Gospel of Luke

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

The Gospel of Luke[a] is the third of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus.[5] Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts,[6] accounting for 27.5% of the New Testament.[7] The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the messiah (Christ) from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.[citation needed]

Most modern scholars agree that the main sources used for Luke were (1) the Gospel of Mark; (2) a hypothetical collection of sayings, called the Q source; and (3) material found in no other gospels, often called the L (for Luke) source, though alternative hypotheses that posit the direct use of Matthew by Luke or vice versa without Q are increasing in popularity within scholarship.[8][9][10] If and to what extent the author made own amendments is unclear. The author is anonymous;[11] perhaps most scholars think that he was a companion of Paul, but others cite differences between him and the Pauline epistles.[12][13][14] The most common dating for its composition is around AD 80–90 and there is evidence that it was still being revised well into the 2nd century.[15][16]

Composition

[edit]Textual history

[edit]

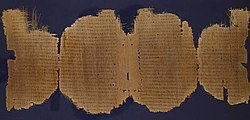

Autographs (original copies) of Luke and the other Gospels have not been preserved; the texts that survive are third-generation copies, with no two completely identical.[17] The earliest witnesses (the technical term for written manuscripts) for the Gospel of Luke fall into two "families" with considerable differences between them, the Western and the Alexandrian text-type, and the dominant view is that the Western text represents a process of deliberate revision, as the variations seem to form specific patterns.[18]

The fragment 𝔓4 is often cited as the oldest witness. It has been dated from the late 2nd century, although this dating is disputed. Papyrus 75 (= Papyrus Bodmer XIV–XV) is another very early manuscript (late 2nd/early 3rd century), and it includes an attribution of the Gospel to Luke. The oldest complete texts are the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, both from the Alexandrian family; Codex Bezae, a 5th- or 6th-century Western text-type manuscript that contains Luke in Greek and Latin versions on facing pages, appears to have descended from an offshoot of the main manuscript tradition, departing from more familiar readings at many points. Codex Bezae shows comprehensively the differences between the versions which show no core theological significance.[19][b]

Luke–Acts: unity, authorship and date

[edit]The gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles make up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts.[6] Together they account for 27.5% of the New Testament, the largest contribution by a single author, providing the framework for both the Church's liturgical calendar and the historical outline into which later generations have fitted their idea of the story of Jesus.[7]

The author is not named in either volume,[11] but he was educated, a man of means, probably urban, and someone who respected manual work, although not a worker himself; this is significant, because more highbrow writers of the time looked down on the artisans and small business-people who made up the early church of Paul and who were presumably Luke's audience.[20] According to a Church tradition first recorded by Irenaeus (c. AD 130 – c. AD 202) he was the Luke named as a companion of Paul in three of the Pauline letters, but "a critical consensus emphasizes the countless contradictions between the account in Acts and the authentic Pauline letters":[12] an example can be seen by comparing Acts' accounts of Paul's conversion (Acts 9:1–31,[21] Acts 22:6–21,[22] and Acts 26:9–23)[23] with Paul's own statement that he remained unknown to Christians in Judea after that event in Galatians 1:17–24,[24][25]), and while the author of the Gospel of Luke clearly admired Paul, his theology differs significantly from Paul's on key points and he does not represent Paul's views accurately.[26] Many modern scholars have therefore expressed doubt that the author of Luke-Acts was the physician Luke, and critical opinion on the subject was assessed to be roughly evenly divided near the end of the 20th century.[27] Most scholars maintain that the author of Luke-Acts, whether named Luke or not, met Paul.[28]

The interpretation of the "we" passages in Acts as indicative that the writer relied on a historical eyewitness (whether Luke the evangelist or not), remains the most influential in current biblical studies.[29] Objections to this viewpoint, among others, include the claim that Luke-Acts contains differences in theology and historical narrative which are irreconcilable with the authentic letters of Paul the Apostle.[30]

The eclipse of the traditional attribution to Luke the companion of Paul has meant that an early date for the gospel is now rarely put forward.[12] Most scholars date the composition of the combined work to around AD 80–90, and there is textual evidence (the conflicts between Western and Alexandrian manuscript families) that Luke–Acts was still being substantially revised well into the 2nd century.[16][31]

