Hussites

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Hussites (Czech: Husité or Kališníci, "Chalice People"; Latin: Hussitae) were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement influenced by both the Byzantine Rite and John Wycliffe that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus (fl. 1401–1415), a part of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Czech lands had originally been Christianized by Byzantine Greek missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, who introduced the Byzantine Rite in the Old Church Slavonic liturgical language and the Byzantine tradition of Communion in both kinds administered by the holy spoon. Over the centuries that followed, however, the Roman Rite in Ecclesiastical Latin, which is less easily understood than Slavonic by native speakers of Old Czech, was imposed upon the Czech people despite considerable public resistance, by German-speaking bishops, beginning with Wiching, from the Holy Roman Empire. (See also Sázava Monastery).[1] As a cultural memory of both communion in both kinds and the Divine Liturgy in a language closer to the vernacular is believed to have survived well into the Renaissance, the ideas of Jan Hus and others like him swiftly gained a wide public following. After the trial and execution of Hus at the Council of Constance,[2] a series of crusades, civil wars, victories and compromises between various factions with different theological agendas broke out. At the end of the Hussite Wars (1420–1434), the now Catholic-supported Utraquist side came out victorious from protracted conflict against Jan Žižka and the Taborites, who embraced the more radical theological teachings of John Wycliffe and the Lollards, and became the dominant Hussite group in Bohemia.

Catholics and Utraquists were given legal equality in Bohemia after the religious peace of Kutná Hora in 1485. Bohemia and Moravia, or what is now the territory of the Czech Republic, remained majority Hussite for two centuries. Roman Catholicism was only reimposed by the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II following the 1620 Battle of White Mountain and during the Thirty Years' War.

The Hussite tradition continues in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren and, since the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, by the re-founded Czechoslovak Hussite Church.[3] The revived legacy of Saints Cyril and Methodius also continues in both the Orthodox Church in the Czech Lands and the Apostolic Exarchate of the Greek Catholic Church in the Czech Republic.

History

[edit]The Hussite movement began in the Kingdom of Bohemia and quickly spread throughout the remaining Lands of the Bohemian Crown, including Moravia and Silesia. It also made inroads into the northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), but was rejected and gained infamy for the plundering behaviour of the Hussite soldiers.[4][5][6][7] There were also very small temporary communities in Poland-Lithuania and Transylvania which moved to Bohemia after being confronted with religious intolerance. It was a regional movement that failed to expand farther. Hussites emerged as a majority Utraquist movement with a significant Taborite faction, and smaller regional ones that included Adamites, Orebites and Orphans.

Major Hussite theologians included Petr Chelčický and Jerome of Prague. A number of Czech national heroes were Hussite, including Jan Žižka, who led a fierce resistance to five consecutive crusades proclaimed on Hussite Bohemia by the Papacy. Hussites were one of the most important forerunners of the Protestant Reformation. This predominantly religious movement was propelled by social issues and strengthened Czech national awareness.

Hus's death

[edit]

The Council of Constance lured Jan Hus in with a letter of indemnity, then tried him for heresy and put him to death at the stake on 6 July 1415.[2]

The arrest of Hus in 1414 caused considerable resentment in Czech lands. The authorities of both countries appealed urgently and repeatedly to King Sigismund to release Jan Hus.

When news of his death at the Council of Constance arrived, disturbances broke out, directed primarily against the clergy and especially against the monks. Even the Archbishop narrowly escaped from the effects of this popular anger. The treatment of Hus was felt to be a disgrace inflicted upon the whole country and his death was seen as a criminal act. King Wenceslaus IV., prompted by his grudge against Sigismund, at first gave free vent to his indignation at the course of events in Constance. His wife openly favoured the friends of Hus. Avowed Hussites stood at the head of the government.

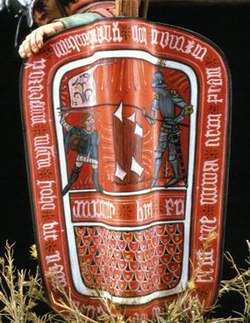

A league was formed by certain lords,[who?] who pledged themselves to protect the free preaching of the Gospel upon all their possessions and estates and to obey the power of the Bishops only where their orders accorded with the injunctions of the Bible. The university would arbitrate any disputed points. The entire Hussite nobility joined the league. Other than verbal protest of the council's treatment of Hus, there was little evidence of any actions taken by the nobility until 1417. At that point several of the lesser nobility and some barons, signatories of the 1415 protest letter, removed Catholic priests from their parishes, replacing them with priests willing to give communion in both wine and bread. The chalice of wine became the central identifying symbol of the Hussite movement.[8] If the king had joined, its resolutions would have received the sanction of the law; but he refused, and approached the newly formed Roman Catholic League of lords, whose members pledged themselves to support the king, the Catholic Church, and the council. The prospect of a civil war began to emerge.

