Jon Burge

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 37 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 37 min

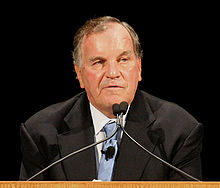

Jon Burge | |

|---|---|

Burge in 2010 | |

| Born | Jon Graham Burge December 20, 1947 |

| Died | September 19, 2018 (aged 70) Apollo Beach, Florida, U.S. |

| Education | University of Missouri |

| Occupation | Police commander |

| Employer | Chicago Police Department |

| Known for | Police brutality |

| Title | Detective Commander |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | United States Army/United States Army Reserve |

| Years of service | 1966–1972 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | Ninth Military Police Company of the Ninth Infantry Division |

| Battles / wars | Vietnam War |

| Awards | Bronze Star Purple Heart Army Commendation Medal (two) Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry |

Jon Graham Burge (December 20, 1947 – September 19, 2018) was an American police detective and commander in the Chicago Police Department. He was found guilty of lying about "directly participating in or implicitly approving the torture" of at least 118 people in police custody in order to force false confessions.[1]

Burge was a United States Army veteran who served in Asia during the Vietnam War. When he returned to the South Side of Chicago, he began a career as a city police officer, ending it as a commander. Following the shooting of several Chicago law enforcement officers in 1982, the police obtained confessions that contributed to convictions of two people. One filed a civil suit in 1989 against Burge, other officers, and the city, for police torture and cover-up; Burge was acquitted in 1989 because of a hung jury. He was suspended from the Chicago Police Department in 1991 and fired in 1993.

In 2002, a four-year review revealed numerous indictable crimes and other improprieties, but no indictments were made against Burge or his officers, as the statute of limitations for the crimes had expired. In 2003, Governor George Ryan pardoned four of Burge's victims who were on death row and whose convictions were based on coerced confessions.[2][3]

In 2008, Patrick Fitzgerald, United States Attorney for Northern Illinois, charged Burge with obstruction of justice and perjury in relation to testimony in a 2003 civil suit against him for damages for alleged torture. Burge was convicted on all counts on June 28, 2010, and sentenced to four and a half years in federal prison on January 21, 2011. He was released on October 3, 2014.

Early life

[edit]Raised in the community area of South Deering on the Southeast Side of Chicago,[4] Burge was the younger son of Floyd and Ethel Ruth (née Corriher) Burge. Of Norwegian descent, Floyd was a blue collar worker for a phone company while Ethel was a consultant and fashion writer for the Chicago Daily News.[5] Burge attended Luella Elementary School and Bowen High School where he showed interest in the school's Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps (JROTC). There he was exposed to military drill, weapons, leadership and military history.[4]

He attended the University of Missouri but dropped out after one semester,[5] which ended his draft deferment.[4] He returned to Chicago to work as a stock clerk in the Jewel supermarket chain in 1966.[5]

Military Career

[edit]In June 1966, Burge enlisted in the army reserve and began six years of service, including two years of active duty. He spent eight weeks at a military police (MP) school in Georgia.[4] He received some training at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he learned interrogation techniques. He volunteered for a tour of duty in the Vietnam War,[5] but instead was assigned as an MP trainer. He served as an MP in South Korea, gathering five letters of appreciation from superiors. On June 18, 1968, Burge volunteered for duty in Vietnam a second time,[5] and was assigned to the Ninth Military Police Company of the Ninth Infantry Division. He reported to division headquarters, where he was assigned to provide security as a sergeant at his division base camp, Đồng Tâm. Burge described his military police service as time spent escorting convoys, providing security for forward support bases, supervising security for the divisional central base camp in Đồng Tâm, and serving a tour as a provost marshal investigator.[4]

During his military service, Burge earned a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry and two Army Commendation Medals for valor, for pulling wounded men to safety while under fire.[5][6] Burge claimed to have no knowledge of or involvement in prisoner interrogation, brutality or torture in Vietnam. Burge was honorably discharged from the Army on August 25, 1969, aged 21.[4]

Police career

[edit]Jon G. Burge | |

|---|---|

| Police career | |

| Country | United States |

| Department | Chicago Police Department |

| Service years | 1970–1992 (fired February 10, 1993) |

| Rank | Sworn in as an officer – 1970 Detective – 1972 Sergeant – 1977 Lieutenant – 1981 Commander (Violent crimes) – 1981 Commander (Bomb & arson) – 1986 Detective Commander – 1988[7] |

Burge became a police officer in March 1970 at age 22 on the South Side of Chicago. In 20 years of service, he earned 13 commendations and a letter of praise from the Department of Justice.[6] In May 1972, he was promoted to detective and assigned to Area 2 (Pullman Area) Robbery.[4]

From 1981 to 1986, he served as the commander of the Area 2 Violent crimes Unit until he was promoted to commander of the Bomb and Arson Unit in 1986.[8]

In 1988, Burge became Area 3 (Brighton Park) detective commander.[9][10][11]

Torture

[edit]According to The Guardian, between 1972 and 1991, Burge "either directly participated in or implicitly approved the torture" of at least 118 people in police custody.[1] Federal prosecutors stated that Burge's use of torture began in 1972.[12][13] Burge was the leader of a group of police officers known variously as the "Midnight Crew", "Burge's Ass-Kickers", or the "A-Team", who abused suspects to coerce confessions.[1] Federal prosecutors stated that the "Midnight Crew" used methods of torture including beating, suffocation, burning, and electrical shock to the genitals, among other methods.[12]

Response to 1982 police shootings

[edit]The most prominent events related to his abuses occurred in winter 1982. In February 1982, there were several shootings of law enforcement officers on Chicago's South Side: two Cook County Sheriff's Officers were wounded and a rookie Chicago police officer was shot and killed on a CTA bus on February 5.[14][15]

On February 9, 1982, a person on the street grabbed a police officer's weapon, and shot and killed both the officer and his partner.[16][17][18] This last incident occurred within Burge's jurisdiction; he was a lieutenant and commanding officer of Area 2.[citation needed]

Burge was eager to catch those responsible and launched a wide effort to pick up suspects and arrest them. Initial interrogation procedures allegedly included shooting pets of suspects, handcuffing subjects to stationary objects for entire days, and holding guns to the heads of minors. Jesse Jackson, Operation PUSH spokesman; the Chicago Defender; and black Chicago Police officers were outraged. Renault Robinson, president of Chicago's Afro-American Police League characterized the dragnet operation as "sloppy police work, a matter of racism."[19] Jackson complained that the black community was being held under martial law.[20] The police captured suspects for the killings on February 9 through identification by other suspects. Tyrone Sims identified Donald "Kojak" White as the shooter, and Kojak was linked to Andrew and Jackie Wilson by having committed a burglary with them earlier on the day of the killings.[21]

