of eight histone proteins around which double-stranded DNA is wrapped in a manner akin to thread wound around a spool. The technical definition of a nucleosome includes a segment of DNA about 146 base pairs in length which makes 1.67 left-handed turns as it coils around the histone core, as well as a stretch of linker DNA (generally 38–80 bp) connecting it to an adjacent core particle, though the term is often used to refer to the core particle alone. Long series of nucleosomes are further condensed by association with histone H1 into higher-order structures such as 30-nm fibers and ultimately supercoiled chromatids. Because the histone–DNA interaction limits access to the DNA molecule by other proteins and RNAs, the precise positioning of nucleosomes along the DNA sequence plays a fundamental role in controlling whether or not genes are transcribed and expressed, and hence mechanisms for moving and ejecting nucleosomes have evolved as a means of regulating the expression of particular loci.

- nucleosome-depleted region (NDR)

- A region of a genome or chromosome in which long segments of DNA are bound by few or no nucleosomes, and thus exposed to manipulation by other proteins and molecules, especially implying that the region is transcriptionally active.

- nucleotide

- An organic molecule that serves as the fundamental monomer or subunit of nucleic acid polymers, including RNA and DNA. Each nucleotide is composed of three connected functional groups: a nitrogenous base, a five-carbon sugar (either ribose or deoxyribose), and a single phosphate group. Though technically distinct, the term "nucleotide" is often used interchangeably with nitrogenous base, nucleobase, and base pair when referring to the sequences that make up nucleic acids. Compare nucleoside.

- nucleotide sequence

- See nucleic acid sequence.

- nucleus

- A large spherical or lobular organelle surrounded by a dedicated membrane which functions as the main storage compartment for the genetic material of eukaryotic cells, including the DNA comprising chromosomes, as well as the site of RNA synthesis during transcription. The vast majority of eukaryotic cells have a single nucleus, though some cells may have more than one nucleus, either temporarily or permanently, and in some organisms there exist certain cell types (e.g. mammalian erythrocytes) which lose their nuclei upon reaching maturity, effectively becoming anucleate. The nucleus is one of the defining features of eukaryotes; the cells of prokaryotes such as bacteria lack nuclei entirely.[2]

O

[edit]- occluding junction

- ochre

- One of three stop codons used in the standard genetic code; in RNA, it is specified by the nucleotide triplet UAA. The other two stop codons are named amber and opal.

- Okazaki fragments

- Short sequences of nucleotides which are synthesized discontinuously by DNA polymerase and later linked together by DNA ligase to create the lagging strand during DNA replication. Okazaki fragments are the consequence of the unidirectionality of DNA polymerase, which only works in the 5' to 3' direction.

- oligo dT

- A short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide consisting of a sequence of repeating deoxythymidine (dT) nucleotides. Oligo dTs are commonly synthesized de novo to be used as primers for in vitro reverse transcription reactions during rtPCR techniques, where short chains of 12 to 18 thymine bases readily complement the poly(A) tails of mature messenger RNAs, allowing the selective amplification and preparation of a cDNA library from a pool of coding transcripts.[14]

- oligogene

- oligomer

- Any polymeric molecule consisting of a relatively short series of connected monomers or subunits; e.g. an oligonucleotide is a short series of nucleotides.

- oligonucleotide

- A relatively short chain of nucleic acid residues. In the laboratory, oligonucleotides are commonly used as primers or hybridization probes to detect the presence of larger mRNA molecules or assembled into two-dimensional microarrays for high-throughput sequencing analysis.

- oligosaccharide

- A polymeric carbohydrate molecule consisting of a relatively short chain of connected monosaccharides. Oligosaccharides have important functions in processes such as cell signaling and cell adhesion. Longer chains are called polysaccharides.

- oncogene

- A gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, such genes are often mutated and/or expressed at abnormally high levels.

- one gene–one polypeptide

- The hypothesis that there exists a large class of genes in which each particular gene directs the synthesis of one particular polypeptide or protein.[12] Historically it was thought that all genes and proteins might follow this rule by definition, but it is now known that many proteins are composites of different polypeptides and therefore the product of multiple genes, and also that some genes do not encode polypeptides at all but instead produce non-coding RNAs, which are never translated.

- opal

- One of three stop codons used in the standard genetic code; in RNA, it is specified by the nucleotide triplet UGA. The other two stop codons are named amber and ochre.

