Hollywood Subway

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

| Belmont Tunnel / Toluca Substation and Yard | |

|---|---|

Preserved northern rail tunnel portal, 2017 | |

| Coordinates | 34°3′36.56″N 118°15′32.8″W / 34.0601556°N 118.259111°W |

| Designated | February 23, 2005 |

| Reference no. | 790 |

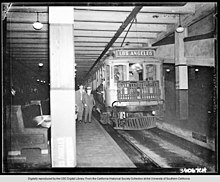

The Hollywood Subway, as it is most commonly known, officially the Belmont Tunnel, was a subway tunnel used by the interurban streetcars (the "Red Cars") of the Pacific Electric Railway. It ran from its northwest entrance in today's Westlake district to the Subway Terminal Building, in the Historic Core, the business and commercial center of Los Angeles from around the 1910s through the 1950s. The Subway Terminal was one of the Pacific Electric Railway’s two main hubs, the other being the Pacific Electric Building at 6th and Main. Numerous lines proceeded from the San Fernando Valley, Glendale, Santa Monica and Hollywood into the tunnel in Westlake and traveled southeast under Crown and Bunker Hill towards the Subway Terminal.

The two-track tunnel, 1.045 miles (1.682 km) long, cut roughly eight miles (13 km) off rail travel through some of the most heavily congested areas in the United States. At its peak, this tunnel hosted 880 Red Cars per day, and served upwards of 20 million passengers a year.

The tunnel's northwest entrance, the shed of what was formerly an electric substation, and the site of the former yard, are just downhill from 299 South Toluca Street, in Westlake. Together they form a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument, the Belmont Tunnel / Toluca Substation and Yard. The monument site is bounded by 2nd Street and the Beverly Boulevard viaduct to the north, Lucas Avenue to the west, Emerald Street uphill to the south, and Toluca Street to the east. Currently, the Belmont Station Apartments stand in front of the tunnel entrance.

History

[edit]Hollywood Subway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

[edit]Early plans for a subway line in Los Angeles included the same alignment as the built tunnel, but continuing further northwest to a point near Bimini Baths and providing connections in Hollywood. A branch would have run to Santa Monica in the west.[1]

1920s – 1950s

[edit]

The monument has a rich history dating back to the early 1920s. Responding to the traffic congestion that clogged the streets of downtown, the California Railroad Commission in 1922 issued Order 9928, which commissioned the Pacific Electric company to dig a subway for new trains to bypass downtown's busy streets and highways.[2] Plans for the proposed "Hollywood Subway" were drafted as early as February 1924, and ground was broken in May of the same year.

After eighteen months of construction and US$1.25 million (equivalent to US$21.7 million in 2023), the Subway officially opened to the public on December 1, 1925.[2] Over about one mile of track, the Subway linked trains heading towards the intersection of Beverly and Glendale Boulevards in Westlake with Los Angeles's newest train station and second electric rail hub, which lay underneath the Subway Terminal Building at the corner of Fourth and Hill Streets, by Pershing Square (due east). Trains through the tunnel were powered by a new substation — Toluca No. 51 — which was built in the yard next to the tunnel's portal. The Subway funneled trains through Westlake and Hollywood to Santa Monica, North Hollywood, and Glendale, cutting seven miles (11 km) or more off similar journeys on rails running along Alameda Street and Exposition Boulevard, which funneled train traffic south and east in Southern California to the other hub, and headquarters, the Pacific Electric Building.

The Subway soon became Los Angeles's most heavily used shortcut. Faster than the automobile and at 6¢ per ride (equivalent to $1.04 in 2023), electric trains carried thousands of travelers each day through it in the 1920s and 1930s. Ridership through the Subway reached its peak during the Second World War: in 1944, 880 trains per day used the tunnel, serving an estimated 65,000 passengers daily, reckoning out to more than 20 million riders a year.[3][4]

After the parent corporation, Southern Pacific Railroad, sold Pacific Electric Railway to a subsidiary of General Motors, trains were replaced with motor buses; Pacific Electric was shut down in 1955. The last electric train to carry passengers — adorned with a banner reading, To Oblivion, left the Belmont Tunnel on the morning of June 19, 1955.[3][5] Shortly thereafter, Southern Pacific lifted the tracks from the Subway, shut up the Subway Terminal Building, disconnected the Toluca Substation, and abandoned the properties.

