Jean Genet

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 23 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 23 min

This article has an unclear citation style. (November 2024) |

Jean Genet | |

|---|---|

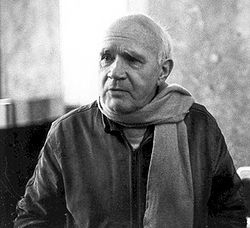

Genet in 1983 | |

| Born | 19 December 1910 Paris, France |

| Died | 15 April 1986 (aged 75) Paris, France |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | Theatre of Cruelty, erotic, theatre, absurdism |

| Subject | Crime, homosexuality, sadomasochism, existentialism |

| Literary movement | Theatre of the Absurd |

| Notable works | Our Lady of the Flowers (1943) The Thief's Journal (1949) The Maids (1947) The Balcony (1956) |

| Signature | |

Jean Genet (/ʒəˈneɪ/; French: [ʒɑ̃ ʒənɛ]; 19 December 1910 – 15 April 1986) was a French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist. In his early life he was a vagabond and petty criminal, but he later became a writer and playwright. His major works include the novels The Thief's Journal and Our Lady of the Flowers and the plays The Balcony, The Maids and The Screens.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Genet's mother was a prostitute who raised him for the first seven months of his life before placing him for adoption. Thereafter Genet was raised in the provincial town of Alligny-en-Morvan, in the Nièvre department of central France. His foster family was headed by a carpenter and, according to Edmund White's biography, was loving and attentive. While he received excellent grades in school, his childhood involved a series of attempts at running away and incidents of petty theft.

Detention and military service

[edit]For this and other misdemeanors, including repeated acts of vagrancy, he was sent at the age of 15 to Mettray Penal Colony where he was detained between 2 September 1926 and 1 March 1929. In Miracle of the Rose (1946), he gives an account of this period of detention, which ended at the age of 18 when he joined the Foreign Legion. He was eventually given a dishonorable discharge on grounds of indecency (having been caught engaged in a homosexual act) and spent a period as a vagabond, petty thief and prostitute across Europe—experiences he recounts in The Thief's Journal (1949).

Criminal career, prison, and prison writings

[edit]After returning to Paris in 1937, Genet was in and out of prison through a series of arrests for theft, use of false papers, vagabondage, lewd acts, and other offences. In prison Genet wrote his first poem, "Le condamné à mort", which he had printed at his own cost, and the novel Our Lady of the Flowers (1944).

In Paris, Genet sought out and introduced himself to Jean Cocteau, who was impressed by his writing. Cocteau used his contacts to get Genet's novel published, and in 1949, when Genet was threatened with a life sentence after ten convictions, Cocteau and other prominent figures, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Pablo Picasso, successfully petitioned the French President to have the sentence set aside. Genet would never return to prison.

Writing and activism

[edit]By 1949, Genet had completed five novels, three plays, and numerous poems, many controversial for their explicit and often deliberately provocative portrayal of homosexuality and criminality. Sartre wrote a long analysis of Genet's existential development (from vagrant to writer), entitled Saint Genet (1952), which was anonymously published as the first volume of Genet's complete works. Genet was strongly affected by Sartre's analysis and did not write for the next five years.

Between 1955 and 1961, Genet wrote three more plays as well as an essay called "What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet", on which hinged Jacques Derrida's analysis of Genet in his seminal work Glas. During this time, Genet became emotionally attached to Abdallah Bentaga, a tightrope walker. However, following a number of accidents and Bentaga's suicide in 1964, Genet entered a period of depression, and even attempted suicide himself.[2]

From the late 1960s, starting with an homage to Daniel Cohn-Bendit after the events of May 1968, Genet became politically active. He participated in demonstrations drawing attention to the living conditions of immigrants in France. Genet was censored in the United States in 1968 and later expelled when he was refused a visa. In an interview with Edward de Grazia, professor of law and First Amendment lawyer, Genet discusses the time he went through Canada for the Chicago congress. He entered without a visa and left with no issues.[3]

In 1970, the Black Panthers invited him to the United States, where he stayed for three months giving lectures, attended the trial of their leader, Huey Newton, and published articles in their journals. Later the same year he spent six months in Palestinian refugee camps, secretly meeting Yasser Arafat near Amman. Profoundly moved by his experiences in the United States and Jordan, Genet wrote a final lengthy memoir about his experiences, Prisoner of Love, which would be published posthumously.