Prior to becoming pope, Martin V, then known as Cardinal Otto of Colonna had attacked Hus with relentless severity. He energetically resumed the battle against Hus's teaching after the enactments of the Council of Constance. He wished to eradicate completely the doctrine of Hus, for which purpose the co-operation of King Wenceslaus had to be obtained.[citation needed] In 1418, Sigismund succeeded in winning his brother over to the standpoint of the council by pointing out the inevitability of a religious war if the heretics in Bohemia found further protection.[citation needed] Hussite statesmen and army leaders had to leave the country and Roman Catholic priests were reinstated. These measures caused a general commotion which hastened the death of King Wenceslaus by a paralytic stroke in 1419.[citation needed] His heir was Sigismund.

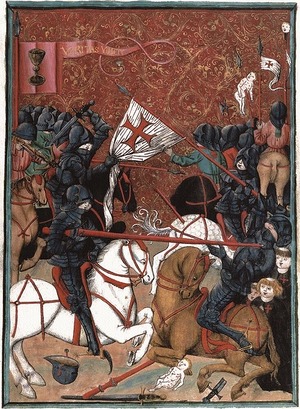

Hussite Wars (1419–1434)

[edit]

The news of the death of King Wenceslaus in 1419 produced a great commotion among the people of Prague. A revolution swept over the country: churches and monasteries were destroyed, and church property was seized by the Hussite nobility. It was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (Čeněk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. Sigismund could get possession of "his" kingdom only by force of arms. Pope Martin V called upon Catholics of the West to take up arms against the Hussites, declaring a crusade, and twelve years of warfare followed.

The Hussites initially campaigned defensively, but after 1427 they assumed the offensive. Apart from their religious aims, they fought for the national interests of the Czechs. The moderate and radical parties were united, and they not only repelled the attacks of the army of crusaders but crossed the borders into neighboring countries. On March 23, 1430, Joan of Arc dictated a letter[9] that threatened to lead a crusading army against the Hussites unless they returned to the Catholic faith, but her capture by English and Burgundian troops two months later would keep her from carrying out this threat.

Council of Basel and Compacta of Prague

[edit]Eventually, the opponents of the Hussites found themselves forced to consider an amicable settlement. The Hussites were sent an invitation to attend the ecumenical Council of Basel on October 15, 1431.[10] The discussions began on 10 January 1432, focusing chiefly on the four articles of Prague. No agreement emerged. After repeated negotiations between the Basel Council and Bohemia, a Bohemian–Moravian state assembly in Prague accepted the "Compactata" of Prague on 30 November 1433. The agreement granted communion in both kinds to all who desired it, but with the understanding that Christ was entirely present in each kind, though on the condition that the rest of the Hussite reforms would no longer be emphasised.[10] Free preaching was granted conditionally: the Church hierarchy had to approve and place priests, and the power of the bishop must be considered. The article which prohibited the secular power of the clergy was almost reversed.

The Taborites refused to conform. The Calixtines united with the Roman Catholics and destroyed the Taborites at the Battle of Lipany on 30 May 1434.[11] From that time, the Taborites lost their importance, though the Hussite movement would continue in Poland for another five years, until the Royalist forces of Poland defeated the Polish Hussites at the Battle of Grotniki. The state assembly of Jihlava in 1436 confirmed the "Compactata" and gave them the sanction of law. This accomplished the reconciliation of Bohemia with Rome and the Western Church, and at last Sigismund obtained possession of the Bohemian crown.[11] His reactionary measures caused a ferment in the whole country, but he died in 1437. The state assembly in Prague rejected Wyclif's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, which was obnoxious to the Utraquists, as heresy in 1444. Most of the Taborites now went over to the party of the Utraquists; the rest joined the "Brothers of the Law of Christ" (Latin: "Unitas Fratrum") (see history of the Moravian Church).

Hussite Bohemia, Luther and the Reformation (1434–1618)

[edit]

In 1462, Pope Pius II declared the "Compacta" null and void, prohibited communion in both kinds, and acknowledged King George of Podebrady as king on condition that he would promise an unconditional harmony with the Roman Church. This he refused, leading to the Bohemian–Hungarian War (1468–1478). His successor, King Vladislaus II, favored the Roman Catholics and proceeded against some zealous clergymen of the Calixtines. The troubles of the Utraquists increased from year to year. In 1485, at the Diet of Kutná Hora, an agreement was made between the Roman Catholics and Utraquists that lasted for thirty-one years. It was only later, at the Diet of 1512, that the equal rights of both religions were permanently established. The appearance of Martin Luther was hailed by the Utraquist clergy, and Luther himself was astonished to find so many points of agreement between the doctrines of Hus and his own. But not all Utraquists approved of the German Reformation; a schism arose among them, and many returned to the Roman doctrine, while other elements had organised the "Unitas Fratrum" already in 1457.

