History of East Germany

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 33 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 33 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), German: Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR), often known in English as East Germany, existed from 1949 to 1990.[1] It covered the area of the present-day German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Berlin (excluding West Berlin), Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt, and Thüringen. This area was occupied by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II excluding the former eastern lands annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union, with the remaining German territory to the west occupied by the British, American, and French armies. Following the economic and political unification of the three western occupation zones under a single administration and the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, known colloquially as West Germany) in May 1949, the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany) was formally founded on 7 October 1949 as a sovereign nation.

East Germany's political and economic system reflected its status as a part of the Eastern Bloc of Soviet-allied Communist countries, with the nation ruled by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) and operating with a command economy for 41 years until 3 October 1990 when East and West Germany were unified with the former being absorbed into the latter's existing system of liberal democracy and a market economy.

Creation, 1945–1949

[edit]Division of Germany

[edit]

The Yalta Conference

[edit]At the Yalta Conference, held in February 1945, the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union agreed on the division of Germany into occupation zones. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin favored the maintenance of German unity, but supported its division among the Allies, a view that he reiterated at Potsdam.[2] Estimating the territory that the converging armies of the western Allies and the Soviet Union would overrun, the Yalta Conference determined the demarcation line for the respective areas of occupation. It was also decided that a "Committee on Dismemberment of Germany" was to be set up. The purpose was to decide whether Germany was to be divided into several nations, and if so, what borders and inter-relationships the new German states were to have. Following Germany's surrender, the Allied Control Council, representing the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, assumed governmental authority in postwar Germany. Economic demilitarization however (especially the stripping of industrial equipment) was the responsibility of each zone individually.

The Potsdam Conference

[edit]The Potsdam Conference of July/August 1945 officially recognized the zones and confirmed jurisdiction of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (German: Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland, SMAD) from the Oder and Neisse rivers to the demarcation line. The Soviet occupation zone included the former states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. The city of Berlin was placed under the control of the four powers. The German territory east of the Oder-Neisse line, equal in size to the Soviet occupation zone, was handed over to Poland and the Soviet Union for de facto annexation. This territory transfer was seen as a compensation for Nazi German military occupation of Poland and parts of the Soviet Union. The millions of Germans still remaining in these areas under the Potsdam Agreement were over a period of several years expelled and replaced by Polish settlers (see Expulsion of Germans after World War II), while millions of ethnic Germans from other Eastern European countries poured into Allied-occupied Germany. This migration was to such an extent that by the time the German Democratic Republic was founded, between a third and a quarter of the population of East Germany was Heimatvertriebene, i.e. ethnic German migrants who fled or were expelled as part of a wider trend of population transfer among the countries and regions of Eastern Europe following World War II.[3]

Reparations

[edit]

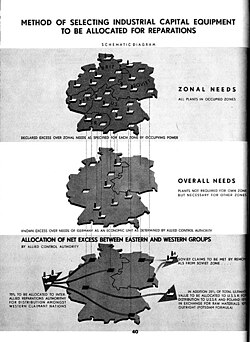

Each occupation power assumed rule in its zone by June 1945. The powers originally pursued a common German policy, focused on denazification and demilitarization in preparation for the restoration of a democratic German nation-state. Over time, however, the western zones and the Soviet zone drifted apart economically, not least because of the Soviets' much greater use of disassembly of German industry under its control as a form of reparations. Reparations were officially agreed among the Allies from 2 August 1945, with 'removals' prior to this date not included. According to Soviet Foreign Ministry data, Soviet troops, organised in specialised "trophy" battalions, removed 1.28m tons of materials[clarification needed] and 3.6m tons of equipment, as well as large quantities of agricultural produce).[4] No agreement on reparations could be reached at the Potsdam Conference, but by December 1947 it was clear that Western governments were unwilling to accede to the Soviet request for $10bn in reparations (which the Soviets placed into perspective by calculating total war damage of $128bn).[5] (In contrast the Germans estimate a total loss of German property, due to the border changes promoted by the USSR and the population expulsions, of 355.3 billion Deutschmarks).[6] As a result, the Soviets sought to extract the $10bn from its occupation zone in eastern Germany, in addition to the trophy removals[clarification needed]; Naimark (1995) estimates that $10bn was transferred in material form by the early 1950s, including in 1945 and 1946 over 17,000 factories, amounting to a third of the productive capital of the eastern occupation zone.[7]

In the western zones, dismantling and/or destruction of German industry continued until 1951 in accordance to the (several times modified) "German level of industry" agreement connected with the Potsdam Conference whereby Germany was to be treated as a single unit and converted into an "agricultural and light industry economy". By the end of 1948 the US had dismantled or destroyed all war-related manufacturing capability in its occupation zone.[8] In accordance with the agreements with the USSR, shipment of dismantled industrial installations from the west began on March 31, 1946. Under the terms of the agreement the Soviet Union would in return ship raw materials such as food and timber to the western zones. When the Soviets did not fulfil their side of the agreement, the US temporarily halted shipments east, and they were never resumed. It was later shown that although these events were subsequently used for cold war propaganda purposes against the Soviet Union, the main reason for halting shipments east was not the behaviour of the USSR but rather the recalcitrance of France.[9] Material received by the USSR included equipment from the Kugel-Fischer ballbearing plant at Schweinfurt, the Daimler-Benz underground aircraft-engine plant at Obrigheim, the Deschimag shipyards at Bremen-Weser, and Gendorf power station.[10][11]

Military industries and those owned by the state, by Nazi activists, and by war criminals were confiscated by the Soviet occupation authority. These industries amounted to about 60% of total industrial production in the Soviet zone. Most heavy industry (constituting 20% of total production) was claimed by the Soviet Union as reparations, and Soviet joint stock companies (German: Sowjetische Aktiengesellschaften—SAG) were formed. The remaining confiscated industrial property was nationalized, leaving 40% of total industrial production to private enterprise.

