Hasdai Crescas

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Hasdai ben Abraham Crescas (Catalan: [həzˈðaj ˈβeɲ ʒuˈða ˈkɾeskəs]; Hebrew: חסדאי קרשקש; c. 1340 in Barcelona – 1410/11 in Zaragoza) was a Spanish-Jewish philosopher and a renowned halakhist (teacher of Jewish law). Along with Maimonides ("Rambam"), Gersonides ("Ralbag"), and Joseph Albo, he is known as one of the major practitioners of the rationalist approach to Jewish philosophy.[1]

Biography

[edit]

Hasdai Crescas came from a family of scholars. He was the grandson of the Talmudist Hasdai ben Judah Crescas, and a disciple of the Talmudist and philosopher Nissim of Gerona. Following his teacher's footsteps, he became a Talmudic authority and a philosopher of great originality. He is considered critical in the history of modern thought for his profound influence on Baruch Spinoza.[2]

After leaving Barcelona, he held the administrative position of crown rabbi of Aragon.[3] He seems to have been active as a teacher. Among his fellow students and friends, Isaac ben Sheshet, famous for his responsa, takes precedence. Joseph Albo is the best known of his pupils, but at least two others won recognition, Mattathias of Zaragoza and Zechariah ha-Levi.

Crescas was a man of means. As such, he was appointed sole executor of his uncle's will, Vitalis Azday, by King John I of Aragon in 1393. Still, though enjoying the high esteem even of prominent non-Jews, he did not escape their fate. Imprisoned with his teacher upon a false accusation of host desecration in 1378, he suffered personal indignities because he was a Jew. His only son was martyred in the massacre of 1391.

Notwithstanding this bereavement, his mental powers were unbroken. The works that have made him famous were written after that terrible year. In 1401-02 he visited Joseph Orabuena in Pamplona at the request of Charles III of Navarre, who paid the expenses of his journey to various Navarrese towns (Jacobs, l.c. Nos. 1570, 1574). He was at that time described as "Rav of Zaragoza."

Works

[edit]His works on Jewish law, if indeed he ever committed to writing, have not reached us. But his concise philosophical work, Or Adonai, The Light of the Lord, became a classical Jewish refutation of medieval Aristotelianism and a harbinger of the Scientific Revolution of the 16th century.

Three of his writings have been preserved:

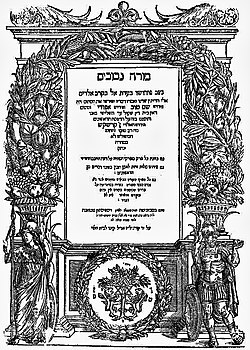

- His primary work, Or Adonai "Light of the Lord".

- An exposition and refutation of the central doctrines of Christianity. This treatise was written in 1398 in Old Catalan. The original is no longer extant, but a Hebrew translation by Joseph ibn Shem-Tov, with the title "Refutation of the Cardinal Principles of the Christians" has been preserved. The work was composed at the solicitation of Spanish noblemen. Crescas' object in writing what is virtually an apologetic treatise on Judaism was to present the reasons which held the Jews fast to their ancestral faith.

- His letter to the congregations of Avignon, published as an appendix to Wiener's edition of Shevet Yehudah of Solomon ibn Verga, in which he relates the incidents of the 1391 pogrom.

List of works

[edit]

- The Light of the Lord (Hebrew: Or Adonai or Or Hashem)

- The Refutation of the Christian Principles (polemics and some philosophy)

- Daniel Lasker: Sefer Bittul Iqqerei Ha-Nozrim by R. Hasdai Crescas. Albany 1992. ISBN 0-7914-0965-1

- Carlos del Valle Rodríguez: La inconsistencia de los dogmas cristianos: Biṭṭul 'Iqqare ha-Noṣrim le-R. Ḥasday Crescas. Madrid 2000. ISBN 84-88324-12-X

- Passover Sermon (religious philosophy and some halakha)

References

[edit]- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann, and Hirsch, Emil G. "Crescas, Hasdai ben Abraham". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls

- ^ Durant, Will (1926). The Story of Philosophy. New York, NY: Pocket Books. p. 149. ISBN 0-671-73916-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Berlin, Adele; Himelstein, Shmuel (2011). "Crown Rabbi". The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (2nd ed.). Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973004-9. Retrieved 31 May 2015. p. 194

Further reading

[edit]- Harry Austryn Wolfson, Crescas' Critique of Aristotle. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1929.

- Warren Zev Harvey, Physics and Metaphysics in Hasdai Crescas, Amsterdam Studies in Jewish Thought, J.C. Gieben, Amsterdam, 1998.

- Warren Zev Harvey, Great Spirit and Creativity within the Jewish Nation: Rabbi Hasdai Crescas(Hebrew), Mercaz, Zalman Shazar, Jerusalem 2010.

KSF

KSF