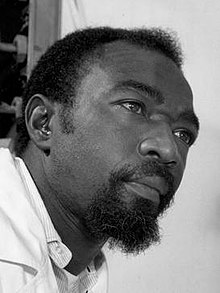

James Andrew Harris

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 5 min

James Andrew Harris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 26, 1932 Waco, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | December 12, 2000 (aged 68) |

| Education | Huston–Tillotson College California State University, East Bay |

| Occupation | Nuclear chemist |

| Notable work | Co-discovery of rutherfordium and dubnium |

James Andrew Harris (March 26, 1932 – December 12, 2000) was an American radiochemist who was involved in the discovery of elements 104 and 105 (rutherfordium and dubnium, respectively). Harris was the head of the Heavy Isotopes Production Group, part of the Nuclear Chemistry Division of the University of California, Berkeley. Harris is known for being the first African American to contribute to the discovery of new elements.[1]

Personal life

[edit]James A. Harris was born on March 26, 1932, in Waco, Texas.[2] Harris' parents divorced when he was young, after which he moved to Oakland, California with his mother.[1] Harris met his wife Helen at Huston-Tillotson College, where they were both completing their undergraduate studies; they were married in 1957 and had five children, Cedric, Keith, Hilda, Kimberly, and James II. Between the time of his graduation from college and his marriage, Harris was drafted and served in the Army as a personnel supervisor specialist.[3][4] His hobbies included golf, traveling, and community activities.[1] James A. Harris died of a sudden illness on December 12, 2000.[5]

Education

[edit]James A. Harris graduated from McClymonds High School in Oakland, California.[6] After high school, Harris returned to Texas where he attended Huston-Tillotson College in Austin.[7] He initially entered college on a music scholarship, but switched to studying chemistry and received a bachelor of science degree in 1953.[4][3] In 1975, Harris received a master's degree in Public Administration at California State University, Hayward. Harris was awarded an honorary doctorate from Huston-Tillotson College in 1973 for his co-discovery of rutherfordium and dubnium.[7] Harris was also a brother of the African-American Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[7]

Career

[edit]Harris' first job in chemical research was as a radiochemist at Tracerlab Inc., a commercial research lab in Richmond, California; he worked there for five years.[8] Harris left Tracerlab Inc. to work on isotope division in the nuclear chemistry department of the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory at University of California-Berkeley.[2] His early work at the lab involved studying beta decay in the Beta Spectroscopy Group. He also worked on a project to improve neutron activation analysis with germanium semiconducting detectors.[4] Harris then joined the Heavy Isotopes Production Group on the team tasked with producing new heavy elements via atom bombardment. Harris' job was to design and purify targets that would be used in Berkeley's Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator to discover elements 104 and 105. These targets needed minimal impurities of elements such as lead to work.[9] Harris' colleagues praised his work, saying that it was high quality and very good for heavy element research.[9] He and his colleagues also conducted what they called the “first aqueous chemistry of element 104”, to determine how the new element behaved and thus where it should be placed on the periodic table.[4]

Two research teams were simultaneously working to discover elements 104 and 105. One was Harris's team at the University of California-Berkeley and the other was a team of Russian scientists. Both teams successfully isolated the two elements around the same time in 1969 and 1970, so there is dispute over which team was actually the first to isolate the elements. In 1997 the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry settled the dispute: element 104 was given the name suggested by the American research team, rutherfordium, after the influential British physicist. Element 105 was subsequently given the name dubnium, representing the city, Dubna, where the Russian team worked.[10]

As head of the Heavy Isotopes Production Group, Harris and his team continued the search for other heavy elements which might be more stable and therefore useful for medicine, energy, or other purposes.[11] Six years after discovering elements 104 and 105, Harris took a position with the Berkeley Lab Office of Equal Opportunity. There he worked with Benjamin Pope to recruit more women and minorities to work at the lab, focusing on outreach at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and forming partnerships with engineering colleges.[4] In 1977, Harris was promoted to Head of Engineering and Technical Services Division.[7] He retired in 1988.

During his career and after retirement, Harris worked with students in grade school and at the university level to encourage African Americans students into the sciences. This work earned him numerous awards from organizations including the National Organization for Equal Opportunity in Education, the Urban League and the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers.[8][11]

Awards

[edit]- Honorary PhD from Huston-Tillotson College (1973)

- Scientific Merit Award from the Mayor of Richmond, CA

- Certificate of Merit from the Black Dignity Science Association

Organizations

[edit]Harris was a part of the following organizations:[2]

- National Society of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers

- Nuclear Target Society

- American Chemical Society

- AEC Transplutonium Program

- Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "James A. Harris". www.cpnas.org. National Academy of Sciences. 2002. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ a b c Brown, M.C. "James Andrew Harris: Nuclear Chemist". www.fofweb.com. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ a b "Harris, James A." Online Infobase. Facts on File. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Frederick-Frost, Kristen (1 Mar 2021). "The Life and Career of James Andrew Harris: Let's Ask More of History". Journal of Chemical Education. 98 (4): 1242–1248. Bibcode:2021JChEd..98.1242F. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01054. S2CID 233776292.

- ^ Burke, Anabel. "James Andrew Harris". Waco History. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- ^ "James Andrew Harris".

- ^ a b c d "James Andrew Harris: Nuclear Chemist". webfiles.uci.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-04-30. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ^ a b "James A. Harris". Physics Today. 26 Mar 2018. doi:10.1063/pt.6.6.20180326a. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ a b Gonzales, Lisa (2000). "Jim Harris left his mark on science and community". Berkeley Lab Currents. Berkeley Lab.

- ^ Green, John. "Who was the African American Nuclear Scientist who discovered the Elements Rutherfordium & Hahnium?". Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Johnson, Bethany (28 Oct 2020). "James Andrew Harris (1932-2000)". Black Past. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

KSF

KSF