History of women in the United Kingdom

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 55 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 55 min

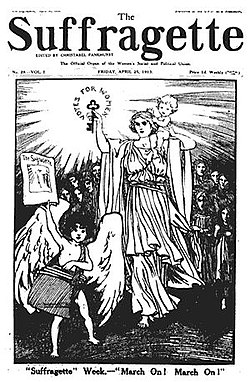

Cover of WSPU's The Suffragette, 25 April 1913 | |

| Gender Inequality Index[1] | |

|---|---|

| Value | 0.098 (2021) |

| Rank | 27th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.775 (2021) |

| Rank | 23rd |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

History of women in the United Kingdom covers the social, cultural, legal and political roles of women in Britain over the last 600 years and more. Women's roles have transformed from being tightly confined to domestic spheres to becoming active participants in all facets of society, driven by social movements, economic changes, and legislative reforms.

In terms of public culture, five centuries ago women played limited roles in religious practices and cultural patronage, particularly among the nobility. The Victorian Era uplifted the "ideal woman" as a moral guardian of the home. Literature and art often reinforced these stereotypes. The sexual revolution of the 1960s challenged traditional norms, with women gaining more freedom in fashion, relationships, and self-expression.

Legal roles expanded dramatically :At first women had limited legal rights but could own property as widows or freeholders. The law subordinated them to male relatives or feudal lords. By the 1880s new laws allowed married women to own property independently for the first time. More recently, Landmark legislation like the Equal Pay Act (1970) and Sex Discrimination Act (1975) advanced women's legal equal rights in employment and education.

In terms of politics, at first women were excluded from formal politics, apart from a reigning queen. Women gained the right to vote in 1918 to 1928. They had a very small role in Parliament until Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in 1979. Since then their political participation has increased significantly in all sectors.

Medieval

[edit]

Medieval England was a patriarchal society and the lives of women were heavily influenced by contemporary beliefs about gender and authority.[3][4] However, the position of women varied according to factors including their social class; whether they were unmarried, married, widowed or remarried; and in which part of the country they lived.[5] Henrietta Leyser argues that women had much informal power in their homes and communities, although they were of officially subordinate to men. She identifies a deterioration the status of women in the Middle Ages, although they retained strong roles in culture and spirituality.[6]

Significant gender inequities persisted throughout the period, as women typically had more limited life-choices, access to employment and trade, and legal rights than men. After the Norman invasion, the position of women in society changed. The rights and roles of women became more sharply defined, in part as a result of the development of the feudal system and the expansion of the English legal system; some women benefited from this, while others lost out. The rights of widows were formally laid down in law by the end of the twelfth century, clarifying the right of free women to own property, but this did not necessarily prevent women from being forcibly remarried against their wishes. The growth of governmental institutions under a succession of bishops reduced the role of queens and their households in formal government. Married or widowed noblewomen remained significant cultural and religious patrons and played an important part in political and military events, even if chroniclers were uncertain if this was appropriate behaviour. As in earlier centuries, most women worked in agriculture, but here roles became more clearly gendered, with ploughing and managing the fields defined as men's work, for example, and dairy production becoming dominated by women.[7][8]

In medieval times, women had responsibility for brewing and selling the ale that men all drank. By 1600, men had taken over that role. The reasons include commercial growth, gild formation, changing technologies, new regulations, and widespread prejudices that associated female brewsters with drunkenness and disorder. The taverns still use women to serve it, a low-status, low-skilled, and poorly remunerated tasks.[9]

Early modern period

[edit]Tudor era

[edit]

While the Tudor era presents an abundance of material on the women of the nobility—especially royal wives and queens—historians have recovered scant documentation about the average lives of women. There has, however, been extensive statistical analysis of demographic and population data which includes women, especially in their childbearing roles.[10][11]

The role of women in society was, for the historical era, relatively unconstrained; Spanish and Italian visitors to England commented regularly, and sometimes caustically, on the freedom that women enjoyed in England, in contrast to their home cultures. England had more well-educated upper-class women than was common anywhere in Europe.[12][13]

Queen Elizabeth I's marital status was a major political and diplomatic topic. It also entered into the popular culture. Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin or a goddess or both, not as a normal woman.[14] Elizabeth made a virtue of her virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin".[15] Public tributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion of opposition to the queen's marriage negotiations with the Duc d'Alençon.[16]

In contrast to her father's emphasis on masculinity and physical prowess, Elizabeth emphasised the maternalism theme, saying often that she was married to her kingdom and subjects. She explained "I keep the good will of all my husbands — my good people — for if they did not rest assured of some special love towards them, they would not readily yield me such good obedience,"[17] and promised in 1563 they would never have a more natural mother than she.[18] Coch (1996) argues that her figurative motherhood played a central role in her complex self-representation, shaping and legitimating the personal rule of a divinely appointed female prince.[19]

Medical care

[edit]Although medical men did not approve, women healers played a significant role in the medical care of Londoners from cradle to grave during the Elizabethan era. They were hired by parishes and hospitals, as well as by private families. They played central roles in the delivery of nursing care as well as medical, pharmaceutical, and surgical services throughout the city as part of organised systems of health care.[20] Women's medical roles continue to expand in the 17th century, especially regarding care of paupers. They operated nursing homes for the homeless and sick poor, and also looked after abandoned and orphaned children, pregnant women, and lunatics. After 1700, the workhouse movement undermined many of these roles and the parish nurse became restricted largely to the rearing and nursing of children and infants.[21]

Marriage

[edit]Over ninety per cent of English women (and adults, in general) entered marriage in this era at an average age of about 25–26 years for the bride and 27–28 years for the groom.[22] Among the nobility and gentry, the average was around 19-21 for brides and 24-26 for grooms.[23] Many city and townswomen married for the first time in their thirties and forties and it was not unusual for orphaned young women to delay marriage until the late twenties or early thirties to help support their younger siblings,[24] and roughly a fourth of all English brides were pregnant at their weddings.[25]

Witchcraft

[edit]

In England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland there was a succession of Witchcraft Acts starting with Henry VIII's Witchcraft Act 1541 (33 Hen. 8. c. 8). They governed witchcraft and providing penalties for its practice, or—in 1735—rather for pretending to practise it.

In Wales, fear of witchcraft mounted around the year 1500. There was a growing alarm of women's magic as a weapon aimed against the state and church. The Church made greater efforts to enforce the canon law of marriage, especially in Wales where tradition allowed a wider range of sexual partnerships. There was a political dimension as well, as accusations of witchcraft were levied against the enemies of Henry VII, who was exerting more and more control over Wales.[26]

The records of the Courts of Great Sessions for Wales, 1536-1736 show that Welsh custom was more important than English law. Custom provided a framework of responding to witches and witchcraft in such a way that interpersonal and communal harmony was maintained, Showing to regard to the importance of honour, social place and cultural status. Even when found guilty, execution did not occur.[27]

Becoming king in 1603, James I brought to England and Scotland continental explanations of witchcraft. He set out the much stiffer Witchcraft Act 1603 (1 Jas. 1. c. 12), which made it a felony under common law. One goal was to divert suspicion away from male homosociality among the elite, and focus fear on female communities and large gatherings of women. He thought they threatened his political power so he laid the foundation for witchcraft and occultism policies, especially in Scotland. The point was that a widespread belief in the conspiracy of witches and a witches' Sabbath with the devil deprived women of political influence. Occult power was supposedly a womanly trait because women were weaker and more susceptible to the devil.[28]

Enlightenment attitudes after 1700 made a mockery of beliefs in witches. The Witchcraft Act 1735 (9 Geo. 2. c. 5) marked a complete reversal in attitudes. Penalties for the practice of witchcraft as traditionally constituted, which by that time was considered by many influential figures to be an impossible crime, were replaced by penalties for the pretence of witchcraft. A person who claimed to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or cast spells, or discover the whereabouts of stolen goods, was to be punished as a vagrant and a con artist, subject to fines and imprisonment.[29]

