Historian

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 31 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 31 min

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it.[1] Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. Some historians are recognized by publications or training and experience.[2] "Historian" became a professional occupation in the late nineteenth century as research universities were emerging in Germany and elsewhere.

Objectivity

[edit]Among historians

[edit]Ancient historians

[edit]In the 19th century, scholars used to study ancient Greek and Roman historians to see how generally reliable they were. In recent decades, however, scholars have focused more on the constructions, genres, and meanings that ancient historians sought to convey to their audiences.[3] History is always written with contemporary concerns and ancient historians wrote their histories in response to the needs of their times.[3] Out of thousands of Greek and Roman historians, only the tiniest fraction's works survive and it is out of this small pool that ancient historians and ancient historiography are analyzed today.[3] Modern historians of the ancient world have to deal with diverse types of evidence, which are debated more today than in the 19th century due to innovations in the field.[4]

Ancient historians were very different from modern historians in terms of goals, documentation, sources, and methods.[5] For instance, chronological systems were not widely used, their sources were often absorbed (traceability of such sources usually disappeared), and the goal of an ancient work was often to create political or military paradigms. It was only after the emergence of Christianity that philosophies of history grew in prominence due to the destiny of man from the Christian account.[5] Epics such as Homer's works were used by historians and considered history even by Thucydides.[5] Ancient orators like Cicero stated that their historiographical narrative was divded into 3 divisions: history, argument, and fable.[6]

Modern historians

[edit]In the 19th-century historical studies became professionalized at universities and research centers along with a belief that history was a type of science.[7] However, in the 20th century historians incorporated social science dimensions like politics, economy, and culture in their historiography, including postmodernism.[7] Since the 1980s there has been a special interest in the memories and commemoration of past events.[8]

History by its nature is prone to continuous debate, and historians tend to be divided.[9] There is no past that is commonly agreed upon, since there are competing histories (e.g., of elites, non-elites, men, women, races, etc.).[10] It is widely accepted that "strict objectivity is epistemologically unattainable for historians".[11] Historians rarely articulate their conception of objectivity or discuss it in detail.[12] And like in other professions, historians rarely analyze themselves or their activity.[13] In practice, "specific canons of historical proof are neither widely observed nor generally agreed upon" among professional historians.[14] Though objectivity is often seen as the goal of those who work on history, in practice there is no convergence on anything in particular.[15] Historical scholarship is never value free since historian's writings are impacted by the frameworks of their times.[16] Some scholars of history have observed that there are no particular standards for historical fields such as religion, art, science, democracy, and social justice as these are by their nature 'essentially contested' fields, such that they require diverse tools particular to each field beforehand in order to interpret topics from those fields.[17]

There are three commonly held reasons why avoiding bias is not seen as possible in historical practice: a historian's interest inevitably influences their judgement (what information to use and omit, how to present the information, etc.); the sources used by historians for their history all have bias, and historians are products of their culture, concepts, and beliefs.[18] Racial and cultural biases can play major roles in national histories, which often ignore or downplay the roles on other groups.[19] Gender biases as well.[20][21] Moral or worldview evaluations by historians are also seen partly inevitable, causing complications for historians and their historical writings.[22][23] One way to deal with this is for historians to state their biases explicitly for their readers.[24] In the modern era, newspapers (which have a bias of their own) impacts historical accounts made by historians.[25] Wikipedia also contributes to difficulties for historians.[26]

Legal cases

[edit]During the Irving v Penguin Books and Lipstadt trial, the court relied on Richard Evan's witness report which mentioned "objective historian" in the same vein as the reasonable person, and reminiscent of the standard traditionally used in English law of "the man on the Clapham omnibus".[27] This was necessary so that there would be a legal benchmark to compare and contrast the scholarship of an objective historian against the illegitimate methods employed by David Irving, as before the Irving v Penguin Books and Lipstadt trial, there was no legal precedent for what constituted an objective historian.[27]

Justice Gray leant heavily on the research of one of the expert witnesses, Richard J. Evans, who compared illegitimate distortion of the historical record practiced by Holocaust deniers with established historical methodologies.[28]

By summarizing Gray's judgment, in an article published in the Yale Law Journal, Wendie E. Schneider distils these seven points for what he meant by an objective historian:[29]

- The historian must treat sources with appropriate reservations;

- The historian must not dismiss counter-evidence without scholarly consideration;

- The historian must be even-handed in treatment of evidence and eschew "cherry-picking";

- The historian must clearly indicate any speculation;

- The historian must not mistranslate documents or mislead by omitting parts of documents;

- The historian must weigh the authenticity of all accounts, not merely those that contradict their favored view; and

- The historian must take the motives of historical actors into consideration.

