Great Wall of Sand

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

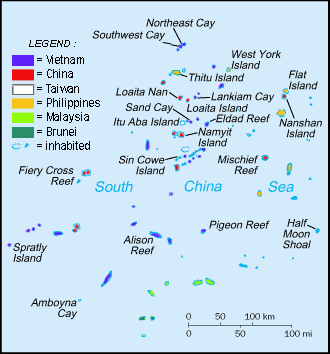

The "Great Wall of Sand" is a series of land reclamation (artificial island building) projects by the People's Republic of China (PRC) in the Spratly Islands area of the South China Sea between late 2013 to late 2016.[1]

2013–2016 Spratlys reclamations

[edit]In late 2013, the PRC embarked on very large scale reclamations at seven locations in order to strengthen territorial claims to the region demarcated by the nine-dash line.[2][3][4]

The artificial islands were created by dredging sand onto reefs which were then concreted to make permanent structures. By the time of the 2015 Shangri-La Dialogue, over 810 hectares (2,000 acres) of new land had been created.[5] By December 2016 it had reached 1,300 hectares (3,200 acres) and "'significant' weapons systems, including anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems" had been installed.[6] The name "Great Wall of Sand" was first[citation needed] used in March 2015 by U.S. Admiral Harry Harris, who was commander of the Pacific Fleet.[1]

The PRC states that the construction is for "improving the working and living conditions of people stationed on these islands",[7] and that, "China is aiming to provide shelter, aid in navigation, weather forecasts and fishery assistance to ships of various countries passing through the sea."[8]

Defence analysts IHS Jane's states that it is a "methodical, well planned campaign to create a chain of air and sea-capable fortresses".[9] These "military-ready" installations include sea-walls and deep-water ports, barracks and notably include runways on three of the reclaimed "islands", including Fiery Cross Reef,[10][11] Mischief Reef and Subi Reef.[2] Aside from geo-political tensions, concerns have been raised about the environmental impact on fragile reef ecosystems through the destruction of habitat, pollution and interruption of migration routes.[12]

The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative's "Island tracker" has listed the following locations as the sites of the PRC island reclamation activities:[13]

| Name | Reclaimed area | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Filipino | Vietnamese | Facilities added | acres | hectares | Ref. |

| Cuarteron Reef | Huáyáng Jiāo (华阳礁) | Calderon Reef | Đá Châu Viên | Access channel, breakwaters, multiple support buildings, new helipad, possible radar facility | 56 | 23 | [1] |

| Fiery Cross Reef | Yǒngshǔ Jiāo (永暑礁) | Kagitingan Reef | Đá Chữ Thập | Airstrip (~3000m), harbor, multiple cement plants, multiple support buildings, piers | 677 | 274 | [2] |

| Gaven Reefs | Nánxūn Jiāo (南薰礁) | Burgos Reefs | Đá Ga Ven | Access channel, anti-aircraft guns, communications equipment, construction support structure, defensive tower, naval guns | 34 | 14 | [3] |

| Hughes Reef | Dōngmén Jiāo (东门礁) | — | Đá Tư Nghĩa | Access channel, coastal fortifications, four defensive towers, harbor, multi-level military facility | 19 | 8 | [4] |

| Johnson South Reef | Chìguā Jiāo (赤瓜礁) | Mabini Reef | Đá Gạc Ma | Access channel, concrete plant, defensive towers, desalination pumps, fuel dump, multi-level military facility, possible radar facility | 27 | 11 | [5] |

| Mischief Reef | Měijì Jiāo (美济礁) | Panganiban Reef | Đá Vành Khăn | Airstrip (~3000m), access channel, fortified seawalls | 1,379 | 558 | [6] |

| Subi Reef | Zhǔbì Jiāo (渚碧礁) | Zamora Reef | Đá Xu Bi | Airstrip (~3000m), access channel, piers | 976 | 395 | [7] |

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Audio | |

| Video | |

Total reclaimed area by PRC on 7 reefs: approx. 13.5 square kilometres (5.2 sq mi)[citation needed]