Torture of Andrew Wilson

[edit]Andrew Wilson was arrested on the morning of February 14, 1982, for the murder of the last two police officers.[11] By the end of the day, he was taken by police and admitted to Mercy Hospital and Medical Center with lacerations on various parts of his head, including his face, chest bruises and second-degree thigh burns.[11] More than a dozen of the injuries were documented as caused while Wilson was in police custody.[6]

Both Andrew Wilson and his brother Jackie confessed to involvement in the February 9 fatal shootings of the police officers.[22] A medical officer who saw Andrew Wilson sent a memo to Richard M. Daley, then Cook County State's Attorney, asking for his case to be investigated on suspicion of police brutality.[23]

Criminal trials

[edit]During a two-week trial in 1983, Andrew Wilson was convicted of the killings and given a death penalty sentence. His brother, Jackie, was convicted as an accomplice and given a life sentence.[24] Both appealed their convictions. In 1985, Jackie Wilson's conviction was overturned by the Illinois Appellate Court because his right to remain silent had not been properly explained by the police.[24]

As Andrew Wilson had been given a death sentence, his case was not reviewable on the same grounds by the Appellate Court, and it went directly to the Illinois Supreme Court.[24] In April 1987, the Supreme Court overturned Andrew's conviction with a ruling that his confession had been coerced involuntarily from him while under duress. It ordered a new trial.[25]

In October 1987, the appellate court further ruled that Jackie Wilson should have been tried separately from his brother. He was convicted as an accomplice at his second trial. The court also ruled that evidence against Andrew Wilson, regarding other matters for which the police wanted him, was incorrectly admitted at his trial on murder charges.[26]

His case was remanded to the lower court for retrial. Andrew Wilson was convicted at his second trial in June 1988.[27] After five days of deliberation, the jury was unable to agree on Wilson's eligibility for the death penalty; ten women were in favor of imposing this sentence and two men opposed it.[28] The following month Andrew Wilson was sentenced to life imprisonment.[29]

Wilson's civil suit against officers and city

[edit]In 1989, seven years after his arrest in 1982, Andrew Wilson filed a civil suit against four detectives (including Burge), a former police superintendent, and the City of Chicago. He said that he had been beaten, suffocated with a plastic bag, burned (by cigarette and radiator), and treated with electric shock by police officers when interrogated about the February 1982 murders; he also had been the victim of the pattern of a police and city cover-up.[30]

Jury selection for the civil trial began on February 15, 1989.[11] The original six-person jury (as was customary for civil trials in Illinois) consisted of two women and four men. By ethnicity it was made up of three African Americans, one Latino, and two whites.[31]

When Burge took the stand on March 13, 1989, he denied that he injured Andrew Wilson during questioning and denied any knowledge of any such activity by other officers.[32][33]

Wilson's legal team, led by G. Flint Taylor of the People's Law Office, received anonymous letters during the trial from a person claiming to be an officer who worked with Burge. This person alleged that the Wilson case was part of a larger pattern of police torture of African-American suspects, which was sanctioned by Burge.[34] U.S. District Judge Brian Barnett Duff did not permit the jury to hear this anonymous evidence.[35]

Gradually, the cases of the other officers named in Wilson's suit were resolved. On March 15, 1989, Sergeant Thomas McKenna was acquitted of brutality,[36] and on March 30, 1989, detectives John Yucaitis and Patrick O'Hara were each acquitted of charges by a unanimous jury;[37] however, the jury was at an impasse regarding Burge.[37]

Duff ordered a retrial for Burge, former Police Supt. Richard J. Brzeczek, and the City of Chicago on two other outstanding charges (conspiracy and whether the City of Chicago's policy toward police brutality contributed to Wilson's injuries).[31][38] Burge was acquitted of these charges in a second trial, which began on June 9, 1989, and lasted nine weeks.[39][40]

In the verdict of the civil case, jurors found that Chicago police officers employed a policy of using excessive force on black suspects.[41]

Increasing reports of torture and new civil suits

[edit]The first lengthy report of torture by the Chicago police was published beginning in January 1990 in the alternative weekly Chicago Reader.[19] Through that year, as additional material was published by the Chicago Tribune, civil activists and victims of Burge pushed for disciplinary action against the officer.[42][43]

Danny K. Davis, who was running for Chicago mayor in the Democratic primary scheduled for February 26, 1991, made police brutality and excessive force an issue in the campaign. He sought an independent citizens' review of the police department.[13] On January 28, 1991, Amnesty International called for an investigation into police torture in Chicago.[44][45] When the city's mayor, Richard M. Daley, seemed reluctant to initiate an investigation, his opponent Davis questioned whether there was a police and city coverup.[41]

Eventually, after pressure by citizens' organizations and anti-brutality organizations, the police department resumed an internal investigation.[46]

In 1991, Gregory Banks filed a civil suit for $16 million in damages against Burge, three colleagues, and the City of Chicago for condoning brutality and torture. He said that he had falsely confessed in 1983 to murder after he was tortured by officers: they placed a plastic bag over his head, put a gun in his mouth, and performed other acts. He claimed officers abused eleven other suspects, using such measures as electro-shock. The suit was brought by the People's Law Office attorneys who had represented Andrew Wilson in the 1989 police brutality case.[47] The suit described 23 incidents against black and Hispanic suspects between 1972 and 1985.[48] Banks' suit named Sergeant Peter Dignan as one of the officers involved in the abuses. In 1995, Dignan was promoted for meritorious service, even though the City of Chicago had settled out of court with Banks on his suit.[49]

In 1993, Marcus Wiggins filed a third suit against Burge and the city, saying that he had been subjected at the age of 13 to electric shock during interrogation and forced into a coerced confession.[50][51]

In November 1991, the Chicago Police Department's Office of Professional Standards (OPS), the internal affairs division that investigates complaints of police misconduct,[52] acknowledged an October 25, 1991, request for action against Burge. This was a common precursor to a police dismissal and gave the City of Chicago's Corporation counsel 30 days to consider the report.[53][54] Burge was suspended for 30 days pending separation, starting on November 8, 1991.[55]

The Chicago Police Board set a November 25 hearing to formalize the firing of Burge and two detectives based on 30 counts of abuse and brutality against Wilson.[56] The hearing reviewed the internal police investigation finding that Burge and Detective John Yucaitis had physically abused Andrew Wilson in 1982, while Detective Patrick O'Hara did nothing to stop them.[57]

The suspension attracted controversy after the 30-day period ended, and the officers remained suspended without pay. They sued for reinstatement,[58] but their claims for reinstatement were initially denied.[59]

During the hearing, an internal report, which had been suppressed for years, revealed earlier police review findings that criminal suspects were subjected to systematic brutality at the Area 2 detective headquarters for 12 years and that supervisory commanders had knowledge of the abuses.[60][61]

During the February 1992 hearings, several alleged victims testified against Burge.[62][63][64]