Schneider uses the concept of the "objective historian" to suggest that this could be an aid in assessing what makes a historian suitable as expert witnesses under the Daubert standard in the United States. Schneider proposed this, because, in her opinion, Irving could not have passed the standard Daubert tests unless a court was given "a great deal of assistance from historians".[30]

Schneider proposes that by testing a historian against the criteria of the "objective historian" then, even if a historian holds specific political views (and she gives an example of a well-qualified historian's testimony that was disregarded by a United States court because he was a member of a feminist group), providing the historian uses the "objective historian" standards, they are a "conscientious historian". It was Irving's failure as an "objective historian" not his right-wing views that caused him to lose his libel case, as a "conscientious historian" would not have "deliberately misrepresented and manipulated historical evidence" to support his political views.[31]

History analysis

[edit]The process of historical analysis involves investigation and analysis of competing ideas, facts, and purported facts to create coherent narratives that explain "what happened" and "why or how it happened". Modern historical analysis usually draws upon other social sciences, including economics, sociology, politics, psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and linguistics. While ancient writers do not normally share modern historical practices, their work remains valuable for its insights within the cultural context of the times. An important part of the contribution of many modern historians is the verification or dismissal of earlier historical accounts through reviewing newly discovered sources and recent scholarship or through parallel disciplines like archaeology.

Historiography

[edit]Ancient

[edit]

Understanding the past appears to be a universal human need, and the telling of history has emerged independently in civilizations around the world. What constitutes history is a philosophical question (see philosophy of history). The earliest chronologies date back to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, though no historical writers in these early civilizations were known by name.

Systematic historical thought emerged in ancient Greece, a development that became an important influence on the writing of history elsewhere around the Mediterranean region. The earliest known critical historical works were The Histories, composed by Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484 – c. 425 BCE) who later became known as the "father of history" (Cicero). Herodotus attempted to distinguish between more and less reliable accounts and personally conducted research by travelling extensively, giving written accounts of various Mediterranean cultures. Although Herodotus' overall emphasis lay on the actions and characters of men, he also attributed an important role to divinity in the determination of historical events. Thucydides largely eliminated divine causality in his account of the war between Athens and Sparta, establishing a rationalistic element that set a precedent for subsequent Western historical writings. He was also the first to distinguish between cause and immediate origins of an event, while his successor Xenophon (c. 431 – 355 BCE) introduced autobiographical elements and character studies in his Anabasis.

The Romans adopted the Greek tradition. While early Roman works were still written in Greek, the Origines, composed by the Roman statesman Cato the Elder (234–149 BCE), was written in Latin, in a conscious effort to counteract Greek cultural influence. Strabo (63 BCE – c. 24 CE) was an important exponent of the Greco-Roman tradition of combining geography with history, presenting a descriptive history of peoples and places known to his era. Livy (59 BCE – 17 CE) records the rise of Rome from city-state to empire. His speculation about what would have happened if Alexander the Great had marched against Rome represents the first known instance of alternate history.[32]

In Chinese historiography, the Classic of History is one of the Five Classics of Chinese classic texts and one of the earliest narratives of China. The Spring and Autumn Annals, the official chronicle of the State of Lu covering the period from 722 to 481 BCE, is among the earliest surviving Chinese historical texts arranged on annalistic principles. Sima Qian (around 100 BCE) was the first in China to lay the groundwork for professional historical writing. His written work was the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), a monumental lifelong achievement in literature. Its scope extends as far back as the 16th century BCE, and it includes many treatises on specific subjects and individual biographies of prominent people and also explores the lives and deeds of commoners, both contemporary and those of previous eras.[33]

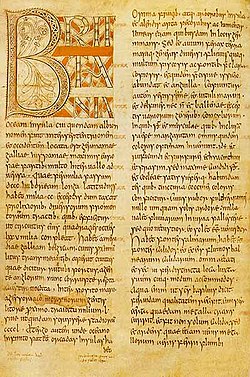

Christian historiography began early, perhaps as early as Luke-Acts, which is the primary source for the Apostolic Age. Writing history was popular among Christian monks and clergy in the Middle Ages. They wrote about the history of Jesus Christ, that of the Church and that of their patrons, the dynastic history of the local rulers. In the Early Middle Ages historical writing often took the form of annals or chronicles recording events year by year, but this style tended to hamper the analysis of events and causes.[34] An example of this type of writing is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, which were the work of several different writers: it was started during the reign of Alfred the Great in the late ninth century, but one copy was still being updated in 1154.[citation needed]