Genet also supported Angela Davis and George Jackson, as well as Michel Foucault and Daniel Defert's Prison Information Group. He worked with Foucault and Sartre to protest police brutality against Algerians in Paris, a problem persisting since the Algerian War of Independence, when beaten bodies were to be found floating in the Seine.[citation needed] Genet expresses his solidarity with the Red Army Faction (RAF) of Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, in the article "Violence et brutalité", published in Le Monde, 1977.

In September 1982, Genet was in Beirut when the massacres took place in the Palestinian camps of Sabra and Shatila. In response, Genet published "Quatre heures à Chatila" ("Four Hours in Shatila"), an account of his visit to Shatila after the event. In one of his rare public appearances during the later period of his life, at the invitation of Austrian philosopher Hans Köchler, he read from his work during the inauguration of an exhibition on the massacre of Sabra and Shatila organized by the International Progress Organization in Vienna, Austria, on 19 December 1983.[4]

In the early summer of 1985, the year before his death, Genet was interviewed by the BBC. He told the interviewer controversial but not surprising details of his life such as he disliked France so much that he supported the Nazis when they invaded Paris. He compared the BBC interview to a police interrogation.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]Genet developed throat cancer and was found dead at Jack's Hotel in Paris on 15 April 1986 where his photograph and books remain. Genet may have fallen on the floor and fatally hit his head. He is buried in the Larache Christian Cemetery in Larache, Morocco.

Genet's works

[edit]Novels and autobiography

[edit]Throughout his five early novels, Genet works to subvert the traditional set of moral values of his assumed readership. He celebrates a beauty in evil, emphasizes his singularity, raises violent criminals to icons, and enjoys the specificity of homosexual gesture and coding and the depiction of scenes of betrayal. Our Lady of the Flowers (Notre Dame des Fleurs 1943) is a journey through the prison underworld, featuring a fictionalized alter-ego named Divine, usually referred to in the feminine. Divine is surrounded by tantes ("aunties" or "queens") with colorful sobriquets such as Mimosa I, Mimosa II, First Communion and the Queen of Rumania. The two auto-fictional novels Miracle of the Rose (Miracle de la rose 1946) and The Thief's Journal (Journal du voleur 1949) describe Genet's time in Mettray Penal Colony and his experiences as a vagabond and prostitute across Europe. Querelle de Brest (1947) is set in the port town of Brest, where sailors and the sea are associated with murder. Funeral Rites (1949) is a story of love and betrayal across political divides, written for the narrator's lover, Jean Decarnin, killed by the Germans in WWII.

Prisoner of Love, published in 1986 after Genet's death, is a memoir of his encounters with Palestinian fighters and Black Panthers. It has a more documentary tone than his fiction.

Art criticism

[edit]Genet wrote an essay on the work of the Swiss sculptor and artist Alberto Giacometti titled L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti. It was highly praised by major artists, including Giacometti and Picasso. Genet wrote in an informal style, incorporating excerpts of conversations between himself and Giacometti. Genet's biographer Edmund White said that, rather than write in the style of an art historian, Genet "invented a whole new language for discussing" Giacometti, proposing "that the statues of Giacometti should be offered to the dead, and that they should be buried."[5]

Plays

[edit]Genet's plays present highly stylized depictions of ritualistic struggles between outcasts of various kinds and their oppressors.[6] Social identities are parodied and shown to involve complex layering through manipulation of the dramatic fiction and its inherent potential for theatricality and role-play. Maids imitate one another and their mistress in The Maids (1947); the clients of a brothel simulate roles of political power before, in a dramatic reversal, actually becoming those figures, all surrounded by mirrors that both reflect and conceal, in The Balcony (1957). Most strikingly, Genet offers a critical dramatisation of what Aimé Césaire called negritude in The Blacks (1958), presenting a violent assertion of black identity and anti-white virulence framed in terms of mask-wearing and roles adopted and discarded. His most overtly political play is The Screens (1964), an epic account of the Algerian War of Independence. He also wrote another full-length drama, Splendid's, in 1948 and a one-act play, Her (Elle), in 1955, though neither was published or produced during Genet's lifetime.

The Maids was the first of Genet's plays to be staged in New York, produced by Julie Bovasso at Tempo Playhouse in New York City in 1955. The Blacks was, after The Balcony, the third of Genet's plays to be staged in New York. The production was the longest running Off-Broadway non-musical of the decade. Originally premiered in Paris in 1959, this 1961 New York production ran for 1,408 performances. The original cast featured James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Browne, Louis Gossett Jr., Cicely Tyson, Godfrey Cambridge, Maya Angelou and Charles Gordone.