The internal hearing concluded in March 1992,[65] and the Chicago Police Board found Burge guilty of "physically abusing" an accused murderer 11 years earlier; it ordered his firing from the police force on February 10, 1993.[66]

Detectives Yucaitis and O'Hara were given 15-month suspensions without pay and reinstated, which amounted to a penalty equal to time served.[6][66][67] Upon reinstatement the two detectives were initially demoted,[68] but about one year later, they were reinstated at full-rank with backpay for time served while demoted.[69]

Burge attempted to have the ruling overturned,[70][71] but the suspension and subsequent firing were upheld.[72][73]

Due to the internal hearing, the City of Chicago was simultaneously paying lawyers to defend Burge during an appeal by Wilson and a new civil case by Banks, while employing lawyers to prosecute him on departmental charges.[74] The City hired outside counsel to prosecute the detectives at the internal hearing.[57] After having spent $750,000 to defend Burge in the Wilson case, the City of Chicago debated whether to follow normal procedures and pay for the defense of its police officers.[75]

In 1993, Andrew Wilson was granted a new judicial hearing in his civil case against Burge by the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.[76] The ruling was based on the fact that during the 1989 civil suit, the officers' defense had worked to "immerse the jury in the sordid details of Wilson's crimes" and did not respond to a suspect's "right to be free from torture and the correlative right to present his claim of torture to a jury that has not been whipped into a frenzy of hatred".[77]

An investigation conducted by Chicago Police Department's Office of Professional Standards (OPS) concluded in 1994 that Burge and his detectives engaged in "methodical" and "systematic" torture, and "The type of abuse described was not limited to the usual beating, but went into such esoteric areas as psychological techniques and planned torture."[78]

Abuse-related legal decisions

[edit]As more information about Burge's tenure was published, activists worked on behalf of Chicago inmates on death row who claimed to have been wrongfully convicted. In 1998, representatives from the MacArthur Justice Center at the University of Chicago Law School, the London-based International Center for Criminal Law and Human Rights, law professor Anthony Amsterdam, former federal judges George N. Leighton and Abner Mikva, Illinois judge R. Eugene Pincham, and activist Bianca Jagger, called for a stay of execution for Aaron Patterson, a death row inmate from Chicago. His conviction for murder was based primarily on a confession which he claimed was coerced by torture from Burge and his officers.[79][80][81]

In 1999, lawyers for several death row inmates began to call for a special review of convictions that were based on evidence and confessions extracted by Burge and his colleagues. These inmates: Aaron Patterson; Madison Hobley; Stanley Howard; Leonard Kidd; Derrick King; Ronald Kitchen; Reginald Mahaffey; Jerry Mahaffey; Andrew Maxwell, and Leroy Orange, became known as the "Death Row 10".[82]

In the 1990 Goldston Report, the City of Chicago listed 50 alleged instances of police brutality and abuse by Burge and other officers.[83] Chicago had struggled for decades with the issue of coerced confessions; in the 1990s it quietly reopened several controversial brutality cases. Despite an extensive investigation into the actions by a number of police employees, few others but Burge were sanctioned.[84]

Several politicians, including US Representative Bobby Rush, requested that State's Attorney Richard A. Devine seek new trials for the Death Row 10 who were allegedly tortured by Burge into making coerced confessions.[85] Devine met with representatives and supporters of the inmates[86] and was convinced to request that the Illinois Supreme Court stay proceedings against three of the inmates.[87] However, the Illinois Supreme Court denied Devine's request.[88][89] Rush sought out Attorney General Janet Reno to pursue federal intervention.[90]

In February 1999, David Protess, a Northwestern University journalism professor, and his students were studying cases of people on death row. They discovered evidence related to death row inmate Anthony Porter that might help exonerate him.[91][92]

The students produced four affidavits and a videotaped statement that attributed guilt for the crime to another suspect. They obtained recantations by some witnesses of their testimony at trial. One witness claimed that he named Porter as a suspect only after police officers threatened, harassed and intimidated him into doing so.[93][94]

In 2000,[95] Governor Ryan placed a moratorium on executions in Illinois after courts exonerated and freed 13 death row inmates who had been wrongfully convicted.[6][96] Ryan also promised to review the cases of all Illinois death row inmates.[97]

Given the number of cases of alleged brutality to be investigated, inmates who claimed to have been abused and gave coerced confessions were offered reduced sentences in exchange for dropping charges. A plea agreement was reached with one convicted victim.[98][99] Aaron Patterson rejected the plea deal.[100]

On January 11, 2003, having lost confidence in the state's death penalty system,[2] the outgoing Governor Ryan commuted the death sentences of 167 prisoners on Illinois' death row.[96][3] He granted clemency by converting their death sentences to sentences of life without parole in most cases, while reducing some sentences.[101][102]

In addition, Ryan had already pardoned four death row inmates: Madison Hobley, Aaron Patterson, Leroy Orange and Stanley Howard, who were among the ten who claimed they were coerced into confessing by Burge and his officers and had been wrongfully convicted.[103][104]

Daley, at the time the Cook County State's Attorney, has been accused by the Illinois General Assembly of failing to act on information he possessed on the conduct of Burge and others.[44] Daley acknowledged his responsibility to be proactive in stopping torture, but denies any knowledge which could have made him responsible.[105]

On July 19, 2006, Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr. issued a press release calling Mayor Daley culpable, possibly even criminally culpable, for his failure to prosecute until the statute of limitations had run out.[106] Jackson called for an investigation to determine if there was any planned delay in order to allow the cases to expire.[106] Death penalty opponents requested that U.S. President Bill Clinton follow Ryan's lead in halting executions.[95]

In August 2000, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed or remanded two Burge-related death row cases based on allegations of torture by police.[107][108]

Civil suits by pardoned men

[edit]After being pardoned by Governor Ryan, Burge's accusers from death row began to file lawsuits against the city and its officers. Madison Hobley was the first of the four pardoned inmates to file a federal lawsuit in May 2003, represented by civil rights attorney Jon Loevy.[109][110] Aaron Patterson followed in June with a lawsuit,[111][112] and Stanley Howard filed suit in November 2003.[113][114] LeRoy Orange also filed suit.

