Joel Gascoyne

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

Joel Gascoyne (bap. 1650—c. 1704) was an English nautical chartmaker, land cartographer and surveyor who set new standards of accuracy and pioneered large scale county maps. After achieving repute in the Thames school of chartmakers, he switched careers and became one of the leading surveyors of his day and a maker of land maps. He is best known for his maps of the colonial Province of Carolina, of the county of Cornwall, and the early 18th-century Parish of Stepney, precursor of today's East End of London. Gascoyne's distinctive style of chart and map-drawing was characterised by the use of bold and imaginative cartouches.

Origins

[edit]Born into a seafaring family prominent in the port of Hull, Yorkshire, Joel Gascoyne was baptised at Holy Trinity Church on 31 October 1650. His father Thomas was a sea captain. At 18 Gascoyne was apprenticed for seven years to John Thornton, citizen and draper of London, a leading member of the Thames chartmakers.[1]

The Thames school of chartmakers

[edit]The Thames school of chartmakers was a small group who plied their trade in streets and alleys leading down to the waterfront on the north Bank of the Thames, east of the Tower of London.[1] Active between 1590 and 1740,[2] they were critically involved in England's maritime affairs, yet the school was not identified by modern scholars until 1959.

Joel Gascoyne, master chartmaker

[edit]In 1675 Gascoyne set up in business for himself at "Ye Signe of ye Platt neare Wapping Old Stayres three doares below ye Chapell" (arrow), taking apprentices of his own and producing manuscript and engraved charts.[1]

Nautical charts in Gascoyne's era - when accurate maritime clocks did not exist and mariners could not determine geographical longitude - were conceptually different from modern charts. It is explained in the article windrose network.

Gascoyne acquired such fame that his counsel was twice sought by administrator of the Navy Samuel Pepys and his services were commissioned by the proprietors of the colony of Carolina.[3]

Amongst Gascoyne's early works were four engraved Mediterranean charts published in John Seller's English Pilot (1677).[4]

In 1678 Gascoyne drew on vellum for Captain John Smith a coloured portolan chart[5] pasted on four hinged oak boards; the western half survives at the National Maritime Museum Greenwich. Coming to the attention of the Lords Proprietors of the province of Carolina, he was commissioned to engrave a map of their province (1682) from the latest surveys;[5] their intention was to attract immigrants to the new colony.[6]

The Mediterranean

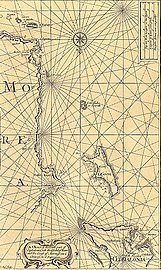

[edit]From Seller's The English Pilot (David Rumsey Map Collection).

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

- "A chart of the Straits of Gibralter", complete with tide-tables

- "A chart of Corfu, Pachsu and Antipachsu with the Channel & roads between the Island of Corfu & Graetian coast"

- "A chart of the south part of Cephalonia, with the Islands of Zante, and the coast of Morea from C. Chiarese, to C. Sapienza"

- "A chart of the south coast of Morea from Venetica to C.S. Angelo with ye islands of Serigo, Serigoto and part of Candia"

America

[edit]-

1

-

2

- Western Atlantic. "Made By Joel Gascoyne at ye Signe of the Platt at Waping old Stayres Ano Dom: 1678 For Capt. John Smith", showing the Eastern Coast of North America from Newfoundland to Mexico, with Central America, the West Indies and the Northern Part of South America. (National Maritime Museum.) Notice the plattboard hinge-line.

- "A new map of the country of Carolina with its rivers, harbors, plantations and other accomodations don from the latest surveighs and best information by order of the Lords Proprietors". (John Carter Brown Library.) North is to the right. The inset shows Charleston Harbor. "No more careful or accurate printed map of the province of Carolina as a whole was to appear until well into the eighteenth century",[7] though Gascoyne did not survey the territory in person.

The East

[edit]-

1

-

2

-

3

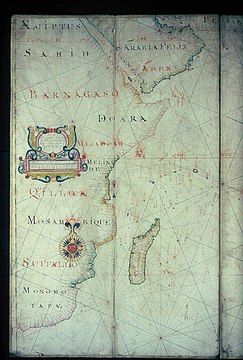

- Indian Ocean off Mozambique and Madagascar, from the second part of the Oriental Navigation (Bodleian Libraries)

- Indian Ocean, south of India, Siam and Sumatra , from the second part of the Oriental Navigation (Bodleian Libraries)

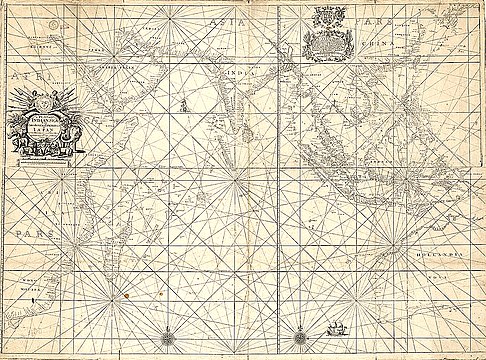

- "A plat of the Indian sea from Cabo Bonea Esperanca (Cape of Good Hope) to Iapan" (Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France: monochrome reproduction). "This rare and splendid undated chart" was made in collaboration with his old master John Thornton.[8]

The English revolution; career change

[edit]

Increasing competition from printed charts squeezed profits in the chart industry.[5]

In October 1688 died Gascoyne's influential patron the Duke of Albemarle, governor of Jamaica, leaving Gascoyne at a disadvantage.[9]

On 11 December, King James II fled London when popular support for his government collapsed, ushering in the Glorious Revolution.

