History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 47 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 47 min

The history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has three main periods, described generally as:[1][2][3]

- the early history during the lifetime of Joseph Smith, which is in common with most Latter Day Saint movement churches;

- the "pioneer era" under the leadership of Brigham Young and his 19th-century successors;

- the modern era beginning in the early 20th century as the practice of polygamy was discontinued and many members sought reintegration into U.S. society.

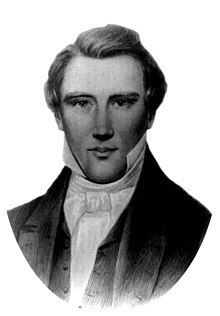

The LDS Church originated in the burned-over district within Western New York.[4] Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, was raised in this region during the Second Great Awakening. Smith gained a small following in the late 1820s as he was dictating the Book of Mormon, which he said was a translation of inscriptions found on a set of golden plates buried near his home in Upstate New York by an Indigenous American prophet named Moroni.

On April 6, 1830, at the home of Peter Whitmer in Fayette, New York, Smith organized the religion's first legal church entity, the Church of Christ,[5] which grew rapidly under Smith's leadership. The main body of the church moved first to Kirtland, Ohio, in the early 1830s, then to Missouri in 1838, where the 1838 Mormon War with other Missouri settlers ensued. On October 27, 1838, Lilburn W. Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, signed Missouri Executive Order 44, which called to expel adherents from the state. Approximately 15,000 Mormons fled to Illinois after their surrender at Far West on November 1, 1838.

After fleeing from Missouri, Smith founded the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, which grew rapidly. When Smith was killed, Nauvoo had a population of about 12,000 people, nearly all members of Smith's church. After his death, a succession crisis ensued and the majority voted to accept the Quorum of the Twelve, led by Brigham Young, as the church's leading body.[6]

After suffering persecution in Illinois, Young left Nauvoo in 1846 and led his followers, the Mormon pioneers, to Salt Lake Valley. The Mormon pioneers then branched out to pioneer a large state called Deseret, establishing colonies that spanned from Canada to Mexico.

Young incorporated the LDS Church as a legal entity and governed his followers as a theocratic leader, assuming both political and religious positions. He also publicized the previously secret practice of plural marriage, a form of polygamy. By 1857, tensions had again escalated between Latter-day Saints and other Americans, largely as a result of the teachings on polygamy and theocracy. During the Utah War, from 1857 to 1858, the United States Army conducted an invasion of Utah, after which Young agreed to be replaced by a non-Mormon territorial Governor, Alfred Cumming.

The church, however, still wielded significant political power in Utah Territory. Even after Young died in 1877, many members continued the practice of polygamy despite opposition by the United States Congress. When tensions with the U.S. government came to a head in 1890, the church officially abandoned the public practice of polygamy in the United States and eventually stopped performing official polygamous marriages altogether after a Second Manifesto in 1904. Eventually, the church adopted a policy of excommunicating members who were found to be practicing polygamy, and today seeks to actively distance itself from polygamist fundamentalist groups.

During the 20th century, the church became an international organization. The church first began engaging with mainstream American culture, and then with international cultures. It engaged especially in Latin American countries by sending out thousands of missionaries. The church began publicly supporting monogamy and the nuclear family, and at times played a role in political matters. One of the official changes to the organization during the modern era was the participation of black members in temple ceremonies, which began in 1978, reversing a policy originally instituted by Young. The church has also gradually changed its temple ceremony. There continue to be periodic changes in the structure and organization of the church.

Early history (1820s to 1846)

[edit]Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, was raised in Western New York during the Second Great Awakening. Smith gained a small following in the late 1820s as he was dictating the Book of Mormon. He stated that the book was a translation of characters from an ancient script called reformed Egyptian that he stated was inscribed on gold plates which had been buried near his residence in western New York by an indigenous American prophet. Smith said he had been given the plates from the angel Moroni.[7]

On April 6, 1830, in western New York,[8] Smith organized the religion's first legal church entity, the Church of Christ. The church rapidly gained a following who viewed Smith as their prophet. In late 1830, Smith envisioned a "City of Zion", a utopian city in Native American lands near Independence, Missouri.[9] In October 1830, he sent his Assistant President, Oliver Cowdery, and others on a mission to the area.[10][unreliable source?] Passing through Kirtland, Ohio, the missionaries converted a congregation of Disciples of Christ led by Sidney Rigdon, and in 1831, Smith decided to temporarily move his followers to Kirtland until lands in the Missouri area could be purchased. In the meantime, the church's headquarters remained in Kirtland from 1831 to 1838 and there the church built its first temple and continued to grow in membership from 680 to 17,881 members.[11]

While the main church body was in Kirtland, many of Smith's followers attempted to establish settlements in Missouri but were met with resistance from other Missourians who believed Mormons were abolitionists or who distrusted their political ambitions.[12] After Smith and other Mormons in Kirtland emigrated to Missouri in 1838, hostilities escalated into the 1838 Mormon War, culminating in adherents being expelled from the state under an Extermination Order signed by Lilburn W. Boggs, the governor of Missouri.

After Missouri, Smith founded the city of Nauvoo, Illinois as the new church headquarters, and served as the city's mayor and leader of the Nauvoo Legion. As church leader, Smith also instituted the then-secret practice of plural marriage and taught a political system he called "theodemocracy", to be led by a Council of Fifty which had secretly and symbolically anointed him king of this millennial theodemocracy.[13]

On June 7, 1844, a newspaper called the Nauvoo Expositor, edited by dissident Mormon William Law, issued a scathing criticism of polygamy and the Nauvoo theocratic government, including a call for church reform based on earlier Mormon principles.[14] In response to the newspaper's publication, Smith and the Nauvoo City Council declared the paper a public nuisance, and ordered the press destroyed.[15] The town marshal carried out the order during the evening of June 10.[16] The destruction of the press led to charges of riot against Smith and other members of the council. After Smith surrendered on the charges, he was also charged with treason against Illinois. While in state custody, he and his brother Hyrum Smith, who was second in line to the church presidency, were killed in a firefight with an angry mob attacking the jail on June 27, 1844.[17]

After Smith's death, a succession crisis ensued. In this crisis a number of church leaders campaigned to lead the church. Most adherents voted on August 8, 1844, to accept the leadership of Brigham Young, the senior apostle. Later, adherents bolstered their succession claims by referring to a March 1844 meeting in which Joseph committed the "keys of the kingdom" to a group of members within the Council of Fifty that included the apostles.[18] In addition, by the end of the 1800s, several of Young's followers had published reminiscences recalling that during Young's August 8 speech, he looked or sounded similar to Joseph Smith, which they attributed to the power of God.[19]

Pioneer era (c. 1846 to c. 1900)

[edit]Migration to Utah and colonization of the West

[edit]

Under the leadership of Brigham Young, church leaders planned to leave Nauvoo, Illinois in April 1846, but amid threats from the state militia, they were forced to cross the Mississippi River in the cold of February. They eventually left the boundaries of the United States to what is now Utah, where they founded Salt Lake City.

The groups that left Illinois for Utah became known as the Mormon pioneers and forged a path to Salt Lake City known as the Mormon Trail. The arrival of the Mormon Pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847, is commemorated by the Utah State holiday Pioneer Day.

Groups of converts from the United States, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere were encouraged to gather in Utah in the following decades. Both the original Mormon migration and subsequent convert migrations resulted in many deaths. Brigham Young organized a great colonization of the American West, with Mormon settlements extending from Canada to Mexico. Notable cities that sprang from early Mormon settlements include San Bernardino, California, Las Vegas, Nevada, and Mesa, Arizona.

