-

Former Union Minister for Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Shri Sharad Yadav delivering his inaugural speech at Regional Seminar on National Food Agencies "Challenges of the New Millennium" in New Delhi

-

Ram Vilas Paswan as the Union Minister of Chemicals & Fertilizers and Steel, addressing at "India Chem 2008" Industry meet in Mumbai on 10 June 2008.

History of Bihar

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 51 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 51 min

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

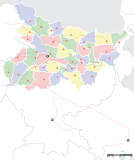

The History of Bihar is one of the most varied in India. Bihar consists of three distinct regions, each has its own distinct history and culture. They are Magadha, Mithila and Bhojpur.[1]Chirand, on the northern bank of the Ganga River, in Saran district, has an archaeological record dating from the Neolithic age (c. 2500 – 1345 BC).[2][3] Regions of Bihar—such as Magadha, Mithila and Anga—are mentioned in religious texts and epics of ancient India. Mithila is believed to be the centre of Indian power in the Later Vedic period (c. 1100 – 500 BC). Mithila first gained prominence after the establishment of the ancient Videha Kingdom.[4] The kings of the Videha were called Janakas. A daughter of one of the Janaks of Mithila, Sita, is mentioned as consort of Lord Rama in the Hindu epic Ramayana.[5] The kingdom later became incorporated into the Vajjika League which had its capital in the city of Vaishali, which is also in Mithila.[6]

Magadha was the centre of Indian power, learning and culture for about a thousand years. One of India's greatest empires, the Maurya Empire, as well as two major pacifist religions, Buddhism and Jainism, arose from the region that is now Bihar.[7] Empires of the Magadha region, most notably the Maurya and Gupta Empire, unified large parts of the Indian subcontinent under their rule.[8] Their capital Pataliputra, adjacent to modern-day Patna, was an important political, military and economic centre of Indian civilisation during the ancient and classical periods of Indian history. Many ancient Indian texts, aside from religious epics, were written in ancient Bihar. The play Abhijñānaśākuntala being the most prominent.

The present-day region of Bihar overlaps with several pre-Mauryan kingdoms and republics, including Magadha, Anga and the Vajjika League of Mithila. The latter was one of the world's earliest known republics and had existed in the region since before the birth of Mahavira (c. 599 BC).[9][10] The classical Gupta dynasty of Bihar presided over a period of cultural flourishing and learning, known today as the Golden Age of India.

The Pala Empire also made their capital at Pataliputra once during Devapala's rule. After the Pala period, Bihar came under the control of various kingdoms. The Karnat dynasty came into power in the Mithila region in the 11th century and they were succeeded by the Oiniwar dynasty in the 14th century. Aside from Mithila, there were other small kingdoms in medieval Bihar. The area around Bodh Gaya and much of Magadha came under the Buddhist Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya. The Khayaravala dynasty were present in the southwestern portions of the state until the 13th century.[11] For much of the 13th and 14th centuries, parts of Western Bihar were under the control of the Jaunpur Sultanate. These kingdoms were eventually supplanted by the Delhi Sultanate who in turn were replaced by the Sur Empire. After the fall of the Suri dynasty in 1556, Bihar came under the Mughal Empire and later was the staging post for the British colonial Bengal Presidency from the 1750s and up to the war of 1857–58. On 22 March 1912, Bihar was carved out as a separate province in the British Indian Empire. Since 1947 independence, Bihar has been an original state of the Indian Union.[12]

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

[edit]The earliest proof of human activity in Bihar is Mesolithic habitational remains at Munger.

Prehistoric rock paintings have been discovered in the hills of Kaimur, Nawada and Jamui. It was the first time that a Neolithic settlement was discovered in the thick of the alluvium, over the bank of the Ganges at Chirand.[13] The rock paintings depict a prehistoric lifestyle and natural environment. They depict the sun, the moon, stars, animals, plants, trees, and rivers, and it is speculated that they represent love for nature. The paintings also highlight the daily life of the early humans in Bihar, including activities like hunting, running, dancing and walking.[14] The rock paintings in Bihar are not only identical to those in central and southern India but are also akin to those in Europe and Africa. The rock paintings of Spain's Alta Mira and France's Lascaux are almost identical to those found in Bihar.[15]

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

[edit]Parallel to Indus Valley Civilization

[edit]In 2017 bricks dated to the mature Harappan period was discovered from the outskirts of the ancient city of Vaishali.[16][17] Any in-depth research which may establish definite links between Indus Valley Civilization and Bihar is yet to be conducted. A round seal excavated from Vaishali dated 200 BC-200 AD has three inscribed letters which according to Indus Valley Civilization scholar Iravatham Mahadevan represents formulas inscribed on the Indus seals and dates it to the earliest layers of excavation i-e 1100 BC.[18][19]

Rigvedic period

[edit]Kikata was an ancient kingdom in what is now India, mentioned in the Vedas. Some scholars have believed that they were the forefathers of Magadhas because Kikata is used as a synonym for Magadha in the later texts.[20] It probably lay to the south of Magadha Kingdom in a hilly landscape.[21] A section in the Rigveda (RV 3.53.14) refers to the Kīkaṭas (Hindi:कीकट), a tribe which most scholars have placed in present-day southwestern Bihar (Magadha) such as Weber and Zimmer[22] while some scholars such as Oldenburg and Hillebrandt dispute that. According to Puranic literature Kikata is placed near Gaya. It is described as extending from Caran-adri to Gridharakuta (vulture peak), Rajgir. Some scholar such as A. N. Chandra places Kikata in a hilly part of the Indus Valley based on the argument that countries between Magadh and the Indus Valley are not mentioned such as Kuru, Kosala etc. Kikatas were said to be Anarya or non-vedic people who didn't practice Vedic rituals like soma, According to Sayana, Kikatas didn't perform worship, were infidels and nastikas. The leader of Kikatas has been called Pramaganda, a usurer.[23][24] It is unclear whether Kikatas were already present in Magadh during the Rigvedic period or they migrated there later.[25] Like Rigveda attributes of Kikatas, Atharvaveda also speaks about southeastern tribes like Magadhas and Angas as hostile tribe who lived on the borders of Brahmanical India.[26] Bhagvata Purana mentions about the birth of Buddha among Kikatas.[27]

Some scholars have placed the Kīkaṭa kingdom, mentioned in the Rigveda, in Bihar (Magadha) because Kikata is used as a synonym for Magadha in the later texts;[22] however, according to Michael Witzel, Kīkaṭa was situated south of Kurukshetra in eastern Rajasthan or western Madhya Pradesh.[28] The placement in Bihar is also challenged by historical geographers Mithila Sharan Pandey (who argues they must have been near Western Uttar Pradesh),[29] and O.P. Bharadwaj (who places them near the Sarasvati River),[30] and historian Ram Sharan Sharma, who believes they were probably in Haryana.[31]

Northern black polished ware

[edit]Urbanization in the Gangetic plains began with the appearance of Northern black polished ware period and archaeologists trace the origin of this pottery in Magadh region of Bihar. The oldest dated site of NBWP is in Juafardih, Nalanda, which is carbon dated to 1200 BC.[32]

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

[edit]

Late Vedic Kingdoms

[edit]Videha (Mithila) Kingdom

[edit]Videha is mentioned in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as comprising parts of Bihar and extending into small parts of Nepal. The Hindu goddess Sita is described as the princess of Videha, daughter of Raja Janak. The capital of Videha is believed to be either Janakpur (in Present-day Nepal),[33] or Baliraajgadh (in Present-day Madhubani district, Bihar, India).[34][35]

Anga Kingdom

[edit]Some sources say that Anga tribe was not Vedic, it was captured by the Vedic Aryans and according to some legends, Anga was the first Vedic king of Anga kingdom which justifies the naming of the kingdom. The Anga tribe is believed to have been very powerful in the early vedic period. However, with the emergence of the kingdom of Magadha and Vaishali, Anga lost its importance. Karna, a friend of Duryodhana, was the king of Anga.

Magadha Kingdom

[edit]

The Magadha was established by a semi-mythical king Jarasandha, who the Puranas state was a king of the Brihadrathas dynasty and one of the descendants of King Puru. Jarasandha appears in the Mahabharatha as the "Magadhan Emperor who rules all India" and meets with an unceremonious ending. Jarasandha was the greatest among them during epic times. His capital, Rajagriha or Rajgir, is now a modern hill resort in Bihar. Jarasandha's continuous assault on the Yadava kingdom of Surasena resulted in their withdrawal from central India to western India. Jarasandha was a threat not only to the Yadavas but also to the Kurus. Pandava Bhima killed him in a mace dual aided by the intelligence of Vasudeva Krishna.

