History of Pomerania

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 37 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 37 min

| History of Pomerania |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Pomerania starts shortly before 1000 AD, with ongoing conquests by newly arrived Polan rulers. Before that, the area was recorded nearly 2000 years ago as Germania, and in modern times Pomerania has been split between Germany and Poland. Its name comes from the Old Polish po more, which means "(land) at the sea".[1]

Settlement in the area started by the end of the Vistula Glacial Stage, about 13,000 years ago.[2] Archeological traces have been found of various cultures during the Stone and Bronze Age, of Veneti and Germanic peoples during the Iron Age and, in the Middle Ages, Slavic tribes and Vikings.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] Starting in the 10th century, Piast Poland on several occasions acquired parts of the region from the south-east, while the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark reached the region in augmenting their territory to the west and north.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

In the High Middle Ages, the area became Christian and was ruled by local dukes of the House of Pomerania and the Samborides, at various times vassals of Denmark, the Holy Roman Empire and Poland.[16][17][18] From the late 12th century, the Griffin Duchy of Pomerania stayed with the Holy Roman Empire and the Principality of Rügen with Denmark, while Denmark, Brandenburg, Poland and the Teutonic Knights struggled for control in Samboride Pomerelia.[18][19][20] The Teutonic Knights succeeded in annexing Pomerelia to their monastic state in the early 14th century. Meanwhile, the Ostsiedlung started to turn Pomerania into a German-settled area; the remaining Wends, who became known as Slovincians and Kashubians, continued to settle within the rural East.[21][22] In 1325, the line of the princes of Rügen died out, and the principality was inherited by the House of Pomerania,[23] themselves involved in the Brandenburg-Pomeranian conflict about superiority in their often internally divided duchy. In 1466, with the Teutonic Order's defeat, Pomerelia became subject to the Polish Crown as a part of Royal Prussia.[24] While the Duchy of Pomerania adopted the Protestant Reformation in 1534,[25][26][27] as part of the Empire by then termed the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation,[28] Kashubia remained with the Roman Catholic Church. The Thirty Years' and subsequent wars severely ravaged and depopulated most of Pomerania.[29] With the extinction of the Griffin house during the same period, the Duchy of Pomerania was divided between the Swedish Empire and Brandenburg-Prussia in 1648.

Prussia gained the southern parts of Swedish Pomerania in 1720.[30] It gained the remainder of Swedish Pomerania in 1815, when French occupation during the Napoleonic Wars was lifted.[31] The former Brandenburg-Prussian Pomerania and the former Swedish parts were reorganized into the Prussian Province of Pomerania,[32] while Pomerelia in the partitions of Poland was made part of the Province of West Prussia. With Prussia, both provinces joined the newly constituted German Empire in 1871. Following the empire's defeat in World War I, Pomerelia became part of the Second Polish Republic (Polish Corridor) and the Free City of Danzig was created. Germany's Province of Pomerania was expanded in 1938 to include northern parts of the former Province of Posen–West Prussia, and in 1939 the annexed Polish territories became the part of Nazi Germany known as Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia. The Nazis deported the Pomeranian Jews to a reservation near Lublin[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42] and mass-murdered Jews, Poles and Kashubians in Pomerania, planning to eventually exterminate Jews and Poles and Germanise the Kashubians.

After Nazi Germany's defeat in World War II, the German–Polish border was shifted west to the Oder–Neisse line and all of Pomerania was placed under Soviet military control.[43][44] The area west of the line became part of East Germany, the other areas part of the People's Republic of Poland even though it did not have a sizeable Polish population. The German population of the areas east of the line was expelled, and the area was resettled primarily with Poles (some of whom were themselves expellees from former eastern Poland), and some Ukrainians (who were resettled under Operation Vistula) and Jews.[45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53] Most of Western Pomerania (Vorpommern) today forms the eastern part of the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in Federal Republic of Germany, while the Polish part of the region is divided between West Pomeranian Voivodeship and Pomeranian Voivodeship, with their capitals in Szczecin and Gdańsk, respectively. During the late 1980s, the Solidarność and Die Wende movements overthrew the Communist regimes implemented during the post-war era.[citation needed] Since then, Pomerania has been democratically governed.

Prehistory and antiquity

[edit]

After the glaciers of the Vistula Glacial Stage retreated from Pomerania during the Allerød oscillation,[2] a warming period that falls within the Early Stone Age, they left a tundra. First humans appeared hunting reindeer in the summer.[54] A climate change in 8000 BC[55] allowed hunters and foragers of the Maglemosian culture,[2] and from 6000 BC of the Ertebølle-Ellerbek culture, to continuously inhabit the area.[56] These people became influenced by farmers of the Linear Pottery culture who settled in southern Pomerania.[56][57] The hunters of the Ertebølle-Ellerbek culture became farmers of the Funnelbeaker culture in 3000 BC.[56][58] The Havelland culture dominated in the Uckermark from 2500 to 2000 BC.[59] In 2400 BC, the Corded Ware culture reached Pomerania[59][60] and introduced the domestic horse.[60] Both Linear Pottery and Corded Ware culture have been associated with Indo-Europeans.[60] Except for Western Pomerania,[59] the Funnelbeaker culture was replaced by the Globular Amphora culture a thousand years later.[61]

During the Bronze Age, Western Pomerania was part of the Nordic Bronze Age cultures, while east of the Oder the Lusatian culture dominated.[62] Throughout the Iron Age, the people of the western Pomeranian areas belonged to the Jastorf culture,[63][64] while the Lusatian culture of the East was succeeded by the Pomeranian culture,[63] then in 150 BC by the Oxhöft (Oksywie) culture, and at the beginning of the first millennium by the Willenberg (Wielbark) Culture.[63]

While the Jastorf culture is usually associated with Germanic peoples,[65] the ethnic category of the Lusatian culture and its successors is debated.[66] Veneti, Germanic peoples (Goths, Rugians, and Gepids) and possibly Slavs are assumed to have been the bearers of these cultures or parts thereof.[66]

Beginning in the 3rd century, many settlements were abandoned,[67] marking the beginning of the Migration Period in Pomerania. It is assumed that Burgundians, Goths and Gepids with parts of the Rugians left Pomerania during that stage, while some Veneti, Vidivarii and other, Germanic groups remained,[68] and formed the Gustow, Debczyn and late Willenberg cultures, which existed in Pomerania until the 6th century.[67]

Timeline 10,000 BC–600 AD

[edit]

- ~10,000 BC (Early Stone Age): first humans hunt in Pomerania after the Ice Age glaciers left (Hamburg culture,[3] a subgroup of the Ahrensburg culture)[2]

- 8000–3000 BC (Middle Stone Age): Maglemosian culture,[2] Ertebølle-Ellerbek culture (Lietzow subgroup)[2][6][56]

- 3000–1900 BC (Late Stone Age): Linear Pottery culture,[56][57] Funnelbeaker culture,[56][58] Havelland culture,[59] Corded Ware culture,[59][60] Globular Amphora culture[59]

- 1900–~550 BC (Bronze Age): Nordic Bronze Age (Western Pomerania),[69] Lusatian Culture (Eastern Pomerania)[62]

- ~550 BC–~250 AD (Iron Age): Jastorf culture (Western Pomerania, 550–50 BC),[63][64] Pomeranian culture (Pomerelia, 650–150 BC),[63] Oxhöft (Oksywie) culture (Pomerelia, 150 BC–1 AD), Willenberg (Wielbark) culture (Pomerelia, 1–250 AD).[63] In part associated with Veneti and Germanic peoples[65] like Suebi, Goths, and Rugians.