Machinery used

[edit]The PRC used hundreds of dredges and barges including a giant self-propelled dredger, the Tian Jing Hao.[14][15] Built in 2009 in China, the Tian Jing Hao is a 127 m (417 ft) long seagoing cutter suction dredger designed by German engineering company Vosta LMG; (Lübecker Maschinenbau Gesellschaft (de)). At 6,017 gross tons, with a dredging capacity of 4500 m3/h, it is credited as being the largest of its type in Asia. It has been operating on Cuarteron Reef, the Gaven Reefs, and at Fiery Cross Reef.[16]

Strategic importance

[edit]More than half of the world's annual merchant fleet tonnage passes through the Strait of Malacca, Sunda Strait, and Lombok Strait, with the majority continuing on into the South China Sea. Tanker traffic through the Strait of Malacca leading into the South China Sea is more than three times greater than Suez Canal traffic, and well over five times more than the Panama Canal.[17] The People's Republic of China (PRC) has stated its unilateral claim to almost the entire body of water.[18]

Legal issues

[edit]Territorial waters of an artificial island

[edit]

As the Mischief and Subi Reefs were under water prior to reclamations, they are considered by the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) as "sea bed" in "international waters". Although the PRC had ratified a limited[19] UNCLOS III not allowing innocent passage of war ships, according to the UNCLOS III, features built on the sea bed cannot have territorial waters.[19]

2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling on the construction of artificial islands outside a state's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

[edit]UNCLOS contains the following provision:

Article 60(1) - In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State shall have the exclusive right to construct and to authorize and regulate the construction, operation and use of: (a) artificial islands

If China’s artificial islands fall within their EEZ then they would be within their rights to construct them (although this would still be subject to the environmental provisions of UNCLOS).

In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) reached a decision in the dispute between the Philippines and China, resolving the question of whether China’s artificial islands in the Spratly archipelago fell within its own EEZ. It was held that China’s EEZ did not extend to the Spratly chain, that China therefore lacked the authority to construct an artificial island in that region, and that China had subsequently infringed on the Philippines’ EEZ by their constructing and maintaining of an artificial island on Mischief Reef.[20] This violated the Philippines’ “exclusive right to construct and to authorize and regulate the construction, operation and use of… artificial islands” as stated in Article 60(1)(a) of UNCLOS.[21]

China disputed the outcome of the PCA’s decision, labelling it “null and void”.[22] China had argued that Taiping Island, which falls within its EEZ, should be classified as an ‘island’ under international law. This would have allowed China’s EEZ to be extended another 200nm from Taiping Island, as ‘islands’ are given the same status as mainland territory under UNCLOS. However, as Taiping Island was “incapable of self-sufficiently providing for a stable community of inhabitants, it fell under UNCLOS as a ‘rock’ rather than a naturally occurring island.”[23] This only gave China a 12nm territorial sea surrounding Taiping Island and meant they could not extend their EEZ to the Spratly archipelago.[24] Moreover, the mere creation of artificial islands is not enough to create an EEZ for which these islands can then fall within – as outlined in Article 60(8) of UNCLOS.

Environmental legal issues

[edit]The PRC has ratified UNCLOS III;[19] the convention establishes general obligations for safeguarding the marine environment and protecting freedom of scientific research on the high seas, and also creates an innovative legal regime for controlling mineral resource exploitation in deep seabed areas beyond national jurisdiction, through an International Seabed Authority and the common heritage of mankind principle.[25]

UNCLOS contains the following environmental commitments:

Article 192 - "States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment"

Article 194(2) - "States shall take all measures necessary to ensure that activities under their jurisdiction or control are so conducted as not to cause damage by pollution to other States and their environment"

Article 194(5) – "The measures taken in accordance with this Part shall include those necessary to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species and other forms of marine life"

In addition to UNCLOS, China is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity, which contains the following provision:

Article 3 - "States have… the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction"

China’s land reclamation efforts and creation of channels for ships has destroyed portions of reefs, killing coral and other organisms in the process. In the process of island building the sediment deposited on the reefs "can wash back into the sea, forming plumes that can smother marine life and could be laced with heavy metals, oil and other chemicals from the ships and shore facilities being built."[26]: 3 These plumes damage coral tissue and can block sunlight from organisms such as reef-building corals which are dependent on that sunlight to survive.[26]: 3

