Japanese migration to Malaysia

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

在マレーシア日本人 | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 24,545 (2022)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

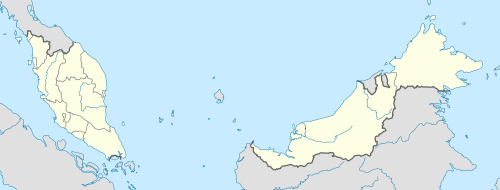

| 5,275[2] | |

| 1,655[2] | |

| 944[2] | |

| 400[2][3] | |

| 245[2] | |

| 212[2] | |

| 138[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Japanese, Malay, English[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Japanese diaspora | |

The history of Japanese migration in Malaysia goes back to the late 19th century, when the country was part of the British Empire as British Malaya.

Migration history

[edit]| Year | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 14 | 100 | 120 |

| 1901 | 87 | 448 | 535 |

| 1911 | 337 | 1,692 | 2,029 |

| 1921 | 757 | 1,321 | 2,078 |

| 1931 | 533 | 790 | 1,323 |

Even during the relatively open Ashikaga shogunate (1338–1573), Japanese traders had little contact with the Malayan peninsula; after the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate and their policy of national isolation, most contact came to an end, though traders from the Ryukyu Islands continued to call at Malacca.[6] The 1911 census found 2,029 Japanese in Malaya, four-fifths female; however, other sources suggest the population may already have reached four thousand people by then.[7] In British North Borneo (today the Malaysian state of Sabah), the port city of Sandakan was a popular destination; however, the city today has little trace of their former presence, besides an old Japanese cemetery.[8]

The December 1941 Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation of Malaya brought many Imperial Japanese Army soldiers to the country, along with civilian employees of Japanese companies. After the Surrender of Japan ended the war, Japanese civilians were mostly repatriated to Japan; about 6,000 Japanese civilians passed through the transit camp at Jurong, Singapore. In the late days of the war and the post-war period, around 200 to 400 Japanese holdouts were known to have joined the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), aiming to fight against the British post-war attempt to re-establish control of Malaya.[9] The largest concentration at Kuala Kangsar, Perak seem to have been executed by Lai Teck; however, others would go on to join the Malayan Communist Party and remain hidden in the jungles.[10] As late as 1990, two elderly Japanese civilians from that period remained in hiding with the MCP in the jungles on the Malaysia–Thailand border. They emerged and requested repatriation to Japan after the end of the Communist insurgency in Malaysia (1968–89). In media interviews these individuals stated that they remained behind because they felt morally obligated to aid the fight for Malayan independence from the British.[11]

In the late 2000s, Malaysia began to become a popular destination for Japanese retirees. Malaysia's My Second Home retirement programme received 513 Japanese applicants from 2002 until 2006.[12] Motivations for choosing Malaysia include the low cost of real-estate and of hiring home care workers.[13] Such retirees sometimes refer to themselves ironically as economic migrants or even economic refugees, referring to the fact that they could not afford as high a quality of life in retirement, or indeed to retire at all, were they still living in Japan.[14] However, overall, between 1999 and 2008, the population of Japanese expatriates in Malaysia fell by one-fifth.[15]

Business and employment

[edit]During the early Meiji era, Japanese expatriates in Malaya consisted primarily of "vagabond sailors" and "enslaved prostitutes".[6] Most came from Kyushu. The Japanese government first ignored them, but in the era of rising national pride following the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, came to see them as an embarrassment to Japan's image overseas; however, their presence and the money they earned formed the basis for the early Japanese commercial enclaves and small businesses in Malaysia.[16] Soon after, the expansion of those businesses, and of Japan's commercial interests in Southeast Asia, would spark changes in the composition of the population.[6] Japan worked with local colonial authorities to suppress Japanese women's participation in the sex trade, and by the 1920s most prostitutes had been forced to repatriate to Japan.[17]