- since 200: Migration Period: great parts of the population move south, associated with Burgundians, Goths, Gepids, and parts of the Rugians[68]

- 3rd–6th centuries: Gustow group in Western Pomerania, Dębczyn (Denzin) culture in most of Farther Pomerania, late stage of the Willenberg (Wielbark) culture in Pomerelia and some areas west of it. Associated with Rugian remains and other Germanic tribes, Vistula Veneti, and Vidivarii.[68]

Early Middle Ages

[edit]

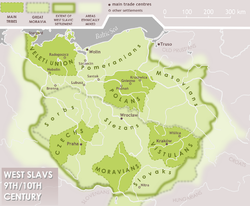

The southward movement of Germanic tribes and Veneti during the Migration Period had left Pomerania largely depopulated by the 7th century.[70] Between 650 and 850 AD, West Slavic tribes settled in Pomerania.[71][72] These tribes were collectively known as "Pomeranians" between the Oder and Vistula rivers, or as "Veleti" (later "Liuticians") west of the Oder. A distinct tribe, the Rani, was based on the island of Rügen and the adjacent mainland.[7][73] In the 8th and 9th centuries, Slavic-Scandinavian emporia were set up along the coastline as powerful centres of craft and trade.[74]

In 936, the Holy Roman Empire set up the Billung and Northern marches in Western Pomerania, divided by the Peene. The Liutician federation, in an uprising of 983, managed to regain independence, but broke apart in the course of the 11th century because of internal conflicts.[9][75] Meanwhile, Polish Piasts managed to acquire parts of eastern Pomerania during the late 960s, where the Diocese of Kołobrzeg was installed in 1000 AD. The Pomeranians regained independence during the Pomeranian uprising of 1005.[10][12][13][failed verification][14][15][76][77][78][79][80]

During the first half of the 11th century, the Liuticians participated in the Holy Roman Empire's wars against Piast Poland.[81] The alliance broke off when Poland was defeated,[82] and the Liutician federation broke apart in 1057 during a civil war.[83] The Liutician capital was destroyed by the Germans in 1068/69,[84] making way for the subsequent eastward expansion of their western neighbour, the Obodrite state. In 1093, the Luticians,[85] Pomeranians[85] and Rani[85] had to pay tribute to Obodrite prince Henry.[86]

Timeline 600–1100

[edit]

- ~650–~850: Slavic peoples appear and differentiate into several tribes grouped as Polabian Veleti (later Liuticians, Lutizians) in the West and Pomeranians in the East,[7][71][87] resettling the regions left by the Germanic tribes

- since 800: various Scandinavian settlements and tradeposts, including Ralswiek, Altes Lager Menzlin, and Wollin (then "Vineta" or "Jomsborg" of the Jomsvikings).[8]

- 918: western parts incorporated into Northern March and March of the Billungs (Duchy of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire)[9]

- 955: Battle of Recknitz ("Raxa"): Germans and Rani suppress an Obodrite revolt in the Billung march[88]

- In the 980s, a stronghold in Gdańsk was built, probably by the Polish ruler Mieszko I, who thereby connected the future Polish state ruled by the Piast dynasty with the trade routes of the Baltic Sea.

- 983: uprising in the marches, Lutici regain independence after forming the Lutici federation[9]

- Mieszko I of Poland launches several campaigns since the 960s, acquiring Kołobrzeg[89]

- 1000: Congress of Gniezno constitutes Reinbern's Bishopric of Kołobrzeg[90]

- 1005: Pomerania regains independence[citation needed], bishopric dissolved[10][need quotation to verify][12][need quotation to verify][14][need quotation to verify][15][need quotation to verify][76][need quotation to verify]

- 1046: A Siemomysł, called to Merseburg by king Henry III to conclude a peace settlement, is the first documented duke of Pomerania, though the extent and location of his realm is unknown.[7][91]

- 1056/57: The Lutici alliance breaks apart in a civil war,[9] subsequent Obodrite eastward expansion.[83]

- 1067/68 and 1069: Saxon expeditions raid and destroy Rethra, the main Liutician stronghold and temple.[84]

- 1093: Lutici,[85] Pomeranians[85] and Rani[85] have to pay tribute to Obodrite prince Henry.[86]

High Middle Ages

[edit]

In the early 12th century, Obodrite, Polish, Saxon, and Danish conquests resulted in vassalage and Christianization of the formerly pagan and independent Pomeranian tribes.[16][92][93][94] Local dynasties ruled the Principality of Rügen (House of Wizlaw), the Duchy of Pomerania (House of Pomerania), the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp (Ratiboride branch of the House of Pomerania), and the duchies in Pomerelia (Samborides).[92] Monasteries were founded at Grobe, Kolbatz, Gramzow, and Belbuck which supported Pomerania's Christianization and advanced German settlements.[95]

The dukes of Pomerania expanded their realm into Circipania and Uckermark to the Southwest, and competed with the Margraviate of Brandenburg for territory and formal overlordship over their duchies. Pomerania-Demmin lost most of her territory and was integrated into Pomerania-Stettin in the mid-13th century. When the Ratiborides died out in 1223, competition arose for the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp,[96] which changed hands numerous times.

Throughout the High Middle Ages, a large influx of German settlers and the introduction of German law, custom, and Low German language turned the area west of the Oder into a German one (Ostsiedlung). The Wends, who during the Early Middle Ages had belonged to the Slavic Rani, Lutician and Pomeranian tribes, were assimilated by the German Pomeranians. To the east of the Oder this development occurred later; in the area from Stettin eastward, the number of German settlers in the 12th century was still insignificant.[citation needed] The Kashubians descendants of Slavic Pomeranians, dominated many rural areas in Pomerelia.[citation needed]

The conversion of Pomerania to Christianity was achieved primarily by the missionary efforts of Absalon and Otto von Bamberg, by the foundation of numerous monasteries, and by the assimilatory power of the Christian settlers. A Pomeranian diocese was set up in Wolin, the see was later moved to Cammin.[97]

Timeline 1100–1300

[edit]

- 1100: Unsuccessful siege of the Obodrite capital Liubice by the Rani[98]

- 1102–1121/2: Bolesław III Wrymouth conquers Pomerania east of the Oder and the burghs of Szczecin (Stettin) and Wolin (Wollin, Jumne);[99] first known dukes of the House of Pomerania (West) and Samborides (East)[18]

- 1120s: Wartislaw I of the House of Pomerania expands his duchy westward and incorporates Liutician territory including the County of Gützkow, Wolgast, Circipania and Uckermark[100]

- 1123–1125: Obodrite prince Henry subdues the Rani[85] Wartislaw accepted the superiority of the Holy Roman Emperor and, with the exception of the newly won territories, also the superiority of the Polish duke.[101]

- 1124/28: Otto of Bamberg's mission results in the Conversion of Pomerania to Christianity[16][93][102][103][104][105]

- 1128: Rani forces assault and destroy Obodrite Liubice[98][106]

- 1135: Boleslaw accepts the superiority of Holy Roman Emperor Lothair, who in turn grants him Pomerania as a fief, including the Oder area and the principality of Rügen which had not been subjugated yet.[20]

- since 1138: Boleslaw dies, the Griffin duchy regains independence from the Piasts[101][107][need quotation to verify]

- 1140: Diocese of Cammin set up, centred at Wolin and subordinate directly to the Holy See[18]

- 1147: Wendish Crusade mounted by dukes and bishops of the Holy Roman Empire, Danish and Polish participation[20]

- 1155: Partition of the Duchy of Pomerania into Pomerania-Demmin and Pomerania-Stettin[108]

- 1164: Battle of Verchen, House of Pomerania becomes vassals of Henry the Lion's Duchy of Saxony[109][110]

- 1168: Danish expedition led by Roskilde archbishop Absalon takes the Principality of Rügen, resulting in the conversion of the Rani who became Danish vassals[18][20][111]

- ~1170: first German settlements[112]

- 1170s and early 1180s: various encounters between Pomeranians and Danes. Danes raid Circipania and Wolin.