Genre, models and sources

[edit]Luke–Acts is a religio-political history of the founder of the church and his successors, in both deeds and words. The author describes his book as a "narrative" (diegesis), rather than as a gospel, and implicitly criticises his predecessors for not giving their readers the speeches of Jesus and the Apostles, as such speeches were the mark of a "full" report, the vehicle through which ancient historians conveyed the meaning of their narratives. He seems to have taken as his model the works of two respected Classical authors, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who wrote a history of Rome (Roman Antiquities), and the Jewish historian Josephus, author of a history of the Jews (Antiquities of the Jews). All three authors anchor the histories of their respective peoples by dating the births of the founders (Romulus, Moses, and Jesus) and narrate the stories of the founders' births from God, so that they are sons of God. Each founder taught authoritatively, appeared to witnesses after death, and ascended to heaven. Crucial aspects of the teaching of all three concerned the relationship between rich and poor and the question of whether "foreigners" were to be received into the people.[32]

Mark, written around AD 70, provided the narrative outline for Luke, but Mark contains comparatively little of Jesus' teachings,[33] and for these most scholars believe Luke likely turned to a hypothesized collection of sayings called Q source, which would have consisted mostly, although not exclusively, of "sayings".[34][8] A growing number of scholars support alternative hypotheses, such as the Farrer Hypothesis and the Matthean Posteriority Hypothesis, which argue for Luke's direct usage of Matthew and Matthew's dependence on Luke, respectively, and dispense with Q.[9][35] Mark and Q account for about 64% of Luke; the remaining material, known as the L source, is of unknown origin and date.[36] Most Q and L-source material is grouped in two clusters, Luke 6:17–8:3 and 9:51–18:14, and L-source material forms the first two sections of the gospel (the preface and infancy and childhood narratives).[37] If and to what extent the author of Luke made his own amendments is unclear.

Audience and authorial intent

[edit]The Gospel of Luke is unique among the canonical gospels for declaring the purpose and method of his work in a prologue, trying to render the Christian message in a higher literary plane. The author both classifies himself as among the many who previously attempted to write narratives of Christ while claiming his work is better and more reliable. Luke's claims of careful investigation, orderly writing, and access to accounts handed down to his community by eyewitnesses[38] is intended to demonstrate his gospel's superiority to its predecessors.[39][40] Luke was written to be read aloud to a group of Jesus-followers gathered in a house to share the Lord's Supper.[32] The author assumes an educated Greek-speaking audience, but directs his attention to specifically Christian concerns rather than to the Greco-Roman world at large.[41] He begins his gospel with a preface addressed to "Theophilus":[42] the name means "Lover of God", and could refer to any Christian, though most interpreters consider it a reference to a Christian convert and Luke's literary patron.[43] Here he informs Theophilus of his intention, which is to lead his reader to certainty through an orderly account "of the events that have been fulfilled among us."[20] He did not, however, intend to provide Theophilus with a historical justification of the Christian faith – "did it happen?" – but to encourage faith – "what happened, and what does it all mean?"[44]

Structure and content

[edit]Structure

[edit]Following the author's preface addressed to his patron and the two birth narratives (John the Baptist and Jesus), the gospel opens in Galilee and moves gradually to its climax in Jerusalem:[45]

- A brief preface addressed to Theophilus stating the author's aims;

- Birth and infancy narratives for both Jesus and John the Baptist, interpreted as the dawn of the promised era of Israel's salvation;

- Preparation for Jesus' messianic mission: John's prophetic mission, his baptism of Jesus, and the testing of Jesus' vocation;

- The beginning of Jesus' mission in Galilee, and the hostile reception there;

- The central section: the journey to Jerusalem, where Jesus knows he must meet his destiny as God's prophet and Messiah;

- His mission in Jerusalem, culminating in confrontation with the leaders of the Jewish Temple;

- His last supper with his most intimate followers, followed by his arrest, interrogation, and crucifixion;

- God's validation of Jesus as Christ: events from the first Easter to the Ascension, showing Jesus' death to be divinely ordained, in keeping with both scriptural promise and the nature of messiahship, and anticipating the story of Acts.[c]

Parallel structure of Luke–Acts

[edit]The structure of Acts parallels the structure of the gospel, demonstrating the universality of the divine plan and the shift of authority from Jerusalem to Rome:[46]