By the early 20th century, most Japanese in Malaya worked in rubber cultivation. At the peak of the industry's success in 1917, there were 1,776 Japanese employed on rubber plantations.[18] They worked primarily at Japanese-owned plantations, concentrated in Johor, Negeri Sembilan, and Borneo.[19] By 1917, Japanese planters owned 170,000 acres (690 km2) in Johor alone.[20] However, British legislation enacted that year restricted the sale of land greater than 50 acres (200,000 m2) to foreigners; the Japanese consul lodged a strong protest, as the Japanese were the most-affected among all foreigners, however to no avail.[21] By the mid-1920s, the number of rubber plantation workers had declined to around 600, in concert with the fall in international rubber prices.[19] Between 1921 and 1937, 18 of the 23 Japanese corporate-owned plantations in Malaya shut down.[22]

More urbanised Penang shows a somewhat different pattern of economic development. As in other parts of Malaya, the early Japanese community there was based around prostitution. As early as 1893, the community had set up its own cemetery. In a form of "spillover effect", other Japanese tertiary sector workers followed them and set up their own businesses catering to them, such as medical and dental services and hotels; these also found customers among local people, who saw them as high quality while being lower cost than the equivalents patronised by Europeans. The Japanese were also credited with opening the island's first cinemas and photo studios. Many of these businesses clustered around Cintra Street and Kampung Malabar (see list of streets in George Town, Penang). With the growth in the number of Japanese ocean-liners travelling between Japan and Europe which called at Penang, the hoteliers were able to expand their customer base beyond prostitutes; they used the capital and experience they had already accumulated to establish higher-quality establishments to cater to the needs of travellers.[23]

In the 1970s, the number of Japanese subsidiaries and joint ventures in Malaysia increased significantly.[24] By 1979, roughly 43% of Japanese JVs in Malaysia were engaged in manufacturing, primarily in the electronics, chemicals, wood products, and chemicals.[25] The movement of Japanese manufacturing to southeast Asia, including Malaysia, intensified with the implementation of strong-yen monetary policies under the 1985 Plaza Accord.[26] Japanese subsidiary companies in Malaysia show a tendency to employ a far higher number of expatriate staff than their British or American competitors; a 1985 survey found a figure of 9.4 expatriate Japanese staff per subsidiary, though noted a declining trend.[27]

Interethnic relations

[edit]In the aftermath of the 1931 Mukden Incident which led to the establishment of Manchukuo, anti-Japanese sentiment began to grow among the ethnic Chinese population of Malaysia.[28] In Penang, Chinese community leaders encouraged people to boycott Japanese shops and goods. The hostile environment contributed to the outflow of Japanese civilians. In the lead up to and during the Japanese occupation of Malaya, Chinese people suspected that the remaining Japanese were spies and informants for the Japanese government, though in fact the major collaborators were local Chinese who dealt in Japanese goods, as well as people from Taiwan who, bilingual in Hokkien and Japanese, served as intermediaries between the locals and the Japanese.[23]

Japanese management practises in Malaysia in the 1980s and 1990s show a different pattern of interethnic relations. Some authors suggest that the Japanese show favouritism in promotion towards Malaysian Chinese over bumiputera, due to their closer cultural background.[29] Despite efforts to localise the management of JVs, most managers continue to be expatriates. One author, however, noted a repeating pattern in several companies she studied: there would be a single high-up local manager, an ethnic Chinese man who attended university in Japan and married a Japanese woman; however, the Japanese wives of other expatriates tend to look down on such women, and there is little social contact between them.[30] Japanese staff in Japanese JVs and subsidiary companies tend to form a "closed and exclusive circle", and develop few personal relationships outside the workplace with their Malaysian peers and subordinates. This is often attributed to a language barrier, yet Japanese sent to Malaysia tend to possess at least some proficiency in English; as a result, other scholars suggest that cultural and religious differences, as well as the short stay of most Japanese business expatriates, play a role as well.[4]

Organisations

[edit]

The Japanese Association of Singapore, established in 1905, would go on to establish branches in all of the Malay states. It was closely watched by the police intelligence services.[31]

There are Japanese day schools in a number of major cities in Malaysia, including the Japanese School of Kuala Lumpur in Subang, Selangor,[32] the Japanese School of Johor,[33] the Kinabalu Japanese School,[34] and the Penang Japanese School.[35] The Perak Japanese School is a supplementary education programme in Ipoh, Perak.[36]