In the Spratly archipelago, China engaged in shallow-water dredging, removing "not only sand and gravel, but also the ecosystems of the lagoon and the reef flat, important parts of a reef."[26]: 4 The damaged reefs that Chinese dredgers gathered sand and gravel from "may not fully recover for up to 10 to 15 years."[26]: 5 The reefs where the dredged up sand and gravel gets placed on suffer obvious harm as coral can no longer grow on them with an artificial island now placed over the reef. Additionally, by placing artificial islands on top of reefs, fisheries are also harmed, as these reefs help replenish depleted fish stocks in the South China Sea’s coastal areas.[26]: 3, 6

The negative marine impact from China's artificial island building violates Articles 192 and 194(5) of UNCLOS. It also violates Article 194(2) of UNCLOS and Article 3 of the Convention on Biological Diversity as the artificial island creation has occurred outside of China’s EEZ and within that of other states. Therefore, the damage is to other states and their environment (per Article 194(2) of UNCLOS), and at the very least the damage is in an area beyond the limits of national jurisdiction (per Article 3 of the Convention on Biological Diversity).

Regional concept

[edit]According to Chinese sources, the concept was invented in 1972 by Vietnam's Bureau of Survey and Cartography of Vietnam under the Office of Premier Phạm Văn Đồng, which printed out "The World Atlas" and said, "The chain of islands from the Nansha and Xisha Islands to Hainan Island, Taiwan Island, the Penghu Islands and the Zhoushan Islands are shaped like a bow and constitute a Great Wall defending the China mainland."[27]

Reactions

[edit]States

[edit]- Australia – Opposed to "any coercive or unilateral actions to change the status quo in the South and East China Sea",[28] Australia continues to fly routine surveillance operations and exercise the right to freedom of navigation in international airspace "in accordance with the international civil aviation convention, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea."[29] Amid rising Australia-China diplomatic tensions in 2020, Australia strengthened its opposition by making a submission to the United Nations declaring the works are "completely unlawful" – following its ally the United States' position.[30]

- China – Following confrontations between US P8-A Poseidon aircraft and the Chinese Navy over the constructions in May 2015,[31] China stated that it has "the right to engage in monitoring in the relevant air space and waters to protect the country's sovereignty and prevent accidents at sea."[32]

- South Korea – No official stance, maintains an "increasingly notable silence on freedom of navigation in the South China Sea".[33][34]

- United States – The construction is considered to be a key motivating factor behind the Obama administration's "Asia Pivot" military strategy.[35] It believes "that China's activities in the South China Sea are driven by nationalism, part of a wider strategy aimed at undercutting US influence in Asia."[5] It has declared that it would operate military aircraft in the region "'in accordance with international law in disputed areas of the South China Sea' and would continue to do so 'consistent with the rights freedoms and lawful uses of the sea.'"[32]

- Since October 2015, when the USS Lassen passed close to man-made land built upon Subi Reef,[36] the US has been conducting freedom of navigation operations (FONOP) near the artificial islands approximately every three months using Arleigh Burke-class Guided missile destroyers.[37]

- In 2020 amid rising diplomatic and economic tensions in US-China relations, America declared that, "Beijing's claims to offshore resources across most of the South China Sea are completely unlawful, as is its campaign of bullying to control them."[38]

Organizations

[edit]- ASEAN – The Association of Southeast Asian Nations stated that the constructions "may undermine peace, security and stability" in the region as well as having strongly negative impact on the marine environment and fishery stocks.[39]

- G7 – In a "Declaration on maritime security" before the 41st G7 summit, the G7 stated that, "We continue to observe the situation in the East and South China Seas and are concerned by any unilateral actions, such as large scale land reclamation, which change the status quo and increase tensions. We strongly oppose any attempt to assert territorial or maritime claims through the use of intimidation, coercion or force.[40]

- In July 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague issued a decision stating that China has no historic title over the area.[41]

Ecological impact

[edit]

Aside from geo-political tensions, concerns have been raised about the environmental impact on fragile reef ecosystems through the destruction of habitat, pollution and interruption of migration routes.[12] These new islands are built on reefs previously one metre (3 ft) below the level of the sea. For back-filling these seven artificial islands, a total area of 13.5 square kilometres (5.2 sq mi), to the height of few meters, China had to destroy surrounding reefs and pump 40 to 50 million m3 (1.4 to 1.8 billion cu ft) of sand and corals, resulting in significant and irreversible damage to the environment. Frank Muller-Karger, professor of biological oceanography at the University of South Florida, said sediment "can wash back into the sea, forming plumes that can smother marine life and could be laced with heavy metals, oil and other chemicals from the ships and shore facilities being built." Such plumes threaten the biologically diverse reefs throughout the Spratlys, which Dr. Muller-Karger said may have trouble surviving in sediment-laden water.[42]