Brigham Young's early theocratic leadership

[edit]Following the death of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young stated that the church should be led by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (see succession crisis). Later, after the migration to Utah had begun, Young was sustained as a member of the First Presidency on December 25, 1847,[20] and then as President of the Church on October 8, 1848.[21]

In the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded the area to the United States. As a result, Brigham Young sent emissaries to Washington, D.C. with a proposal to create a vast State of Deseret, of which Young would be the first governor. Instead, Congress created the much smaller Utah Territory in 1850, and Young was appointed governor in 1851. Because of his religious position, Young exercised much more practical control over the affairs of Mormon and non-Mormon settlers than a typical territorial governor of the time.

For most of the 19th century, the LDS Church maintained an ecclesiastical court system parallel to federal courts, and required Mormons to use the system exclusively for civil matters, or face church discipline.[22]

Mormon Reformation

[edit]In 1856–1858, the church underwent what is commonly called the Mormon Reformation.[23] In 1855, a drought struck the flourishing territory. Very little rain fell, and dependable mountain streams ran very low. An infestation of grasshoppers and crickets destroyed whatever crops the Mormons had managed to salvage. During the winter of 1855–56, flour and other basic necessities were very scarce and costly.

In September 1856, as the drought continued, the trials and difficulties led to an explosion of religious fervor. Jedediah M. Grant, a counselor in the First Presidency and a well-known conservative voice in the extended community, preached three days of fiery sermons to the people of Kaysville, Utah territory. He called for repentance and a general recommitment to moral living and religious teachings. 500 people presented themselves for "re-baptism"—a symbol of their determination to reform their lives. The message spread from Kaysville to surrounding Mormon communities. Church leaders traveled around the territory, expressing their concern about signs of spiritual decay and calling for repentance. Members were asked to seal their rededication with re-baptism.

Several sermons Willard Richards and George A. Smith had given earlier in the history of the church had touched on the concept of blood atonement, suggesting that apostates could become so enveloped in sin that the voluntary shedding of their own blood might increase their chances of eternal salvation. On September 21, 1856, while calling for sincere repentance, Brigham Young took the idea further, and stated:

I know that there are transgressors, who, if they knew themselves and the only condition upon which they can obtain forgiveness, would beg of their brethren to shed their blood, that the smoke might ascend to God as an offering to appease the wrath that is kindled against them, and that the law might have its course.

— Journal of Discourses 4:43.

This belief became ingrained in the church's public image during that period and drew widespread ridicule in Eastern newspapers, particularly in connection with the practice of polygamy. The notion faced consistent criticism from numerous Mormons and was ultimately disavowed as an official doctrine by the LDS Church in 1978. Nevertheless, in contemporary times, critics of the church and some popular writers continue to associate a formal doctrine of blood atonement with the Church.[24]

Throughout the winter, special meetings were held and Mormons were urged to adhere to the commandments of God and the practices and precepts of the church. Preaching placed emphasis on the practice of plural marriage, adherence to the Word of Wisdom, attendance at church meetings, and personal prayer. On December 30, 1856, the entire all-Mormon territorial legislature was re-baptized for the remission of their sins, and confirmed under the hands of the Twelve Apostles. As time went on, however, the sermons became intolerant and hysterical.

Utah War and Mountain Meadows massacre

[edit]In 1857–1858, the church was involved in an armed conflict with the U.S. government, now known as the Utah War. The settlers and the United States government battled for hegemony over the culture and government of the territory. Tensions over the Utah War, the murder of Mormon apostle Parley P. Pratt in Arkansas, and threats of violence from the Baker-Fancher wagon train (and possibly other factors),[25] resulted in rogue Mormon settlers in southern Utah massacring a wagon train from Arkansas, known as Mountain Meadows massacre. The result of the Utah War was the succeeding of the governorship of the Utah territory from Brigham Young to Alfred Cumming, an outsider appointed by President James Buchanan.

Brigham Young's later years

[edit]The church had attempted unsuccessfully to institute the United Order numerous times, most recently during the Mormon Reformation. In 1874, Young once again attempted to establish a permanent Order, which he called the "United Order of Enoch" in at least 200 LDS Church-established communities, beginning in St. George, Utah on February 9, 1874.

In Young's Order, producers typically transferred ownership of their property to the Order itself. All members within the order would then collectively partake in the cooperative's net income, often distributed in proportion to the value of the property initially contributed. Occasionally, members received wages for their labor on the shared property. Much like Joseph Smith's United Order, Young's Order had a brief existence. By the time Young died, most of these Orders had faltered. As the 19th century drew to a close, these Orders had effectively become extinct.

Young died in August 1877, but the First Presidency was not reorganized until 1880, when he was succeeded by John Taylor, who in the interim had served as President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Polygamy and the United States "Mormon question"

[edit]For several decades, polygamy was preached as God's law. Brigham Young, the church's second president, had 56 wives during his life;[26][27] many other church leaders were also polygamists.

This early practice of polygamy caused conflict between church members and the broader American society. In 1854, the Republican party referred in its platform to polygamy and slavery as the "twin relics of barbarism." In 1862, the U.S. Congress enacted the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, signed by Abraham Lincoln, which made bigamy a felony in the territories punishable by $500 or five years in prison. The law also permitted the confiscation of church property[28] without compensation. However, this law was not enforced by the Lincoln administration or by Mormon-controlled territorial probate courts. Moreover, as Mormon polygamist marriages were performed in secret, it was difficult to prove when a polygamist marriage had taken place. In the meantime, Congress was preoccupied with the American Civil War.

In 1874, after the war, Congress passed the Poland Act, which transferred jurisdiction over Morrill Act cases to federal prosecutors and courts, which were not controlled by Mormons. In addition, the Morrill Act was upheld in 1878 by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Reynolds v. United States. After Reynolds, Congress became even more aggressive against polygamy, and passed the Edmunds Act in 1882. The Edmunds Act prohibited not just bigamy, which remained a felony, but also bigamous cohabitation, which was prosecuted as a misdemeanor, and did not require proof an actual marriage ceremony had taken place. The Act also vacated the Utah territorial government, created an independent committee to oversee elections to prevent Mormon influence, and disenfranchised any former or present polygamist. Further, the law allowed the government to deny civil rights to polygamists without a trial.

In 1887, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which allowed prosecutors to force plural wives to testify against their husbands, abolished the right of women to vote, disincorporated the church, and confiscated the church's property.[28] By this time, many church leaders had gone into hiding to avoid prosecution, and half the Utah prison population was composed of polygamists.

Church leadership officially ended the practice in the United States in 1890, based on a decree of church president Wilford Woodruff called the 1890 Manifesto.

20th century

[edit]The church's modern era began soon after it renounced polygamy in 1890. Prior to the 1890 Manifesto, church leaders had been in hiding, many ecclesiastical matters had been neglected,[29] and the church organization itself had been disincorporated. With the reduction in federal pressure afforded by the Manifesto, however, the church began to re-establish its institutions.

World Wars

[edit]Throughout both World Wars, the LDS Church maintained a stance of neutrality, focusing on supporting its members spiritually and materially without endorsing any political sides. The church's leaders guided members through these challenging times by bolstering welfare programs and emphasizing faith. The wars notably influenced the LDS Church's international expansion and its role as a global religious organization committed to humanitarian efforts.