Film

[edit]In 1950, Genet directed Un Chant d'Amour, a 26-minute black-and-white film depicting the fantasies of a homosexual male prisoner and his prison warden. Genet is also credited as co-director of the West German television documentary Am Anfang war der Dieb (In the Beginning was the Thief) (1984), along with his co-stars Hans Neuenfels and François Bondy.

Genet's work has been adapted for film and produced by other filmmakers. In 1982, Rainer Werner Fassbinder released Querelle, his final film, based on Querelle of Brest. It starred Brad Davis, Jeanne Moreau and Franco Nero. Tony Richardson directed Mademoiselle, which was based on a short story by Genet. It starred Jeanne Moreau with the screenplay written by Marguerite Duras. Todd Haynes' Poison was based on the writings of Genet.

Several of Genet's plays were adapted into films. The Balcony (1963), directed by Joseph Strick, starred Shelley Winters as Madame Irma, Peter Falk, Lee Grant and Leonard Nimoy. The Maids was filmed in 1974 and starred Glenda Jackson, Susannah York and Vivien Merchant. Italian director Salvatore Samperi in 1986 directed another adaptation for film of the same play, La Bonne (Eng. Corruption), starring Florence Guerin and Katrine Michelsen.

In popular culture

[edit]Genet made an appearance by proxy in the pop charts when David Bowie released his 1972 hit single "The Jean Genie". In his 2005 book Moonage Daydream, Bowie confirmed that the title "...was a clumsy pun upon Jean Genet".[7] A later promo video combines a version of the song with a fast edit of Genet's 1950 film Un Chant d'Amour. Genet is referenced in the song "Les Boys" from the 1980 Dire Straits album "Making Movies". The 2023 French film Little Girl Blue, starring Marion Cotillard, traces the repercussions of Genet's sexual abuse of 11-year-old Carole Achache, the daughter of his friend Monique Achache. The 1991 film Poison directed by Todd Haynes was based on the writings on Jean Genet. Pete Doherty of The Libertines cites Genet as one of his main influences. In his 2009 debut solo single The Last of the English Roses, he recites an excerpt from Genet's 1946 novel Miracle of the Rose. The cover of The Books of Albion: The Collected Writings of Peter Doherty takes its inspiration from the first English edition of Genet's Our Lady of the Flowers, published in 1949, and includes clippings of and references to various Genet works.

List of works

[edit]Novels and autobiography

[edit]Entries show: English-language translation of title (French-language title) [year written] / [year first published]

- Our Lady of the Flowers (Notre Dame des Fleurs) 1942/1943

- Miracle of the Rose (Miracle de la Rose) 1946/1951

- Funeral Rites (Pompes Funèbres) 1947/1953

- Querelle of Brest (Querelle de Brest) 1947/1953

- The Thief's Journal (Journal du voleur) 1949/1949

- Prisoner of Love (Un Captif Amoureux) 1986/1986

Drama

[edit]Entries show: English-language translation of title (French-language title) [year written] / [year first published] / [year first performed]

- ′adame Miroir (ballet) (1944). In Fragments et autres textes, 1990 (Fragments of the Artwork, 2003)

- Deathwatch (Haute surveillance) 1944/1949/1949

- The Maids (Les Bonnes) 1946/1947/1947

- Splendid's 1948/1993/

- The Balcony (Le Balcon) 1955/1956/1957. Complementary texts "How to Perform The Balcony" and "Note" published in 1962.

- The Blacks (Les Nègres) 1955/1958/1959 (preface first published in Theatre Complet, Gallimard, 2002)

- Her (Elle) 1955/1989

- The Screens (Les Paravents) 1956-61/1961/1964

- Le Bagne [French edition only] (1994)[8]

Cinema

[edit]- Un chant d'amour (1950)

- Haute Surveillance (1944) was used as the basis for the 1965 American adaptation Deathwatch, directed by Vic Morrow.

- Les Rêves interdits, ou L'autre versant du rêve (Forbidden Dreams or The Other Side of Dreams) (1952) was used as the basis for the script for Tony Richardson's film Mademoiselle, made in 1966.

- Le Bagne (The Penal Colony). Written in the 1950s. Excerpt published in The Selected Writings of Jean Genet, The Ecco Press (1993).