Thus, Yudhishthira, the Pandava King, could complete his campaign of bringing the whole of India into his empire. Jarasandha had friendly relations with Chedi king Shishupala, Kuru king Duryodhana and Anga king Karna. His descendants, according to the Vayu Purana, ruled Magadha for 1000 years followed by the Pradyota dynasty, which ruled for 138 years from 799 to 684 BC[contradictory]. However, there is insufficient evidence to prove the historicity of this claim. These rulers are nonetheless mentioned in the Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain texts. Palaka, the son of the Avanti king Pradyota, conquered Kaushambi, increasing the kingdom's power.

Mahajanapadas

[edit]

|

|

|

|

In the later Vedic Age, a number of small kingdoms or city-states, dominated Magadha. Many of these states have been mentioned in Buddhist and Jaina literature as far back as 1000 BC. By 500 BC, sixteen monarchies and 'republics' known as the Mahajanapadas – Kasi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajji (or Vriji), Malla, Chedi, Vatsa (or Vamsa), Kuru, Panchala, Matsya (or Maccha), Surasena, Assaka, Avanti, Gandhara and Kamboja – stretched across the Indo-Gangetic plains from modern-day Afghanistan to Bengal and Maharashtra. Vajji covered the modern North Bihar, Magadha covered South-western Bihar while Anga covered South-eastern Bihar. Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced to four major ones by 500/400 BC, that is by the time of Siddhartha Gautama. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala and Magadha.[36] In 537 BC, Siddhartha Gautama attained the state of enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, Bihar. Around the same time, Mahavira who was born in a place called Kundalagrama in the ancient kingdom of Kundalpur in [vaishli] in modern-day Bihar. He was the 24th Jain Tirthankara, propagated a similar theology, that was to later become Jainism.[37] However, Jain orthodoxy believes it predates all known time. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Jain Tirthankaras and an ascetic order similar to the sramana movement.[38] The Buddha's teachings and Jainism had doctrines inclined toward asceticism and were preached in Prakrit, which helped them gain acceptance amongst the masses. They have profoundly influenced practices that Hinduism and Indian spiritual orders are associated with namely, vegetarianism, prohibition of animal slaughter and ahimsa (non-violence).

While the geographic impact of Jainism was limited to India, Buddhist nuns and monks eventually spread the teachings of Buddha to Central Asia, East Asia, Tibet, Sri Lanka and South East Asia. Nalanda University and Vikramshila University one of the oldest residential universities were established in Bihar during this period.

Early Magadha Empire

[edit]According to both Buddhist texts and Jain texts, one of Pradyota tradition was that the King's son would kill his father to become the successor. During this time, it was reported that there were high crimes in Magadha. The people rose up and elected Shishunaga to become the new king, who destroyed the power of the Pradyotas and created the Shishunaga dynasty. Shishunaga (also called King Sisunaka) was the founder of a dynasty collectively called the Shishunaga dynasty. He established the Magadha empire (in 684 BC). Due in part to this bloody dynastic feuding, it is thought that a civil revolt led to the emergence of the Shishunaga dynasty. This empire, with its original capital in Rajgriha, later shifted to Pataliputra (both currently in the Indian state of Bihar). The Shishunaga dynasty was one of the largest empires of the Indian subcontinent.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Hariyanka dynasty king Bimbisara was responsible for expanding the boundaries of his kingdom through matrimonial alliances and conquest. The land of Kosala fell to Magadha in this way. Estimates place the territory ruled by this early dynasty at 300 leagues in diameter and encompassing 80,000 small settlements. Bimbisara is contemporary with the Buddha, and is recorded as a lay disciple. Bimbisara (543–493 BC) was imprisoned and killed by his son who became his successor, Ajatashatru (491–461 BC), under whose rule, the dynasty reached its largest extent.

Licchavi was an ancient—before the birth of Mahavira— republic in what is now the Bihar state of India.[10] Vaishali was the capital of Licchavi and the Vajjika League. The Mahavamsa tells that a courtesan in that city, Ambapali, was famous for her beauty, and helped in large measure in making the city prosperous.[42]

Ajatashatru went to war with the Licchavi several times. Ajatashatru is thought to have ruled from 551 BC to 519 BC and moved the capital of the Magadha kingdom from Rajagriha to Pataliputra. The Mahavamsa tells that Udayabhadra eventually succeeded his father, Ajatashatru, and that under him Pataliputra became the largest city in the world. He is thought to have ruled for sixteen years. The kingdom had a particularly bloody succession. Anuruddha eventually succeeded Udaybhadra through assassination, and his son Munda succeeded him in the same fashion, as his son Nagadasaka.

This dynasty lasted until 424 BC when it was overthrown by the Nanda dynasty. This period saw the development in Magadha of two of India's major religions. Gautama Buddha in the 6th or 5th century BC was the founder of Buddhism, which later spread to East Asia and Southeast Asia, while Mahavira revived and propagated the ancient sramanic religion of Jainism.

The Nanda dynasty was established by an illegitimate son of King Mahanandin from the previous Shishunaga dynasty. The Nanda dynasty ruled Magadha during the 5th and 4th centuries BC. At its greatest extent, the Nanda Empire extended from Burma in the east, Balochistan in the west and probably as far south as Karnataka.[43] Mahapadma Nanda of the Nanda dynasty, has been described as the destroyer of all the Kshatriyas. He defeated the Ikshvaku dynasty, as well as the Panchalas, Kasis, Haihayas, Kalingas, Asmakas, Kurus, Maithilas, Surasenas and the Vitihotras. He expanded his territory to the south of Deccan. Mahapadma Nanda died at the age of 88 and, therefore, he ruled during most of the period of this dynasty, which lasted 100 years.

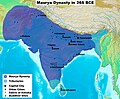

In 321 BC, exiled general Chandragupta Maurya, with the help of Chanakya, founded the Maurya dynasty after overthrowing the reigning Nanda king Dhana Nanda to establish the Maurya Empire. The Maurya Empire (322–185 BC), ruled by the Mauryan dynasty, was geographically extensive, powerful and a political-military empire in ancient India. During this time, most of the subcontinent was united under a single government for the first time. The exceptions were present-day Tamil Nadu and Kerala (which was a Tamil kingdom at that time). The empire had its capital city at Pataliputra (near modern Patna). The Mauryan empire under Chandragupta Maurya would not only conquer most of the Indian subcontinent, defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander the Great but also push its boundaries into Persia and Central Asia, conquering the Gandhara region. Chandragupta Maurya then defeated an invasion led by Seleucus I, a Greek general from Alexander's army. Chandragupta Maurya's minister, Kautilya Chanakya, wrote the Arthashastra, a treatise on economics, politics, foreign affairs, administration, military arts, war and religion.

Chandragupta Maurya was succeeded by his son, Bindusara, who expanded the kingdom over most of present-day India, other than the extreme south and east. At its greatest extent, the Empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the Himalayas, and to the east stretching into what is now Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan, annexing Balochistan and much of what is now Afghanistan. The Empire was extended into India's central and southern regions by the emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara, but it excluded the republic of Kalinga.

The Maurya Empire was inherited by Bindusara's son, Ashoka. Ashoka initially sought to expand his kingdom but in the aftermath of the carnage caused during the invasion of Kalinga, he renounced bloodshed and pursued a policy of non-violence or ahimsa after converting to Buddhism. Following the conquest of Kalinga, Ashoka ended the military expansion of the empire and led the empire through more than 40 years of relative peace, harmony and prosperity. Ashoka's response to the Kalinga War is recorded in the Edicts of Ashoka,[44] one of the oldest preserved historical documents of the Indian subcontinent.[45][46][47]

According to Rock Edicts of Ashoka:

"Beloved-of-the-Gods [Ashoka], King Priyadarsi, conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. 150000 were deported, 100000 were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dhamma, a love for the Dhamma and instruction in Dhamma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas."

— Ashoka, S. Dhammika, The Edicts of King Ashoka, Kandy, Buddhist Publications Society (1994) ISBN 955-24-0104-6

The Mauryan Empire under Ashoka was responsible for the proliferation of Buddhist ideals across the whole of East Asia and South-East Asia. Under Ashoka, India was a prosperous and stable empire of great economic and military power whose political influence and trade extended across Asia and into Europe. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka embraced Buddhism. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into Sri Lanka and South-East Asia. The Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath, is the emblem of India. Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Arthashastra, the Edicts of Ashoka and Ashokavadana are primary sources of written records of the Mauryan times.

