Inglewood, Edmonton

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

Inglewood | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood | |

127 Street in Inglewood | |

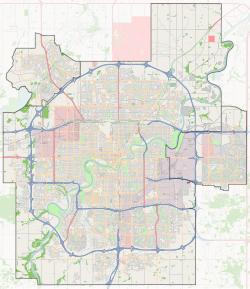

Location of Inglewood in Edmonton | |

| Coordinates: 53°33′N 113°31′W / 53.550°N 113.517°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| City | Edmonton |

| Quadrant[1] | NW |

| Ward[1] | Anirniq |

| Sector[2] | Mature area |

| Government | |

| • Administrative body | Edmonton City Council |

| • Councillor | Erin Rutherford |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.65 km2 (0.64 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 672 m (2,205 ft) |

| Population (2012)[5] | |

• Total | 6,310 |

| • Density | 3,824.2/km2 (9,905/sq mi) |

| • Change (2009–12) | |

| • Dwellings | 4,140 |

Inglewood is a residential neighbourhood in north west Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Between 1946 and 1996, Edmonton's Charles Camsell Hospital was located in the neighbourhood. The hospital was named after Canadian geologist, map maker and Commissioner of the Northwest Territories, Charles Camsell.

The neighbourhood is bounded on the north by 118 Avenue, on the south by 111 Avenue, on the west by Groat Road, and on the east by a former Canadian National Railway right of way.

The community is represented by the Inglewood Community League, established in 1950, which maintains a community hall located at 125 Street and 116 Avenue.[6][7]

History

[edit]As of 1882, portions of the present neighbourhood were owned by an employee of the Hudson's Bay fur trading company, operating a few kilometres away at Fort Edmonton.[8] Located along the original St. Albert Trail, connecting the settlements of St. Albert and Edmonton, the area was used by Métis and First Nations peoples for their campsites when they came to do business in Edmonton.[8]

The majority of Inglewood was added to Edmonton during an annexation in 1904, with the portion west of 127 Street added in a 1908 annexation.[9]

Demographics

[edit]In the City of Edmonton's 2012 municipal census, Inglewood had a population of 6,310 living in 4,140 dwellings,[5] a -1.3% change from its 2009 population of 6,394.[10] With a land area of 1.65 km2 (0.64 sq mi),[4] it had a population density of 3,824.2/km2 (9,905/sq mi) in 2012.[4][5]

Residential development

[edit]

Residential development in Inglewood began prior to the end of World War II, when roughly one residence in eight was constructed. However, most of the existing residences (78% of the total) were built during the next 35 years. Residential construction tapered off during the 1980s and was substantially complete by 1990.[11]

According to the 2005 municipal census, the most common type of residence in the neighbourhood is the rented apartment; these constitute seven out of ten (69%) of the residences. Most apartments are in low-rise buildings with fewer than five stories. Single-family dwellings account for only one in four (25%) of all residences. Duplexes account for the remaining 6%.[12] Three out of four (76%) of residences are rented with the remainder being owner occupied.[13]

Population mobility

[edit]The population in Inglewood is highly mobile. According to the 2005 municipal census, one in four (25.4%) residents had moved within the preceding 12 months. Another one in four (26.8%) had moved within the previous one to three years. Only one in three (33%) of residents had lived at the same address for five years or more.[14]

Schools

[edit]

There are four schools in the neighbourhood.

- Edmonton Public School System

- Inglewood Elementary School

- Westmount Junior High School

- Muslim Association of Canada

- MAC Islamic School

- Other

- Indigo Sudbury Campus

Charles Camsell Hospital

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

In 1946, Lord Alexander, then Governor General of Canada, opened The Charles Camsell tuberculosis hospital in Edmonton, in a former Jesuit college built in 1910 and later occupied by the Canadian Army during World War II as a staff and administration building and medical corps hospital during construction of the Alaska Highway 1942-1945. [15] This hospital, which was located in the Inglewood area, was named after Charles Camsell (1876–1958), who was at the time Commissioner of the Northwest Territories as well as a geologist and map-maker dedicated to the exploration of Canada's North.[16] It was operated by the Indian Health Service of the Department of National Health and Welfare and later transferred to the Department of Indian Affairs.