- The gospel – the acts of Jesus:

- The presentation of the child Jesus at the Temple in Jerusalem

- Jesus' forty days in the desert

- Jesus in Samaria/Judea

- Jesus in the Decapolis

- Jesus receives the Holy Spirit

- Jesus preaches with power (the power of the spirit)

- Jesus heals the sick

- Death of Jesus

- The apostles are sent to preach to all nations

- The acts of the apostles:

- Jerusalem

- Forty days before the Ascension

- Samaria

- Asia Minor

- Pentecost: Christ's followers receive the spirit

- The apostles preach with the power of the spirit

- The apostles heal the sick

- Death of Stephen, the first martyr for Christ

- Paul preaches in Rome

Theology

[edit]

Luke's "salvation history"

[edit]Luke's theology is expressed primarily through his overarching plot, the way scenes, themes and characters combine to construct his specific worldview.[47] His "salvation history" stretches from the Creation to the present time of his readers, in three ages: first, the time of "the Law and the Prophets", the period beginning with Genesis and ending with the appearance of John the Baptist;[48] second, the epoch of Jesus, in which the Kingdom of God was preached;[49] and finally the period of the Church, which began when the risen Christ was taken into Heaven, and would end with his second coming.[50]

Christology

[edit]Luke's understanding of Jesus – his Christology – is central to his theology. One approach to this is through the titles Luke gives to Jesus: these include, but are not limited to, Christ (Messiah), Lord, Son of God, and Son of Man.[51] Another is by reading Luke in the context of similar Greco-Roman divine saviour figures (Roman emperors are an example), references which would have made clear to Luke's readers that Jesus was the greatest of all saviours.[52] A third is to approach Luke through his use of the Old Testament, those passages from Jewish scripture which he cites to establish that Jesus is the promised Messiah.[53] While much of this is familiar, much also is missing: for example, Luke makes no clear reference to Christ's pre-existence or to the Christian's union with Christ, and makes relatively little reference to the concept of atonement: perhaps he felt no need to mention these ideas, or disagreed with them, or possibly he was simply unaware of them.[54]

Even what Luke does say about Christ is ambiguous or even contradictory.[54] For example, according to Luke 2:11 Jesus was the Christ at his birth, but in Acts 2:36 he becomes Christ at the resurrection, while in Acts 3:20 it seems his messiahship is active only at the parousia, the "second coming"; similarly, in Luke 2:11 he is the Saviour from birth, but in Acts 5:31[55] he is made Saviour at the resurrection; and he is born the Son of God in Luke 1:32–35,[56] but becomes the Son of God at the resurrection according to Acts 13:33.[57][58] Many of these differences may be due to scribal error, but others are argued to be deliberate alterations to doctrinally unacceptable passages, or the introduction by scribes of "proofs" for their favourite theological tenets.[59]

The Holy Spirit, the Christian community, and the Kingdom of God

[edit]The Holy Spirit plays a more important role in Luke–Acts than in the other gospels. Some scholars have argued that the Spirit's involvement in the career of Jesus is paradigmatic of the universal Christian experience, others that Luke's intention was to stress Jesus' uniqueness as the Prophet of the final age.[60] It is clear, however, that Luke understands the enabling power of the Spirit, expressed through non-discriminatory fellowship ("All who believed were together and had all things in common"), to be the basis of the Christian community.[61] This community can also be understood as the Kingdom of God, although the kingdom's final consummation will not be seen till the Son of Man comes "on a cloud" at the end-time.[62]

Christians vs. Rome and the Jews

[edit]Luke needed to define the position of Christians in relation to two political and social entities, the Roman Empire and Judaism. Regarding the Empire, Luke makes clear that, while Christians are not a threat to the established order, the rulers of this world hold their power from Satan, and the essential loyalty of Christ's followers is to God and this world will be the kingdom of God, ruled by Christ the King.[63] Regarding the Jews, Luke emphasises the fact that Jesus and all his earliest followers were Jews, although by his time the majority of Christ-followers were gentiles; nevertheless, the Jews had rejected and killed the Messiah, and the Christian mission now lay with the gentiles.[64]

Comparison with other writings

[edit]