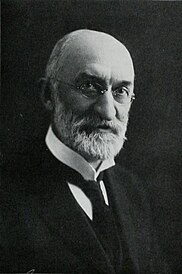

LDS Church in World War I

[edit]During World War I, the LDS Church was led by Joseph F. Smith, who navigated the church through the tumultuous period with a focus on neutrality and peace. Many members served in the military, and the church organized welfare and support efforts for those affected by the war.[30]

LDS Church in World War II

[edit]In World War II, the LDS Church, under the leadership of Heber J. Grant, continued its tradition of non-partisanship in global conflicts, while still supporting its members’ decisions to serve in their respective countries’ military forces. The church's extensive welfare system was pivotal during this time, providing support for both members and non-members affected by the war.[31]

Post-Manifesto polygamy and the Second Manifesto

[edit]The 1890 Manifesto did not, itself, eliminate the practice of new plural marriages, as they continued to occur clandestinely, mostly with church approval and authority.[32] In addition, most Mormon polygamists and every polygamous general authority continued to cohabit with their polygamous wives.[33] Mormon leaders, including Woodruff, maintained that the Manifesto was a temporary expediency designed to enable Utah to obtain statehood and that at some future date, the practice would soon resume.[34] Nevertheless, the 1890 Manifesto provided the church breathing room to obtain Utah's statehood, which it received in 1896 after a campaign to convince the American public that Mormon leaders had abandoned polygamy and intended to stay out of politics.[35]

Despite being admitted to the United States, Utah was initially unsuccessful in having its elected representatives and senators seated in the United States Congress. In 1898, Utah elected general authority B.H. Roberts to the United States House of Representatives as a Democrat. Roberts, however, was denied a seat there because he was practicing polygamy. In 1903, the Utah legislature selected Reed Smoot, also an LDS Church general authority but also a monogamist, as its first senator. From 1904 to 1907, the United States Senate conducted a series of Congressional hearings on whether Smoot should be seated. Eventually, the Senate granted Smoot a seat and allowed him to vote. However, the hearings raised controversy as to whether polygamy had actually been abandoned as claimed in the 1890 Manifesto, and whether the LDS Church continued to exercise influence on Utah politics. In response to these hearings, church president Joseph F. Smith issued a Second Manifesto denying that any post-Manifesto marriages had the church's sanction,[36] and announcing that those entering such marriages in the future would be excommunicated.

The Second Manifesto did not annul existing plural marriages within the church, and the church tolerated some degree of polygamy into at least the 1930s. However, eventually, the church adopted a policy of excommunicating its members found practicing polygamy and today seeks to actively distance itself from Mormon fundamentalist groups still practicing polygamy.[37] In modern times, members of the Mormon religion do not practice polygamy.

Involvement in national politics

[edit]Relationship to the women's suffrage movement

[edit]In 1870, the Utah Territory had become one of the first polities to grant women the right to vote—a right which the U.S. Congress revoked in 1887 as part of the Edmunds-Tucker Act.

As a result, a number of LDS women became active and vocal proponents of women's rights. Of particular note was the LDS journalist and suffragist Emmeline B. Wells, editor of the Woman's Exponent, a Utah feminist newspaper.[38] Wells, who was both a feminist and a polygamist, wrote vocally in favor of a woman's role in the political process and public discourse. National suffrage leaders, however, were somewhat perplexed by the seeming paradox between Utah's progressive stand on women's rights, and the church's stand on polygamy.

In 1890, after the church officially renounced polygamy, U.S. suffrage leaders began to embrace Utah's feminism more directly, and in 1891, Utah hosted the Rocky Mountain Suffrage Conference in Salt Lake City, attended by such national feminist leaders as Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw. The Utah Woman Suffrage Association, which had been formed in 1889 as a branch of the American Woman Suffrage Association (which in 1890 became the National American Woman Suffrage Association), was then successful in demanding that the constitution of the nascent state of Utah should enfranchise women. In 1896, Utah became the third state in the U.S. to grant women the right to vote.[39]

Debate over temperance and prohibition

[edit]The LDS Church was actively involved in support of the temperance movement in the 19th century, and later the prohibition movement under the presidency of Heber J. Grant.[40]

Relationship with socialism and communism

[edit]Mormonism has had a mixed relationship with socialism in its various forms. In the earliest days of Mormonism, Joseph Smith had established a form of Christian communalism, an idea made popular during the Second Great Awakening, combined with a move toward theocracy. Mormons referred to this form of theocratic communalism as the United Order, or the law of consecration. While short-lived during the life of Joseph Smith, the United Order was re-established for a time in several communities of Utah during the theocratic political leadership of Brigham Young. Some aspects of secular socialism also found a place in the political views of Joseph Smith. He ran for President of the United States on a platform that included a nationalized bank aimed at addressing the abuses of private banks.

As a secular political leader in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith introduced collective farms to support those lacking property, ensuring sustenance for the poor and their families. Upon reaching Utah, Brigham Young guided the church leadership in advocating for collective industry ownership. In 1876, a circular issued by them emphasized the importance of wealth distribution for liberty, warning against tyranny, oppression, and the vices arising from unequal wealth distribution. The circular, signed by the Quorum of the Twelve and the First Presidency, cautioned that continuous wealth concentration among the rich and deepening poverty among the poor could lead the nation toward disaster.[41]

In addition to religious socialism, many Mormons in Utah were interested in the secular socialist movement that began in America during the 1890s. During the 1890s to the 1920s, the Utah Social Democratic Party, which became part of the Socialist Party of America in 1901, elected about 100 socialists to state offices in Utah. An estimated 40% of Utah Socialists were Mormon. Many early socialists visited the Church's cooperative communities in Utah with great interest and were well received by the church leadership. Prominent early socialists such as Albert Brisbane, Victor Prosper Considerant, Plotino Rhodakanaty, Edward Bellamy, and Ruth & Reginald Wright Kauffman showed great interest in the successful cooperative communities of the church in Utah. For example, while doing research for what would become a best selling socialist novel, Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy toured the Church's cooperative communities in Utah and visited with Lorenzo Snow for a week.[42] Ruth & Reginald Wright Kauffman also wrote a book, though this one non-fiction, after visiting the Church in Utah. Their book was titled The Latter Day Saints: A Study of the Mormons in the Light of Economic Conditions, which discussed the Church from a Marxist perspective.[43] Socialist Plotino Rhodakanaty also became a prominent early church member in Mexico, after being baptized by a group of missionaries which included Moses Thatcher.[44] Thatcher kept in touch with Rhodakanaty for years following and was himself perhaps the most prominent member of the church to have openly identified himself as a socialist supporter.[citation needed]

Albert Brisbane and Victor Prosper Considerant also visited the church in Utah during its early years, prompting Considerant to note that "thanks to a certain dose of socialist solidarity, the Mormons have in a few years attained a state of unbelievable prosperity".[45] Attributing the peculiar socialist attitudes of the early Mormons to their success in the desert of the western United States was common even among those who were not themselves socialist. For instance, in his book History of Utah, 1540–1886, Hubert Howe Bancroft points out that the Mormons "while not communists, the elements of socialism enter strongly into all their relations, public and private, social, commercial, and industrial, as well as religious and political. This tends to render them exclusive, independent of the gentiles and their government, and even in some respects antagonistic to them. They have assisted each other until nine out of ten own their farms, while commerce and manufacturing are to large extent cooperative. The rights of property are respected; but while a Mormon may sell his farm to a gentile, it would not be deemed good fellowship for him to do so."[46]

While religious and secular socialism gained some acceptance among Mormons, the church was more circumspect about Marxist Communism because of its acceptance of violence as a means to achieve revolution. From the time of Joseph Smith, the church had taken a favorable view as to the American Revolution and the necessity at times to violently overthrow the government, however the church viewed the revolutionary nature of Leninist Communism as a threat to the United States Constitution, which the church saw as divinely inspired to ensure the agency of man.[a] In 1936, the First Presidency issued a statement which stated in part that “to support Communism is treasonable to our free institutions, and no patriotic American citizen may become either a Communist or supporter of Communism. ... [N]o loyal American citizen and no faithful church member can be a Communist.”[47] The strident atheism of Marxist thought may have also been considered incompatible with the church's fundamentally religious worldview.