- open chromatin

- See euchromatin.

- open reading frame (ORF)

- The part of a reading frame that has the ability to be translated from DNA or RNA into protein; any continuous stretch of codons that contains a start codon and a stop codon.

- operator

- A regulatory sequence within an operon, typically located between the promoter sequence and the structural genes of the operon, to which an uninhibited repressor protein can bind, thereby physically obstructing RNA polymerase from initiating the transcription of adjacent cistrons.[17]

- operon

- A functional unit of gene expression consisting of a cluster of adjacent structural genes which are collectively under the control of a single promoter, along with one or more adjacent regulatory sequences such as operators which affect transcription of the structural genes. The set of genes is transcribed together, usually resulting in a single polycistronic messenger RNA molecule, which may then be translated together or undergo splicing to create multiple mRNAs which are translated independently; the result is that the genes contained in the operon are either expressed together or not at all. Regulatory proteins, including repressors and activators, usually bind specifically to the regulatory sequences of a given operon; by some definitions, the genes that code for these regulatory proteins are also considered part of the operon.

- operon network

- organelle

- A spatially distinct compartment or subunit within a cell which has a specialized function. Organelles occur in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. In the latter they are often separated from the cytoplasm by being enclosed with their own membrane bilayer (whence the term membrane-bound organelles), though organelles may also be functionally specific areas or structures without a surrounding membrane; some cellular structures which exist partially or entirely outside of the cell membrane, such as cilia and flagella, are also referred to as organelles. There are numerous types of organelles with a wide variety of functions, including the various compartments of the endomembrane system (e.g. the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus), mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, endosomes, and vacuoles, among others. Many organelles are unique to particular cell types or species.

- origin of replication (ORI)

- A particular location within a DNA molecule at which DNA replication is initiated. Origins are usually defined by the presence of a particular replicator sequence or by specific chromatin patterns.

- osmosis

- osmotic shock

- Physiological dysfunction caused by a sudden change in the concentration of dissolved solutes in the extracellular environment surrounding a cell, which provokes the rapid movement of water across the cell membrane by osmosis, either into or out of the cell. In a severely hypertonic environment, where extracellular solute concentrations are extremely high, osmotic pressure may force large quantities of water to move out of the cell (plasmolysis), leading to its desiccation; this may also have the effect of inhibiting transport of solutes into the cell, thus denying it the substrates necessary to sustain normal cellular activities. In a severely hypotonic environment, where extracellular solute concentrations are much lower than intracellular concentrations, water is forced to move into the cell (turgescence), causing it to swell in size and potentially burst, or triggering apoptosis.

- outron

- A sequence near the 5'-end of a primary mRNA transcript that is removed by a special form of splicing during post-transcriptional processing. Outrons are located entirely outside of the transcript's coding sequences, unlike introns.

- overexpression

- An abnormally high level of gene expression which results in an excessive number of copies of one or more gene products. Overexpression produces a pronounced gene-related phenotype.[18][19]

- oxidative phosphorylation

- oxidative stress

- oxygen cascade

- The flow of oxygen from environmental sources (e.g. the air in the atmosphere) to the mitochondria of a cell, where oxygen atoms participate in biochemical reactions that result in the oxidation of energy-rich substrates such as carbohydrates in a process known as aerobic respiration.

P

[edit]- p53

- A class of regulatory proteins encoded by the TP53 gene in vertebrates which bind DNA and regulate gene expression in order to protect the genome from mutation and block progression through the cell cycle if DNA damage does occur.[4] It is mutated in more than 50% of human cancers, indicating it plays a crucial role in preventing cancer formation.

- pachynema

- In meiosis, the third of five substages of prophase I, following zygonema and preceding diplonema. During pachynema, the synaptonemal complex facilitates crossing over between the synapsed homologous chromosomes, and the centrosomes begin to move apart from each other.[12]

- palindromic sequence

- A nucleic acid sequence of a double-stranded DNA or RNA molecule in which the unidirectional sequence (e.g. 5' to 3') of nucleobases on one strand matches the sequence in the same direction (e.g. 5' to 3') on the complementary strand. In other words, a sequence is said to be palindromic if it is equal to its own reverse complement. Palindromic motifs are common recognition sites for restriction enzymes.