The next day, just a few yards[10] from Gascoyne's shop at Wapping Old Stairs, a vengeful crowd seized Judge Jeffreys, who was trying to flee the country in disguise;[11] Jeffreys was taken into protective custody.

In 1689 Gascoyne ceased to be an active member of the Drapers Company and took up land surveying.[9] The pursuit of this new career sometimes gave him the collateral opportunity to make large scale maps.

Estate surveyor

[edit]

In 1692 Gascoyne was engaged to map Sayes Court, Deptford, the property of diarist John Evelyn. It was a prestigious commission, for in matters of gardening Evelyn was a trendsetter for country gentlemen, and at Sayes Court he created a beautiful home and garden.

The next year the revolutionary government of William and Mary directed Gascoyne to survey the manor of Greenwich preparatory to instituting a home for retired sailors: Greenwich Hospital. Thus Gascoyne had established himself as one of the leading land-surveyors of the day.[12]

For the next six years he was away in Cornwall (see below), but on his return he was commissioned to survey several estates, including Enfield Chase and the manor of Great Hasely.[13]

Land surveying in Gascoyne's day

[edit]The instruments and techniques available to Gascoyne were rudimentary by today's standards. Theodolite-type instruments of his time used pointers, somewhat like the sights used on firearms; sighting telescopes with crosshairs, though invented, were not in use.[14] Hence, angle measuremens were not very accurate.[15] A standard textbook of Gascoyne's day asserted that

there is no Man, with the best instrument that was every yet made, can take an Angle in the Field nigher, if so nigh, as to Five Minutes [5 minutes of arc]

which to a modern surveyor seemed incredibly bad.[14] Measuring chains were not corrected for temperature. For longer distances a measuring wheel called a perambulator (see illustration) was used.

Estate surveyors were disliked by farmers and tenants, who might refuse them access, wrote Eva Taylor:

This was partly because they feared that their holdings would prove larger than the old written records indicated, with a consequent raising of the rent, or more generally that 'concealed lands' would be revealed... Among the ignorant, however, there was a superstitious fear of the man who could 'measure at a distance', since this appeared to be a species of conjuring or black magic.[16]

The Cornish maps

[edit]Though there is no direct historical record of it, map historian William Ravenhill showed that in 1693 Gascoyne was lured to Cornwall to survey the landholdings of two powerful families: those of John Grenville, first Earl of Bath, and Charles Robartes, second Earl of Radnor. Grenville had fought for the Royalists in the English Civil War, accompanying the future Charles II into exile; the Robartes family had fought for the Parliamentarians.

-

John Grenville

-

Charles Robartes

-

Lanhydrock House before the Victorian alterations

The Grenvilles had been Lords of the Manors of Kilkhampton and Bideford since the 11th century. Their seat was at Stowe House, which Grenville had rebuilt on a magnificent scale. He now wanted a surveyor to measure and plot his whole estate. Grenville had political connections with the colonial proprietors of Carolina and must have been familiar with Gascoyne's map of that country.[17]

In contrast, the Robartes had made their fortune in trade, originally by selling furze to tin miners — for fuel. They got their first peerage by paying a £10,000 bribe to the Duke of Buckingham (though they protested it was extortion).[18] They invested their trading profits in moneylending at high rates of interest, taking mortgages as security. When the borrowers defaulted, the Robartes foreclosed and took possession. Thus their landholdings, though amounting to 40,000 acres,[19] were scattered all over Cornwall.[20] The Robartes' seat was Lanhydrock House. Charles Robartes had boundary disputes with other Cornish landowners, who accused him of landgrabbing. He needed to survey his many and scattered estates.[21]

It gave Gascoyne the collateral opportunity to survey all over the county, hence to make his great one-inch map on his own account.[20]

The one-inch map of the county of Cornwall

[edit]

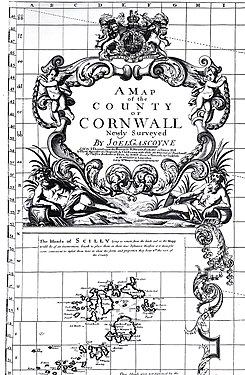

On March 27, 1699, Gascoyne issued a broadsheet addressed to the nobility and gentry of the county of Cornwall inviting them to subscribe to his map, which was nearly finished.[22]

His map is on a scale of very nearly one inch to the mile, unprecedented for the era, and not equalled by the Ordnance Survey until their Kent map of 1801. Gascoyne's map measures about 6 by 4+1⁄2 feet (1.8 m × 1.4 m) when mounted.[23] Into this space he mapped a mass of detail:

I have laid down as many of the Villages and Cottages, with other Remarkable Places, as so Narrow a Compass will admit, without making it burthensom to the Eye.[24]