Synoptics

[edit]The gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke share so much in common that they are called the Synoptics, as they frequently cover the same events in similar and sometimes identical language. The majority opinion among scholars is that Mark was the earliest of the three (about AD 70) and that Matthew and Luke both used this work and the "sayings gospel" known as Q as their basic sources, though a growing number support alternative hypotheses, such as the Farrer Hypothesis and the Matthean Posteriority Hypothesis, which argue for Luke's direct usage of Matthew and Matthew's dependence on Luke, respectively, and dispense with Q.[9][65] Luke has both expanded Mark and refined his grammar and syntax, as Mark's Greek writing is less elegant. Some passages from Mark he has eliminated, notably most of chapters 6 and 7, which he apparently felt reflected poorly on the disciples and painted Jesus too much like a magician. The disciple Peter is given a notably more positive depiction than the other three gospels, with his failings either occluded or excused, and his merits and role emphasized.[66] Despite this, he follows Mark's narrative more faithfully than does Matthew.[67]

The Gospel of John

[edit]Despite being grouped with Matthew and Mark, the Gospel of Luke has a number of parallels with the Gospel of John which are not shared by the other synoptics:

- Luke uses the terms "Jews" and "Israelites" in a way unlike Mark, but like John.

- Both gospels have characters named Mary of Bethany, Martha, and Lazarus, although John's Lazarus is portrayed as a real person, while Luke's is a figure in a parable.

- There are several points where Luke's passion narrative resembles that of John.[68][69] At Jesus' arrest, only Luke and John state that the servant's right ear was cut off.[70][71]

There are also several other parallels that scholars have identified.[72] Recently, some scholars have proposed that the author of John's gospel may have specifically redacted and responded to the Gospel of Luke.[73]

The Gospel of Marcion

[edit]Some time in the 2nd century, the Christian thinker Marcion of Sinope began using a gospel that was very similar to, but shorter than, canonical Luke. Marcion was well known for preaching that the god who sent Jesus into the world was a different, higher deity than the creator god of Judaism.[74] The majority of scholars view the Gospel of Marcion as a later work that edited the gospel of Luke.[75][76]

While no manuscript copies of Marcion's gospel survive, reconstructions of his text have been published by Adolf von Harnack and Dieter T. Roth,[77] based on quotations in the anti-Marcionite treatises of orthodox Christian apologists, such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Epiphanius. These early apologists accused Marcion of having "mutilated" canonical Luke by removing material that contradicted his unorthodox theological views.[78] According to Tertullian, Marcion also accused his orthodox opponents of having "falsified" canonical Luke.[79]

Like the Gospel of Mark, Marcion's gospel lacked any nativity story, and Luke's account of the baptism of Jesus was absent. The Gospel of Marcion also omitted Luke's parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son.[80]

See also

[edit]- Authorship of Luke–Acts

- List of Gospels

- List of omitted Bible verses

- Marcion

- Order of St. Luke

- Synoptic Gospels

- Synoptic problem

- Textual variants in the Gospel of Luke

Notes

[edit]- ^ The book is sometimes called the Gospel according to Luke (Ancient Greek: Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Λουκᾶν, romanized: Euangélion katà Loukân[2]), or simply Luke[3] (which is also its most common form of abbreviation).[4]

- ^ Verses 22:19–20 are omitted in Codex Bezae and a handful of Old Latin manuscripts. Nearly all other manuscripts including Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus and Church Fathers contain the "longer" reading of Luke 22:19 and 20. Verse 22:20, which is very similar to 1 Corinthians 11:25, and provides gospel support for the doctrine of the New Covenant, along with Matthew 26:28 and Mark 14:24 (both, in the Textus Receptus Greek manuscript). Verses 22:43–44

