Individual action on climate change

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 52 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 52 min

Individual action on climate change describes the personal choices that everyone can make to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of their lifestyles and catalyze climate action. These actions can focus directly on how choices create emissions, such as reducing consumption of meat or flying, or can focus more on inviting political action on climate or creating greater awareness how society can become more green.

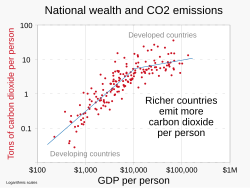

Excessive consumption is one of the most significant contributors to climate change and other environmental issue than population increase, although some experts contend that population remains a significant factor.[1] High consumption lifestyles have a greater environmental impact, with the richest 10% of people emitting about half the total lifestyle emissions.[2][3] Creating changes in personal lifestyle, can change social and market conditions leading to less environmental impact. People who wish to reduce their carbon footprint (particularly those in high income countries with high consumption lifestyles), can for example reduce their air travel for holidays, use bicycles instead of cars on a daily basis, eat a plant-based diet, and use consumer products for longer.[4] Avoiding meat and dairy products has been called "the single biggest way" individuals can reduce their environmental impacts.[5]

Some commentators say that actions taken by individual consumers, such as adopting a sustainable lifestyle, are insignificant compared to actions on the political level.[6] Others say that individual action does lead to collective action because "lifestyle change can build momentum for systemic change."[7][8] Other commentors have highlighted how the concept of individual carbon footprint was advanced by fossil fuel companies, like British Petroleum in order to reduce the culpability of fossil fuel companies.[9][10]

Suggested individual target amount

[edit]

As of 2021[update] the remaining carbon budget for a 50-50 chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of warming is 460 bn tonnes of CO2 or 11+1⁄2 years at 2020 emission rates.[14] Global average greenhouse gas per person per year in the late 2010s was about 7 tonnes[15] – including 0.7 tonnes CO2eq food, 1.1 tonnes from the home, and 0.8 tonnes from transport.[16] Of this about 5 tonnes was actual carbon dioxide.[17] To meet the Paris Agreement target of under 1.5 degrees warming by the end of the century, it is estimated that the annual carbon footprint per person required by 2030 is 2.3 tonnes.[18][needs update] As of 2020[update] the average Indian almost meets this target,[19] the average person in France[20] or China overshoots it, and the average person in the US and Australia vastly overshoots it. Per capita emissions also vary significantly within countries, with wealthier individuals creating more emissions.[21][22] A 2015 Oxfam report calculated that the wealthiest 10% of the global population were responsible for half of all greenhouse gas emissions.[23] According to a 2021 report by the UN, the wealthiest 5% contributed nearly 40% of emissions growth from 1990 to 2015.[24]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report pointed out in 2022: "To enhance well-being, people demand services and not primary energy and physical resources per se. Focusing on demand for services and the different social and political roles people play broadens the participation in climate action."[25]: TS-98 The report explains that behavior, lifestyle, and cultural change have a high climate change mitigation potential in some sectors, particularly when complementing technological and structural change.[26]: 5–3

Meaning of "lifestyle carbon footprint"

[edit]The carbon footprint was originally coined and popularized by the ad campaign Beyond Petroleum in 2004–2006, funded by British Petroleum (BP), for which other have accused them of popularizing to downplay their own culpability.[9][10]

In 2008 the World Health Organization wrote that "Your 'carbon footprint' is a measure of the impact your activities have on the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) produced through the burning of fossil fuels".[27] In 2019 the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies in Japan defined "lifestyle carbon footprint" as "GHG emissions directly emitted and indirectly induced from the final consumption of households, excluding those induced by government consumption and capital formation such as infrastructure."[28]: v However an Oxfam and SEI study in 2020 estimated per capita CO2 emissions rather than CO2-equivalent, and allocated all consumption emissions to individuals rather than just household consumption.[29] According to a 2020 review many academic studies do not properly explain the scope of the "personal carbon footprint" they study.[30]

Travel and commuting

[edit]A comparison of travel options shows:

- Walking and running are among the least environmentally harmful modes of transportation.

- Cycling follows walking and running as having a low impact on the environment.

- Public transport such as electric buses, metro and electric trains generally emit less greenhouse gases than cars per passenger.

Walking and biking

[edit]Walking and biking emit little to no greenhouse gases and are healthy alternatives to driving or riding public transportation.[31] There are also increasing numbers of bike-sharing services in urban environments.[32]

Public transport

[edit]Reliable public transportation can be one of the most viable alternatives to driving personal vehicles.[33] While there are efficiency problems associated with public transportation (waiting times, missed transfers, unreliable schedules, energy consumption), they can be improved as funding and public interest increases and technology advances.[34]

A 2022 survey found that 33% of car buyers in Europe will opt for a petrol or diesel car when purchasing a new vehicle. 67% of the respondents mentioned opting for the hybrid or electric version.[35][36] In the EU, only 13% of the total population do not plan on owning a vehicle at all.[35] 44% of Chinese car buyers, on the other hand, are the most likely to buy an electric car.[35][37]

Electric cars

[edit]

There are many options to choose from when considering alternatives to personal car use, but the use of a personal vehicle may be necessary due to location and accessibility reasons.[38] The life cycle assessment of a vehicle evaluates the environmental impact of the production of the vehicle and its spare parts, the fuel consumption of the vehicle, and what happens to the vehicle at the end of its lifespan.[39] These environmental impacts can be measured in greenhouse gas emissions, solid waste produced, and consumption of energy resources among other factors.[40][39] Increasingly common alternatives to internal-combustion engines vehicles are electric vehicles (EVs), and hybrid-electric vehicles.[41]

Carpooling and ride-sharing services

[edit]Carpooling and ride-sharing services are also alternatives to personal transportation. Carpooling reduces the number of cars on the road, in turn reducing the amount of traffic and energy consumption.[42]

Car ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft could be viable options for transportation, but according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, ride-share service trips currently result in an estimated 69% increase in climate pollution on average.[43] There are more vehicles on the road as a result of passengers who would have otherwise taken public transportation, walked, or biked to their destination.[43] Ride-sharing services can reduce emissions if they implement strategies like electrifying vehicles and increase carpooling trips.[43]

Air transport

[edit]Air travel is one of the most emission-intensive modes of transportation.[44] The current most effective way to reduce personal emissions from air travel is to fly less.[45][46] New technologies are being developed to allow for more efficient fuel consumption and planes powered by electricity.[46]

Avoiding air travel and particularly frequent flyer programs[47] has a high benefit because the convenience makes frequent, long-distance travel easy, and high-altitude emissions are more potent for the climate than the same emissions made at ground level. Aviation is much more difficult to fix technically than surface transport,[48] so will need more individual action in future if the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation cannot be made to work properly.[49]

Flying is responsible for 5 percent of global warming.[50] Compared to longer flight routes, shorter flights actually produce larger amounts of greenhouse gas emissions per passenger they carry and mile covered, so individuals may consider train travel instead but this can be more expensive due to aviation subsidies.[51] Airplanes contribute to damaging our environment since airplanes cause greater air pollution as they release carbon dioxide along with nitrogen oxides, which is an atmospheric pollutant. Exhaust emissions lead to changes in the amounts of the greenhouse gases ozone and methane.[52] Avoiding night-flights may help, as contrails may account for over half of aviation's climate change impact.[53]

Climate change is a factor that 67% of Europeans consider when choosing where to go on holiday. 52% of Europeans, specifically 37% of people ages 30–64 and 25% of people aged above 65, state that in 2022 they will choose to travel by plane. 27% of young people claim they will travel to a faraway destination. More specifically, people under the age of 30 are more likely to consider climate implications of vacation spots and air travel.[54][55]

Home energy and landscaping

[edit]

Reducing home energy use through measures such as insulation, better energy efficiency of appliances, cool roofs, heat reflective paints,[56] lowering water heater temperature, and improving heating and cooling efficiency can significantly reduce an individual's carbon footprint.[57] After home insulation and ventilation has been checked, replacing a failed gas boiler with a heat pump makes a considerable difference,[58] especially in climates where both heating and cooling are required.[59]

In addition, the choice of energy used to heat, cool, and power homes makes a difference in the carbon footprint of individual homes.[60] Many energy suppliers in various countries worldwide have options to purchase part or pure "green energy" (usually electricity but occasionally also gas).[61] These methods of energy production emit almost no greenhouse gases once they are up and running.

