Innocents and Others

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 4 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 4 min

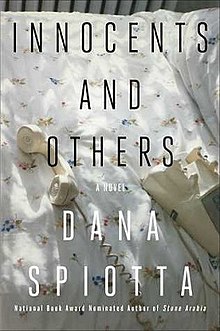

First edition | |

| Author | Dana Spiotta |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Scribner |

Publication date | March 8, 2016 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 289 pp |

| ISBN | 978-1-5098-3914-8 |

| OCLC | 1026680855 |

Innocents and Others is an American novel by Dana Spiotta, first published by Scribner in 2016. It follows the friendship of two American filmmakers, Meadow Mori and Carrie Wexler, who grow up together and remain friends as their careers rise.

Plot

[edit]In the 1980s, teenage Meadow Mori writes an experimental essay during which she watches City Lights twenty times in a row; she does this because her favourite filmmaker claimed everything he learned about film he learned from watching this film 20 times. After her project is done, she sends a copy to the filmmaker, who invites her to lunch. The two begin an affair, and Meadow defers university to live with him. He warns Meadow that he is ill and urges her to use his fame and the scandal of their relationship to acquire fame and fortune. However, when he dies Meadow only takes a few tokens and prefers to find her own path to success, never publishing the love letters he wrote her. The story is part of an online essay Meadow wrote, and comments reveal that the man in question is thought to be Orson Welles.

Meadow eventually heads to Gloversville where she makes experimental films. Her first documentary feature is an interview with her younger lover, whom she records as he is increasingly drunk, based on Portrait of Jason. The film gains enough acclaim that Meadow is able to make a second film, Kent State: Recovered, about student protests over the Vietnam war. She is nominated for an Oscar for her film.

Carrie makes a well-received student short and is able to use that to get enough funding to make her first feature film, which Meadow finds conventional and uninteresting.

Searching for a new subject, Meadow learns of "Nicole", a woman who seduced powerful Hollywood men a few years earlier by cold calling them and talking to them over the phone. She manages to track down Nicole, who is actually a woman nicknamed "Jelly", who is partially sighted, somewhat overweight, and was middle aged at the time she made these calls, inspired by her then boyfriend who was involved in phone phreaking. Jelly is reluctant to be interviewed for Meadow's film until she learns that Jack Cusano, a composer with whom she fell in love, has agreed to be interviewed.

Carrie watches the film, in which Jack finally meets "Nicole" and is disgusted with her. Jelly accuses Meadow of using her pain for her own selfish purposes. Though Meadow apologizes to Jelly, she is haunted by her words.

Meadow decides to make a documentary on Sarah Mills, a woman in prison for arson who is accused of murdering her husband and child. Though Sarah says the fire was an accident, she admits that she had the opportunity to save her daughter and deliberately chose not to. Meadow destroys the footage.

Later, Meadow is also involved in a car accident. She takes stock of her life and reflects on the cruel person she has become. She abandons filmmaking and decides to dissolve most of her trust fund, living a simple, pared- down life. She eventually takes up teaching.

Jack Cusano discovers that he is dying and, tired of the people in his life who only want to talk about his impending death, reconnects with Jelly. He never tells her he is dying.

Things continue to go well with Carrie, who becomes a popular director of commercial films and always credits Meadow with her success. She suggests that Meadow's essay on her love affair with "Orson Welles" was complete fiction. On Boxing Day, after being stood up by her son, Carrie decides to reunite with Meadow, and they watch Daisies together in the theatre.

Characters

[edit]- Meadow Mori, an L.A.-born wealthy filmmaker who is interested in documentaries and experimental films

- Carrie Wexler, an L.A.-born woman who is haunted by her childhood plumpness. Carrie grows up middle class in an upper-class neighborhood and goes on to direct successful comedies.

Reception

[edit]The novel was well received. The New York Times praised it as "a combo-deal of a novel that mixes the silliness of a popcorn romp with the intellectual seriousness of a one-camera talking-head commentary."[1] The Irish Times called it "an affectionate homage to the cinematic form itself."[2] The Guardian enjoyed how Spiotta's writing "resists easy depiction at every turn."[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Cohen, Joshua. "'Innocents and Others,' by Dana Spiotta". Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Barekat, Houman. "Innocents and Others review: silver screen savers". Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Gunn, Kirsty. "Innocents and Others by Dana Spiotta review – an adventure in film". Retrieved 23 July 2018.

KSF

KSF