Historians Keith Thomas and his student Alan Macfarlane revolutionised the study of witchcraft by combining historical research with concepts drawn from anthropology.[30][31][32] They argued that English witchcraft, like African witchcraft, was endemic rather than epidemic. Older women were the favorite targets because they were marginal, dependent members of the community and therefore more likely to arouse feelings of both hostility and guilt, and less likely to have defenders of importance inside the community. Witchcraft accusations were the village's reaction to the breakdown of its internal community, coupled with the emergence of a newer set of values that was generating psychic stress.[33]

Reformation

[edit]The Reformation closed the convents and monasteries, and called on former monks and nuns to marry. Lay women shared in the religiosity of the Reformation.[34] In Scotland the egalitarian and emotional aspects of Calvinism appealed to men and women alike. Historian Alasdair Raffe finds that, "Men and women were thought equally likely to be among the elect....Godly men valued the prayers and conversation of their female co-religionists, and this reciprocity made for loving marriages and close friendships between men and women." Furthermore, there was an increasingly intense relationship In the pious bonds between minister and his women parishioners. For the first time, laywomen gained numerous new religious roles, and took a prominent place in prayer societies.[35]

Industrial Revolution

[edit]

Women's historians have debated the impact of the Industrial Revolution and capitalism generally on the status of women.[36][37][38] Taking a pessimistic view, Alice Clark argued that when capitalism arrived in 17th century England, it made a negative impact on the status of women as they lost much of their economic importance. Clark argues that in 16th century England, women were engaged in many aspects of industry and agriculture. The home was a central unit of production and women played a vital role in running farms, and in operating some trades and landed estates. For example, they brewed beer, handled the milk and butter, raised chickens and pigs, grew vegetables and fruit, spun flax and wool into thread, sewed and patched clothing, and nursed the sick. Their useful economic roles gave them a sort of equality with their husbands. However, Clark argues, as capitalism expanded in the 17th century, there was more and more division of labour with the husband taking paid labour jobs outside the home, and the wife reduced to unpaid household work. Middle-class women were confined to an idle domestic existence, supervising servants; lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. Capitalism, therefore, had a negative effect on more powerful women.[39] In a more positive interpretation, Ivy Pinchbeck argues that capitalism created the conditions for women's emancipation.[40] Louise Tilly and Joan Wallach Scott have emphasised the continuity and the status of women, finding three stages in European history. In the preindustrial era, production was mostly for home use and women produce much of the needs of the households. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early industrialisation, the entire family depended on the collective wages of its members, including husband, wife and older children. The third or modern stage is the "family consumer economy," in which the family is the site of consumption, and women are employed in large numbers in retail and clerical jobs to support rising standards of consumption.[41]

19th century

[edit]Fertility

[edit]In the Victorian era, fertility rates increased in every decade until 1901, when the rates started evening out.[42] There are several reasons for the increase in birth rates. One is biological: with improving living standards, the percentage of women who were able to have children increased. Another possible explanation is social. In the 19th century, the marriage rate increased, and people were getting married at a very young age until the end of the century, when the average age of marriage started to increase again slowly. The reasons why people got married younger and more frequently are uncertain. One theory is that greater prosperity allowed people to finance marriage and new households earlier than previously possible. With more births within marriage, it seems inevitable that marriage rates and birth rates would rise together.[43]

The evening out of fertility rates at the beginning of the 20th century was mainly the result of a few big changes: availability of forms of birth control, and changes in people's attitude towards sex.[44]

Morality and religion

[edit]The Victorian era is famous for the Victorian standards of personal morality. Historians generally agree that the middle classes held high personal moral standards (and usually followed them), but have debated whether the working classes followed suit. Moralists in the late 19th century such as Henry Mayhew decried the slums for their supposed high levels of cohabitation without marriage and illegitimate births. However, new research using computerised matching of data files shows that the rates of cohabitation were quite low—under 5%—for the working class and the poor. By contrast in 21st century Britain, nearly half of all children are born outside marriage, and nine in ten newlyweds have been cohabitating.[45][46]

Historians have begun to analyse the agency of women in overseas missions. At first, missionary societies officially enrolled only men, but women increasingly insisted on playing a variety of roles. Single women typically worked as educators. Wives assisted their missionary husbands in most of his roles. Advocates stopped short of calling for the end of specified gender roles, but they stressed the interconnectedness of the public and private spheres and spoke out against perceptions of women as weak and house-bound.[47]

The middle-class

[edit]The middle class typically had one or more servants to handle cooking, cleaning and child care, Industrialisation brought with it a rapidly growing middle class whose increase in numbers had a significant effect on the social strata itself: cultural norms, lifestyle, values and morality. Identifiable characteristics came to define the middle-class home and lifestyle. Previously, in town and city, residential space was adjacent to or incorporated into the work site, virtually occupying the same geographical space. The difference between private life and commerce was a fluid one distinguished by an informal demarcation of function. In the Victorian era, English family life increasingly became compartmentalised, the home a self-contained structure housing a nuclear family extended according to need and circumstance to include blood relations. The concept of "privacy" became a hallmark of the middle class life.

The English home closed up and darkened over the decade (1850s), the cult of domesticity matched by a cult of privacy. Bourgeois existence was a world of interior space, heavily curtained off and wary of intrusion, and opened only by invitation for viewing on occasions such as parties or teas. "The essential, unknowability of each individual, and society's collaboration in the maintenance of a façade behind which lurked innumerable mysteries, were the themes which preoccupied many mid-century novelists."[48]

— Kate Summerscale quoting historian Anthony S. Wohl

Working-class families

[edit]Domestic life for a working-class family meant the housewife had to handle the chores servants did in wealthier families. A working-class wife was responsible for keeping her family as clean, warm, and dry as possible in housing stock that was often literally rotting around them. In London, overcrowding was endemic in the slums; a family living in one room was common.[49] Rents were high in London; half of working-class households paid one-quarter to one-half of their income on rent.

Domestic chores for women without servants meant a great deal of washing and cleaning. Coal-dust from home stoves and factories filled the city air, coating windows, clothing, furniture and rugs. Washing clothing and linens meant scrubbing by hand in a large zinc or copper tub. Some water would be heated and added to the wash tub, and perhaps a handful of soda to soften the water. Curtains were taken down and washed every fortnight; they were often so blackened by coal smoke that they had to be soaked in salted water before being washed. Scrubbing the front wooden doorstep of the home every morning was done to maintain respectability.[50]

Leisure

[edit]

Opportunities for leisure activities increased dramatically as real wages continued to grow and hours of work continued to decline. In urban areas, the nine-hour workday became increasingly the norm; the Factory Act 1874 limited the workweek to 56.5 hours, encouraging the movement toward an eventual eight-hour workday. Helped by the Bank Holiday Act 1871, which created a number of fixed holidays, a system of routine annual holidays came into play, starting with middle class workers and moving into the working-class.[51] Some 200 seaside resorts emerged thanks to cheap hotels and inexpensive railway fares, widespread banking holidays and the fading of many religious prohibitions against secular activities on Sundays. Middle-class Victorians used the train services to visit the seaside. Large numbers travelling to quiet fishing villages such as Worthing, Brighton, Morecambe and Scarborough began turning them into major tourist centres, and people like Thomas Cook saw tourism and even overseas travel as viable businesses.[52]

By the late Victorian era, the leisure industry had emerged in all cities with many women in attendance. It provided scheduled entertainment of suitable length at convenient locales at inexpensive prices. These included sporting events, music halls, and popular theatre. Women were now allowed in some sports, such as archery, tennis, badminton and gymnastics.[53]

Feminism and Reform

[edit]

The advent of Reformism during the 19th century opened new opportunities for reformers to address issues facing women and launched the feminist movement. The first organised movement for British women's suffrage was the Langham Place Circle of the 1850s, led by Barbara Bodichon (née Leigh-Smith) and Bessie Rayner Parkes. They also campaigned for improved female rights in the law, employment, education, and marriage.

Property owning women and widows had been allowed to vote in some local elections, but that ended in 1835. The Chartist Movement was a large-scale demand for suffrage—but it meant manhood suffrage. Upper-class women could exert a little backstage political influence in high society. However, in divorce cases, rich women lost control of their children.