1960s – present

[edit]

In the 1960s, the city briefly conscripted the Subway for impounded automobiles, and later as a makeshift disaster shelter.[2] In the mid-1960s the middle portion of the tunnel was blocked off by the foundation of one of the skyscrapers on Bunker Hill, creating two separated sections of the original tunnel.[4] Later, in 1974 a piling of the Bonaventure Hotel was driven through the middle portion of the tunnel. Even after the change, the tunnels sections remained a popular location for film and television shoots.[4]

Over the next 35 years, few changes were made to the tunnel, electric substation, or train yard property, and the neglected property became a popular venue for graffiti.[4]

In 2002, the land used for the substation and train yard was sold to West Los Angeles-based Meta Housing Corporation, who agreed to clean and preserve the substation building and the tunnel portal. On the old train yard property Meta built the Belmont Station Apartments, which blocks the tunnel portal. The portal was sealed and painted with a mural of a Red Car by artist Tait Roelofs, which glows in the dark.[6] The substation building and the portal arch were integrated into a park for the building's residents.[4]

In 2007, the Subway Terminal Building was renovated into Metro 417, a luxury apartment building. The developers restored the building's natural stone exterior and removed the drop ceiling from the ornate lobbies. The underground station area remains, but access to what remains of the tunnel is blocked by a wall, and a corner of the old terminal area is separated from the Pershing Square station by a wall.[4]

Film and media location

[edit]

The Hollywood Subway and electric substation are used in a large number of TV shows, films, and other creative genres:

- The electric substation is the Resistance headquarters in the 1980s TV miniseries, V.

- The Belmont Tunnel is the way out of the refugee camp in the 1987 film, The Running Man.

- The substation is a gang clubhouse in the 1988 film, Colors.

- The predator's spacecraft in the 1990 film, Predator 2, was hidden inside the tunnel.

- The substation in the 1992 film, Reservoir Dogs, is the secret place for Freddy Newandyke to prepare himself to go undercover as Mr. Orange.

- The substation is set as an underground nightclub in the 2004 movie, D.E.B.S.

- The cover art for the album, Take Them On, on Your Own, by Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, was photographed inside the tunnel.

- The substation appears in the video for “Under the Bridge.”

- The video for By the Way, by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, is set inside the tunnel.

- The substation is seen briefly in the music video for “Get U Down Pt. 2,” by Warren G.

- The tunnel and substation are featured in the 2005 skateboarding video game Tony Hawk's American Wasteland, in which the player takes the tunnel to ride from Downtown LA to East LA.

- The 2011 neo-noir-detective video game L.A. Noire, set in 1947, recreates the tunnel and substation in full use.

- The video for "Maria Maria" by Carlos Santana is set in front of the substation.

- The music video for "One Step Closer" by Linkin Park is mostly set within the tunnel.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wood, J. Henry (1907). Security Map And Street Railway Guide of the City of Los Angeles and Vicinity with Map of Beaches and nearby Points of Interest (Map). Los Angeles, California: Security Savings Bank. Retrieved September 4, 2021 – via David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

- ^ a b c "Pacific Electric Hollywood Subway". Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California.

- ^ a b "Pacific Electric Subway Terminal". Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California.

- ^ a b c d e f Howser, Huell (November 17, 2008). "Subway Terminal Update". Visiting...With Huell Howser. Season 16. Episode 17. KCET.

- ^ "L.A. Subway Closes After Special Trolley Car Trip" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. June 20, 1955. p. 8. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Harvey, Steve (February 8, 2009). "The colorful saga of Los Angeles' first subway tunnel". Los Angeles Times.

External links

[edit]- Wikimapia, Pacific Electric Belmont Tunnel Portal, with historic photographs

- Documentary on the Belmont Tunnel focusing on its history as a railroad depot, as a graffiti yard, and as a field where community residents played the Tarasca game

- Los Angeles’ Forgotten Hollywood Subway", Jay Moon, INSH, September 2016

- "Hollywood Subway", Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California

- "The 1925 Hollywood Subway", Lindsay William-Ross, LAist, July 2008 Archived August 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Hollywood Subway: Against the Horizontal City", Aaron Gilbreath, The Paris Review, January 2013

KSF

KSF