In "Joel Gascoyne, a Pioneer of Large-Scale County Mapping", William Ravenhill said that Cornwall was the first[25] county to be mapped on a large scale. Even 50 years later, only a handful had been.[5]

Accuracy

[edit]When tested with a modern Ordnance Survey map, the accuracy of Gascoyne's interpoint distances is so consistently good[26] as to be surprising. How he managed to achieve such field measurements with the instruments of his day has not been explained. He must, at least, have used a system of carefully surveyed triangles, a procedure that was not standard until the late 18th century.[27]

His map includes lines of latitude and their graduations (longitude he prudently[28] omitted ). These, however, contain a curious systematic error. While fairly accurate near the Lizard,[29] the values tend to be overstated the further one goes north — so consistently as to suggest the map-maker was erroneously taking the length of a minute of arc to be a statute mile, instead of a geographical mile as it really is.[30] Ravenhill suspected the fault lay with John Harris the engraver, who would have added the latitude and grid lines afterwards.[31]

Format

[edit]An innovation was the mapping of parish boundaries. Parishes were local government units, hence it was important to know the limits of their jurisdiction. Gascoyne mapped 201 parishes. Observed Professor Ravenhill:

By any standards of the time mapping in such detail was an outstanding achievement. Incidentally, the Ordnance Survey did not manage to put parish boundaries on their one-inch maps until the middle of the nineteenth century.

The printed gazetteer lists 2,475 placenames, mostly classified by parish, and with grid references.[32]

-

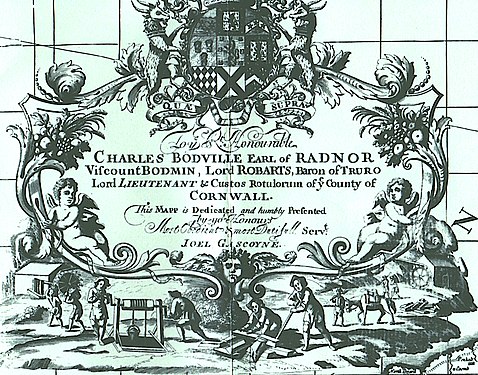

Cartouche and (inset) the Isles of Scilly

-

Dedication to his patron Charles Robartes, replete with iconography of the tin-mining industry

-

A portion of Gascoyne's map showing the Lizard (bottom), Truro (top right) and Mounts Bay (left)

Gentlemen who subscribed could have their names engraved under their family seats; 98 did so.[33]

Production

[edit]Gascoyne's map was printed from seven engraved copper plates, plus six pages of letterpress for the gazetteer of placenames. A finished map would consist of six rectangular sheets mounted on cloth.[34]

The copper plate process was laborious. Large copper sheets were difficult to obtain.[35] After engraving a sheet, which was done in 'mirror' writing with a sharp steel rod called a burin, it was heated and very carefully[36] inked, then put through a rolling press — which worked on the mangle principle — together with a damp sheet of paper at great pressure.[37] Optionally, patrons could have the map coloured by hand,[38] for which an additional charge was customary.[39]

Modern re-publication

[edit]In 1991 the Devon and Cornwall Record Society published a facsimile edition of Gascoyne's map. By this time only three copies of the original map could be found, two of them in museums but in unsuitable condition, the third privately owned by a Cornish architect, who loaned it to the publishers. The production comes in a boxed set with 12 map sheets on the original scale, a key map on a reduced scale, and scholarly commentaries.[38]

The Stowe and Lanhydrock atlases

[edit]

The Stowe Atlas is a survey of the Grenville properties. "Beautiful", it comprises 33 hand-drawn maps on vellum, bound in a black leather volume, tooled in gold.[20] For a long time the Stowe Atlas was unknown to historians, but it reappeared in the 20th century and is now in Kresen Kernow the Cornish public archives.[40]

The Lanhydrock Atlas is a survey of the Robartes properties. It comprises four large volumes, bound in leather, containing 258 manuscript maps on vellum.[41] In 2010 a one-volume edition — with all the maps plus scholarly commentaries — was published on behalf of the National Trust.[42]

Because the maps in both atlases, though fairly obviously by the same author, are unsigned, they were thought to be the work of a local Cornish surveyor.[19] However, William Ravenhill, the historian of cartography who deeply studied the maps of Gascoyne, made the correct attribution. Not only were the place-names too Anglicised for a Cornishman, the elaborate compass roses[43] and colourful cartouches[44] were typical of Joel Gascoyne's work, as was the maritime[45] flavour. Furthermore, by paying attention to Gascoyne's known patrons, Professor Ravenhill was able to suggest why Gascoyne came to be working for Grenville and Robartes in the first place, a fact which had not been suspected.[46][47]

Writing of the Lanhydrock Atlas, Fiona Reynolds said:

In the three hundred years since Joel Gascoyne's death, surveying and mapping have developed beyond comprehension. Yet, today, in this age of computer and satellite technologies, we still marvel at his achievement, wondering at the sheer quality and aesthetic beauty of the maps...[48]

while Oliver Padel said:

The plans are astonishingly accurate, and the field boundaries nearly always correspond very closely to those shown on the large-scale maps of the late nineteenth and earlier twentieth century, even in very minor details.[49]

The parish of St Dunstan Stepney, the incipient East End of London

[edit]

Significance

[edit]The population booms of the 19th and early 20th centuries made the East End of London a byword for overcrowding and overbuilding. Despite this, much of its earlier history can be recovered thanks to Gascoyne's splendid[51] maps of the area.