- 1181: House of Pomerania becomes vassal of Barbarossa's Holy Roman Empire[111][113][114]

- 1184: Pomeranian navy repelled and destroyed by the Danes in the Bay of Greifswald[114]

- 1186: All Pomerania under Danish control, Holy Roman Empire temporarily renounces her claims[114][115]

- since 1220: Ostsiedlung. Existing towns adopt German town law based on Lübeck law, Magdeburg law or Kulm law), new ones are established with these laws, woods and swamps are cleared and settled, existing villages are expanded and reorganized, new villages are founded.[22]

- 1227: Denmark is defeated in the Battle of Bornhöved, Danish unable to keep Pomerania thereafter[114][115]

- 1231: Upon coming of age, the Margraves of Brandenburg Johann I and Otto III receive Pomerania from the Roman-German Emperor Frederick II at Ravenna.

- 1236: Treaty of Kremmen: Pomerania-Demmin loses most of her territory to the Margraviate of Brandenburg

- 1250: Treaty of Landin: Pomerania-Stettin able to incorporate remainder of Pomerania-Stettin, but loses Uckermark

- since 1250: southern parts of Pomerania lost to Brandenburg and become northern Neumark[116]

- 1223–1283: House of Pomerania, the margraves of Brandenburg, the princes of Rügen and the Pomerelian Samborides compete for the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp after the Ratiborides branch of the House of Pomerania became extinct[96]

- 1283–1294: Lands of Schlawe and Stolp part of Pomerelia[96]

- 1295: Duchy of Pomerania partitioned in Pomerania-Wolgast and Pomerania-Stettin[117]

Late Middle Ages

[edit]

The towns of the Hanseatic League were acting as quasi autonomous political and military entities.[118][119] The Duchy of Pomerania gained the Principality of Rügen after two wars with Mecklenburg,[23] the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp[120] and the Lauenburg and Bütow Land.[24] Pomerelia was integrated into the Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights after the Teutonic takeover of Danzig in 1308, and became a part of Royal Prussia in 1466.

The Duchy of Pomerania was internally fragmented into Pomerania-Wolgast, -Stettin, -Barth, and -Stolp.[121][122] The dukes were in continuous warfare with the Margraviate of Brandenburg due to Uckermark and Neumark border disputes and disputes over formal overlordship of Pomerania.[123]

In 1478, the duchy was reunited under the rule of Bogislaw X, when most of the other dukes had died of the plague.[124][125]

Timeline 1300–1500

[edit]

- 1294–1308: Margraviate of Brandenburg and Poland compete for Pomerelia after the Samborides died out.[126]

- 1308: Teutonic take-over of Danzig (Gdańsk)

- 1309: Treaty of Soldin (Myślibórz) – The Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights purchases the Margraviate of Brandenburg's disputed claim to Pomerelia after conquering the territory.

- 1317–47: Duchy of Pomerania takes the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp as a Brandenburgian fief; in 1317, local Swenzones dynasty continues to rule; full incorporation into Pomerania-Wolgast in 1347.[127]

- 1325–1356: Rügen War of Succession with Mecklenburg. Pomerania-Wolgast incorporates the Principality of Rügen.[23]

- 1361–1368: two wars of the Hanseatic League with Denmark result in the Treaty of Stralsund (1370), the high-water mark of Hanseatic power.[128][129][130]

- 1368/72: Pomerania-Wolgast partitioned into P.-Wolgast and P.-Stolp[122][131][132]

- 1376–1394: Pomerania-Wolgast partitioned into P.-Wolgast and P.-Barth[122][131]

- 1397: Eric of Pomerania-Stolp becomes king of the Kalmar Union.[133]

- 1410: Gdańsk (Danzig) sides with Poland during the Polish war against the Teutonic Order.[134]

- 1425: Pomerania-Wolgast again partitioned into P.-Wolgast and P.-Barth.[135]

- 1448: First Peace of Prenzlau ends a war between Pomerania-Stettin and Brandenburg.

- 1455: Lauenburg and Bütow Land granted to the House of Pomerania.[24]

- 1456: University of Greifswald founded.[136]

- 1464: death of Otto III of Pomerania-Stettin, causes war for succession between Pomerania-Wolgast and Brandenburg.[137]

- 1466: Treaty of Soldin: Duchy of Pomerania becomes a nominal fief of the Electorate of Brandenburg. Implementation failed, war flares up again.[138]

- 1466: Second Peace of Thorn: the Teutonic Order cedes Pomerelia to the Polish Crown as part of what is later called Royal Prussia, Lauenburg and Bütow Land confirmed to the Duchy of Pomerania.[24]

- 1472/9: Second Peace of Prenzlau ends a war between Pomerania-Stettin and Brandenburg.[124][139]

- 1478: Bogislaw X becomes sole ruler of the Duchy of Pomerania since all other male Griffins deceased, most of a plague epidemic.[124][140]

- 1493: Treaty of Pyritz ends the armed Brandenburg-Pomeranian conflicts.

Early Modern Age

[edit]

Throughout this time, Pomerelia was within Royal Prussia, a part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with considerable autonomy. In the late 18th century, it became a part of Prussia.

The Duchy of Pomerania was fragmented into Pomerania-Stettin (Farther Pomerania) and Pomerania-Wolgast (Western Pomerania) in 1532,[18][141] underwent Protestant Reformation in 1534,[26][27][25] and was even further fragmented in 1569,[142] while all parts stayed part of the Empire's Upper Saxon Circle. In 1627, the Thirty Years' War reached the duchy.[143] Since the Treaty of Stettin (1630), it was under Swedish control.[143][144] In the midst of the war, the last duke Bogislaw XIV died without an issue. Garrison, plunder, numerous battles, famine and diseases left two thirds of the population dead and most of the country ravaged.[145][146] In the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the Swedish Empire and Brandenburg-Prussia agreed on a partition of the duchy, which came into effect after the Treaty of Stettin (1653). Western Pomerania became Swedish Pomerania, a Swedish dominion, while Farther Pomerania became a Brandenburg-Prussian province. Swedish Pomerania stayed part of the Holy Roman Empire and the Swedish king became Prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

A series of wars affected Pomerania in the following centuries. As a consequence, most of the formerly free peasants became serfs of the nobles.[147] Brandenburg-Prussia was able to integrate southern Swedish Pomerania into her Pomeranian province during the Great Northern War, which was confirmed in the Treaty of Stockholm in 1720.[30] In the 18th century, Prussia rebuild and colonised her war-torn Pomeranian province.[148]

Timeline 1500–1806

[edit]

- 1520s: Protestant Reformation[27][25]

- 1529: Treaty of Grimnitz settles the Brandenburg-Pomeranian conflict between the houses of Pomerania and Hohenzollern.

- 1532: Partition of the Duchy of Pomerania into P.-Wolgast (Western Pomerania) and P.-Stettin (Farther Pomerania)[18][25]

- 1534: Protestantism officially adopted in the Duchy of Pomerania by the Landtag.[26][27][25]

- 1569: Pomerania-Barth split off Pomerania-Wolgast, Pomerania-Rügenwalde split off Pomerania-Stettin.[142]

- 1627: Thirty Years' War reaches Pomerania, Duchy of Pomerania surrendered to the imperial army in the Capitulation of Franzburg.[143]

- 1628: Battle of Stralsund (1628), Battle of Wolgast

- 1630: Treaty of Stettin (1630): Duchy of Pomerania allied to and occupied by the Swedish Empire.[143]

- 1635–1644: Imperial troops several times occupy Pomerania.[150]

- 1637: last Duke of Pomerania deceased, districts of Lauenburg and Butow Land (Lębork and Bytow) had returned to Polish rule.