Agrarian reforms

[edit]The agrarian reform (Bodenreform) expropriated all land belonging to owners of more than 100 hectares of land as well as former Nazis and war criminals and generally limited ownership to 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi). Some 500 Junker estates were converted into collective people's farms (German: Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaft—LPG), and more than 30,000 square kilometres (12,000 sq mi) were distributed among 500,000 peasant farmers, agricultural laborers, and refugees. State farms were also set up, called Volkseigenes Gut (State-owned Property).

Political tensions

[edit]Growing economic differences combined with developing political tensions between the US and the Soviet Union (which would eventually develop into the Cold War) were manifested in the refusal in 1947 of the SMAD to take part in the USA's Marshall Plan. In March 1948, the United States, Britain and France met in London and agreed to unite the Western zones and to establish a West German republic. The Soviet Union responded by leaving the Allied Control Council, and prepared to create an East German state. The division of Germany was made clear with the currency reform of 20 June 1948, which was limited to the western zones. Three days later a separate currency reform was introduced in the Soviet zone. The introduction of the Deutsche Mark to the western sectors of Berlin, against the will of the Soviet supreme commander, led the Soviet Union to introduce the Berlin Blockade to try to gain control of the whole of Berlin. The Western Allies decided to supply Berlin via an airbridge. This lasted 11 months until the Soviet Union lifted the blockade on 12 May 1949.

Political developments

[edit]An SMAD decree of June 10, 1945 allowed the formation of antifascist democratic political parties in the Soviet zone; elections to new state legislatures were scheduled for October 1946. A democratic-antifascist coalition, which included the KPD, the SPD, the new Christian Democratic Union (Christlich-Demokratische Union—CDU), and the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany (Liberal Demokratische Partei Deutschlands—LDPD), was formed in July 1945. The KPD (with 600,000 members, led by Wilhelm Pieck) and the SPD in East Germany (with 680,000 members, led by Otto Grotewohl), which was under strong pressure from the Communists, merged in April 1946 to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands—SED) under pressure from the occupation authorities. In the October 1946 elections, the SED polled approximately 50% of the vote in each state in the Soviet zone. However, a truer picture of the SED's support was revealed in Berlin, which was still undivided. The Berlin SPD managed to preserve its independence and, running on its own, polled 48.7% of the vote while the SED, with 19.8%, was third in the voting behind the SPD and the CDU.

In May 1949, elections were held in the Soviet zone for the German People's Congress to draft a constitution for a separate East German state. Members of the Nazi party were drawn and elections were held from the slate of candidates drawn from different organizations of the anti-fascist coalition. Communists won this election, thereby holding a majority of seats in the People's Congress. According to official results, two-thirds of voters approved the unity lists.

The SED was structured as a Soviet-style "party of the new type". To that end, German communist Walter Ulbricht became first secretary of the SED, and the Politburo, Secretariat, and Central Committee were formed. According to the Leninist principle of democratic centralism, each party body was controlled by its members, meaning that Ulbricht, as party chief, theoretically carried out the will of the members of his party.

Incidentally, the party system was designed to allow re-entry of only those former NSDAP adherents who had earlier decided to join the National Front, which was originally formed by emigrants and prisoners of war in the Soviet Union during World War II. Political denazification in the Soviet zone was thus handled rather more transparently than in the Western zones, where the issue soon came second to considerations of practicality or even just privacy.[citation needed]

In November 1948, the German Economic Commission (Deutsche Wirtschaftskomission—DWK), including antifascist bloc representation, assumed administrative authority. Five months after declaration of the western Federal Republic of Germany (better known as West Germany), on October 7, 1949, the DWK formed a provisional government and proclaimed the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). Wilhelm Pieck, a party leader, was elected first president. On October 9, the Soviet Union withdrew her East Berlin headquarters, and subsequently it outwardly surrendered the functions of the military government to the new German state.

Early years, 1949–1955

[edit]SED as leading party

[edit]

The SED controlled the National Front coalition, a federation of all political parties and mass organizations that preserved political pluralism. The 1949 constitution formally defined East Germany as a quasi-unitary republic with a bicameral parliament comprising an upper house called the Länderkammer (States Chamber) and a lower house called the Volkskammer (People's Chamber). The Volkskammer, defined as the highest state body, was vested with legislative sovereignty. The SED controlled the Council of Ministers and reduced the legislative function of the Volkskammer to that of acclamation. Election to the Volkskammer and the state legislatures (later replaced by district legislatures) was based on a joint ballot prepared by the National Front: voters could register their approval or disapproval.

All members of the SED who were active in state organs carried out party resolutions. The State Security Service (Staatssicherheitsdienst, better known as the Stasi) and the Ministry of State Security had a role similar to Soviet intelligence agencies.