Installing rooftop solar, both on a household and community scale, also drastically reduces household emissions, and at scale could be a major contributor to greenhouse gas abatement.[62][63]

Low energy products and consumption

[edit]

Labels, such as Energy Star in the US, can be seen on many household appliances, home electronics, office equipment, heating and cooling equipment, windows, residential light fixtures, and other products. Energy star is a program in the U.S. that promotes energy efficiency. When buying air conditioning the choice of coolant is important.[65]

Carbon emission labels describe the carbon dioxide emissions created as a by-product of manufacturing, transporting, or disposing of a consumer product. Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) "present transparent, verified and comparable information about the life-cycle environmental impact of products".[66] These labels may help consumers choose lower energy products.

Converting appliances such as stoves, water heaters and furnaces from gas to electric reduces emissions of CO2 and methane.[67]

Landscape and gardens

[edit]Plants process carbon dioxide to make organic molecules like cellulose, sugars, starches, plant proteins, and oils. Perennials keep a large proportion of those organic molecules for as long as they live, not releasing them until microorganisms decompose them after they die. Perennial plants like trees and shrubs contribute to the absorption of carbon dioxide from the air.[68][69]

Annual plants that die each year release almost all of the CO2 that they take in. Grass lawns that live over the winter but die back above ground can also soak up a share of carbon dioxide, reducing that greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. However, both organic and synthetic fertilizers are sources of NOx, and turfgrass lawns use 3 million tons of nitrogen-based fertilizer each year. That adds four to five tons of carbon to the atmosphere for every ton of nitrogen (660,000 tons of carbon dioxide/year). NOx is about 300 times more heat-absorbing than carbon dioxide.[70][71]

Soil microbes break down organic carbon into carbon dioxide. Reducing irrigation would slow the microbial activity of the soil and its production of carbon dioxide.[69] However, increased irrigation is required for lawn maintenance in areas that are becoming more arid due to climate change. Gas-powered lawnmowers and other power tools used for lawn maintenance produce carbon dioxide and methane, which are greenhouse gases.[70]

Lawns management methods like fertilizers and fossil fuel-powered lawn equipment may outweigh any carbon sequestration from the perennial grass lawn.[71] Reducing irrigation, nitrogen fertilizer, chemical pesticides, and using hand tools instead of power tools that use fossil fuels can all reduce the climate impact of lawns.[72]

Natural lawns promote pollination, require no fertilization, require less frequent mowing, promote diversity, and use less water.[73] There are many opportunities to plant trees and shrubs in the yard, along roads, in parks, and in public gardens. In addition, some charities plant fast-growing trees to help people in places with less tree coverage to restore the productivity of their lands.[74] Individuals can also plant home vegetable gardens that provide locally grown food, native plant gardens that provide a diversity of species, and trees and perennial shrubs that develop sustainable carbon sequestration.[71]

Laundry and choice of clothing

[edit]Hanging laundry to dry saves energy that would have been used for heating, reducing clothing's carbon footprint.[75][76][77][78] Additionally, using a shorter, cold water wash cycle can conserve energy by as much as 66%.[79]

Purchasing well-made, durable clothing, and avoiding "fast fashion" is critical for reducing climate impact.[80][81][82] Some clothing is donated and/or recycled, meanwhile, the rest of the waste heads to landfills where they release "greenhouse gases".[83]

Hot water consumption

[edit]Domestic heated water using non-renewable resources such as gas contributes to significant global carbon dioxide emissions. As of 2020, most homes use gas or electric boilers to heat their water. Powering these boilers with renewable energy would reduce these emissions, although the cost of installation means this is not a universally viable option.[84] Turning off the water heater and using unheated water for laundry, bathing (weather permitting), dishes, and cleaning eliminates those emissions.

Demand reduction

[edit]Less consumption of goods and services

[edit]The production of many goods and services results in the emission of greenhouse gases as well as pollution. One way for individuals to decrease their environmental footprint is by consuming less goods and services. Decreasing the consumption of goods and services results in a lower demand, and lower supply (production) follows.[85] Individuals can prioritize shrinking the consumption of those goods and services whose production results in relatively high pollution levels. Individuals can also prioritize discontinuing the use of those goods and services that offer little to no real utility by "speaking with their money", since unpopular products neither satisfy consumer wants/needs nor the environment's; however, government subsidies may prove "boycott buying" to be futile in some cases, enabling the producer.[86][87][88]

A climate survey found that in 2021 42% of Europeans, specifically 48% of women and 34% of men, already invest in second-hand clothing rather than buying new ones. Populations aged 15 to 29, are found more likely to do so.[89][90] Education on sustainable consumption, specifically targeting children, is seen as a priority by 93% of Chinese citizens, 92% of EU, 88% of British citizens and 81% of Americans.[91][92]

The National Geographic Society has concluded that city dwellers can help with climate change if they (or we) simply "buy less stuff".[93]

Lloyd Alter suggests that one way to get a practical sense of embodied carbon is to ask, "How much does your household weigh?"[94]

For-profit companies usually promote and market their products as useful or needed to potential consumers, even when they in reality are harmful or wasteful to them and/or the environment. Individuals should be diligent in self-assessing and/or researching whether or not each product they purchase and consume is really of value to decrease consumption. If a gas stove or other type of stove needs to be replaced in a new house, then an electric stove is preferable. However, as cooking is usually a small part of household GHG emissions, it is generally not worth changing a stove simply for climate reasons.[95]

Using durable reusable containers such as lunchboxes, "single-use" grocery and produce bags (can be used as light-duty trash bags), Tupperware, as well as buying local produce, minimally packaged foods and general items, all reduce carbon emissions and pollution from the production of single use containers and packaging. These tactics mitigate GHG production by reducing demand for extra packaging and shipping of products.[96][97]

Reducing food loss

[edit]The world's food production is responsible for approximately a quarter of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by humanity each year,[98] with livestock alone accounting for 14.5% of the total greenhouse gas emissions.[99] The carbon dioxide emissions associated with food are estimated to be 2.2 tons per person annually, from production to consumption.[100] If this is correct, it would mean that just the food aspect of daily life would nearly exhaust the entire Paris Agreement compliance goal of 2.3 tons [101] per person per year. Therefore, reducing food loss[102] is absolutely essential, and in the 2020 Project Drawdown, it was identified as the top priority solution to address climate change.[103] Fortunately, out of the 2.2 tons mentioned, 1.9 tons are considered reducible.[100]

According to a 2023 study published in Nature Food, carbon dioxide emissions resulting from food waste make up half of the total emissions in the entire food system.[104] In the United States, it is estimated that 31% of food delivered to retail stores is discarded by either retailers or consumers.[105] Furthermore, the carbon dioxide emissions from food waste that decomposes in landfills, etc., amount to 2.5 kilograms of carbon dioxide per kilogram of food and also produce methane, a greenhouse gas with 25 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide.[106]