Child custody

[edit]Before 1839, after divorce rich women lost control of their children as those children would continue in the family unit with the father, as head of the household, and who continued to be responsible for them. Caroline Norton was one such woman, her personal tragedy where she was denied access to her three sons after a divorce, led her to a life of intense campaigning which successfully led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act 1839 and then introduced the tender years doctrine for child custody arrangement.[54][55][56][57] The act gave women, for the first time, a right to their children and gave some discretion to the judge in a child custody cases. Under the doctrine the act also established a presumption of maternal custody for children under the age of seven years maintaining the responsibility for financial support to the father.[54] Due to additional pressure from women, the Parliament passed the Custody of Infants Act 1873 which extended the presumption of maternal custody until a child reached sixteen.[58][59] The doctrine spread in many states of the world because of the British Empire.[56]

Divorce

[edit]Traditionally, poor people used desertion, and (for poor men) even the practice of selling wives in the market, as a substitute for divorce.[60] In Britain before 1857 wives were under the economic and legal control of their husbands, and divorce was almost impossible. It required a very expensive private act of Parliament costing perhaps £200, of the sort only the richest could possibly afford. It was very difficult to secure divorce on the grounds of adultery, desertion, or cruelty. The first key legislative victory came with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. It passed over the strenuous opposition of the highly traditional Church of England. The new law made divorce a civil affair of the courts, rather than a Church matter, with a new civil court in London handling all cases. The process was still quite expensive, at about £40, but now became feasible for the middle class. A woman who obtained a judicial separation took the status of a feme sole, with full control of her own civil rights. Additional amendments came in 1878, which allowed for separations handled by local justices of the peace. The Church of England blocked further reforms until the final breakthrough came with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973.[61][62]

Protection

[edit]A series of four laws called the Married Women's Property Act passed Parliament from 1870 to 1882 that effectively removed the restrictions that kept wealthy married women from controlling their own property. They now had practically equal status with their husbands, and a status superior to women anywhere else in Europe.[63][64][65] Working-class women were protected by a series of laws passed on the assumption that they (like children) did not have full bargaining power and needed protection by the government.[66]

Prostitution

[edit]Bullough argues that prostitution in 18th-century Britain was a convenience to men of all social statuses, and economic necessity for many poor women, and was tolerated by society. The evangelical movement of the nineteenth century denounced the prostitutes and their clients as sinners, and denounced society for tolerating it.[67] Prostitution, according to the values of the Victorian middle-class, was a horrible evil, for the young women, for the men, and for all of society. Parliament in the 1860s in the Contagious Diseases Acts ("CD") adopted the French system of licensed prostitution. The "regulationist policy" was to isolate, segregate, and control prostitution. The main goal was to protect working men, soldiers and sailors near ports and army bases from catching venereal disease. Young women officially became prostitutes and were trapped for life in the system. After a nationwide crusade led by Josephine Butler and the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, Parliament repealed the acts and ended legalised prostitution. Butler became a sort of saviour to the girls she helped free. The age of consent for young women was raised from 12 to 16, undercutting the supply of young prostitutes who were in highest demand. The new moral code meant that respectable men dared not be caught.[68][69][70][71]

Work opportunities

[edit]The rapid growth of factories created job opportunities for unskilled and semiskilled women in light industries, such as textiles, clothing, and food production. There was an enormous popular and literary interest, as well as scientific interest, in the new status of women workers.[72] In Scotland St Andrews University pioneered the admission of women to universities, creating the Lady Licentiate in Arts (LLA), which proved highly popular. From 1892 Scottish universities could admit and graduate women and the numbers of women at Scottish universities steadily increased until the early 20th century.[73]

Middle-class careers

[edit]Ambitious middle-class women faced enormous challenges and the goals of entering suitable careers, such as nursing, teaching, law and medicine. The loftier their ambition, the greater the challenge. Physicians kept tightly shut the door to medicine; there were a few places for woman as lawyers, but none as clerics.[74]

In the 1870s a new employment role opened for women in libraries; it was said that the tasks were "Eminently Suited to Girls and Women." By 1920, women and men were equally numerous in the library profession, but women pulled ahead by 1930 and comprised 80% by 1960.[75] The factors accounting for the transition included the demographic losses of the First World War, the provisions of the Public Libraries Act of 1919, the library-building activity of the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, and the library employment advocacy of the Central Bureau for the Employment of Women.[76]

Teaching

[edit]Teaching was not quite as easy to break into, but the low salaries were less of a barrier to the single woman then to the married man. By the late 1860s a number of schools were preparing women for careers as governesses or teachers. The census reported in 1851 that 70,000 women in England and Wales were teachers, compared to the 170,000 who comprised three-fourths of all teachers in 1901.[77][78] The great majority came from lower middle class origins.[79] The National Union of Women Teachers (NUWT) originated in the early 20th century inside the male-controlled National Union of Teachers (NUT). It demanded equal pay with male teachers, and eventually broke away.[80] Oxford and Cambridge minimised the role of women, only allowing small all-female colleges to operate. However the new redbrick universities and the other major cities were open to women.[81]

Nursing and Medicine

[edit]Florence Nightingale demonstrated the necessity of professional nursing in modern warfare, and set up an educational system that tracked women into that field in the second half of the nineteenth century. Nursing by 1900 was a highly attractive field for middle-class women.[82][83]

Medicine was very well organised by men, and posed an almost insurmountable challenge for women, with the most systematic resistance by the physicians, and the fewest women breaking through. One route to entry was to go to the United States where there were suitable schools for women as early as 1850. Britain was the last major country to train female physicians, so 80 to 90% of British women with medical degrees got them in America. Edinburgh University admitted a few women in 1869, then reversed itself in 1873, leaving a strong negative reaction among British medical educators. The first separate school for female physicians opened in London in 1874 to a handful of students. In 1877, the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland became the first institution to take advantage of the Medical Act 1876 and admit women to take its medical licences. In all cases, coeducation had to wait until the World War.[84][85]

Poverty among working-class women

[edit]The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 defined who could receive monetary relief. The act reflected and perpetuated prevailing gender conditions. In Edwardian society, men were the source of wealth. The law restricted relief for unemployed, able-bodied male workers, due to the prevailing view that they would find work in the absence of financial assistance. However, women were treated differently. After the Poor Law was passed, women and children received most of the aid. The law did not recognise single independent women, and lumped women and children into the same category.[86] If a man was physically disabled, his wife was also treated as disabled under the law.[86] Unmarried mothers were sent to the workhouse, receiving unfair social treatment such as being restricted from attending church on Sundays.[86] During marriage disputes women often lost the rights to their children, even if their husbands were abusive.[86]

At the time, single mothers were the poorest sector in society, disadvantaged for at least four reasons. First, women had longer lifespans, often leaving them widowed with children. Second, women's work opportunities were few, and when they did find work, their wages were lower than male workers' wages. Third, women were often less likely to remarry after being widowed, leaving them as the main providers for the remaining family members.[86] Finally, poor women had deficient diets, because their husbands and children received disproportionately large shares of food. Many women were malnourished and had limited access to health care.[86]

20th century

[edit]Women in the Edwardian Era

[edit]The Edwardian era, from the 1890s to the First World War saw middle-class women breaking out of the Victorian limitations. Women had more employment opportunities and were more active. Many served worldwide in the British Empire or in Protestant missionary societies.

