Horst (geology)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

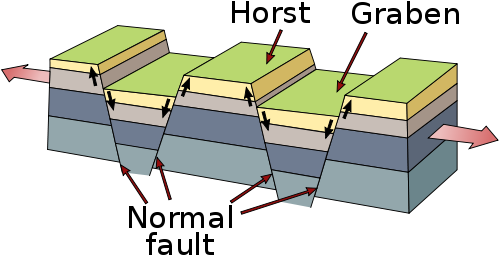

In physical geography and geology, a horst is a raised fault block bounded by normal faults.[1] Horsts are typically found together with grabens. While a horst is lifted or remains stationary, the grabens on either side subside.[2] This is often caused by extensional forces pulling apart the crust. Horsts may represent features such as plateaus, mountains, or ridges on either side of a valley.[3] Horsts can range in size from small fault blocks up to large regions of stable continent that have not been folded or warped by tectonic forces.[2]

The word Horst, apart from being a common name, in general German refers to an "eagle's nest". The actual older meaning is "(wooded) hill top", "mass" or "heap", basically anything elevated. The term, as used in "Bergmannssprache", the special "language" of miners, was first adopted in the geological sense in 1883 by Eduard Suess in The Face of the Earth.[4][5][note 1]

Geomorphology

[edit]Horsts may have either symmetrical or asymmetrical cross-sections. If the normal faults to either side have similar geometry and are moving at the same rate, the horst is likely to be symmetrical and roughly flat on top. If the faults on either side have different rates of vertical motion, the top of the horst will most likely be inclined and the entire profile will be asymmetrical. Erosion also plays a significant role in how symmetrical a horst appears in cross-section.[citation needed]

Horsts and hydrocarbon exploration

[edit]Horsts can form structural petroleum traps.[6] In many rift basins around the world, the vast majority of discovered hydrocarbons are found in conventional traps associated with horsts.[citation needed] For example, much of the petroleum found in the Sirte Basin, Libya (of the order of tens of billions of barrels of reserves) are found on large horst blocks[7] such as the Zelten Platform and the Dahra Platform and on smaller horsts such as the Gialo High.[8]

Examples

[edit]The Vosges Mountains in France and Black Forest in Germany are examples of horsts, as are the Table, Jura, the Dole mountains and the Rila – Rhodope Massif including the well defined horsts of Belasitsa (linear horst), Rila mountain (vaulted domed shaped horst) and Pirin mountain – a horst forming a massive anticline situated between the complex graben valleys of Struma and that of Mesta.[9][10][11]

Larger areas where the continent remains stable with horizontal table-land stratification can be considered horsts, such as the Russian Plain, Arabia, India and Central South Africa. This is in distinction to folded regions such as some mountain chains of Eurasia.[2]

The Midcontinent Rift System in North America is marked by a series of horsts extending from Lake Superior to Kansas.[12]

The Rwenzori Mountains in the East African Rift are an upthrown fault block, and are the highest non-volcanic, non-orogenic mountains in the world.[13][14]

The Vosges Mountains in France were formed by isostatic uplift in response to the opening of the Rhine Graben, a major extensional basin.[15]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Originally published in 1883 in German as "Das Antlitz der Erde", translated and published in English in 1904

References

[edit]- ^ Fossen H. (2010-07-15). Structural Geology. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9781139488617.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Horst". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 740.

- ^ "Horst and Graben". National Park Service. 2020-04-22.

- ^ "horst". Etymonline.

- ^ Suess, Edward (1904). The Face of the Earth. Translated by Sollas, Hertha B C. Clarendon Press.

- ^ "Hydrocarbon Traps". Geology In. 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ^ Parsons, M.G.; Zagaar, A.M.; Curry, J.J. (1980). "Hydrocarbon occurrences in the Sirte Basin, Libya". Facts and Principles of World Petroleum Occurrence Memoirs. 6: 723–732. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Selley, R. C. (1 January 1997). "Chapter 3 The sirte basin of libya". Sedimentary Basins of the World. 3: 27–37. doi:10.1016/S1874-5997(97)80006-8. ISBN 9780444825711.

- ^ Мичев (Michev), Николай (Nikolay); Михайлов (Mihaylov), Цветко (Tsvetko); Вапцаров (Vaptsarov), Иван (Ivan); Кираджиев (Kiradzhiev), Светлин (Svetlin) (1980). Географски речник на България [Geographic Dictionary of Bulgaria] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Наука и култура (Nauka i kultura). p. 368.

- ^ Димитрова (Dimitrova), Людмила (Lyudmila) (2004). Национален парк "Пирин". План за управление [Pirin National Park. Management Plan] (in Bulgarian). и колектив. Sofia: Ministry of Environment and Water, Bulgarian Foundation "Biodiversity". p. 53.

- ^ Дончев (Donchev), Дончо (Doncho); Каракашев (Karakashev), Христо (Hristo) (2004). Теми по физическа и социално-икономическа география на България [Topics on Physical and Social-Economic Geography of Bulgaria] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Ciela. pp. 128–129. ISBN 954-649-717-7.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (1989). "Clastic Rocks Associated with the Midcontinent Rift System in Iowa" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1989–I: 11. Retrieved Sep 3, 2018.

- ^ Ring, Uwe (2008-08-27). "Extreme uplift of the Rwenzori Mountains in the East African Rift, Uganda: Structural framework and possible role of glaciations". Tectonics. 27 (4). Bibcode:2008Tecto..27.4018R. doi:10.1029/2007tc002176. ISSN 0278-7407. S2CID 129376195.

- ^ "The Mountains of the Moon". Volcano Cafe. 20 February 2021.

- ^ "horst and graben". Encyclopædia Britannica.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of horst at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of horst at Wiktionary

KSF

KSF