Food waste also represents a loss of the energy to transport foods from producers to consumers. According to a study published in Nature Food in 2022, transportation-related emissions for food from producers to retail stores represent around 20% of the total emissions for vegetables and fruits,[107] while for refrigerated transport of items like meat, fresh fish, and dairy, it increases by an additional 20–30%.[108]

In addition to the waste of food itself, the disposal of packaging materials is also a significant concern. Reducing food waste contributes to reducing both global warming and environmental pollution caused by plastic packaging materials. It is estimated that approximately 5% of the energy used to manufacture and distribute food products is attributed to packaging materials.[109] Plastic food packaging materials are known for their significant environmental pollution, therefore they contribute not only to carbon dioxide emissions associated with plastic production but also to overall adverse environmental impacts.[110] Japan's excessive packaging culture in the context of food, has been criticized internationally in relation to Japanese plastic waste.[111][112][113][114]

Eating a plant-rich diet

[edit]

The world's food system is responsible for about one-quarter of the planet-warming greenhouse gases that humans generate each year[115] with the livestock sector alone contributing 14.5% of all anthropogenic GHG emissions.[116] The 2019 World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency, endorsed by over 11,000 scientists from more than 150 countries, stated that "eating mostly plant-based foods while reducing the global consumption of animal products, especially ruminant livestock, can improve human health and significantly lower GHG emissions."[117] The most common ruminant livestock are cattle and sheep.

Agriculture is very difficult to fix technically so will need more individual action[118] or carbon offsetting than all other sectors except perhaps aviation.[48]

Eating less meat, especially beef and lamb, reduces emissions.[119] A diet which is part of individual action on climate change is also good for health, averaging less than 15 g (about half an ounce) of red meat and 250 g dairy (about one glass of milk) per day.[120] The World Health Organization recommends trans-fats make up less than 1% of total energy intake: ruminant trans-fats are found in beef, lamb, milk and cheese.[121] The Special Report on Climate Change and Land says that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Ecologist Hans-Otto Pörtner, who contributed to the report, said "We don't want to tell people what to eat, but it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect."[122]

Meats such as beef have a higher climate impact since cows release methane, a greenhouse gas that is more harmful in the short-term than carbon dioxide.[123]

Eating a plant-rich diet is listed as the #1 individual solution for climate change as modeled by Project Drawdown, based on avoided emissions from the production of animals and avoided emissions from additional deforestation for grazing land.[124]

A 2018 study indicated that one fifth of Americans are responsible for about half of the country's diet-related carbon emissions, due mostly to eating high levels of meat, especially beef.[125][126]

A 2022 study published in Nature Food found that if high-income nations switched to a plant-based diet, vast amounts of land used for animal agriculture could be allowed to return to their natural state, which in turn has the potential to sequester 100 billion tons of CO2 by 2100. In addition to mitigating climate change, other benefits of this transition would include improved water quality, restoration of biodiversity, and reductions in air pollution.[127][128]

A 2022 survey found that half of Europeans (51%) support reducing the amount of meat and dairy products people may buy to combat climate change (11% more than Americans, who support it at 40%, but far lower than Chinese people, who support it at 73%). The same survey found that to assist individuals make more sustainable food decisions, 79% of Europeans support labelling all food with their carbon footprint (Americans support it at 62%, but Chinese respondents support it at 88%).[129]

A 2023 paper published in Nature Food found that vegan diets reduce emissions, water pollution and land use by 75%, while also significantly reducing the destruction of wildlife and water usage.[130]

Eating beef is the worst dietary habit

[edit]

The majority of greenhouse gas emissions from food production come from land use change and farm-level processes. Farm-level emissions include both organic (manure management) and synthetic fertilizer applications, as well as ruminant enteric fermentation methane production. Together, these account for more than 80% of the carbon footprint of most foods. The largest meta-analysis of the global food system, published in Science in 2018, using data from over 38,000 commercial farms in 19 countries, estimated the total greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of diverse foods.[133] Carbon dioxide is the most important greenhouse gas, but not the only one, and agriculture is a large source of methane and nitrous oxide, which are much more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. To capture all greenhouse gas emissions associated with these food production processes, the carbon footprint is expressed in kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent, taking into account all greenhouse gases besides carbon dioxide.

Animal foods have a much larger carbon footprint than plant foods. Beef is the worst, with an equivalent carbon dioxide emission of 99.5 kg per kilogram of production. For lamb, it is 39.7 kg, for cheese, 23.9 kg, for pork, 12.3 kg, for chicken, 9.9 kg, and for peas, it is just 0.98 kg.[133] If we compare the equivalent carbon dioxide emission per 100 grams of protein from a food to compare nutritional value, beef is 49.9 kg, pork is 7.6 kg, chicken is 5.7 kg, and peas is 0.44 kg.[133] The reasons for beef’s particular inefficiency as a food source are the vast land and water resources (i.e., virtual water ) required for cattle farming and the fact that cattle emit methane, a greenhouse gas.

The impact of food production is more realistic and tangible when expressed in terms of carbon dioxide emissions per serving rather than per weight. For example, a cheeseburger, a popular beef food, is estimated to emit about 4.79 pounds (2.17 kg)[134] or 1.9 kg of carbon dioxide per serving,[135] which is about 10 times the weight of the cheeseburger that emitted the carbon dioxide, which is the equivalent of driving about 5 miles (8 km) in a car. [136] Other estimates put the total carbon dioxide emissions at 3.6 to 6.1 kg per serving. If we convert this into the amount of greenhouse gases emitted each year from the annual consumption of cheeseburgers in the United States, it is equivalent to the amount emitted by 6.5 to 19.6 million SUVs. [137]

On the other hand, the carbon footprint of food transportation is relatively small compared to that of production, and because the production footprint of beef and dairy products is so large as mentioned above, transportation typically accounts for less than 1% of beef’s greenhouse gas emissions,[133] meaning that even if beef is consumed close to where it is produced, any carbon footprint reduction would be negligible.

Moderate drinking is good for the planet's health too

[edit]Alcoholic beverage production is a resource- and energy-intensive process with a large carbon footprint.[138][139] Alcoholic beverages are produced from agricultural crops, which generate carbon dioxide (and nitrogen oxides and methane) emissions from agricultural production, as well as energy and large amounts of water for brewing and bottling. In addition to the resource consumption associated with production, food miles generated by transporting beverage products and waste generated from packaging are also significant issues.[140] While glass bottles and aluminum cans are recyclable, the packaging that holds them together, such as six-pack rings , is a significant source of plastic pollution and carbon dioxide emissions. [141] Thus, the carbon footprint of alcoholic beverage production is extensive and significant.[142][143][144][145][146][147]

Although beer generally requires less energy to produce than wine or spirits, [148] the equivalent carbon dioxide emissions for industrial production are estimated at around 640–760 grams per 500 milliliters of beer, [149] which is more than the weight of the beer itself. In addition, beer is a mass-consumption beverage, which requires large-scale production, heavy product transportation, and energy-intensive refrigeration, which further increase the carbon dioxide emissions per final bottle. [150] While metal barrel (keg) catering products have a smaller carbon footprint for packaging and transportation than bottled or canned products (one estimate is that a 30-liter keg is 2.7 times smaller than a 330-ml bottle,[151] they are not readily applicable to the consumer market.