Housewives

[edit]For housewives, sewing machines enabled the production of ready made clothing and made it easier for women to sew their own clothes; more generally, argues Barbara Burman, "home dressmaking was sustained as an important aid for women negotiating wider social shifts and tensions in their lives."[87] An increased literacy in the middle class gave women wider access to information and ideas. Numerous new magazines appealed to her tastes and help define femininity.[88]

White-collar careers

[edit]The inventions of the typewriter, telephone, and new filing systems offered middle-class women increased employment opportunities.[89][90] So too did the rapid expansion of the school system,[91] and the emergence of the new profession of nursing. Education and status led to demands for female roles in the rapidly expanding world of sports.[92]

Women's suffrage

[edit]

As middle-class women rose in status they increasingly supported demands for a political voice.[93]

In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a suffrage advocacy organisation.[94] While WSPU was the most visible suffrage group, it was only one of many, such as the Women's Freedom League and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett. In Wales the suffragists women were attacked as outsiders and were usually treated with rudeness and often violence when they demonstrated or spoke publicly. The idea of Welshness was by then highly masculine because of its identification with labouring in heavy industry and mining and with militant union action.[95]

The radical protests steadily became more violent, and included heckling, banging on doors, smashing shop windows, burning mailboxes, and arson of unoccupied buildings. Emily Davison, a WSPU member, unexpectedly ran onto the track during the 1913 Epsom Derby and died under the King's horse. These tactics produced mixed results of sympathy and alienation. As many protesters were imprisoned and went on hunger-strike, the Liberal government was left with an embarrassing situation. From these political actions, the suffragists successfully created publicity around their institutional discrimination and sexism. Historians generally argue that the first stage of the militant suffragette movement under the Pankhursts in 1906 had a dramatic mobilising effect on the suffrage movement. Women were thrilled and supportive of an actual revolt in the streets; the membership of the militant WSPU and the older NUWSS overlapped and was mutually supportive. However a system of publicity, historian Robert Ensor argues, had to continue to escalate to maintain its high visibility in the media. The hunger strikes and force-feeding did that.[96] However the Pankhursts refused any advice and escalated their tactics. They turned to systematic disruption of Liberal Party meetings as well as physical violence in terms of damaging public buildings and arson. This went too far, as the overwhelming majority of moderate suffragists pulled back and refused to follow because they could no longer defend the tactics. They increasingly repudiated the extremists as an obstacle to achieving suffrage, saying the militant suffragettes were now aiding the antis, and many historians agree. Historian G. R. Searle says the methods of the suffragettes did succeed in damaging the Liberal party but failed to advance the cause of woman suffrage. When the Pankhursts decided to stop the militancy at the start of the war, and enthusiastically support the war effort, the movement split and their leadership role ended. Suffrage did come four years later, but the feminist movement in Britain permanently abandoned the militant tactics that had made the suffragettes famous.[97]

In Wales, women's participation in politics grew steadily from the start of the suffrage movement in 1907. By 2003, half the members elected to the National Assembly were women.[98]

Birth control

[edit]Although abortion was illegal, it was nevertheless the most widespread form of birth control in use.[99] Used predominantly by working-class women, the procedure was used not only as a means of terminating pregnancy, but also to prevent poverty and unemployment. Those who transported contraceptives could be legally punished.[99] Contraceptives became more expensive over time and had a high failure rate.[99] Unlike contraceptives, abortion did not need any prior planning and was less expensive. Newspaper advertisements were used to promote and sell abortifacients indirectly.[100]

Female servants

[edit]Edwardian Britain had large numbers of male and female domestic servants, in both urban and rural areas.[101] Men relied on working-class women to run their homes smoothly, and employers often looked to these working-class women for sexual partners.[101] Servants were provided with food, clothing, housing, and a small wage, and lived in a self-enclosed social system inside the mansion.[102] The number of domestic servants fell in the Edwardian period due to a declining number of young people willing to be employed in this area.[103]

Fashion

[edit]

The upper classes embraced leisure sports, which resulted in rapid developments in fashion, as more mobile and flexible clothing styles were needed.[104][105] During the Edwardian era, women wore a very tight corset, or bodice, and dressed in long skirts. The Edwardian era was the last time women wore corsets in everyday life. According to Arthur Marwick, the most striking change of all the developments that occurred during the Great War was the modification in women's dress, "for, however far politicians were to put the clocks back in other steeples in the years after the war, no one ever put the lost inches back on the hems of women's skirts".[106]

The Edwardians developed new styles in clothing design.[107] The bustle and heavy fabrics of the previous century disappeared. A new concept of tight fitting skirts and dresses made of lightweight fabrics were introduced for a more active lifestyle.[108]

- The 2 pieces dress came into vogue. Skirts hung tight at the hips and flared at the hem, creating a trumpet of lily-like shape.

- Skirts in 1901 had decorated hems with ruffles of fabric and lace.

- Some dresses and skirts featured trains.

- Tailored jackets, first introduced in 1880, increased in popularity and by 1900, tailored suits became popular.[109]

- By 1904, skirts became fuller and less clingy.

- In 1905, skirts fell in soft folds that curved in, then flared out near the hemlines.

- From 1905 - 1907, waistlines rose.

- In 1901, the hobble skirt was introduced; a tight fitting skirt that restricted a woman's stride.

- Lingerie dresses, or tea gowns made of soft fabrics, festooned with ruffles and lace were worn indoors.[110]

First World War

[edit]

The First World War advanced the feminist cause, as women's sacrifices and paid employment were much appreciated. Prime Minister David Lloyd George was clear about how important the women were:

It would have been utterly impossible for us to have waged a successful war had it not been for the skill and ardour, enthusiasm and industry which the women of this country have thrown into the war.[111]

The militant suffragette movement was suspended during the war and never resumed. British society credited the new patriotic roles women played as earning them the vote in 1918.[112] However, British historians no longer emphasise the granting of woman suffrage as a reward for women's participation in war work. Pugh (1974) argues that enfranchising soldiers primarily and women secondarily was decided by senior politicians in 1916. In the absence of major women's groups demanding for equal suffrage, the government's conference recommended limited, age-restricted women's suffrage. The suffragettes had been weakened, Pugh argues, by repeated failures before 1914 and by the disorganising effects of war mobilisation; therefore they quietly accepted these restrictions, which were approved in 1918 by a majority of the War Ministry and each political party in Parliament.[113] More generally, Searle (2004) argues that the British debate was essentially over by the 1890s, and that granting the suffrage in 1918 was mostly a byproduct of giving the vote to male soldiers. Women in Britain finally achieved suffrage on the same terms as men in 1928.[114]

There was a relaxing of clothing restrictions; by 1920 there was negative talk about young women called "flappers" flaunting their sexuality.[115]

Social reform

[edit]The vote did not immediately change social circumstances. With the economic recession, women were the most vulnerable sector of the workforce. Some women who held jobs prior to the war were obliged to forfeit them to returning soldiers, and others were excessed. With limited franchise, the UK National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) pivoted into a new organisation, the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC),[116] which still advocated for equality in franchise, but extended its scope to examine equality in social and economic areas. Legislative reform was sought for discriminatory laws (e.g., family law and prostitution) and over the differences between equality and equity, the accommodations that would allow women to overcome barriers to fulfillment (known in later years as the "equality vs. difference conundrum").[117] Eleanor Rathbone, who became an MP in 1929, succeeded Millicent Garrett as president of NUSEC in 1919. She expressed the critical need for consideration of difference in gender relationships as "what women need to fulfill the potentialities of their own natures".[118] The 1924 Labour government's social reforms created a formal split, as a splinter group of strict egalitarians formed the Open Door Council in May 1926.[119] This eventually became an international movement, and continued until 1965. Other important social legislation of this period included the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 (which opened professions to women), and the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923. In 1932, NUSEC separated advocacy from education, and continued the former activities as the National Council for Equal Citizenship and the latter as the Townswomen's Guild. The council continued until the end of the Second World War.[120]

Reproductive rights

[edit]Annie Besant had been prosecuted in 1877 for publishing Charles Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy, a work on family planning, under the Obscene Publications Act 1857.[121][122] Knowlton had previously been convicted in the United States for publishing a book on conception. She and her colleague Charles Bradlaugh were convicted but acquitted on appeal, the subsequent publicity resulting in a decline in the birth rate.[123][124] Besant followed this with The Law of Population.[125]

Second World War

[edit]

Britain's total mobilisation during this period proved to be successful in winning the war, by maintaining strong support from public opinion. The war was a "people's war" that enlarged democratic aspirations and produced promises of a postwar welfare state.[126][127]