- 1644: Battle of Colberger Heide

- 1648: Peace of Westphalia – partition of the Duchy of Pomerania: Western Pomerania becomes Swedish Pomerania, Farther Pomerania granted to Brandenburg-Prussia. Two thirds of the population dead, most of the duchy ravaged.

- 1653: Treaty of Stettin (1653): Swedes withdraw from Farther Pomerania, Brandenburg sets up Province of Pomerania there.

- 1656–1660: Second Northern War – all of Pomerania affected by campaigns of Sweden, Brandenburg and Poland.[151]

- 1656: Treaty of Labiau – Sweden allies with Prussia.

- 1657: Treaty of Wehlau, confirmed by subsequent Treaty of Bromberg – Prussian rights in Pomerania assured by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- 1658: Sweden and Prussia break their alliance and battle each other in Swedish Pomerania.[152]

- 1660: Peace of Oliva restores the conditions before the war to Pomerania.

- 1675–1679: Scanian War between Sweden, Prussia and Denmark affects Swedish Pomerania and the Prussian province of Pomerania.[153] Battle of Stralsund (1678).

- 1679: Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye restores pre-war conditions in Pomerania.

- 1700–1721: Great Northern War between Prussia, Sweden and Denmark;[30] plague in Pomerania

- 1715: Battle of Stralsund (1715); Denmark and Prussia conquer Swedish Pomerania.[30]

- 1720: Treaty of Frederiksborg and Treaty of Stockholm – Southern Swedish Pomerania becomes part of the Kingdom of Prussia and is incorporated into the Province of Pomerania.[30]

- 1757–1762: Seven Years' War reaches the Swedish and Prussian Pomerania, Swedish, Russian and Prussian forces ravage the duchy.[154] Kolberg was the subject of sieges in 1759, 1760 and 1761.

- 1772–1793: Partitions of Poland – Pomerelia is annexed into Prussia's province of West Prussia, plans to Germanize the province and discrimination of Polish population.[citation needed]

Modern Age

[edit]

From the Napoleonic Wars to World War I, Pomerania was administered by the Kingdom of Prussia as the Province of Pomerania (Western and Farther Pomerania) and West Prussia (Pomerelia).

The Province of Pomerania was created from the Province of Pomerania (1653–1815) (Farther Pomerania and southern Vorpommern) and Swedish Pomerania (northern Vorpommern), and the districts of Schivelbein and Dramburg, formerly belonging to the Neumark.[32] While in the Kingdom of Prussia, the province was heavily influenced by the reforms of Karl August von Hardenberg[155] and Otto von Bismarck.[156] The Industrial Revolution had an impact primarily on the Stettin area and the infrastructure, while most of the province retained a rural and agricultural character.[157] Since 1850, the net migration rate was negative, Pomeranians emigrated primarily to Berlin, the West German industrial regions and overseas.[158] Also, more than 100,000 Kashubian Poles emigrated from Pomerania between 1855 and 1900, for economic and social reasons, in what is called the Kashubian diaspora.[159] In areas where ethnically Polish population lived along with ethnic Germans a virtual apartheid existed (in Prussian Pomerania this was mostly the Lauenburg and Bütow Land), with bans on Kashubian or Polish language and religious discrimination, besides attempts to colonize areas of prevailingly ethnically Polish population with ethnic Germans[160] the Prussian Settlement Commission, established in 1886 and restricted to act in Posen and West Prussia provinces only, parcelled acquired noble latifundia into 21,727 homesteads of an average of 13 to 15 hectares, introducing 154,000 ethnic German colonists before World War I, which were all outside of Prussian Pomerania, but are also located in areas today denominated as Pomerania in Polish geography.[161] This was surpassed after 1892 by efforts of new private initiatives by minority of ethnically Polish Germans, but a majority in wide parts of Posen and West Prussia province, who founded the Prussian banks Bank Ziemski, Bank Społek Zarobkowych (cooperative central clearing bank) and land acquisition cooperatives (spółki ziemskie)[162] which collected private funds and succeeded to buy more latifundia from defaulted owners and settle more ethnically Polish Germans as farmers on the parcelled land than their governmentally funded counter-party. A big success of the Prussian activists for the Polish nation.

After the First World War, under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Pomeranian Voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic was established from the bulk of West Prussia. Poland became a democracy and introduced the women's right to vote in 1918.[163]

The German minority in the newly created Polish Republic moved to Germany in large numbers, mostly of their own free will and due to their economic situation.[164] For use as a harbor within the Polish Corridor, Poland built a large Baltic port at the site of the former village Gdynia. Also under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Danzig (Gdańsk) area became the Free City of Danzig, a city-state under League of Nations protection.

After the Kaiser's abdication, democracy and the women's right to vote were introduced to the Weimar Republic and through it to the Free State of Prussia and the Province of Pomerania of which it was a part.[165] The economic situation worsened due to the consequences of World War I and the worldwide recession.[166] As in the Kingdom of Prussia before, Pomerania was a stronghold of the nationalistic and anti-Semitic[167] German National People's Party.[168] Between 1920 and 1932, the government of the state of Prussia was led by the Social Democrats, with Otto Braun Prussian minister-president almost continuously during this time.

Timeline 1806–1933

[edit]

- 1806–1813: Napoleonic Wars in Pomerania[170]

- 1806: Gustavia constructed.[171]

- 1806/7: French forces take Province of Pomerania except for Kolberg.[170]

- 1807: Battle of Stralsund and Siege of Kolberg

- 1807: Peace of Tilsit, Prussia surrenders.[170]

- 1808: French troops withdraw from the Province of Pomerania.[170]

- 1809: Ferdinand von Schill killed in the Battle of Stralsund (1809)

- 1812: French forces invade Swedish Pomerania and again occupy the Prussian Province of Pomerania.[170]

- 1812: Convention of Tauroggen, Pomeranian corps led by Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg turns against France.[170]

- 1813: Mobilization in the Prussian parts of Pomerania against France, Russian forces occupy the Prussian Province of Pomerania, French forces withdraw.[170]

- 1815: Congress of Vienna: Prussia gains Swedish Pomerania.

- 1815: reorganization of the Province of Pomerania: Swedish Pomerania and the Dramburg and Schivelbein counties merged into the former province, administrative reforms implemented.[32]

- 1815: With the Kingdom of Prussia, the Province of Pomerania and West Prussia join the German Confederation (1815–1866).

- 1829–1878: West Prussia merged with East Prussia into Province of Prussia.

- since 1840: introduction of a railway system[157]

- 1839: Marcin Dunin, archbishop of Poznań and Gniezno, primate of Poland, is imprisoned by Prussian authorities in Kołobrzeg.[172]

- 1846: 100 Kashubians led by Florian Ceynowa fail in an attempt to take the Prussian garrison Preußisch Stargard (Starograd Gdański) as part of anti-Prussian uprising.[173]

- 1848: Poles stage an uprising in southern Pomerelia, engage in fights Tuchola Forest against Prussian soldiers.

- 1862: Oder and Swine deepened, heavy industry settled in Stettin.[174]

- 1867: with the Kingdom of Prussia, the Province of Pomerania and Pomerelia within the Province of Prussia join the North German Confederation (1867–1871).

- since 1870: considerable tourism at the Baltic coast, former fishing villages are turned into seaside resorts[175]

- 1871: with the Kingdom of Prussia, the Province of Pomerania (and Pomerelia within the Province of Prussia) join the German Empire (1871–1918).

- 1872, 1875, 1891: administrative reforms[176]

- 1878: West Prussia reestablished.