In the production of low-carb light beer, brewing enzymes are used to break down most of the carbohydrates into monosaccharides, which are then fermented by yeast into alcohol and carbon dioxide,[152] but as of 2024 it has not been estimated whether this series of production processes is more advantageous in reducing carbon dioxide emissions than that of regular beer. On the other hand, non-alcoholic beer requires a shorter fermentation process than regular beer, but is often produced by removing alcohol from the beer,[153][154] and the additional energy costs involved can increase the carbon footprint. [155] To avoid this problem, a special yeast strain that can brew non-alcoholic beer without the alcohol removal process [156] has been used, which has been reported to reduce the equivalent carbon dioxide emissions by 1,260 tons per 10,000 kiloliters of beer with an alcohol content of <0.05%. [157] In other words, the carbon dioxide emissions from alcohol removal per 500 milliliters are 63 grams, which is estimated to be about 10% higher than the carbon dioxide emissions from the production of regular beer mentioned above.

Wine, especially when produced by large commercial wineries, is associated with grape farming, producing large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions and polluted wastewater. [158] The wine-making process is energy-intensive, involving fermentation, rigorous aging, bottling and storage. Although wine is not mass-produced like beer, it is usually bottled in heavy glass bottles,[159] resulting in a heavy product that is often exported long distances internationally, with the added waste from the special packaging for transport and food miles from heavy packaging. To make matters worse, red wine is often bottled in green-colored glass, which is more difficult to recycle than clear-colored glass bottles, necessitating the production of new glass bottles, which consumes large amounts of energy.[160]

Wine products vary widely from low-cost to high-end, and carbon footprints can vary widely from product to product. One review estimated the carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per bottle (750 ml) of wine to be between 0.15 and 3.51 kilograms,[161] but it is difficult for the average consumer to determine which wines have a low carbon footprint. However, according to one estimate, the stages of the wine 'lifecycle' that have the largest carbon dioxide emissions are from grape farming (43.11%) and bottling and transportation (56.71%),[162] therefore choosing wine made from sustainably produced grapes (organic wine) or wine in a simple carton can reduce the carbon footprint. One estimate found that organic red wine, conventionally produced red wine, and white wine had carbon dioxide equivalent emissions of 1.02, 1.25, and 1.62 kilograms per bottle (750 ml), respectively .[163]

Spirits such as whiskey, vodka, rum, and gin have a larger carbon footprint per bottle than beer or wine.[164] This is mainly due to the large amount of carbon dioxide emitted by the distillation process, which is further exacerbated by the temperature and humidity control in warehouses where barrels of whiskey and other spirits are aged for long periods. In addition, many spirits products are bottled in thick glass bottles made specifically for each product, and the carbon footprint of their production also has an impact on the environment, and to make matters worse, some cheaper spirits products even use unsustainable plastic bottles.

However, spirits are not consumed in large quantities like beer or wine, and so may have a lower carbon footprint per standard consumption: one estimate puts the equivalent carbon dioxide emissions of a standard 350 ml glass of 3.5% light beer at about 280 grams, a 150 ml glass of wine at about 320 grams, and a 40 ml glass of spirits at about 90 grams on average.[165] Since all three contain roughly the same amount of alcohol, spirits with water are more effective at reducing global warming per unit of alcohol consumed than beer or wine.

The alcoholic beverage industry as a whole, including pubs , bars and other food and beverage businesses, contributes significantly to carbon dioxide emissions more than any individual product, and as mentioned above, this impact comes not only from production but also from advertising, logistics, packaging and waste disposal. Given the scale of the industry, if individuals practice environmentally conscious alcohol consumption behavior and the industry promotes efforts to minimize its impact on the environment, the effect on curbing global warming for society as a whole could be significant.

Family planning aspects

[edit]Worldwide population growth is considered to be a challenge for climate change mitigation.[166][1] Proposed measures include an improved access to family planning and access of women to education and economic opportunities.[167][168][169] Targeting natalistic politics involves cultural, ethical and societal issues. Various religions discourage or prohibit some or all forms of birth control.[170] Although having fewer children is perhaps the individual action that most effectively reduces a person's climate impact, the issue is rarely raised, and it is arguably controversial due to its private nature. Even so, ethicists,[171][172] some politicians such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,[173] and others[174][175][176][177] have started discussing the climate implications associated with reproduction. Researchers have found that some people (in wealthy countries) are having fewer children due to their beliefs that they can do more to slow climate change if they do not have children.[178]

Two interrelated aspects of this action, family planning and women and girl's education, are modeled by Project Drawdown as the #6 and #7 top potential solutions for climate change, based on the ability of family planning and education to reduce the growth of the overall global population.[179][180] In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss". The policies they promote, which "are proven and effective policies that strengthen human rights while lowering fertility rates", would include removing barriers to gender equality, especially in education, and ensuring family planning services are available to all.[181][182]

In a 2021 paper it was said that "human population has been mostly ignored with regard to climate policy" and attribute this to the taboo nature of the issue given its association with population policies of the past, including forced sterilization campaigns and China's one-child policy.[183][184] In 2022, a group of scientists urged families around the world to have no more than one child as part of the transformative changes needed to mitigate both climate change and biodiversity loss.[185] However, because climate change needs to be limited within the next few decades, having fewer children now might not make much difference.[186]

However the "per person carbon footprint" of individual people is likely to reduce over time due to efforts to decarbonize our economies and reach net zero emissions in the future.[187]: 113

Others

[edit]Personal finance

[edit]Individuals can check whether the financial companies they are using are part of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero,[188] and consider switching pensions, insurance and investments.[189] Donating to climate change charities has been suggested.[190]

Digital services and cryptocurrencies

[edit]Cryptocurrencies which are made by proof-of-work such as Bitcoin, are high carbon both because they use dirty electricity, such as electricity from Kazakhstan (some electricity in the United States used for Bitcoin mining is also dirty[191] but the gas might be burned anyway[192]) and because cryptocurrency mining uses hardware for only a short time before it becomes ewaste.[193][194] Individuals with such cryptocurrency can switch to proof of stake crypto such as Tezos or ethereum.[195] Individuals can also decide to not invest in cryptocurrencies at all.

Political advocacy

[edit]

Impactful ways in the area of political advocacy that an individual can take include:[196] individual citizen participation in groups advocating for collective action in the form of political solutions, such as carbon pricing, meat pricing,[197] ending subsidies for fossil fuels[198] and animal husbandry,[199] and ending laws encouraging car use.[200]

Activist movements

[edit]

Climate change is a prevalent issue in many societies.[202] Some believe that some of the long-term negative effects of climate change can be ameliorated through individual and community actions to reduce resource consumption. Thus, many environmental advocacy organizations associated with the climate movement (such as the Earth Day Network) focus on encouraging such individual conservation and grassroots organizing around environmental issues.[203][204]

To raise awareness of climate issues, activists organized a series of international labor and school strikes in late September 2019,[205] with estimates of total participants ranging between 6 and 7.3 million.[206][207]

A number of groups from around the world have come together to work on the issue of global warming. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from diverse fields of work have united on this issue. A coalition of 50 NGOs called Stop Climate Chaos launched in Britain in 2005 to highlight the issue of climate change.

The Campaign against Climate Change was created to focus purely on the issue of climate change and to pressure governments into action by building a protest movement of sufficient magnitude to effect political change.