Historians credit Britain with a highly successful record of mobilising the home front for the war effort, in terms of mobilising the greatest proportion of potential workers, maximising output, assigning the right skills to the right task, and maintaining the morale and spirit of the people.[128] Much of this success was due to the systematic planned mobilisation of women, as workers, soldiers and housewives, enforced after December 1941 by conscription.[129] The women supported the war effort, and made the rationing of consumer goods a success. In some ways, the government over planned, evacuating too many children in the first days of the war, closing cinemas as frivolous then reopening them when the need for cheap entertainment was clear, sacrificing cats and dogs to save a little space on shipping pet food, only to discover an urgent need to keep the rats and mice under control.[130] In the balance between compulsion and voluntarism, the British relied successfully on voluntarism. The success of the government in providing new services, such as hospitals, and school lunches, as well as the equalitarian spirit of the People's war, contributed to widespread support for an enlarged welfare state. Munitions production rose dramatically, and the quality remained high. Food production was emphasised, in large part to open up shipping for munitions. Farmers increased the number of acres under cultivation from 12,000,000 to 18,000,000, and the farm labor force was expanded by a fifth, thanks especially to the Women's Land Army.[131][132]

Parents had much less time for supervision of their children, and the fear of juvenile delinquency was upon the land, especially as older teenagers took jobs and emulated their older siblings in the service. The government responded by requiring all youth over 16 to register, and expanded the number of clubs and organisations available to them.[133]

Rationing

[edit]

Food, clothing, petrol, leather and other such items were rationed. However, items such as sweets and fruits were not rationed, as they would spoil. Access to luxuries was severely restricted, although there was also a significant black market. Families also grew victory gardens, and small home vegetable gardens, to supply themselves with food. Many things were conserved to turn into weapons later, such as fat for nitroglycerin production. People in the countryside were less affected by rationing as they had greater access to locally sourced unrationed products than people in metropolitan areas and were more able to grow their own.

The rationing system, which had been originally based on a specific basket of goods for each consumer, was much improved by switching to a points system which allowed the housewives to make choices based on their own priorities. Food rationing also permitted the upgrading of the quality of the food available, and housewives approved—except for the absence of white bread and the government's imposition of an unpalatable wheat meal "national loaf." People were especially pleased that rationing brought equality and a guarantee of a decent meal at an affordable cost.[131]

1950s

[edit]1950s Britain was a bleak period for militant feminism. In the aftermath of World War II, a new emphasis was placed on companionate marriage and the nuclear family as a foundation of the new welfare state.[134][135]

In 1951, the proportion of adult women who were (or had been) married was 75%; more specifically, 84.8% of women between the ages of 45 and 49 were married.[136] At that time: "marriage was more popular than ever before."[137] In 1953, a popular book of advice for women states: "A happy marriage may be seen, not as a holy state or something to which a few may luckily attain, but rather as the best course, the simplest, and the easiest way of life for us all".[138]

While at the end of the war, childcare facilities were closed and assistance for working women became limited, the social reforms implemented by the new welfare state included family allowances meant to subsidise families, that is, to support women in the "capacity as wife and mother."[135] Sue Bruley argues that "the progressive vision of the New Britain of 1945 was flawed by a fundamentally conservative view of women".[139]

Women's commitment to companionate marriage was echoed by the popular media: films, radio and popular women's magazines. In the 1950s, women's magazines had considerable influence on forming opinion in all walks of life, including the attitude to women's employment.

Nevertheless, 1950s Britain saw several strides towards the parity of women, such as equal pay for teachers (1952) and for men and women in the civil service (1954), thanks to activists like Edith Summerskill, who fought for women's causes both in parliament and in the traditional non-party pressure groups throughout the 1950s.[140] Barbara Caine argues: "Ironically here, as with the vote, success was sometimes the worst enemy of organised feminism, as the achievement of each goal brought to an end the campaign which had been organised around it, leaving nothing in its place."[141]

Feminist writers of that period, such as Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to allow for the possibility that women should be able to combine home with outside employment. 1950s’ form of feminism is often derogatorily termed "welfare feminism."[142] Indeed, many activists went to great length to stress that their position was that of ‘reasonable modern feminism,’ which accepted sexual diversity, and sought to establish what women's social contribution was rather than emphasising equality or the similarity of the sexes. Feminism in 1950s England was strongly connected to social responsibility and involved the well-being of society as a whole. This often came at the cost of the liberation and personal fulfillment of self-declared feminists. Even those women who regarded themselves as feminists strongly endorsed prevailing ideas about the primacy of children's needs, as advocated, for example, by John Bowlby the head of the Children's Department at the Tavistock Clinic, who published extensively throughout the 1950s and by Donald Winnicott who promoted through radio broadcasts and in the press the idea of the home as a private emotional world in which mother and child are bound to each other and in which the mother has control and finds freedom to fulfill herself.[143]

Political and sexual roles

[edit]

Women's political roles grew in the 20th century after the first woman entered the House in 1919. The 1945 election trebled their number to twenty-four, but then it plateaued out. The next great leap came in 1997, as 120 female MPs were returned. Women have since comprised around 20 per cent of the Commons. The 2015 election saw a peak of 191 elected.[144] The BBC radio program "Woman's Hour" was launched in 1946. The producers recognised that its audience wanted coverage of fashion and glamour, as well as housekeeping, family health and child rearing. Nevertheless, it tried to enhance the sense of citizenship among its middle class audience;. In cooperation with organisations, such as the National Council of Women (NCW), the National Federation of Women's Institutes (NFWI), and the National Union of Townswomen's Guilds (NUTG), the program featured coverage of current affairs, public debates and national politics; it gave play to party political conferences; and it brought women MP's to the microphone.[145]

The 1960s saw dramatic shifts in sexual attitudes and values, led by youth.[146] It was a worldwide phenomenon, in which British rock musicians especially The Beatles played an international role.[147] The generations divided sharply regarding the new sexual freedom demanded by youth who listened to bands like The Rolling Stones.[148]

Sexual morals changed. One notable event was the publication of D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover by Penguin Books in 1960. Although first printed in 1928, the release in 1960 of an inexpensive mass-market paperback version prompted a court case. The prosecuting council's question, "Would you want your wife or servants to read this book?" highlighted how far society had changed, and how little some people had noticed. The book was seen as one of the first events in a general relaxation of sexual attitudes. Other elements of the sexual revolution included the development of The Pill, Mary Quant's miniskirt and the 1967 legalisation of homosexuality. There was a rise in the incidence of divorce and abortion, and a resurgence of the women's liberation movement, whose campaigning helped secure the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. The Irish Catholics, traditionally the most puritanical of the ethno-religious groups, eased up a little, especially as the membership disregarded the bishops teaching that contraception was sinful.[149]

21st century

[edit]

From 2007 to 2015, Harriet Harman was Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, the UK's current party in government. Traditionally, being Deputy Leader has ensured the cabinet role of Deputy Prime Minister. However, Gordon Brown announced that he would not have a Deputy Prime Minister, much to the consternation of feminists,[150] particularly with suggestions that privately Brown considered Jack Straw to be de facto deputy prime minister[151] and thus bypassing Harman. With Harman's cabinet post of Leader of the House of Commons, Brown allowed her to chair Prime Minister's Questions when he was out of the country. Harman also held the post Minister for Women and Equality. In April 2012 after being sexually harassed on London public transport English journalist Laura Bates founded the Everyday Sexism Project, a website which documents everyday examples of sexism experienced by contributors from around the world. The site quickly became successful and a book compilation of submissions from the project was published in 2014. In 2013, the first oral history archive of the United Kingdom women's liberation movement (titled Sisterhood and After) was launched by the British Library.[152]

Across all occupations, men are still paid more than women, but the gap has steadily narrowed. In 2024, women were paid 91p for every £1 a man earns; the gap is highest in the public sector.[153] In 2025, women doctors in the UK for the first time outnumber men in the 330,000-strong medical workforce, according to the General Medical Council (GMC).[154]

See also

[edit]Topics

[edit]- Abortion in the United Kingdom

- Economic history of the United Kingdom, after 1700

- Feminism in the United Kingdom

- Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- List of female members of the House of Lords

- Social history of England

- Social history of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

- Suffrage in the United Kingdom

- The Women's Peace Crusade

- Timeline of Female MPs in the House of Commons

- Women in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

- Women in the House of Lords

- Women in the Victorian era

- Women in World War I (Great Britain)

- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

Scotland

[edit]Wales

[edit]Categories

[edit]- British suffragists

- British women

- English women

- Scottish women

- Welsh women

- Women from Northern Ireland

- Women in Scotland

Organisations

[edit]- British Federation of University Women (BFUW), founded in 1907.