The area: the need for a map

[edit]The medieval parish of St Dunstan's, Stepney was an area of 7 square miles lying between the wall of the City of London and the River Lea to the east, where Essex began. It was mostly open fields or marshland. In Gascoyne's day it was still largely intact, though four settlements had been hived off and given independent status.[52] It was still predominately farmland, except up against the City, where it was "pestered" by houses, often illegally built,[53] and along the densely built river front — London's rapidly growing maritime area, known as Sailor Town. By the end of the 19th century the area would have a million people and be better known as the East End of London.

Hence by 1700 the parish needed to be surveyed for practical purposes. The local government, known as the Vestry,[54] was responsible for a host of functions — the relief of poverty, highways, law and order, vagrants, the oversight of charities — and the collection of taxes to pay for these things. Taxes were levied on land occupation. In 1702 they decided to commission "some skilful Geographer or Plattmaker" to map the parish, its hamlets and their boundaries. They chose Joel Gascoyne.[55]

The challenge

[edit]John Strype writing thirteen years later described Stepney as "rather a Province than a Parish",

especially if we add, that it contains in it both City and Country: For towards the South Parts, where it lies along the River Thames for a great way, by Limehouse Poplar, and Radcliff, to Wappin, it is furnished with every thing that may intitle it to the Honour (if not of a City, yet) of a great Town; Populousness, Traffick, Commerce, Havens, Shipping, Manufacture, Plenty and Wealth, the Crown of all... On the other Side, Northward, this Parish hath the face of a Country, affording every thing to render it pleasant, Fields, Pasture-Grounds for Cattle, and formerly Woods and Marshes.[56]

While the parish of Stepney was much smaller (and flatter) than Cornwall, the map was to be on a bigger scale (1:5,550, or about 11 inches to the mile), and had to depict fine urban detail, because its fiscal purpose was to show tax-liable properties, such as fields, terraces and stand-alone houses, and even courts and alleys.

Professor Ravenhill, who wrote an introduction to a modern edition of Gascoyne's map, referred to the danger of surveying in "the often squalid and congested purlieus of late seventeenth-century London where the welcome accorded to seemingly inquisitive surveyors could have been anything but warm and co-operative. It is in the surveying of the detail of these courts and alleys that Joel Gascoyne would have met his most testing problems..."[57]

The parish contained 9 or 10 scattered hamlets, known as the Tower hamlets (because, originally, they had had a feudal obligation to supply men to guard the Tower of London).[58] From London, two ancient main roads ran across the parish:

- the highway running northeast to Colchester and Harwich (including the Mile End Road);

- the coastal highway running east to Limehouse (including the Ratcliff Highway).

Ribbon development along these routes accounted for most of the housing.

Apart from his main map of the parish, Gascoyne was independently commissioned to map three individual hamlets: Limehouse, Mile End Old Town, and Bethnal Green.

The Limehouse map was on a scale of 1:2,376, or nearly 27 inches to the mile.[59] By way of comparison, the Ordnance Survey did not survey an English town until 1843, and did not make 25-inch maps of any part of the country until 1853.[60]

Joel Gascoyne's Stepney

[edit]Some fragments of Gascoyne's vanishing Stepney lasted long enough to be captured by artists, or even to survive to this day. These buildings can be found on his maps.[61]

The centre

[edit]In the middle of the parish, standing in cow-grazed fields, was the church. Founded in Anglo-Saxon times, it was dedicated to St Dunstan, who was Bishop of London in AD 958. High-status individuals had country estates in early Stepney and a number are buried im its churchyard, as are many sea captains.[62] For some reason it acquired a reputation for facetious epitaphs; for example—

EPITAPHHere Thomas Saffin lies interr'd, ah why?

Born in New England, did in London die.

EPITAPHHere lies the body of Daniel Saul

Spitalfields weaver, and that's all.[63]

Known as the Church of the High Seas, it had a strong maritime connection; legal textbooks said "A British man-of-war is, by a legal fiction, always a part of the parish of Stepney".[64] Its bells feature in the children's song Oranges and Lemons.

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

- The parish church as it would have looked in Gascoyne's day (George Shepherd: British Museum)

- Memorial for an Elizabethan sea captain and his wife (interior)

- St Dunstan's today.

- "King John's Court", in fact a surviving medieval moated manor house By Gascoyne's day it had passed into the hands of radical religious dissenters. (Engraving by "Antiquity" Smith, 1791: British Museum). Demolished 1810,[65] recently excavated for Crossrail at the City Farm site.

- Colet's house in Stepney (anonymous print: British Museum). Dean Colet, Renaissance humanist, friend of Erasmus and St Thomas More, was a vicar of St Dunstan's. The drawing shows the house in about 1815.

- A William and Mary house, 37 Stepney Green, E1. Built in 1694[66] or a little earlier,[67] "it is one of the finest in the entire borough, and a rare example of a large, formerly free-standing 17th-century house in inner London.[68]

This specimen shows that Gascoyne depicts every individual field, with the name of its owner (i.e. the taxpayer). Where space does not permit him to name a significant feature, he uses a numeral referenced to a table.