- 1918: November Revolution after World War I, "soldiers' and workers' councils" take over most Pomeranian towns.[177]

- 1919: Treaty of Versailles: West Prussia dissolved, Pomerelia becomes part of the Second Polish Republic as part of Pomeranian Voivodeship, Danzig (Gdańsk) made Free City of Danzig.

- 1919: Counter-revolution, Freikorps active in German Pomerania.[178]

- 1920: new democratic constitution of the Free State of Prussia now within the Weimar Republic[179]

- 1920: Pomeranian Freikorps participate in the Kapp Putsch.[178]

- since 1920: Poles construct Gdynia as their port city in Pomerelia (then the Pomeranian Voivodeship) and connect it to Upper Silesian industry by the Polish Coal Trunk-Line.

- 1920s: economic recession in the German parts of Pomerania[166]

- 1932: Regierungsbezirk Stralsund merged into Regierungsbezirk Stettin.

Nazi era

[edit]

In 1933, the Province of Pomerania, like all of Germany, came under control of the Nazi regime. During the following years, the Nazis led by Gauleiter Franz Schwede-Coburg manifested their power by Gleichschaltung and repression of their opponents.[180] Pomerelia then formed the Polish Corridor of the Second Polish Republic. Concerning Pomerania, Nazi diplomacy aimed at incorporation of the Free City of Danzig and a transit route through the corridor, which was rejected by the Polish government.[181]

In 1939, the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland. Inhabitants of the region from all ethnic backgrounds were subject to numerous atrocities by Nazi Germany forces, of which the most affected were Polish and Jewish civilians.[182][183][184] Pomerelia was made part of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia. The Nazis set up concentration camps, ethnically cleansed Poles and Jews, and systematically exterminated Poles, Roma and the Jews. In Pomerania Albert Forster was directly responsible for extermination of non-Germans in Danzig-West Prussia. He personally believed in the need to engage in genocide of Poles and stated that "We have to exterminate this nation, starting from the cradle",[185][186][187][verification needed] and declared that Poles and Jews were not human.[188][189]

Around 70 camps were set up for Polish populations in Pomerania where they were subjected to murder, torture and in case of women and girls, rape before executions.[190][191][verification needed] Between 10 and 15 September Forster organised a meeting of top Nazi officials in his region and ordered the immediate removal of all "dangerous" Poles, all Jews and Polish clergy[192] In some cases Forster ordered executions himself.[193] On 19 October he reprimanded Nazi officials in the city of Grudziadz for not "spilling enough Polish blood".[194]

Timeline 1933–1945

[edit]

- 1933/1934: Enabling Act of 1933 established Nazi rule in the German Province of Pomerania. Gleichschaltung of the Province of Pomerania's administration, institutions and society. Repressions and internment of opponents. Establishment of an SA-led "wild" concentration camp in Stettin.[180]

- 1934: Nazi party headquarters cleansed the Pomeranian Nazi movement of inner-party opponents and exchanged many of the staff.[180]

- 1938: Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia and two Brandenburgian counties merged into the German Province of Pomerania.

- 1938: several counties from Mazovia and Greater Poland were joined to the Polish Pomeranian Voivodship, and her capital was moved from Toruń (Thorn) to Bydgoszcz (Bromberg).

- 1938: Reichskristallnacht: synagogues destroyed, all male Stettin Jews deported to Oranienburg concentration camp for several weeks[195]

- 1939: Nazi Germany invades Poland and annexes Pomerelia and the Free City of Danzig, which were made part of the Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia.

- since 1939: atrocities by German Selbstschutz units and mass murder of the Polish, Kashubian and Jewish population of Danzig-West Prussia at Stutthof concentration camp and in the Mass murders in Piaśnica as part of the Intelligenzaktion in Pomerania

- 1940: deportation of all Jews from German Pomerania, including non-Jewish spouses living in mixed marriages, who had resisted pressure to divorce, to a reservation near Lublin in annexed Poland, where later they were murdered at the extermination camps of Belzec, Majdanek and Sobibor, prepared according to the Nisko Plan; Province of Pomerania declared judenfrei.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42]

- 1945: Soviet capture following the Red Army's East Pomeranian Offensive and the northern theater of the Battle of Berlin, all of Pomerania under Soviet military control.[43] Mass suicides, evacuations, flight, expulsion.[196]

Communist era and recent history

[edit]

In 1945, Pomerania was taken by the Red Army and Polish Armed Forces in the East during the East Pomeranian Offensive and the Battle of Berlin.[197] After the post-war border changes, the German population that had not yet fled was expelled from what in Poland was propagated[198] to be recovered territory.[199][200][201][202] The area east of the Oder and the Szczecin (former Stettin) area was resettled primarily with Poles, who themselves were expelled from Eastern Poland that was re-attached to the USSR. Most of the German cultural heritage of the region was destroyed.[203][204] Most of Western Pomerania stayed with Germany and was merged into Mecklenburg.

With the consolidation of Communism in East Germany and Poland, Pomerania was part of the Eastern Bloc. In the 1980s, the Solidarność movement in Gdańsk (Danzig) and the Wende movement in East Germany forced the Communists out of power and led to the establishment of democracy in both the Polish and German part of Pomerania.[citation needed]

Timeline 1945–present

[edit]- 1945: The Oder-Neisse line becomes the border between Poland and Germany

- 5 July 1945: In addition, Stettin/Szczecin and the mouth of the Oder River were assigned to Poland by the Soviet Union

- 1945–1949: Soviet military officials east of the Oder-Neisse line subsequently hand over administration to Polish officials, Farther Pomerania and the Stettin area reorganized in the Polish Szczecin Voivodeship[44]

- 1945–1950: expulsion of nearly all Germans east of the line[45][46][47][48][49]

- Since 1945: Farther Pomerania and other ethnically cleansed areas dubbed Recovered Territories and resettled primarily with Poles from Central Poland, but also with Poles from former eastern Poland, displaced Poles returning from forced labour in Nazi Germany, Ukrainians displaced by Operation Vistula, and Jews[50][51][52][53]

- since 1945: population in Vorpommern nearly doubles due to influx of expellees.[205]

- 1945/46: land reform in German Pomerania (Bodenreform)

- 1950: Koszalin Voivodeship split off Szczecin Voivodeship.

- 1946–1952: Western Pomerania (Vorpommern) without the Stettin/Szczecin area and Wollin/Wolin was fused with Mecklenburg to form the East German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, later Mecklenburg.[206]

- since 1948: Poland adopts Soviet style economy.

- since 1949: East Germany adopts Soviet style economy.

- since 1950: Western Pomeranian peasants forced to join socialist LPG units[207][208][209]

- 1952: German Pomerania partitioned between newly created administrative units ("Bezirk") Rostock, Neubrandenburg, and Frankfurt.[206]

- 1970: Polish 1970 protests

- 1975: administrative reform of the Szczecin Voivodeship

- 1980: Solidarność movement emerges in Gdańsk and Szczecin, Communist rule in Poland starts to collapse.

- 1986: new port built in Sassnitz-Neu Mukran for the railway ferry between East Germany and the Soviet Union

- 1989: Die Wende movement results in a collapse of Communist rule in East Germany.[citation needed]

- 1990: Western Pomerania becomes part of the newly re-established state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern prior to German reunification.

- 1990: systematical decline of shipbuilding in Polish Pomerania

- 1995: Pomerania euroregion established

- 1999: Koszalin Voivodeship and Szczecin Voivodeship with some parts of neighboring voivodeships Słupsk Voivodeship, Piła Voivodeship, and Gorzów Voivodeship merged into West Pomeranian Voivodeship.[citation needed]

- 2007: the whole Pomerania in Schengen Area.