- paracellular transport

- The transfer of substances across an epithelium by passing through the extracellular space between cells, in contrast to transcellular transport, where substances travel through cells by crossing the intracellular cytoplasm.

- paracrine

- Describing or relating to a class of agonist signaling molecules produced and secreted by regulatory cells into the extracellular environment and then transported by passive diffusion to target cells other than those which produced them. The term may refer to the molecules themselves, sometimes called paramones, to the cells that produce them, or to signaling pathways which rely on them.[14] Compare autocrine, endocrine, and juxtacrine.

- parent cell

- The original or ancestral cell from which a given set of descendant cells, known as daughter cells, have divided by mitosis or meiosis.

- passenger

- A DNA fragment of interest designed to be spliced into a 'vehicle' such as a plasmid vector and then cloned.[12]

- passive transport

- The movement of a solute across a membrane by traveling down an electrochemical or concentration gradient, using only the energy stored in the gradient and not any energy from external sources.[3] Contrast active transport.

- Pasteur effect

- A phenomenon observed in facultatively anaerobic cells, including animal tissues and many microorganisms such as yeast, whereby the presence of oxygen in the environment inhibits the cell's use of ethanol fermentation pathways to generate energy, and drives the cell to instead make use of the available oxygen in aerobic respiration;[20] or more generally the observed decrease in the rate of glycolysis or of lactate production in cells exposed to oxygenated air.[14]

- PCR

- See polymerase chain reaction.

- PCR product

- See amplicon.

- pentose

- Any simple sugar or monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms. The compounds ribose and deoxyribose are both pentose sugars, which, in the form of cyclic five-membered rings, serve as the central structural components of the ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleotides that make up RNA and DNA, respectively.

- peptidase

- See protease.

- peptide

- A short chain of amino acid monomers linked by covalent peptide bonds. Peptides are the fundamental building blocks of longer polypeptide chains and hence of proteins.

- peptide bond

- A covalent chemical bond between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of an adjacent amino acid in a peptide chain, formed by a dehydration reaction catalyzed by peptidyl transferase, an enzyme within the ribosome, during translation.

- pericentriolar material (PCM)

- perinuclear space

- The space between the inner and outer membranes of the nuclear envelope.

- peripheral membrane protein

- Any of a class of membrane proteins which attach only temporarily to the cell membrane, either by penetrating the lipid bilayer or by attaching to other proteins which are permanently embedded within the membrane.[21] The ability to reversibly interact with membranes makes peripheral membrane proteins important in many different roles, commonly as regulatory subunits of channel proteins and cell surface receptors. Their domains often undergo rearrangement, dissociation, or conformational changes when they interact with the membrane, resulting in the activation of their biological activity.[22] In protein purification, peripheral membrane proteins are typically more water-soluble and much easier to isolate from the membrane than integral membrane proteins.

- periplasmic space

- In a bacterial cell, the space between the cell membrane and the cell wall.[14]

- peroxisome

- A small membrane-bound organelle found in many eukaryotic cells which specializes in carrying out oxidative reactions with various enzyme peroxidases and catalase, generally to mitigate damage from reactive oxygen species but also as a participant in various metabolic pathways such as beta-oxidation of fatty acids.[23]

- persistence

- 1. The tendency of a moving cell to continue moving in the same direction as previously; that is, even in isotropic environments, there inevitably still exists an inherent bias by which, from instant to instant, cells are more likely not to change direction than to change direction. Averaged over long periods of time, however, this bias is less obvious and cell movements are better described as a random walk.[3]

- 2. The ability of some viruses to remain present and viable in cells, organisms, or populations for very long periods of time by any of a variety of strategies, including retroviral integration and immune suppression, often in a latent form which replicates very slowly or not at all.[3]

- pervasive transcription

- Petri dish

- A shallow, transparent plastic or glass dish, usually circular and covered with a lid, which is widely used in biology laboratories to hold solid or liquid growth media for the purpose of culturing cells. They are particularly useful for adherent cultures, where they provide a flat, sterile surface conducive to colony formation from which scientists can easily isolate and identify individual colonies.

- phagocyte

- A type of cell which functions as part of the immune system by engulfing and ingesting harmful foreign molecules, bacteria, and dead or dying cells in a process known as phagocytosis.