Muslim historical writings first began to develop in the seventh century, with the reconstruction of the Prophet Muhammad's life in the centuries following his death. With numerous conflicting narratives regarding Muhammad and his companions from various sources, scholars had to verify which sources were more reliable. To evaluate these sources, they developed various methodologies, such as the science of biography, science of hadith and Isnad (chain of transmission). They later applied these methodologies to other historical figures in the Islamic civilization. Famous historians in this tradition include Urwah (d. 712), Wahb ibn Munabbih (d. 728), Ibn Ishaq (d. 761), al-Waqidi (745–822), Ibn Hisham (d. 834), Muhammad al-Bukhari (810–870) and Ibn Hajar (1372–1449).

Enlightenment

[edit]During the Age of Enlightenment, the modern development of historiography through the application of scrupulous methods began.

French philosophe Voltaire (1694–1778) had an enormous influence on the art of history writing. His best-known histories are The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). "My chief object," he wrote in 1739, "is not political or military history, it is the history of the arts, of commerce, of civilization – in a word, – of the human mind."[35] He broke from the tradition of narrating diplomatic and military events, and emphasized customs, social history, and achievements in the arts and sciences. He was the first scholar to make a serious attempt to write the history of the world, eliminating theological frameworks, and emphasizing economics, culture, and political history.

At the same time, philosopher David Hume was having a similar impact on history in Great Britain. In 1754, he published the History of England, a six-volume work that extended from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688. Hume adopted a similar scope to Voltaire in his history; as well as the history of Kings, Parliaments, and armies, he examined the history of culture, including literature and science, as well.[36] William Robertson, a Scottish historian, and the Historiographer Royal[37] published the History of Scotland 1542 – 1603, in 1759 and his most famous work, The history of the reign of Charles V in 1769.[38] His scholarship was painstaking for the time and he was able to access a large number of documentary sources that had previously been unstudied. He was also one of the first historians who understood the importance of general and universally applicable ideas in the shaping of historical events.[39]

The apex of Enlightenment history was reached with Edward Gibbon's, monumental six-volume work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published on 17 February 1776. Because of its relative objectivity and heavy use of primary sources, at the time its methodology became a model for later historians. This has led to Gibbon being called the first "modern historian".[40] The book sold impressively, earning its author a total of about £9000. Biographer Leslie Stephen wrote that thereafter, "His fame was as rapid as it has been lasting."

19th century

[edit]The tumultuous events surrounding the French Revolution inspired much of the historiography and analysis of the early 19th century. Interest in the 1688 Glorious Revolution was also rekindled by the Great Reform Act of 1832 in England.

Thomas Carlyle published his magnum opus, the three-volume The French Revolution: A History in 1837.[41][42] The resulting work had a passion new to historical writing. Thomas Macaulay produced his most famous work of history, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, in 1848.[43] His writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with the freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history.[44]

In his main work Histoire de France, French historian Jules Michelet coined the term Renaissance (meaning "Re-birth" in French language), as a period in Europe's cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages, creating a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.[45] The nineteen-volume work covered French history from Charlemagne to the outbreak of the Revolution. Michelet was one of the first historians to shift the emphasis of history to the common people, rather than the leaders and institutions of the country. Another important French historian of the period was Hippolyte Taine. He was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Literary historicism as a critical movement has been said to originate with him.[46]

One of the major progenitors of the history of culture and art, was the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt[47] Burckhardt's best-known work is The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860). According to John Lukacs, he was the first master of cultural history, which seeks to describe the spirit and the forms of expression of a particular age, a particular people, or a particular place.[48] By the mid-19th century, scholars were beginning to analyse the history of institutional change, particularly the development of constitutional government. William Stubbs's Constitutional History of England (3 vols., 1874–78) was an important influence on this developing field. The work traced the development of the English constitution from the Teutonic invasions of Britain until 1485, and marked a distinct step in the advance of English historical learning.[49]

Karl Marx introduced the concept of historical materialism into the study of world-historical development. In his conception, the economic conditions and dominant modes of production determined the structure of society at that point. Previous historians had focused on the cyclical events of the rise and decline of rulers and nations. Process of nationalization of history, as part of national revivals in the 19th century, resulted with separation of "one's own" history from common universal history by such way of perceiving, understanding and treating the past that constructed history as history of a nation.[50] A new discipline, sociology, emerged in the late 19th century and analyzed and compared these perspectives on a larger scale.