- 2011: new administrative division of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Der Name Pommern (po more) ist slawischer Herkunft und bedeutet so viel wie „Land am Meer“. Archived 2020-08-19 at the Wayback Machine (Pommersches Landesmuseum, German)

- ^ a b c d e f g RGA 25 (2004), p.422

- ^ a b From the First Humans to the Mesolithic Hunters in the Northern German Lowlands, Current Results and Trends - THOMAS TERBERGER. From: Across the western Baltic, edited by: Keld Møller Hansen & Kristoffer Buck Pedersen, 2006, ISBN 87-983097-5-7, Sydsjællands Museums Publikationer Vol. 1 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.18ff 6

- ^ Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, pp.16ff, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ a b A. W. R. Whittle, Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p.198, ISBN 0-521-44920-0

- ^ a b c d Buchholz (1999), pp.22,23

- ^ a b Herrmann (1985), pp.237ff,244ff

- ^ a b c d e Herrmann (1985), pp.261,345ff

- ^ a b c Piskorski (1999), p.32 :pagan reaction of 1005

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.25: pestagan uprising that also ended the Polish suzerainty in 1005

- ^ a b c A. P. Vlasto, Entry of Slavs Christendom, CUP Archive, 1970, p.129, ISBN 0-521-07459-2: abandoned 1004 - 1005 in face of violent opposition

- ^ a b Nora Berend, Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus' C. 900-1200, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p.293, ISBN 0-521-87616-8, ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2

- ^ a b c David Warner, Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg, Manchester University Press, 2001, p.358, ISBN 0-7190-4926-1, ISBN 978-0-7190-4926-2

- ^ a b c Michael Borgolte, Benjamin Scheller, Polen und Deutschland vor 1000 Jahren: Die Berliner Tagung über den "Akt von Gnesen", Akademie Verlag, 2002, p.282, ISBN 3-05-003749-0, ISBN 978-3-05-003749-3

- ^ a b c Addison (2003), pp.57ff

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.35ff

- ^ a b c d e f g Theologische Realenzyklopädie (1997), pp.40ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.34ff,87,103

- ^ a b c d Piskorski (1999), p.43 ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.77ff

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.45ff

- ^ a b c Buchholz (1999), pp. 115,116

- ^ a b c d Buchholz (1999), p. 186

- ^ a b c d e Buchholz (1999), pp.205-212

- ^ a b c Richard du Moulin Eckart, Geschichte der deutschen Universitäten, Georg Olms Verlag, 1976, pp.111,112, ISBN 3-487-06078-7

- ^ a b c d Theologische Realenzyklopädie (1997), pp.43ff

- ^ Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger (2006). Das Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation: vom Ende des Mittelalters bis 1806. C.H.Beck. p. 10., Joachim Whaley (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 51, 54.

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.263,332,341–343,352–354

- ^ a b c d e Buchholz (1999), pp.341-343

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.363,364

- ^ a b c Buchholz (1999), p.366

- ^ a b Lucie Adelsberger, Arthur Joseph Slavin, Susan H. Ray, Deborah E. Lipstadt, Auschwitz: A Doctor's Story, Northeastern University Press, 1995, ISBN 1-55553-233-0, p.138: February 12/13, 1940

- ^ a b Isaiah Trunk, Jacob Robinson, Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation, U of Nebraska Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8032-9428-X, p.133: February 14, 1940; unheated wagons, elderly and sick suffered most, inhumane treatment

- ^ a b Leni Yahil; Ina Friedman; Haya Galai (1991), The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945, Oxford University Press US, p. 138, ISBN 0-19-504523-8,

February 12/13, 1940, 1,300 Jews of all sexes and ages, extreme cruelty, no food allowed to be taken along, cold, some died during deportation, cold and snow during resettlement, 230 dead by March 12, Lublin reservation chosen in winter, 30,000 Germans resettled before to make room

- ^ a b Martin Gilbert, Eilert Herms, Alexandra Riebe, Geistliche als Retter - auch eine Lehre aus dem Holocaust: Auch eine Lehre aus dem Holocaust, Mohr Siebeck, 2003, ISBN 3-16-148229-8, pp.14 (English) and 15 (German): February 15, 1940, 1000 Jews deported

- ^ a b Jean-Claude Favez; John Fletcher; Beryl Fletcher (1999), The Red Cross and the Holocaust, Cambridge University Press, p. 33, ISBN 0-521-41587-X,

February 12/13, 1,100 Jews deported, 300 died en route

- ^ a b Yad Vashem Studies, Yad ṿa-shem, rashut ha-zikaron la-Shoʼah ṿela-gevurah, Yad Vashem Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, 1996 Notizen: v.12, p.69: 1,200 deported, 250 died during deportation

- ^ a b Nathan Stoltzfus, Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany, Rutgers University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8135-2909-3, p.130: February 11/12 from Stettin, soon thereafter from Schneidemühl, total of 1,260 Jews deported, among the deportees were intermarried non-Jewish women who had refused to divorce, eager Nazi Gauleiter Schwede-Coburg was the first to have his Gau "judenfrei", Eichmann's "RSHA" (Reich Security Main Office) ensured this was an isolated local incident to worried Eppstein of the Central Organization of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland)

- ^ a b John Mendelsohn, Legalizing the Holocaust, the Later Phase, 1939-1943, Garland Pub., 1982, ISBN 0-8240-4876-8, p.131: Stettin Jews' houses were sealed, belongings liquidated, funds to be held in blocked accounts

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.506: Only very few [of the Pomeranian Jews] survived the Nazi era. p.510: Nearly all Jews from Stettin and all the province, about a thousand

- ^ a b Alicia Nitecki, Jack Terry, Jakub's World: A Boy's Story of Loss and Survival in the Holocaust, SUNY Press, 2005, ISBN 0-7914-6407-5, pp.13ff: Stettin Jews to Belzyce in Lublin area, reservation purpose decline of Jews, terror command of Kurt Engels, shocking insights in life circumstances

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.512-515

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), pp.373ff

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), pp.381ff

- ^ a b Tomasz Kamusella in Prauser and Reeds (eds), The Expulsion of the German communities from Eastern Europe, p.28, EUI HEC 2004/1 [1] Archived 2009-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak, Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948, 2001, p.114, ISBN 0-7425-1094-8, ISBN 978-0-7425-1094-4

- ^ a b Gregor Thum, Die fremde Stadt. Breslau nach 1945, 2006, pp.363, ISBN 3-570-55017-6, ISBN 978-3-570-55017-5

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.515

- ^ a b Dierk Hoffmann, Michael Schwartz, Geglückte Integration?, p142

- ^ a b Karl Cordell, Andrzej Antoszewski, Poland and the European Union, 2000, p.168, ISBN 0-415-23885-4

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), p.406

- ^ a b Selwyn Ilan Troen, Benjamin Pinkus, Merkaz le-moreshet Ben-Guryon, Organizing Rescue: National Jewish Solidarity in the Modern Period, pp.283-284, 1992, ISBN 0-7146-3413-1, ISBN 978-0-7146-3413-5

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.16,17

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.17

- ^ a b c d e f Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.16, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), pp.18,19 6

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), p.19 6

- ^ a b c d e f Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, pp.16,17, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ a b c d Piskorski (1999), pp.19,20 6

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.19

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), pp.20,21 6

- ^ a b c d e f Piskorski (1999), p.23 6

- ^ a b Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, pp.18,19, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ a b Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.19, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ a b Piskorski (1999), pp.21ff 6

- ^ a b RGA 23 (2003), p.281

- ^ a b c RGA 23 (2003), p.282

- ^ Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.18, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.26

- ^ a b Harck&Lübke (2001), p.15

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.29ff ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.30