Ashoka was followed for 50 years by a succession of weaker kings. Brihadrata, the last ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, held territories that had shrunk considerably from the time of emperor Ashoka, although he still upheld the Buddhist faith.

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – 1206 AD)

[edit]Middle Kingdom

Shunga Dynasty

[edit]The Shunga dynasty was established in 185 BC, about fifty years after Ashoka's death, when the king Brihadratha, the last of the Mauryan rulers, was assassinated by the then commander-in-chief of the Mauryan armed forces, Pushyamitra Shunga.

Pushyamitra Shunga was a Brahmin who then took over the throne and established the Shunga dynasty. Buddhist records such as the Ashokavadana write that the assassination of Brihadrata and the rise of the Shunga empire led to a wave of persecution of Buddhists,[49] and a resurgence of Hinduism. According to John Marshall,[50] Pushyamitra Shunga may have been the main author of the persecutions, although later Shunga kings seem to have been more supportive of Buddhism. Other historians, such as Etienne Lamotte[51] and Romila Thapar,[52] partially support this view.

Gupta Dynasty

[edit]The Gupta dynasty ruled from around 240 to 550 AD. The origins of the Gupta Dynasty are shrouded in obscurity. The Chinese traveller Xuanzang provides the first evidence of the Gupta kingdom in Magadha. He came to India in 672 AD and heard of 'Maharaja Sri-Gupta' who built a temple for Chinese pilgrims near Mrigasikhavana. Ghatotkacha (c. 280–319) AD, had a son named Chandra Gupta I (Not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya (340–293 BC), founder of the Mauryan Empire). In a breakthrough deal, Chandra Gupta I was married to a woman from Lichchhavi—the main power in Magadha.

Samudragupta succeeded Chandra Gupta I in 335, and ruled for about 45 years, until he died in 380. He attacked the kingdoms of Shichchhatra, Padmavati, Malwas, the Yaudheyas, the Arjunayanas, the Maduras and the Abhiras, and merged them in his kingdom. By his death in 380, he had incorporated over twenty kingdoms into his realm, his rule extended from the Himalayas to the river Narmada and from the Brahmaputra to the Yamuna. He gave himself the titles King of Kings and World Monarch. He is considered the Napoleon of India. Chandra Gupta I performed Ashwamedha Yajna to underline the importance of his conquest.

Chandra Gupta II, the Sun of Power (Vikramaditya), ruled from 380 until 413. Only marginally less successful than his father, Chandra Gupta II expanded his realm westwards, defeating the Saka Western Kshatrapas of Malwa, Gujarat and Saurashtra in a campaign lasting until 409. Chandragupta II was succeeded by his son Kumaragupta I. Known as the Mahendraditya, he ruled until 455. Towards the end of his reign a tribe in the Narmada valley, the Pushyamitras, rose in power to threaten the empire.

Skandagupta is generally considered the last of the great rulers.[53] He defeated the Pushyamitra threat, but then was faced with invading Hephthalites or Huna, from the northwest. He repulsed a Huna attack c. 477. Skandagupta died in 487 and was succeeded by his son Narasimhagupta Baladitya.

The Gupta Empire was one of the largest political and military empires in ancient India. The Gupta period is referred to as the Classical Age of India by most historians. The time of the Gupta Empire was an "Indian Golden Age" in Indian science, technology, engineering, art, dialectic, literature, logic, mathematics, astronomy, religion and philosophy.[54]

The Gupta Empire had their capital at Pataliputra. The difference between the Gupta Empire's and Mauryan Empire's administration was that in the Mauryan administration power was centralised but in the Gupta administration power was more decentralised. The empire was divided into provinces and the provinces were further divided into districts. Villages were the smallest units. The kingdom covered Gujarat, North-East India, south-eastern Pakistan, Odisha, northern Madhya Pradesh and eastern India with capital at Pataliputra, modern Patna. All forms of worship were carried out in Sanskrit.

Rapid strides were made in astronomy during this period. Aryabhata and Varahamihira were two great astronomers and mathematicians. Aryabhata stated that the earth moved around the sun and rotated on its axis. Aryabhata, who is believed to be the first to come up with the concept of zero, postulated the theory that the Earth moves round the Sun, and studied solar and lunar eclipses. Aryabhata's most famous work was Aryabhatiya. Varahamihira's most important contributions are the encyclopaedic Brihat-Samhita and Pancha-Siddhantika (Pañcasiddhāntikā). Metallurgy also made rapid strides. The proof can be seen in the Iron Pillar of Vaishali[55] and near Mehrauli on the outskirts of Delhi, which was brought from Bihar.[56]

This period is also very rich in Sanskrit literature. The material sources of this age were Kalidasa's works. Raghuvamsa, Malavikagnimitram, Meghadūta, Abhijñānaśākuntala and Kumārasambhava, Mṛcchakatika by Shudraka, Panchatantra by Vishnu Sharma, Kama Sutra (the principles of pleasure) and 13 plays by Bhasa were also written in this period.

In medicine, the Guptas were notable for their establishment and patronage of free hospitals. Although progress in physiology and biology was hindered by religious injunctions against contact with dead bodies, which discouraged dissection and anatomy, Indian physicians excelled in pharmacopoeia, caesarean section, bone setting, and skin grafting. Indeed, Hindu medical advances were soon adopted in the Arab and Western worlds. Ayurveda was the main medical system.

According to some historian's work,

The Gupta Empire is considered by many scholars to be the "classical age" of Hindu and Buddhist art and literature. The Rulers of the Gupta Empire were strong supporters of developments in the arts, architecture, science, and literature. The Gupta Empire circulated a large number of gold coins, called dinars, with their inscriptions. The Gupta Dynasty also left behind an effective administrative system. During times of peace, the Gupta Empire system was decentralised, with only taxation flowing to the capital at Pataliputra. During times of war, however, the government realigned and fought its invaders. The system was soon extinguished in fighting off the Hunnic Invasions.[57][58]

Later Gupta dynasty

[edit]

The Later Gupta dynasty ruled the Magadha region in eastern India between the 6th and 7th centuries AD. The Later Guptas succeeded the imperial Guptas as the rulers of Magadha, but there is no evidence connecting the two dynasties; these appear to be two distinct families.[59] The Later Guptas are so-called because the names of their rulers ended with the suffix "-gupta", which they might have adopted to portray themselves as the legitimate successors of the imperial Guptas.[60]

Pala Dynasty

[edit]The Pala Empire was a Buddhist dynasty that ruled from the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent. The name Pala (Modern Bengali: পাল pal) means protector and was used as an ending to the names of all Pala monarchs. The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism. Gopala was the first ruler of the dynasty. He came to power in 750 in Gaur by a democratic election. This event is recognised as one of the first democratic elections in South Asia since the time of the Mahā Janapadas. He reigned from 750 to 770 and consolidated his position by extending his control over all of Bengal as well as parts of Bihar. The Buddhist dynasty lasted for four centuries (750–1120 CE).

The empire reached its peak under Dharmapala and Devapala. Dharmapala extended the empire into the northern parts of the Indian Subcontinent. This triggered once again the power struggle for the control of the subcontinent. Devapala, successor of Dharmapala, expanded the empire to cover much of South Asia and beyond. His empire stretched from Assam and Utkala in the east, Kamboja (modern-day Afghanistan) in the north-west and Deccan in the south. According to Pala copperplate inscription, Devapala exterminated the Utkalas, conquered the Pragjyotisha (Assam), shattered the pride of the Huna, and humbled the lords of Gurjara-Pratiharas, Gurjara and the Dravidas.

The Palas created many temples and works of art as well as supported the Universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila. Both Nalanda University and Vikramshila University reached their peak under the Palas. The universities received an influx of students from many parts of the world. Bihar and Bengal were invaded by the south Indian Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty in the 11th century.[61][62] The Pala Empire eventually disintegrated in the 12th century under the attack of the Sena dynasty. Pala Empire was the last empire of middle kingdoms whose capital was once in Pataliputra (modern Patna) under Devapala's rule.

