Hymnal

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A hymnal or hymnary is a collection of hymns, usually in the form of a book, called a hymnbook (or hymn book). They are used in congregational singing. A hymnal may contain only hymn texts (normal for most hymnals for most centuries of Christian history); written melodies are extra, and more recently harmony parts have also been provided.

Hymnals are omnipresent in churches but are not often discussed; nevertheless, liturgical scholar Massey H. Shepherd once observed: "In all periods of the Church's history, the theology of the people has been chiefly molded by their hymns."[1]

Elements and format

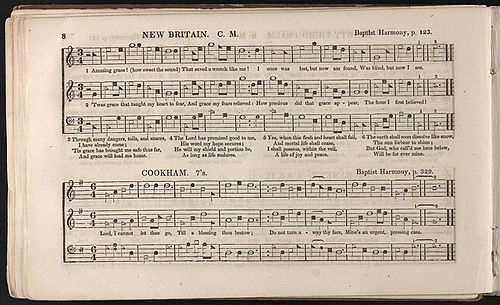

[edit]Since the twentieth century, singer-songwriter hymns have become common, but in previous centuries, generally poets wrote the words, and musicians wrote the tunes. The texts are known and indexed by their first lines ("incipits") and the hymn tunes are given names, sometimes geographical (the tune "New Britain" for the incipit "Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound"). The hymnal editors curate the texts and the tunes. They may take a well-known tune and associate it with new poetry, or edit the previous text; hymnal committees are typically staffed by both poets and musicians. Some hymnals are produced by church bodies and others by commercial publishers.

In large denominations, the hymnal may be part of a coordinated publication project that involves several books: the pew hymnal proper; an accompaniment version (e.g. using a ring binder so that individual hymns can be removed and sit nicely on a music stand); a leader's guide (e.g. matching hymns to lectionary readings); and a hymnal companion, providing descriptions about the context, origin and character of each hymn, with a focus on their poets and composers.

Service music

[edit]In some hymnals, the front section is occupied by service music, such as doxologies, three-fold and seven-fold amens, or entire orders of worship (Gradual, Alleluia, etc.). A section of responsorial psalms may also be included.

Indexes

[edit]Hymnals usually contain one or more indexes; some of the specialized indexes may be printed in the companion volumes rather than the hymnal itself. A first line index is almost universal. There may also be indexes for the first line of every stanza, the first lines of choruses, tune names, and a metrical index (tunes by common meter, short meter, etc.). Indexes for composers, poets, arrangers, translators, and song sources may be separate or combined. Lists of copyright acknowledgements are essential. Few other books are so well indexed; at the same time, few other books are so well memorized. Singers often have the song number of their favorite hymns memorized, as well as the words of other hymns. In this sense, a hymnal is the intersection of advanced literate culture with the persistent survival or oral traditions into the present day.

History

[edit]

Origins in Europe

[edit]The earliest hand-written hymnals are from the Middle Ages in the context of European Christianity, although individual hymns such as the Te Deum go back much further. The Reformation in the 16th century, together with the growing popularity of moveable type, quickly made hymnals a standard feature of Christian worship in all major denominations of Western and Central Europe. The first known printed hymnal was issued in 1501 in Prague by Czech Brethren (a small radical religious group of the Bohemian Reformation) but it contains only texts of sacred songs.[2] The Ausbund, an Anabaptist hymnal published in 1564, is still used by the Amish, making it the oldest hymnal in continuous use. The first hymnal of the Lutheran Reformation was Achtliederbuch, followed by the Erfurt Enchiridion. An important hymnal of the 17th century was Praxis pietatis melica.

Hymnals in Early America

[edit]Market forces rather than denominational control have characterized the history of hymnals in the thirteen colonies and the antebellum United States; even today, denominations must yield to popular tastes and include "beloved hymns" such as Amazing Grace[3] and Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing,[4] in their hymnals, regardless of whether the song texts conform to sectarian teaching.

The first hymnal, and also the first book, printed in British North America, is the Bay Psalm Book, printed in 1640 in Cambridge, Massachusetts,[5][6] a metrical Psalter that attempted to translate the psalms into English so close to the original Hebrew that it was unsingable. The market demand created by this failure, and the dismal nature of Calvinist "lining out the psalms" in general, was served by hymnals for West gallery singing imported from England.

William Billings of Boston took the first step beyond West Gallery music in publishing The New-England Psalm-Singer (1770), the first book in which tunes were entirely composed by an American.[7] The tune-books of Billings and other Yankee tunesmiths were widely sold by itinerant singing-school teachers. The song texts were predominantly drawn from English metrical psalms, particularly those of Isaac Watts. All of the publications of these tunesmiths (also called "First New England School") were essentially hymnals.

In 1801, the tunebook market was greatly expanded by the invention of shape notes, which made it easier to learn how to read music. John Wyeth, a Unitarian printer in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who had apprenticed in Boston during the emergence of the First New England School, began to publish tunebooks in 1810 in German and English for various sectarian groups (but not Unitarians). He saw a virgin market in the Methodist and Baptist revival movement. Singing in these camp meetings was chaotic because multiple tunes were sung simultaneously for any given hymn text. Since he lacked musical training, Wyeth employed Elkanah Kelsey Dare to collect tunes and edit them. Wyeth's Repository of Music, Part Second (1813) included 41 folk tunes, the first printed in America. This was also the birth of the "folk hymn": the use of a folk tune, collected and harmonized by a trained musician, printed with a hymn text.[8] "Nettleton," the tune used in North America to sing "Come Thou Fount" (words written in 1758), first appeared here.