- La Nuit venue/Le Bleu de L'oeil (The Night Has Come/The Blue of the Eye) (1976–78). Excerpts published in Les Nègres au port de la lune, Paris: Editions de la Différence (1988), and in The Cinema of Jean Genet, BFI Publishing (1991).

- "Le Langage de la muraille: cent ans jour après jour" (The Language of the Walls: One Hundred Years Day after Day) (1970s). Unpublished.

- Querelle of Brest (Querelle de Brest) 1947/1953 was used as the basis for the 1982 English-language erotic art film Querelle, directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Poetry

[edit]- Collected in Œuvres complètes (French) and Treasures of the Night: Collected Poems by Jean Genet (English)

- "The Man Sentenced to Death" ("Le Condamné à Mort") (written in 1942, first published in 1945)

- "Funeral March" ("Marche Funebre") (1945)

- "The Galley" ("La Galere") (1945)

- "A Song of Love" ("Un Chant d'Amour") (1946)

- "The Fisherman of the Suquet" ("Le Pecheur du Suquet") (1948)

- "The Parade" ("La Parade") (1948)

- Other

- "Poèmes Retrouvés". First published in Le condamné à mort et autres poèmes suivi de Le funambule, Gallimard

Spitzer, Mark, trans. 2010. The Genet Translations: Poetry and Posthumous Plays. Polemic Press. See www.sptzr.net/genet_translations.htm

- Note

Two of Genet's poems, "The Man Sentenced to Death" and "The Fisherman of the Suquet", were adapted, respectively, as "The Man Condemned to Death" and "The Thief and the Night", and set to music for the album Feasting with Panthers, released in 2011 by Marc Almond and Michael Cashmore. Both poems were adapted and translated by Jeremy Reed.

Essays on art

[edit]- Collected in Fragments et autres textes, 1990 (Fragments of the Artwork, 2003)

- "Jean Cocteau", Bruxelles: Empreintes (1950)

- "Fragments"

- "The Studio of Alberto Giacometti" ("L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti") (1957).

- "The Tightrope Walker" ("Le Funambule").

- "Rembrandt's Secret" ("Le Secret de Rembrandt") (1958). First published in L'Express, September 1958.

- "What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Little Squares All the Same Size and Shot Down the Toilet" ("Ce qui est resté d'un Rembrandt déchiré en petits carrés"). First published in Tel Quel, April 1967.

- "That Strange Word..." ("L'etrange Mot D'.").

Essays on politics

[edit]- Collected in L'Ennemi déclaré: textes et entretiens (1991) – The Declared Enemy (2004)

1960s

- "Interview with Madeleine Gobeil for Playboy", April 1964, pp. 45–55.

- "Lenin's Mistresses" ("Les maîtresses de Lénine"), in Le Nouvel Observateur, n° 185, 30 May 1968.

- "The members of the Assembly" ("Les membres de l'Assemblée nationale"), in Esquire, n° 70, November 1968.

- "A Salute to a Hundred Thousand Stars" ("Un salut aux cent milles étoiles"), in Evergreen Review, December 1968.

- "The Shepherds of Disorder" ("Les Pâtres du désordre"), in Pas à Pas, March 1969, pp. vi–vii.

1970s

- "Yet Another Effort, Frenchman!" ("Français encore un effort"), in L'Idiot international, n° 4, 1970, p. 44.

- "It seems Indecent for Me to Speak of Myself" ("Il me paraît indécent de parler de moi"), Conference, Cambridge, 10 March 1970.

- "Letter to American Intellectuals" ("Lettres aux intellectuels américains"), talk given at the University of Connecticut, 18 March 1970. first published as "Bobby Seale, the Black Panthers and Us White People", in Black Panther Newspaper, 28 March 1970.

- Introduction to George Jackson's book, Soledad Brother, Coward-McCann, New York, 1970.

- May Day Speech, speech at New Haven, 1 mai 1970. San Francisco: City Light Books. Excerpts published as "J'Accuse" in Jeune Afrique, November 1970, and Les Nègres au port de la lune, Paris: Editions de la Différence, 1988.

- "Jean Genet chez les Panthères noires", interview with Michèle Manceau, in Le Nouvel Observateur, n° 289, 25 May 1970.

- "Angela and Her Brothers" ("Angela et ses frères"), in Le Nouvel Observateur, n° 303, 31 août 1970.

- "Angela Davis is in your Clutches" ("Angela Davis est entre vos pattes"), text read 7 October 1970, broadcast on TV in the program L'Invité, 8 November 1970.