- NASUWT, The National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers, formed 1976

- National Council of Women of Great Britain

- National Union of Women Teachers, formed 1904

- Adelaide Anne Procter (1825–1864) writer on behalf of unemployed women

- Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps, unit in First World War

- Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW), formed 1859; in 1926 renamed the Society for Promoting the Training of Women (SPTW)

- Townswomen's Guild, formed 1929

- Women's Freedom League

- Women's Institutes

- Scottish Women's Institutes, formed in 1917

- Women's Social and Political Union, suffragists of early 20th century

Individuals

[edit]- Margaret Bondfield (1873–1953) women's rights activist

- Edith Balfour Lyttelton (1865–1948) novelist, activist and spiritualist.

- Mary Macarthur (1880–1921) trade unionist and women's rights campaigner.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2021" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Mate, Mavis E. (2006), "Introduction", in Mate, Mavis (ed.), Trade and economic developments, 1450-1550: the experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex, Woodbridge, UK Rochester, New York: Boydell Press, pp. 2–7, ISBN 9781843831891.

- ^ Mate, Mavis (2006), "Overseas trade", in Mate E., Mavis (ed.), Trade and economic developments, 1450-1550: the experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex, Woodbridge, UK Rochester, New York: Boydell Press, pp. 97–99, ISBN 9781843831891.

- ^ Johns, Susan M. (2003), "Power and portrayal", in Johns, Susan M. (ed.), Noblewomen, aristocracy, and power in the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman realm, Manchester New York: Manchester University Press, p. 14, ISBN 9780719063053.

- ^ Leyser, Henrietta (1996). Medieval women: a social history of women in England, 450-1500. London: Phoenix Giant. ISBN 9781842126219.

- ^ Mate, Mavis E. (2006), "Trade within and outside the Market-Place", in Mate, Mavis (ed.), Trade and economic developments, 1450-1550: the experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex, Woodbridge, UK Rochester, New York: Boydell Press, pp. 21–27, ISBN 9781843831891.

- ^ Johns, Susan M. (2003). Noblewomen, aristocracy, and power in the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman realm. Manchester New York: Manchester University Press. pp. 22–25, 30, 69, 195–96 14. ISBN 9780719063053.

- ^ Bennett, Judith M. (1999). Ale, beer and brewsters in England: women's work in a changing world, 1300-1600. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195073904.

- ^ Weinstein, Minna F. (1978). "Reconstructing our past: reflections on Tudor women". International Journal of Women's Studies. 1 (2). Eden Press Women's Publications: 133–158.

- ^ On the social and demographic history see: Palliser, D. M. (2013). The age of Elizabeth: England under the later Tudors, 1547-1603 (2nd ed.). Oxfordshire, England New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781315846750.

- ^ Shapiro, Susan C. (1977). "Feminists in Elizabethan England". History Today. 27 (11): 703–711.

- ^ Youings, Joyce A. (1984). Sixteenth-century England. London: A. Lane. ISBN 9780713912432.

- ^ John N. King (1990). "Queen Elizabeth I: Representations of the Virgin Queen". Renaissance Quarterly. 43 (1): 30–74. doi:10.2307/2861792. JSTOR 2861792. S2CID 164188105.

- ^ Haigh, Christopher (1998), "The Queen and the throne", in Haigh, Christopher (ed.), Elizabeth I (2nd ed.), London New York: Longman, p. 23, ISBN 9780582437548.

- ^ Doran, Susan (June 1995). "Juno versus Diana: The treatment of Elizabeth I's marriage in plays and entertainments, 1561–1581". The Historical Journal. 38 (2). Cambridge Journals: 257–274. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00019427. JSTOR 2639984. S2CID 55555610.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes (1910), "Elizabeth", in Strickland, Agnes, ed. (1910). The life of Queen Elizabeth. London / New York: J.M. Dent / E.P. Dutton. p. 424. OCLC 1539139.

- ^ Cowen Orlin, Lena (1995), "The fictional families of Elizabeth I", in Levin, Carole; Sullivan, Patricia Ann (eds.), Political rhetoric, power, and Renaissance women, Albany: State University of New York Press, p. 90, ISBN 9780791425466.

- ^ Coch, Christine (Autumn 1996). ""Mother of my Contreye": Elizabeth I and Tudor construction of motherhood". English Literary Renaissance. 26 (3). University of Chicago Press: 423–450. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6757.1996.tb01506.x. JSTOR 43447529. S2CID 144685288.

- ^ Harkness, Deborah E. (Spring 2008). "A view from the streets: women and medical work in Elizabethan London". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 82 (1). Johns Hopkins University: 52–85. doi:10.1353/bhm.2008.0001. PMID 18344585. S2CID 5695475.

- ^ Boulton, Jeremy (2007). "Welfare systems and the parish nurse in early modern London, 1650–1725". Family & Community History. 10 (2). Taylor and Francis: 127–151. doi:10.1179/175138107x234413. S2CID 144158931.

- ^ Cressy, David (1997), "Holy matrimony", in Cressy, David (ed.), Birth, marriage, and death: ritual, religion, and the life-cycle in Tudor and Stuart England, Oxford England New York: Oxford University Press, p. 285, ISBN 9780198201687.

- ^ Young, Bruce W. (2009). "Family life in Shakespeare's world". In Young, Bruce W. (ed.). Family life in the age of Shakespeare. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780313342394.

- ^ Greer, Germaine (2009). Shakespeare's wife. Toronto: Emblem Editions. ISBN 9780771035838.

- ^ Cressy, David (1997), "Childbed attendants", in Cressy, David (ed.), Birth, marriage, and death: ritual, religion, and the life-cycle in Tudor and Stuart England, Oxford England New York: Oxford University Press, p. 74, ISBN 9780198201687.

- ^ Kamerick, Kathleen (Spring 2013). "Tanglost of Wales: magic and adultery in the Court of Chancery circa 1500". Sixteenth Century Journal. 44 (1). Truman State University: 25–45. doi:10.1086/SCJ24245243. S2CID 155334943.

- ^ Parkin, Sally (August 2006). "Witchcraft, women's honour and customary law in early modern Wales". Social History. 31 (3). Taylor and Francis: 295–318. doi:10.1080/03071020600746636. JSTOR 4287362. S2CID 143731691.

- ^ Lolis, Thomas G. (Summer 2008). "The City of Witches: James I, the Unholy Sabbath, and the homosocial refashioning of the witches' community" (PDF). Clio: A Journal of Literature, History, and the Philosophy of History. 37 (3). Indiana University, Purdue University and Fort Wayne: 322–337. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2014.

- ^ Henderson, Lizanne (2016), "Appendix II: The Witchcraft Act, 1735", in Henderson, Lizanne, ed. (2016). Witchcraft and folk belief in the age of enlightenment: Scotland 1670-1740. Basingstoke, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 330–331. ISBN 9781137313249.

- ^ Thomas, Keith (1971). Religion and the decline of magic: studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9780297819721.

- ^ Barry, Jonathan (1996), "Introduction: Keith Thomas and the problem of witchcraft", in Barry, Jonathan; Hester, Marianne; Roberts, Gareth (eds.), Witchcraft in early modern Europe: studies in culture and belief, Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–46, ISBN 9780521552240.

- ^ MacFarlane, Alan (1970). Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: a regional and comparative study. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780710064035.

- ^ Garrett, Clarke (Winter 1977). "Women and witches: patterns of analysis". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 3 (2). Chicago Journals: 461–470. doi:10.1086/493477. JSTOR 3173296. PMID 21213644. S2CID 143859863.

- ^ Carlson, Eric Josef (1994). Marriage and the English Reformation. Oxford, UK Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell. ISBN 9780631168645.