Professionalization in Germany

[edit]

The modern academic study of history and methods of historiography were pioneered in 19th-century German universities. Leopold von Ranke was a pivotal influence in this regard, and is considered as the founder of modern source-based history.[51][52][53][54]

Specifically, he implemented the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and analysis of historical documents. Beginning with his first book in 1824, the History of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494 to 1514, Ranke used an unusually wide variety of sources for a historian of the age, including "memoirs, diaries, personal and formal missives, government documents, diplomatic dispatches and first-hand accounts of eye-witnesses". Over a career that spanned much of the century, Ranke set the standards for much of later historical writing, introducing such ideas as reliance on primary sources (empiricism), an emphasis on narrative history and especially international politics (aussenpolitik).[55] Sources had to be hard, not speculations and rationalizations. His credo was to write history the way it was. He insisted on primary sources with proven authenticity.[56]

20th century

[edit]The term Whig history was coined by Herbert Butterfield in his short book The Whig Interpretation of History in 1931, (a reference to the British Whigs, advocates of the power of Parliament) to refer to the approach to historiography that presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasized the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms, and scientific progress. The term has been also applied widely in historical disciplines outside of British history (the history of science, for example) to criticize any teleological (or goal-directed), hero-based, and transhistorical narrative.[57] Butterfield's antidote to Whig history was "...to evoke a certain sensibility towards the past, the sensibility which studies the past 'for the sake of the past', which delights in the concrete and the complex, which 'goes out to meet the past', which searches for 'unlikenesses between past and present'."[58] Butterfield's formulation received much attention, and the kind of historical writing he argued against in generalised terms is no longer academically respectable.[59]

The French Annales School radically changed the focus of historical research in France during the 20th century by stressing long-term social history, rather than political or diplomatic themes. The school emphasized the use of quantification and the paying of special attention to geography.[60][61] An eminent member of this school, Georges Duby, described his approach to history as one that

relegated the sensational to the sidelines and was reluctant to give a simple accounting of events, but strived on the contrary to pose and solve problems and, neglecting surface disturbances, to observe the long and medium-term evolution of economy, society, and civilisation.

Marxist historiography developed as a school of historiography influenced by the chief tenets of Marxism, including the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. Friedrich Engels wrote The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which was salient in creating the socialist impetus in British politics from then on, e.g. the Fabian Society. R. H. Tawney's The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (1912)[62] and Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1926), reflected his ethical concerns and preoccupations in economic history. A circle of historians inside the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) formed in 1946 and became a highly influential cluster of British Marxist historians, who contributed to history from below and class structure in early capitalist society. Members included Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm and E. P. Thompson.

World history, as a distinct field of historical study, emerged as an independent academic field in the 1980s. It focused on the examination of history from a global perspective and looked for common patterns that emerged across all cultures. Arnold J. Toynbee's ten-volume A Study of History, written between 1933 and 1954, was an important influence on this developing field. He took a comparative topical approach to independent civilizations and demonstrated that they displayed striking parallels in their origin, growth, and decay.[63] William H. McNeill wrote The Rise of the West (1965) to improve upon Toynbee by showing how the separate civilizations of Eurasia interacted from the very beginning of their history, borrowing critical skills from one another, and thus precipitating still further change as adjustment between traditional old and borrowed new knowledge and practice became necessary.[64]

Historical editing

[edit]A new advanced specialty opened in the late 20th century: historical editing. Edmund Morgan reports on its emergence in the United States:[65]

It required, to begin with, large sums of money. But money has proved easier to recruit than talent. Historians who undertake these large editorial projects must leave the main channel of academic life. They do not teach; they do not write their own books; they do not enjoy long vacations for rumination, reflection, and research on whatever topic interests them at the moment. Instead they must live in unremitting daily pursuit of an individual whose company, whatever his genius, may ultimately begin to pall. Anyone who has edited historical manuscripts knows that it requires as much physical and intellectual labor to prepare a text for publication as it does to write a book of one's own. Indeed, the new editorial projects are far too large for one man. The editor-in-chief, having decided to forego a regular academic career, must entice other scholars to help him; and with the present [high] demand for college teachers, this is no easy task.