The four men filed suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois against the City of Chicago, Burge, several of Burge's former subordinate police detectives, Cook County, and a few current and former State's Attorneys and assistant state's attorneys of Cook County (the precise list of police officers and prosecutors varied somewhat from plaintiff to plaintiff). Although each case was randomly assigned to a different district judge, the parties all consented to have the four cases consolidated for discovery management before Magistrate Judge Geraldine Soat Brown. In December 2007, a settlement of $19.8 million was reached between the plaintiffs and the so-called "city defendants," consisting of the City of Chicago, Burge, the other former detectives, and Richard M. Daley (former Cook County State's Attorney and Mayor of Chicago at the time of the settlement).[115][116][117][118]

Special investigations

[edit]

The Chicago Police Department had conducted an investigation of Burge through its Office of Professional Standards (OPS). Known as the Goldston Report (September 28, 1990) for its lead investigator,[119] this internal report determined that "the preponderance of evidence is that abuse did occur and that it was systematic."[120]

The report, never publicly released, "listed the names of fifty alleged victims of torture and brutality, the names of detectives who had been involved, and stated: 'Particular command members were aware of the systematic abuse and perpetuated it either by actively participating in same or failing to take any action to bring it to an end'."[119]

In 2002, the Cook County Bar association, the Justice Coalition of Chicago and others petitioned for a review of the allegations against Burge.[121] Edward Egan, a former prosecutor, Illinois Appellate Court jurist was appointed as a Special State's Attorney ("special prosecutor") to investigate allegations dating back to 1973.[122] He hired an assistant, several lawyers, and retired Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents.[6] Former prosecutor Robert D. Boyle was also appointed as a special prosecutor.[123]

In 2003, former Chief of the Special Prosecution Division of the U.S. Attorney's Office, Gordon B. Nash Jr., was appointed as an additional special prosecutor.[124]

A total of 60 cases were ordered to be reviewed.[120] A special prosecutor was hired because Cook County State's Attorney, Richard Devine, had a conflict of interest stemming from his tenure at the law firm of Phelan, Pope & John, which had defended Burge in two federal suits.[120] Criminal Courts Judge Paul P. Biebel Jr. presided over the determination of the need of a review to determine the propriety of criminal charges and the appointment of the special prosecutor.[120]

During the written phase of the investigation, Burge and eight other officers pleaded the Fifth Amendment.[125] On September 1, 2004, Burge was served with a subpoena to testify before a grand jury in an ongoing criminal investigation of police torture while in town for depositions on civil lawsuits at his attorney's office.[126] Burge pleaded the Fifth Amendment to virtually every question during a 4-hour civil case deposition.[126] He answered only questions about his name, his boat's name (Vigilante), and his $30,000 annual pension.[126] The City of Chicago continues to be bound by court order to pay Burge's legal fees.[126] Eventually, three police officers were granted immunity in order to further the investigation into Burge.[127]

The incident prompted the city to request the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to allot the torture victims an hour-long hearing at their October 2005 session.[128][129]

On May 19, 2006, the court ruled that the city had to release the special report on torture accusations, as there was a compelling public interest in the material.[130] Previous police investigations had not been publicly released. On June 20, 2006, the Illinois Supreme Court unblocked the release of the special report by Egan, which took 4 years and cost $17 million.[131] In the end the group evaluated 148 cases.[96] The investigation revealed that in three of the cases, prosecutors could have proved, beyond a reasonable doubt in court, that torture by the police had occurred; five former officers including Burge were involved.[96][132] Half of the claims were deemed credible, but because the timing of the cases exceeded the statute of limitations for police abuse of suspects, no indictments were made.[132]

Daley and all law enforcement officials who had been deposed were excluded from the report.[132] Among the final costs were $6.2 million for the investigation and $7 million to hire outside counsel for Burge and his cohort.[133] Egan explained his report to the public with legal theories and federal jurisdiction issues.[134]

On the same day that the court ruled to release the special report, the 36th session of the United Nations Committee Against Torture issued its "Conclusions and recommendations of the Committee against Torture" report of the United States. The document states:

The Committee is concerned at allegations of impunity of some of the State party's law-enforcement personnel in respect of acts of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. The Committee notes the limited investigation and lack of prosecution in respect of the allegations of torture perpetrated in areas 2 and 3 of the Chicago Police Department (art. 12). The State party should promptly, thoroughly and impartially investigate all allegations of acts of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment by law-enforcement personnel and bring perpetrators to justice, in order to fulfil its obligations under article 12 of the Convention. The State party should also provide the Committee with information on the ongoing investigations and prosecution relating to the above-mentioned case.[135]

Burge in Florida

[edit]After being fired, Burge moved to Apollo Beach, Florida, a suburb of Tampa. He continued to receive a police pension as entitled under Illinois state law.[6] In 1994, he bought a wood-frame home for $154,000 and a 22 ft (6.7 m) motorboat.[6] While a police officer, Burge had owned a 40-foot (12 m) cabin cruiser named The Vigilante, which he maintained at Burnham Harbor.[136] Upon retiring at full pension, he ran a fishing business in Florida.[82] The precise amount of his pension is not a matter of public record, but he was eligible for 50% of his approximately $60,000 salary.[137]

Aftermath: legal changes

[edit]In response to the revelations of torture by Chicago police, the state legislature began to consider a bill in 1999 mandating the videotaping of interrogations in homicide cases.[138][139] Then-Illinois State Senator Barack Obama pushed the mandated video recording bill through the Illinois State Senate in 2003.[140] It was put into effect in 2005, after interrogation rooms had been outfitted and training of officers had been done.[141]

There were numerous legislative reforms passed in 2003 that were related to improving use of the death penalty and preventing wrongful convictions. After Governor Rod Blagojevich, a Democrat, vetoed some provisions,[142][143] the state house voted unanimously 115–0 to pass the package, overriding his veto. Reforms included giving the "Illinois Supreme Court greater power to throw out unjust verdicts, gives defendants more access to evidence, and bars the death penalty in cases based on a single witness. The reforms are among the 80 recommendations made by the Illinois Commission on Capital Punishment, formed in 2000 by former Governor George Ryan to address wrongful convictions and the state's broken death penalty system."[144]

Arrest

[edit]Although Burge had been presumed to be protected by a statute of limitations, the US Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, Patrick Fitzgerald, in October 2008 charged Burge with two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury.[145][146] Burge was arrested on October 21, 2008, at his home in Apollo Beach by FBI agents.[147]

Under the charges, Burge could have been subject to 40 years in prison for the two obstruction counts and five years on the perjury count.[148] The charges were the result of convicted felon Madison Hobley's 2003 civil rights lawsuit alleging police beatings, electric shocks and death threats by Burge and other officers against dozens of criminal suspects.[147]

Burge pleaded not guilty and was released on $250,000 bond.[149] Fitzgerald noted that although Burge was being charged with lying, and not the torture to which the statute of limitations applied, he believed Burge to be guilty of both.[149]

In the October 21 press conference, Fitzgerald stated that Burge had "lied and impeded court proceedings" during his 2003 written testimony.[145] The indictment's perjury count referenced Burge's written testimony given in Madison Hobley's federal civil lawsuit, where he denied committing torture: “I have never used any techniques set forth above as a means of improper coercion of suspects while in detention or during interrogation.”[150] In the indictment, the prosecution stated that Burge understood that he was a participant in and was aware of "such events involving the abuse or torture of people in custody".[145] The trial was set for May 11, 2009.[149] Instead, on April 29, Burge filed a change-of-venue motion, in relation to the lawsuit filed by former Death Row inmate Madison Hobley, and Burge's trial was set for October 29, 2009.[151][152]