Bohemian Revolt and harsh persecution under the Habsburgs (1618–1918)

[edit]Under Emperor Maximilian II, the Bohemian state assembly established the Confessio Bohemica, upon which Lutherans, Reformed, and Bohemian Brethren agreed. From that time forward Hussitism began to die out. After the Battle of White Mountain on 8 November 1620 the Roman Catholic Faith was re-established with vigour, which fundamentally changed the religious conditions of the Czech lands.

Leaders and members of Unitas Fratrum were forced to choose to either leave the many and varied southeastern principalities of what was the Holy Roman Empire (mainly Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia and parts of Germany and its many states), or to practice their beliefs secretly. As a result, members were forced underground and dispersed across northwestern Europe. The largest remaining communities of the Brethren were located in Lissa (Leszno) in Poland, which had historically strong ties with the Czechs, and in small, isolated groups in Moravia. Some, among them Jan Amos Comenius, fled to western Europe, mainly the Low Countries. A settlement of Hussites in Herrnhut, Saxony, now Germany, in 1722 caused the emergence of the Moravian Church.

Post-Habsburg era and modern times (1918–present)

[edit]

In 1918, as a result of World War I, the Czech lands regained independence from Austria-Hungary controlled by the Habsburg monarchy as Czechoslovakia (due to Masaryk and Czechoslovak legions with Hussite tradition, in the name of the troops).[12]

Today, the Hussite tradition is represented in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren, and Czechoslovak Hussite Church.[3][13]

Factions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

Hussitism organised itself during the years 1415–1419. Hussites were not a unitary movement, but a diverse one with multiple factions that held different views and opposed each other in the Hussite Wars. From the beginning, there formed two parties, with a smaller number of people withdrawing from both parties around the pacifist Petr Chelčický, whose teachings would form the foundation of the Unitas Fratrum. Hussites can be divided into:

Moderates

[edit]The more conservative Hussites (the moderate party, or Utraquists), who followed Hus more closely, sought to conduct reform while leaving the whole hierarchical and liturgical order of the Church untouched.[14]

Their programme is contained in the Four Articles of Prague, which were written by Jacob of Mies and agreed upon in July 1420, promulgated in the Latin, Czech, and German languages. They can be summarised as follows: [15]

- Free preaching of the Word of God throughout the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Margravate of Moravia.

- Celebration of the communion under both kinds (bread and wine to priests and laity alike)

- The removal of secular power from the clergy.

- Secular punishment for mortal sins among clergy and laity alike.

The views of the moderate Hussites were widely represented at the university and among the citizens of Prague; they were therefore called the Prague Party, but also Calixtines (Latin calix chalice) or Utraquists (Latin utraque both), because they emphasized the second article of Prague, and the chalice became their emblem.

Radicals

[edit]The more radical parties, the Taborites, Orebites and Orphans, identified itself more boldly with the doctrines of John Wycliffe, sharing his passionate hatred of the monastic clergy, and his desire to return the Church to its supposed condition during the time of the apostles. This required the removal of the existing hierarchy and the secularisation of ecclesiastical possessions. Above all they clung to Wycliffe's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, denying transubstantiation,[16] and this is the principal point by which they are distinguished from the moderate party, the Utraquists.

The radicals preached the "sufficientia legis Christi"—the divine law (i.e. the Bible) is the sole rule and canon for human society, not only in the church, but also in political and civil matters. They rejected therefore, as early as 1416, everything that they believed had no basis in the Bible, such as the veneration of saints and images, fasts, superfluous holidays, the oath, intercession for the dead, auricular Confession, indulgences, the sacraments of Confirmation and the Anointing of the Sick, and chose their own priests.

The radicals had their gathering-places all around the country. Their first armed assault fell on the small town of Ústí, on the river Lužnice, south of Prague (today's Sezimovo Ústí). However, as the place did not prove to be defensible, they settled in the remains of an older town upon a hill not far away and founded a new town, which they named Tábor (a play on words, as "Tábor" not only meant "camp" or "encampment" in Czech,[17] but is also the traditional name of the mountain on which Jesus was expected to return; see Mark 13); hence they were called Táborité (Taborites). They comprised the essential force of the radical Hussites.