Education and profession

[edit]

An undergraduate history degree is often used as a stepping stone to graduate studies in business or law. Many historians are employed at universities and other facilities for post-secondary education.[66] In addition, it is normal for colleges and universities to require a PhD degree for new full-time hires. A scholarly thesis, such as a doctoral dissertation, is now regarded as the baseline qualification for a professional historian. However, some historians still gain recognition based on published (academic) works and the award of fellowships by academic bodies like the Royal Historical Society. Publication is increasingly required by smaller schools, so graduate papers become journal articles and PhD dissertations become published monographs. The graduate student experience is difficult—those who finish their doctorate in the United States take on average 8 or more years; funding is scarce except at a few very rich universities. [citation needed] Being a teaching assistant in a course is required in some programs; in others it is a paid opportunity awarded a fraction of the students. Until the 1970s it was rare for graduate programs to teach how to teach; the assumption was that teaching was easy and that learning how to do research was the main mission.[67][68] A critical experience for graduate students is having a mentor who will provide psychological, social, intellectual and professional support, while directing scholarship and providing an introduction to the profession.[69]

Professional historians typically work in colleges and universities, archival centers, government agencies, museums, and as freelance writers and consultants.[70] The job market for new PhDs in history is poor and getting worse, with many relegated to part-time "adjunct" teaching jobs with low pay and no benefits.[71]

"Amateur" historians

[edit]C. Vann Woodward (1908–1999), Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, cautioned that the academicians had themselves abdicated their role as storytellers:

Professionals do well to apply the term "amateur" with caution to the historian outside their ranks. The word does have deprecatory and patronizing connotations that occasionally backfire. This is especially true of narrative history, which nonprofessionals have all but taken over. The gradual withering of the narrative impulse in favor of the analytical urge among professional academic historians has resulted in a virtual abdication of the oldest and most honored role of the historian, that of storyteller. Having abdicated... the professional is in a poor position to patronize amateurs who fulfill the needed function he has abandoned.[72]

See also

[edit]- List of historians

- Antiquarian – Specialist or aficionado of antiquities or things of the past

- Auxiliary sciences of history – Scholarly disciplines in historical research

- Historiography – Study of the methods used by historians

- Historical revisionism – Reinterpretation of a historical account

- Historical negationism – Illegitimate distortion of the historical record

- Professionalization and institutionalization of history - term in historiography

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Historian". Wordnetweb.princeton.edu. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Herman, A. M. (1998). Occupational outlook handbook: 1998–99 edition. Indianapolis: JIST Works. Page 525.

- ^ a b c Marincola, John (September 2007). "Introduction". In Marincola, John (ed.). A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. xvii–xix, xxiii. doi:10.1002/9781405185110. ISBN 978-1-4051-0216-2.

- ^ Finley, M.I. (2008). Ancient History: Evidence and Models. ACLS History. p. 7. ISBN 978-1597405348.

I believe the nature and uses of the evidence about antiquity are being debated more widely and determinedly today than at any time since...the early nineteenth century. Partly this is a consequence of the exponential increase in the quantity of available archaeological information and in the quantity of publications generally in ancient studies, and partly it reflects new approaches to the study of history, new interests and the formulation of new questions.

- ^ a b c Nicolai, Roberto (September 2007). "The Place of History in the Ancient World". A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 3–5, 7. doi:10.1002/9781405185110.ch1. ISBN 978-1-4051-0216-2.

- ^ Cicero. "On Invention Book I, Chapter XIX". Loeb Classical Library.

- ^ a b Georg G. Iggers, Historiography in the Twentieth Century: From Scientific Objectivity to the Postmodern Challenge, 1-4. ISBN 978-0819567666

- ^ David Glassberg, "Public history and the study of memory." The Public Historian 18.2 (1996): 7–23 online Archived 2020-02-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gilderhus, Mark (2009). History and Historians: A Historiographical Introduction. Pearson. p. 81. ISBN 9780205687534.

Even so, what critics might regard as disorder and disarray, historians would view as a sign of intellectual vitality. The body of literature on almost any historical subject takes the form of an ongoing debate.... After all, historians traditionally have investigated all sorts of human matters charged by passion and emotion. By the very nature of the subject, history tends to divide scholars and set them at odds.

- ^ Gilderhus, Mark (2009). History and Historians: A Historiographical Introduction. Pearson. p. 107. ISBN 9780205687534.