Medieval Period (1206–1526)

[edit]

|

|

During the medieval period, Bihar was controlled by various small kingdoms and principalities. Bihar also experienced its first encounter with foreign aggression from the West and Muslim armies came to approach its border.[64] With the advent of foreign aggression and eventual foreign subjugation of India, Bihar passed through very uncertain times during the medieval period. Muhammad of Ghor attacked this region of the Indian subcontinent many times. Muhammad of Ghor's armies destroyed many Buddhist structures, including the great Nalanda University.[65][11]

The Buddhism of Magadha was finally swept away by the Islamic invasion under Muhammad Bin Bakhtiar Khilji, one of Qutb-ud-Din's generals destroyed monasteries fortified by the Sena armies, during which many of the viharas and the famed universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila were destroyed, and thousands of Buddhist monks were massacred in the 12th century.[66][67][68][69][70][11]

However, North Bihar/Mithila maintained its autonomy for longer than the rest of Bihar and was under the control of native dynasties until at least the sixteenth century.

Mithila

[edit]Karnat dynasty (1097-1324)

[edit]

In 1097 AD, the Karnat dynasty of Mithila emerged on the Bihar/Nepal border area and maintained capitals in Darbhanga and Simraongadh. The dynasty was established by Nanyadeva, a military commander of Karnataka origin. Under this dynasty, the Maithili language started to develop with the first piece of Maithili literature, the Varna Ratnakara being produced in the 14th century by Jyotirishwar Thakur. The Karnats also carried out raids into Nepal. They fell in 1324 following the invasion of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq.[71][11]

Oiniwar dynasty (1325-1526)

[edit]The Oiniwar dynasty emerged after the fall of the Karnats and ruled North Bihar as vassals of the Delhi Sultanate. Under the king, Shiva Singh, they did attempt to revolt against the throne in Delhi although this was eventually defeated. They were contemporaries of the Jaunpur Sultanate.[72]

Rest of Bihar

[edit]Pithipatis (1120-1290)

[edit]During the late Pala period, the area of Magadha was ruled by Buddhist kings with the title of Pīṭhīpati. They were patrons of the Mahabodhi temple and referred to themselves as magadhādipati (rulers of Magadha). They maintained a presence in the region until at least the 13th century.[73][11]

Cheros

[edit]After the fall of the Pala empire, the Cheros established a tribal polity that ruled some parts of southern Bihar extending into modern-day Jharkhand from the 12th century to the 16th century until Mughal rule after which they were reduced to chieftains/Zamindars.[74]

Khayaravala dynasty (11th-13th centuries)

[edit]The Khayaravalas were the ruling dynasty of the Son river valley in South Bihar and Jharkhand during the 11th to 13th centuries. Notable kings of this dynasty include Pratapdhavala and Shri Pratapa. They were also involved in the construction of Rohtasgarh fort.[75]

Jaunpur Sultanate (1394–1493)

[edit]The Jaunpur Sultanate emerged in 1394 and controlled much of Western Bihar. Many coin hoards and inscriptions from the Jaunpur period have been found in Bihar.[76]

Early modern period (1526–1757)

[edit]Sur Empire

[edit]Medieval Bihar saw a period of glory lasting about six years during the rule of Sher Shah Suri, who hailed from Sasaram. Sher Shah Suri built the longest road of the Indian subcontinent, the Grand Trunk Road, which started at Calcutta (Bengal) and ended at Peshawar, now Pakistan. The economic reforms carried out by Sher Shah, such as the introduction of the Rupee and Custom Duties, are still used in the Republic of India. He revived the city of Patna, where he built his headquarters.[77][78]

Hemu, the Hindu Emperor, the son of a food seller, and himself a vendor of saltpetre at Rewari,[79] rose to become Chief of Army and Prime Minister[80][81] under the command of Adil Shah Suri of the Suri Dynasty. He had won 22 battles against the Afghans, from Punjab to Bengal and had defeated Akbar's forces twice, at Agra and Delhi in 1556,[82] before succeeding to the throne of Delhi and establishing a 'Hindu Raj' in North India, albeit for a short duration, from Purana Quila in Delhi. He was killed in the Second Battle of Panipat.

Zamindars of Bihar and the Mughals

[edit]During the period of Islamic rule, much of Bihar was under the sway of local Zamindars or chieftains who maintained their armies and territories. These chieftains retained much of their power until the arrival of the British East India Company.[83]

In 1576, after the Battle of Tukaroi, Mughal Emperor Akbar conquered Bengal Sultanate and added it to his empire domain. He divided Bihar and Bengal each into one of his original twelve subahs (imperial top-level provinces; Bihar Subah with its seat at Patna) and the region passed through uneventful provincial rule during much of this period. Bihar was left under Mughal control until the Battle of Plassey in 1757.[84]

Bihar passed into the control of Nawabs of Bengal under British suzerainty.

Prince Azim-us-Shan, the grandson of Aurangzeb was appointed as the governor of Bihar in 1703.[85] Azim-us-Shan renamed Pataliputra or Patna as Azimabad, in 1704.[86][87]

Colonial Period (1757–1947)

[edit]British East India Company

[edit]After the Battle of Buxar, 1764, which was fought in Buxar, hardly 115 km from Patna, the Mughals as well as the Nawabs of Bengal lost effective control over the territories then constituting the province of Bengal, which currently comprises Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha. The British East India Company was accorded the diwani rights, that is, the right to administer the collection and management of revenues of the province of Bengal, and parts of Oudh, currently comprising a large part of Uttar Pradesh. The Diwani rights were legally granted by Shah Alam, who was then the sovereign Mughal emperor of India. During the rule of the British East India Company in Bihar, Patna emerged as one of the most important commercial and trading centres of eastern India, preceded only by Kolkata.

The first seeds of resentment against British rule emerged when Maharaja Fateh Bahadur Sahi, the chieftain of Huseypur in Saran district, initiated a struggle against the East India Company in 1767. His revolt escalated in 1781 when various other zamindars and chiefs in South Bihar began to join his revolt including Raja Narain Singh and Akbar Ali.[88] The British were able to successfully put down the revolt.

Babu Kunwar Singh of Jagdishpur and his army, as well as countless other persons from Bihar, contributed to the India's First War of Independence (1857), also called the Sepoy Mutiny by some historians. Babu Kunwar Singh (1777–1858) one of the leaders of the Indian uprising of 1857 belonged[89] to a royal Rajput house of Jagdispur, currently a part of Bhojpur district of Bihar. By that time Bihar had many feudal estates or zamindars. Most notably Tekari Raj, Raj Darbhanga, Bettiah Raj, Hathwa Raj, Kharagpur Raj and Banaili Estate. At the age of 80 years, during India's First War of Independence, he actively led a select band of armed soldiers against the troops under the command of the East India Company and also recorded victories in many battles.[90]

from 1776

(1912-1936)

The British Raj

[edit]Under the British Raj, Bihar particularly Patna gradually started to attain its lost glory and emerged as an important and strategic centre of learning and trade in India. From this point, Bihar remained a part of the Bengal Presidency of the British Raj until 1912, when the province of Bihar and Orissa was carved out as a separate province. When the Bengal Presidency was partitioned in 1912 to carve out a separate province, Patna was made the capital of the new province. The city limits were stretched westwards to accommodate the administrative base, and the township of Bankipore took shape along the Bailey Road (originally spelt as Bayley Road, after the first Lt. Governor, Charles Stuart Bayley). This area was called the New Capital Area. The houses of the English residents were all at the west end at Bankipore. The greater part of the English residences were on the banks of the river, many of them being on the northern side of an open square, which formed the parade ground, and racecourse (present Gandhi Maidan). There was also the Golghar a wondrous bell-shaped building, one hundred feet high, with a winding outer staircase leading to the top, and a small entrance door at the base, which was intended for a granary, to be filled when there was the expectation of famine. It was initially considered to be both politically and materially impracticable.

To this day, locals call the old area the City whereas the new area is called the New Capital Area. The Patna Secretariat with its imposing clock tower and the Patna High Court are two imposing landmarks of this era of development. Credit for designing the massive and majestic buildings of colonial Patna goes to the architect, I. F. Munnings. By 1916–1917, most of the buildings were ready for occupation. These buildings reflect either Indo-Saracenic influence (like Patna Museum and the state Assembly), or overt Renaissance influence like the Raj Bhawan and the High Court. Some buildings, like the General Post Office (GPO) and the Old Secretariat, bear pseudo-Renaissance influence. Some say the experience gained in building the new capital area of Patna proved very useful in building the imperial capital of New Delhi.

The British built several educational institutions in Patna like Patna College, Patna Science College, Bihar College of Engineering, Prince of Wales Medical College and the Bihar Veterinary College. With government patronage, the Biharis quickly seized the opportunity to make these centres flourish quickly and attain renown. In 1935, certain portions of Bihar were reorganised into the separate province of Orissa. Patna continued as the capital of Bihar province under the British Raj.

