-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, front view

-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint, back view

-

The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula.

-

Head of humerus

-

The supinator.

Humerus

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

| Humerus | |

|---|---|

Position of humerus (shown in red) from an anterior viewpoint | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | humerus |

| MeSH | D006811 |

| TA98 | A02.4.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1180 |

| FMA | 13303 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

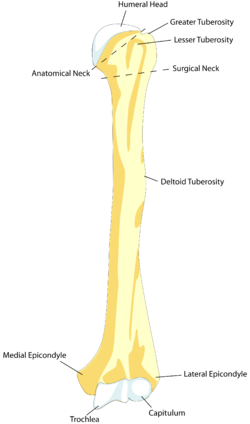

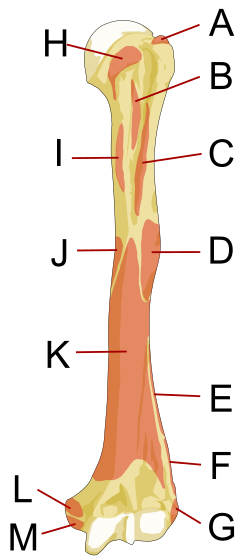

The humerus (/ˈhjuːmərəs/; pl.: humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a rounded head, a narrow neck, and two short processes (tubercles, sometimes called tuberosities). The shaft is cylindrical in its upper portion, and more prismatic below. The lower extremity consists of 2 epicondyles, 2 processes (trochlea and capitulum), and 3 fossae (radial fossa, coronoid fossa, and olecranon fossa). As well as its true anatomical neck, the constriction below the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus is referred to as its surgical neck due to its tendency to fracture, thus often becoming the focus of surgeons.

Etymology

[edit]The word "humerus" is derived from Late Latin humerus, from Latin umerus, meaning upper arm, shoulder, and is linguistically related to Gothic ams (shoulder) and Greek ōmos.[1]

Structure

[edit]Upper extremity

[edit]The upper or proximal extremity of the humerus consists of the bone's large rounded head joined to the body by a constricted portion called the neck, and two eminences, the greater and lesser tubercles.

Head

[edit]

The head (caput humeri) is nearly hemispherical in form. It is directed upward, medialward, and a little backward, and articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula to form the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint). The circumference of its articular surface is slightly constricted and is termed the anatomical neck, in contradistinction to a constriction below the tubercles called the surgical neck which is frequently the seat of fracture. Fracture of the anatomical neck rarely occurs.[2] The diameter of the humeral head is generally larger in men than in women.

Anatomical neck

[edit]The anatomical neck (collum anatomicum) is obliquely directed, forming an obtuse angle with the body. It is most prominent in the lower half of its circumference, while in the upper half, it is represented by a narrow groove separating the head from the tubercles. The line separating the head from the rest of the upper end is called the anatomical neck. It affords attachment to the articular capsule of the shoulder-joint, and is perforated by numerous vascular foramens. Fracture of the anatomical neck rarely occurs.[2]

The anatomical neck of the humerus is an indentation distal to the head of the humerus on which the articular capsule attaches.

Surgical neck

[edit]The surgical neck is a narrow area distal to the tubercles that is a common site of fracture. It makes contact with the axillary nerve and the posterior humeral circumflex artery.

Greater tubercle

[edit]The greater tubercle (tuberculum majus; greater tuberosity) is a large, posteriorly placed projection that is placed laterally. The greater tubercle is where supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles are attached. The crest of the greater tubercle forms the lateral lip of the bicipital groove and is the site for insertion of pectoralis major.

The greater tubercle is just lateral to the anatomical neck. Its upper surface is rounded and marked by three flat impressions: the highest of these gives insertion to the supraspinatus muscle; the middle to the infraspinatus muscle; the lowest one, and the body of the bone for about 2.5 cm. below it, to the teres minor muscle. The lateral surface of the greater tubercle is convex, rough, and continuous with the lateral surface of the body.[2]

Lesser tubercle

[edit]The lesser tubercle (tuberculum minus; lesser tuberosity) is smaller, anterolaterally placed to the head of the humerus. The lesser tubercle provides insertion to subscapularis muscle. Both these tubercles are found in the proximal part of the shaft. The crest of the lesser tubercle forms the medial lip of the bicipital groove and is the site for insertion of teres major and latissimus dorsi muscles.