We no longer possess a past commonly agreed upon. Indeed, we have a multiplicity of versions competing for attention and emphasizing alternatively elites and nonelites, men and women, whites and persons of color, and no good way of reconciling all the differences.

- ^ Førland, Tor Egil (2017). Values, Objectivity, and Explanation in Historiography. New York: Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781315470979.

It is widely accepted that strict objectivity is epistemologically unattainable for historians, no matter how conscientious they are. I shall not contest this basic philosophical tenet, the implication of which is that all historiography is to some extent political in a wide sense of the term, taken to include (moral) values and worldviews.

- ^ Novick, Peter (1990). That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780521357456.

- ^ Finley, M.I. (2008). Ancient History: Evidence and Models. ACLS History. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1597405348.

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1970). Historians' Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 62. ISBN 9780061315459.

- ^ Novick, Peter (1990). That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 628. ISBN 9780521357456.

As a broad community of discourse, as a community of scholars united by common aims, common standards, and common purposes, the discipline of history had ceased to exist. Convergence on anything, let alone a subject as highly charged as "the objectivity question," was out of the question. The profession was as described in the last verse of the Book of Judges. "In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes." How long "those days" will continue is anyone's guess.

- ^ Iggers, Georg G. (October 2005). "Historiography in the Twentieth Century". History and Theory. 44 (3): 475. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2005.00337.x.

Historical scholarship is never value-free and historians not only hold political ideas that color their writing, but also work within the framework of institutions that affect the ways in which they write history.

- ^ McCullagh, C. Behan (2000). "Bias in Historical Description, Interpretation, and Explanation". History and Theory. 39 (1): 47. doi:10.1111/0018-2656.00112. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2677997.

W. B. Gallie argued that some concepts in history are "essentially contested," namely "religion," "art," "science," "democracy," and "social justice." These are concepts for which "there is no one use of any of them which can be set up as its generally accepted and therefore correct or standard use. When historians write the history of these subjects, they must choose an interpretation of the subject to guide them. For instance, in deciding what Art is, historians can choose between "configurationist theories, theories of aesthetic contemplation and response .. ., theories of art as expression, theories emphasizing traditional artistic aims and standards, and communication theories.

- ^ McCullagh, C. Behan (2000). "Bias in Historical Description, Interpretation, and Explanation". History and Theory. 39 (1): 52. doi:10.1111/0018-2656.00112. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2677997.

Clearly bias in history should be avoided. But can it be? Can a historian's social responsibility of providing fair descriptions, interpretations, and explanations of social events be fulfilled? There are three commonly held reasons for denying the possibility of avoiding bias in history. The first is that historians' interests will inevitably influence their judgment in deciding how to conceive of a historical subject, in deciding what information to select for inclusion in their history of it, and in choosing words with which to present it. The second is the belief that, just as a historian's account of the past is inevitably biased, so too are the reports of events by contemporaries upon which historians rely. Some think there is no objective information about historical events which historians can use to describe them. The third is that, even if historians' individual biases can be corrected, and even if facts about the past can be known, historians are still products of their culture, of its language, concepts, beliefs, and attitudes, so that the possibility of an impartial, fair description of past events still remains unattainable.

- ^ Forbes, Jack D. (April 1963). "The Historian and the Indian: Racial Bias in American History". The Americas. 19 (4): 349–362. doi:10.2307/979504. JSTOR 979504.

- ^ Armitage, Sue (2009). "Are We There Yet?: Some Thoughts on the Current State of Western Women's History". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 59 (3): 70–96. ISSN 0026-9891. JSTOR 40543655.

- ^ Coughlin, Mimi (2007). "Women and History: Outside the Academy". The History Teacher. 40 (4): 471–479. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 30037044.

- ^ Vann, Richard T. (2004). "Historians and Moral Evaluations". History and Theory. 43 (4): 26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00295.x. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 3590633.

My analysis has already, I hope, established that there is an irreducible element of moral evaluation in historiography. It can be found in teaching, in all preparations for research, and finally in the finished text. It is complex, because it involves both appraisals of other historians, by standards that are generally agreed upon, yet inevitably also of the historical agents about whom they written, by standards that are eminently contestable.

- ^ Gregory, Brad S. (2006). "The Other Confessional History: On Secular Bias in the Study of Religion". History and Theory. 45 (4): 132–149. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2006.00388.x. ISSN 0018-2656.

- ^ Williams, Robert C. (2020). The Historian's Toolbox: A Student's Guide to the Theory and Craft of History (Fourth ed.). Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 9781138632172.