The Third SED Party Congress convened in July 1950 and emphasized industrial progress. The industrial sector, employing 40% of the working population, was subjected to further nationalization, which resulted in the formation of the People's Enterprises (Volkseigener Betrieb—VEB). These enterprises incorporated 75% of the industrial sector. The First Five-Year Plan (1951–55) introduced centralized state planning; it stressed high production quotas for heavy industry and increased labor productivity. The pressures of the plan caused an exodus of East German citizens to West Germany. The second Party Conference (less important than Party Congress) convened on July 9–12, 1952. 1,565 delegates, 494 guest-delegates, and over 2,500 guests from the GDR and from many other countries in the world participated in it. In the conference a new economic policy was adopted, "Planned Construction of Socialism". The plan called to strengthen the state-owned sector of the economy, further to implement the principles of uniform socialist planning, and to use the economic laws of socialism systematically.

Under a law passed by the Volkskammer in 1950, the age at which Germany's youth may reject parental supervision was lowered from 21 to 18. The churches, while nominally assured of religious freedom, were, nevertheless, subjected to considerable pressure. To retaliate, Cardinal von Preysing, Bishop of Berlin, put the SED in East Germany under an Episcopal ban. There were also other indications of opposition, even from within the government itself. In the fall of 1950 several prominent members of the SED were expelled and arrested as "saboteurs" or "for lacking trust in the Soviet Union." Among them were the Deputy Minister of Justice, Helmut Brandt; the Vice-President of the Volkskammer, Joseph Rambo; Bruno Foldhammer, the deputy to Gerhard Eisler; and the editor, Lex Ende. At the end of 1954 the draft of a new family code was published.

In 1951 monthly emigration figures fluctuated between 11,500 and 17,000. By 1953 an average of 37,000 men, women, and children were leaving each month.

The uprising of June 1953

[edit]Stalin died in March 1953. In June the SED, hoping to give workers an improved standard of living, announced the New Course which replaced the Planned Construction of Socialism. The New Course in East Germany was based on the economic policy initiated by Georgy Malenkov in the Soviet Union. Malenkov's policy, which aimed at improvement in the standard of living, stressed a shift in investment toward light industry and trade and a greater availability of consumer goods. The SED, in addition to shifting emphasis from heavy industry to consumer goods, initiated a program for alleviating economic hardships. This led to a reduction of delivery quotas and taxes, the availability of state loans to private business, and an increase in the allocation of production material.

While the New Course increased the consumer goods workers could get, there were still high production quotas. When work quotas were raised in 1953, it led to the 1953 Uprising. Strikes and demonstrations happened in major industrial centers. The workers demanded economic reforms. The Volkspolizei and the Soviet Army suppressed the uprising, in which approximately 100 participants were killed.

Growing Sovereignty

[edit]In 1954 the Soviet Union granted East Germany sovereignty, and the Soviet Control Commission in Berlin was disbanded. By this time, reparations payments had been completed, and the SAGs had been restored to East German ownership. The five states formerly constituting the Soviet occupation zone also had been dissolved and replaced by fifteen districts (Bezirke) in 1952; the United States, Britain, and France did not recognize the fifteenth district, East Berlin. East Germany began active participation in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) in 1950. In 1955 Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl was invited to Moscow and, between September 17 and 20, concluded the Treaty on Relations between the USSR and the GDR with the Soviet Union which entered into force on October 6. According to its terms the German Democratic Republic was henceforth "free to decide questions of its internal and foreign policy, including its relations with the German Federal Republic as well as with other states." Although Soviet forces would temporarily remain in the country on conditions to be agreed upon, they would not interfere in the internal conditions of its social and political life. The two governments would strengthen the economic, scientific-technical, and cultural relations between them and would consult with each other on questions affecting their interests. On 14 May 1955, East Germany became a member of the Warsaw Pact and in 1956 the National People's Army (Nationale Volksarmee—NVA) was created.

Economic policy, 1956–1975

[edit]Collectivization and nationalization of agriculture and industry, 1956–1963

[edit]

In 1956, at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev repudiated Stalinism. Around this time, an academic intelligentsia within the SED leadership demanded reform. To this end, Wolfgang Harich issued a platform advocating radical changes in East Germany. In late 1956, he and his associates were quickly purged from the SED ranks and imprisoned.

An SED party plenum in July 1956 confirmed Ulbricht's leadership and presented the Second Five-Year Plan (1956–1960). The plan employed the slogan "modernization, mechanization, and automation" to emphasize the new focus on technological progress. At the plenum, the regime announced its intention to develop nuclear energy, and the first nuclear reactor in East Germany was activated in 1957. The government increased industrial production quotas by 55% and renewed emphasis on heavy industry.

The Second Five-Year Plan committed East Germany to accelerated efforts toward agricultural collectivization and nationalization and completion of the nationalization of the industrial sector. By 1958 the agricultural sector still consisted primarily of the 750,000 privately owned farms that comprised 70% of all arable land; only 6,000 Agricultural Cooperatives (Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaften—LPGs) had been formed. In 1958–59 the SED placed quotas on private farmers and sent teams to villages in an effort to encourage voluntary collectivization. In November and December 1959 some law-breaking farmers were arrested by the SSD.

By mid-1960 nearly 85% of all arable land was incorporated in more than 19,000 LPGs; state farms comprised another 6%. By 1961 the socialist sector produced 90% of East Germany's agricultural products. An extensive economic management reform by the SED in February 1958 included the transfer of a large number of industrial ministries to the State Planning Commission. In order to accelerate the nationalization of industry, the SED offered entrepreneurs 50-percent partnership incentives for transforming their firms into VEBs. At the close of 1960, private enterprise controlled only 9% of total industrial production. Production Cooperatives (Produktionsgenossenschaften—PGs) incorporated one-third of the artisan sector during 1960–61, a rise from 6% in 1958.