Japanese expatriates prefer to live in high-rise apartment buildings close to Japanese schools or other international schools.[37]

In popular culture

[edit]In Japan, interest in the history of Japanese prostitutes in Malaysia in the early days of the 20th century was sparked by Tomoko Yamazaki's 1972 book Sandakan hachiban shokan, a recording of oral history of women from the Amakusa Islands who had gone to Sandakan and then returned to Japan in the 1920s.[38] Yamazaki's book went on to win the Oya Soichi Nonfiction Prize (established by novelist Sōichi Ōya), and enjoyed nationwide popularity. It was fictionalised as a series of popular films, the first of which, the 1972 Sandakan No. 8 directed by Kei Kumai, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[39]

Notable people

[edit]This is a list of Japanese expatriates in Malaysia and Malaysians of Japanese descent.

- Endon Mahmood, late wife of ex-Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, born to a Malay father and a Japanese mother[40]

- Tun Fuad Stephens, first Chief Minister of the state of Sabah in Malaysia, and the first Huguan Siou or Paramount Leader of the Kadazandusun community

- Syatilla Melvin, Malaysian actress and model

- Tadashi Takeda, footballer for JEF United Ichihara Chiba, born in Malaysia[41]

- Yuumi Kato, Japanese model and Miss Universe Japan 2018

- Koreyoshi Kurahara, director and screenwriter, born in Sarawak

- Chef Wan, Malaysian celebrity chef

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The number of Japanese residents (April 2014)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Embassy of Japan 2009, §2

- ^ "Japan looks forward to strengthening ties with Sabah". Bernama. The Borneo Post. 1 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ a b Imaoka 1985, p. 354

- ^ Denker 1998, p. 3, based on British censuses

- ^ a b c Leng 1978, p. 163

- ^ Denker 1998, pp. 2–3

- ^ Warren 2000, p. 9

- ^ Bayly & Harper 2007, p. 272

- ^ Bayly & Harper 2007, p. 273

- ^ "2 Japanese emerge after 45 years of fighting with guerrillas in Jungle", Deseret News, 12 January 1990, archived from the original on 23 October 2012, retrieved 20 June 2011

- ^ Ono 2008, pp. 154–155

- ^ Ono 2008, pp. 155–157

- ^ Ono 2008, p. 159

- ^ Embassy of Japan 2009, §1

- ^ Furuoka et al. 2007, p. 314

- ^ Warren 2000, p. 5

- ^ Shimizu 1993, p. 81

- ^ a b Shimizu 1993, p. 82

- ^ Leng 1978, p. 169

- ^ Denker 1998, p. 6

- ^ Shimizu 1993, p. 83

- ^ a b Liang, Clement (18 September 2007), "The Pre-War Japanese Community in Penang (1890–1940)", Penang Media, archived from the original on 24 August 2011, retrieved 20 June 2011

- ^ Imaoka 1985, pp. 339–342

- ^ Smith 1994, p. 154

- ^ Furuoka et al. 2007, p. 319

- ^ Imaoka 1985, p. 348

- ^ Furuoka et al. 2007, p. 316

- ^ Smith 1994, p. 160

- ^ Smith 1994, p. 175

- ^ Denker 1998, p. 5

- ^ "School Outline Archived 8 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine." Japanese School of Kuala Lumpur. Retrieved on January 13, 2015. "Saujana Resort Seksyen U2, 40150, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia"

- ^ Home page Archived 16 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Japanese School of Johor. Retrieved on January 15, 2015. "No.3, Jalan Persisiran Seri Alam, 81750 Johor Bahru, Johor Darul Takzim, West Malaysia."

- ^ Home page. Kinabalu Japanese School. Retrieved on January 15, 2015. "〒88450 Lorong Burong Ejek House No.8, Jalan Tuaran, Miles 3.5, 88450, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia"

- ^ Home page[usurped]. Penang Japanese School. Retrieved on January 15, 2015. "140.Sungei Pinang Road 10150 Penang,Malaysia."