- ^ Raffe, Alasdair (2014), "Female authority and lay activism in Scottish Presbyterianism, 1660–1740", in Apetrei, Sarah; Smith, Hannah (eds.), Religion and women in Britain, c. 1660-1760, Farnham Surrey, England Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, pp. 61–78, ISBN 9781409429197.

- ^ Klein, Laura; Brusco, Elizabeth (1998), "Benedict, Ruth 1887 - 1948", in Amico, Eleanor, ed. (1998). Reader's guide to women's studies. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 102–104. ISBN 9781884964770.

- ^ Dickson, Carol E. (1998), "Eddy, Mary Baker 1821 - 1910", in Amico, Eleanor, ed. (1998). Reader's guide to women's studies. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 305–308. ISBN 9781884964770.

- ^ Thomas, Janet (July 1988). "Women and capitalism: oppression or emancipation? A review article". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 30 (3). Cambridge Journals: 534–549. doi:10.1017/S001041750001536X. JSTOR 178999. S2CID 145599586.

- ^ Clark, Alice (1919). "The working life of women in the seventeenth century". London: Routledge. OCLC 459278936.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pinchbeck, Ivy (2014) [1930]. Women workers and the industrial revolution 1750-1850. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138874633.

- ^ Tilly, Louise; Wallach Scott, Joan (1987). Women, work, and family. New York: Methuen. ISBN 9780416016819.

- ^ Szreter, Simon (2002). Fertility, class, and gender in Britain, 1860-1940. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521528689.

- ^ Woods, Robert I. (July 1987). "Approaches to the fertility transition in Victorian England". Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. 41 (2). Taylor and Francis: 283–311. doi:10.1080/0032472031000142806. JSTOR 2174178. PMID 11621339.

- ^ Knowlton, Charles (October 1891) [1840]. Besant, Annie; Bradlaugh, Charles (eds.). Fruits of philosophy: a treatise on the population question. San Francisco: Reader's Library. OCLC 626706770. A publication about birth control. View original copy.

- ^ Probert, Rebecca (October 2012). "Living in sin". BBC History Magazine.

- ^ Frost, Ginger (2011). Living in sin. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719085697.

- ^ Midgley, Clare (April 2006). "Can women be missionaries? Envisioning female agency in the early Nineteenth-century British Empire". Journal of British Studies. 45 (2). Cambridge Journals: 335–358. doi:10.1086/499791. JSTOR 10.1086/499791. S2CID 162512436.

- ^ Wohl, Anthony S. (1978). The Victorian family: structure and stresses. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 9780856644382.

- Cited in: Summerscale, Kate (2008). The suspicions of Mr. Whicher or the murder at Road Hill House. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9780747596486. (novel)

- ^ Wise, Sarah (2009), "Dead letters: the empire of hunger", in Wise, Sarah (ed.), The blackest streets: the life and death of a Victorian slum, London: Vintage, p. 6, ISBN 9781844133314

- ^ Murray, Janet Horowitz (1984), "Domestic life in poverty", in Murray, Janet Horowitz (ed.), Strong-minded women: and other lost voices from nineteenth-century England, Aylesbury: Penguin Books, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Searle, G. R. (2004), "The pursuit of pleasure", in Searle, G. R., ed. (2004). A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918. Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press. pp. 529–570. ISBN 9780198207146.

- ^ Walton, John K. (1983). The English seaside resort: a social history, 1750-1914. Leicester Leicestershire New York: Leicester University Press St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312255275.

- ^ Searle, G. R. (2004), "The pursuit of pleasure", in Searle, G. R., ed. (2004). A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918. Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press. pp. 547–553. ISBN 9780198207146.

- ^ a b Wroath, John (2006). Until they are seven: the origins of women's legal rights. Winchester England: Waterside Press. ISBN 9781872870571.

- ^ Mitchell, L. G. (1997). Lord Melbourne, 1779-1848. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198205920.

- ^ a b Perkins, Jane Gray (2013) [1909]. Life of the honourable Mrs. Norton. London: Theclassics Us. ISBN 9781230408378.

- ^ Hilton, Boyd (2006), "Ruling ideologies: the status of women and ideas about gender", in Hilton, Boyd (ed.), A mad, bad, and dangerous people?: England, 1783-1846, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 353–355, ISBN 9780198228301.

- ^ Lehman, Jeffrey; Phelps, Shirelle (2011). West's Encyclopedia of American Law, Vol. 9. Detroit: Thomson/Gale. p. 458. ISBN 9780787663766.

- ^ Katz, Sanford N. (1992). ""That they may thrive" goal of child custody: reflections on the apparent erosion of the tender years presumption and the emergence of the primary caretaker presumptions". Journal of Contemporary Health Law and Policy. 8 (1). Columbus School of Law, The Catholic University of America.

- ^ Stone, Lawrence (1990), "Desertion, elopement, and wife-sale", in Stone, Lawrence (ed.), Road to divorce: England 1530-1987, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 143–148, ISBN 9780198226512. Available online.

- ^ Stone (1990). Stone, Lawrence (ed.). Road to divorce: England 1530-1987. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198226512.

- ^ Halévy, Élie (1934), A history of the English people, London: Ernest Benn, OCLC 504342781

- ^ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 495–496. OCLC 504342781.

- ^ Griffin, Ben (March 2003). "Class, gender, and liberalism in Parliament, 1868–1882: the case of the Married Women's Property Acts". The Historical Journal. 46 (1). Cambridge Journals: 59–87. doi:10.1017/S0018246X02002844. S2CID 159520710.

- ^ Lyndon Shanley, Mary (Autumn 1986). "Suffrage, protective labor legislation, and Married Women's Property Laws in England". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 12 (1). Chicago Journals: 62–77. doi:10.1086/494297. JSTOR 3174357. S2CID 144723898.

- ^ Feurer, Rosemary (Winter 1988). "The meaning of "sisterhood": the British Women's Movement and protective labor legislation, 1870-1900". Victorian Studies. 31 (2). Indiana University Press: 233–260. JSTOR 3827971.

- ^ Bullough, Vern L. (1985). "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England". Eighteenth-Century Life. 9 (3): 61–74. ISBN 9780521347686.

- Also available as: Bullough, Vera L. (1987), "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England", in Maccubbin, Robert P., ed. (1987). Tis nature's fault: unauthorized sexuality during the Enlightenment. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–74. ISBN 9780521347686.

- ^ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 498–500. OCLC 504342781.

- ^ Strachey, Ray; Strachey, Barbara (1978). The cause: a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. London: Virago. pp. 187–222. ISBN 9780860680420.

- ^ Bartley, Paula (2000). Prostitution: prevention and reform in England, 1860-1914. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415214575.

- ^ Smith, F.B. (August 1990). "The Contagious Diseases Acts reconsidered". Social History of Medicine. 3 (2). Oxford Journals: 197–215. doi:10.1093/shm/3.2.197. PMID 11622578.

- ^ Neff, Wanda F. (2014). Victorian Working Women. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415759335.

- ^ Rayner-Canham, Marelene M.; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey W. (2008), "Universities in Scotland and Wales: entry of women to Scottish universities", in Rayner-Canham, Marelene M.; Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey W. (eds.), Chemistry was their life: pioneering British women chemists, 1880-1949, London Hackensack, New Jersey: Imperial College Press, p. 264, ISBN 9781860949869.

- ^ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 500–506. OCLC 504342781.

- ^ Kerslake, Evelyn (2007). "'They have had to come down to the women for help!'Numerical feminization and the characteristics of women's library employment in England, 1871–1974". Library History. 23 (1). Taylor and Francis: 17–40. doi:10.1179/174581607x177466. S2CID 145522426.

- ^ Coleman, Sterling Joseph Jr. (2014). "'Eminently suited to girls and women': the numerical feminization of public librarianship in England 1914–31". Library & Information History. 30 (3). Taylor and Francis: 195–209. doi:10.1179/1758348914Z.00000000063. S2CID 218688858.

- ^ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. p. 500. OCLC 504342781.

- ^ Copelman, Dina (2014). London's women teachers: gender, class and feminism, 1870-1930. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415867528.

- ^ Coppock, David A. (1997). "Respectability as a prerequisite of moral character: the social and occupational mobility of pupil teachers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries". History of Education. 26 (2). Taylor and Francis: 165–186. doi:10.1080/0046760970260203.