In 1964 the Department of Indian Affairs established the Northern Medical Research Unit under the direction of Otto Schaefer. The Unit was created to address the overwhelming response to a 1959 paper about Arctic health Schaefer published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. The paper was a summary of his medical and personal observations of the changes to Inuit lifestyle with the coming of the Distant Early Warning Line (DEW Line) and increasing southern influence. For the next two decades Schaefer and his staff travelled the Arctic collecting medical information, administering vaccinations to remote camps, and seeing to the general health care of Inuit and First Nations groups in the Arctic. The Unit spent two months a year in the Arctic, as well as occasional emergency trips, and at the Charles Camsell Hospital analysing the data collected and seeing to patients. The conclusions of this research indicated changes to traditional life by increased influence of southern non-indigenous culture on lifestyle, diet, and social structure had enormous negative health effects. Schaefer became a vocal advocate for a return to traditional lifestyles as a means of countering declining health and better treating medical problems in the Arctic and in hospitals like the Charles Camsell.

Between 1945 and 1967, the hospital operated an occupational therapy program for indigenous patients. In 1990, the hospital donated a collection of over 400 arts and crafts items made by patients in the program to the Royal Alberta Museum.[17] From the 60s to the 80s, the hospital was used in Albertan Eugenics programs in order to sterilize indigenous peoples.[18] It was mentioned in multiple class action lawsuits against both the province and Canada. The hospital was also a place where medical testing was performed on natives, and from where indigenous children were abducted to be adopted by non-indigenous.

A new 385-bed Charles Camsell Hospital was completed in 1966-1967 at 128th Street and 114th Avenue in Edmonton, Alberta. The hospital was closed and abandoned in 1996, condemned due in part to asbestos, and in part due to its history in Canadian genocide and eugenics.[18] The hospital had been owned by a number of people over the years with development in mind, and some construction and gutting of the floors has taken place, but nothing substantial has been done. No actual development has been finished. The movie White Coats, released in 2004, was filmed in this hospital. In 2006, there was a fire in the building caused by a demolition crew, but firefighters had to fight the fire from the outside of the building since barbed wire had been wrapped around the railings of staircases, in a poor attempt to keep the homeless population out of the building. As of 2017, the building and grounds sit empty, and are surrounded by a fence. A private security service actively patrols the facility, and hefty fines are given to trespassers. In 2018, they’ve started to frame in the individual condominiums in the tower.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "City of Edmonton Wards & Standard Neighbourhoods" (PDF). City of Edmonton. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "Edmonton Developing and Planned Neighbourhoods, 2011" (PDF). City of Edmonton. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "City Councillors". City of Edmonton. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Neighbourhoods (data plus kml file)". City of Edmonton. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Municipal Census Results – Edmonton 2012 Census". City of Edmonton. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ "Inglewood Community League". Inglewood Community League. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Kuban, Ron (2005). Edmonton's Urban Villages: The Community League Movement. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 9781459303249.

- ^ a b "Inglewood History". Inglewood Community League of Edmonton. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ^ History of Annexations (PDF) (Map). City of Edmonton, Urban Planning and Environment. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ^ "2009 Municipal Census Results". City of Edmonton. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ 2001 Federal Census - Period of Construction - Occupied Private Dwellings

- ^ Duplexes include triplexes and quadruplexes.

- ^ 2005 Municipal Census - Dwelling Unit by Structure Type and Ownership

- ^ 2005 Municipal Census - Length of Residence

- ^ The Norther, July 29, 1965

- ^ Trailblazer - Charles Camsell: Natural Resources Canada Archived 2010-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Royal Alberta Museum: Museum Shop: Catalogues Archived 2007-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Charles Camsell Indian Hospital". The Eugenics Archives. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

KSF

KSF