- ^ Muir, Edward (March 14, 2023). "Journalists and Historians". Perspectives on History. American Historical Association.

- ^ Bergen, Sadie (September 1, 2016). "Linking In: How Historians Are Fighting Wikipedia's Biases". Perspectives on History. American Historical Association.

- ^ a b Schneider 2001, p. 1531.

- ^ Schneider 2001, p. 1534.

- ^ Schneider 2001, pp. 1534, 1535.

- ^ Schneider 2001, pp. 1534, 1538.

- ^ Schneider 2001, pp. 15333, 1539.

- ^ "Livy's History of Rome: Book 9". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Jörn Rüsen (2007). Time and History: The Variety of Cultures. Berghahn Books. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-84545-349-7.

- ^ Warren, John (1998). The past and its presenters: an introduction to issues in historiography, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-67934-4, pp. 78–79.

- ^ E. Sreedharan (2004). A Textbook of Historiography: 500 BC to AD 2000. Orient Blackswan. p. 115. ISBN 9788125026570.

- ^ Wertz, S. K. (1993). "Hume and the Historiography of Science". Journal of the History of Ideas. 54 (3): 411–436. doi:10.2307/2710021. JSTOR 2710021.

- ^ "The Poker Club | James Boswell .info". www.jamesboswell.info.

- ^ Sher, R. B., Church and Society in the Scottish Enlightenment: The Moderate Literati of Edinburgh, Princeton, 1985.

- ^ Adamson Hoebel, E. (1960). "William Robertson: An 18th Century Anthropologist-Historian" (PDF). American Anthropologist. Archived from the original (PDF) on Jan 8, 2014. Retrieved 2012-12-17 – via American Anthropological Association.

- ^ Deborah Parsons (2007). Theorists of the Modernist Novel: James Joyce, Dorothy Richardson and Virginia Woolf. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 9780203965894.

- ^ Marshall, H.E. "Carlyle – The Sage Of Chelsea". English Literature For Boys And Girls. Retrieved 2009-09-19 – via Farlex Free Library.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (2009-09-20). "Thomas Carlyle". Professional Works. Criminal Brief. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ Macaulay, Thomas Babington, History of England. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1878. Vol. V, title page and prefatory "Memoir of Lord Macaulay".

- ^ J. R. Western, Monarchy and Revolution. The English State in the 1680s (London: Blandford Press, 1972), p. 403.

- ^ Brotton, Jerry (2002). The Renaissance Bazaar. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Kelly, R. Gordon, "Literature and the Historian", American Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1974), 143.

- ^ "Jacob Burckhardt The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy Cultural history". www.age-of-the-sage.org.

- ^ John Lukacs, Remembered Past: John Lukacs on History, Historians, and Historical Knowledge, ed. Mark G Malvasi and Jeffrey O. Nelson, Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2004, 215.

- ^ s:A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature/Stubbs, William

- ^ Georgiy Kasianov, Philipp Terr (2010-04-07). A Laboratory of Transnational History Ukraine and recent Ukrainian historiography. Berghahn Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84545-621-4. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

This essay deals with, what I call, "nationalized history", meaning a way of perceiving, understanding and treating the past that requires separation of "one's own" history from "common" history and its construction as history of a nation.

- ^ Frederick C. Beiser (2011) The German Historicist Tradition, p.254

- ^ Janelle G. Reinelt, Joseph Roach (2007), Critical Theory and Performance, p. 193

- ^ Stern (ed.), The Varieties of History, p. 54: "Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) is the father as well as the master of modern historical scholarship."

- ^ Green and Troup (eds.), The Houses of History, p. 2: "Leopold von Ranke was instrumental in establishing professional standards for historical training at the University of Berlin between 1824 and 1871."

- ^ E. Sreedharan, A textbook of historiography, 500 BC to AD 2000 (2004) p 185

- ^ Andreas Boldt, "Ranke: objectivity and history." Rethinking History 18.4 (2014): 457–474.

- ^ Ernst Mayr, "When Is Historiography Whiggish?" Journal of the History of Ideas, April 1990, Vol. 51 Issue 2, pp 301–309 in JSTOR

- ^ Adrian Wilson and T. G. Ashplant, "Whig History and Present-Centred History", The Historical Journal, 31 (1988): 1–16, at p. 10.

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan (1992), p. 208.

- ^ Lucien Febvre, La Terre et l'évolution humaine (1922), translated as A Geographical Introduction to History (London, 1932).