The lesser tuberosity, is more prominent than the greater: it is situated in front, and is directed medialward and forward. Above and in front it presents an impression for the insertion of the tendon of the subscapularis muscle.[2]

Bicipital groove

[edit]The tubercles are separated from each other by a deep groove, the bicipital groove (intertubercular groove; bicipital sulcus), which lodges the long tendon of the biceps brachii muscle and transmits a branch of the anterior humeral circumflex artery to the shoulder-joint. It runs obliquely downward, and ends near the junction of the upper with the middle third of the bone. In the fresh state its upper part is covered with a thin layer of cartilage, lined by a prolongation of the synovial membrane of the shoulder-joint; its lower portion gives insertion to the tendon of the latissimus dorsi muscle. It is deep and narrow above, and becomes shallow and a little broader as it descends. Its lips are called, respectively, the crests of the greater and lesser tubercles (bicipital ridges), and form the upper parts of the anterior and medial borders of the body of the bone.[2]

Shaft

[edit]| Body of humerus | |

|---|---|

Left humerus. Anterior view. | |

Left humerus. Posterior view. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | corpus humeri |

| MeSH | D006811 |

| TA98 | A02.4.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1180 |

| FMA | 13303 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The body or shaft of the humerus is triangular to cylindrical in cut section and is compressed anteroposteriorly. It has 3 surfaces, namely:

- Anterolateral surface: the area between the lateral border of the humerus to the line drawn as a continuation of the crest of the greater tubercle. The antero-lateral surface is directed lateralward above, where it is smooth, rounded, and covered by the deltoid muscle; forward and lateralward below, where it is slightly concave from above downward, and gives origin to part of the brachialis. About the middle of this surface is a rough, rectangular elevation, the deltoid tuberosity for the insertion of the deltoid muscle; below this is the radial sulcus, directed obliquely from behind, forward, and downward, and transmitting the radial nerve and profunda artery.

- Anteromedial surface: the area between the medial border of the humerus to the line drawn as a continuation of the crest of the greater tubercle. The antero-medial surface, less extensive than the antero-lateral, is directed medialward above, forward and medialward below; its upper part is narrow, and forms the floor of the intertubercular groove which gives insertion to the tendon of the latissimus dorsi muscle; its middle part is slightly rough for the attachment of some of the fibers of the tendon of insertion of the coracobrachialis muscle; its lower part is smooth, concave from above downward, and gives origin to the brachialis muscle.

- Posterior surface: the area between the medial and lateral borders. The posterior surface appears somewhat twisted, so that its upper part is directed a little medialward, its lower part backward and a little lateralward. Nearly the whole of this surface is covered by the lateral and medial heads of the Triceps brachii, the former arising above, the latter below the radial sulcus.

Its three borders are:

- Anterior: the anterior border runs from the front of the greater tubercle above to the coronoid fossa below, separating the antero-medial from the antero-lateral surface. Its upper part is a prominent ridge, the crest of the greater tubercle; it serves for the insertion of the tendon of the pectoralis major muscle. About its center it forms the anterior boundary of the deltoid tuberosity, on which the deltoid muscle attaches; below, it is smooth and rounded, affording attachment to the brachialis muscle.

- Lateral: the lateral border runs from the back part of the greater tubercle to the lateral epicondyle, and separates the anterolateral from the posterior surface. Its upper half is rounded and indistinctly marked, serving for the attachment of the lower part of the insertion of the teres minor muscle, and below this giving origin to the lateral head of the triceps brachii muscle; its center is traversed by a broad but shallow oblique depression, the spiral groove (musculospiral groove). The radial nerve runs in the spiral groove. Its lower part forms a prominent, rough margin, a little curved from backward, forward the lateral supracondylar ridge, which presents an anterior lip for the origin of the brachioradialis muscle two-thirds above, and extensor carpi radialis longus muscle one-third below, a posterior lip for the triceps brachii muscle, and an intermediate ridge for the attachment of the lateral intermuscular septum.

- Medial: the medial border extends from the lesser tubercle to the medial epicondyle. Its upper third consists of a prominent ridge, the crest of the lesser tubercle, which gives insertion to the tendon of the teres major muscle. About its center is a slight impression for the insertion of the coracobrachialis muscle, and just below this is the entrance of the nutrient canal, directed downward; sometimes there is a second nutrient canal at the commencement of the radial sulcus. The inferior third of this border is raised into a slight ridge, the medial supracondylar ridge, which became very prominent below; it presents an anterior lip for the origins of the brachialis muscle and the pronator teres muscle, a posterior lip for the medial head of the triceps brachii muscle, and an intermediate ridge for the attachment of the medial intermuscular septum.

The deltoid tuberosity is a roughened surface on the lateral surface of the shaft of the humerus and acts as the site of insertion of deltoideus muscle. The posterorsuperior part of the shaft has a crest, beginning just below the surgical neck of the humerus and extends till the superior tip of the deltoid tuberosity. This is where the lateral head of triceps brachii is attached.