- "Pour Georges Jackson", manifesto sent to French artists and intellectuals, July 1971.

- "After the Assassination" ("Après l'assassinat"), written in 1971, published for the first time in 1991 in L'Ennemi déclaré: textes et entretiens.

- "America is Afraid" ("L'Amérique a peur"), in Le Nouvel Observateur, n° 355, 1971. Later published as "The Americans kill off Blacks", in Black Panther Newspaper, 4 September 1971.

- "The Palestinians" ("Les Palestiniens"), Commentary accompanying photographs by Bruno Barbey, published in Zoom, n° 4, 1971.

- "The Black and the Red", in Black Panther Newspaper, 11 September 1971.

- Preface to L'Assassinat de Georges Jackson, published in L'Intolérable, booklet by GIP, Paris, Gallimard, 10 November 1971.

- "Meeting the Guaraní" ("Faites connaissance avec les Guaranis"), in Le Démocrate véronais, 2 juin 1972.

- "On Two or Three books No One Has Ever Talked About" ("Sur deux ou trois livres dont personne n'a jamais parlé"), text read on 2 May 1974, for a radio program on France Culture. Published in L'Humanité as "Jean Genet et la condition des immigrés", 3 May 1974.

- "When 'the worst is certain'" ("Quand 'le pire est toujours sûr'"), written in 1974, published for the first time in 1991 in L'Ennemi déclaré: textes et entretiens.

- "Dying Under Giscard d'Estaing" ("Mourir sous Giscard d'Estaing"), in L'Humanité, 13 May 1974.

- "And Why Not a Fool in Suspenders?" ("Et pourquoi pas la sottise en bretelle?"), in L'Humanité, 25 May 1974.

- "The Women of Jebel Hussein" ("Les Femmes de Djebel Hussein"), in Le Monde diplomatique, 1 July 1974.

- Interview with Hubert Fichte for Die Zeit, n° 8 13 February 1976.

- "The Tenacity of American Blacks" ("La Ténacité des Noirs américains"), in L'Humanité, 16 April 1977.

- "Chartres Cathedral" ("Cathédrale de Chartres, vue cavalière"), in L'Humanité, 30 June 1977.

- "Violence and Britality" ("Violence et brutalité"), in Le Monde, 2 September 1977. Also published as preface to Textes des prisonniers de la Fraction Armée rouge et dernières lettres d'Ulrike Meinhof, Maspero, Cahiers libres, Paris, 1977.

- "Near Ajloun" ("Près d'Ajloun") in Per un Palestine, in a collection of writing in memory of Wael Zouateir, Mazzota, Milan, 1979.

- "Interview with Tahar Ben Jelloun", Le Monde, November 1979.

1980s

- Interview with Antoine Bourseiller (1981) and with Bertrand Poirot-Delpech (1982), distributed as a videocassettes in the series Témoin. Extracts published in Le Monde (1982) and Le Nouvel Observateur (1986).

- "Four Hours in Shatila" ("Quatre heures à Chatila"), in Revue d'études palestiniennes, 1 January 1983.

- Registration No. 1155 (N° Matricule 1155), text written for the catalogue of the exhibition La Rupture, Le Creusot, 1 March 1983.

- Interview with Rudiger Wischenbart and Layla Shahid Barrada for Austrian Radio and the German daily Die Zeit. Published as "Une rencontre avec Jean Genet" in Revue d'études palestiniennes, Autome 1985.

- Interview with Nigel Williams for BBC, 12 November 1985.

- "The Brothers Karamazov" ("Les Frères Karamazov"), in La Nouvelle Revue Française, October 1986.

- Other collected essays

- "The Criminal Child" ("L'Enfant criminel"). Written in 1949, this text was commissioned by RTF (French radio) but was not broadcast due to its controversial nature. It was published in a limited edition in 1949 and later integrated into Volume 5 of Oeuvres Completes.

- Uncollected

- "What I like about the English is that They Are such Liars…", in Sunday Times, 1963, p. 11.

- "Jean Genet chez les Panthères noires", interview with F.-M. Banier, in Le Monde, 23 October 1970.

- "Un appel de M. Jean Genet en faveur des Noirs américains", in Le Monde, 15 October 1970.

- "Jean Genet témoigne pour les Soledad Brothers", in La Nouvelle Critique, June 1971.