- ^ For studies of the literary structure of this Gospel, see recent contributions of Bailey, Goulder and Talbert, in particular for their readings of Luke's Central Section. (Almost all scholars believe the section begins at 9.51; strong case, however, can be put for 9.43b.) Then the introductory pieces to the opening and closing parts that frame the teaching of the Central Section would exhibit a significant dualism: compare 9.43b–45 and 18.31–35. The Central Section would then be defined as 9.43b–19.48, 'Jesus Journey to Jerusalem and its Temple'. Between the opening part ('His Setting out', 9.43b–10.24) and the closing part ('His Arriving', 18.31–19.48) lies a chiasm of parts 1–5,C,5'–1', 'His Teachings on the Way': 1, 10.25–42 Inheriting eternal life: law and love; 2, 11.1–13 Prayer: right praying, persistence, Holy Spirit is given; 3, 11.14–12.12 The Kingdom of God: what is internal is important; 4, 12.13–48 Earthly and Heavenly riches; the coming of the Son of Man; 5, 12.49–13.9 Divisions, warning and prudence, repentance; C, 13.10–14.24 a Sabbath healing, kingdom and entry (13.10–30), Jesus is to die in Jerusalem, his lament for it (13.31–35), a Sabbath healing, banqueting in the kingdom (14.1–24); 5', 14.25–15.32 Divisions, warning and prudence, repentance; 4', 16.1–31 Earthly and Heavenly riches: the coming judgement; 3', 17.1–37 The kingdom of God is 'within', not coming with signs; 2', 18.1–17 Prayer: persistence, right praying, receiving the kingdom; 1', 18.18–30 Inheriting eternal life: law and love. (All the parts 1–5 and 5'–1' are constructed of three parts in the style of ABB'.)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023.

- ^ Gathercole 2013, pp. 66–71.

- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 855. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Bible Book Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Allen 2009, p. 325.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 195.

- ^ a b Boring 2012, p. 556.

- ^ a b Duling 2010, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Runesson, Anders (2021). Jesus, New Testament, Christian Origins. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802868923.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem 2022: Proceedings of the Loyola University Conference. Peeters Pub and Booksellers. 2023. ISBN 9789042950344.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Ehrman 2005, pp. 172, 235.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2015). Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Volume 1). Baker Academic. p. 402. ISBN 978-0801039898.

- ^ Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-2475-6.

- ^ a b Perkins 2009, pp. 250–53.

- ^ Ehrman 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 596.

- ^ Ellis 2003, p. 19.

- ^ a b Green 1997, p. 35.

- ^ Acts 9:1–31

- ^ Acts 22:6–21

- ^ Acts 26:9–23

- ^ Galatians 1:17–24

- ^ Perkins 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 590.

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. (1997). Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. pp. 267–8. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2015). Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Volume 1). Baker Academic. p. 402. ISBN 978-0801039898.

- ^ "A glance at recent extended treatments of the "we" passages and commentaries demonstrates that, within biblical scholarship, solutions in the historical eyewitness traditions continue to be the most influential explanations for the first-person plural style in Acts. Of the two latest full-length studies on the "we" passages, for example, one argues that the first-person accounts came from Silas, a companion of Paul but not the author, and the other proposes that first-person narration was Luke's (Paul's companion and the author of Acts) method of communicating his participation in the events narrated.17 17. Jurgen Wehnert, Die Wir-Passegen der Apostelgeschitchte: Ein lukanisches Stilmittel aus judischer Tradition (GTA 40; Gottingen: Vanderhoeck & Ruprecht, 1989); Claus-Jurgen Thornton, Der Zeuge des Zeugen: Lukas als Historiker der Paulus reisen (WUNT 56; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1991). See also, Barrett, Acts of the Apostles, and Fitzmyer, Acts of the Apostles.", Campbell, "The "we" passages in the Acts of the Apostles: the narrator as narrative", p. 8 (2007). Society of Biblical Literature.

- ^ "The principle essay in this regard is P. Vielhauer, 'On the "Paulinism" of Acts', in L.E. Keck and J. L. Martyn (eds.), Studies in Luke-Acts (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), 33-50, who suggests that Luke's presentation of Paul was, on several fronts, a contradiction of Paul's own letters (e.g. attitudes on natural theology, Jewish law, christology, eschatology). This has become the standard position in German scholarship, e.g., Conzelmann, Acts; J. Roloff, Die Apostelgeschichte (NTD; Berlin: Evangelische, 1981) 2-5; Schille, Apostelgeschichte des Lukas, 48-52. This position has been challenged most recently by Porter, "The Paul of Acts and the Paul of the Letters: Some Common Misconceptions', in his Paul of Acts, 187-206. See also I.H. Marshall, The Acts of the Apostles (TNTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; Leister: InterVarsity Press, 1980) 42-44; E.E. Ellis, The Gospel of Luke (NCB; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; London: Marshall, Morgan and Scott, 2nd edn, 1974) 45-47.", Pearson, "Corresponding sense: Paul, dialectic, and Gadamer", Biblical Interpretation Series, p. 101 (2001). Brill.