Southern Shape Note Hymnals (Tunebooks)

[edit]

Southerners identified with folk hymns of Wyeth's 1813 Part Second and collected more: the titles of Kentucky Harmony (1816) of Ananias Davisson, the Tennessee Harmony (1818) of Alexander Johnson, the Missouri Harmony (1820) of Allen D. Carden. and the Southern Harmony (1835) of William Walker drew attention to the fact that they contained regional folk songs for singing in two, three, or four parts. A new direction was taken by B. F. White with the publication of the Sacred Harp (1844): whereas others had gone on to produce a series of tunebooks, White stopped at one, then spent the rest of his life building an organization, modeled on church conventions, to organize singing events, with the result that the Sacred Harp continues as a living tradition to the present. The other tunebooks eventually yielded to denominational hymnals that became pervasive with the development of railroad networks, with the exception of the Southern Harmony, for which there is an annual singing in Benton, Kentucky to the present day, and Walker's Christian Harmony, published in 1866, with the first convention organized in 1875 (43 all-day singings in 2010); the Kentucky Harmony was republished in altered form as the Shenandoah Harmony in 2010, reviving the world of predominantly minor key melodies and unusual tonalities of Davisson's work.

The Better Music Movement in the Industrialized North

[edit]In the North, the "Better Music Boys," cultivated musicians such as Lowell Mason and Thomas Hastings who turned to Europe for musical inspiration, introduced musical education into the school system, and emphasized the use of organs, choirs, and "special music." In the long term this resulted in a decline of congregational singing. On the other hand, they also composed hymns that could be sung by everybody. Mason's The Handel and Haydn Society Collection of Church Music (1822) was published by the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston while Mason was still living in Savannah; nobody else would publish it. This never became a denominational hymnal but was well-received by choirs. Mason's famous hymns, which were also included in Southern tunebooks, appeared later editions or publications: Laban ("My soul, be on thy guard;" 1830), Hebron ("Thus far the Lord hath led me on," 1830), Boylston ("My God, my life, my love," 1832), Shawmut ("Oh that I could repent! 1835") Bethany ("Nearer, My God, to Thee", as sung in the United States) (1856).

Hymns Ancient and Modern appears in England

[edit]In England, the growing popularity of hymns inspired the publication of more than 100 hymnals during the period 1810–1850.[9] The sheer number of these collections prevented any one of them from being successful.[10] In 1861, members of the Oxford Movement published Hymns Ancient and Modern under the musical supervision of William Henry Monk,[11] with 273 hymns. For the first time, translations from languages other than Hebrew appeared, the "Ancient" in the title referring to the appearance of Phos Hilaron, translated from Greek by John Keble, and many hymns translated from Latin. This was a game-changer. The Hymns Ancient and Modern experienced immediate and overwhelming success.[10] Total sales in 150 years were over 170 million copies.[11] As such, it set the standard for many later hymnals on both sides of the Atlantic.[10] English-speaking Lutherans in America began singing the metrical translations of German chorales by Catherine Winkworth and Jane Laurie Borthwick, and rediscovered their heritage. Although closely associated with the Church of England, Hymns Ancient and Modern was a private venture by a committee, called the Proprietors, chaired by Sir Henry Baker.[11]

See also

[edit]- List of Chinese hymn books

- List of English-language hymnals by denomination

- Hymnody of continental Europe

References

[edit]- ^ Shepherd, Massey Hamilton (1961). "The Formation and Influence of the Antiochene Liturgy". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 15: 37. doi:10.2307/1291174. JSTOR 1291174.

- ^ Settari, Olga (1994). "The Czech sacred song from the period of the Reformation" (PDF). Sborník prací filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity. Studia minora facultatis philosophicae universitatis Brunensis. H 29.

- ^ For example, strictly speaking, Lutherans should not sing "grace... taught my heart to fear," because they believe that it is the Word of God, ministered through divine grace, that teaches the heart and mind. The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod resisted until the 2005 publication of Christian Worship: A Lutheran Hymnal. Almost all hymnal committees choose to omit the final, apocalyptic verse ("The earth will soon dissolve like snow").

- ^ Every hymnal committee edits this a different way.

- ^ Murray, Stuart A. P. (2009). The Library An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 9781602397064.

- ^ "The Bay Psalm Book". World Digital Library. Library of Congress. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ McKay, David P.; Crawford, Richard (1975). William Billings of Boston. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09118-8.

- ^ The hymn text was usually literary: Watts, Wesley, and Newton being the most popular.

- ^ Julian, John (1892). Dictionary of Hymnology. John Murray.

- ^ a b c Eskew, Harry; McElrath, Hugh T. (1995). Sing with Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Hymnology. Nashville: Church Street Press. pp. 135–139. ISBN 9780805498257.

- ^ a b c "The History and Traditions". Hymns Ancient & Modern. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

External links

[edit]- "SDA Hymnal online"

- "Hymnary.org". Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2020-01-19. — Extensive database of hymns and hymnology resources; incorporates the Dictionary of North American Hymnology, a comprehensive database of North American hymnals published before 1978.

- "SDA Hymnal Songs"

KSF

KSF