- ^ Owen, Patricia (1988). "Who would be free, herself must strike the blow". History of Education. 17 (1). Taylor and Francis: 83–99. doi:10.1080/0046760880170106.

- ^ Tamboukou, Maria (2000). "Of Other Spaces: Women's colleges at the turn of the nineteenth century in the UK" (PDF). Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. 7 (3). Taylor and Francis: 247–263. doi:10.1080/713668873. S2CID 144093378.

- ^ Hawkins, Sue (2010). Nursing and women's labour in the nineteenth century: the quest for independence. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415539746.

- ^ Helmstadter, Carol; Godden, Judith (2011). Nursing before Nightingale, 1815-1899. Farnham, Surrey, England Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781409423140.

- ^ Bonner, Thomas Neville (1995), "The fight for coeducation in Britain", in Bonner, Thomas Neville (ed.), To the ends of the earth: women's search for education in medicine, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pp. 120–137, ISBN 9780674893047.

- ^ Kelly, Laura (2013). "'The turning point in the whole struggle': the admission of women to the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland". Women's History Review. 22 (1). Taylor and Francis: 97–125. doi:10.1080/09612025.2012.724916. S2CID 143467317.

- ^ a b c d e f Thane, Pat (Autumn 1978). "Women and the Poor Law in Victorian and Edwardian England". History Workshop Journal. 6 (1). Oxford Journals: 29–51. doi:10.1093/hwj/6.1.29.

- ^ Burman, Barbara (1999), "Made at home by clever fingers: home dressmaking in Edwardian England", in Burman, Barbara (ed.), The culture of sewing: gender, consumption, and home dressmaking, Oxford New York: Berg, p. 34, ISBN 9781859732083.

- ^ Beetham, Margaret (1996). A magazine of her own?: domesticity and desire in the woman's magazine, 1800-1914. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415141123.

- ^ Wilson, Guerriero R. (2001). "Women's work in offices and the preservation of men's 'breadwinning'jobs in early twentieth-century Glasgow". Women's History Review. 10 (3). Taylor and Francis: 463–482. doi:10.1080/09612020100200296. PMID 19678416. S2CID 29861500.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory (1988). The White-blouse revolution: female office workers since 1870. Manchester, UK New York, New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719024009.

- ^ Dyhouse, Carol (2013). Girls growing up in late Victorian and Edwardian England. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138008045.

- ^ Parratt, Cartriona M. (1989). "Athletic 'Womanhood': Exploring sources for female sport in Victorian and Edwardian England" (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 16 (2). North American Society for Sport History: 140–157.

- ^ Pugh, Martin (1980). Women's suffrage in Britain, 1867-1928. London: Historical Association. ISBN 9780852782255.

- ^ Phillips, Melanie (2004). The ascent of woman: a history of the suffragette movement. London: Abacus. ISBN 9780349116600.

- ^ John, Angela V. (1994). "'Run Like Blazes' the Suffragettes and Welshness". Llafur. 6 (3). Llafur: The Welsh People's History Society: 29–43. hdl:10107/1328679.

- ^ Ensor, Robert C.K. England: 1870-1914. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 389–399. OCLC 24731395.

- ^ Searle, G. R. (2004), "The years of 'crisis', 1908-1914: The woman's revolt", in Searle, G. R. (ed.), A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918, Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, pp. 456–470, ISBN 9780198207146. Quote pp. 468.

- ^ Beddoe, Deirdre (2004). "Women and politics in Twentieth Century Wales". National Library of Wales Journal. 33 (3). National Library of Wales: 333–347. hdl:10107/1292074.

- ^ a b c Knight, Patricia (Autumn 1977). "Women and abortion in Victorian and Edwardian England". History Workshop Journal. 4 (1). Oxford Journals: 57–69. doi:10.1093/hwj/4.1.57. PMID 11610301.

- ^ McLaren, Angus (Summer 1977). "Abortion in England, 1890-1914". Victorian Studies. 20 (4). Indiana University Press: 379–400. JSTOR 3826710.

- ^ a b Benson, John (December 2007). "One man and his women: domestic service in Edwardian England". Labour History Review. 72 (3). Liverpool University Press: 203–214. doi:10.1179/174581607X264793. Pdf.

- ^ Davidoff, Leonore (Summer 1974). "Mastered for life: servant and wife in Victorian and Edwardian England". Journal of Social History. 7 (4). Oxford Journals: 406–428. doi:10.1353/jsh/7.4.406. JSTOR 3786464.

- ^ Pooley, Siân (May 2009). "Domestic servants and their urban employers: a case study of Lancaster, 1880–1914". The Economic History Review. 62 (2). Wiley: 405–429. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2008.00459.x. JSTOR 20542918. S2CID 153704509.

- ^ Constanzo, Marilyn (2002). "'One can't shake off the women': images of sport and gender in Punch, 1901-10". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 19 (1). Taylor and Francis: 31–56. doi:10.1080/714001704. PMID 20373549. S2CID 12158690.

- ^ Cosbey, Sarah; Damhorst, Mary Lynn; Farrell-Beck, Jane (June 2003). "Diversity of daytime clothing styles as a reflection of women's social role ambivalence from 1873 through 1912". Clothing & Textiles Research Journal. 21 (3). SAGE: 101–119. doi:10.1177/0887302X0302100301. S2CID 146780356.

- ^ Marwick, Arthur (1991), "New women:1915-1916", in Marwick, Arthur (ed.), The deluge: British society and the First World War (2nd ed.), Basingstoke: Macmillan, p. 151, ISBN 9780333548479.

- ^ Olian, JoAnne (1998). Victorian and Edwardian fashions from "La Mode Illustrée. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486297118.

- ^ Presley, Ann Beth (December 1998). "Fifty years of change: societal attitudes and women's fashions, 1900–1950". The Historian. 60 (2). Wiley: 307–324. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1998.tb01396.x.

- ^ Harris, Kristina (1995). Victorian & Edwardian fashions for women, 1840 to 1919. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9780887408427.

- ^ Edwards, Sarah (March 2012). "'Clad in robes of virgin white': the sexual politics of the 'lingerie' dress in novel and film versions of The Go-Between". Adaptation: A Journal of Literature on Screen Studies. 5 (1). Oxford Journals: 18–34. doi:10.1093/adaptation/apr002.

- ^ Whitfield, Bob (2001), "How did the First World War affect the campaign for women's suffrage?", in Whitfield, Bob, ed. (2001). The extension of the franchise, 1832-1931. Oxford: Heinemann Educational. p. 167. ISBN 9780435327170.

- ^ Taylor, A.J.P. (1965). English History, 1914-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 29, 94. OCLC 185566309.

- ^ Pugh, Martin D. (October 1974). "Politicians and the woman's vote 1914–1918". History. 59 (197). Wiley: 358–374. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1974.tb02222.x. JSTOR 24409414.

- ^ Searle, G. R. (2004), "War and the reshaping of identities: gender and generation", in Searle, G. R. (ed.), A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918, Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, p. 791, ISBN 9780198207146.

- ^ Langhamer, Claire (2000), "'Stepping out with the young set': youthful freedom and independence", in Langhamer, Claire, ed. (2000). Women's leisure in England, 1920-60. Manchester New York: Manchester University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780719057373.

- ^ "Strand 2: Women's Suffrage Societies (2NSE Records of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship)". twl-calm.library.lse.ac.uk. The Women's Library @ London School of Economics.

- ^ Offen, Karen (Summer 1995). "Women in the western world". Journal of Women's Studies. 7 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 145–151. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0359. S2CID 144349823.

- ^ Wayne, Tiffany K. (2011), ""The Old and the New Feminism" (1925) by Eleanor Rathbone", in Wayne, Tiffany K., ed. (2011). Feminist writings from ancient times to the modern world: a global sourcebook and history. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. pp. 484–485. ISBN 9780313345814.

- ^ "Strand 5: (5ODC Campaigning Organisations Records of the Open Door Council)". twl-calm.library.lse.ac.uk. The Women's Library @ London School of Economics.