The arrow indicates the parish church. It had both a rector and a vicar. The rectory is depicted as a row of gables just to the east of the church.[69]

The road running northwest from the church ("Mile End Green") is today Stepney Green.

"King John's Court" is a little way up this road, marked '2' by Gascoyne (requires magnification).

No. 37 Stepney Green is about three-quarters of the way up the road, under the word 'Nicolson'.

Dean Colet's house is marked "Belonging to Paul School" (which he founded).

Nearly opposite to that, also marked "2", is "the Mercers Almes Houses"

The numerous bowling greens reflect the leisure character of the area. An "astonishing" number of houses in Mile End Town, a little to the north, were licensed to sell liquor. But, in general, the neighbourhood was a retirement village, inhabited by "rich Citizens and Sea-Captains".[70]

Mile End Old Town was noted for its numerous almshouses.[71] The charitable use of the area is further shown by the field for the support of "Poor of Criplegate";and, to its left, numeral "9", denoting "Jews' Burial Place".

Spitalfields and Mile End

[edit]-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7

-

8

- Silk weaver's house, Folgate Street, Spitalfields, now a museum. Many Huguenots escaping religious persecution were silk weavers, and came to live in Spitalfields, just outside the jurisdiction[72] of the City trade guilds.

- Huguenot preacher: Jacques Misaubin (left) was pastor of a French church in Spitalfields — the only locality in England where French was spoken in the streets. (Welcome Collection).

- 23 Fournier Street. Notice the weavers' loft with its characteristic skylight.

- 4 Princelet Street, Spitalfields.

- Trinity Green Almshouses, Mile End Road, built for sea captains and their widows who had fallen on hard times. A Grade I listed building, the Survey of London attributes it to Sir Christopher Wren and John Evelyn jointly — with a suggestion that Joel Gascoyne might have been involved too.[73]

- Early wooden houses in the Mile End Road, still standing in this 1899 photo (Historic England), but demolished in 1902 to make way for Stepney Green tube station.

- 107 Mile End Road

- Jewish inscription (1684) on a tablet, north wall of the Velho[74] burial ground for Portuguese Jews, Mile End Road (Historic England). The plaque survives in its place to this day. The inscription may be an early instance of a public text in Judaeo-Spanish written in Latin characters. Oliver Cromwell had encouraged Jews to return to England when Joel Gascoyne was a boy.

A. Another extract from Gascoyne's map of the parish of Stepney, showing the built up area of Spitalfields. Building near to London was theoretically illegal, so unauthorised dwellings were hidden away in back gardens or courts. Into these tightly packed habitations French (and other) refugees crowded.

Despite this, "[Gascoyne's] blocks are not mere diagrams but real houses", wrote David Johnson. The arrow indicates Spitalfields Market with its central cruciform building surrounded by market stalls "carefully individualised by Gascoyne".[75]

B. Cartouche from Gascoyne's map of Mile End Old Town, which the hamlet commissioned separately. The symbolism concerns the hamlet's interest in dairy pasturage. The arrow indicates a curious local feature, Whitechapel Mount.

"Sailor Town"

[edit]Running due east from the Tower of London was the Ratcliff Highway, a coastal route originating in Roman times. Cutting across a peninsula to avoid the marshlands of Wapping, it rejoined the Thames at the gravel outcrop of Ratcliff. By Gascoyne's day the marsh had been reclaimed as gardens and his map shows Ratcliff with three shipyards. The route continued east under other names, going through Limehouse, cutting across the neck of the Isle of Dogs at Poplar, and ending at Blackwall Yard where East Indiamen were built. Ribbon development along much of this route produced a densely settled maritime population.[76]

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

- Pelican Stairs, Wapping and the Prospect of Whitby

- Wapping Old Stairs, next to Gascoyne'a old platt shop

- Figures at St John Schools, Scandrett Street

- Riverside terrace, in what is now[77] called Narrow Street, Limehouse.

- The same properties viewed from the Thames (German print, about 1735: British Museum). The properties are located after the first indentation on the left, which was a dry dock known as Limehouse Bridge Dock, because crossed by a drawbridge.[78]

- Limehouse Barge Builders by Charles Napier Hemy, showing the scene in about 1880. Waterfront buildings were valuable commercial property; owners, untroubled by planning laws, jerry built to suit.[79] (South Shields Museum and Art Gallery.)