Independence movement

[edit]

Bihar played a major role in the Indian independence struggle. Most notable were the Champaran movement against the Indigo plantation and the Quit India Movement of 1942. Leaders like Chandradeo Prasad Verma,[91] Ajit Kumar Mehta,[92] Swami Sahajanand Saraswati,[93] Shaheed Baikuntha Shukla, Sri Krishna Sinha, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Mulana Mazharul Haque, Loknayak Jayaprakash Narayan, Basawon Singh (Sinha), Yogendra Shukla, Sheel Bhadra Yajee, Pandit Yamuna Karjee, Dr. Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi and many others who worked for India's independence and worked to lift up the underprivileged masses. Khudiram Bose, Upendra Narayan Jha "Azad" and Prafulla Chaki were also active in revolutionary movement in Bihar.

After his return from South Africa, it was from Bihar that Mahatma Gandhi launched his pioneering civil-disobedience movement, Champaran Satyagraha.[94] Raj Kumar Shukla drew Mahatma Gandhi's attention to the exploitation of the peasants by the European indigo planters. Champaran Satyagraha received the spontaneous support from many Biharis, including Brajkishore Prasad, Rajendra Prasad (who became the first President of India) and Anugrah Narayan Sinha (who became the first Deputy Chief Minister and Finance Minister of Bihar).[95]

In India's struggle for independence, the Champaran Satyagraha marks a very important stage. Raj Kumar Shukla drew the attention of Mahatma Gandhi, who had just returned from South Africa, to the plight of the peasants suffering under an oppressive system established by European indigo planters. Besides other excesses, they were forced to cultivate indigo on 3/20 part of their holding and sell it to the planters at prices fixed by the planters. This marked Gandhi's entry into India's independence movement. On arrival at the district headquarters in Motihari, Gandhi and his team of lawyers—Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Dr. Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Brajkishore Prasad and Ram Navami Prasad, whom he had handpicked to participate in the satyagraha—were ordered to leave by the next available train. They refused to do this, and Gandhi was arrested. He was released and the ban order was withdrawn in the face of a "Satyagraha" threat. Gandhi conducted an open inquiry into the peasant's grievances. The Government had to appoint an inquiry committee with Gandhi as a member. This led to the abolition of the system.

Raj Kumar Shukla has been described by Gandhi in his Atmakatha, as a man whose suffering gave him the strength to rise against the odds. In his letter to Gandhi he wrote "Respected Mahatma, You hear the stories of others everyday. Today please listen to my story.... I want to draw your attention to the promise made by you in the Lucknow Congress that you would come to Champaran. The time has come for you to fulfill your promise. 1.9 million suffering people of Champaran are waiting to see you."

Gandhi reached Patna on 10 April 1917 and on 16 April he reached Motihari accompanied by Raj Kumar Shukla. Under Gandhi's leadership the historic "Champaran Satyagraha" began. The contribution of Raj Kumar Shukla is reflected in the writings of Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Acharya Kriplani and Mahatma Gandhi. Raj Kumar Shukla maintained a diary in which he gave an account of his struggle against the atrocities of the indigo planters, atrocities so movingly depicted by Dinabandhu Mitra in Nil Darpan, a play that was translated by Michael Madhusudan Dutt. This movement by Mahatma Gandhi received the spontaneous support of a cross-section of people, including Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Bihar Kesari Sri Krishna Sinha, Dr. Anugrah Narayan Sinha and Brajkishore Prasad.

Shaheed Baikuntha Shukla was another nationalist from Bihar, who was hanged for murdering a government approver named Phanindrananth Ghosh. This led to the hanging of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru. Phanindranath Ghosh hitherto a key member of the Revolutionary Party had betrayed the cause by turning an approver and giving evidence, which led to his murder. Baikunth was commissioned to plan the murder of Ghosh. He carried out the killing successfully on 9 November 1932. He was arrested, tried, and convicted, and, on 14 May 1934, he was hanged in Gaya Central Jail. Karpoori Thakur also played an important role in the freedom struggle.[96]

In North and Central Bihar, a peasant movement was an important side effect of the independence movement. The Kisan Sabha movement started in Bihar under the leadership of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati who in 1929 had formed the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha (BPKS) to mobilise peasant grievances against the zamindari attacks their occupancy rights.[97] Gradually the peasant movement intensified and spread across the rest of India. All these radical developments on the peasant front culminated in the formation of the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) at the Lucknow session of the Indian National Congress in April 1936, with Swami Sahajanand Saraswati elected as its first President.[98] This movement aimed at overthrowing the feudal zamindari system instituted by the British. It was led by Swami Sahajanand Saraswati and his followers Pandit Yamuna Karjee, Rahul Sankrityayan and others. Pandit Yamuna Karjee along with Rahul Sankrityayan and other Hindi literary figures started publishing a Hindi weekly Hunkar from Bihar in 1940. Hunkar later became the mouthpiece of the peasant movement and the agrarian movement in Bihar and was instrumental in spreading the movement. The peasant movement later spread to other parts of the country and helped in digging out the British roots in the Indian society by overthrowing the zamindari system.

During the Quit India movement, in Saran district of Bihar, Chandrama Mahto received bullet injuries during a protest against the colonial authorities and was subsequently martyred on the same day. In Shahabad district, Maharaj Koeri was wounded in police firing at Behea. Ramjas Koeri was arrested, and taken into confinement, he died in prison, presumably due to brutal assault by Police.[99] Noted revolutionary Chandradeo Prasad Verma was also arrested during Quit India movement, he underwent rigorous imprisonment for two years from 1943 to 1945. After his release from imprisonment, he restarted revolutionary activities once again and plotted a conspiracy to blast Bikram Airport in Patna.[91] In Khagaria district, Prabhu Narayan was shot by the colonial police white attempting to unfurl Indian flag during Quit India movement.[100]

Towards the end of 1946, between 30 October and 7 November, a massacre of Muslims in Bihar made Partition more likely. Begun as a reprisal for the Noakhali riot, it was difficult for authorities to deal with because it was spread out over a large number of scattered villages, and the number of casualties was impossible to establish accurately: "According to a subsequent statement in the British Parliament, the death-toll amounted to 5,000. The Statesman's estimate was between 7,500 and 10,000; the Congress party admitted to 2,000; Mr. Jinnah claimed about 30,000."[101]

The first Cabinet of Bihar was formed on 2 April 1946, consisting of two members, Dr. Sri Krishna Sinha as the first Chief Minister of Bihar and Dr. Anugrah Narayan Sinha as Deputy Chief Minister and Finance Minister of Bihar (also in charge of Labour, Health, Agriculture and Irrigation).[102][103][104] Other ministers were inducted later. The Cabinet served as the first Bihar Government after independence in 1947. In 1950, Dr. Rajendra Prasad from Bihar became the first President of India.

Post-Independence (1947–1990)

[edit]The Indian National Congress dominated the state for much of the decades after independence except for a brief period in the 1960s and 70s when some of the backward caste leaders were successful in forming a non-Congress government in the state.[105][106] Satish Prasad Singh was the first OBC chief minister of the state for a very brief period, who succeeded Mahamaya Prasad Sinha.[107] In the later period, the upper-caste remained active in politics but the backward caste were gradually becoming vocal in political space. The lead was taken by Upper Backward Castes, who were the biggest beneficiaries of the land reform drive undertaken in the early decades of independence and were now becoming active in the politics of the state. A section of these upper-backwards also emulated the practices of erstwhile Zamindars and committed atrocities against the Dalits. The Naxalite uprising in the state also forced the upper caste to sell off their most vulnerable holdings, which were most often bought by the peasants of these upper backward communities.[108][109] The naxal uprising in the state led to foundation of several caste-based private armies which perpetrated massacres of lower caste people on the charge of being the supporters of the Naxalites. Ranvir Sena, Bhumi Sena and Kuer Sena were some of the most dreaded caste armies.[110] The Bhojpur region remained the hotspot of the Naxalite movement in the Bihar, where Master Jagdish lead the uprising against the landlords.[111] Some of the biggest massacres took place during this period in which both upper-caste and the Dalits remained the victims. The Upper Backward Castes were in two front confrontations with both the Dalits as well as upper castes.[112][113]

The caste wars coincided with the rise of backward caste politics against upper-caste domination in Bihar and throughout North India after the implementation of the Mandal Commission report. The most numerous and powerful backward community were the Yadavs, and the 1990s saw the rise of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) led by Lalu Prasad Yadav. This party held the Yadav/Muslim vote bank, a combination also held by the Samajwadi party, its UP counterpart. This allowed the RJD to sweep to power throughout the 1990s. His platform was one of social justice, increasing reservations for lower castes. However critics of the era have claimed it was a 'Jungle raj.'[114][115]