In later years, such leaders as Ezra Taft Benson would take a stronger anti-Communist position publicly, his anti-Communism often being anti-leftist in general. However, the stridency of Benson's views was strongly disliked by others in the church's leadership, and even considered a point of embarrassment for the church.[48] Later, Benson would become church president and backed off of his political rhetoric. Toward the end of his presidency, the church even began to discipline church members who had taken Benson's earlier hardline right-wing speeches too much to heart, some of whom claimed that the church had excommunicated them for adhering too closely to Benson's right-wing ideology.[49]

Institutional reforms

[edit]Developments in Church financing

[edit]Soon after the 1890 Manifesto, the LDS Church was in a dire financial condition. It was recovering from the U.S. crackdown on polygamy, and had difficulty reclaiming property that had been confiscated during polygamy raids. Meanwhile, there was a national recession beginning in 1893. By the late 1890s, the church was about $2 million in debt, and near bankruptcy.[50] In response, Lorenzo Snow, then President of the Church, conducted a campaign to raise the payment of tithing, of which less than 20% of LDS had been paying during the 1890s.[51] After a visit to Saint George, Utah, which had a much higher-than-average percentage of full 10% tithe-payers,[52] Snow felt that he had received a revelation.[53] As a result of Snow's vigorous campaign, tithing payment increased dramatically from 18.4% in 1898 to an eventual peak of 59.3% in 1910.[54] From that time, payment of tithing has been a requirement for temple worship within the faith.[55]

I pray that every man, woman and child who has means shall pay one-tenth of their income as tithing.

During this timeframe, changes were made in stipends for bishops and general authorities. Bishops once received a 10% stipend from tithing funds, but are now purely volunteer. General authorities receive stipends, and formerly received loans from church funds.[citation needed]

Changes to meeting schedule

[edit]In earlier times, Latter-day Saint meetings occurred every Sunday morning and evening, with additional gatherings throughout the week. This structure was convenient for Utah Saints, as they typically resided within walking distance of a church building. However, outside of Utah, this meeting schedule presented logistical challenges. In 1980, the church implemented the "Consolidated Meeting Schedule," consolidating most church meetings into a three-hour block on Sundays.

In 2019, the meeting schedule was condensed into a two-hour block, with meetings during the second hour alternating between Sunday School and gendered (Relief Society / Priesthood) meetings.[57]

Changes to missionary service

[edit]In 1982, the First Presidency announced that the length of service of male full-time missionaries would be reduced to 18 months. In 1984, a little more than two years later, it was announced that the length of service would be returned to its original length of 24 months.[58]

Starting in 1990, paying for a mission became easier on those called to work in industrialized nations. Missionaries began paying into a church-wide general missionary fund instead of paying on their own. The amount paid into the fund does not vary by location; therefore, missionaries serving in low-cost-of-living-areas effectively subsidize missionaries serving in areas with higher costs.

Changes to church hierarchy and structure

[edit]During the 1960s, the church pursued a Priesthood Correlation Program, which streamlined and centralized the structure of the church. It had begun earlier in 1908, as the Correlation Program. The program increased church control over viewpoints taught in local church meetings.

During this time period, priesthood editorial oversight was established of formerly priesthood-auxiliary-specific YMMIA, YLMIA, Relief Society, Primary, and Sunday School magazines.

In 1911, the church adopted the Scouting program for its male members of appropriate age.

The Priesthood-Auxiliary movement (1928–1937) re-emphasized the church hierarchy around Priesthood, and re-emphasized other church organizations as "priesthood auxiliaries" with reduced autonomy.

LDS multiculturalism

[edit]As the church began to collide and meld with cultures outside of Utah and the United States, the church began to jettison some of the parochialisms and prejudices that had become part of Latter-day Saint culture but were not essential to Mormonism.[59] During and after the civil rights movement, the church faced a critical point in its history, where its previous attitudes toward other cultures and people of color, which had once been shared by much of the Anglo-American mainstream, carried racist and neocolonialist connotations. The mid-20th century saw the church critiqued over its positions on Black and Native American matters, especially the institution's bias towards European standards or norms at the expense and disregard of other racial or ethnic backgrounds' identity and humanity.[60]

The church and black people

[edit]The cause of some of the church's most damaging publicity had to do with the church's policy of discrimination against black people. Black people were always officially welcome in the church, and Joseph Smith established an early precedent for it by ordaining black males to the Priesthood. Smith was also anti-slavery, going so far as to run on an anti-slavery platform as a candidate for the presidency of the United States. At times, however, Smith had shown sympathy for the belief that black people were the cursed descendants of Cain, a belief which was commonly held in his day. In 1849, church doctrine taught that while black people could be baptized, black men could not be ordained to the Priesthood and black people could not enter LDS temples. Journal histories and public teachings of the time reflect that Young and others stated that God would some day reverse this policy of discrimination.

By the late 1960s, the church had expanded into Brazil, the Caribbean, and the nations of Africa, but it was also being criticized for its policy of racial discrimination. In the case of Africa and the Caribbean, the church had not yet begun large-scale missionary efforts in most areas. There were large groups of people who desired to join the church in Ghana and Nigeria and there were also many faithful church members who were of African descent in Brazil. On June 9, 1978, under the administration of Spencer W. Kimball, the church's leadership changed the long-standing policy.[61]

Today, there are many black members of the church, and there are also many predominantly black congregations. In the Salt Lake City area, black members have organized branches of an official church auxiliary[62] which is called the Genesis Groups.

The church and Native Americans

[edit]

During the post-World War II period, the church also began to focus on expansion into a number of Native American cultures, as well as Oceanic cultures, which many Mormons considered to be the same ethnicity. These peoples were called "Lamanites", because they were all believed to descend from the Lamanite group in the Book of Mormon. In 1947, the church began the Indian Placement Program, where Native American students (upon request by their parents) were voluntarily placed in Anglo Latter-day Saint foster homes during the school year, where they would attend public schools and become assimilated into Mormon culture.

In 1955, the church began ordaining black Melanesians to the Priesthood.

The church's policy toward Native Americans also came under fire during the 1970s. In particular the Indian Placement Program was criticized as neocolonial. In 1977, the U.S. government commissioned a study to investigate accusations that the church was using its influence to push children into joining the program. However, the commission rejected these accusations and found that the program was beneficial in many cases, and provided well-balanced American education for thousands, allowing the children to return to their cultures and customs. One issue was that the time away from family caused the assimilation of Native American students into American culture, rather than allowing the children to learn within, and preserve, their own culture. By the late 1980s, the program had been in decline, and in 1996, it was discontinued. In 2016, three lawsuits against the LDS Church were filed in the Navajo Nation District Court, alleging that participants in the program were sexually abused in their foster homes.[63] The church asked for the lawsuits to be dismissed on jurisdictional grounds, arguing that the alleged abuse took place outside the reservation.[63]

In 1981, the church published a new LDS edition of the Standard Works that changed a passage in The Book of Mormon that Lamanites (considered by many Latter-day Saints to be Native Americans) will "become white and delightsome" after accepting the gospel of Jesus Christ. Instead of continuing the original reference to skin color, the new edition replaced the word "white" with the word "pure".[citation needed]

Doctrinal reforms and influences

[edit]In 1927, the church implemented its "Good Neighbor policy", whereby it removed any suggestion in church literature, sermons, and ordinances that its members should seek vengeance on US citizens or governments, particularly for the assassinations of its founder Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum. The church also reformed the temple ordinance around this time to remove such references.[64]

Evolution

[edit]The issue of evolution has been a point of controversy for some members of the church. The first official statement on the issue of evolution was in 1909, which marked the centennial of Charles Darwin's birth and the 50th anniversary of his masterwork, On the Origin of Species. In that year, the First Presidency, led by Joseph F. Smith as president, issued a statement reinforcing the predominant religious view of creationism, and calling human evolution one of the "theories of men", but falling short of declaring evolution untrue or evil.