- phagocytosis

- The process by which foreign cells, molecules, and small particulate matter are engulfed and ingested via endocytosis by specialized cells known as phagocytes (a class which includes macrophages and neutrophils).[4]

- phagosome

- A large, intracellular, membrane-bound vesicle formed as a result of phagocytosis and containing whatever previously extracellular material was engulfed during that process.[4]

- pharmacogenomics

- The study of the role played by the genome in the body's response to pharmaceutical drugs, combining the fields of pharmacology and genomics.

- phenome

- The complete set of phenotypes that are or can be expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, organism, or species; the sum of all of its manifest chemical, morphological, and behavioral characteristics or traits.

- phenomic lag

- A delay in the phenotypic expression of a genetic mutation owing to the time required for the manifestation of changes in the affected biochemical pathways.[8]

- phenotype

- The composite of the observable morphological, physiological, and behavioral traits of an organism that result from the expression of the organism's genotype as well as the influence of environmental factors and the interactions between the two.

- phenotypic switching

- A type of phenotypic plasticity in which a cell rapidly undergoes major changes to its morphology and/or function, usually via epigenetic modifications, allowing it to quickly switch back and forth between disparate phenotypes in response to changes in the local microenvironment.

- phosphatase

- Any of a class of enzymes that catalyze the hydrolytic cleavage of a phosphoric acid monoester into a phosphate ion and an alcohol, e.g. the removal of a phosphate group from a nucleotide via the breaking of the ester bond connecting the phosphate to a ribose or deoxyribose sugar or to another phosphate, a process termed dephosphorylation. The opposite process is performed by kinases.

- phosphate

- Any chemical species or functional group derived from phosphoric acid (H

3PO

4) by the removal of one or more protons (H+

); the completely ionized form, [PO

4]3−

, consists of a single, central phosphorus atom covalently bonded to four oxygen atoms via three single bonds and one double bond. Phosphates are abundant and ubiquitous in biological systems, where they occur either as free anions in solution, known as inorganic phosphates and symbolized Pi, or bonded to organic molecules via ester bonds. The huge diversity of organophosphate compounds includes all nucleotides, the structural backbone of long nucleotide chains such as DNA and RNA, created when the phosphate groups of nucleotides form phosphodiester bonds with each other, as well as ADP and ATP, whose high-energy diphosphate and triphosphate substituents are essential energy carriers in all cells. Enzymes known as kinases and phosphatases catalyze the addition and removal of phosphate groups to and from these and other biomolecules. - phosphate backbone

- The linear chain of alternating phosphate and sugar compounds that results from the linking of consecutive nucleotides in the same strand of a nucleic acid molecule, and which serves as the structural framework of the nucleic acid. Each individual strand is held together by a repeating series of phosphodiester bonds connecting each phosphate group to the ribose or deoxyribose sugars of two adjacent nucleotides. These bonds are created by ligases and broken by nucleases.

- phosphodiester bond

- A pair of ester bonds linking a phosphate molecule with the two pentose rings of consecutive nucleosides on the same strand of a nucleic acid. Each phosphate forms a covalent bond with the 3' carbon of one pentose and the 5' carbon of the adjacent pentose; the repeated series of such bonds that holds together the long chain of nucleotides comprising DNA and RNA molecules is known as the phosphate or phosphodiester backbone.

- phospholipid

- Any of a subclass of lipids consisting of a central alcohol (usually glycerol) covalently bonded to three functional groups: a negatively charged phosphate group, and two long fatty acid chains. This arrangement results in a highly amphipathic molecule which in aqueous solutions tends to aggregate with other, similar molecules in a lamellar or micellar conformation with the hydrophilic phosphate "heads" oriented outward, exposing them to the solution, and the hydrophobic fatty acid "tails" oriented inward, minimizing their interactions with water and other polar compounds. Phospholipids are the major structural membrane lipid in almost all biological membranes except the membranes of some plant cells and chloroplasts, where glycolipids dominate instead.[3]

- phospholipid bilayer

- See lipid bilayer.

- phosphorylation

- The attachment of a phosphate ion, PO3−

4, to another molecule or ion or to a protein by covalent bonding. Phosphorylation and the inverse reaction, dephosphorylation, are essential steps in numerous biochemical pathways, including in the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (as in oxidative phosphorylation); in the metabolism of glucose and the synthesis of glycogen; and in the post-translational modification of amino acid residues in many proteins. Enzymes which catalyze phosphorylation reactions are known as kinases; those that catalyze dephosphorylation are known as phosphatases. - piRNA

- See Piwi-interacting RNA.

