Henry Baker (naturalist)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

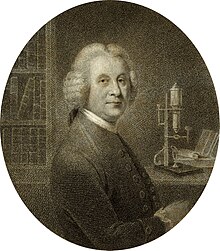

Henry Baker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 May 1698 |

| Died | 25 November 1774 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | London, England, United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | Microscopy |

| Children | David |

| Awards | (1744) Copley gold medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Naturalist |

Henry Baker (8 May 1698 – 25 November 1774) was a British naturalist.

Life

[edit]

He was born in Chancery Lane, London, 8 May 1698, the son of William Baker, a clerk in chancery. When he was 15, he was apprenticed to John Parker, a bookseller. At the close of his indentures in 1720, Baker went on a visit to John Forster, a relative, who had a deaf-mute daughter, then eight years old. As a successful therapist of deaf people, he went on to make money, by a system that he kept secret.[1] His work as therapist caught the attention of Daniel Defoe, whose youngest daughter Sophia he married on 30 April 1729.

In 1740, he was elected fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and of the Royal Society. In 1744, he received the Copley gold medal for microscopical observations on the crystallization of saline particles.

He was one of the founders of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce in 1754 (later the Society of Arts), and for some time acted as its secretary. He died in London, and was buried at St Mary le Strand.

Universal Spectator

[edit]Under the name of Henry Stonecastle, Baker was associated with Daniel Defoe in starting the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal in 1728. Defoe in fact did little except at the launch of the publication, intended as an essay-sheet rather than a newspaper. It appeared until 1746, running to 907 issues.[2] Baker's involvement as editor continued until 1733.[3] Among the major early contributors was the journalist John Kelly.[4]

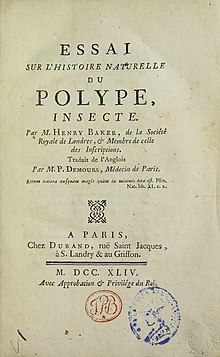

Works

[edit]He contributed many memoirs to the Transactions of the Royal Society. Among his publications were A Short History of Speech (1723), The Microscope made Easy (1743), Employment for the Microscope (1753),[5] where he noted down the presence of dinoflagellates for the first time as "Animalcules which cause the Sparkling Light in Sea Water", and several volumes of verse, original and translated, including The Universe, a Poem intended to restrain the Pride of Man (1727).[6][7]

Legacy

[edit]His name is perpetuated by the Bakerian Lecture of the Royal Society, for the foundation of which he left by will the sum of £100.

Literature

[edit]- George Rousseau. The Letters and Private Papers of Sir John Hill (New York: AMS Press, 1981). ISBN 0-404-61472-8. Provides much biographical material about Baker in the Royal Society, and his Monday and Wednesday club of FRS at his London house.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

[edit]- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1885). "Baker, Henry (1698–1774)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 9–10.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1885). "Baker, Henry (1698–1774)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 9–10.

- ^ The Universal Spectator (London 1728–1746): An Annotated Record of the Literary Contents. Edwin Mellen Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0-7734-6409-4.

- ^ Dr. Henry Baker Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine. penserians.cath.vt.edu

- ^ Watt, Francis (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 352.

- ^ Baker, M., 1753. Employment for the microscope. Dodsley, London, 403 pp.

- ^ G. Turner (2006), "Baker, Henry (1698–1774)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 8 May 2020: Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Baker's description of the polyp was translated into French by Pierre Demours in 1744 [1].

External links

[edit]- Baker, Henry (1743) An attempt towards a natural history of the polype, in a letter to Martin Folkes... Archived 8 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- Baker, Henry (1743) The microscope made easy Archived 8 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- Henry Baker collection at John Rylands Library, Manchester.

KSF

KSF