Soon after the 1909 statement, Joseph F. Smith professed in an editorial that "the church itself has no philosophy about the modus operandi employed by the Lord in His creation of the world."[65]

In 1925, as a result of publicity from the "Scopes Monkey Trial" concerning the right to teach evolution in Tennessee public schools, the First Presidency reiterated its 1909 stance, stating that "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, basing its belief on divine revelation, ancient and modern, declares man to be the direct and lineal offspring of Deity."[citation needed]

In the early 1930s there was an intense debate between liberal theologian and general authority B. H. Roberts and some members of the Council of the Twelve Apostles over attempts by B. H. Roberts to reconcile the fossil record with the scriptures by introducing a doctrine of pre-Adamite creation, and backing up this speculative doctrine using geology, biology, anthropology, and archeology.[66] More conservative members of the Twelve Apostles, including Joseph Fielding Smith, rejected his speculation because it contradicted the idea that there was no death until after the fall of Adam. James E. Talmage published a book through the LDS Church that explicitly stated that organisms lived and died on this earth before the earth was fit for human habitation.[67]

The debate over pre-Adamites has been interpreted by LDS proponents of evolution as a debate about organic evolution. This view, based on the belief that a dichotomy of thought on the subject of evolution existed between B. H. Roberts and Joseph Fielding Smith, has become common among pro-evolution members of the church. As a result, the ensuing 1931 statement has been interpreted by some as official permission for members to believe in organic evolution.[68]

Later, Joseph Fielding Smith published his book Man: His Origin and Destiny, which denounced evolution without qualification. Similar statements of denunciation were made by Bruce R. McConkie, who in 1980 denounced evolution as one of "the seven deadly heresies."[69] Evolution was also denounced by the conservative apostle Ezra Taft Benson, who in 1975 called on church members to use the Book of Mormon to combat evolution and several times denounced evolution as a "falsehood" on a par with socialism, rationalism, and humanism.[70]

A dichotomy of opinion exists among church members today. Largely influenced by Smith, McConkie, and Benson, evolution is rejected by a large number of conservative church members.[71] A minority[citation needed] accept evolution, supported in part by the debate between B. H. Roberts and Joseph Fielding Smith, in part by a large amount of scientific evidence, and in part by Joseph F. Smith's words that "the church itself has no philosophy about the modus operandi employed by the Lord in His creation of the world." Meanwhile, Brigham Young University, the largest private university owned and operated by the church, not only teaches evolution to its biology majors, but has also done significant research in evolution.[72] BYU-I, another church-run school, also teaches it.[73][74][75][76]

A 2018 study in PLOS One researched the attitudes toward evolution of Latter-day Saint undergraduates. The study revealed that there has been a recent shift of attitude towards evolution among LDS undergraduates, from antagonistic to more accepting. The researchers cited examples of more acceptance of fossil and geological records, as well as an acceptance of the old age of the earth. The researchers attributed this attitude change to several factors including primary-school exposure to evolution and a reduction in the number of anti-evolution statements from the First Presidency.[77]

Reacting to pluralism

[edit]The church was opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment.[78]

In 1995, the church issued The Family: A Proclamation to the World.

The church opposes same-sex marriage, but does not object to rights regarding hospitalization and medical care, fair housing and employment rights, or probate rights, so long as these do not infringe on the integrity of the family or the constitutional rights of churches and their adherents to administer and practice their religion free from government interference.[79] The church supported a gay rights bill in Salt Lake City which bans discrimination against gay men and lesbians in housing and employment, calling them "common-sense rights."[80][81]

Some church members have formed a number of unofficial support organizations, including Evergreen International, Affirmation: Gay & Lesbian Mormons, North Star,[82] Disciples2,[83] Wildflowers,[84] Family Fellowship, GLYA (Gay LDS Young Adults),[85] LDS Reconciliation,[86] Gamofites and the Guardrail foundation.[87] Church leaders have met with people from Evergreen International, Inc. and several gay rights leaders.[88]

Challenges to fundamental church doctrine

[edit]In 1967, a set of papyrus manuscripts were discovered in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that appear to be the manuscripts from which Joseph Smith said to have translated the Book of Abraham in 1835. These manuscripts were presumed lost in the Chicago fire of 1871. Analyzed by Egyptologists, the manuscripts were identified as The Book of the Dead, an ancient Egyptian funerary text. Moreover, the scholars' translations of the scrolls disagreed with Smith's purported translation.[89][90] This discovery forced many Mormon apologists to moderate the earlier prevailing view that Smith's translations were literal one-to-one translations.

In the early 1980s, the apparent discovery of an early Mormon manuscript, which came to be known as the "Salamander Letter", received much publicity. This letter, reportedly discovered by a scholar named Mark Hofmann, alleged that the Book of Mormon was given to Joseph Smith by a being that changed itself into a salamander, not by an angel as the official church history recounted. The document was purchased by private collector Steven Christensen, but was still significantly publicized and even printed in the church's official magazine, the Ensign. The document, however, was revealed as a forgery in 1985, and Hofmann was arrested for two murders related to his forgeries.[91]

Mormon dissidents and scholars

[edit]In 1989, George P. Lee, a Navajo member of the First Quorum of the Seventy who had participated in the Indian Placement Program in his youth, was excommunicated.[92] The church action occurred not long after he had submitted to the Church a 23-page letter critical of the program and the effect it had on Native American culture. In October 1994, Lee confessed to, and was convicted of, sexually molesting a 13-year-old girl in 1989. It is not known if church leaders had knowledge of this crime during the excommunication process.

In the late 1980s, the administration of Ezra Taft Benson formed what it called the Strengthening Church Members Committee, to keep files on potential church dissidents and collect their published material for possible later use in church disciplinary proceedings. The existence of this committee was first publicized by an anti-Mormon ministry in 1991, when it was referred to in a memo dated July 19, 1990 leaked from the office of the church's Presiding Bishopric.

At the 1992 Sunstone Symposium, dissident Mormon scholar Lavina Fielding Anderson accused the Committee of being "an internal espionage system," which prompted Brigham Young University professor and moderate Mormon scholar Eugene England to "accuse that committee of undermining the Church," a charge for which he later publicly apologized.[93] The publicity concerning the statements of Anderson and England, however, prompted the church to officially acknowledge the existence of the committee.[94] The Church explained that the Committee "provides local church leadership with information designed to help them counsel with members who, however well-meaning, may hinder the progress of the church through public criticism."[95]

Official concern about the work of dissident scholars within the church led to the excommunication or disfellowshipping of six such scholars, dubbed the September Six, in September 1993.[96]

Latter-day Saint public relations

[edit]

In the 1960s, the church formed the Church Information Service with the goal of being ready to respond to media inquiries and generate positive media coverage. The organization kept a photo file to provide photos to the media for such events as Temple dedications. It also worked to get stories covering Family Home Evening, the church welfare plan and the church's youth activities in various publications.[97]

As part of the church's efforts to re-position its image as that of a mainstream religion, the church began to moderate its earlier anti–Roman Catholic rhetoric. In Bruce R. McConkie's 1958 edition of Mormon Doctrine, he had stated his unofficial opinion that the Catholic Church was part of "the church of the devil" and "the great and abominable church" because it was among organizations that misled people away from following God's laws. In his 1966 edition of the same book, the specific reference to the Catholic Church was removed.[b]

According to Riess and Tickle, early Mormons rarely quoted from the Book of Mormon in their speeches and writings. It was not until the 1980s that it was cited regularly in speeches given by LDS Church leaders at the biannual general conferences. In 1982, the LDS Church subtitled the Book of Mormon "Another Testament of Jesus Christ." Apostle Boyd K. Packer stated that the scripture now took its place "beside the Old Testament and the New Testament.[98] Riess and Tickle assert that the introduction of this subtitle was intended to emphasize the Christ-centered nature of the Book of Mormon. They assert that the LDS "rediscovery of the Book of Mormon in the late twentieth century is strongly connected to their renewed emphasis on the person and nature of Jesus Christ."[99]

In 1995, the church announced a new logo design that emphasized the words "JESUS CHRIST" in large capital letters, and de-emphasized the words "The Church of" and "of Latter-day Saints".[100]

21st century

[edit]On January 1, 2000, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles released a proclamation entitled "The Living Christ: The Testimony of the Apostles". This document commemorated the birth of Jesus and set forth the church's official view regarding Christ.

