Intestate succession in South African law

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2022) |

Intestate succession in South African law takes place whenever the deceased leaves property which has not been disposed of by valid testamentary instrument. In other words, the law of intestate succession applies only:

- when the testator has left no valid will or testamentary disposition contained in a valid pactum successorium (e.g., antenuptial contract, gift mortis causa); or

- when he leaves a will which fails for some or other reason.

Intestacy may be total (applying to the whole of the assets left by the deceased) or partial (applying to a portion only of his assets), for the deceased may die partly testate and partly intestate: for example, if the deceased bequeaths his car to his son but does not mention the rest of his estate.[1]

Intestacy is total when none of the assets are disposed of by a valid will: for example, where there is no will at all, or only a will which is void, or which has been revoked. Intestacy is partial when the deceased has left a valid will which, however, does not dispose of all his assets; in this event there is an intestacy as to the undisposed residue. This may happen in many circumstances: for example,

- where the will does not appoint an heir at all, but appoints only legatees, and a residue is left over after the liabilities and the legacies have been satisfied;

- where the appointed heir(s) fail to succeed;

- where an heir is appointed to a fractional portion of the estate only, and there is no other disposition of property;

- where heirs have been appointed, each to a fractional portion of the estate, and the disposition to one of them is a nullity, or one of them fails to succeed to his share.

Furthermore, intestacy can occur if certain conditions in an otherwise valid will are not fulfilled, or if benefits have been repudiated and no provision has been made for substitution, and accrual cannot take place.

History and sources

[edit]The law of intestacy was virtually codified by the Intestate Succession Act, 1987,[2] which came into force on 18 March 1988. Before that, the South African system of intestate succession had to be construed from a variety of common-law and statutory rules. The law of intestate succession is rooted in the legislation of the States of Holland: the Political Ordinance of 1 April 1580, as clarified and amended by the Interpretation Ordinance of 13 May 1594 and Section 3 of the Placaat of 18 December 1599.

In 1621 the Heeren XVII of the Dutch East India Company instructed the government of the Dutch East Indies to enforce these enactments, and the States-General decreed them to be in force in Cape Colony by the Octrooi of 10 January 1661, which was confirmed by Governor Pasques de Chavonnes on 19 June 1714.

The main common-law principles of intestacy were derived from a combination of two systems, somewhat in conflict, which prevailed prior to 1580 in the Netherlands: the aasdomsrecht, the law of North Holland and Friesland, which meant "the next in blood inherits the properties", and the schependomsrecht, the law of South Holland and Zeeland, which meant "the properties return to the line whence they came".[3] Under both systems, the property of an intestate person went to the deceased's blood relations only: in the first place, to his descendants; failing them, to his ascendants and collaterals. There were several important differences in the manner of devolution.

The 1580 Ordinance adopted the schependomsrecht distribution per stirpes, restricting it in the case of collaterals to the fourth degree inclusive. Finally, the 1599 Placaat compromised between the two systems with respect to distribution, and gave one half of the estate to the surviving parent, and the other half to the descendants of the deceased parent.[4][5]

The above laws conferred a right of succession on intestacy on the deceased's blood relations, but none on a surviving spouse or an adopted child, and furthermore restricted the intestate succession rights of the extra-marital child. Because marriage in community of property was the norm, such a spouse ipso facto took half of the joint estate.

Initially, the word spouse in the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 was restrictively interpreted to mean only those spouses who had contracted a marriage in terms of the Marriage Act, 1961.[6] This interpretation has since been extended by case law, in recognition of the modern perception that there is a need to protect the interests of surviving spouses. The common law, as derived from the two different systems that applied in Holland, has been adapted on numerous occasions by legislation. The most important such legislation was probably the Succession Act, 1934,[7] in terms of which the surviving spouse, whether married in or out of community, was granted a right to a share in the intestate estate of the deceased spouse.

The Intestate Succession Act, 1987[2] instituted a much simpler system of intestate succession, revoking common-law rules and all statutory adaptations in their entirety. The Intestate Succession Act, 1987, together with the Children's Act, 2005, extended the categories of persons who may be heirs who take in intestacy. For example, all natural persons, irrespective of whether they are adopted or extra-marital, or conceived by artificial insemination, or born as a result of a surrogacy arrangement, nowadays have the capacity to inherit.