Further river settlements

[edit]-

1

-

2

-

3

- Ratcliff was the quintessential Sailor Town. A crowded waterfront and an important maritime centre since Tudor times, most of it was destroyed by fire in 1794; therefore no houses from Gascoyne's time have survived. This image shows one that did escape the fire. Seemingly, in Gascoyne's youth, Ratcliff was a retirement destination for pirates of the Caribbean: some of these were immensely rich.[80]

- Isle of Dogs by Robert Dodd (detail). This picture, though painted later, shows the southern tip of the peninsula as it was Gascoyne's time: cattle-raising land, well below high water mark, precariously defended by a 15-foot river wall. The people are waiting for the ferry. (National Maritime Museum.) The Isle of Dogs (known as Stepney Marshes) was famous for its rich grazing and fat cattle and sheep. Gascoyne's map of the area shows seven windmills with their owner's names.[81]

- Blackwall, dominated by the East India Company, whose ships were built in, repaired and victualled at Blackwall Yard.[82]

Re-publication

[edit]In 1995 the London Topographical Society published a facsimile of Gascoyne's four[83] maps in eight large sheets in a looseleaf folder,[84] together with learned commentaries by William Ravenhill and David Johnson; the folder of maps and the commentaries are now sold separately. A reduced version of the main map had been published by John Strype in 1755, and again by Stepney Parish in 1890.[85]

The cartouches of Joel Gascoyne

[edit]After 300 years Gascoyne's surviving charts and maps are not necessarily in perfect condition, and high-resolution images are not always available. Even so, his characteristic style of cartouche-making can be examined.

A cartouche was usually placed above or around the scale, and was a limited area wherein the cartographer was not only free, but expected to display his talent for decoration. Gascoyne's work was characterised by bold and imaginative cartouches which became a kind of trademark.[86] Map historian William Ravenhill called him a cartographer with style.[87]

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

- From his printed "map of the straits of Gibralter" (1677), one of his earliest works. Unusually, the scale is placed at an angle, sustained by Neptune's trident.

- From his "the second part of the Oriental Navigation" (1684), "made by Joel Gascoyne at the Sign of ye Platt nere Wapping old Staires 3 doares down from ye Chappell"

- From his chart of the West Atlantic "made for Capn John Smith (1678)

- From his map of the hamlet of Bethnal Green. Printed maps were monochrome but clients paid to have them hand-coloured (as here). The legend of the blind beggar (a mighty knight who loses his eyesight in battle and must subsist as a beggar in Bethnal Green) had a powerful appeal in the district.

Death

[edit]

When Gascoyne negotiated with the Vestry of St Dunstan Stepney in 1702, he could see a prominent inscribed stone in the church, the image of which is reproduced here. In less than three years, Joel Gascoyne was dead.

Almost nothing is known about his personal life, except that he was married to one Elizabeth and that she, living in Barking, applied for letters of administration of his estate on 13 February 1705.[88][89]

References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Maeer 2020, p. 68.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, pp. 61, 60.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, pp. 60, 70 n.12.

- ^ a b c d Ravenhill 1972b, p. 60.

- ^ Duff 1998, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Duff 1998, p. 58, quoting Cumming, The Southeast in Early Maps

- ^ Roncière 1965, p. 46.

- ^ a b Ravenhill 1972b, p. 61.

- ^ His premises at Wapping Old Stairs, three doors down from St John's Church, were adjacent to a public house (today called the Town of Ramsgate), which still exists, and where Jeffreys was lurking.

- ^ London Gazette 1688, p. 2.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ravenhill 1974.

- ^ a b Bowie 1929, pp. 402–3.

- ^ Merdinger 1954, p. 206.

- ^ Taylor 1947, pp. 130–1.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, pp. 64, 66.

- ^ Mayes 1957, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Pounds 1945, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Ravenhill 1972b, p. 66.

- ^ Holden, Herring & Padel 2010, pp. 14, 16.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, p. 65.

- ^ Gascoyne, Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. vi.

- ^ Gascoyne, Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. 13.

- ^ Apart from the minuscule county of Rutland: Ravenhill 1972b, p. 60 n.1.

- ^ Professor Ravenhill calculated a Pearson product moment correlation coefficient = +0.99777; perfect correlation would be = 1.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, pp. 9–10.

- ^ In Gascoyne's day there was no way of determining latitude at sea reliably, so misplaced confidence was dangerous to mariners: Ravenhill 1976, p. 89.

- ^ By modern standards, the tip of the peninsula was indicated 1.5' too far south.

- ^ Ravenhill 1976, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. 9.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. vi.

- ^ The need to fit the map into pre-existing sheets may explain why a scale of slightly less than one-inch to the mile was chosen: Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. 12.

- ^ With a leather dabber, to ensure the ink was forced into each and every engraving line. The process had to be repeated after every impression.

- ^ Woodward 1978, p. 164-5.

- ^ a b Ravenhill & Padel 1991, p. ix.

- ^ Woodward 1978, p. 166.

- ^ Kresen Kernow.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, p. 64.

- ^ Holden, Herring & Padel 2010.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972a, pp. 335–339.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972a, pp. 339–341.

- ^ See also Ravenhill 1976, p. 89,

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Holden, Herring & Padel 2010, pp. 16–19.

- ^ Holden, Herring & Padel 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Holden, Herring & Padel 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, Editor's note (Ann Saunders).

- ^ Watson 1995, p. 235.

- ^ St Mary Whitechapel, St Leonard's Bromley, St John's Wapping (just a little riverside strip, much smaller than the main Wapping) and St Paul's Shadwell. Because those areas did not pay to be surveyed, they are left blank in Gascoyne's map: Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Strype 1720, IV.2.44.

- ^ English parish councillors originally met in a room in the local church, called the 'vestry', because the choir robed there.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 6–7, 1.