Contemporary period

[edit]Lalu Prasad Yadav (1990–2005)

[edit]

In 1989, in the 9th General election to the Lok Sabha, the Janata Dal emerged as a serious challenge to the Indian National Congress party at the central level. The rise of Janata Dal also affected the state politics of Bihar which was dominated by the upper castes for long who were controlling the Congress firmly in the state, a charge disputed by some scholars. The Janata Dal was composed of three different wings which drew its strength from different classes of society. The first wing was under the leadership of Chandra Shekhar, who had reached out to the other Socialists and also to one splinter group under Morarji Desai. The second faction consisted of some of the old congressmen including Arun Nehru and former Defence Minister Vishwanath Pratap Singh. The third group drew its support from backward castes and middle peasantry, led by Charan Singh. Although Charan Singh was the leader of this faction, the actual leadership emerged after his death under the new generation of politicians like Lalu Prasad Yadav, who was a product of student politics of the 1970s.[116][105][106]

Yadav was appointed as the first OBC president of the Patna University student union in 1967. In 1974, he was appointed as the head of the Bihar student agitation committee which led the protest against the Congress-led government of the state during the Bihar Movement under the mentorship of Jay Prakash Narayan. According to Seyed Hossein Zarhani, throughout his leadership period at Patna University, his image was of a popular backward caste leader who fought against upper-caste dominance.[116]

In 1975, as an activist in the campaign against Indira Gandhi, he was arrested and after the end of National Emergency, he was elected as Member of Parliament in 1977 from Chhapra constituency on the ticket of Janata Party. In the 1980 and 1989 state assembly elections, Yadav was elected as Member of Legislative Assembly from Sonepur. He was the successor of Karpoori Thakur as the leader of opposition in Bihar Legislative Assembly who finally assumed the post of Chief Minister in 1990. Yadav's appointment as Chief Minister changed the socio-political profile of the state and in the coming years he emerged as the undisputed leader in Bihar who controlled the politics of the state earlier himself and later through his wife, Rabri Devi.[116]

Yadav followed the footsteps of his predecessors and Janta Dal under him indicated that it is the only party which is prepared to keep the backwards at the centre of the administration. Hence after assuming power, Lalu Yadav's government transferred 12 out of 13 Divisional Commissioners and 250 out of 324 Returning Officers in order to keep lower-caste people at the helm of all affairs at the local level. Many OBC bureaucrats were brought to the main departments from the sidelines and were given key positions such as the strategic posts of District Magistrates and Deputy Divisional Commissioners to the extent that they became least equivalent to the upper-castes. Three years after Yadav assumed power, many upper-caste officials attained transfer to the centre to avoid the alleged humiliation and ill-treatment they suffered in Bihar. The Panchayati Raj Bill and the Patna University and Bihar University amendment bill passed by the state legislature in 1993 also paved the way for the entry of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and OBCs in the state services in bulk.[117] According to Christophe Jaffrelot:

Lalu Prasad Yadav has deliberately introduced a new style of politics, highlighting the rustic qualities of low castes of Bihar. For instance, he makes the point of speaking the Bhojpuri dialect or English with a strong Bhojpuri accent, to the horror of the upper classes. He was also adept at confronting them. One of his early slogans was, Bhurabal Hatao, (wipe out Bhumihar, Brahmin, Rajput and Lala (Kayasth)). A few months after he became Chief Minister, he utilised his control of state media to describe the opposition to the Mandal as the conspiracy of the upper castes.[117]

Rise of Nitish Kumar (Post 1997)

[edit]"Ram Vilas Paswan was often seen with Mont Blanc pen, Cartier glasses and Rado prompting his critics to brand him a ‘five-star Dalit’. But in his pockets of influence in Bihar, his whirling helicopter was enough to make people chant, “Dharti Gunje Aasman, Ram Vilas Paswan.” Paswan was among the most popular faces when the social churn began in post-Emergency Bihar. In 1983, he formed the Dalit Sena, on the lines of the Schedule Caste Federation of BR Ambedkar."

The Janata Dal had survived the splits in past when leaders like George Fernandes and Nitish Kumar defected to form Samata Party in 1994, but it remained a baseless party after the decision of Yadav to form Rashtriya Janata Dal in 1997. The second split took place before the Rabri Devi assuming power which resulted in Janata Dal having only two leaders of any consequence in it, namely Sharad Yadav and Ram Vilas Paswan. Paswan was regarded as the rising leader of Dalits and had the credit of winning his elections with unprecedented margins. His popularity reached the national level when he was awarded the post of Minister of Railways in the United Front government in 1996 and was subsequently made the leader of Lok Sabha. His outreach was witnessed in the western Uttar Pradesh too, when his followers organised an impressive rally at the behest of a newly floated organisation called Dalit Panthers.[119] Sharad Yadav was also a veteran socialist leader but without any massive support base. In the 1998 Parliamentary elections, the Samata Party and Janata Dal, which was in a much weaker position after the formation of RJD ended up eating each other's vote base. This made Nitish Kumar merge both the parties to form Janata Dal (United).[120]

In 1999 Lok Sabha elections, Rashtriya Janata Dal received a setback at the hand of BJP+JD(U) combine. The new coalition emerged leading in 199 out of 324 assembly constituencies and it was widely believed that in the forthcoming election to Bihar state assembly elections, the Lalu-Rabri rule will come to an end. The RJD had fought the election in an alliance with the Congress but the coalition didn't work making state leadership of Congress believe that the maligned image of Lalu Prasad after his name was drawn in the Fodder Scam had eroded his support base. Consequently, the Congress decided to fight the 2000 assembly elections alone. The RJD had to be satiated with the communist parties as the coalition partners but the seat-sharing conundrum in the camp of NDA made Nitish Kumar pull his Samta Party out of the Sharad Yadav and Ram Vilas Paswan faction of the Janata Dal. Differences also arose between the BJP and Nitish Kumar who later wanted to be projected as the Chief Minister of Bihar but the former was not in favour. Even Paswan also wanted to be a CM face. The Muslims and OBCs were too divided in their opinion. A section of Muslims, which included the poor communities like Pasmanda were of the view that Lalu only strengthened upper Muslims like Shaikh, Sayyid and Pathans and they were in search of new options.[121]

Yadav also alienated other dominant backward castes like Koeri and Kurmi since his projection as the saviour of Muslims. It is argued by Sanjay Kumar that the belief that, "the dominant OBCs like the twin caste of Koeri-Kurmi will ask for share in power if he (Yadav) seeks their support while the Muslims will remain satisfied with the protection during communal riots only" made Yadav neglect them. Moreover, the divisions in both camps made the political atmosphere in the state a charged one in which many parties were fighting against each other with no visible frontiers. JD(U) and BJP were fighting against each other on some of the seats and so was the Samta Party. The result was a setback for the BJP, which in media campaigns was emerging with a massive victory. RJD emerged as the single largest party and with the political maneuvere of Lalu Yadav, Rabri Devi was sworn in as the Chief Minister again. The media largely failed to gauge the ground-level polarisation in Bihar.[121] According to Sanjay Kumar:

there can be no doubt about one thing that the upper-caste media was always anti Lalu and it was either not aware of the ground level polarisation in the Bihar, or deliberately ignored it. If the election result did not appear as a setback for RJD, it was largely because of the bleak picture painted by the media. Against this background, RJD's defeat had appeared like a victory.[121]

Even after serving imprisonment in connection with the 1997 scam, Lalu seemed to relish his role as a lower-caste jester. He argued that corruption charges against him and his family were the conspiracy of the upper-caste bureaucracy and media elites threatened by the rise of peasant cultivator castes. In 2004, Lalu's RJD had outperformed other state-based parties by winning 26 Lok Sabha seats in Bihar. He was awarded the post of Union Railway minister but the rising aspirations of the extremely backward castes unleashed by him resulted in JD(U) and BJP-led coalition to defeat his party in 2005 Bihar Assembly elections. Consequently, Nitish Kumar a leader of OBC Kurmi caste was sworn in as the chief minister. During Lalu's time backward caste candidates came to dominate the Bihar assembly claiming half of the seats in it and it was the aspiration of this powerful social community which led to friction among the united backwards, leading to the rise of Nitish Kumar who made both social justice and development as his political theme.[122]

Nitish Kumar (2005 onwards)

[edit]Thus, the 2005 Bihar assembly elections ended the 15 years of continuous RJD rule in the state, giving way to NDA led by Nitish Kumar. Bihari migrant workers have faced violence and prejudice in many parts of India, like Maharashtra, Punjab and Assam.[123][124][125]

To mark the separation of Bihar from Bengal on 22 March 1912, the completion of 100 years of existence is being celebrated in the name of Bihar Shatabadi Celebration Utsav.[126] There was a political crisis over post of the chief minister during February 2015.