The Intestate Succession Act, 1987 applies, except as explained below, in all cases where a person dies wholly or partially intestate after 18 March 1988. Under the Act, the surviving spouse and the adopted child are heirs of the deceased. The historical discrimination visited on extra-marital children has disappeared. The position of adopted children is now dealt with in the Child Care Act, 1983.[8]

Until recently, the application of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 was regulated on a racial basis. Certain intestate estates of African people were distributed according to the "official customary law," as entrenched in the Black Administration Act, 1927 and its regulations, while the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 applied to the rest of the population. The Black Administration Act, 1927, and the Regulations passed thereunder, provided that the estates of black people who died without leaving a valid will sometimes devolved according to "Black law and custom." This meant, inter alia, that the reforms introduced by the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 did not apply to spouses married in terms of African customary law. As far as children were concerned, the parallel system of African customary law of succession perpetuated discrimination against adopted, extra marital and even female children.

This racial disparity in the treatment of spouses and children disappeared when the Constitutional Court, in Bhe v Magistrate, Khayelitsha, extended the provisions of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 retrospectively, as from April 27, 1994, to all intestate heirs, irrespective of race.

While the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 is important, one cannot discount case law when determining the rules of intestate succession. If and when the RCLSA is promulgated into law, it, too, will be relevant for determining South Africa's intestate-succession laws.

Computation of kinship

[edit]Blood relations

[edit]- Descendants are persons who descend directly from another person, such as children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, etc.

- Ancestors are persons from whom the person is directly descended, like parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.

- Ascendants are ancestors and collaterals.

- Collaterals are relatives descended from the deceased's ancestors but not in the direct line of descent, i.e., neither ancestors nor descendants—such as siblings, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, etc.

- Collaterals can be full- or half-blooded. A full-blood collateral has two ancestors in common with a person; a half-blood collateral has only one. A sister, therefore, is a full-blood collateral—she has both parents in common with her sibling—but a half-sister is only a half-blood collateral, since she has only one parent in common. If, in other words, Boucher and Cronje are descendants of Abel—that is, if Abel is an ancestor of Boucher and Cronje—Boucher and Cronje are full-blood collaterals.

- Collaterals can be first-, second- or third-line. First-line collaterals are the descendants of the deceased's parents, i.e., the deceased's siblings and nieces and nephews. Second-line collaterals are the issue of the grandparents not including the parents, which includes uncles and aunts, and first cousins. Likewise, third-line collaterals are the issue of great-grandparents not including grandparents and parents, and so on.

Distribution scheme

[edit]

South Africa uses the Roman-Dutch parentelic system to reckon kinship and determine distribution in intestacy. The term parentela refers to a particular parental group and its descendants:

- First parentela consists of the deceased and his descendants.

- Second parentela consists of the deceased's parents and their descendants (first-line collaterals).

- Third parentela consists of the deceased's grandparents and their descendants (second-line collaterals).

- Fourth parentela consists of great-grandparents and their descendants (third-line collaterals).

And so the parentelae go on. Essentially, the lowest parentela wins and takes the entire estate, and parentelic heads trump others within the same parentela.

A stirp may be translated literally as a branch. In the present context, therefore, it includes the surviving child of a deceased, as well as a predeceased child survived by descendants.

When determining how many stirpes there are, one should pay attention to the immediate descendants of the deceased and then see if they are alive or if their descendants are alive.

Representation arises when an heir cannot, or does not wish to, inherit from the deceased. In this case, the descendants of the heir may represent the heir to inherit.

Effect of marital regimes

[edit]If the deceased is married at the time of his death, the property system that applies to his marriage is of utmost importance since it affects the distribution of the deceased's estate. In terms of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 1998 and the Matrimonial Property Act, 1984, the first marriage of a male with more than one wife is always considered to be in community of property. If a second marriage is entered into, the parties must enter into an antenuptial contract, which will regulate the distribution of the estate.

Essentially, there are four forms of marital regimes recognised by the courts:

- community of property (Afrik gemeenskap van goed);

- community of profit and loss (Afrik gemeenskap van wins en verlies);

- separation of property (Afrik skeiding van goed); and

- the accrual system (Afrik aanwasbedeling).

With regard to marriages in community of property or in community of profit and loss, the surviving spouse automatically succeeds to half of the joint estate (communio bonorum); the remaining half devolves according to the rules of intestate succession.

With regard to marriages in separation of property,[9] the entire estate devolves according to the rules of intestate succession.

With regard to the accrual system,[10] where one spouse's estate shows no or lesser accrual than that of the other spouse, the lesser-accruing spouse has a claim for an amount equal to half of the difference between the two net accrued estates. The equalization payment must be dealt with first as a claim against or in favour of the estate. The balance thereafter must devolve according to rules of intestate succession.