- ^ Quoted in Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 29.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 10.

- ^ For the individual maps and their scales see Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Carter 1985, p. 115.

- ^ All existing buildings mentioned in this article are listed and are described on the Historic England website.

- ^ Lysons 1811, pp. 685–688, 685*-688*, 689–691, 696–699.

- ^ Lysons 1811, pp. 685*-686* & nn..

- ^ Snow, Burney & Stringer 1899, p. 69. (The 'White Book'.) The 1956 edition continued so to assert.

- ^ Watson 1995, p. 236.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Watson 1995, p. 242.

- ^ The Spitalfields Trust 2016.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 28.

- ^ Watson 1995, pp. 237–8, 241.

- ^ Watson 1995, p. 237.

- ^ Smith 1784, pp. 186, 201.

- ^ Ashby 1896, pp. 22–24.

- ^ "Old". Later, there was a Novo.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 18, 21.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 17, 19, 27.

- ^ In Gascoyne's map: "Limehouse Street"; in later usage: "Fore Street".

- ^ In the C19 the dock was filled in and the site is now Paper Mill Wharf, 70 Narrow Street.

- ^ The green building is at the back of today's 70 Narrow Street.

- ^ Killock & Meddens 2005, p. 1. The title of the cited source refers to present-day Limehouse, which has absorbed Ratcliff.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 19, 26.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 25–6.

- ^ The main Stepney map; Limehouse; Mile End; Old Town and Bethnal Green.

- ^ Gascoyne & Harris 1995.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972b, pp. 63–4.

- ^ Ravenhill 1972a.

- ^ Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, pp. 10, 15.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography gives his death year as 1705. But that is to presuppose his widow applied for, and got, letters of administration in less than 2 months.

Sources

[edit]- Ashby, C. R. (1896). "The evidence of Christopher Wren". Survey of London Monograph 1, Trinity Hospital, Mile End (British History Online). London: Guild & School of Handicraft. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- Black, Jeanette D. (1978). "Mapping the English Colonies in North America: the Beginnings". In Thrower, Norman J. W. (ed.). The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Bowie, William (1929). "Notable Progress in Surveying Instruments". The Scientific Monthly. 29 (5). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 402–406. JSTOR 14687.

- Campbell, Tony (1973). "The Drapers' Company and Its School of Seventeenth Century Chart-Makers". In Wallis, Helen; Tyacke, Sarah (eds.). My Head Is a Map: a Festschrift for R.V. Tooley. London: Francis Edwards and Carta Press.

- Carter, Harold (1985). "Updating Human Geography: The Analysis of Town Growth 1. Problems, Sources and Methods". Teaching Geography. 10 (3). Geographical Association: 113–119. JSTOR 23751605.

- Duff, Meaghan N. (1998). Designing Carolina: The construction of an early American social and geographical landscape, 1670-1719 (PhD). William and Mary University. doi:10.21220/s2-gv7s-tx49. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- García Camarero, Ernesto (1959). "La Escuela cartográfica inglesa "At the Signe of the Platt"" (PDF). Boletín de la Real Sociedad Geográfica (in Spanish). XCV (1–6). Madrid: 65–68. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Gascoyne, Joel (1682). "A new map of the country of Carolina" (Map). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C.

- Gascoyne, Joel; Ravenhill, William; Padel, Oliver James (1991). "A Map of the County of Cornwall". Devon and Cornwall Record Society. Vol. 34 N.S. ISBN 0901853348.

- Gascoyne, Joel; Harris, John (1995) [First published 1703]. Saunders, Ann (ed.). An Actuall Survey of the Parish of St Dunstan Stepney alias Stebunheath Being one of the Ten Parishes in the County of Middlesex adjacent to the City of LONDON Describing exactly the Bounds of the NINE Hamlets in ye sd. Parish (facsimile) (Map). London: London Topographical Society, in association with Guildhall Library.

- "Grenville family of Stowe, Kilkhampton, Estate atlas". Kresen Kernow. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Holden, Paul; Herring, Peter; Padel, Oliver J. (2010). The Lanhydrock Atlas. A Complete Reproduction of the 17th-Century Cornish Estate Maps. The National Trsut:Cornwall Editions Fowey. ISBN 978-1-904880-32-5.

- Kelly, James William (2004). "Hack William (fl. 1670-1702)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- Killock, Douglas; Meddens, Frank (2005). "Pottery as plunder: a 17th century maritime site in Limehouse, London". Post-Medieval Archaeology. 39 (1): 1–91.

- Laddie; Prescott; Vitoria (2018). The Modern Law of Copyright. Vol. I (5 ed.). LexisNexis Butterworths. ISBN 9781474306898.

- London Gazette (13 December 1688). "Whitehall, Decemb 12". No. 2409. p. 2. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Lysons, Daniel (1811). The Environs of London Being an Historical Account of the Towns, Villages and Hamlets Within Twelve Miles of that Capital. Vol. II(2) (2 ed.). Cadell and Davies. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Macey, Samuel L. (1979). "Review: The Compleat Plattmaker: British Chart and Map Making, 1650-1750". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 12 (4). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 527–537. JSTOR 2738459.

