Jay Berwanger

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

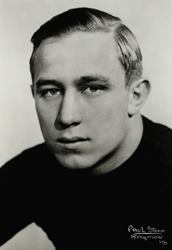

Berwanger at the University of Chicago, early 1930s | |

| No. 99 | |

|---|---|

| Position | Halfback |

| Personal information | |

| Born: | March 19, 1914 Dubuque, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died: | June 26, 2002 (aged 88) Oak Brook, Illinois, U.S. |

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) |

| Weight | 195 lb (88 kg) |

| Career history | |

| College |

|

| High school | Dubuque |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| College Football Hall of Fame (1954) | |

John Jacob "Jay" Berwanger (March 19, 1914 – June 26, 2002) was an American college football player and referee.[1] In 1935, Berwanger was the first recipient of the Downtown Athletic Club Trophy, renamed the Heisman Trophy the following year. At its inception, the award was given to "the most valuable player east of the Mississippi."[2] In 1936, Berwanger became the first player drafted into the National Football League in its inaugural 1936 NFL draft, although he did not play professionally due to a salary dispute.

College career

[edit]After attending Dubuque High School in Iowa, Berwanger played college football for the Chicago Maroons football team of the University of Chicago for the 1933 though 1935 seasons, scoring 22 touchdowns in 24 games.[3] He was a star halfback for Chicago, where he was known as the "one man football team".[4] Playing in the one-platoon system era, he was also a linebacker and return specialist.[3] Berwanger was also nicknamed "the Flying Dutchman", although his ancestry was actually German, and the "Man in the Iron Mask", because he wore a special face guard to protect his twice-broken nose.[5]

Berwanger was also awarded the Chicago Tribune Silver Football as the most valuable player in the Big Ten Conference and earned unanimous All-America honors. In a 1934 game against the Michigan Wolverines, Berwanger left his mark on Michigan center Gerald Ford in the form of a distinctive scar beneath the future U.S. president's left eye.[6] In 1935, Berwanger became the first recipient of the Downtown Athletic Club Trophy, renamed the Heisman Trophy the following year—John Heisman was then the club's athletic director, and after Heisman's death in October 1936 the trophy was expanded to become a national honor and named the Heisman Trophy.[2]

Berwanger also competed in track and field for Chicago, setting a school decathlon record in 1936 that stood until 2007.[7] He was a brother of the Psi Upsilon fraternity.[8]

Heisman season

[edit]During the 1935 campaign, when he won what was to become the Heisman Trophy, Berwanger rushed for 577 yards, passed for 405, returned kickoffs for 359 yards, scored six touchdowns, and added five extra points for 41 points.[9] His team went 4–4 with a 2–3 mark in the Big Ten that season.[5] In voting for the award, Berwanger received 84 votes, finishing ahead of Army's Monk Meyer, Notre Dame's William Shakespeare, and Princeton's Pepper Constable.[5] He won 43% of the eligible votes cast.[10]

After college

[edit]In 1936, Berwanger was the first player ever drafted into the National Football League in its inaugural 1936 NFL draft.[11] The Philadelphia Eagles selected him, but did not think they would be able to meet his reported salary demands of $1,000 per game.[12] They traded his negotiating rights to the Chicago Bears for tackle Art Buss.[13] Berwanger initially chose not to sign with the Bears in part to preserve his amateur status so that he could compete for a spot on the U.S. team for the 1936 Summer Olympics in the decathlon.[14]

After he missed the Olympics cut, Berwanger and Bears' owner George Halas were unable to reach an agreement on salary; Berwanger was requesting $15,000 ($339,892 in 2024) and Halas's final offer was $13,500 ($305,903 in 2024).[15] Instead, he took a job with a Chicago rubber company and also became a part-time coach at the University of Chicago.[16] Berwanger later expressed regret that he did not accept Halas's offer.[15]

To continue his athletic pursuits, Berwanger started playing rugby with the Chicago team, which then won 19 straight matches and a national championship, beating the team from New York, which coincidentally had the second Heisman winner, Yale's Larry Kelly. In 2016, Berwanger was inducted into the Rugby Hall of Fame.

Later life and honors

[edit]After graduating, Berwanger worked briefly as a sportswriter and later became a manufacturer of plastic car parts. He was very modest about the Heisman Trophy; unsure what to do with the trophy, he left it with his Aunt Gussie, who used it as a doorstop.[6] The trophy was later bequeathed to the University of Chicago Athletic Hall of Fame, where it is on display. There is also a replica of the Heisman on display in the trophy case in the Nora Gymnasium at Dubuque Senior High School in Dubuque, Iowa. He is a member of both the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame and Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame.

Berwanger died after a lengthy battle with lung cancer at his home in Oak Brook, Illinois, on June 26, 2002, at the age of 88.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Curme, Emmett (October 3, 1954). "Knickered Football Officials Whistle While They Work". Chicago Tribune. pp. 3–4. Retrieved April 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "New York Pays High Honors to Berwanger". Chicago Daily Tribune. December 11, 1935. p. 27.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame: Jay Berwanger". footballfoundation.org. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ "Jay Berwanger, Chicago Halfback, Voted Outstanding Athlete in the Big Ten". The New London Day. December 6, 1935. p. 21. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Heisman Trophy – Jay Berwanger – Heisman Winners". heismantrophy.com. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Chicago legend passes on; Berwanger dies at age 88". University of Chicago Chronicle. July 11, 2002. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "University of Chicago Men's Track & Field Honor Rolls". Athletics.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ^ "The story of Psi Upsilon". psiu.org. September 11, 2019.

- ^ "Jay Berwanger". University of Chicago Athletics. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ "1935 Heisman Trophy Voting". College Football at Sports-Reference.com. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "The first NFL draft takes place in Philadelphia in 1936". Chicago Tribune. February 10, 1936. p. 16. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "Chicago Bears Granted Option on Jay Berwanger". Milwaukee Journal. February 10, 1936. p. D4. Retrieved May 9, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Outstanding Pro Linemen Coming Here With Eagles". Reading Eagle. October 29, 1936. p. 24. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Berwanger is Seeking Berth on Olympic Track Team". The Youngstown Daily Vindicator. Associated Press. December 11, 1935. p. 12. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Kirksey, George (December 11, 1940). "Halas Dominates Pro Football League". Berkeley Daily Gazette. United Press International. p. 23. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "Jay Berwanger to Coach at Chicago". The Daily News. June 29, 1936. p. 6. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "Berwanger, first winner of Heisman Trophy, dies". Lewiston Morning Tribune. June 28, 2002. p. 2B. Retrieved May 10, 2011 – via Google News.

KSF

KSF