The radial sulcus, also known as the spiral groove, is found on the posterior surface of the shaft and is a shallow oblique groove through which the radial nerve passes along with deep vessels. This is located posteroinferior to the deltoid tuberosity. The inferior boundary of the spiral groove is continuous distally with the lateral border of the shaft.

The nutrient foramen of the humerus is located in the anteromedial surface of the humerus. The nutrient arteries enter the humerus through this foramen.

Distal humerus

[edit]| Lower extremity of humerus | |

|---|---|

Left humerus. Anterior view. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | extremitas distalis humeri |

| MeSH | D006811 |

| TA98 | A02.4.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1180 |

| FMA | 13303 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The distal or lower extremity of the humerus is flattened from before backward, and curved slightly forward; it ends below in a broad, articular surface, which is divided into two parts by a slight ridge. Projecting on either side are the lateral and medial epicondyles.

Articular surface

[edit]The articular surface extends a little lower than the epicondyles, and is curved slightly forward; its medial extremity occupies a lower level than the lateral. The lateral portion of this surface consists of a smooth, rounded eminence, named the capitulum of the humerus; it articulates with the cup-shaped depression on the head of the radius, and is limited to the front and lower part of the bone.

Fossae

[edit]Above the front part of the trochlea is a small depression, the coronoid fossa, which receives the coronoid process of the ulna during flexion of the forearm.

Above the back part of the trochlea is a deep triangular depression, the olecranon fossa, in which the summit of the olecranon is received in extension of the forearm.

The coronoid fossa is the medial hollow part on the anterior surface of the distal humerus. The coronoid fossa is smaller than the olecranon fossa and receives the coronoid process of the ulna during maximum flexion of the elbow.

Above the front part of the capitulum is a slight depression, the radial fossa, which receives the anterior border of the head of the radius, when the forearm is flexed.

These fossæ are separated from one another by a thin, transparent lamina of bone, which is sometimes perforated by a supratrochlear foramen; they are lined in the fresh state by the synovial membrane of the elbow-joint, and their margins afford attachment to the anterior and posterior ligaments of this articulation.

The capitulum is a rounded eminence forming the lateral part of the distal humerus. The head of the radius articulates with the capitulum.

The trochlea is spool-shaped medial portion of the distal humerus and articulates with the ulna.

Epicondyles

[edit]The epicondyles are continuous above with the supracondylar ridges.

- The lateral epicondyle is a small, tuberculated eminence, curved a little forward, and giving attachment to the radial collateral ligament of the elbow-joint, and to a tendon common to the origin of the supinator and some of the extensor muscles.

- The medial epicondyle, larger and more prominent than the lateral, is directed a little backward; it gives attachment to the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow-joint, to the pronator teres, and to a common tendon of origin of some of the flexor muscles of the forearm; the ulnar nerve runs in a groove on the back of this epicondyle.

The medial supracondylar crest forms the sharp medial border of the distal humerus continuing superiorly from the medial epicondyle. The lateral supracondylar crest forms the sharp lateral border of the distal humerus continuing superiorly from the lateral epicondyle.[3]

Borders

[edit]The medial portion of the articular surface is named the trochlea, and presents a deep depression between two well-marked borders; it is convex from before backward, concave from side to side, and occupies the anterior, lower, and posterior parts of the extremity.

- The lateral border separates it from the groove which articulates with the margin of the head of the radius.

- The medial border is thicker, of greater length, and consequently more prominent, than the lateral.

The grooved portion of the articular surface fits accurately within the semilunar notch of the ulna; it is broader and deeper on the posterior than on the anterior aspect of the bone, and is inclined obliquely downward and forward toward the medial side.

Articulations

[edit]At the shoulder, the head of the humerus articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula. More distally, at the elbow, the capitulum of the humerus articulates with the head of the radius, and the trochlea of the humerus articulates with the trochlear notch of the ulna.

Nerves

[edit]The axillary nerve is located at the proximal end, against the shoulder girdle. Dislocation of the humerus's glenohumeral joint has the potential to injure the axillary nerve or the axillary artery. Signs and symptoms of this dislocation include a loss of the normal shoulder contour and a palpable depression under the acromion.

The radial nerve follows the humerus closely. At the midshaft of the humerus, the radial nerve travels from the posterior to the anterior aspect of the bone in the spiral groove. A fracture of the humerus in this region can result in radial nerve injury.