The church has participated in several interfaith cooperation initiatives. The church has opened its broadcasting facilities (Bonneville International) to other Christian groups and has participated in the VISN Religious Interfaith Cable Television Network. The church has also participated in numerous joint humanitarian efforts with other churches. Lastly, the church has agreed not to baptize Holocaust victims by proxy.

Beginning in 2001, the church also sponsors or sponsored a low-interest educational loan program known as the Perpetual Education Fund, which provides or provided educational opportunities to students from developing nations.[101][102]

In 2004, the church endorsed an amendment to the United States Constitution banning homosexual marriage. The church also announced its opposition to political measures that "confer legal status on any other sexual relationship" than a "man and a woman lawfully wedded as husband and wife."[103]

On November 5, 2015, an update letter to LDS Church leaders for the Church Handbook was leaked. The policy banned a "child of a parent living in a same-gender relationship" from baby blessings, baptism, confirmation, priesthood ordination, and missionary service until the child was not living with their homosexual parent(s), was "of legal age", and "disavow[ed] the practice of same-gender cohabitation and marriage", in addition to receiving approval from the Office of the First Presidency. The policy update also added that entering a same-sex marriage as a type of "apostasy", mandating a disciplinary council.[104][105] The next day, in a video interview, apostle D. Todd Christofferson clarified that the policy was "about love" and "protect[ing] children" from "difficulties, challenges, conflicts" where "parents feel one way and the expectations of the Church are very different".[106] On November 13, the First Presidency released a letter clarifying that the policy applied "only to those children whose primary residence is with a couple living in a same-gender marriage or similar relationship" and that for children residing with parents in a same-sex relationship who had already received ordinances the policy would not require that "privileges be curtailed or that further ordinances be withheld".[107][108] The next day around 1,500 members gathered across from the Church Office Building to submit their resignation letters in response to the policy change with thousands more resigning online in the weeks after[109][110][111][112] Two months later, in a satellite broadcast, apostle Russell M. Nelson stated that the policy change was "revealed to President Monson" in a "sacred moment" when "the Lord inspired [him] ... to declare ... the will of the Lord".[113] In April 2019, the church—then led by Nelson—reversed these policies, citing efforts to be more accepting to people of all kinds of backgrounds.[114][115]

For over 100 years, the church was a major sponsor of Scouting programs for boys, particularly in the United States. The LDS Church was the largest chartered organization in the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), having joined the BSA as its first charter organization in 1913.[116] In 2020, the church ended its relationship with the BSA and began an alternate, religion-centered youth program, which replaced all other youth programs.[117] Prior to leaving the Scouting program, LDS Scouts made up nearly 20 percent of all enrolled Boy Scouts,[118] more than any other church.[119]

Legal entities and merger

[edit]In 1887, the LDS Church was legally dissolved in the United States by the Edmunds–Tucker Act because of the church's practice of polygamy.[120] For more than the next hundred years, the church as a whole operated as an unincorporated entity.[121] During that time, tax-exempt corporations of the LDS Church included the Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which managed non-ecclesiastical real estate and other holdings; and the Corporation of the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which governed temples, other sacred buildings, and the church's employees. By 2021, the two had been merged into one corporate entity, legally named "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints."[122]

Ensign Peak Advisors

[edit]In December 2019, a whistleblower alleged the church held over $100 billion in investment funds through its investment management company, Ensign Peak Advisors (EP); that it failed to use the funds for charitable purposes and instead used them in for-profit ventures; and that it misled contributors and the public about the usage and extent of those funds.[123][124] In response, the church's First Presidency stated that "the Church complies with all applicable law governing our donations, investments, taxes, and reserves," and that "a portion" of funds received by the church are "methodically safeguarded through wise financial management and the building of a prudent reserve for the future".[125] The church has not directly addressed the fund's size to the public, but third parties have treated the disclosures as legitimate.[126][127]

In February 2023, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued a $5 million penalty to the church and its investment company, EP. The SEC alleged that the church concealed its investments and their management in multiple shell companies from 1997 to 2019; the SEC believes these shell companies were approved by senior church leadership to avoid public transparency.[128] The church released a statement that in 2000 EP "received and relied upon legal counsel regarding how to comply with its reporting obligations while attempting to maintain the privacy of the portfolio." After initial SEC concern in June 2019, the church stated that EP "adjusted its approach and began filing a single aggregated report."[129]

See also

[edit]- Church History Museum

- Christian communism

- Criticism of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Cunning Folk Traditions and the Latter Day Saint Movement

- History of the Church (Joseph Smith)

- History of the Latter Day Saint movement

- Latter Day Saint Historians

- List of denominations in the Latter Day Saint movement

- List of historic sites of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Mormon studies

- Mormonism and history

- Mormonism and Pacific Islanders

- Restoration movement

- Restorationism (Christian primitivism)

- Saints: The Story of the Church of Jesus Christ in the Latter Days

- The Joseph Smith Papers

- Temperance organizations

- Utah-Idaho Sugar Company

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mormonism believes God revealed to Joseph Smith in Chapter 101 of the Doctrine and Covenants that "the laws and constitution of the people ... I have suffered to be established, and should be maintained for the rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles"

- ^ See generally: Armand L. Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994); Gordon Sheperd & Gary Sheperd, "Mormonism in Secular Society: Changing Patterns in Official Ecclesiastical Rhetoric," Review of Religious Research 26 (Sept. 1984): 28-42.

References

[edit]- ^ Embry, Jesse L. (2018). "Mormons". Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021.

- ^ Bushman, Richard L. (1988). Joseph Smith and the beginnings of Mormonism (Illini Books ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252060120.

- ^ Hansen, Klaus J. (1981). Mormonism and the American experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226315522.

- ^ Allen, James B. (1994), "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on December 7, 2023, retrieved April 9, 2024

- ^ "Revelation". josephsmithpapers.org. 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org. 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ^ "Scriptures". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 2007-12-25.: "On September 22, 1827, an angel named Moroni—the last Book of Mormon prophet—delivered these records to the Prophet Joseph Smith."

- ^ The Church of Christ was organized in the log cabin of Joseph Smith, Sr. in the Manchester area, near Rochester, followed by a meeting the next Sunday in nearby Fayette at the house of Peter Whitmer, Sr. Nevertheless, one of Smith's histories and an 1887 reminiscence by David Whitmer say the church was organized at the Whitmer house in Fayette. (Whitmer, however, had already told a reporter in 1875 that the church was organized in Manchester. Whitmer, John C. (August 7, 1875), "The Golden Tables", Chicago Times.) The LDS Church refers to Fayette as the place of organization in all its official publications.

- ^ Smith, Joseph (1835). Doctrine and Covenants 57. pp. 57:1–3.

- ^ D&C 32

- ^ The Deseret Morning News 2008 Church Almanac pg.655

- ^ Prentiss, Craig R. (2003). ""Loathsome unto Thy People": The Latter-day Saints and Racial Categorization". Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction. NYU Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8147-6882-2.

Mormons were accused by their persecutors in Missouri of being abolitionists and trying to promote slave rebellions

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1994), The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, pp. 124, 643, ISBN 1-56085-056-6

- ^ Nauvoo Expositor.

- ^ History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints volume VI (1912), pp. 430-432. The council met on June 8 and June 10 to discuss the matter.

- ^ History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints volume VI (1912), p. 432: "The Council passed an ordinance declaring the Nauvoo Expositor a nuisance, and also issued an order to me to abate the said nuisance. I immediately ordered the Marshall to destroy it without delay." – Joseph Smith

- ^ Encyclopedia of Latter-Day Saint History pg. 824.