- Maeer, Alaistair (2012). "The Baltic and the birth of a modern English maritime community: the Muscovy Company and nautical cartography, 1553-1665" (PDF). Revista Română de Studii Baltice și Nordice / The Romanian Journal for Baltic and Nordic Studies. 4 (2). Târgovişte: 19–49. ISSN 2067-1725. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Maeer, Alaistair S. (2020). "The cartography of the sea. Mapping England's 'mastery of the oceans'". In Jowitt, Claire; Lambert, Craig; Mentz, Steve (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Marine and Maritime Worlds 1400-1800. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781003048503. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Mayes, Charles R. (1957). "The Sale of Peerages in Early Stuart England". The Journal of Modern History. 29 (1). University of Chicago Press: 21–37. JSTOR 1872583.

- Merdinger, Charles E. (1954). "Surveying through the Ages: Part II. Development of Instruments". The Military Engineer. 46 (311). Society of American Military Engineers: 206–211. JSTOR 44570122.

- Pounds, N. J. G. (1945). "Lanhydrock Atlas". Antiquity. 19 (73). Cambridge University Press: 20–26. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00018780.

- Ravenhill, William (1971). "Joel Gascoyne's Stepney : his last years in pastures old yet new". Guildhall Studies in London History. II (4). Guildhall Library: 200–215.

- Ravenhill, William (1972a). "Joel Gascoyne: A Cartographer with Style". Geographical Magazine. XLIV (5): 335–41.

- Ravenhill, William (1972b). "Joel Gascoyne, a Pioneer of Large-Scale County Mapping". Imago Mundi. 26. Imago Mundi, Ltd: 60–70. JSTOR 1150645.

- Ravenhill, William (1974). "An Early Eighteenth-Century Cartographic Record of an Oxfordshire Manor" (PDF). Oxoniensia. 39. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society: 85–92. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Ravenhill, William (1976). "As to Its Position in Respect to the Heavens". Imago Mundi. 28. Imago Mundi, Ltd: 79–93. JSTOR 1150622.

- Ravenhill, W. L. D.; Johnson, David J. (1995). Saunders, Ann (ed.). Joel Gascoyne's engraved maps of Stepney, 1702-04. London: London Topographical Society, in association with Guildhall Library. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Ravenhill, W. L. D.; Padel, O. J. (1991). A Map of the County of Cornwall Newly Surveyed by Joel Gascoyne: Reprinted in Facsimile. Devon and Cornwall Record Society. ISBN 0-901853-34-8.

- Roncière, Monique de la (1965). "Manuscript Charts by John Thornton, Hydrographer of the East India Company (1669- 1701)". Imago Mundi. 19: 46–50. doi:10.1080/03085696508592265. JSTOR 1150328.

- Smith, Adam (1784). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Vol. I (3rd ed.). London: Strahan; Cadell. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Smith, Thomas R. (1978). "Manuscripts and Printed Sea Charts in Seventeenth-Century London: The Case of the Thames School". In Thrower, Norman J. W. (ed.). The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Snow; Burney; Stringer (1899). The Annual Practice. Vol. I. Sweet and Maxwell. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Strype, John (1720). A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (online ed.). ISBN 0-9542608-9-9. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Taylor, E. G. R. (1947). "The Surveyor". The Economic History Review. 17 (2). Wiley: 121–133. JSTOR 2590554.

- The Spitalfields Trust (2016). "37 Stepney Green, Stepney, London". Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Turnbull, David (1996). "Cartography and Science in Early Modern Europe: Mapping the Construction of Knowledge Spaces". Imago Mundi. 48: 5–24. JSTOR 1151257.

- Tyacke, Sarah (1973). "Map Sellers and the London Map Trade c.1650-1710". In Wallis, Helen; Tyacke, Sarah (eds.). My Head Is a Map: a Festschrift for R.V. Tooley. London: Francis Edwards and Carta Press.

- Tyacke, Sarah (1987). "58 • Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500—1660". In Harley, J. B.; Woodward, David (eds.). The History of cartography (PDF). Vol. 3. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1722–1753. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Verner, Coolie (1978). "John Seller and the Chart Trade in Seventeenth-Century England". In Thrower, Norman J. W. (ed.). The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Waters, David (1970). "The Iberian Bases of the English Art of Navigation in the Sixteenth Century" (PDF). Revista da Universidade de Coimbra. XXIV: 1–19 (separata). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Watson, Isobel (1995). "FROM WEST HEATH TO STEPNEY GREEN: BUILDING DEVELOPMENT IN MILE END OLD TOWN, 1660-1820". In Saunders, Ann Loreille (ed.). London Topographical Record. Vol. XXVII. ISBN 0 902087 35 5. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Woodward, David A. (1978). "English Cartography: A Summary". In Thrower, Norman J. W. (ed.). The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

External links

[edit]- A new map of the Country of Carolina hosted at the Library of Congress

- Gascoyne's An Actual Survey of the Parish of St Dunstan Stepney alias Stebunheath (the reduced 1755 version) hosted at the East London History Society: 1. Central section

- Ditto: 2. Bow, Bromley and Poplar

- Ditto: 3. Bethnal Green

- David J. Johnson's essay on the topography of Gascoyne's Stepney maps

KSF

KSF