- "The Palestinians" (Les Palestiniens), first published as "Shoun Palestine", Beyrouth, 1973. First English version published in Journal of Palestine Studies (Autumn, 1973). First French version ("Genet à Chatila") published by Actes Sud, Arles, 1994.

- "Un héros littéraire: le défunt volubile", in La Nouvelle Critique, juin-juillet 1974 and Europe-Revue littéraire Mensuelle, Numéro spécial Jean Genet, n° 808–809 (1996).

- "Entretien avec Angela Davis", in L'Unité, 23 mai 1975.

- "Des esprits moins charitables que le mien pourraient croire déceler une piètre opération politique", in L'Humanité, 13 août 1975.

- "L'art est le refuge", in Les Nègres au Port de la Lune, Paris: Editions de la Différence, 1988, pp. 99–103.

- "Sainte Hosmose", in Magazine littéraire, Numéro spécial Jean Genet (n° 313), September 1993.

- "Conférence de Stockholm", in L'Infini, n° 51 (1995).

- "La trahison est une aventure spirituelle", in Le Monde, 12 July 1996, p. IV.

- "Ouverture-éclair sur l´Amérique", in Europe-Revue littéraire Mensuelle, Numéro spécial Jean Genet, n° 808–809 (1996).

- "Réponse à un questionnaire", in Europe-Revue littéraire Mensuelle, Numéro spécial Jean Genet, n° 808–809 (1996).

Correspondence

[edit]- Collected in volume

- Lettre à Léonor Fini [Jean Genet's letter, 8 illustrations by Leonor Fini] (1950). Also collected in Fragments et autres textes, 1990 (Fragments of the Artwork, 2003)

- Letters to Roger Blin ("Lettres à Roger Blin", 1966)

- Lettres à Olga et Marc Barbezat (1988)

- Chère Madame, 6 Brife aus Brünn [French and German bilingual edition] (1988). Excerpts reprinted in Genet, by Edmund White.

- Lettres au petit Franz (2000)

- Lettres à Ibis (2010)

- Collected in Théâtre Complet (Editions Gallimard, 2002)

- "Lettre a Jean-Jacques Pauvert", first published as preface to 1954 edition of Les Bonnes. Also in "Fragments et autres textes", 1990 (Fragments of the Artwork, 2003)

- "Lettres à Jean-Louis Barrault"

- "Lettres à Roger Blin"

- "Lettres à Antoine Bourseiller". In Du théâtre no1, July 1993

- "Lettres à Bernard Frechtman"

- "Lettres à Patrice Chéreau"

- Collected in Portrait d'Un Marginal Exemplaire

- "Une lettre de Jean Genet" (to Jacques Derrida), in Les Lettres Françaises, 29 March 1972

- "Lettre à Maurice Toesca", in Cinq Ans de patience, Emile Paul Editeur, 1975.

- "Lettre au professeur Abdelkebir Khatibi", published in Figures de l'etranger, by Abdelkebir Khatibi, 1987.

- "Letter à André Gide", in Essai de Chronologie 1910–1944 by A.Dichy and B.Fouche (1988)

- "Letter to Sartre", in Genet (by Edmund White) (1993)

- "Lettre à Laurent Boyer", in La Nouvelle Revue Francaise, 1996

- "Brouillon de lettre a Vincent Auriel" (first published in Portrait d'Un Marginal Exemplaire

- Uncollected

- "To a Would Be Producer", in Tulane Drama Review, n° 7, 1963, p. 80–81.

- "Lettres à Roger Blin" and "Lettre a Jean-Kouis Barrault et Billets aux comediens", in La Bataille des Paravents, IMEC Editions, 1966

- "Chere Ensemble", published in Les nègres au port de la lune, Paris : Editions de la Différence, 1988.

- "Je ne peux pas le dire", letter to Bernard Frechtman (1960), excerpts published in Libération, 7 April 1988.

- "Letter to Java, Letter to Allen Ginsberg", in Genet (by Edmund White) (1993)

- "Lettre à Carole", in L'Infini, n° 51 (1995)

- "Lettre à Costas Taktsis", published in Europe-Revue littéraire Mensuelle, Numéro spécial Jean Genet, n° 808–809 (1996)

See also

[edit]- Jack Abbott, ex-convict and author, whose works address prison life (among other topics)

- Seth Morgan, ex-convict and novelist, whose book addresses prison life and San Francisco's criminal counterculture

- James Fogle, heroin addict and convict whose only published novel, Drugstore Cowboy, was made into a well known film of the same name

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Contemporary Literary Criticism, Volume 45 By Daniel G. Marowski, Roger Matuz. Gale: 1987 p. 11. ISBN 0-8103-4419-X.