Also in April, Cortez Brown, an inmate who had sought a new trial with respect to his conviction in two 1990 murders, to which he said he had confessed under physical coercion, had already subpoenaed two Chicago police detectives for his May 18, 2009, hearing. He won the right from a Cook County judge to subpoena Burge. Burge was expected to exercise his 5th Amendment right not to incriminate himself.[153] The Florida judge refused to grant the subpoena, given the likelihood that Burge would exercise his 5th Amendment right.[154]

On May 6, 2010, jury selection began for the Burge trial for perjury and obstruction of justice.[155] 80 potential jurors were given a 29-page questionnaire to complete. Attorneys had until May 24 to review the questionnaires before final jury selection began. An additional batch of 90 potential jurors was given a questionnaire on May 17.[156]

The trial heard its first testimony on May 26.[157] Burge testified in his own defense for six hours on June 17 and on subsequent days.[158][159] Closing arguments were heard on June 24,[160] and jury deliberations began on June 25.[161]

On June 28, Burge was convicted on all three counts: two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury.[162]

On January 21, 2011, Burge was sentenced to four and a half years in federal prison by U.S. District Judge Joan Lefkow.[163][164][165] The federal probation office had recommended a 15- to 21-month sentence, while prosecutors had requested as much as 30 years.[166] Burge served 90% of his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution Butner Low near Butner, North Carolina. Burge's projected release date was February 14, 2015;[167] he was released from prison on October 3, 2014, to serve the remainder of his sentence in a halfway house.[168] Plans to file federal civil lawsuits against Burge, Daley, and others were announced in 2010.[169]

City costs for police misconduct

[edit]In April 2014, the Better Government Association, a non-partisan watchdog group, reported that the city of Chicago had spent more than $521.3 million in the previous decade on lawsuit settlements, judgments, and legal fees for defenses related to police misconduct. In 2013, the most expensive year, it paid more than $83.6 million.[170]

The city paid a total of $391.5 million in settlements and judgments. More than a quarter, or $110.3 million, was related to 24 wrongful-conviction lawsuits, a dozen of which involved Burge, whose detectives were accused of torturing confessions out of mostly black male suspects over many years. Overall, the city has paid alleged victims of Burge led detectives more than $57 million.[170]

Torture Inquiry Relief Commission

[edit]In 2009, the state legislature passed a bill authorizing creation of the Illinois Torture Inquiry Relief Commission (TIRC) to investigate cases of people "in which police torture might have resulted in wrongful convictions". In some cases, allegedly coerced confessions were the only evidence leading to convictions. Its scope is limited to people tortured by Burge or by other officers under his authority, as made explicit in the law and by an appellate court review in March 2016. That month, the court also ruled that the TIRC does have jurisdiction in cases of detectives who once served under Burge, even if the claim was for a later incident.[171]

Beginning in 2011, the TIRC has referred 17 cases to the circuit court for judicial review for potential relief. Three people have been freed based on review of their cases. Individuals may initiate claims to the commission. As of April 2016, 130 other cases have been heard of torture that was not committed by Burge or his subordinates. The city and state are struggling to determine how to treat this high number of torture victims in a just way. The sponsors of the bill tried to amend it in 2014 to expand its scope to all claims of torture by police in Chicago, but were unable to get support in the state house. They will try again.[171]

Culture of violence

[edit]In 2011, the Cook County State's Attorney, Anita Alvarez, compelled the Office of Conviction Integrity to review cases of convictions dependent on evidence from homicide detective Richard Zuley of the Chicago Police Department.[172] In 2013, Lathierial Boyd, a man whose conviction was dependent on Zuley's evidence, won exoneration and freedom after 23 years in prison due to wrongful conviction; it was found that Zuley had suppressed exculpatory evidence.[173]

Discussing the larger culture of violence that Chicago police had created, journalist Spencer Ackerman in February 2015 reported that Zuley, by then retired from CPD, had served in 2003–2004 with the US Navy Reserve as an interrogator at Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, established by the George W. Bush administration.[174] (Zuley had returned to the CPD after his Navy service.)[175][174]

In 2003, one of his subjects was the high-profile detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi, for whom the Secretary of Defense had authorized extended interrogation techniques, since classified as torture. Slahi's memoir, Guantanamo Diary, was published in January 2015, and quickly became an international bestseller.[174] He detailed the torture he suffered. Ackerman noted that inmates with claims or suits against Zuley had recounted details that are similar to the physical and psychological abuse against Slahi.[174] Local Chicago publications identified Zuley as a protege of Burge,[175][174] but Ackerman said that the two officers never served together. Zuley primarily served on the North Side.[176]

City reparations

[edit]On April 14, 2015, the Mayor of Chicago, Rahm Emanuel, announced the creation of a $5.5 million city fund for individuals who could prove that they were victimized by Burge.[177]

Burge broke his silence to say he found it hard to believe that Chicago political leadership could "even contemplate giving reparations to human vermin".[178] The fund was approved by the Chicago City Council on May 6, 2015.[179]

In approving the reparations, Chicago became the first municipal government to approve compensating victims who have valid claims of police torture.[180] Under the terms, about 60 living victims would each be eligible to receive up to $100,000. The living survivors and their immediate families, and the immediate families of the deceased torture victims, would also be given access to services, including psychological counseling and free tuition to the City Colleges of Chicago. Additionally, the city approved building a public memorial to the deceased victims[181] and established a requirement that students in the eighth and tenth grades attending Chicago Public Schools learn about the Burge legacy.[180]

At the May Council meeting, as more than a dozen Burge survivors looked on, Mayor Emanuel offered an official apology on behalf of the City of Chicago, and the aldermen stood and applauded.[182] G. Flint Taylor, an attorney with the People's Law Office and part of the legal team that negotiated the deal, said in an interview that the "non-financial reparations make it truly historic".[183] Taylor predicted that the reparations will be a "beacon for other cities here and across the world for dealing with racist police brutality."[180]

Death

[edit]Burge, who never married, died at age 70 on September 19, 2018, at his home in Apollo Beach, Florida.[184][185][186] He had been previously treated for prostate cancer.[187][185]

In response to his death, Reverend Jesse Jackson said: "As a person, may his soul rest in peace. As a policeman, he did a lot of harm to a lot of people ... We pray for his family, because that's the appropriate thing to do."[188]

Representation in other media

[edit]The Burge case has been chronicled in various formats in the mass media.