Following environmentalist Bill McKibben's mantra that "if it's wrong to wreck the climate, it's wrong to profit from that wreckage",[208] fossil fuel divestment campaigns attempt to get public institutions, such as universities and churches, to remove investment assets from fossil fuel companies. By December 2016, a total of 688 institutions and over 58,000 individuals representing $5.5 trillion in assets worldwide had been divested from fossil fuels.[209][210]

A 2023 review study published in One Earth stated that opinion polls show that most people perceive climate change as occurring now and close by.[211] The study concluded that seeing climate change as more distant does not necessarily result in less climate action, and reducing psychological distancing does not reliably increase climate action.[211]

Reform of subsidies and taxes

[edit]Political advocacy can focus on removing those fossil fuel and other subsidies, and taxes which discourage individual action on climate change, for example:

- Abolish a subsidy of kerosene because this subsidy discourages individuals switching to other fuels.[212]

- Cutting farm subsidies for livestock because these subsidies could discourage individuals shifting to a plant based diet (as those subsidies artificially lowers the price of meat and dairy products):[213]

- Rebalance the taxes and regulatory costs, which are currently higher for electricity than gas and thus discourage individuals from switching from gas boilers to heat pumps[213]

- Abolish Turkey's free coal for poor families[214] at such a program discourages people from switching to natural gas in cities.

- Redirecting the money which would have been spent as subsidies, together with any carbon tax, to form a carbon dividend in equal shares for everyone or for poor people to encourage individuals to take action as part of a just transition away from a high carbon lifestyle.[215]

However, sudden removal of a subsidy by governments not trusted to redirect it,[216] or without providing good alternatives for individuals, can lead to civil unrest. An example of this took place in 2019, when Ecuador removed its gasoline and diesel subsidies without providing enough electric buses to maintain service. The result was overnight fuel price hikes of 25–75 percent. The corresponding fare hikes for Ecuador's existing gas and diesel powered bus fleet were met with violent protests.[217]

Climate conversations

[edit]

"Discussing global warming leads to greater acceptance of climate science".[218] The Yale Climate Communication Program recommends initiating "climate conversations" with more moderate individuals.[219][43] Once personal climate impacts and core values are understood, it may become possible to open a discussion of potential climate solutions which are consistent with those core values.[219][220]

Carbon Conversations is a "psychosocial project that addresses the practicalities of carbon reduction while taking account of the complex emotions and social pressures that make this difficult".[221] It was cited in The Guardian newspaper as one of the 20 best ideas to tackle climate change.[222]

Other models and guides to having conversations regarding science, activism and further aspects of climate change have been developed by organisations such as Common Cause, the Australian Conservation Foundation, and the Public Interest Research Centre.[223]

Social contagion

[edit]Another opportunity for mitigation is through social contagion, where people in a network learn new behaviors, such as trying a plant-based diet or riding their bicycles to work instead of driving, and the new behaviors spread spontaneously through the group. For example, a 2020 Max Planck Institute study found that when meat-eaters are accompanied by vegetarians and have a choice of eating dishes with or without meat, they're more likely to choose a vegetarian dish, resulting in a reduction in the demand for meat. This probability increases as the number of vegetarians accompanying the meat eaters increases.[224]

Comparison of impacts of individual actions

[edit]

Public discourse on reducing one's carbon footprint overwhelmingly focuses on low-impact behaviors, and as of 2017, the mention of high-impact individual behaviors to impact climate was almost non-existent in mainstream media, government publications, K-12 school textbooks, etc.[167][174][needs update]

Media focus on low impact[226] rather than high impact behaviors is concerning for scientists. The most impactful actions for individuals may differ significantly from the popular advice for "greening" one's lifestyle. For instance, popular suggestions for individual actions include replacing a typical car with a hybrid, washing clothes in cold water, recycling, upgrading light bulbs which are all regarded as lower impact behaviors.

A few researchers have stated that some "recommended high-impact actions are more effective than many more commonly discussed options. For example, eating a plant-based diet saves eight times more emissions than upgrading light bulbs."[167][174] Recommended high-impact actions are around having fewer children,[183][227] living car-free, avoiding long-distance flights and eating a plant-based diet. However, other publications state that "population is actually irrelevant to solving the climate crisis".[228]

Other researchers say that decarbonization need not mean a more austere lifestyle, and that the individual actions with the most impact are to electrify households, with for example electric cars and heating.[229]

Scientists argue that piecemeal behavioral changes like re-using plastic bags are not a proportionate response to climate change. Though being beneficial, these debates would drive public focus away from the requirement for an energy system change of unprecedented scale to decarbonise rapidly. Moreover, policy measures such as targeted subsidies, eco-tariffs, effective sustainability certificates, legal product information requirements, CO2 pricing,[230] emissions allowances rationing,[231][232] budget-allocations/labelling,[231] targeted product-range exclusions, advertising bans, and feedback mechanisms are examples of measures that could have a more substantial positive impact on consumption behavior than changes exclusively carried out by consumers and could address social issues such as consumers' inhibitive constraints of budgets, awareness and time.[233]

Controversies around significance

[edit]It has been argued that climate change is a collective action problem, specifically a tragedy of the commons, which is a political[234] and not individual category of problem.[235]

Some commentators have argued that individual actions as consumers and "greening personal lives" are insignificant in comparison to collective action, especially actions that hold the fossil fuel corporations[clarification needed] accountable for producing 71% of carbon emissions since 1988.[6][236][237] The concept of a personal carbon footprint and calculating one's footprint was popularized by oil producer BP as "effective propaganda" as a way to shift their responsibility to "linguistically... remove itself as a contributor to the problem of climate change".[238] Others have shown that sometimes individual measures may effectively undermine political support for structural measures. In one example researchers found that "a green energy default nudge diminishes support for a carbon tax."[239]

Others say that individual action leads to collective action, and emphasize that "research on social behavior suggests lifestyle change can build momentum for systemic change."[7] Furthermore, if individuals shrink their consumption of fossil fuel products, fossil fuel corporations are incentivized to produce less, as the demand for their product would decrease.[240] In other words, each individual's consumption plays a role in the total supply of fossil fuels and emission of greenhouse gases.

According to a 2022 survey conducted by the European Investment Bank, climate change is the second most pressing issue confronting Europeans. Over three-quarters of respondents (72%) believe that their individual actions can make a difference in tackling the climate issue.[241]

Misleading information on individual actions

[edit]In many cases, media coverage of climate change reports only about the effects of climate change, such as extreme weather, but makes no mention of either individual or government actions which can be taken.

The suggestion that eating a plant-based diet requires a person to become strictly vegetarian is also misinformation.[242] A plant-based diet focuses on consuming foods primarily from plants but does not eliminate all animal products like a vegan diet does.[243]

Climate change education, which became mandatory in Italy in 2019,[244] is completely absent in some countries, or fails to provide information on action that individuals can take.

Climate inaction

[edit]It has been hypothesised many times that no matter how strong the climate knowledge provided by risk analysts, experts and scientists is, risk perception determines agents' ultimate response in terms of mitigation. However, recent literature reports conflicting evidence about the actual impact of risk perception on agents’ climate response. Rather, a no-direct perception-response link with the mediation and moderation of many other factors and a strong dependency on the context analysed is shown. Some moderation factors considered as such in the specialised literature include communication and social norms. Yet, conflicting evidence of the disparity between public communication about climate change and the lack of behavioural change has also been observed in the general public. Likewise, doubts are raised about the observance of social norms as an influencing predominant factor that affects action on climate change.[245] Disparate evidence also showed that even agents highly engaged in mitigation (engagement is a mediation factor) actions fail ultimately to respond.[246]

See also

[edit]- Climate movement – Social movement engaged in climate activism

- Environmental movement – Movement for addressing environmental issues

- Fossil fuel divestment – Divestment in companies that extract fossil fuels

- International Day of Climate Action – International environmental NGO

- List of climate activists – List of activists of have campaigned for climate change awareness

References

[edit]- ^ a b Crist, Eileen; Ripple, William J.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Rees, William E.; Wolf, Christopher (2022). "Scientists' warning on population" (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 845: 157166. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.84557166C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157166. PMID 35803428. S2CID 250387801.