- ^ Andrus, Hyrum Leslie (1973), Doctrines of the Kingdom, Salt lake City, UT: Bookcraft, p. 12, republished as Andrus, Hyrum L. (1999), Doctrines of the Kingdom: Volume III from the Series Foundations of the Millennial Kingdom of Christ, Salt lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 1-57345-462-1

- ^ Harper 1996; Lynne Watkins Jorgensen, "The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith Passes to Brother Brigham: One Hundred Twenty-one Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness" in John W. Welch (ed.), 2005. Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820-1844, Provo, Utah: BYU Press, pp. 374-480; Eugene English, "George Laub Nauvoo Diary," BYU Studies, 18 [Winter 1978]: 167; William Burton Diary, May 1845. LDS Church Archives; Benjamin F. Johnson, My Life's Review [Independence, 1928], p. 103-104; Life Story of Mosiah Hancock, p. 23, BYU Library; Wilford Woodruff, Deseret News, 15 March 1892; George Q. Cannon, Juvenile Instructor, 22 [29 October 1870]: 174-175.

- ^ Alexander, Thomas G. (February 2000). Woodruff, Wilford (1807-1898), fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and church prophet. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0801701.

- ^ Holder, R. Ward (2018-12-12). "On the Worth of Church History". Church History and Religious Culture. 98 (3–4): 315–318. doi:10.1163/18712428-09803023. ISSN 1871-241X. S2CID 195466093.

- ^ (Mangrum 1983, pp. 80–81)

- ^ Peterson, Paul H. "The Mormon Reformation of 1856-1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality." 15 Journal of Mormon History 59-87 (1989).

- ^ "Blood Atonement and the Early Mormon Church". law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; King, Gilbert. "The Aftermath of Mountain Meadows". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ Johnson, Jeffery Ogden (1987). "Determining and Defining 'Wife': The Brigham Young Households" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 20 (3): 57–70. doi:10.2307/45225560. JSTOR 45225560. S2CID 254339939.

- ^ Jessee, Dean C. (2001). ""A Man of God and a Good Kind Father": Brigham Young at Home". Brigham Young University Studies. 40 (2): 23–53. ISSN 0007-0106. JSTOR 43042842.

- ^ a b Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. United States, 136 U.S. 1 (1890)

- ^ Lyman, Edward Leo (1998), "Mormon Leaders in Politics: The Transition to Statehood in 1896", Journal of Mormon History, 24 (2): 30–54, at 31, archived from the original on 2011-06-13

- ^ "World War I". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

- ^ "Chapter Forty: The Saints during World War II". 2018-04-05. Archived from the original on 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1985), "LDS Church Authority and New Plural Marriages, 1890–1904", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 18 (1): 9–105, at 56, doi:10.2307/45225323, JSTOR 45225323, S2CID 259871046 (stating that 90% of polygamous marriages between 1890 and 1904 were contracted with church authority).

- ^ Quinn at 51.

- ^ Lyman, 1998, p. 39-40.

- ^ Lyman, 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Later scholars, however, have determined that 90% of polygamous marriages between 1890 and 1904 were, in fact, conducted under church authority. See Quinn at 56.

- ^ In 1998 President Gordon B. Hinckley stated,

"If any of our members are found to be practicing plural marriage, they are excommunicated, the most serious penalty the Church can impose. Not only are those so involved in direct violation of the civil law, they are in violation of the law of this Church."

Gordon B. Hinckley, "What Are People Asking About Us?", Ensign, November 1998, p. 70. - ^ Brown, Barbara. "Emmeline B. Wells, A Thinking Woman". Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Women’s Suffrage in Utah. National Park Service. N.d. Accessed December 25, 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Brent G. (1983), "'Standing between Two Fires': Mormons and Prohibition, 1908–1917", Journal of Mormon History, 10: 35–52, archived from the original on 2011-06-13

- ^ Clark, James R. (1833–1955), Messages of the First Presidency Volume 2

- ^ Arrington, Leonard J. (1986), Brigham Young: American Moses, p. 378

- ^ Kauffman, Ruth and Reginald. The Latter Day Saints: A Study of the Mormons in the Light of Economic Conditions. London: Williams & Norgate, 1912.

- ^ Murphy, Thomas W. (2000). "Other Mormon Histories: Lamanite Subjectivity in Mexico". Journal of Mormon History. 26 (2): 179–214. ISSN 0094-7342. JSTOR 23288220.

- ^ Beacher, Jonathan (2001), Victor Considerant and the Rise and Fall of French Romantic Socialism, p. 301

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe, History of Utah, 1540-1886, p. 306

- ^ First Presidency, "Warning to Church Members," July 3, 1936, Improvement Era 39, no. 8 (August 1936): 488.

- ^ Prince, Gregory A. (2005), David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, pp. 279–323

- ^ Chris Jorgensen and Peggy Fletcher Stack (1992), "It's Judgment Day for Far Right: LDS Church Purges Survivalists", The Salt Lake Tribune, 29 November 1992 Sunday Edition, Page A1

- ^ Bell, E. Jay (1994), "The Windows of Heaven Revisited: The 1899 Tithing Reformation", Journal of Mormon History, 19 (2): 45–83, at 45–46, archived from the original on 2011-06-13

- ^ Bell, 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Bell, 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Bell, 1994, p. 65.

- ^ Bell, 1994, p. 82.

- ^ Reexamining Lorenzo Snow’s 1899 Tithing Revelation, by Dennis Horne. Mormon Historical Studies. Pg. 148 “[Snow] informed the people that members who did not comply with the commandment to pay a full tithing would not be called to ecclesiastical positions of responsibility, nor be considered worthy to enter the temple.”

- ^ 1899 Conference Report

- ^ Members praise, criticize LDS Church move to two-hour Sunday services. KUTV. January 7, 2019. Accessed December 15, 2023.

- ^ Dialogue journal Archived 2005-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 21 Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 97 (Fall 1988)

- ^ Mueller, Max Perry (2014). "Black, White, and Red: Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830-1880" (PDF). Harvard Library. Retrieved November 23, 2023.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants, OD-2

- ^ "Genesis Group". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- ^ a b Fowler, Lilly (23 October 2016). "Why Several Native Americans Are Suing the Mormon Church". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ George D. Pyper (1939). Stories of the Latter-day Saint Hymns, their Authors and Composers p. 100.

- ^ Juvenile Instructor, 46 (4), 208-209 (April 1911).

- ^ The Truth, The Way, The Life, pp. 238–240; 289–296.

- ^ Talmage, James E. (November 21, 1931) "The Earth and Man"

- ^ "A Major Defect in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism article about Evolution".

- ^ BYU Fireside, June 1, 1980

- ^ Ezra Taft Benson, Conference Report, April 5, 1975

- ^ [1] Archived June 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] Archived September 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Firestone, Lynn. "A Delicate Balance: Teaching Biological Evolution at BYU-Idaho" (PDF). Perspectives. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Sherlock, R. Richard (1978). "A Turbulent Spectrum: Mormon Reactions to the Darwinist Legacy". Journal of Mormon History. 5: 33–60. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06.

- ^ Trent D. Stephens, D. Jeffrey Meldrum, & Forrest B. Peterson, Evolution and Mormonism: A Quest for Understanding Archived 2001-04-13 at the Wayback Machine (Signature Books, 2001).

- ^ Hurst, Alan. "Unifying Truth: Analysis of the Conflict between Reason and Revelation". Selections from the Religious Education Student Symposium 2005. BYU Religious Studies Center. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, William S.; Phillips, Andrea J.; Bybee, Seth M.; Gill, Richard A.; Peck, Steven L.; Jensen, Jamie L. (November 7, 2018). "A longitudinal study of attitudes toward evolution among undergraduates who are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0205798. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305798B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205798. PMC 6221276. PMID 30403685.