Rupert Wingfield-Hayes, visiting the vicinity of the Philippine-controlled island of Pagasa by plane and boat, said he saw Chinese fishermen poaching and destroying the reefs on a massive scale. As he saw Chinese fishermen poaching endangered species like massive giant clams, he noted "None of this proves China is protecting the poachers. But nor does Beijing appear to be doing anything to stop them. The poachers we saw showed absolutely no sign of fear when they saw our cameras filming them". He concludes: "However shocking the reef plundering I witnessed, it is as nothing compared to the environmental destruction wrought by China's massive island building programme nearby. The latest island China has just completed at Mischief Reef is more than 9km (six miles) long. That is 9km of living reef that is now buried under millions of tonnes of sand and gravel."[43]

A 2014 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report noted that "Sand is rarer than one thinks."[44] "The average price of sand imported by Singapore was US$3 per tonne from 1995 to 2001, but the price increased to US$190 per tonne from 2003 to 2005".[44] Although the Philippines and the PRC had both ratified the UNCLOS III,[19] in the case of Johnson South Reef, Hughes Reef and Mischief Reef, the PRC dredged sand for free in the EEZ the Philippines had claimed from 1978,[45] arguing this to be the "waters of China's Nansha Islands". "Although the consequences of substrate mining are hidden, they are tremendous. Aggregate particles that are too fine to be used are rejected by dredging boats, releasing vast dust plumes and changing water turbidity".[44]

John McManus, a professor of marine biology and ecology at the University of Miami said: "The worst thing anyone can do to a coral reef is to bury it under tons of sand and gravel ... There are global security concerns associated with the damage. It is likely broad enough to reduce fish stocks in the world's most fish-dependent region." He explained that the reason "the world has heard little about the damage inflicted by the People's Republic of China to the reefs is that the experts can't get to them", and noted "I have colleagues from the Philippines, Taiwan, PRC, Vietnam and Malaysia who have worked in the Spratly area. Most would not be able to get near the artificial islands except possibly some from PRC, and those would not be able to release their findings".[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Speech delivered to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute" (PDF). Commander, US Pacific Fleet. U.S. Navy. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ a b Wingfield-Hayes, Rupert (9 September 2014). "China's Island Factory". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "US Navy: Beijing creating a 'great wall of sand' in South China Sea". The Guardian. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (29 May 2015). "US-China tensions rise over Beijing's 'Great Wall of Sand'". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ a b Brown, James (6 June 2015). "China building islands, not bridges". The Saturday Paper. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (14 December 2016). "Images show 'significant' Chinese weapons systems in South China Sea". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "China building 'great wall of sand' in South China Sea". BBC. 1 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "China Voice: Drop fearmongering over South China Sea". news.xinhuanet.com. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "South China Sea dispute: What you need to know". Sydney Morning Herald. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Hardy, James; O'Connor, Sean (16 April 2015). "China's first runway in Spratlys under construction". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "China 'building runway in disputed South China Sea island'". BBC News. 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b Batongbacal, Jay (7 May 2015). "Environmental Aggression in the South China Sea". Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Land reclamation by country". Island Tracker. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Wingfield-Hayes, R. (9 September 2014). "China's Island Factory". BBC News. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Lee, V. R. (15 January 2016). "Satellite imagery shows ecocide in the South China Sea". DiploMat. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "China goes all out with major island building project in Spratlys". Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "South China Sea Oil Shipping Lanes". Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "China's new n-submarine base sets off alarm bells". IndianExpress. 3 May 2008. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d "UNCLOS. Declarations upon ratification". Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Adam W. Kohl, "China's Artificial Island Building Campaign in the South China Sea: Implications for the Reform of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea," Dickinson Law Review 122, no. 3 (Spring 2018): 933-934, https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/dknslr122&id=938&collection=journals&index=.