While the speed at which climate disruption and biodiversity destruction are unfolding is alarming, the population factor continues to be ignored, sidestepped, or denied. This makes no sense—population is a primary variable underlying humanity's net consumption and waste output and thus a signicant driver of global change.

- ^ "Emissions inequality—a gulf between global rich and poor – Nicholas Beuret". Social Europe. 2019-04-10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- ^ Westlake, Steve (11 April 2019). "Climate change: yes, your individual action does make a difference". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2019-12-18. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Six key lifestyle changes can help avert the climate crisis, study finds". the Guardian. 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (31 May 2018). "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ a b Lukacs, Martin (July 17, 2017). "Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Sparkman, Leor Hackel, Gregg (2018-10-26). "Actually, Your Personal Choices Do Make a Difference in Climate Change". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vesely, Stepan; Masson, Torsten; Chokrai, Parissa; Becker, Anna M.; Fritsche, Immo; Klöckner, Christian A.; Tiberio, Lorenza; Carrus, Giuseppe; Panno, Angelo (2021). "Climate change action as a project of identity: Eight meta-analyses". Global Environmental Change. 70: 102322. Bibcode:2021GEC....7002322V. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102322. hdl:11590/396483.

- ^ a b "ExxonMobil wants you to feel responsible for climate change so it doesn't have to". www.vox.com. 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ a b Solnit, Rebecca (2021-08-23). "Big oil coined 'carbon footprints' to blame us for their greed. Keep them on the hook". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ a b "Emissions Gap Report 2020 / Executive Summary" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 2021. p. XV Fig. ES.8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2021.

- ^ a b Cozzi, Laura; Chen, Olivia; Kim, Hyeji (22 February 2023). "The world's top 1% of emitters produce over 1,000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1%". iea.org. International Energy Agency (IEA). Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. "Methodological note: ... The analysis accounts for energy-related CO2, and not other greenhouse gases, nor those related to land use and agriculture."

- ^ Stevens, Harry (1 March 2023). "The United States has caused the most global warming. When will China pass it?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023.

- ^ "In-depth Q&A: The IPCC's sixth assessment report on climate science". Carbon Brief. 2021-08-09. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "EDGAR - Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries, 2019 report - European Commission". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (2020-05-20). "Top 10 tips for combating climate change revealed". BBC. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ "Global CO2 emissions have been flat for a decade, new data reveals". Carbon Brief. 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ "COP26: Emissions of rich put climate goals at risk - study". BBC News. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "India urges G20 nations to bring down per capita emissions by '30". Hindustan Times. 2021-07-25. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "France: CO2 emissions 1970-2020". Statista. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "5 charts show how your household drives up global greenhouse gas emissions". PBS NewsHour. 2019-09-21. Archived from the original on 2020-01-15. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (2020-03-16). "The rich are to blame for climate change". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ^ "World's richest 10% produce half of carbon emissions while poorest 3.5 billion account for just a tenth". 2 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (April 13, 2021). "World's wealthiest 'at heart of climate problem'". BBC. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ IPCC (2022) Technical Summary. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

- ^ Patrick Devine-Wright, Julio Diaz-José, Frank Geels, Arnulf Grubler, Nadia Maïzi, Eric Masanet, Yacob Mulugetta, Chioma Daisy Onyige-Ebeniro, Patricia E. Perkins, Alessandro Sanches Pereira, Elke Ursula Weber (2022) Chapter 5: Demand, services and social aspects of mitigation in Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

- ^ "Reducing Your Carbon Footprint Can Be Good For Your Health" (PDF).

- ^ Akenji, Lewis; Lettenmeier, Michael; Koide, Ryu; Toivio, Viivi; Amellina, Aryanie (2019). 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and options for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Aalto University, and D-mat ltd. ISBN 978-4-88788-220-1.

- ^ "Emissions Gap Report 2020: chapter 6: Bridging the gap – the role of equitable low-carbon lifestyles" (PDF).

- ^ Heinonen, Jukka; Ottelin, Juudit; Ala-Mantila, Sanna; Wiedmann, Thomas; Clarke, Jack; Junnila, Seppo (2020-05-20). "Spatial consumption-based carbon footprint assessments - A review of recent developments in the field". Journal of Cleaner Production. 256: 120335. Bibcode:2020JCPro.25620335H. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120335. hdl:1959.4/102091. ISSN 0959-6526. S2CID 214015695.

- ^ Yang, Yong (2015-06-01). "Interactions between psychological and environmental characteristics and their impacts on walking". Journal of Transport & Health. 2 (2): 195–198. Bibcode:2015JTHea...2..195Y. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2014.11.003. ISSN 2214-1405. PMC 4480794. PMID 26120558.

- ^ Zhang, Yongping; Mi, Zhifu (2018-06-15). "Environmental benefits of bike sharing: A big data-based analysis". Applied Energy. 220: 296–301. Bibcode:2018ApEn..220..296Z. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.03.101. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 115512847.

- ^ Welle, Ben; Kustar, Anna; Tun, Thet Hein; Albuquerque, Cristina (2023-12-14). "Post-pandemic, Public Transport Needs to Get Back on Track to Meet Global Climate Goals".

- ^ Nesheli, Mahmood Mahmoodi; Ceder, Avishai (Avi); Ghavamirad, Farzan; Thacker, Scott (2017-03-01). "Environmental impacts of public transport systems using real-time control method". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 51: 216–226. Bibcode:2017TRPD...51..216N. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2016.12.006. ISSN 1361-9209.

- ^ a b c "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ fm (2022-02-02). "Cypriots prefer hybrid or electric cars". Financial Mirror. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Rahmani, Djamel; Loureiro, Maria L. (2018-03-21). "Why is the market for hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) moving slowly?". PLOS ONE. 13 (3): e0193777. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1393777R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193777. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5862411. PMID 29561860.

- ^ Handy, Susan; Weston, Lisa; Mokhtarian, Patricia L. (2005-02-01). "Driving by choice or necessity?". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 39 (2–3): 183–203. Bibcode:2005TRPA...39..183H. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.09.002. ISSN 0965-8564. S2CID 154344700.

- ^ a b Butt, Sarah; Shaw, Andrew (2009), "Pay More, Fly Less? Changing Attitudes to Air Travel", British Social Attitudes: The 25th Report, London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 129–154, doi:10.4135/9780857024350.n6, ISBN 978-1-84860-639-5, retrieved 2021-05-15

- ^ Mashayekh, Yeganeh; Jaramillo, Paulina; Samaras, Constantine; Hendrickson, Chris T.; Blackhurst, Michael; MacLean, Heather L.; Matthews, H. Scott (2012). "Potentials for Sustainable Transportation in Cities to Alleviate Climate Change Impacts". Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (5): 2529–2537. Bibcode:2012EnST...46.2529M. doi:10.1021/es203353q. PMID 22192244.

- ^ Hawkins, Troy R.; Gausen, Ola Moa; Strømman, Anders Hammer (2012-09-01). "Environmental impacts of hybrid and electric vehicles—a review". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 17 (8): 997–1014. Bibcode:2012IJLCA..17..997H. doi:10.1007/s11367-012-0440-9. ISSN 1614-7502. S2CID 109391241.

- ^ Shaheen, Susan; Cohen, Adam; Bayen, Alexandre (2018-10-22). "The Benefits of Carpooling". doi:10.7922/G2DZ06GF. S2CID 132842014.