- ^ Harck&Lübke (2001), pp.15ff

- ^ Harck&Lübke (2001), p.27

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.25 : pagan uprising that also ended the Polish suzerainty in 1005

- ^ Jürgen Petersohn, Der südliche Ostseeraum im kirchlich-politischen Kräftespiel des Reichs, Polens und Dänemarks vom 10. bis 13. Jahrhundert: Mission, Kirchenorganisation, Kultpolitik, Böhlau, 1979, p.43, ISBN 3-412-04577-2. 1005/13

- ^ Oskar Eggert, Geschichte Pommerns, Pommerscher Buchversand, 1974: 1005-1009

- ^ Roderich Schmidt, Das historische Pommern: Personen, Orte, Ereignisse, Böhlau, 2007, p.101, ISBN 3-412-27805-X. 1005/13

- ^ Michael Müller-Wille, Rom und Byzanz im Norden: Mission und Glaubenswechsel im Ostseeraum während des 8.-14. Jahrhunderts: internationale Fachkonferenz der deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Verbindung mit der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz: Kiel, 18.-25. 9. 1994, 1997, p.105, ISBN 3-515-07498-8, ISBN 978-3-515-07498-8

- ^ Herrmann (1985), pp.356ff

- ^ Herrmann (1985), p.359

- ^ a b Herrmann (1985), p.365

- ^ a b Herrmann (1985), p.366

- ^ a b c d e f g Herrmann (1985), p.379

- ^ a b Herrmann (1985), p.367

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.26ff

- ^ Leyser, Karl. "Henry I and the Beginnings of the Saxon Empire." The English Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 326. (January, 1968), pp 1–32.

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.32

- ^ Michael Borgolte, Benjamin Scheller, Polen und Deutschland vor 1000 Jahren: Die Berliner Tagung über den "Akt von Gnesen", Akademie Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-05-003749-0, ISBN 978-3-05-003749-3

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.33

- ^ a b Theologische Realenzyklopädie (1997), p.40

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.25

- ^ Herrmann (1985), pp.384ff

- ^ Charles Higounet. Die deutsche Ostsiedlung im Mittelalter (in German). p. 145.

- ^ a b c Buchholz (1999), p.87

- ^ W. von Sommerfeld: Geschichte der Germanisierung des Herzogtums Pommern oder Slavien bis zum Ablauf des 13. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig 1896 (printed on demand by Elibron, ISBN 1-4212-3832-2, in German, limited preview).

- ^ a b Herrmann (1985), p.268

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.35

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.40,41

- ^ a b Inachin (2008), p.17

- ^ Addison (2003), pp.59ff

- ^ William Palmer, A Compendioius Ecclesiastical History from the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Kessinger Publishing, 2005, pp.107ff, ISBN 1-4179-8323-X

- ^ Herrmann (1985), pp.402ff

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.36ff

- ^ Herrmann (1985), p.381

- ^ Herrmann (1985), pp.386

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.41,42

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.30,34

- ^ Piskorski (1999), pp.43,44

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.34

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.77

- ^ "Pommern History". Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ^ a b c d Piskorski (1999), p.44

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.34,35

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.89

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.104-105

- ^ Craig J. Calhoun, Joseph Gerteis, James Moody, Steven Pfaff, Indermohan Virk, Contemporary Sociological Theory, Blackwell Publishing, 2002, pp.157,158 ISBN 0-631-21350-3, ISBN 978-0-631-21350-5

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.128-154,178-180

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp. 106

- ^ Hartmut Boockmann, Die Anfänge der ständischen Vertretungen in Preussen und seinen Nachbarländern, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1992, pp.131,132, ISBN 3-486-55840-4

- ^ a b c Buchholz (1999), pp.143,146,147

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp. 160-166,180ff

- ^ a b c Bogislaw X in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie[permanent dead link]

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.189

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.103

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.105

- ^ Phillip Pulsiano, Kirsten Wolf, Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, 1993, p.265, ISBN 0-8240-4787-7

- ^ Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer, The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, p.265, ISBN 0-395-65237-5

- ^ Angus MacKay, David Ditchburn, Atlas of Medieval Europe, Routledge, 1997, p.171, ISBN 0-415-01923-0

- ^ a b Hartmut Boockmann, Die Anfänge der ständischen Vertretungen in Preussen und seinen Nachbarländern, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1992, pp.132,133, ISBN 3-486-55840-4

- ^ Piskorski (1999), p.97

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.154-158

- ^ Edmund Cieślak Historia Gdańska, t. I, Wydawnictwo Morskie, Gdańsk 1978, page 479

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.154

- ^ Richard du Moulin Eckart, Geschichte der deutschen Universitäten, Georg Olms Verlag, 1976, p.109, ISBN 3-487-06078-7

- ^ Heitz (1995), pp.193,194

- ^ Heitz (1995), p.195

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.190

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.181ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.205-220

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.207

- ^ a b c d Buchholz (1999), p.233

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.235,236

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.263

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.332

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.264ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.332,347,354

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.263,332

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.235,236,263

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.273ff,317ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.318

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.318,319

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.352–354

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.393ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.420ff

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.412,413,464ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.400ff

- ^ "The Kashubian Emigration – Bambenek.org". bambenek.org. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ^ A history of modern Germany, 1800-2000 Martin Kitchen Wiley-Blackwel 2006, page 130)

- ^ Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 page 461

- ^ "Rozwój polskiej bankowości w Poznaniu rozpoczął się w 2. połowie XIX wieku", on: POZnan*, retrieved on 5 August 2021.

- ^ Poland became a democracy and introduced women's right to vote God's Playground: A History of Poland, By Norman Davies, Columbia University Press, 1982, p. 302

- ^ Richard Blanke, Orphans of Versailles, p32ff, 1993

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.472ff

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), pp.443ff,481ff

- ^ Adolf Hitler: a biographical companion David Nicholls page 178 November 1, 2000 The main nationalist party the German National People's Party DNVP was divided between reactionary conservative monarchists, who wished to turn the clock back to the pre-1918 Kaisereich, and more radical volkisch and anti-semitic elements. It also inherited the support of old Pan-German League, whose nationalism rested on belief in the inherent superiority of the German people

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.377ff,439ff,491ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.464

- ^ a b c d e f g Buchholz (1999), pp.363,364

- ^ Asmus

- ^ Na stolicy prymasowskiej w Gnieźnie i w Poznaniu: szkice o prymasach Polski w okresie niewoli narodowej i w II Rzeczypospolitej : praca zbiorowa Feliks Lenort Księgarnia Św. Wojciecha, 1984, pages 139-146

- ^ Ireneus Lakowski, Das Behinderten-Bildungswesen im Preussischen Osten: Ost-West-Gefälle, Germanisierung und das Wirken des Pädagogen Joseph Radomski, LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2001, pp.25ff, ISBN 3-8258-5261-X

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.413ff,447ff

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.465

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.420ff,453

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.471

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.472

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.443ff,472ff

- ^ a b c Buchholz (1999), pp.500ff,509ff ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- ^ Joachim C. Fest, Hitler, Harcourt Trade, 2002, pp.575-577, ISBN 0-15-602754-2 [2][permanent dead link]

- ^ Max Kerner, Verband der Historiker und Historikerinnen Deutschlands, Eine Welt, eine Geschichte?: 43. Deutscher Historikertag in Aachen, 26. Bis 29. September 2000: Berichtsband, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2000, p.226, ISBN 3-486-56614-8 [3]

- ^ Bernhard Chiari, Jerzy Kochanowski, Germany Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt, Die polnische Heimatarmee: Geschichte und Mythos der Armia Krajowa seit dem zweiten Weltkrieg, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, pp.59,60, ISBN 3-486-56715-2 [4]

- ^ Detlef Brandes, Der Weg zur Vertreibung 1938-1945: Pläne und Entscheidungen zum"transfer" der Deutschen aus der Tschechoslowakei und aus Polen, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2005, p.62, ISBN 3-486-56731-4 [5]

- ^ Eugenia Bozena Klodecka-Kaczynska, Michal Ziólkowski (1 Jan 2003), Bylem numerem: swiadectwa z Auschwitz, page 14. Wydawn. Sióstr Loretanek.