The Second Five-Year Plan encountered difficulties, and the regime replaced it with the Seven-Year Plan (1959–65). The new plan aimed at achieving West Germany's per capita production by the end of 1961, set higher production quotas, and called for an 85% increase in labor productivity. Emigration again increased, totaling 143,000 in 1959 and 199,000 in 1960. The majority of the emigrants were white collar workers, and 50% were under 25 years of age. The labour drain exceeded a total of 2.5 million citizens between 1949 and 1961.

New Economic System, 1963–1970

[edit]The annual industrial growth rate declined steadily after 1959. The Soviet Union therefore recommended that East Germany implement the reforms of Soviet economist Evsei Liberman, an advocate of the principle of profitability and other market principles for communist economies. In 1963 Ulbricht adapted Liberman's theories and introduced the New Economic System (NES), an economic reform program providing for some decentralization in decision-making and the consideration of market and performance criteria. The NES aimed at creating an efficient economic system and transforming East Germany into a leading industrial nation.

Under the NES, the task of establishing future economic development was assigned to central planning. Decentralization involved the partial transfer of decision-making authority from the central State Planning Commission and National Economic Council to the Associations of People's Enterprises (Vereinigungen Volkseigener Betriebe—VVBs), parent organizations intended to promote specialization within the same areas of production. The central planning authorities set overall production goals, but each VVB determined its own internal financing, utilization of technology, and allocation of manpower and resources. As intermediary bodies, the VVBs also functioned to synthesize information and recommendations from the VEBs. The NES stipulated that production decisions be made on the basis of profitability, that salaries reflect performance, and that prices respond to supply and demand.

The NES brought forth a new elite in politics as well as in management of the economy, and in 1963 Ulbricht announced a new policy regarding admission to the leading ranks of the SED. Ulbricht opened the Politburo and the Central Committee to younger members who had more education than their predecessors and who had acquired managerial and technical skills. As a consequence of the new policy, the SED elite became divided into political and economic factions, the latter composed of members of the new technocratic elite. Because of the emphasis on professionalization in the SED cadre policy after 1963, the composition of the mass membership changed: in 1967 about 250,000 members (14%) of the total 1.8 million SED membership had completed a course of study at a university, technical college, or trade school.

The SED emphasis on managerial and technical competence also enabled members of the technocratic elite to enter the top echelons of the state bureaucracy, formerly reserved for political dogmatists. Managers of the VVBs were chosen on the basis of professional training rather than ideological conformity. Within the individual enterprises, the number of professional positions and jobs for the technically skilled increased. The SED stressed education in managerial and technical sciences as the route to social advancement and material rewards. In addition, it promised to raise the standard of living for all citizens. From 1964 until 1967, real wages increased, and the supply of consumer goods, including luxury items, improved much.

Ulbricht in 1968 launched a spirited campaign to convince the Comecon states to intensify their economic development "by their own means." Domestically the East German regime replaced the NES with the Economic System of Socialism (ESS), which focused on high technology sectors in order to make self-sufficient growth possible. Overall, centralized planning was reintroduced in the so-called structure-determining areas, which included electronics, chemicals, and plastics. Industrial combines were formed to integrate vertically industries involved in the manufacture of vital final products. Price subsidies were restored to accelerate growth in favored sectors. The annual plan for 1968 set production quotas in the structure-determining areas 2.6% higher than in the remaining sectors in order to achieve industrial growth in these areas. The state set the 1969–70 goals for high-technology sectors even higher. Failure to meet ESS goals resulted in the conclusive termination of the reform effort in 1970.

The Main Task

[edit]The Main Task, introduced by Honecker in 1971, formulated domestic policy for the 1970s. The program re-emphasized Marxism–Leninism and the international class struggle. During this period, the SED launched a massive propaganda campaign to win citizens to its Soviet-style socialism and to restore the "worker" to prominence. The Main Task restated the economic goal of industrial progress, but this goal was to be achieved within the context of centralized state planning. Consumer socialism—the new program featured in the Main Task—was an effort to magnify the appeal of socialism by offering special consideration for the material needs of the working class. The state extensively revamped wage policy and gave more attention to increasing the availability of consumer goods.

The regime also accelerated the construction of new housing and the renovation of existing apartments; 60% of new and renovated housing was allotted to working-class families. Rents, which were subsidized, remained extremely low. Because women constituted nearly 50% of the labor force, child-care facilities, including nurseries and kindergartens, were provided for the children of working mothers. Women in the labor force received salaried maternity leave which ranged from six months to one year. The state also increased retirement annuities.

Foreign policy, 1967–1975

[edit]Ulbricht versus détente

[edit]Ulbricht's foreign policy from 1967 to 1971 responded to the beginning of the era of détente with the West. Although détente offered East Germany the opportunity to overcome its isolation in foreign policy and to gain Western recognition as a sovereign state, the SED leader was reluctant to pursue a policy of rapprochement with West Germany. Both German states had retained the goal of future unification; however, both remained committed to their own irreconcilable political systems. In 1968, the SED recast the constitution into a fully Communist document. It declared East Germany to be a socialist state whose power derived from the working class under the leadership of "its Marxist-Leninist party"—thus codifying the actual state of affairs that had existed since 1949. The new constitution proclaimed the victory of socialism and restated the country's commitment to unification under Communist leadership.