- ^ a b c d Anair, Don, Jeremy Martin, Maria Cecilia Pinto de Moura, and Joshua Goldman. 2020. Ride-Hailing’s Climate Risks: Steering a Growing Industry toward a Clean Transportation Future. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

- ^ "Which form of transport has the smallest carbon footprint?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ Gössling, Stefan; Hanna, Paul; Higham, James; Cohen, Scott; Hopkins, Debbie (2019). "Can we fly less? Evaluating the 'necessity' of air travel". Journal of Air Transport Management. 81: 101722. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101722. S2CID 204435747.

- ^ a b Slotnick, David. "Airlines are working to cut down on emissions to secure their future business model, but the technology to make a real impact is still years away". Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ "Behaviour change, public engagement and Net Zero (Imperial College London)". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ a b "Seven charts that explain what net zero emissions means for the UK". www.newscientist.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Carbon offsetting flights. A dangerous distraction. Helping Dreamers Do". responsibletravel.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-18. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Air travel and climate change". David Suzuki Foundation. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Why Flying Carbon Class to COP26 Is More Expensive Than Taking the Train". Time. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ "Small cuts in air traffic would level off global heating caused by flying – study". the Guardian. 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ "Contrails: How tweaking flight plans can help the climate". BBC News. 2021-10-22. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 3: Europeans sceptical about successfully reducing carbon emissions by 2050, American and Chinese respondents more confident". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "Guide to Solar-Reflective Paints for Energy-Efficient Homes". Educational Community for Homeowners (ECHO). 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Using energy more efficiently". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ "Climate change: Four things you can do about your carbon footprint". 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ "The Outside/In[box]: What home heating system is best for the climate?". New Hampshire Public Radio. 2021-11-12. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- ^ "Behaviour change, public engagement and Net Zero (Imperial College London)". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ "What is green gas? – Ecotricity". www.ecotricity.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ "Distributed Solar Photovoltaics @ProjectDrawdown #ClimateSolutions". Project Drawdown. 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- ^ Arif, Mashail S. (2013). "Residential Solar Panels and Their Impact on the Reduction of Carbon Emissions" (PDF). Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Bank, European Investment (2023-06-05). The EIB Climate Survey: Government action, personal choices and the green transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5535-2.

- ^ Segran, Elizabeth (2021-08-10). "ACs are bulky, loud, and terrible for the environment. Is there a better version in our future?". Fast Company. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- ^ "The International EPD® System". www.environdec.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Brady, Jeff (2021-10-07). "We need to talk about your gas stove, your health and climate change". NPR.org. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ Oregon State University, OSU Extension Services (23 September 2022). "Through thoughtful practices, lawns can be climate-friendly". Ag - Community Horticulture/Landscape. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Regents of the University of California, Davis (April 10, 2023). "Carbon Sequestration". Climate Change Terms and Definitions. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Townsend-Small, Amy; Czimczik, Claudia (January 22, 2010). "Carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions in urban turf". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (2) – via University of California, Irvine.

- ^ a b c Son, Jiahn (May 12, 2020). "Lawn Maintenance and Climate Change". ClimateAction@princeton.edu. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Fountain, Henry; Kayson, Ronda (September 15, 2019). "One Thing You Can Do: Reduce Your Lawn". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-09-15. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Parzyszek, Paul (May 23, 2022). "Natural Lawns: A Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Alternative to Grass". Wiki Education. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Our Story. "Trees for the Future". Our Story. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Berners-Lee, Mike; Clark, Duncan (2010-11-25). "What's the carbon footprint of … a load of laundry?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "The Benefits of Using a Clothesline". Small Footprint Family™. 2009-08-10. Archived from the original on 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (2010-10-08). "High and dry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Hughes, Kathleen A. (2007-04-12). "To Fight Global Warming, Some Hang a Clothesline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Cotton, Lucy; Hayward, Adam S.; Lant, Neil J.; Blackburn, Richard S. (2020). "Improved garment longevity and reduced microfibre release are important sustainability benefits of laundering in colder and quicker washing machine cycles". Dyes and Pigments. 177: 108120. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.108120.

- ^ Hurst, Nathan. "What's the Environmental Footprint of a T-Shirt?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "The price of fast fashion". Nature Climate Change. 8 (1): 1. January 2018. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8....1.. doi:10.1038/s41558-017-0058-9. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ Feather, Katie. "How The Fashion Industry Is Responding To Climate Change". Science Friday. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Copyright © 2020 (27 February 2018). "Lessening the Harmful Environmental Effects of the Clothing Industry". Planet Aid, Inc. Archived from the original on 2019-02-04. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ro, Christine (March 27, 2020). "The hidden impact of your daily water use". BBC. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Law of Supply and Demand". Simplicable. 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ "U.S. dairy subsidies equal 73% of producer returns". realagriculture. 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ "Pros and Cons of US Government Subsidies". Pros and Cons. 2019-02-24. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ de Rugy, Veronique (2015-03-24). "Subsidies Are the Problem, Not the Solution, for Innovation in Energy". Mercatus. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 3: Europeans sceptical about successfully reducing carbon emissions by 2050, American and Chinese respondents more confident". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 1 of 3: Europeans sceptical about successfully reducing carbon emissions by 2050, American and Chinese respondents more confident". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 3 of 3: The economic and social impact of the green transition". EIB.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ Borunda, Alejandra (2019-06-11). "How can city dwellers help with climate change? Buy less stuff". National Geographic - Environment. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Alter, Lloyd (October 18, 2018). "How much does your household weigh?". TreeHugger. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Wharton, Rachel (June 21, 2023). "Worried About Your Gas Stove? Here's What to Do". Wirecutter.

- ^ Xanthos, Dirk; Walker, Tony R. (2017-05-15). "International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 118 (1–2): 17–26. Bibcode:2017MarPB.118...17X. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.02.048. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 28238328. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ Schnurr, Riley E. J.; Alboiu, Vanessa; Chaudhary, Meenakshi; Corbett, Roan A.; Quanz, Meaghan E.; Sankar, Karthikeshwar; Srain, Harveer S.; Thavarajah, Venukasan; Xanthos, Dirk; Walker, Tony R. (2018-12-01). "Reducing marine pollution from single-use plastics (SUPs): A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 137: 157–171. Bibcode:2018MarPB.137..157S. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.001. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 30503422. S2CID 54522420. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ ^ https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/30/dining/climate-change-food-eating-habits.html,%20https:/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/30/dining/climate-change-food-eating-habits.html, New York Times, dead link

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Smith, Pete; Haberl, Helmut; Montzka, Stephen A.; McAlpine, Clive; Boucher, Douglas H. (January 2014). "Ruminants, climate change and climate policy". Nature Climate Change. 4 (1): 2–5. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4....2R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2081. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ a b "Emissions from food". www.carbonindependent.org. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "COP26: Emissions of rich put climate goals at risk - study". BBC News. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Food Loss and Waste". www.usda.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "Reduced Food Waste @ProjectDrawdown #ClimateSolutions". Project Drawdown. 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Zhu, Jingyu; Luo, Zhenyi; Sun, Tingting; Li, Wenxuan; Zhou, Wei; Wang, Xiaonan; Fei, Xunchang; Tong, Huanhuan; Yin, Ke (March 2023). "Cradle-to-grave emissions from food loss and waste represent half of total greenhouse gas emissions from food systems". Nature Food. 4 (3): 247–256. doi:10.1038/s43016-023-00710-3. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37118273. S2CID 257512907.

- ^ "Why should we care about food waste?". www.usda.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ says, Rajesh Kr. "Food waste: digesting the impact on climate". New Food Magazine. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Li, Mengyu; Jia, Nanfei; Lenzen, Manfred; Malik, Arunima; Wei, Liyuan; Jin, Yutong; Raubenheimer, David (June 2022). "Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions". Nature Food. 3 (6): 445–453. doi:10.1038/s43016-022-00531-w. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37118044. S2CID 249916086.