- ^ Barbara Bojarska (1989), Piasnica, miejsce martyrologii i pamieci: z badan nad zbrodniami hilerowskimi na Pomorzu. Page 20. "Szczególny niepokój wywolala wsród mieszkanców jego wyrazna zapowiedz akcji zaglady Polaków, streszczajaca sie chocby w tym jednym zdaniu: Musimy ten naród wytepic od kolyski poczawszy."

- ^ Dieter Schenk (2002), Albert Forster: gdanski namiestnik Hitlera : zbrodnie hitlerowskie w Gdansku i Prusach Zachodnich, POLNORD - Gdansk, page 388.

- ^ Danuta Drywa (2001), Zaglada Zydów w obozie koncentracyjnym Stutthof Muzeum Stutthof w Sztutowie. "Polityke eksterminacyjna na Pomorzu Gdanskim mial bezposrednio realizowac gauleiter Okregu Gdansk-Prusy Albert Forster."

- ^ Dieter Schenk (2002), Albert Forster: gdanski namiestnik Hitlera, page 221. "...postawe Forstera, który nie poczuwal sie do jakiejkolwiek winy, zwlaszcza w przypadkach, gdy chodzilo - w jego mniemaniu - o „podludzi" w rodzaju prostytutek, Polaków i Zydów, o których zazwyczaj mówiono element".

- ^ Maria Wardzynska: Byl rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczenstwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion. Warszawa: Instytut Pamieci Narodowej, 2009. ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8 page 17

- ^ Barbara Bojarska: Eksterminacja inteligencji polskiej na Pomorzu Gdanskim, page 67.

- ^ Dieter Schenk (2002): Albert Forster. Gdanski namiestnik Hitlera. Gdansk: Wydawnictwo Oskar. ISBN 83-86181-83-4, pages 212-213.

- ^ Dieter Schenk (2002): Albert Forster. Gdanski namiestnik Hitlera. Gdansk: Wydawnictwo Oskar. ISBN 83-86181-83-4, page 215.

- ^ Barbara Bojarska: Eksterminacja inteligencji polskiej na Pomorzu Gdanskim, page 66.

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.510

- ^ Jankowiak, Stanislaw (2001). "Cleansing" Poland of Germans: the Province of Pomerania 1945-1949. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 87. ISBN 9780742510944. in Philipp Ther: Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.511-515

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella and Terry Sullivan in Karl Cordell, Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe, 1999, p.169: "[the term "recovered territories" was] christened so by the Polish communist-cum-nationalist propaganda", ISBN 0-415-17312-4, ISBN 978-0-415-17312-4

- ^ Geoffrey Hosking, George Schopflin, Myths and Nationhood, 1997, p.153, ISBN 0-415-91974-6, ISBN 978-0-415-91974-6

- ^ Joanna B. Michlic, Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present, 2006, pp.207-208, ISBN 0-8032-3240-3, ISBN 978-0-8032-3240-2

- ^ Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes, 2005, pp.381ff, ISBN 0-19-925340-4, ISBN 978-0-19-925340-1

- ^ Jan Kubik, The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland, 1994, pp.64-65, ISBN 0-271-01084-3, ISBN 978-0-271-01084-7

- ^ Dan Diner, Raphael Gross, Yfaat Weiss, Jüdische Geschichte als allgemeine Geschichte, p.164

- ^ Gregor Thum, Die fremde Stadt. Breslau nach 1945, 2006, p.344, ISBN 3-570-55017-6, ISBN 978-3-570-55017-5

- ^ Buchholz (1999), pp.515ff

- ^ a b Buchholz (1999), p.519

- ^ Heinrich-Christian Kuhn, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in Der Bürger im Staat, "Die Bundesländer", Heft 1/2, 1999

- ^ Beatrice Vierneisel, Fremde im Land: Aspekte zur kulturellen Integration von Umsiedlern in Mecklenburg und Vorpommern 1945 bis 1953, 2006, p.13, ISBN 3-8309-1762-7, ISBN 978-3-8309-1762-5

- ^ Buchholz (1999), p.521

Bibliography

[edit]- Addison, James Thayer (2003). Medieval Missionary: A Study of the Conversion of Northern Europe Ad 500 to 1300. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7567-7.

- Asmus, Ivo. "Gustavia - Ein schwedisches Hafen- und Stadtprojekt für Mönchgut" (in German and Swedish). rügen.de. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko, eds. (2003). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde Band 23. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017535-5.

- Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko, eds. (2004). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde Band 25. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017733-1.

- Buchholz, Werner, ed. (2002). Pommern (in German). Siedler. ISBN 3-88680-780-0.

- Harck, Ole; Lübke, Christian (2001). Zwischen Reric und Bornhöved: Die Beziehungen zwischen den Dänen und ihren slawischen Nachbarn vom 9. Bis ins 13. Jahrhundert: Beiträge einer internationalen Konferenz, Leipzig, 4.-6. Dezember 1997 (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-07671-9.

- Heitz, Gerhard; Rischer, Henning (1995). Geschichte in Daten. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German). Münster-Berlin: Koehler&Amelang. ISBN 3-7338-0195-4.

- Herrmann, Joachim (1985). Die Slawen in Deutschland (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 3-515-07671-9.

- Inachin, Kyra (2008). Die Geschichte Pommerns. Rostock: Hinstorff. ISBN 978-3-356-01044-2.

- Krause, Gerhard; Balz, Horst Robert (1997). Müller, Gerhard (ed.). Theologische Realenzyklopädie. De Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015435-8.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten (in German). Zamek Ksiazat Pomorskich. ISBN 83-906184-8-6. OCLC 43087092.

Further reading

[edit]English:

- Boehlke, LeRoy, Pomerania – Its People and Its History, Pommerscher Verein Freistadt, Germantown, WI, U.S.A., 1983.

German and Polish:

- Jan Maria Piskorski et al. (Werner Buchholz, Jörg Hackmann, Alina Hutnikiewicz, Norbert Kersken, Hans-Werner Rautenberg, Wlodzimierz Stepinski, Zygmunt Szultka, Bogdan Wachowiak, Edward Wlodarczyk), Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, Zamek Ksiazat Pomorskich, 1999, ISBN 83-910291-0-7. This book is a co-edition of several German and Polish experts on Pomeranian history and covers the history of Pomerania, except for Pomerelia, from the earliest appearance of humans in the area until the end of the second millennium. It is also available in a Polish version (Pomorze poprzez wieki).

Polish:

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. I (to 1466), parts 1–2, Poznań 1969

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. II (1466–1815), parts 1–2, Poznań 1976

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. III (1815–1850), parts 1–3, Poznań

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. IV (1850–1918), part 1, Toruń 2003

- B. Śliwiński, "Poczet książąt gdańskich", Gdańsk 1997

German:

- Werner Buchholz et al., Pommern, Siedler, 1999/2002, ISBN 3-88680-780-0, 576 pages; this book is part of the Deutsche Geschichte im Osten Europas series and covers the history of the Duchy of Pomerania and Province of Pomerania from the 12th century to 1945, and Western Pomerania after 1945.

- Oskar Eggert, Geschichte Pommerns, Hamburg 1974, OCLC 2187161; this book treats the history of Pomerania from pre-historic times up to about 1500.

KSF

KSF