However, the SED leadership, although successful in establishing socialism in East Germany, had limited success in winning popular support for the repressive social system. In spite of the epithet "the other German miracle", the democratic politics and higher material progress of West Germany continued to attract East German citizens. Ulbricht feared that hopes for a democratic government or a reunification with West Germany would cause unrest among East German citizens, who since 1961 appeared to have come to terms with social and living conditions.

In the late 1960s, Ulbricht made the Council of State as main governmental organ. The 24-member, multiparty council, headed by Ulbricht and dominated by its fifteen SED representatives, generated a new era of political conservatism. Foreign and domestic policies in the final years of the Ulbricht era reflected strong commitment to an aggressive strategy toward the West and toward Western ideology. Ulbricht's foreign policy focused on strengthening ties with Warsaw Pact countries and on organizing opposition to détente. In 1967 he persuaded Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria to conclude bilateral mutual assistance treaties with East Germany. The Ulbricht Doctrine, subsequently signed by these states, committed them to reject the normalization of relations with West Germany unless Bonn formally recognized East German sovereignty.

Ulbricht also encouraged the abrogation of Soviet bloc relations with the industrialized West, and in 1968 he launched a spirited campaign to convince the Comecon states to intensify their economic development "by their own means." Considering claims for freedom and democracy within the Soviet bloc a danger to its domestic policies, the SED, from the beginning, attacked Prague's new political course, which resulted in intervention by the Soviet military and other Warsaw Pact contingents in 1968.

In August 1970, the Soviet Union and West Germany signed the Moscow Treaty, in which the two countries pledged nonaggression in their relations and in matters concerning European and international security and confirmed the Oder-Neisse line. Moscow subsequently pressured East Germany to begin bilateral talks with West Germany. Ulbricht resisted, further weakening his leadership, which had been damaged by the failure of the ESS. In May 1971, the SED Central Committee chose Erich Honecker to succeed Ulbricht as the party's first secretary. Although Ulbricht was allowed to retain the chairmanship of the Council of State until his death in 1973, the office had been reduced in importance.

Honecker and East-West Rapprochement

[edit]Honecker combined loyalty to the Soviet Union with flexibility toward détente. At the Eighth Party Congress in June 1971, he presented the political program of the new regime. In his reformulation of East German foreign policy, Honecker renounced the objective of a unified Germany and adopted the "defensive" position of ideological Abgrenzung (demarcation or separation). Under this program, the country defined itself as a distinct "socialist state" and emphasized its allegiance to the Soviet Union. Abgrenzung, by defending East German sovereignty, in turn contributed to the success of détente negotiations that led to the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (Berlin Agreement) in 1971 and the Basic Treaty with West Germany in December 1972.

The Berlin Agreement and the Basic Treaty normalized relations between East Germany and West Germany. The Berlin Agreement (effective June 1972), signed by the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, protected trade and travel relations between West Berlin and West Germany and aimed at improving communications between East Berlin and West Berlin. The Soviet Union stipulated, however, that West Berlin would not be incorporated into West Germany. The Basic Treaty (effective June 1973) politically recognized two German states, and the two countries pledged to respect one another's sovereignty. Under the terms of the treaty, diplomatic missions were to be exchanged and commercial, tourist, cultural, and communications relations established. In September 1973, both countries joined the United Nations, and thus East Germany received its long-sought international recognition.

Two German states

[edit]

From the mid-1970s, East Germany remained poised between East and West. The 1974 amendment to the Constitution deleted all references to the "German nation" and "German unity" and designated East Germany "a socialist nation-state of workers and peasants" and "an inseparable constituent part of the socialist community of states." However, the SED leadership had little success in inculcating East Germans with a sense of ideological identification with the Soviet Union. Honecker, conceding to public opinion, devised the formula "citizenship, GDR; nationality, German." In so doing, the SED first secretary acknowledged the persisting psychological and emotional attachment of East German citizens to German traditions and culture and, by implication, to their German neighbors in West Germany.

Although Abgrenzung constituted the foundation of Honecker's policy, détente strengthened ties between the two German states. Between 5 and 7 million West Germans and West Berliners visited East Germany each year. Telephone and postal communications between the two countries were significantly improved. Personal ties between East German and West German families and friends were being restored, and East German citizens had more direct contact with West German politics and material affluence, particularly through radio and television. West Germany was East Germany's supplier of high-quality consumer goods, including luxury items, and the latter's citizens frequented both the Intershops, which sold goods for Western currency, and the Exquisit and Delikat shops, which sold imported goods for East German currency.

As part of the general détente between East and West, East Germany participated in the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe in Europe and in July 1975 signed the Helsinki Final Act, which was to guarantee the regime's recognition of human rights. The Final Act's provision for freedom of movement elicited approximately 120,000 East German applications for permission to emigrate, but the applications were rejected.

Domestic policy, 1970s

[edit]GDR identity

[edit]

From the beginning, the newly formed GDR tried to establish its own separate identity. Because of Marx's abhorrence of Prussia, the SED repudiated continuity between Prussia and the GDR. The SED destroyed the Junker manor houses, wrecked the Berlin city palace, and removed the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great from East Berlin. Instead the SED focused on the progressive heritage of German history, including Thomas Müntzer's role in the German Peasants' War and the role played by the heroes of the class struggle during Prussia's industrialization. Nevertheless, as early as 1956 East Germany's Prussian heritage asserted itself in the NVA.