- ^ Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-2475-6.

- ^ a b Balch 2003, p. 1104.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 284.

- ^ Ehrman 1999, p. 82.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem 2022: Proceedings of the Loyola University Conference. Peeters Pub and Booksellers. 2023. ISBN 9789042950344.

- ^ Powell 1998, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 204.

- ^ Green 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Bovon, Francois (2002). Luke 1: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 1:1-9:50. Fortress Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780800660444.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2020). The Gospel as Manuscript: An Early History of the Jesus Tradition as Material Artifact. Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0199384372.

- ^ Green 1995, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Luke 1:3; cf. Acts 1:1

- ^ Maier 2013, p. 417.

- ^ Green 1997, p. 36.

- ^ Carroll 2012, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 569.

- ^ Allen 2009, p. 326.

- ^ Luke 1:5–3:1

- ^ Luke 3:2–24:51

- ^ Evans 2011, p. no page numbers.

- ^ Powell 1989, p. 60.

- ^ Powell 1989, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Powell 1989, p. 66.

- ^ a b Buckwalter 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Acts 5:31

- ^ Luke 1:32–35

- ^ Acts 13:33

- ^ Ehrman 1996, p. 65.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Powell 1989, pp. 108–11.

- ^ Powell 1989, p. 111.

- ^ Holladay 2011, p. no page number.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 562.

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 563.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem 2022: Proceedings of the Loyola University Conference. Peeters Pub and Booksellers. 2023. ISBN 9789042950344.

- ^ Damgaard 2015, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Johnson 2010, p. 48.

- ^ Nicoll, W. R., Expositor's Greek Testament on Luke 22, accessed 30 October 2023

- ^ Jerusalem Bible (1966), footnote a at Luke 22

- ^ Luke 22:50

- ^ John 18:10

- ^ Boring 2012, p. 576.

- ^ MacDonald 2015.

- ^ BeDuhn 2015, p. 165.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2020). The Gospel as Manuscript. Oxford University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0199384372.

- ^ Bernier, Jonathan (2022). Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-3467-1.

According to late second- and early third-century fathers, Marcion (who was active in Rome in probably the 140s) produced a version of Luke's Gospel shorn of material that he found to be doctrinally unacceptable. For the most part, critical scholarship has been content to affirm these patristic reports.

- ^ Roth 2015.

- ^ BeDuhn 2015, p. 166.

- ^ BeDuhn 2015, p. 167-168, citing Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.4.

- ^ BeDuhn 2015, p. 170.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, O. Wesley Jr. (2009). "Luke". In Petersen, David L.; O'Day, Gail R. (eds.). Theological Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-1-61164-030-4.

- Balch, David L. (2003). "Luke". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- BeDuhn, Jason (2015). "The New Marcion" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 163–179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25592-3.

- Buckwalter, Douglas (1996). The Character and Purpose of Luke's Christology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56180-8.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Carroll, John T. (2012). Luke: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22106-5.

- Damgaard, Finn (2015). "Moving the People to Repentance: Peter in Luke-Acts". In Bond, Helen; Hurtado, Larry (eds.). Peter in Early Christianity. William B. Eerdmans. pp. 121–129. ISBN 978-0-8028-7171-8.

- Duling, Dennis C. (2010). "The Gospel of Matthew". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. Wiley–Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-1894-4.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1996). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510279-6.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983943-8.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- Ellis, E. Earle (2003). The Gospel of Luke. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-207-2.

- Evans, Craig A. (2011). Luke. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4412-3652-4.

- Gathercole, Simon J. (2013), "The Titles of the Gospels in the Earliest New Testament Manuscripts" (PDF), Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, 104 (1): 33–76, doi:10.1515/znw-2013-0002, S2CID 170079937, archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2014

- Green, Joel (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Luke. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46932-6.

- Green, Joel (1997). The Gospel of Luke. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2315-1.

- Holladay, Carl R. (2011). A Critical Introduction to the New Testament: Interpreting the Message and Meaning of Jesus Christ. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-4828-8.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3167-5.