- ^ *#Quinn, D. Michael, "The LDS Church's Campaign Against the Equal Rights Amendment", Journal of Mormon History, 20 (2): 85–155, archived from the original on 2011-06-13

- ^ "The Divine Institution of Marriage". LDS Church. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (11 November 2009), "Mormon Support of Gay Rights Statute Draws Praise", The New York Times

- ^ "Statement Given to Salt Lake City Council on Nondiscrimination Ordinances", Newsroom, LDS Church, 1 January 2009

- ^ "North Star". Northstarlds.org. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ "Disciples2 Homepage". Disciples2.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ Home Page

- ^ "GLYA". Glya.homestead.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2005. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ "Gay Mormon LDS Reconciliation". LDS Reconciliation. 2004-01-01. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ "The Guardrail Foundation". Theguardrail.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ^ Canham, Matt; Jensen, Derek P.; Winters, Rosemary (10 November 2009). "Salt Lake City adopts pro-gay statutes -- with LDS Church support". Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Wilson, John A. (Summer 1968). "A Summary Report". The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: Translations and Interpretations. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 3 (2): 67–88. doi:10.2307/45227259. JSTOR 45227259. S2CID 254343491.

- ^ Ritner, Robert K. "Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham: A Response" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Lindsey, Robert (1988). A Gathering of Saints: A True Story of Money, Murder, and Deceit. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-65112-9 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Disciplinary action taken Sept. 1 against general authority". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. LDS Church News. September 9, 1989. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Letter to the Editor, Sunstone, March 1993.

- ^ "Mormon Church keeps files on its dissenters," St. Petersburg Times, Aug. 15, 1992, at 6e.

- ^ "Secret Files," New York Times, Aug. 22, 1992.

- ^ "Six intellectuals disciplined for apostasy." Sunstone, November 1993, 65-73.

- ^ Richard O. Cowan. The Church in the 20th Century (Bookcraft: Salt Lake City, 1985) p. 289

- ^ "Since 1982, subtitle has defined book as 'another testament of Jesus Christ'", 2 January 1988, Church News

- ^ Riess, Jana; Tickle, Phyllis (2005), The book of Mormon: selections annotated & explained, SkyLight Paths Publishing, pp. xiii–xiv, ISBN 978-1-59473-076-4

- ^ "New logo re-emphasizes official name of Church". Church News. 1995-12-23. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- ^ "LDS Perpetual Education Fund". Philanthropy Roundtable. 2001. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Newton, Michael R. (2011). "The Perpetual Education Fund: A Model for Educational Microfinance?". SSRN Electronic Journal. Social Science Research Network: 1. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1822669. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 153356848.

- ^ "First Presidency Statement on Same-Gender Marriage", October 19, 2004).

- ^ Shill, Aaron (5 Nov 2015). "LDS Church reaffirms doctrine of marriage, updates policies on families in same-sex marriages". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Bailey, Sarah Pulliam (11 Nov 2016). "Mormon Church to exclude children of same-sex couples from getting blessed and baptized until they are 18". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Church Provides Context on Handbook Changes Affecting Same-Sex Marriages". Mormon Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Otterson, Michael (13 November 2015). "Understanding the Handbook". Mormon Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "First Presidency Clarifies Church Handbook Changes". churchofjesuschrist.org. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Moyer, Justin (16 November 2015). "1,500 Mormons quit church over new anti-gay-marriage policy, organizer says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Healy, Jack (15 November 2016). "Mormon Resignations Put Support for Gays Over Fealty to Faith". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Vazquez, Aldo (14 November 2015). "Thousands file resignation letters from the LDS Church". ABC 4 Utah KTVX. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Levin, Sam (15 August 2016). "'I'm not a Mormon': fresh 'mass resignation' over anti-LGBT beliefs". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Nelson, Russell M. "Becoming True Millennials". churchofjesuschrist.org. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Stack, Peggy Fletcher. "LDS Church dumps its controversial LGBTQ policy, cites continuing 'revelation' from God". sltrib.com. Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "First Presidency Shares Messages From General Conference Leadership Session". Mormon Newsroom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. April 4, 2019. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Scott (May 8, 2018). "Timeline of the Church and Boy Scouts of America". Church News. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Hopkinson, Savannah (May 9, 2018). "Church to End Relationship with Scouting; Announces New Activity Program for Children and Youth". Church News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Mormon Church breaks all ties with Boy Scouts, ending 100-year relationship". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Boy Scouts of America Membership Report – 2007 (PDF), P.R.A.Y., January 7, 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008, retrieved May 22, 2008

- ^ Montoya, Maria; Belmonte, Laura A.; Guarneri, Carl J.; Hackel, Steven; Hartigan-O'Connor, Ellen (2016). Global Americans: A History of the United States. Cengage Learning. p. 442. ISBN 9781337515672. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Munoz, Vincent Phillip (2015). Religious Liberty and the American Supreme Court: The Essential Cases and Documents. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 312. ISBN 9781442250321. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "LDS Corp. — The church long's journey to stay on the right side of the law and its principles". Salt Lake Tribune. June 1, 2021. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ Swaine, Jon; MacMillan, Douglas; Boorstein, Michelle (December 16, 2019). "Mormon Church has misled members on $100 billion tax-exempt investment fund, whistleblower alleges". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Stilson, Ashley (17 December 2019). "LDS Church leaders defend use of tithes, donations after whistleblower alleges misuse". Daily Herald. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Swaine, Jon; MacMillan, Douglas; Boorstein, Michelle (2020-01-06). "Mormon Church has misled members on $100 billion tax-exempt investment fund, whistleblower alleges". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ "The Mormon Church Amassed $100 Billion. It Was the Best-Kept Secret in the Investment World". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "LDS Church kept the lid on its $100B fund for fear tithing receipts would fall, account boss tells The Wall Street Journal". Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ McKernan, Elizabeth (February 24, 2023). "How the SEC believes the LDS Church hid billions of dollars from the public since 1997". KUTV.

- ^ Wile, Rob (23 February 2023). "Feds fine Mormon church for illicitly hiding $32 billion investment fund behind shell companies". NBC News.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, James and Leonard, Glen M. (1976, 1992) The Story of the Latter-day Saints; Deseret Book; ISBN 0-87579-565-X

- Arrington, Leonard J. (1979). The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints; University of Illinois Press; ISBN 0-252-06236-1 (1979; Paperback, 1992)

- Arrington, Leonard J. (1958). Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900; University of Illinois Press; ISBN 0-252-02972-0 (1958; Hardcover, October 2004).

- Givens, Terryl L. The Latter-day Saint Experience in America (The American Religious Experience) Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-32750-5.

- Harper, Reid L. (1996). "The Mantle of Joseph: Creation of a Mormon Miracle". Journal of Mormon History. 22 (2): 35–71. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13.

- May, Dean L. Utah: A People's History. Bonneville Books, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1987. ISBN 0-87480-284-9.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1985), "LDS Church Authority and New Plural Marriages, 1890-1904 Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 18.1 (Spring 1985): 9–105.

- Roberts, B. H. (1930). A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century I 6 volumes; Brigham Young University Press; ISBN 0-8425-0482-6 (1930; Hardcover 1965) (out of print)

- Smith, Joseph (1902–32). History of the Church, 7 volumes; Deseret Book Company; ISBN 0-87579-486-6 (1902–1932; Paperback, 1991)

- Mangrum, R. Collin (1983), "Furthering the Cause of Zion: An Overview of the Mormon Ecclesiastical Court System in Early Utah", Journal of Mormon History, 10: 79–90, archived from the original on 2011-06-13.

External links

[edit]- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Saints: The Story of The Church of Jesus Christ in the Latter Days (LDS Church, 2018).

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Chronology of Church History (LDS Church, 2000).