As a result of the Ninth Party Congress in May 1976, East Germany after 1976–77 considered its own history as the essence of German history, in which West Germany was only an episode. It laid claim to reformers such as Karl Freiherr vom Stein, Karl August von Hardenberg, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and Gerhard von Scharnhorst. The statue of Frederick the Great was meanwhile restored to prominence in East Berlin. Honecker's references to the former Prussian king in his speeches reflected East Germany's official policy of revisionism toward Prussia, which also included Bismarck and the resistance group Red Band. East Germany also laid claim to the formerly maligned Martin Luther and to the organizers of the Spartacus League, Karl Liebknecht, and Rosa Luxemburg.

Dissidents

[edit]In spite of détente, the Honecker regime remained committed to Soviet-style socialism and continued a strict policy toward dissidents. Nevertheless, a critical Marxist intelligentsia within the SED renewed the plea for democratic reform. Among them was the poet-singer Wolf Biermann, who with Robert Havemann had led a circle of artists and writers advocating democratization; he was expelled from East Germany in November 1976 for dissident activities. Following Biermann's expulsion, the SED leadership disciplined more than 100 dissident intellectuals.

Despite the government's actions, East German writers began to publish political statements in the West German press and periodical literature. The most prominent example was Rudolf Bahro's Die Alternative, which was published in West Germany in August 1977. The publication led to the author's arrest, imprisonment, and deportation to West Germany. In late 1977, a manifesto of the "League of Democratic Communists of Germany" appeared in the West German magazine Der Spiegel. The league, consisting ostensibly of anonymous middle- to high-ranking SED functionaries, demanded democratic reform in preparation for reunification.

Even after an exodus of artists in protest against Biermann's expulsion, the SED continued its repressive policy against dissidents. The state subjected literature, one of the few vehicles of opposition and nonconformism in East Germany, to ideological attacks and censorship. This policy led to an exodus of prominent writers, which lasted until 1981. The Lutheran Church also became openly critical of SED policies. Although in 1980-81 the SED intensified its censorship of church publications in response to the Polish Solidarity movement, it maintained, for the most part, a flexible attitude toward the church. The consecration of a church building in May 1981 in Eisenhüttenstadt, which according to the SED leadership was not permitted to build a church owing to its status as a "socialist city", demonstrated this flexibility.

10th Party Congress, 1981

[edit]The 10th Party Congress, which took place in April 1981, focused on improving the economy, stabilizing the socialist system, achieving success in foreign policy, and strengthening relations with West Germany. Presenting the SED as the leading power in all areas of East German society, General Secretary (the title changed from First Secretary in 1976) Honecker emphasized the importance of educating loyal cadres in order to secure the party's position. He announced that more than one-third of all party members and candidates, nearly two-thirds of the party secretaries had completed a course of study at a university, technical college, or trade school, and that four-fifths of the party secretaries had received training in a party school for more than a year.

Stating that a relaxation of "democratic centralism" was unacceptable, Honecker emphasized rigid centralism within the party. Outlining the SED's general course, the congress confirmed the unity of East Germany's economic and social policy on the domestic front and its absolute commitment to the Soviet Union in foreign policy. In keeping with the latter pronouncement, the SED approved the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. The East German stance differed from that taken by the Yugoslav, Romanian, and Italian communists, who criticized the Soviet action.

The SED's Central Committee, which during the 1960s had been an advisory body, was reduced to the function of an acclamation body during the Tenth Party Congress. The Politburo and the Secretariat remained for the most part unchanged. In addition to policy issues, the congress focused on the new Five-Year Plan (1981–85), calling for higher productivity, more efficient use of material resources, and better quality products. Although the previous five-year plan had not been fulfilled, the congress once again set very high goals.

Decline and fall of the GDR, 1975–1989

[edit]Coffee crisis, 1976–1979

[edit]Due to the strong German tradition of drinking coffee, coffee imports were one of the most important for consumers. A massive rise in coffee prices in 1976–77 led to a quadrupling of the annual costs of importing coffee compared to 1972–75. This caused severe financial problems for the GDR, which perennially lacked hard currency.

As a result, in mid-1977 the Politburo withdrew most cheaper brands of coffee from sale, limited use in restaurants, and effectively withdrew its provision in public offices and state enterprises. In addition, an infamous new type of coffee was introduced, Mischkaffee (mixed coffee), which was 51% coffee and 49% a range of fillers, including chicory, rye, and sugar beet.[citation needed]

Unsurprisingly, the new coffee was generally detested for its awful taste, and the whole episode is informally known as the "coffee crisis". The crisis passed after 1978 as world coffee prices began to fall again, as well as increased supply through an agreement between the GDR and Vietnam—the latter becoming one of the world's largest coffee producers in the 1990s. However, the episode vividly illustrated the structural economic and financial problems of the GDR.[citation needed]

Developing international debt crisis

[edit]Although in the end political circumstances led to the collapse of the SED regime, the GDR's growing international (hard currency) debts were leading towards an international debt crisis within a year or two. Debts continued to grow in the course of the 1980s to over DM40 bn owed to western institutions, a sum not astronomical in absolute terms (the GDR's GDP was perhaps DM250bn) but much larger in relation to the GDR's capacity to export sufficient goods to the west to provide the hard currency to service these debts. An October 1989 paper prepared for the Politburo (Schürer-Papier, after its principal author Gerhard Schürer) projected a need to increase export surplus from around DM2bn in 1990 to over DM11bn by 1995 in order to stabilise debt levels.