- ^ "Les Éditions de l'EHESS: Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales". www.editions.ehess.fr.

- ^ William Rose Benét (1988) p. 961

- ^ William H. McNeill, Arnold J. Toynbee a Life (1989)

- ^ McNeill, William H. (1995). "The Changing Shape of World History". History and Theory. 34 (2): 8–26. doi:10.2307/2505432. JSTOR 2505432.

- ^ Edmund S. Morgan, "John Adams and the Puritan Tradition." New England Quarterly 34#4 (1961): 518–529 at p. 519.

- ^ "Social Scientists, Other". Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2008–09 Edition. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009.

- ^ Michael Kammen, "Some Reminiscences and Reflections on Graduate Education in History, Reviews in American History Volume 36, Number 3, Sept 2008 pp. 468–484 doi:10.1353/rah.0.0027

- ^ Walter Nugent, "Reflections: "Where Have All the Flowers Gone . . . When Will They Ever Learn?", Reviews in American History Volume 39, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 205–211 doi:10.1353/rah.2011.0055

- ^ Michael Kammen, "On Mentoring Apprentice Historians and Appreciating Mentors—Gleaned From the Memories of Others." Reviews in American History 40.2 (2012): 339–348. online

- ^ Anthony Grafton and Robert B. Townsend, "The Parlous Paths of the Profession" Perspectives on History (Sept. 2008) online

- ^ Robert B. Townsend and Julia Brookins, "The Troubled Academic Job Market for History." Perspectives on History (2016) 54#2 pp 157–182 echoes Robert B. Townsend, "Troubling News on Job Market for History PhDs", AHA Today Jan. 4, 2010 online Archived 2011-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ C. Vann Woodward, "The Great American Butchery", New York Review of Books (March 6, 1975) online.

Sources

[edit]- Schneider, Wendie Ellen (June 2001). "Past Imperfect: Irving v. Penguin Books Ltd., No. 1996-I-1113, 2000 WL 362478 (Q. B. Apr. 11), appeal denied (Dec. 18, 2000)" (PDF). The Yale Law Journal. 110 (8): 1531–1545. doi:10.2307/797584. JSTOR 797584. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013.

- Vidor, Gian Marco (2015). "Emotions and writing the history of death. An interview with Michel Vovelle, Régis Bertrand and Anne Carol". Mortality. 20 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1080/13576275.2014.984485. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0026-B624-9.

Further reading

[edit]- The American Historical Association's Guide to Historical Literature ed. by Mary Beth Norton and Pamela Gerardi (3rd ed. 2 vol, Oxford U.P. 1995) 2064 pages; annotated guide to 27,000 of the most important English language history books in all fields and topics vol 1 online, vol 2 online

- Allison, William Henry. A guide to historical literature (1931) comprehensive bibliography for scholarship to 1930. online edition

- Barnes, Harry ElmerA history of historical writing (1962)

- Barraclough, Geoffrey. History: Main Trends of Research in the Social and Human Sciences, (1978)

- Bentley, Michael. ed., Companion to Historiography, Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415030846 pp; 39 chapters by experts

- Bender, Thomas, et al. The Education of Historians for Twenty-first Century (2003) report by the Committee on Graduate Education of the American Historical Association

- Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval and Modern, 3rd edition, 2007, ISBN 0-226-07278-9

- Boia, Lucian et al., eds. Great Historians of the Modern Age: An International Dictionary (1991)

- Cannon, John, et al., eds. The Blackwell Dictionary of Historians. Blackwell Publishers, 1988 ISBN 0-631-14708-X.

- Gilderhus, Mark T. History and Historians: A Historiographical Introduction, 2002, ISBN 0-13-044824-9

- Iggers, Georg G. Historiography in the 20th Century: From Scientific Objectivity to the Postmodern Challenge (2005)

- Kelly, Boyd, ed. Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing. (1999). Fitzroy Dearborn ISBN 1-884964-33-8

- Kramer, Lloyd, and Sarah Maza, eds. A Companion to Western Historical Thought Blackwell 2006. 520pp; ISBN 978-1-4051-4961-7.

- Todd, Richard B. ed. Dictionary of British Classicists, 1500–1960, (2004). Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum, 2004 ISBN 1-85506-997-0.

- Woolf D. R. A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities) (2 vol 1998) excerpt and text search

External links

[edit]- Selected texts by the most known historians Archived 2010-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

KSF

KSF