If a husband has an estate of R100,000 at the start of his marriage, and R200,000 at the end of the marriage, R100,000 will have accrued. If his wife, at the start of her marriage, has an estate worth R50,000, and at the end of the marriage worth R100,000, the amount accrued will be R50,000. If the husband dies, the difference in the accrual of both estates is R50,000; therefore the wife has a claim for half of the accrued amount: R25,000. Thereafter the remainder of the estate will devolve in terms of the rules of intestate succession.

Vesting of intestate-succession rights

[edit]The question of who in fact the heirs are is normally determined as at the date of the death of the deceased. Where, however, the deceased leaves a valid will which takes effect on his death, but subsequently fails, either wholly or in part, the intestate heirs are determined as at the date on which it first became certain that the will had failed.

Order of succession on intestacy

[edit]Section 1(1)(a) to (f) of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 contains the provisions in terms of which a person's estate is to be divided. In terms of this section, there are ten categories which indicate who will inherit. Section 1(2) to (7) contains certain related provisions.

Spouse only, no descendants

[edit]Where the deceased is survived by a spouse, but not by a descendant, the spouse inherits the intestate estate. "Spouse" includes

- a person married to the deceased in accordance with Muslim rites;

- a person married to the deceased in terms of African Customary Law; and

- a partner in a permanent same-sex life partnership in which the partners have undertaken reciprocal duties of support.

No spouse and only descendants

[edit]

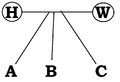

Where the deceased is survived by a descendant, but not by a spouse, the descendant inherits the intestate estate. The estate is divided into as many equal portions as there are surviving children and deceased children who leave descendants. Each surviving child takes one share, termed a "child’s share," and the share of each deceased child is divided equally among his surviving children and each group of descendants of a deceased child. This process is known as representation per stirpes; it continues ad infinitum.

An adopted child is deemed, for all purposes, to be the legitimate child of its adoptive parent. An order of adoption terminates all rights and obligations existing between the child and its natural parents (and their relatives). It follows that an adopted child inherits upon the intestacy of its adoptive parents and their relatives, but not upon the intestacy of its natural parents and their relatives.

Under Roman-Dutch law, an illegitimate or extra-marital child inherited upon the intestacy of its mother, but not of its father. This limitation on the capacity of the extra-marital child to inherit on intestacy has been swept away by the Intestate Succession Act, which provides that, in general, illegitimacy shall not affect the capacity of one blood relation to inherit the intestate estate of another blood relation. Illegitimacy arising from incest, too, no longer presents a problem. Furthermore, as noted earlier, the tenuous position of extra-marital children under African customary law of succession, too, has been removed by making the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 applicable to all children.

Spouse and descendants

[edit]

Where the deceased is survived by one spouse, as well as by a descendant, the surviving spouse inherits whichever is the greater of

- a child's share; and

- an amount fixed from time to time by the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development (presently R250,000).

The descendant or descendants inherit the residue (if any) of the intestate estate.

To calculate a child's share, the estate is divided into as many children's shares as stated above, plus an additional share, which the surviving spouse takes.

Where the deceased is survived by more than one spouse, a child's share in relation to the intestate estate of the deceased is calculated by dividing the monetary value of the estate by a number equal to the number of children of the deceased who have either survived or predeceased the deceased, but who are survived by their descendants, plus the number of spouses who have survived the deceased. Each surviving spouse inherits whichever is the greater of

- a child's share;

- an amount fixed from time to time by the Minister (presently R250 000).

The descendant or descendants inherit the residue (if any) of the intestate estate. Where the assets of the deceased are not sufficient to provide for each spouse with the amount fixed by the Minister, the estate is divided between the surviving spouses.

The share inherited by a surviving spouse is unaffected by any amount to which he or she might be entitled in terms of the matrimonial-property laws.

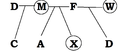

No spouse, no descendants; both parents survive the deceased

[edit]Where the deceased leaves neither a spouse nor a descendant, but is survived

- by both his parents, they inherit the intestate estate in equal shares; or

- by one of his parents, the surviving parent inherits one half of the intestate estate and the descendants of the deceased parent the other half, unless there are no such descendants, in which case the surviving parent inherits the entire estate.

In relation to the descendants of a parent of the deceased, division of the estate takes place per stirpes. Representation is allowed ad infinitum.

No spouse, no descendants; only one parent survives; deceased parent leaves descendants

[edit]In this case, the surviving parent will inherit half of the estate, and the descendants of the deceased parent will inherit the residue per stirpes by representation.

In this case, the surviving parent is the sole heir.