- ^ Brian Gordon Kennelly, Unfinished Business: Tracing Incompletion in Jean Genet's Posthumously Published Plays (Rodopi, 1997) p22

- ^ de Grazia, Edward; Genet, Jean (1993). "An Interview with Jean Genet". Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature. 5 (2): 307–324. doi:10.2307/743530. JSTOR 743530.

- ^ "Jean Genet with Hans Köchler -- Hotel Imperial, Vienna, 6 December 1983". i-p-o.org.

- ^ Kirili, Alain. "Edmund White" Archived 19 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. BOMB Magazine. Spring 1994. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ See Martin Esslin's book for one perspective on Genet's relationship both to Artaud's 'Theatre of Cruelty' and to Esslin's own Theatre of the Absurd. Not all critics agree that Artaud is Genet's most significant influence; both Bertolt Brecht and Luigi Pirandello have also been identified.

- ^ David Bowie & Mick Rock (2005). Moonage Daydream: pp. 140–146

- ^ Spitzer, Mark, trans. 2010. The Genet Translations: Poetry and Posthumous Plays. Polemic Press. See www.sptzr.net/genet_translations.htm.

Sources

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- In English

- Bartlett, Neil, trans. 1995. Splendid's. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-17613-5.

- Bray, Barbara, trans. 1992. Prisoner of Love. By Jean Genet. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

- Frechtman, Bernard, trans. 1960. The Blacks: A Clown Show. By Jean Genet. New York: Grove P. ISBN 0-8021-5028-4.

- ---. 1963a. Our Lady of the Flowers by Jean Genet. London: Paladin, 1998.

- ---. 1963b. The Screens by Jean Genet. London: Faber, 1987. ISBN 0-571-14875-1.

- ---. 1965a. Miracle of the Rose by Jean Genet. London: Blond.

- ---. 1965b. The Thief's Journal by Jean Genet. London: Blond.

- ---. 1966. The Balcony by Jean Genet. Revised edition. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-04595-2.

- ---. 1969. Funeral Rites by Jean Genet. London: Blond. Reprinted in London: Faber and Faber, 1990.

- ---. 1989. The Maids and Deathwatch: Two Plays by Jean Genet. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-14856-5.

- Genet, Jean. 1960. "Note." In Wright and Hands (1991, xiv).

- ---. 1962. "How To Perform The Balcony." In Wright and Hands (1991, xi–xiii).

- ---. 1966. Letters to Roger Blin. In Seaver (1972, 7–60).

- ---. 1967. "What Remained of a Rembrandt Torn Up into Very Even Little Pieces and Chucked into The Crapper." In Seaver (1972, 75–91).

- ---. 1969. "The Strange Word Urb..." In Seaver (1972, 61–74).

- Seaver, Richard, trans. 1972. Reflections on the Theatre and Other Writings by Jean Genet. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-09104-0.

- Spitzer, Mark, trans. 2010. The Genet Translations: Poetry and Posthumous Plays. Polemic Press. See www.sptzr.net/genet_translations.htm

- Streatham, Gregory, trans. 1966. Querelle of Brest by Jean Genet. London: Blond. Reprinted in London: Faber, 2000.

- Wright, Barbara and Terry Hands, trans. 1991. The Balcony by Jean Genet. London and Boston: Faber. ISBN 0-571-15246-5.

- In French

- Individual editions

- Genet, Jean. 1948. Notre Dame des Fleurs. Lyon: Barbezat-L'Arbalète.

- ---. 1949. Journal du voleur. Paris: Gallimard.

- ---. 1951. Miracle de la Rose. Paris: Gallimard.

- ---. 1953a. Pompes Funèbres. Paris: Gallimard.

- ---. 1953b. Querelle de Brest. Paris: Gallimard.

- ---. 1986. Un Captif Amoureux. Paris: Gallimard.

- Complete works

- Genet, Jean. 1952–. Œuvres completes. Paris: Gallimard.