- Johnson, Luke Timothy (2010). The New Testament: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974599-9.

- MacDonald, Dennis R. (2015). "John's Radical Rewriting of Luke-Acts" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 111–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Maier, Paul L. (2013). "Luke as a Hellenistic Historian". In Pitts, Andrew; Porter, Stanley (eds.). Christian Origins and Greco-Roman Culture. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-23416-1.

- Miller, Philip M. (2011). "The Least Orthodox Reading is to be Preferred". In Wallace, Daniel B. (ed.). Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-8906-8.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7.

- Perkins, Pheme (2009). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6553-3.

- Powell, Mark Allan (1989). What Are They Saying About Luke?. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3111-2.

- Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- Roth, Dieter T. (2015). The Text of Marcion's Gospel. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24520-4.

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998) [1996]. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Translated by Bowden, John. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-3123-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Adamczewski, Bartosz (2010). Q or not Q? The So-Called Triple, Double, and Single Traditions in the Synoptic Gospels. Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-631-60492-2.

- Aune, David E. (1988). The New Testament in its literary environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John, eds. (2007). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927718-6.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-2475-6.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2000). Cosmology and Eschatology in Jewish and Christian Apocalypticism. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11927-7.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Gamble, Harry Y. (1995). Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06918-1.

- Goodacre, Mark (2002). The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. Trinity Press International. ISBN 1-56338-334-9.

- Grobbelaar, Jan (2020). "Doing theology with children: A childist reading of the childhood metaphor in 1 Corinthians and the Synoptic Gospels". HTS Theological Studies. 76 (4): 1–9. doi:10.4102/hts.v76i4.5637. hdl:2263/76468. ISSN 0259-9422.

- Lössl, Josef (2010). The Early Church: History and Memory. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-16561-9.

- McReynolds, Kathy (1 May 2016). "The Gospel of Luke: A Framework for a Theology of Disability". Christian Education Journal. 13 (1): 169–178. doi:10.1177/073989131601300111. ISSN 0739-8913. S2CID 148901462.

- Metzger, James (22 February 2011). "Disability and the marginalisation of God in the Parable of the Snubbed Host (Luke 14.15-24)". The Bible and Critical Theory. 6 (2). ISSN 1832-3391. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Morris, Leon (1990). New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-45571-4.

- Smith, Dennis E. (1987). "Table Fellowship as a Literary Motif in the Gospel of Luke". Journal of Biblical Literature. 106 (4): 613–638. doi:10.2307/3260823. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3260823.

- Story, Lyle (2012). "One banquet with many courses" (PDF). Journal of Biblical and Pneumatological Research. 4: 67–93. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2021 – via EBSCO.

- Strecker, Georg (2000). Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-664-22336-6.

- Strelan, Rick (2013). Luke the Priest – the Authority of the Author of the Third Gospel. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-7788-4.

- Talbert, Charles H. (2002). Reading Luke: A Literary and Theological Commentary. Smyth & Helwys. ISBN 978-1-57312-393-8.

- Thompson, Richard P. (2010). "Luke–Acts: The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. Wiley–Blackwell. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-4443-1894-4.

- Twelftree, Graham H. (1999). Jesus the miracle worker: a historical & theological study. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1596-8.

- van Aarde, Andries (2019). "Syncrisis as literary motif in the story about the grown-up child Jesus in the temple (Luke 2:41-52 and the Thomas tradition)". HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies. 75 (3). doi:10.4102/HTS.V75I3.5258. hdl:2263/76046.

- VanderKam, James C.; Flint, Peter W. (2005). The meaning of the Dead Sea scrolls: Their significance for understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 0-567-08468-X.

External links

[edit]- Bible Gateway 35 languages/50 versions at GospelCom.net

- Unbound Bible 100+ languages/versions at Biola University

- Online Bible at gospelhall.org

- Early Christian Writings; Gospel of Luke: introductions and e-texts

- French; English translation

Bible: Luke public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: Luke public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions- A Brief Introduction to Luke–Acts is available online. Archived 14 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- B.H. Streeter, The Four Gospels: A study of origins 1924. Archived 6 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Willker, W (2007), A textual commentary on the Gospel of Luke, Pub. on-line A very detailed text-critical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 467 pages)

KSF

KSF