No spouse, no descendants, no parents; both parents leave descendants

[edit]

Where the deceased is not survived by a spouse or descendant or parent, but is survived by descendants of his parents (by a brother or sister, for example, whether of the full or half blood), the intestate estate is divided into halves, one half going to the descendants of the deceased father by representation, the other half to the descendants of the deceased mother. The full brothers and sisters of the deceased consequently take a share in both halves of the estate, while the half-brothers and -sisters take a share in one half only of the estate. If, however, all the surviving descendants are related to the deceased through one parent alone, such descendants inherit the entire estate. Thus, for example, if there are no full brothers or sisters, but merely a half-brother of the deceased on his mother's side, the half-brother will take the whole estate to the exclusion of more remote relatives such as grandparents, uncles or aunts.

No spouse, no descendants, no parents; one parent leaves descendants

[edit]

In this case, the descendants of the parents will inherit the entire estate in equal shares. The descendants inherit per stirpes by representation.

No spouse, no descendants, no parents, no descendants of the parents

[edit]

Where the deceased is not survived by a spouse, descendant, parent, or a descendant of a parent, the other blood relations of the deceased who are related to him nearest in degree inherit the estate in equal shares (per capita). The degree of relationship between the parties is,

- in the direct line, the number of generations between the deceased and the ancestor or descendant (as the case may be); and,

- in the collateral line, the number of generations between the blood relation and the nearest common ancestor, plus the number of generations between that common ancestor and the deceased.

A parent or child of the deceased would thus be related to him in the first degree, a grandparent or grandchild in the second degree, an uncle or aunt in the third degree, and so on.

No spouse or living blood relatives

[edit]If there are no relations of the deceased, by blood or by adoption, and no surviving spouse, the fiscus or State is entitled, after the lapse of thirty years, to claim the estate as bona vacantia (unclaimed property) in terms of the common law. The authority for this is the case of Estate Baker v Estate Baker. In these circumstances the State is not an "heir," and the estate is not "inherited." It merely accrues to the State.

Disqualification and renunciation

[edit]The Law of Succession Amendment Act, 1992,[11] which came into operation on 1 October 1992, amended the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 as regards the rules for the disqualification of and the renunciation by an intestate heir of his inheritance. If a person is disqualified from being an intestate heir of the deceased, the benefit which the heir would have received had the heir not been disqualified, devolves as if the heir had died immediately before the death of the deceased, and as if the heir had not been disqualified from inheriting.[12]

Where an heir who stands to inherit along with the surviving spouse (provided that that heir is not a minor or mentally ill) renounces his or her intestate benefit, such benefit vests in the surviving spouse.[13] Where there is no surviving spouse, the benefit devolves as if the descendant had died immediately before the death of the deceased.[12]

Customary law

[edit]Section 23 of the Black Administration Act, 1927 stated that, when African persons died intestate, their estates devolved in terms of the rules of primogeniture. Women and children, therefore, were excluded from inheriting under this Act. The case of Bhe v The Magistrate, Khayelitsha changed this by striking down section 23 as unconstitutional.

There is a statute not yet in force (the Reform of Customary Law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act, 2009) which states that the estates of persons subject to customary law who die intestate will devolve in terms of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987.[14] This Act thus modifies the customary-law position.

A testator living under a system of customary law may still use his or her freedom of testation to stipulate that the customary law of succession must be applicable to his or her estate. In such a case, it would be necessary to apply the customary law of succession to the deceased estate.

If the customary law of succession is applicable, it is important to distinguish between the order of succession in a monogamous and polygynous household.

Intestate succession and Muslim marriages

[edit]Persons married in terms of Muslim rites are not recognised in South African law as "spouses" proper. All references, therefore, to "spouses" in the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 do not apply. The courts in Daniels v Campbell and Hassam v Jacobs, however, have held that persons married in terms of Muslim rites may inherit as if they were spouses proper.

Intestate succession and Hindu marriages

[edit]Persons married in terms of Hindu rites are not recognised in South African law as "spouses" proper. All references to "spouses" in the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 accordingly do not apply. The court in the case of Govender v Ragavayah, however, held that persons married in terms of Hindu rites may inherit as if they are spouses proper.

Intestate succession and permanent same-sex life partnerships

[edit]Before the Civil Union Act, 2006, partners in a permanent same-sex life partnership were not allowed to marry, and so could not inherit from each other intestate. The case of Gory v Kolver changed this position, with its finding that such partners could inherit intestate.