- Volume 1: Saint Genet: comédien et martyr (by J.-P. Sartre)

- Volume 2: Notre-Dame des fleurs – Le condamné à mort – Miracle de la rose – Un chant d'amour

- Volume 3: Pompes funèbres – Le pêcheur du Suquet – Querelle de Brest

- Volume 4: L'étrange mot d' ... – Ce qui est resté d'un Rembrandt déchiré en petits carrés – Le balcon – Les bonnes – Haute surveillance -Lettres à Roger Blin – Comment jouer 'Les bonnes' – Comment jouer 'Le balcon'

- Volume 5: Le funambule – Le secret de Rembrandt – L'atelier d'Alberto Giacometti – Les nègres – Les paravents – L'enfant criminel

- Volume 6: L'ennemi déclaré: textes et entretiens

- ---. 2002. Théâtre Complet. Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

- ---. 2021. Romans et poèmes. Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

Secondary sources

[edit]- In English

- Amin, Kadji. 2017. Disturbing Attachments: Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barber, Stephen. 2004. Jean Genet. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-178-4.

- Choukri, Mohamed. Jean Genet in Tangier. New York: Ecco Press, 1974. SBN 912-94608-3

- Coe, Richard N. 1968. The Vision of Genet. New York: Grove Press.

- Driver, Tom Faw. 1966. Jean Genet. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Frieda Ekotto. 2011. "Race and Sex across the French Atlantic: The Color of Black in Literary, Philosophical, and Theater Discourse." New York: Lexington Press. ISBN 0739141147

- Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz. 1968. Jean Genet. New York: Twayne.

- McMahon, Joseph H. 1963. The Imagination of Jean Genet New Haven: Yale UP.

- Oswald, Laura. 1989. Jean Genet and the Semiotics of Performance. Advances in Semiotics ser. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33152-8.

- Savona, Jeannette L. 1983. Jean Genet. Grove Press Modern Dramatists ser. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-394-62045-3.

- Stephens, Elisabeth. 2009. Queer Writing: Homoeroticism in Jean Genet's Fiction. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0230205857

- Styan, J. L. 1981. Symbolism, Surrealism and the Absurd. Vol. 2 of Modern Drama in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29629-3.

- Webb, Richard C. 1992. File on Genet. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-65530-X.

- White, Edmund. 1993. Genet. Corrected edition. London: Picador, 1994. ISBN 0-330-30622-7.

- Laroche, Hadrien. 2010 The Last Genet: a writer in revolt. Trans David Homel. Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 978-1-55152-365-1.

- Magedera, Ian H. 2014 Outsider Biographies; Savage, de Sade, Wainewright, Ned Kelly, Billy the Kid, Rimbaud and Genet: Base Crime and High Art in Biography and Bio-Fiction, 1744-2000. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3875-2

- In French

- Corrado, Jean-Christophe. Dans les choses plus que les choses. L'imaginaire de Jean Genet, Chêne-Bourg: La Baconnière, 2024.

- Derrida, Jacques.Glas. Galilée, Paris, 1974.

- Ekotto, Frieda. 2001. "L'Ecriture carcérale et le discours juridique: Jean Genet" Paris: L'Harmattan.,

- El Maleh, Edmond Amran. 1988. Jean Genet, Le captif amoureux: et autres essais. Grenoble: Pensée sauvage. ISBN 2-85919-064-3.

- Eribon, Didier. 2001. Une morale du minoritaire: Variations sur un thème de Jean Genet. Paris: Librairie Artème Fayard. ISBN 2-213-60918-7.

- Bougon, Patrice. 1995. Jean Genet, Littérature et politique, L'Esprit Créateur, Spring 1995, Vol. XXXV, N°1

- Hubert, Marie-Claude. 1996. L'esthétique de Jean Genet. Paris: SEDES. ISBN 2-7181-9036-1.

- Jablonka, Ivan. 2004. Les vérités inavouables de Jean Genet. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 2-02-067940-X.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1952. Saint Genet, comédien et martyr. In Jean genet, Oeuvres Complétes de Jean Genet I. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Laroche, Hadrien. 2010. "Le Dernier Genet. Histoire des hommes infâmes". Paris: Champs Flammarion; nouvelle édition, revue et corrigée. ISBN 978-2-0812-4057-5

- Vannouvong, Agnès. 2010. Jean Genet. Les revers du genre. Paris: Les Presses du réel ISBN 978-2-84066-381-2

External links

[edit]- Jean Genet at IMDb

- "Genet, Jean (1910–1986)" From glbtq: Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, & Queer Culture

- William Haver, "The Ontological Priority of Violence: On Several Really Smart Things About Violence in Jean Genet's Work"

- "Jean Genet papers" at the Beinecke Library, Yale University

KSF

KSF