- ^ http://www.foodcoldchain.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Reducing-GHG-Emissions-with-the-Food-Cold-Chain-NOV2015.pdf, Assessing the potential of the cold chain sector to reduce GHG emissions through food loss and waste reduction, Page 16, Table 4.

- ^ "REDUCE THE CLIMATE IMPACT OF PACKAGING | Why Commit To Reducing The Climate Impact Of Packaging?". The Climate Collaborative. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "The Environmental Impact of Food Packaging". FoodPrint. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (2019-06-18). "Japan wraps everything in plastic. Now it wants to fight against plastic pollution". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ "The over-packaging problem in Japan". Univibes. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/world/all-the-plastic-thats-left-after-making-dinner-in-japan/2019/06/18/86b97234-eb7b-4305-a9c2-57e6a0d33675_video.html All the plastic that's left after making dinner in Japan, June 18, 2019.

- ^ Joe, Melinda (25 August 2022). "Quitting single-use plastic in Japan". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Moskin, Julia; Plumer, Brad; Lieberman, Rebecca; Weingart, Eden; Popovich, Nadja (2019-04-30). "Your Questions About Food and Climate Change, Answered (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Smith, Pete; et al. (2013). "Ruminants, climate change and climate policy" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 4 (1): 2–5. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4....2R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2081.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R (November 5, 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278.

- ^ "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". the Guardian. 2018-05-31. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Briggs, Nassos Stylianou, Clara Guibourg and Helen (2018-12-13). "Climate change food calculator: What's your diet's carbon footprint?". Archived from the original on 2019-10-12. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gallagher, James (2019-01-17). "Meat, veg, nuts - a diet designed to feed 10bn". Archived from the original on 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- ^ "Healthy diet". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (August 8, 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ Grossi, Giampiero; Goglio, Pietro; Vitali, Andrea; Williams, Adrian G. (2019). "Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies". Animal Frontiers. 9 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1093/af/vfy034. PMC 7015462. PMID 32071797. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Plant-Rich Diet". Drawdown. 2023-11-17. Archived from the original on 2019-11-20. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Chodosh, Sara (March 21, 2018). "One-fifth of Americans are responsible for half the country's food-based emissions". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Heller, Martin C.; Willits-Smith, Amelia; Meyer, Robert; Keoleian, Gregory A.; Rose, Donald (March 2018). "Greenhouse gas emissions and energy use associated with production of individual self-selected US diets". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (4): 044004. Bibcode:2018ERL....13d4004H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aab0ac. ISSN 1748-9326. PMC 5964346. PMID 29853988.

- ^ "How plant-based diets not only reduce our carbon footprint, but also increase carbon capture". Leiden University. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Sun, Zhongxiao; Scherer, Laura; Tukker, Arnold; Spawn-Lee, Seth A.; Bruckner, Martin; Gibbs, Holly K.; Behrens, Paul (January 2022). "Dietary change in high-income nations alone can lead to substantial double climate dividend". Nature Food. 3 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00431-5. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37118487. S2CID 245867412.

- ^ "2022-2023 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 2: Majority of young Europeans say the climate impact of prospective employers is an important factor when job hunting". EIB.org. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (20 July 2023). "Vegan diet massively cuts environmental damage, study shows". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Rosado, Pablo; Roser, Max (2022-12-02). "Environmental Impacts of Food Production". Our World in Data.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Rosado, Pablo; Roser, Max (2022-12-02). "Less meat is nearly always better than sustainable meat, to reduce your carbon footprint". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b c d Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. (June 2018). "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers". Science. 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216. PMID 29853680.

- ^ "What foods create the most & least greenhouse gas emissions?". Center for Science in the Public Interest. January 2025. Retrieved 2025-01-29.

- ^ Bulson, Erin E.; Kontar, Wissam; Ahn, Soyoung; Hicks, Andrea (2024-05-22). "Reduced travel emissions through a carbon calculator with accessible environmental data: a case study in Madison, Wisconsin". npj Sustainable Mobility and Transport. 1 (1): 3. Bibcode:2024npjSM...1....3B. doi:10.1038/s44333-024-00003-7. ISSN 3004-8664.

- ^ Malecek, Adam. "A more digestible CO2 calculator swaps cheeseburgers for carbon". College of Engineering - University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved 2025-01-29.

- ^ "The Cheeseburger Footprint". www.openthefuture.com. Retrieved 2025-01-29.

- ^ "People, Planet, or Profit: alcohol's impact on a sustainable future" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Cook, Megan; Critchlow, Nathan; O’Donnell, Rachel; MacLean, Sarah (2024-02-01). "Alcohol's contribution to climate change and other environmental degradation: a call for research". Health Promotion International. 39 (1): daae004. doi:10.1093/heapro/daae004. ISSN 0957-4824. PMC 10836053. PMID 38305639.

- ^ Carruthers, Nicola (2021-10-26). "Packaging innovation: making spirits more sustainable". The Spirits Business. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "The Alcohol We Drink and Its Contribution to the UK's Greenhouse Gas Emissions" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Vegan, Celebr8 (2023-04-29). "Alcohol Production and Green House Gas Emissions". Medium. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rail, Evan (2024-06-05). "The Drinks Industry Has a Huge Carbon Footprint. There Are Solutions". VinePair. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "Alcohol's Impact On the Environment | Blueland". Blueland. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "Sustainable Brew: How the Alcohol Industry Impacts Climate Change | Museum of Science". www.mos.org. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ lesliebarland (2024-01-25). "Alcohol & Climate". Bridging the Gap. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "Sustainability and Environment in the Alcohol Industry | Moving Spirits". 2023-06-14. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ Kilgore, Georgette (2023-01-25). "Carbon Footprint of Wine (Bottle) vs Beer and 13 More Liquor Types". 8 Billion Trees: Carbon Offset Projects & Ecological Footprint Calculators. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "How green is your beer? | Imperial News | Imperial College London". Imperial News. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "Food Product Environmental Footprint Literature Summary: Beer" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-02-05.

- ^ Cimini, Alessio; Moresi, Mauro (2016-01-20). "Carbon footprint of a pale lager packed in different formats: assessment and sensitivity analysis based on transparent data". Journal of Cleaner Production. 112: 4196–4213. Bibcode:2016JCPro.112.4196C. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.063. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ "The Oxford Companion to Beer Definition of light beer". Craft Beer & Brewing. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ "The Step-by-Step Process of Non-Alcoholic Beer Brewing". CRAFTMASTER STAINLESS. 2023-12-18. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ Sohrabvandi, S.; Mousavi, S.M.; Razavi, S.H.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Rezaei, K. (2010-09-30). "Alcohol-free Beer: Methods of Production, Sensorial Defects, and Healthful Effects". Food Reviews International. 26 (4): 335–352. doi:10.1080/87559129.2010.496022. ISSN 8755-9129.

- ^ "Alcohol Free Beer & Sustainability". LightDrinks. 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

- ^ Yabaci Karaoglan, Selin; Jung, Rudolf; Gauthier, Matthew; Kinčl, Tomáš; Dostálek, Pavel (June 2022). "Maltose-Negative Yeast in Non-Alcoholic and Low-Alcoholic Beer Production". Fermentation. 8 (6): 273. doi:10.3390/fermentation8060273. ISSN 2311-5637.

- ^ "Reducing Carbon Footprint and Water Consumption in Alcohol-Free Beer Production: Comparing Maltose- and Crabtree-Negative Yeast to Thermal Dealcoholization" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-02-05.