There is a proposed amendment to section 1 of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987, which will include partners in a permanent same-sex life partnership in which the partners have undertaken reciprocal duties of support in the definition of "spouse." The amendment of the Act, it has been argued, is ill-advised. The memorandum to the Amendment Bill cites Gory v Kolver as authority, but it has been suggested that the situation which prevailed at the time that this case was heard no longer exists, due to the advent of the Civil Union Act, 2006. The decision in Gory v Kolver case was predicated on the fact that the parties were not able to formalise their relationship in any way. On the evidence, the parties had undertaken mutual duties of support. Had it been possible for them to do so, they would almost certainly have formalised their relationship. Were the parties in that situation presently, they would have the option of formalising their relationship under the Civil Union Act, 2006. The survivor would be considered a "spouse" for the purposes of the Intestate Succession Act,1987. The net effect of the proposed amendment, it has been argued, is that it elevates same-sex partnerships to a level superior to that of heterosexual life partnerships.

It has been suggested that the proposed Domestic Partnership Bill will address the concerns of parties to a same-sex or heterosexual relationship insofar as intestate succession is concerned. More importantly, both types of relationship (same-sex and heterosexual) will be on an equal footing under the proposed Domestic Partnership Bill. This arguably would not be the case if the proposed amendment to the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 were signed into law.

Furthermore, the memorandum to the amendment Bill states that the proposed amendment limits the application of the clause to cases where the court is satisfied that the partners in question were not able to formalise their relationship under the Civil Union Act, 2006. The question remains, however: What exactly would these circumstances be?

Intestate succession and permanent heterosexual life partnerships

[edit]It is trite that the survivor of a heterosexual life partnership enjoys no benefits as a spouse under the Intestate Succession Act, 1987; nor may the survivor of a heterosexual life partnership claim maintenance from the deceased estate in terms of the Maintenance of Surviving Spouses Act, 1990.[15]

The Draft Domestic Partnerships Bill seeks to address those persons who do not wish to marry but who still want to formalise their partnerships. Section 20 of the Bill states that the definition of "spouse" in section 1 of the Intestate Succession Act, 1987 will include a registered domestic partner.

Section 26 of the Bill also provides that an unregistered domestic partner may apply for an order for intestate succession, and that the court will take into account, inter alia,

- the duration and nature of the relationship;

- the nature and extent of the common residence;

- the financial interdependence of the parties;

- the care and support of children of the parties; and

- the performance of household duties.

The Bill does not make the relationship between the parties a "marriage" or a "civil union" proper; it merely allows for the registration of the partnership.

References

[edit]- ^ See Ex parte Stephens' Estate 1943 CPD 397.

- ^ a b Act 81 of 1987.

- ^ J.A. Schiltkamp, "On Common Ground: Legislation, Government, Jurisprudence, and Law in the Dutch West Indian Colonies in the Seventeenth Century", A Beautiful and Fruitful Place: Selected Rensselaerwijck Papers, vol. 2 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2011), 228.

- ^ Grotius 2.28.

- ^ Van Leeuwen CF 1.3.16.

- ^ Act 25 of 1961.

- ^ Act 13 of 1934.

- ^ Act 74 of 1983.

- ^ Statutory language: "out of community of property and not subject to accrual"

- ^ Statutory language: "out of community of property but with accrual"

- ^ Act 43 of 1992.

- ^ a b The Intestate Succession Act, 1987, section 1(7), as inserted by section 14(b) of the Law of Succession Amendment Act, 1992

- ^ The Intestate Succession Act, 1987, section 1(6), as inserted by section 14(b) of the Law of Succession Amendment Act, 1992

- ^ The Reform of Customary Law of Succession and Regulation of Related Matters Act, 2009, section 2(1)

- ^ Volks v Robinson 2005 (5) BCLR 446 (CC)

Books

[edit]- M M Corbett, Gys Hofmeyr, & Ellison Kahn. Law of Succession in South Africa, 2nd edn. Cape Town: Juta, 2003.

- Jacqueline Heaton & Anneliese Roos. Family and Succession Law in South Africa, 2nd rev. edn. Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer, 2016.

- Jamneck, Juanita, Christa Rautenbach, Mohamed Paleker, Anton van der Linde, & Michael Wood-Bodley. The Law of Succession in South Africa. Edited by Juanita Jamneck & Christa Rautenbach. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Marius J de Waal. "Intestate Succession in South Africa". Reid, de Waal and Zimmerman (eds). Intestate Succession. (Comparative Succession Law, Volume 2). Oxford University Press. 2015. Chapter 10. Pages 248 to 273.

KSF

KSF