Much of the debt originated from attempts by the GDR to export its way out of its international debt problems, which required imports of components, technologies, and raw materials; as well as attempts to maintain living standards through imports of consumer goods. The GDR was internationally competitive in some sectors such as mechanical engineering and printing technology. However the attempt to achieve a competitive edge in microchips not only failed, but swallowed increasing amounts of internal resources and hard currency. Another significant factor was the elimination of a ready source of hard currency through re-export of Soviet oil, which until 1981 was provided below world market prices. The resulting loss of hard currency income produced a noticeable dip in the otherwise steady improvement of living standards. (It was precisely this continuous improvement which was at risk due to the impending debt crisis; the Schürer-Papier's remedial plans spoke of a 25–30% reduction.)

Regime collapse, 1989

[edit]In May 1989, local government elections were held. The public reaction was one of anger, when it was revealed that National Front candidates had won the majority of seats, with 'only' 98.5% of the vote. In other words, despite larger-than-ever numbers of voters rejecting the single candidate put forward by the Front (an exercise of defiance that carried great risk—including being sacked from a job or expelled from university), the vote had been flagrantly rigged.[12] Increasing numbers of citizens applied for exit visas or left the country illegally. In August 1989, Hungary's reformist government removed its border restrictions with Austria—the first breach in the so-called "Iron Curtain". In September 1989, more than 13,000 East Germans managed to escape to the West through Hungary. The Hungarian government told their furious East German counterparts that international treaties on refugees took precedence over a 1969 agreement between the two countries restricting freedom of movement. Thousands of East Germans also tried to reach the West by staging sit-ins at West German diplomatic facilities in other East European capitals, especially in Prague, Czechoslovakia. The GDR subsequently announced that it would provide special trains to carry these refugees to West Germany, claiming it was expelling "irresponsible antisocial traitors and criminals."[13] Meanwhile, mass demonstrations in Dresden and Leipzig demanded the legalization of opposition groups and democratic reforms.

Virtually ignoring the problems facing the country, Honecker and the rest of the Politburo celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Republic in East Berlin on October 7. As in past celebrations, soldiers marched on parade and missiles were displayed on large trucks to showcase the Republic's weaponry. However, the parade proved to be a harbinger. With Mikhail Gorbachev and most of the Warsaw Pact leaders in attendance, members of the FDJ were heard chanting, "Gorby, help us! Gorby, save us!" That same night, the first of many large demonstrations occurred in East Berlin, the first mass demonstration in the capital itself. Similar demonstrations for freedom of speech and of the press erupted across the country and increased pressure on the regime to reform. One of the largest occurred in Leipzig. Troops had been sent there—almost certainly on Honecker's orders—only to be pulled back by local party officials. In an attempt to ward off the threat of popular uprising, the Politburo ousted Honecker on October 18.[12]

Honecker's replacement was Egon Krenz, the regime's number-two man for most of the second half of the 1980s. Although he was almost as detested as Honecker himself, he made promises to open up the regime from above. Few East Germans were convinced, however; the demonstrations continued unabated. Additionally, people continued to flee to West Germany in increasing numbers, first through Hungary and later through Czechoslovakia. At one point, several schools had to close because there were not enough students or teachers to have classes.[12]

On November 9, in an effort to stave off the protests and the mass exodus, the government crafted new travel regulations that allowed East Germans who wanted to go to West Germany (either permanently or for a visit) to do so directly through East Germany. However, no one on the Politburo told the government's de facto spokesman, East Berlin party chief Günter Schabowski, that the new regulations were due to take effect the next day. When a reporter asked when the regulations were to take effect, Schabowski assumed they were already in force and replied, "As far as I know ... immediately, without delay." When excerpts from the press conference were broadcast on West German television, it prompted large crowds to gather at the checkpoints near the Berlin Wall. Unprepared, outnumbered, and unwilling to use force to keep them back, the guards finally let them through. In the following days increasing numbers of East Germans took advantage of this to visit West Germany or West Berlin (where they were met by West German government gifts of DM100 each, called "greeting money").

The fall of the Berlin Wall was, for all intents and purposes, the death certificate for the SED. Communist rule formally ended on December 1, when the Volkskammer deleted the provisions of the Constitution that declared East Germany to be a socialist state under the leadership of the SED. Krenz, the Politburo, and the Central Committee resigned two days later. Hans Modrow, who had been appointed prime minister only two weeks earlier, now became the de facto leader of a country in a state of utter collapse.

Financial situation in 1990

[edit]Little of the structural economic and financial problems identified by the Schürer-Papier were widely known until late 1989 (although in 1988–89 the GDR's creditworthiness was declining slightly). At this time, the government, aware of the impending problems from the October 1989 Schürer-Papier, asked the West German government for new billion-Deutschmark loans. Although the financial problems probably played no role in the opening of the borders on November 9, opening the borders eliminated any West German interest in further supporting the East German state, as West Germany immediately began to work towards a reunification. As a result, the new East German transitional government faced massive medium-term financial problems, which might—as the Schürer-Papier had even suggested—lead to the International Monetary Fund being called in, although in the short-term gold and other reserves ensured that bills continued to be paid. In the event, massive West German financial support (around half East Germany's budget in 1990) following the March 1990 elections prevented a financial collapse in the months leading up to reunification.