Timeline for Bihar

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Pataliputra as a capital of the Kingdom of Magadha (6th–4th centuries BC).

-

Pataliputra as a capital of Maurya Empire.

The Maurya Empire at its largest extent under Ashoka the Great. -

Pataliputra as a capital of Shunga Empire.

Approximate greatest extent of the Shunga Empire (c. 185 BC). -

Pataliputra as a capital of Gupta Empire. Approximate greatest extent of the Gupta Empire.

-

Pataliputra as a capital of Pala Empire under Devapala's rule. Approximate extent of the Pala Empire in 800 AD.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Roy, Ramashray; Wallace, Paul (6 February 2007). India's 2004 Elections: Grass-Roots and National Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. 212. ISBN 9788132101109. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "BIHAR: A QUICK GUIDE TO SARAN". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Oldest hamlet faces extinction threat". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017.

- ^ Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, pages 13, 17 116-124, 141-143

- ^ Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, pages 13, 141-143

- ^ Raychaudhuri Hemchandra (1972), Political History of Ancient India, Calcutta: University of Calcutta, pp.85-6

- ^ Mishra Pankaj, The broblem, Seminar 450 - February 1997

- ^ "The History of Bihar". Bihar Government website. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Licchavi", Encyclopædia Britannica Online Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "", Encyclopædia Britannica Online Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Chakrabarty, Dilip (2010). The Geopolitical Orbits of Ancient India: The Geographical Frames of the Ancient Indian Dynasties. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-19-908832-4.

- ^ Gopal, S. (2017). Mapping Bihar: From Medieval to Modern Times. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ "Directorate of Archaeology - Page 1". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2015. Prehistoric era in Bihar

- ^ http://discoverbihar.bih.nic.in/pages/art_craft.htm#Rock%20Paintings Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Rock painting at Kaimur

- ^ "Kaimur Hills - Home to Prehistoric Tales". Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2008. discovery of rock paintings

- ^ "Harappan Civilization and Vaishali Bricks". ResearchGate. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Harappa signs in bricks of Raghopur". telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Mahadevan, Iravatham (March 1999). "Murukan in the Indus script" (PDF). Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies. XVI: 3–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ I. Mahadevan (1999)

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony; Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1995). Vedic Index of Names and Subjects. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 9788120813328.

- ^ Chandra, A. n (1980). The Rig Vedic Culture and the Indus Civilisation.

- ^ a b e.g. McDonell and Keith 1912, Vedic Index; Rahurkar, V.G. 1964. The Seers of the Rgveda. University of Poona. Poona; Talageri, Shrikant. (2000) The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis

- ^ Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, Their Religion and Institutions: Inquiry whether the Hindus are of Trans-Himalayan origin, and akin to the western branches of the Indo-European race. 2d ed., rev. 1871. Trübner. 1871.

- ^ Rig-Veda (1857). Rig-Veda Sanhitá a Collection of Ancient Hindú Hymns Translated from the Original Sanskrit by H.H. Wilson: Third and fourth ashtakas or books of the Rig-Veda. Wm. H. Allen and Company. p. 86.

kikata rigveda.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (15 April 2014). The Vedas: An Introduction to Hinduism's Sacred Texts. Penguin UK. ISBN 9788184757637.

- ^ Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, Their Religion and Institutions: Inquiry whether the Hindus are of Trans-Himalayan origin, and akin to the western branches of the Indo-European race. 2d ed., rev. 1871. Trübner. 1871.

- ^ Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, Their Religion and Institutions: Inquiry whether the Hindus are of Trans-Himalayan origin, and akin to the western branches of the Indo-European race. 2d ed., rev. 1871. Trübner. 1871.

- ^ M. Witzel. "Rigvedic history: poets, chieftains, and polities," in The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. ed. G. Erdosy (Walter de Gruyer, 1995), p. 333

- ^ Mithila Sharan Pandey, The Historical Geography and Topography of Bihar (Motilal Barnarsidass, 1963), p.101

- ^ O.P. Bharadwaj Studies in the Historical Geography of Ancient India (Sundeep Prakashan, 1986), p.210

- ^ R.S. Sharma, Sudras in Ancient India: A Social History of the Lower Order Down to Circa A.D. 600 (Motilal Banarsidass, 1990), p.12

- ^ Tewari, Rakesh (2016). EXCAVATION AT JUAFARDIH, DISTRICT NALANDA. ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA. pp. 6–8.

Layers 13 the uppermost deposit of Period I, has provided a C14 date of 1354 BCE it may thus be seen that the C14 dates of Period I and II are consistent and justifiably indicate that the conventional date bracket for NBPW requires a fresh review at least for the sites in Magadh region.

- ^ Raychaudhuri (1972)

- ^ "बलिराजगढ़- एक प्राचीन मिथिला नगरी".

- ^ "नालंदा ने आनंदित किया लेकिन मिथिला के बलिराजगढ़ की कौन सुध लेगा ? | News of Bihar". Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Krishna Reddy (2003). Indian History. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill. pp. A107. ISBN 0-07-048369-8.

- ^ Mary Pat Fisher (1997) In: Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths I. B. Tauris : London ISBN 1-86064-148-2 - Jainism's major teacher is the Mahavira, a contemporary of the Buddha, and who died approximately 526 BCE. Page 114

- ^ Mary Pat Fisher (1997) In: Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths I. B. Tauris : London ISBN 1-86064-148-2 - "The extreme antiquity of Jainism as a non-vedic, indigenous Indian religion is well documented. Ancient Hindu and Buddhist scriptures refer to Jainism as an existing tradition which began long before Mahavira." Page 115

- ^ Bindloss, Joe; Sarina Singh (2007). India: Lonely planet Guide. Lonely Planet. p. 556. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India, Volumes 1-5. Popular Prakashan. p. 208. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A history of India. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

- ^ Vin.i.268

- ^ Radha Kumud Mookerji, Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, 4th ed. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1988 [1966]), 31, 28–33.

- ^ The Edicts of Ashoka is a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka

- ^ "The First Indian Empire". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Archaeology Gandhara's wonders". Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008. Edicts of Ashoka at Shahbaz Garhi are among the oldest historical "documents" found on the subcontinent.

- ^ "KING ASHOKA: His Edicts and His Times". Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2006. Edicts of Ashoka, which comprise the earliest decipherable corpus of written documents from India, have survived throughout the centuries because they are written on rocks and stone pillars.

- ^ Cooke, Roger (1997). "The Mathematics of the Hindus". The history of mathematics. Wiley. p. 204. ISBN 9780471180821.

Aryabhata himself (one of at least two mathematicians bearing that name) lived in the late 5th and the early 6th centuries at Kusumapura (Pataliutra, a village near the city of Patna) and wrote a book called Aryabhatiya.

- ^ According to the Ashokavadana.

- ^ Sir John Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi", Eastern Book House, 1990, ISBN 81-85204-32-2, pg.38

- ^ E. Lamotte: History of Indian Buddhism, Institut Orientaliste, Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 (1958)

- ^ Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas by Romila Thapar, Oxford University Press, 1960 P200

- ^ "Skanda Gupta (Gupta ruler) - Britannica Online Encyclopaedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ [1] Golden Age of India Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Creative Metal Work, Metal Origins History, Metal Work Techniques". Indiaheritage.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Story of the Delhi Iron Pillar. By R. Balasubramaniam. Published by Foundation Books, 2005. ISBN 9788175962781

- ^ Omalley L S S, History of Magadh, Veena Publication, 2005, ISBN 81-89224-01-8

- ^ Cultural Pasts: Essays in Early Indian History, 2003; Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-566487-6

- ^ Karl J. Schmidt (2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 9781317476818.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age. p. 246. ISBN 9788122411980.

- ^ The Making of India by A. Yusuf Ali p.60

- ^ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.145

- ^ a b c d Prasad Sinha, Bindeshwari (1974). Comprehensive History Of Bihar, Volume 1, Part 2. KP Jayaswal Research Institute. p. 375-403.

- ^ Scott, David (May 1995). "Buddhism and Islam: Past to Present Encounters and Interfaith Lessons". Numen. 42 (2): 141–155. doi:10.1163/1568527952598657. JSTOR 3270172.