The ulnar nerve lies at the distal end of the humerus near the elbow. When struck, it can cause a distinct tingling sensation, and sometimes a significant amount of pain. It is sometimes popularly referred to as 'the funny bone', possibly due to this sensation (a "funny" feeling), as well as the fact that the bone's name is a homophone of 'humorous'.[4] It lies posterior to the medial epicondyle, and is easily damaged in elbow injuries.[citation needed]

-

Horizontal section at the middle of upper arm.

-

Horizontal section of upper arm.

-

Humerus

Function

[edit]Muscular attachment

[edit]The deltoid originates on the lateral third of the clavicle, acromion and the crest of the spine of the scapula. It is inserted on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus and has several actions including abduction, extension, and circumduction of the shoulder. The supraspinatus also originates on the spine of the scapula. It inserts on the greater tubercle of the humerus, and assists in abduction of the shoulder.

The pectoralis major, teres major, and latissimus dorsi insert at the intertubercular groove of the humerus. They work to adduct and medially, or internally, rotate the humerus.

The infraspinatus and teres minor insert on the greater tubercle, and work to laterally, or externally, rotate the humerus. In contrast, the subscapularis muscle inserts onto the lesser tubercle and works to medially, or internally, rotate the humerus.

The biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis (which attaches distally) act to flex the elbow. (The biceps do not attach to the humerus.) The triceps brachii and anconeus extend the elbow, and attach to the posterior side of the humerus.

The four muscles of supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis form a musculo-ligamentous girdle called the rotator cuff. This cuff stabilizes the very mobile but inherently unstable glenohumeral joint. The other muscles are used as counterbalances for the actions of lifting/pulling and pressing/pushing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other animals

[edit]Primitive fossils of amphibians had little, if any, shaft connecting the upper and lower extremities, making their limbs very short. In most living tetrapods, however, the humerus has a similar form to that of humans. In many reptiles and some mammals (where it is the primitive state), the lower extremity includes a large opening called the entepicondylar foramen to allow the passage of nerves and blood vessels.[5]

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of humerus (shown in red). Animation.

-

Left humerus. Animation.

-

3D image

-

Human arm bones diagram.

-

Humerus - inferior epiphysis. Anterior view.

-

Trochlea. Posterior view.

-

Humerus - inferior epiphysis. Posterior view.

-

Humerus - superior epiphysis. Anterior view.

-

Humerus - superior epiphysis. Posterior view.

-

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Elbow joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

The left shoulder and acromioclavicular joints, and the proper ligaments of the scapula

-

Left humerus. Anterior view.

-

Left humerus. Posterior view.

-

Left humerus. Anteriolateral view.

-

Left humerus. Medial view.

-

Fracture of the proximal humerus

-

Left elbow-joint, showing anterior and ulnar collateral ligaments.

-

Capsule of elbow-joint (distended). Posterior aspect.

-

Humerus anatomy

Ossification

[edit]During embryonic development, the humerus is one of the first structures to ossify, beginning with the first ossification center in the shaft of the bone. Ossification of the humerus occurs predictably in the embryo and fetus, and is therefore used as a fetal biometric measurement when determining gestational age of a fetus. At birth, the neonatal humerus is only ossified in the shaft. The epiphyses are cartilaginous at birth.[6] The medial humeral head develops an ossification center around 4 months of age and the greater tuberosity around 10 months of age. These ossification centers begin to fuse at 3 years of age. The process of ossification is complete by 13 years of age, though the epiphyseal plate (growth plate) persists until skeletal maturity, usually around 17 years of age.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Humerus". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Gray's Anatomy, see infobox

- ^ "Humerus Anatomy at DocJana.com". docjana.com. 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Funny Bone". Word Detective.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Wiśniewski, Marcin; Baumgart, Mariusz; Grzonkowska, Magdalena; Małkowski, Bogdan; Wilińska-Jankowska, Arnika; Siedlecki, Zygmunt; Szpinda, Michał (October 2017). "Ossification center of the humeral shaft in the human fetus: a CT, digital, and statistical study". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 39 (10): 1107–1116. doi:10.1007/s00276-017-1849-4. ISSN 1279-8517. PMC 5610672. PMID 28357556. Archived from the original on Dec 19, 2024 – via PubMed Central.

- ^ Kwong, Steven; Kothary, Shefali; Poncinelli, Leonardo Lobo (February 2014). "Skeletal Development of the Proximal Humerus in the Pediatric Population: MRI Features". American Journal of Roentgenology. 202 (2): 418–425. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10711. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 24450686.

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 209 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 209 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

[edit]- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Humerus[permanent dead link] - BlueLink Anatomy, University of Michigan Medical School

KSF

KSF