- The book Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People (2001, ISBN 0-520-23039-6) by John Conroy, a reporter for the Chicago Reader who covered the events, includes four chapters on Burge's story.[6][189]

- The 1994 Public Broadcasting Service documentary film, entitled The End of the Nightstick and co-produced with Peter Kuttner, analyzed the torture charges against Burge.[190]

- The television show Untouchable: Power Corrupts (2015 episode "Burge")[191]

- The television series The Good Fight refers to Burge in episode 3 of season 4.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Baker, Peter C (March 8, 2019). "In Chicago, reparations aren't just an idea. They're the law". The Guardian. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Wilgoren, Jodi (January 10, 2003). "Illinois Expected To Free 4 Inmates". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Flock, Jeff (January 13, 2003). "'Blanket commutation' empties Illinois death row". CNN. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Tools of Torture". Chicago Reader. February 4, 2005. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Conroy, pg. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i LaPeter, Leonora (August 29, 2004). "Torture allegations dog ex-police officer". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Burge Federal Indictment". United States Attorney. May 13, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ "Burge to head bomb and arson unit". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. August 14, 1986. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Casey, Jim; Phillip J. O'Connor (January 27, 1988). "51 cops get new jobs in shakeup of Martin staff". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Wattley, Philip (January 27, 1988). "City Police Chief Reshuffles Staff". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Grady, William (February 15, 1989). "Police Brutality Suit Heads To Trial". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Guarino, Mark (October 2, 2014). "Disgraced Chicago police commander accused of torture freed from prison". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Spielman, Fran (December 25, 1990). "Davis urges new review of police brutality cases". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "James E. Doyle". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ Conroy, p. 23.

- ^ Conroy, pp. 21–22.

- ^ "Patrolman Richard James O'Brien". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ "Patrolman William P. Fahey". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ a b John Conroy (January 26, 1990). "Police Torture in Chicago: House of Screams". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Conroy, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Conroy, p. 24.

- ^ "2 Officers Cleared of Torturing Suspect". Chicago Tribune. September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Deaf to the Screams". Chicago Reader. July 31, 2003.

- ^ a b c Mount, Charles (December 21, 1985). "Judge's Error Means New Trial in Killing of Cops". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Tybor, Joseph R. (April 3, 1987). "Verdict Overturned in Killing of 2 Cops". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Cose, Larry (October 1, 1987). "2nd brother wins new trial in cop killings". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Seigel, Jessica; Matt O'Connor (June 21, 1988). "Man Is Found Guilty 2D Time in Cop Killings". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Seigel, Jessica; Matt O'Connor (June 28, 1988). "Cop Killer Spared Death As 2 on Jury Hold Out". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ O'Connor, Matt (July 13, 1988). "Andrew Wilson Gets Life Sentence in Killing of Cops". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Conroy, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Drell, Adrienne (April 3, 1989). "Jurors think a retrial useless for cop killer". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Drell, Adrienne (March 14, 1989). "Cop denies beating, torture". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Marja (March 14, 1989). "Police Officer Denies Torturing of Suspect". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Sharon. "2 decades of abuse charges, finally a sentencing in police scandal that haunted city". Streetgangs.com. The Associated Press. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Conroy, John (January 25, 1990). "House of Screams". Reader. Sun-Times Media LLC. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ "Judge Clears Police Officer in Rights Suit". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. March 16, 1989. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Drell, Adrienne (March 31, 1989). "2 cops cleared of brutality – no verdict on 3rd". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Grady, William (April 11, 1989). "Cop Killer's Attorneys, Judge at Odds Over Start of New Trial". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "Cop Killer Gets Rights Trial Delayed". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. April 12, 1989. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Drell, Adrienne (August 9, 1989). "3 cops win in killer's brutality suit". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Long, Ray (January 31, 1991). "Davis charges cop cover-up". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Brutality Alleged on Southwest Side". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. May 13, 1990. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Chicagoland". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. August 1, 1990. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Amendment to House Bill 765". Illinois General Assembly. March 27, 2007. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ Long, Ray (January 29, 1991). "Group wants police commander fired". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (November 26, 1991). "Strategy hinted for hearing on police brutality charges". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Rossi, Rosalind (October 11, 1991). "$16 million suit alleges torture by city cops". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Lawsuit Charges Police Brutality". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. October 11, 1991. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (March 19, 1995). "Daley Won't Block Controversial Cop's Promotion". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Seibel, Tom (January 14, 1993). "Cop Accused in Torture Suit – Shock Treatment Used to Get Confession, Youth Says". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ McMahon, Colin; Christine Hawes (January 14, 1993). "Suit Alleges Cop Torture of Youth". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on September 8, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Sanders, Francine J. (September 18, 2013). "A former investigator of police misconduct on the questions she never asked". chicagoreader.com.

- ^ Hausner, Les (November 8, 1991). "Probers seek action against cop – Commander accused of excessive force". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Jackson, David (November 8, 1991). "Brutality Charges To Be Reviewed". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, David (November 10, 1991). "Questions About Police Torture Persist". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ O'Connor, Phillip J. (November 14, 1991). "Police Board sets November 25 dismissal hearing for 3". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "City Hires Attorney in Police Firings". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. November 19, 1991. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Rossi, Rosalind (December 21, 1991). "3 cops accused of brutality sue to challenge suspensions". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "3 Suspended Officers Lose Bid in Court To Win Reinstatement". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. December 27, 1991. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (February 8, 1992). "Report cites 12 years of S. Side cop brutality". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Blau, Robert; Jackson, David (February 9, 1992). "Police Study Turns Up Heat on Brutality". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Stein, Sharman (February 11, 1992). "Burge-Case Panel Hears of Torture". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 23, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Stein, Sharman (February 20, 1992). "Second Convict Tells of Torture By Burge". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Stein, Sharman (February 21, 1992). "3rd Witness Calls Burge A Torturer". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Burge Case Ruling Seen Far Away". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. March 20, 1992. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Nicodemus, Charles (February 11, 1993). "Burge Fired in Torture Case – Guilty of Abusing '82 Murder Suspect". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Stein, Sharman (February 11, 1993). "Police Board Fires Burge For Brutality". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (February 12, 1993). "Cops in Brutality Case Lose Detective Rank". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Demoted Detectives Win Reinstatement". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. January 28, 1994. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Ortiz, Lou (March 13, 1993). "Burge Sues to Overturn His Firing". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Burge Asks To Regain Police Job And Pay". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. March 13, 1993. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Fegelman, Andrew (February 11, 1994). "Cop Firing In Torture Case Upheld". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Lehmann, Daniel J. (February 11, 1994). "Court Backs Cop's Firing for Torture". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (November 17, 1991). "Special prosecutor urged in police torture hearing". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (November 29, 1991). "City mum on if it'll pay to defend cop in suit". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Lehmann, Daniel J. (October 5, 1993). "Cop-Killer Gets OK To Seek Damages". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Crawford, Jan (October 5, 1993). "Cop Killer's Torture Suit Revived". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Paige Bierma (July 1994). "Torture behind bars: right here in the United States of America". progressive.org. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007.