- ^ Historia Religionum: Handbook for the History of Religions By C. J. Bleeker, G. Widengren page 381

- ^ Gopal Ram, Rule Hindu Culture During and After Muslim, pp. 20, "Some invaders, like Bakhtiar Khilji, who did not know the value of books and art objects, destroyed them in large numbers and also the famous Nalanda ..."

- ^ The Maha-Bodhi By Maha Bodhi Society, Calcutta (page 8)

- ^ Omalley L.S.S., History of Magadha, Veena Publication, Delhi, 2005, pp. 35.

- ^ Smith V. A., Early history of India

- ^ Islam at War: A History By Mark W. Walton, George F. Nafziger, Laurent W. Mbanda (page 226)

- ^ Sinha, CPN (1969). "Origin of the Karnatas of Mithila - A Fresh Appraisal". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 31: 66–72. JSTOR 44138330.

- ^ Pankaj Jha (20 November 2018). A Political History of Literature: Vidyapati and the Fifteenth Century. OUP India. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-19-909535-3.

- ^ Balogh, Daniel (2021). Pithipati Puzzles: Custodians of the Diamond Throne. British Museum Research Publications. pp. 40–58. ISBN 9780861592289.

- ^ Singh, Pradyuman (19 January 2021). Bihar General Knowledge Digest. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789352667697.

- ^ Niyogi, Rama (1951). "The Khayaravāla Dynasty". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 14: 117–122. JSTOR 44303949.

- ^ Hussain, Ejaz (2017). Shiraz-i Hind: A History of Jaunpur Sultanate. Manohar. pp. 76–78.

- ^ Omalley L.S.S., History of Magadha, Veena Publication, Delhi, 2005, pp. 36, "Sher Shah on his return from Bengal, in 1541, came to Patna, then a small town dependent on Bihar, which was the seat of the local government. He was standing on the ban of the Ganges, when, after much reflection, he said to those who were standing by, "If a fort were to be built in this place, the waters of the Ganges could never flow far from it, and Patna would become one of the great towns of this country." The fort was completed. Bihar for that time was deserted, and fell to ruin; while Patna became one of the largest cities of the province. In 1620 we find Portuguese merchants at Patna; and Tavernier's account shows that a little more than a century after its foundation it was the great entrepot of Northern India "the largest town in Bengal and the most famous for trade..."

- ^ Elliot, History of India, Vol 4

- ^ Tripathi, R. P. "Rise and Fall of Mughal Empire", Allahabad (1960), p,.158

- ^ De Laet, "The Empire of the Great Mogul", pp.140-41

- ^ Ahmed, Nizamuddin. "Tahaqat-i-Akbari", Vol.II, p.114

- ^ Bhardwaj, K. K. "Hemu-Napoleon of Medieval India", Mittal Publications, New Delhi, p.25

- ^ Tahir Hussain Ansari (20 June 2019). Mughal Administration and the Zamindars of Bihar. Taylor & Francis. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-00-065152-2.

- ^ Omalley L.S.S., History of Magadha, Veena Publication, Delhi, 2005, pp. 37

- ^ "Patna at a Glance". Drdapatna.bih.nic.in. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ [2] Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gilani, Najam (7 February 2007). "Thus Spoke Laloo Yadav". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- ^ Anand A. Yang; Professor and Chair and Professor Golub Professor of International Studies Anand A Yang (1 January 1989). The Limited Raj: Agrarian Relations in Colonial India, Saran District, 1793-1920. University of California Press. pp. 63–68. ISBN 978-0-520-05711-1.

- ^ "Veer Kunwar Singh - Hero of 1857 revolts against British imperialists. (By Ankur Bhadauria)". Shvoong.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "History of Bhojpur". Bhojpur.bih.nic.in. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Chandradeo Verma". India Press. Archived from the original on 3 January 2005. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Lok Sabha Members Bioprofile-". Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Kamat. "Great freedom Fighters". Kamat's archive. Archived from the original on 20 February 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ Brown (1972). Gandhi's Rise to Power, Indian Politics 1915-1922: Indian Politics 1915-1922. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-09873-1.

- ^ Indian Post. "First Bihar Deputy CM cum Finance Minister; Dr. A. N. Sinha". official Website. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ SINGH, JAGPAL. “Karpoori Thakur: A Socialist Leader in the Hindi Belt.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 50, no. 3, 2015, pp. 54–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24481124. Accessed 28 July 2023.

- ^ Bandyopādhyāya, Śekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Longman. pp. 523 (at p 406). ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- ^ Bandyopādhyāya, Śekhara (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Longman. pp. 523 (at p 407). ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- ^ WHO'S WHO OF INDIAN MARTYRS VOL. India: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 1969. ISBN 978-81-230-2180-5.

- ^ "Prabhu Narayan gave martyrdom at the age of 21 for country". Hindustan. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Ian Stephens, Pakistan (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1963), p. 111.

- ^ S Shankar. "The Sri Babu-Anugrah babu government". website. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2005.

- ^ Kamat. "Anugrah Narayan Sinha". Kamat's archive. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ Dr. Rajendra Prasad's Letters to Anugrah Narayan Sinha (1995). First Finance cum Labour Minister. Rajendra Prasad's archive. ISBN 978-81-7023-002-1. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- ^ a b Radhakanta Barik (2006). Land and Caste Politics in Bihar. Shipra Publications. p. 85. ISBN 8175413050. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

It is not so as the political party led the national movement and controlled the government for almost 40 years in Bihar after Independence, it would be over-exaggeration to state that the Congress Party is a party of the upper castes.

- ^ a b Shyama Nand Singh (1991). Reservation: Problems and Prospects. Uppal Publishing House. p. 45. ISBN 8185024901. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

The victory of the Congress Party in 1972 arrested this trend. The political domination of the upper castes under the leadership of the Brahmans returned [...] The Coalition Government of five opposition parties in 1967 was led by Mahamaya Prasad Sinha, a Kayastha leader, who had newly formed a political party called the [...] Political power in Bihar was for long the privilege of the upper castes .

- ^ "One-week CM holds real Nayak flag – Ex-chief minister with many firsts recalls wonder days". Nalin Verma. Telegraph India. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. p. 80,81,82. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Caste wars: Bloody pages of Bihar's history". NDTV.com. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "A lasting signature on Bihar's most violent years". Indian Express. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Omvedt, Gail (1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 58–60. ISBN 0765631768. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Ram, Nandu (2009). Beyond Ambedkar: Essays on Dalits in India. Har Anand Publications. ISBN 978-8124114193. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Why The War Never Dies | Outlook India Magazine". outlookindia. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Why the BJP Is Likely to 'Dump' Bihar CM Nitish Kumar in 2020". The Quint. 13 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Ranabir Samaddar (3 March 2016). "Bihar 1990-2011". Government of Peace: Social Governance, Security and the Problematic of Peace. Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1317125372. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Zarhani, Seyed Hossein (2018). "Elite agency and development in Bihar: confrontation and populism in the era of Garibon Ka Masiha". Governance and Development in India: A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after Liberalization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351255189.

- ^ a b Christophe Jaffrelot (2003). India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 379–380. ISBN 8178240807. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Ram Vilas Paswan: The champion of Dalit politics in Bihar". The Economic Times. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Paranjoy Guha Thakurta; Shankar Raghuraman (2007). Divided We Stand: India in a Time of Coalitions. SAGE Publications India. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-8132101642. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ M. Govinda Rao; Arvind Panagariya (2015). The Making of Miracles in Indian States: Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and Gujarat. Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0190236649. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Sanjay Kumar (2018). "Re-emergence of RJD: elections of 2000". Post-Mandal Politics in Bihar: Changing Electoral Patterns. SAGE publishing India. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-9352805860. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Jason A. Kirk (2010). India and the World Bank: The Politics of Aid and Influence. Anthem Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0857289513. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ Kumod Verma (14 February 2008). "Scared Biharis arrive from Mumbai". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Wasbir Hussain. "30 Killed in Northeast Violence in India". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ Patnadaily (6 January 2007). "40 Bihari Workers Killed by ULFA Activists in Assam". Patnadaily.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2006.

- ^ The Hindu (20 March 2012). "Bihar's growth brought down migration of labourers: Nitish". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali (Selected works of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati) in Six volumes published by Prakashan Sansthan, Delhi, 2003.

- Swami Sahajanand and the Peasants of Jharkhand: A View from 1941 translated and edited by Walter Hauser along with the unedited Hindi original (Manohar Publishers, paperback, 2005).