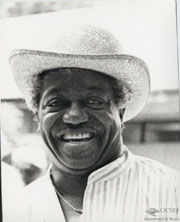

Jimmy Cheatham

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Jimmy Cheatham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Rudolph Cheatham |

| Born | June 18, 1924 Birmingham, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | January 12, 2007 (aged 82) San Diego, California |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation | Musician |

| Instrument | Trombone |

| Years active | 1940s–2000s |

James Rudolph Cheatham (June 18, 1924 – January 12, 2007) was an American jazz trombonist and teacher, who played with Chico Hamilton, Ornette Coleman, Thad Jones, Mel Lewis, Lionel Hampton, Frank Foster, and Duke Ellington.[1][2]

In 1978, Cheatham was invited to lead the jazz program at University of California, San Diego. In 1979 he began to direct the school's African American and jazz performance programs. He retired in 2005.[3]

Biography

[edit]Cheatham was born in Birmingham, Alabama on June 18, 1924,[4][5] the son of Isabelle (née Steen) and Andrew Cheatham,[6][7] who was a conductor on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.[4] After his parents separated when he was a small child, he grew up with his mother and sister, Arlene, in Buffalo, New York.[8][7] In February 1943, he enlisted in the United States Army, and was a member of the 173rd Army Ground Force Band from 1944 to 1946, when he was demobilized following the end of World War II.[3][9] At various times, his colleagues in the band included Eddie Chamblee, Chico Hamilton, Jo Jones, Lester Young, and also Harry White, whom Cheatham said had been "like a mentor" to him.[10]

Taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, Cheatham was able to attend the New York Conservatory of Modern Music in Brooklyn from 1948 to 1950, then from 1950 to 1953 studied at the Westlake College of Music in Los Angeles,[a] where he developed a lifelong friendship with one of his instructors, Russell Garcia.[5][10] While at Westlake, a piece he wrote for string quartet[b] was performed at a concert with Paul Robeson, and he also received a scholarship to the nearby American Operatic Laboratory.[10] Amongst the visitors to the flat he shared with saxophonist Buddy Collette in Los Angeles were Charlie Parker, and the first Gerry Mulligan quartet (including Chico Hamilton) who went there to rehearse.[13]

Cheatham met his wife, Jean Evans, in 1956 in Buffalo, New York, when the local musicians' union chief called them separately to replace two musicians who could not make a job at the local Elks Ballroom. They married in 1959, and their son, Jonathan, was born the same year[14] His wife also had a daughter from a previous relationship, Shirley, who was born in 1951.[15]

During the 1970s, Cheatham taught jazz at Bennington College in Vermont, and also at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin.[16]

In 1984, Cheatham and his wife won a bronze medal at the New York Festivals Film and TV Awards for the 1983 KPBS television special Three Generations of the Blues, which featured Sippie Wallace, Big Mama Thornton, and Jennie Cheatham.[17]

Also in 1984, the Cheathams formed the Sweet Baby Blues Band,[18] reviving Kansas City-style blues.[19] The first of the eight studio albums they released between 1985 and 1996, Sweet Baby Blues, was the sole recording to receive a Grand Prix du Disque de Jazz[c] from the Hot Club de France in 1985.[20][21] Their fifth album, Luv in the Afternoon (1990), was also voted amongst the best blues albums of the year in Down Beat magazine's 39th annual poll of international music critics, as published in 1991.[22] In 1998, the band was described as "an earthy jump blues combo that plays funky, hard-swinging, boogie-busting music".[23]

Cheatham's legacy is carried on by several students who went on to become, like him, prominent composer/performer/educators: flutist Nicole Mitchell,[24] bassist Karl E. H. Seigfried, and drummer Vikas Srivastava.

Cheatham died in San Diego, California on January 12, 2007, aged 82, having undergone heart surgery the previous month.[25]

Discography

[edit]As co-leader

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Sweet Baby Blues (1985) – Note: includes the Cheatham's signature song, "Meet Me With Your Black Drawers On".[26]

Jeannie Cheatham and Jimmy Cheatham

with Red Callender, John "Ironman" Harris, Charles McPherson, Jimmy Noone, Curtis Peagler, Snooky Young

Concord Jazz

CCD-4258 (CD) CJ-258 (LP) CJC-258 (MC)

- Midnight Mama (1986)[26]

Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4297 (CD) CJ-297 (LP) CJ 297-C (MC)

- Homeward Bound (1987)[26]

Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4321 (CD) CJ-321 (LP) CJ 321-C (MC)

- Back to the Neighborhood (1989)[26]

Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4373 (CD) CJ-373 (LP) CJ 373-C (MC)

- Luv in the Afternoon (1990)[26]

Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4429 (CD)

- Basket Full of Blues (1992)[26]

Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4501 (CD) CJ 501-C (MC)

- Blues and the Boogie Masters (1993)[23]

Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4579 (CD)

- Gud Nuz Bluz (1996)[23]

Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham and the Sweet Baby Blues Band

Concord Jazz

CCD-4690 (CD)

Compilation albums

[edit]- The Concord Jazz Heritage Series: Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham (1998)[27]

Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham

Concord Jazz

CCD-4837 (CD)

As sideman

[edit]With Bill Dixon

- Intents and Purposes (RCA Victor, 1967)[28]

With Chico Hamilton

- El Chico (Impulse!, 1965)[29]

- The Further Adventures of El Chico (Impulse!, 1966)[29]

- The Dealer (Impulse!, 1966)[d]

- The Gamut (Solid State, 1968)[29]

- Juniflip (Joyous Shout, 2006)[31]

With Grover Mitchell

Notes

[edit]- ^ Opened in 1945, Westlake College was only the second institution in the United States to offer a university-level jazz program, after Schillinger House in Boston. It closed in 1961.[11]

- ^ It is unclear if this referred to Menorah, a work for flute quartet composed by (a) James Cheatham, which was played at a 1953 concert in Los Angeles involving Elmer Bernstein.[12]

- ^ This should not be confused with the Grand Prix du Disque Jazz, awarded by the Académie Charles Cros.