Reunification

[edit]Although there were some small attempts to create a non-socialist East Germany, these were soon overwhelmed by calls for reunification with West Germany. There were two main legal routes for this. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic explicitly stated that it was only intended for temporary use until a permanent constitution could be adopted by the German people. This was largely out of necessity, because at the time it was written (1949) it could not extend its authority to the East. The Basic Law therefore provided a means (Article 146) for a new constitution to be written for a united and democratic Germany. The other route was Article 23, under which prospective states could accede to the Federal Republic by simple majority vote, in the process accepting its existing laws and institutions. This had been used in 1957 for the accession of the state of Saarland. Whilst Article 146 had been expressly designed for the purpose of German reunification, it was apparent in 1990 that employing it would require a vastly longer and more complex process of negotiation—and one which would open up many political issues in West Germany, where constitutional reform (particularly to respond to changing economic circumstances) was a longstanding concern. Even without this to consider, East Germany was virtually prostrate economically and politically.

With these factors in mind, it was decided to use the quicker process in Article 23. Under this route, reunification could be implemented in just six months, and completely sidestep the West German political conflicts involved in writing a new constitution. Under the pressure of an increasing financial crisis (driven partly by mass emigration to West Germany in early 1990 and partly by the Federal Republic's refusal to grant the loans that would have been needed to underpin a longer transition period), the Article 23 route rapidly became the frontrunner. The cost of this, however, was that East Germany's nascent democracy died less than a year after it was born, with a set of laws and institutions imposed from outside replacing a set of laws and institutions imposed from above. Any debate, for example, about the value of the various social institutions (such as the childcare, education, and healthcare systems, which had implemented policy ideas discussed in West Germany for decades, and still today) was simply ruled out by this legal route.[citation needed]

East Germany held its first free elections in March 1990. The SED had reorganized as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and pushed out most of its hardline Communist members in hopes of rehabilitating its image. It was to no avail; as expected, the PDS was heavily defeated by the Alliance for Germany, a centre-right coalition dominated by the East German branch of the CDU and running on a platform of speedy reunification with West Germany. A "grand coalition" of the Alliance and the revived Social Democrats elected the CDU's Lothar de Maizière as Prime Minister on April 12. Following negotiations between the two German states, a Treaty on Monetary, Economic, and Social Union was signed on May 18 and came into effect on July 1, among things replacing the East German mark with the Deutsche Mark (DM). The treaty also declared the intention for East Germany to join the Federal Republic by way of the Basic Law's Article 23 and indeed laid much of the ground for this by providing for the swift and wholesale implementation of West German laws and institutions in East Germany.[14]

In mid-July most state property—covering a large majority of the East German economy—was transferred to the Treuhand, which was given the responsibility of overseeing the transformation of East German state-owned business into market-oriented privatised companies. On July 22 a law was passed recreating the five original federal states of East Germany, to take effect on October 14; and on August 31 the Unification Treaty set an accession date of October 3 (modifying the State Creation Law to come into effect on that date). The Unification Treaty declared that (with few exceptions) at accession the laws of East Germany would be replaced overnight by those of West Germany. The Volkskammer approved the treaty on September 20 by a margin of 299-80—in effect, voting East Germany out of existence.

In September, after some negotiations which involved the United States, the Soviet Union, France, and the United Kingdom, conditions for German reunification were agreed on, with the Allies of World War II renouncing their former rights in Germany and agreeing to remove all occupying troops by 1994. In separate negotiations between Gorbachev and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, it was agreed that a reunified Germany would be free to choose whatever alliance it wanted, though Kohl made no secret that a reunified Germany would inherit the West German seats at NATO and the European Community. With the 12 September signing of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, Germany became fully sovereign once more from March 15, 1991. On October 3, 1990, East Germany formally ceased to exist. The five recreated states in its former territory acceded to the Federal Republic, while East and West Berlin reunited to form the third city-state of the Federal Republic. Thus the East German population was the first from the Eastern Bloc to join the EC as a part of the reunified Federal Republic of Germany (see German reunification).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Birth of the German Democratic Republic". German Culture. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (1995). The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation, 1945-1949. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Kopstein, Jeffrey (1997). The Politics of Economic Decline in East Germany, 1945-1989. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 281. ISBN 0-8078-5707-6.

- ^ Naimark (1995), The Russians in Germany, p167

- ^ Naimark (1995), The Russians in Germany, p168

- ^ Manfred Görtemaker, Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Von der Gründung bis zur Gegenwart, C. H. Beck, 1999, p.171, ISBN 3-406-44554-3 [1]

- ^ Naimark (1995), The Russians in Germany, p169

- ^ "GHDI - Document - Page".

- ^ John Gimbel, "The American Reparations Stop in Germany: An Essay on the Political Uses of History"

- ^ "GHDI - Document - Page".

- ^ "Potsdam Reparations Begin" (PDF). wisc.edu. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- ^ [2] Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Treaty on Monetary, Economic and Social Union

External links

[edit]- End of East Germany and Following Problems from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- LOC Country studies (public domain text)

- RFE/RL East German Subject Files, Blinken Open Society Archives, Budapest

- Der Demokrat (German)

- DDR Wissen (German)

- Tillis Story

- Memories of the former FRG Ambassador in Prague of the exodus of GDR citizens through the West German Prague embassyin 1989 (German)

- Time line of East German history

KSF

KSF