- ^ "Aaron Patterson", Center on Wrongful Convictions, Northwestern Pritzker School of Law

- ^ Mills, Steve (December 17, 1998). "Convicted Killer Wins Support in Battle To Overturn Death Sentence". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Drell, Adrienne (December 11, 1998). "Petitioners want inmate spared – Death penalty foes say cop tortured Patterson". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Nicodemus, Charles (February 3, 1999). "Lawyers urge review of 10 capital cases". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (February 3, 1999). "Death Row Convictions Tied To Cop Brutality". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (February 23, 1999). "Brutality Probe Haunts City". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (March 19, 1999). "Re-try 'Death Row 10' case, Devine urged". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (April 27, 1999). "Devine Hears Appeal For Death Row Inmate". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Lehmann, Daniel J. (July 28, 1999). "Death Row delays sought – Devine wants 3 cases reviewed". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "High court rejects Devine's bid to stay three executions". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. August 27, 1999. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (August 26, 1999). "Judge Orders 3 Death Penalty Cases To Move Ahead". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Loven, Jennifer (July 29, 1999). "Reno Meets on Chicago Police>Lawmaker, Activists List Their Complaints With Attorney General". Peoria Journal Star. Newsbank. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ McRoberts, Flynn (February 7, 1999). "NU Professor Now A Media Superstar". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ Zorn, Eric (February 2, 1999). "Evidence Grows That Wrong Man Is on Death Row". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Holt, Douglas (February 3, 1999). "Death Row Inmate's Hearing Is Put on Hold – NU Students Turn Over Evidence in Porter Case". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Forte, Lorraine (February 2, 1999). "Murder case witness recants, saying police coerced him". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ a b Fingeret, Lisa (February 14, 2000). "Death Penalty Foes Call For Federal Moratorium". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ferkenhoff, Eric (July 19, 2006). "Chicago's Toughest Cop Goes Down". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve; Ken Armstrong (March 5, 2002). "Hard calls face Ryan in Death Row review". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Mills, Steve (January 21, 2001). "Convicted Killer Drops Claim of Cop Torture To Win Freedom". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Mills, Steve (September 27, 2001). "Devine offers Death Row deal". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Mills, Steve; Armstrong, Ken (October 2, 2001). "Death Row deal rejected". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve; Maurice Possley (January 12, 2003). "Decision day for 156 inmates". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Pallasch, Abdon M., Annie Sweeney, and Carlos Sadovi (January 12, 2003). "Gov. Ryan empties Death Row of all 167 – Blanket clemency expected to have sweeping impact". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mills, Steve; Possley, Maurice (January 10, 2003). "Ryan to pardon 4 on Death Row". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Ryan To Pardon 4 Tied To Cop Torture – Death Row inmates say they were coerced into confessing". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. January 10, 2003. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Ruethling, Gretchen (July 22, 2006). "Chicago Mayor Says He Shares Responsibility in Torture Cases". The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Office of Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr. (July 19, 2007). "Daley Culpable in Cop Abuse – Must Explain Himself". US House of Representatives. Archived from the original on October 3, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ Armstrong, Ken; Steve Mills (August 11, 2000). "Justices Reject 6 Death Sentences –– 2 Inmates Get New Hearings on Police Brutality Charges – – Hearing Ordered For DuPage Convict Birkett". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ McKinney, Dave (August 27, 1999). "Death Row inmates win ruling". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (May 30, 2003). "Man freed from Death Row sues city, alleging torture". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "METRO BRIEFS". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. May 30, 2003. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (June 27, 2003). "Ex-Death Row inmate files $30 million suit". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Fuller, Janet Rausa (June 27, 2003). "Freed Death Row inmate files – $30 million suit against Chicago". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Former Death Row inmate files civil rights lawsuit". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. November 25, 2003. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mills, Steve (November 25, 2003). "Pardoned convict files suit alleging torture, cover-up". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Mick Dumke (December 13, 2007). "Hurry Up and Wait". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on December 18, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (January 4, 2008). "Burge victims close to payday – Hurdles to settlement cleared". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "Illinois: Torture Settlement Is Approved". The New York Times. January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Davey, Monica; Catrin Einhorn (December 8, 2007). "Settlement for Torture of 4 Men by Police". The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Chicago: Torture", Shielded from Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States, Human Rights Watch, June 1998; accessed January 14, 2017

- ^ a b c d Sadovi, Carlos (April 25, 2002). "Judge orders torture probe – For years, cop accused of beatings, abuse". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ "Jon Burge and the Legacy of the Chicago Police Department". Chicago Tribune. September 19, 2018.

- ^ Sadovi, Carlos; Secter, Bob (July 20, 2006). "Report: Cops Used Torture". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Sadovi, Carlos (April 25, 2002). "Special prosecutor to probe cop torture". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ "Cop torture probe gets boost from ex-prosecutor". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. March 12, 2003. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ Korecki, Natasha (July 13, 2004). "Burge, 8 others take Fifth on police torture – Current and former cops questioned for upcoming lawsuit". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Korecki, Natasha (September 2, 2004). "Subpoena catches up with Burge". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ Mills, Steve; Maurice Possley (December 2, 2005). "3 cops get immunity in torture case". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ Sweeney, Annie (August 30, 2005). "Global agency asked to probe police torture". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ Ruethling, Gretchen (August 30, 2005). "Midwest: Illinois: Police Torture Accusations". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Davey, Monica (May 20, 2006). "Judge Rules Report on Police in Chicago Should Be Released". The New York Times Company. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Pallasch, Abdon M. (June 21, 2006). "Court clears way for report on cop abuse". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ a b c Rudoren, Judi (July 20, 2006). "Inquiry Finds Police Abuse, but Says Law Bars Trials". The New York Times Company. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Marin, Carol (July 23, 2006). "Burge report doesn't tell whole story". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ "How and Why A Code of Silence Between State's Attorneys and Police Officers Resulted in Unprosecuted Torture". DePaul University. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Conclusions and recommendations of the Committee against Torture: United States of America, unhchr.ch, July 25, 2006.