- ^ Cheatham arranged two tracks on the album and conducted a third, but played (uncredited) percussion only. The final track on the original LP release, "Jim-Jeannie", was named after the Cheathams.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Voce, Steve (January 20, 2007). "Jimmy Cheatham: Sweet Baby Blues Trombonist". The Independent. No. 6322. London. pp. 46–47. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Eagle, Bob & LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. p. 256. ISBN 9780313344237.

- ^ a b Cheatham, Jimmy & Tregaser, Jim (May 2020). "Enlistment Blues: How I joined the Army, met Lester Young and Jo Jones, and found a career in jazz (Part One)". San Diego Troubadour. San Diego, CA. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Dance, Stanley (1987). "Jimmy Cheatham". Jazz Journal International. Vol. 40, no. 9. London: Jazz Journal Ltd. pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b Rye, Howard (2002). "Cheatham, Jimmy (James Rudolph)". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.J733900. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Cheatham, Jeannie (2006). Meet Me with Your Black Drawers On: My Life in Music. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780292712935. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "United States Census, 1940: James Cheatham in Household of Isabelle Cheatham, Ward 5, Buffalo, Buffalo City, Erie, New York, United States (Roll 2825, ED 64-85, Sheet 61A, Line 27)". Washington DC: National Archives and Records Administration. 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ Cheatham (2006), p. 177.

- ^ Cheatham, Jimmy & Tregaser, Jim (June 2020). "Enlistment Blues: How I joined the Army, met Lester Young and Jo Jones, and found a career in jazz (Part Two)". San Diego Troubadour. San Diego, CA. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Cheatham, Jimmy & Tregaser, Jim (July 2020). "Enlistment Blues: How I joined the Army, met Lester Young and Jo Jones, and found a career in jazz (Part Three)". San Diego Troubadour. San Diego, CA. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Spencer, Michael T. (2013). "Jazz Education at the Westlake College of Music, 1945–61". Journal of Historical Research in Music Education. 35 (1). Sage Publications: 50–65. doi:10.1177/153660061303500105. ISSN 1536-6006. JSTOR 43958416. S2CID 140361507. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Humanists Plan History Program For This Sunday". The California Eagle. Vol. 72, no. 46. Los Angeles: Loren Miller. February 12, 1953. p. 2. Retrieved January 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vacher, Peter (March 28, 2007). "Jimmy Cheatham: Trombonist fusing jazz and blues". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Cheatham (2006), p. 174.

- ^ Cheatham (2006), pp. 113–115.

- ^ Mendoza, Bart (2007). "Jimmy & Jeannie Cheatham: A Life of Music, Joy, & Inspiration" (PDF). San Diego Troubadour. Vol. 6, no. 5. La Jolia, CA. pp. 8–9. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Honours & Awards" (PDF). Bear Facts. Vol. 22, no. 6. San Diego, CA: Oceanids, University of California, San Diego. 1984. p. 15. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Cheatham (2006), p. 311.

- ^ "The Kansas City Style: A Marriage of Blues & Jazz". San Diego, CA: The Library, University of California San Diego. January 20, 2015. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Cheatham (2006), p. 364.

- ^ "Prix du disque de jazz décernés par le Hot Club de France de 1936 à 1992" [Jazz recording awards presented by the Hot Club of France from 1936 to 1992]. Hot Club de France (in French). Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Ephland, John (1991). "Down Beat's 39th Annual International Critics Poll" (PDF). Down Beat. Vol. 58, no. 8. Elmhurst, IL: Mahler Publications. pp. 20–24. ISSN 0012-5768. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Gilbert, Andrew (1998). "Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham & the Sweet Baby Blues Band". In Holtje, Steve & Lee, Nancy Ann (eds.). MusicHound Jazz: The Essential Album Guide. New York: Schirmer Trade Books. pp. 223–224. ISBN 1578590310. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Varga, George & Mitchell, Nicole (April 25, 2019). "Before & After with Nicole Mitchell". JazzTimes. Braintree, MA. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Moe, Doug (March 21, 2007). "A memorial for Jimmy Cheatham". The Capital Times (Home Final ed.). Madison, WI. p. A2. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Lord, Tom (1992). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 4. West Vancouver, BC & Redwood, NY: Lord Music Reference & Clarence Jazz Books. pp. C276 – C277. ISBN 1881993035. OCLC 1035901586. Retrieved January 13, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Jeannie & Jimmy Cheatham". Discogs. Portland, OR: Zink Media. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Lord, Tom (1993). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 5. West Vancouver, BC & Redwood, NY: Lord Music Reference & Clarence Jazz Books. p. D360. ISBN 1881993043. OCLC 1035903524. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Lord, Tom (1994). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 8. West Vancouver, BC & Redwood, NY: Lord Music Reference & Clarence Jazz Books. p. H85. ISBN 1881993078. OCLC 1035920133. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Cook, Richard & Morton, Brian (2006). "Chico Hamilton". The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings (Eighth ed.). London: Penguin. pp. 574–575. ISBN 9780141023274. OCLC 1245637586. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Chico Hamilton – Juniflip". Discogs. Portland, OR: Zink Media. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Lord, Tom (1996). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 15. West Vancouver, BC & Redwood, NY: Lord Music Reference & Clarence Jazz Books. p. M930. ISBN 1881993140. OCLC 1035901585. Retrieved January 14, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

KSF

KSF