- ^ Adam W. Kohl, "China's Artificial Island Building Campaign in the South China Sea: Implications for the Reform of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea," Dickinson Law Review 122, no. 3 (Spring 2018): 933-934, https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/dknslr122&id=938&collection=journals&index=.

- ^ Sardor Allayarov, International Law with Chinese Characteristics - The South China Sea Territorial Dispute (Institute of International Relations Prague, 2023), 2, https://www.iir.cz/international-law-with-chinese-characteristics-the-south-china-sea-territorial-dispute.

- ^ Adam W. Kohl, "China's Artificial Island Building Campaign in the South China Sea: Implications for the Reform of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea," Dickinson Law Review 122, no. 3 (Spring 2018): 933, https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/dknslr122&id=938&collection=journals&index=; Tara Davenport, “Island-Building in the South China Sea: Legality and Limits,” Asian Journal of International Law 8, no. 1 (2018): 80, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2044251317000145.

- ^ Tara Davenport, “Island-Building in the South China Sea: Legality and Limits,” Asian Journal of International Law 8, no. 1 (2018): 83-84, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2044251317000145.

- ^ Jennifer Frakes, The Common Heritage of Mankind Principle and the Deep Seabed, Outer Space, and Antarctica: Will Developed and Developing Nations Reach a Compromise? Wisconsin International Law Journal. 2003; 21:409

- ^ a b c d e Southerland, Matthew (12 April 2016). "China's Island Building in the South China Sea: Damage to the Marine Environment, Implications, and International Law" (PDF). Washington D.C.: United States–China Economic and Security Review Commission. OCLC 948771539.

- ^ "The Operation of the HYSY 981 Drilling Rig: Vietnam's Provocation and China's Position". 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2016. : "1972年5月越南总理府测量和绘图局印制的《世界地图集》,用中国名称标注西沙群岛(见附件4)。1974年越南教育出版社出版的普通学校九年级《地理》教科书,在《中华人民共和国》一课(见附件5)中写道:“从南沙、西沙各岛到海南岛、台湾岛、澎湖列岛、舟山群岛,......这些岛呈弓形状,构成了保卫中国大陆的一座‘长城’。”"

- ^ Wroe, David; Wen, Philip (1 June 2015). "South China Sea dispute: Strong indication Australia will join push back on China's island-building". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Wroe, David; Wen, Phillip (15 December 2015). "South China Sea: Australia steps up air patrols in defiance of Beijing". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Visontay, Elias (25 July 2020). "Australia declares 'there is no legal basis' to Beijing's claims in South China Sea". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Sciutto, Jim (21 May 2015). "Exclusive: China warns U.S. surveillance plane". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b "South China Sea: China's navy told US spy plane flying over islands to leave 'eight times', CNN reports". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Kelly, Robert (7 July 2015). "South China Sea: Why Korea is silent, and why that's a good thing". The Interpreter. Lowy Institute for International Policy. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Van (24 June 2015). "The South China Sea Needs South Korea". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Callick, Rowan (22 May 2015). "US push-back in Asia gains momentum to reassure partners". The Australian. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ David Wroe and Philip Wen (31 October 2015). "South China Sea: Whose neighbourhood is it, anyway?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "US Navy carries out third FONOP in South China Sea". The Interpreter. Lowy Institute for International Policy. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea". United States Department of State. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Schofield, Clive (14 May 2015). "Why the world is wary of China's 'great wall of sand' - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "G7 Foreign Ministers' Declaration on Maritime Security". G8 Information Center. University of Toronto. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Harvey, Adam (13 July 2016). "Philippines celebrates victory in South China Sea case, despite China's refusal to accept result". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Watkins, Derek (27 October 2015). "What China Has Been Building in the South China Sea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017.

- ^ Wingfield-Hayes, Rupert (27 October 2015). "Why are Chinese fishermen destroying coral reefs in the South China Sea?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c "Sand, rarer than one thinks" (PDF). 1 March 2014. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ "Presidential Decree No. 1599 establishing an Exclusive Economic Zone and for other purposes". Chan Robles Law Library. 11 June 1978. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Clark, Colin (18 November 2015). "'Absolute Nightmare' as Chinese destroy South China Reefs; fish stocks at risk". breakingdefense.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

KSF

KSF