Their aim was to destroy the enemies of the law of God, and to defend his kingdom (which had been expected to come in a short time) by the sword. Their end-of-world visions did not come true. In order to preserve their settlement and spread their ideology, they waged bloody wars; in the beginning they observed a strict regime, inflicting the severest punishment equally for murder, as for less severe faults as adultery, perjury, and usury, and also tried to apply rigid Biblical standards to the social order of the time. The Taborites usually had the support of the Orebites (later called Orphans), an eastern Bohemian sect of Hussitism based in Hradec Králové.

See also

[edit]- Arnoldists

- Hussite Bible

- Lollards

- Pavel Kravař

- Restorationism

- Taborites

- Jistebnice hymn book

- Waldensians

- War wagon

References

[edit]- ^ Dvornik, F. (1964). "The Significance of the Missions of Cyril and Methodius". Slavic Review. 23 (2): 195–211. doi:10.2307/2492930. JSTOR 2492930. S2CID 163378481.

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "Constance, Council of"

- ^ a b Nĕmec, Ludvík "The Czechoslovak heresy and schism: the emergence of a national Czechoslovak church," American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1975, ISBN 0-87169-651-7

- ^ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Bartl 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 53.

- ^ John Klassen, "The Nobility and the Making of the Hussite Revolution" (East European Quarterly/Columbia University Press, 1978)

- ^ "Joan of Arc's Letter to the Hussites (March 23, 1430)". archive.joan-of-arc.org.

- ^ a b Fudge, Thomas A. (1998). The magnificent ride : the first reformation in Hussite Bohemia. Internet Archive. Aldershot, Hants ; Brookfield, Vt. : Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-85928-372-1.

- ^ a b Malcolm Lambert (1992). Medieval heresy. Internet Archive. B. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-17431-8.

- ^ PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pp. 17–25, 33–45, 70–76, 159–184, 187–199

- ^ Sheldon, Addison Erwin; Sellers, James Lee; Olson, James C. (1993). Nebraska History, Volume 74. Nebraska State Historical Society. p. 151.

- ^ "Utraquism’s faithfulness to the Prague Use of the Roman rite…(was) an intentional symbol of Utraquism’s self-understanding as a continuing part of the Western Catholic Church." Holeton, David R.; Vlhová-Wörner, Hana; Bílková, Milena (2007). "The Trope Gregorius presul meritis in Bohemian Tradition: Its Origins, Development, Liturgical Function and Illustration" (PDF). Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice. 6: 215–246. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ "The Four Articles of Prague". John Hus: Apostle of Truth.

- ^ Cook, William R. (1973). "John Wyclif and Hussite Theology 1415–1436". Church History. 42 (3): 335–349. doi:10.2307/3164390. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3164390.

- ^ Profous, Antonín (1957). Místní jména v Čechách: Jejich vznik, původní význam a změny; part 4, S–Ž. Prague, Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

Bibliography

[edit]- Michael Van Dussen and Pavel Soukup (eds.). 2020. A Companion to the Hussites. Brill.

- Kaminsky, H. (1967) A History of the Hussite Revolution University of California Press: Los Angeles.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (1998) The Magnificent Ride: The First Reformation in Hussite Bohemia, Ashgate.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (2002) The Crusade against Heretics in Bohemia, Ashgate.

- Ondřej, Brodu, "Traktát mistra Ondřeje z Brodu o původu husitů" (Latin: "Visiones Ioannis, archiepiscopi Pragensis, et earundem explicaciones, alias Tractatus de origine Hussitarum"), Muzem husitského revolučního hnutí, Tábor, 1980, OCLC 28333729 in (in Latin) with introduction in (in Czech)

- Mathies, Christiane, "Kurfürstenbund und Königtum in der Zeit der Hussitenkriege: die kurfürstliche Reichspolitik gegen Sigmund im Kraftzentrum Mittelrhein," Selbstverlag der Gesellschaft für Mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte, Mainz, 1978, OCLC 05410832 in (in German)

- Bezold, Friedrich von, "König Sigmund und die Reichskriege gegen die Husiten," G. Olms, Hildesheim, 1978, ISBN 3-487-05967-3 in (in German)

- Denis, Ernest, "Huss et la Guerre des Hussites," AMS Press, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-404-16126-X in (in French)

- Klassen, John (1998) "Hus, the Hussites, and Bohemia" in New Cambridge Medieval History Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Macek, Josef, "Jean Huss et les Traditions Hussites: XVe–XIXe siècles," Plon, Paris, 1973, OCLC 905875 in (in French)

External links

[edit]- "Hussites". A Dictionary of All Religions and Religious Denominations (4th ed.). 1784.

- "Hussites". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Wilhelm, J. (1913). "Hussites". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Hussite Museum, Tabor

KSF

KSF