- pitch

- The number of base pairs contained within a single complete turn of the DNA double helix,[12] used as a measure of the "tightness" or density of the helix's spiral.

- Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA)

- plasma membrane

- See cell membrane.

- plasmid

- Any small DNA molecule that is physically separated from the larger body of chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. Plasmids are typically small (less than 100 kbp), circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in prokaryotes such as bacteria, though they are also sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotes.

- plasmid partitioning

- The process by which plasmids which have been replicated inside a parent cell are distributed equally between daughter cells during cell division.[3]

- plasmid-mediated resistance

- The development of resistance to toxins or antibiotics which is enabled by the horizontal transfer of resistance genes encoded within small, independently replicating DNA molecules known as plasmids. This process occurs naturally via mechanisms such as bacterial conjugation, but is also a common aspect of genetic engineering methods such as molecular cloning.

- plastid

- Any of a class of membrane-bound organelles found in the cells of some eukaryotes such as plants and algae which are hypothesized to have evolved from endosymbiotic cyanobacteria; examples include chloroplasts, chromoplasts, and leucoplasts. Plastids retain their own circular chromosomes which replicate independently of the host cell's genome. Many contain photosynthetic pigments which allow them to perform photosynthesis, while others have been retained for their ability to synthesize unique chemical compounds.

- pleomorphism

- 1. Variability in the size, shape, or staining of cells and/or their nuclei, particularly as observed in histology and cytopathology, where morphological variation is frequently an indicator of a cellular abnormality such as disease or tumor formation.

- 2. In microbiology, the ability of some microorganisms such as certain bacteria and viruses to alter their morphology, metabolism, or mode of reproduction in response to changes in their environment.

- plithotaxis

- The tendency of cells within a monolayer to migrate in the direction of the local highest tension or maximal principal stress, exerting minimal shear stress on neighboring cells and thereby propagating the tension across many intercellular junctions and causing the cells to exhibit a sort of collective migration.[24]

- ploidy

- The number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles present within the cell at any given autosomal locus.

- pluripotency

- plus-strand

- See coding strand.

- point mutation

- A mutation by which a single nucleotide base is changed, inserted, or deleted from a sequence of DNA or RNA.

- poly(A) tail

- polyadenylation

- The addition of a series of multiple adenosine ribonucleotides, known as a poly(A) tail, to the 3'-end of a primary RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA. A class of post-transcriptional modification, polyadenylation serves different purposes in different cell types and organisms. In eukaryotes, the addition of a poly(A) tail is an important step in the processing of a raw transcript into a mature mRNA, ready for export to the cytoplasm where translation occurs; in many bacteria, polyadenylation has the opposite function, instead promoting the RNA's degradation.

- polyclonal

- Describing cells, proteins, or molecules descended or derived from more than one clone (i.e. from more than one genome or genetic lineage) or made in response to more than one unique stimulus. Antibodies are often described as polyclonal if they have been produced or raised against multiple distinct antigens or multiple variants of the same antigen, such that they can recognize more than one unique epitope.[2] Contrast monoclonal.

- polylinker

- See multiple cloning site.

- polymer

- A macromolecule composed of multiple repeating subunits or monomers; a chain or aggregation of many individual molecules of the same compound or class of compound.[2] The formation of polymers is known as polymerization and generally only occurs when nucleation sites are present and the concentration of monomers is sufficiently high.[3] Many of the major classes of biomolecules are polymers, including nucleic acids and polypeptides.

- polymerase

- Any of a class of enzymes which catalyze the synthesis of polymeric molecules, especially nucleic acid polymers, typically by encouraging the pairing of free nucleotides to those of an existing complementary template. DNA polymerases and RNA polymerases are essential for DNA replication and transcription, respectively.

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Any of a wide variety of molecular biology methods involving the rapid production of millions or billions of copies of a specific DNA sequence, allowing scientists to selectively amplify fragments of a very small sample to a quantity large enough to study in detail. In its simplest form, PCR generally involves the incubation of a target DNA sample of known or unknown sequence with a reaction mixture consisting of oligonucleotide primers, a heat-stable DNA polymerase, and free deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), all of which are supplied in excess. This mixture is then alternately heated and cooled to pre-determined temperatures for pre-determined lengths of time according to a specified pattern which is repeated for many cycles, typically in a thermal cycler which automatically controls the required temperature variations. In each cycle, the most basic of which includes a denaturation phase, annealing phase, and elongation phase, the copies synthesized in the previous cycle are used as templates for synthesis in the next cycle, causing a chain reaction that results in the exponential growth of the total number of copies in the reaction mixture. Amplification by PCR has become a standard technique in virtually all molecular biology laboratories.