- ^ Nicodemus, Charles (August 11, 2000). "Cop links 10 capital cases". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Carpenter, John (August 20, 2000). "Former cop accused of torture lies low in Fla". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Adrian, Matt (February 28, 1999). "Forced confessions targeted – Panel favors mandatory police videotaping". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Legislative panel considers requiring videotaped confessions". Courier-News. Newsbank. July 24, 1999. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Ripley, Amanda (November 15, 2004). "Obama's Ascent". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on January 28, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Wills, Christopher (July 18, 2005). "Taped interrogations to begin today". Northwest Herald. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ McKinney, Dave (July 30, 2003). "Governor OK with death penalty reform—almost – Vetoes provision to oust cops but backs rest of legislation". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Blagojevich puts reform on hold". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. July 30, 2003. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Legislative Activity: Illinois, Death Penalty Information Center (2017); accessed January 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c Saulny, Susan; Eric Ferkenhoff (October 21, 2008). "Ex-Officer Linked to Brutality Is Arrested". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ^ "Jon Burge Indictment". Huffington Post. October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Barovick, Harriet (October 23, 2008). "The World". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ^ Main, Franklin (October 21, 2008). "Ex-Chicago cop Burge arrested in torture cases". Chicago Sun-Times. Digital Chicago, Inc. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Dirk (October 29, 2008). "Long Arm of the Law: A Chicago cop is charged with lying about abuse". Newsweek. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ^ United States of America v. Jon Burge, No. 08CR846, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/iln/chicago/2008/pr1021_01a.pdf

- ^ Main, Frank (May 1, 2009). "Burge : I can't get fair trial in Chicago". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ "Burge requests change of venue". Chicago Tribune. May 1, 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ Walberg, Matthew (April 30, 2009). "Convicted murderer gets OK on Burge subpoena". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ "Florida judge refuses to grant Burge subpoena". Chicago Tribune. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ Walberg, Matthew (May 5, 2010). "Jury selection begins in Jon Burge torture trial: Ex-Chicago police detective charged with perjury and obstruction of justice, after allegedly lying about torture of suspects". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "90 Potential Jurors in Jon Burge Case Given Questionnaires". Fox Television Stations, Inc. May 17, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Federal trial of Burge opens with torture allegations". Chicago Tribune. May 26, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ Walberg, Matthew (June 17, 2010). "Feisty, emotional Burge denies torture: Former police commander testifies he's never condoned or witnessed abuse". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 28, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ "Illinois: Ex-Officer Is Questioned About Taking Law Into His Own Hands". The New York Times. June 22, 2010. p. A18. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ Walberg, Matthew; William Lee (June 24, 2010). "Burge case goes to the jury: Defense says accusers conspired on torture claims in prison". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ "No verdict Friday in Burge trial: Deliberations set to resume Monday in case of ex-cop accused of lying about torture". Chicago Tribune. June 25, 2010. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ "Burge found guilty of lying about torture". chicagobreakingnews.com. June 28, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ Sweeney, Annie (January 21, 2011). "Burge given 4 1/2 years in prison: Judge scolds authorities for not putting a stop to alleged torture". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ Warren, James (January 22, 2011). "Burge Case Ends With a Prison Sentence and No Little Bit of Wondering". The New York Times. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "Judge refuses to exit Burge case". Chicago Tribune. January 12, 2011. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ Sweeney, Annie (January 20, 2011). "Burge's sentencing hearing begins today: Former police commander convicted of lying about abuse". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "Jon Burge". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Trymaine (October 3, 2014). "Jon Burge, ex-Chicago cop who ran torture ring, released from prison". MSNBC. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Fretland, Katie; Don Terry (June 25, 2010). "Verdict in Burge Trial Will Not Bring Issue to a Close". The New York Times. p. A25A. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ^ a b Andrew Schroedter"Beyond Burge", Better Government Association, April 5, 2014; accessed January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Steve Bogira, "Torture Commission can only help victims whose torture stemmed from Burge", Chicago Reader, April 5, 2016; accessed January 14, 2017.

- ^ Meisner, Jason (February 20, 2015). "Retired Chicago detective focus of British newspaper investigation". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Man convicted of Gold Coast 'ATM murder' says he was framed". WGN. November 21, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Cate Murphy (February 19, 2015). "The Long Reach of Police Torture: From Chicago to Guantánamo". Colorlines. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

This month, disgraced Chicago police commander Jon Burge walked free with his pension after serving 4 1/2 years for lying under oath. Burge is accused of torturing or overseeing the torture of more than 100 African-American men on the city's South and Westsides throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

- ^ a b "Former Chicago detective tortured Gitmo detainee: investigator". CLTV. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

According to London's Guardian newspaper, there is evidence that former Chicago police detective Richard Zuley – one of commander Jon Burge's men – tortured a detainee at Gimto during an interrogation in 2002.

- ^

Spencer Ackerman (February 18, 2015). "Guantánamo torturer led brutal Chicago regime of shackling and confession". The Guardian. Chicago, IL. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

Chicago has long had an institutional problem with police torture. An infamous former police commander, Jon Burge, used to administer electric shocks to Chicagoans taken into his station, and hit them over the head with telephone books. On Friday, Burge was released from home monitoring, the conclusion of a four and a half-year federal sentence – not for torture, but for perjury.

- ^ "Chicago to pay reparations to police torture victims". USA Today. April 14, 2015.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (April 17, 2015). "Disgraced Chicago cop Jon Burge breaks silence, condemns $5.5 million reparations fund". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015.

- ^ Madhani, Aamer (May 6, 2015). "Chicago City Council approves reparations for police torture victims". USA Today.

- ^ a b c Mills, Steve (May 6, 2015). "Burge reparations deal a product of long negotiations". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Ackerman, Spencer; Stafford, Zach (May 7, 2015). "Victims of Chicago police savagery hope reparations fund is 'beacon' for world". The Guardian. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Davey, Monica; Smith, Mitch (May 6, 2015). "Chicago to Pay $5 Million to Victims of Police Abuse". New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Ken (May 7, 2015). "Chicago Newsroom". YouTube.com. Chicago Access Network Television. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ "Former Chicago Police Cmdr. Jon Burge, tied to torture cases, has died". Chicago Sun-Times. September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Jon Burge, disgraced former CPD commander, dead at 70". ABC Chicago. September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Jon Burge, Disgraced Former Police Commander, Dies at 70". WTTW-TV. September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Jon Burge, alleged ringleader of police torture in Chicago, dies at 70". The Washington Post. September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ "Jon Burge, former Chicago Police commander who routinely tortured Black people, dies". Mic. September 19, 2018.

- ^ Goodman, Jill Laurie (April 16, 2000). "A Disturbing Inquiry into Torture and Human Nature". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ Houlihan, Mary (September 23, 2001). "Family sharpens filmmakers' focus". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Evil With Power: Id's New Series Untouchable: Power Corrupts Delves Into The Dark Underbelly Of Authority". Discovery Press Web. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

General and cited references

[edit]- Conroy, John, Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People: The Dynamics of Torture; ISBN 0-520-23039-6, University of California Press, 2001.

External links

[edit]- Police Torture in Chicago: An archive of articles by John Conroy on police torture, Jon Burge, and related issues, Chicago Reader; accessed June 6, 2018.

- Jon Burge articles in the archive of the Chicago Tribune

- Jon Burge article archive at The Chicago Syndicate

- Trial Begins for Ex-Chicago Police Lt. Accused of Torturing More than 100 African American Men – video report by Democracy Now!

- Video: Jury Convicts Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge of Lying About Torture

- Official Misconduct, law.northwestern.edu; accessed January 10, 2024.

KSF

KSF