- ^ アジアの補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Japanese expatriates prefer high-rise condominiums with schools nearby", New Straits Times, 10 February 2001, archived from the original on 4 November 2012, retrieved 20 February 2010

- ^ Warren 2000, p. 3

- ^ Warren 2000, p. 2

- ^ Koh, Lay Chin (21 October 2005), "Endon's legacy to the country", New Straits Times, retrieved 20 April 2010[permanent dead link]

- ^ "36 Tadashi Takeda", Team Roster for 2008, JEF United, 2008, archived from the original on 3 August 2008, retrieved 19 April 2010

Sources

[edit]- Bayly, Christopher Alan; Harper, Timothy Norman (2007), Forgotten wars: freedom and revolution in Southeast Asia, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02153-2

- Denker, Mehmet Sami (1998), "Ties That Bind: Japan-Malaysian Economic Relations in Historical Perspective" (PDF), İktisadi ve idari bilimler fakültesi dergisi, 8 (1): 1–15, archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011

- Furuoka, Fumitaka; Lim, Beatrice; Mahmud, Roslinah; Katō, Iwao (2007), 東マレーシアと日本の歴史的関係に関する考察 (PDF), 東西南北 (in Japanese), vol. 15, pp. 309–321, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011

- Imaoka, Hiroki (1985), "Japanese management in Malaysia" (PDF), Southeast Asian Studies, 22 (4)[permanent dead link]

- Leng, Yuen-choy (1978), "The Japanese Community in Malaya before the Pacific War: Its Genesis and Growth", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 9 (2): 163–179, doi:10.1017/s0022463400009735, JSTOR 20062723, S2CID 161466410

- Ono, Mayumi (2008), "Long-Stay Tourism and International Retirement Migration: Japanese Retirees in Malaysia" (PDF), in Yamashita, Shinji (ed.), Transnational migration in East Asia: Japan in a comparative focus, Senri Ethnological Reports, vol. 77, pp. 151–162, ISBN 978-4-901906-57-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011

- Shiraishi, Saya; Shiraishi, Takashi, eds. (1993), The Japanese in colonial Southeast Asia, Southeast Asian Publications, vol. 3, Cornell University, ISBN 978-0-87727-402-5. Chapters cited:

- Shiraishi, Saya; Shiraishi, Takashi (1993), "The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia: An Overview", The Japanese in colonial Southeast Asia, pp. 1–20

- Shimizu, Hajime (1993), "The Pattern of Economic Penetration of Prewar Singapore and Malaysia", The Japanese in colonial Southeast Asia, pp. 63–86

- Smith, Wendy A. (1994), "A Japanese Factory in Malaysia: Ethnicity as a management ideology", in Sundaram, Jomo Kwame (ed.), Japan and Malaysian development: in the shadow of the rising sun, Routledge, pp. 154–181, ISBN 978-0-415-11583-4

- 田邉 保博 [Tanabe Yasuhiro] (2003), マレイシア・クアラルンプール日本人学校の教育事情, Bulletin of the Center for Research in International Education (in Japanese) (26): 109–111, archived from the original on 13 August 2011

- コタキナバル日本人学校, Kaigai-Shijo-Kyōiku = Japan Overseas Educational Services 海外子女教育 (in Japanese), 32 (3), 2005, ISSN 0287-7058

- Warren, James F. (September 2000), "New Lands, Old Ties and Prostitution: A Voiceless Voice", Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, 31 (4): 396–404, doi:10.1017/s002246340001763x, PMID 19123285, S2CID 46142556, retrieved 27 August 2012

- マレーシア在留邦人数の調査結果について, Malaysia: Embassy of Japan, 14 February 2009

Further reading

[edit]- Abdullah, Syed R. S.; Keenoy, Tom (1995). "Japanese managerial practices in the Malaysian Electronics Industry: Two case studies". Journal of Management Studies. 32 (6): 747–766. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1995.tb00150.x.

- Raduan, Che Rose (2002). Japanese style management abroad: The case of Malaysian subsidiaries. Selangor, Malaysia: Prentice Hall, Pearson Education. ISBN 978-983-2473-01-5. OCLC 51554618.

- Smith, Wendy A. (1993). "Japanese management in Malaysia". Japanese Studies. 13 (1): 50–76. doi:10.1080/10371399308521875.

KSF

KSF