- polymerization

- The formation of a polymer from its constituent monomers; the chemical reaction or series of reactions by which monomeric subunits are covalently linked together into a polymeric chain or branching aggregate; e.g. the polymerization of a nucleic acid chain by linking consecutive nucleotides, a reaction catalyzed by a polymerase enzyme.

- polymorphism

- polypeptide

- A long, continuous, and unbranched polymeric chain of amino acid monomers linked by covalent peptide bonds, typically longer than a peptide. Proteins generally consist of one or more polypeptides folded or arranged in a biologically functional way.

- polyploid

- (of a cell or organism) Having more than two homologous copies of each chromosome; i.e. any ploidy level that is greater than diploid. Polyploidy may occur as a normal condition of chromosomes in certain cells or even entire organisms, or it may result from errors in cell division or mutations causing the duplication of the entire chromosome set.

- polysaccharide

- A linear or branched polymeric chain of carbohydrate monomers (monosaccharides). Examples include glycogen and cellulose.[4]

- polysome

- A complex of a messenger RNA molecule and two or more ribosomes which act to translate the mRNA transcript into a polypeptide.

- polysomy

- The condition of a cell or organism having at least one more copy of a particular chromosome than is normal for its ploidy level, e.g. a diploid organism with three copies of a given chromosome is said to show trisomy. Every polysomy is a type of aneuploidy.

- polytene chromosome

- position effect

- Any effect on the expression or functionality of a gene or sequence that is a consequence of its location or position within a chromosome or other DNA molecule. A sequence's precise location relative to other sequences and structures tends to strongly influence its activity and other properties, because different loci on the same molecule can have substantially different genetic backgrounds and physical/chemical environments, which may also change over time. For example, the transcription of a gene located very close to a nucleosome, centromere, or telomere is often repressed or entirely prevented because the proteins that make up these structures block access to the DNA by transcription factors, while the same gene is transcribed at a much higher rate when located in euchromatin. Proximity to promoters, enhancers, and other regulatory elements, as well as to regions of frequent transposition by mobile elements, can also directly affect expression; being located near the end of a chromosomal arm or to common crossover points may affect when replication occurs and the likelihood of recombination. Position effects are a major focus of research in the field of epigenetic inheritance.

- positional cloning

- A strategy for identifying and cloning a candidate gene based on knowledge of its locus or position alone and with little or no information about its products or function, in contrast to functional cloning. This method usually begins by comparing the genomes of individuals expressing a phenotype of unknown provenance (often a hereditary disease) and identifying genetic markers shared between them. Regions defined by markers flanking one or more genes of interest are cloned, and the genes located between the markers can then be identified by any of a variety of means, e.g. by sequencing the region and looking for open reading frames, by comparing the sequence and expression patterns of the region in mutant and wild-type individuals, or by testing the ability of the putative gene to rescue a mutant phenotype.[12]

- positive (+) sense strand

- See coding strand.

- positive control

- The initiation, activation, or enhancement of some biological process by the presence of a specific molecular entity (e.g. an activator or inducer), in the absence of which the process cannot proceed or is otherwise diminished.[14] In gene regulation, for example, the binding of an activating molecule such as a transcription factor to a promoter may recruit RNA polymerase to a coding sequence, thereby causing it to be transcribed. Contrast negative control.

- positive supercoiling

- The supercoiling of a double-stranded DNA molecule in the same direction as the turn of the double helix itself (e.g. a right-handed coiling of a helix with a right-handed turn).[8] Contrast negative supercoiling.

- post-transcriptional modification

- post-translational modification

- potency

- precursor cell

- A partially differentiated or intermediate stem cell with the ability to further differentiate into only one cell type; i.e. a unipotent stem cell that is the immediate parent cell from which fully differentiated cell types divide. The term "precursor cell" is sometimes used interchangeably with progenitor cell, though this term may also be considered technically distinct.

- Pribnow box

- primary transcript