Judges 1

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

| Judges 1 | |

|---|---|

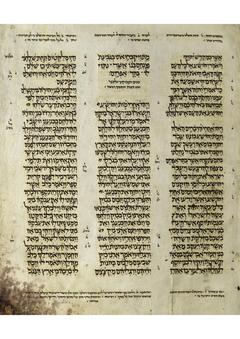

Beginning of Judges in the Aleppo Codex, a 10th-century CE Hebrew manuscript | |

| Book | Book of Judges |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 2 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament (Heptateuch) |

| Order in the Christian part | 7 |

Judges 1 is the first chapter of the Book of Judges, the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, a sacred text in Judaism and Christianity. With the exception of the first verse, scholars have long recognised and studied the parallels between chapter 1 of Judges and chapters 13 to 19 in the preceding Book of Joshua.[1] Both provide similar accounts of the purported conquest of Canaan by the ancient Israelites. Judges 1 and Joshua 15–19 present two accounts of a slow, gradual, and only partial conquest by individual Israelite tribes, marred by defeats, in stark contrast with the 10th and 11th chapters of the Book of Joshua, which portray a swift and complete victory of a united Israelite army under the command of Joshua.[2]

Text

[edit]This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 36 verses.

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[3] Fragments containing parts of this chapter in Hebrew were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls including XJudges (XJudg, X6, 4QJudgc?; 50 BCE) with extant verses 10–12.[4][5][6]

Extant ancient manuscripts of a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint (originally was made in the last few centuries BCE) include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[7][a]

Analysis

[edit]Content

[edit]Overview

[edit]Judges 1 narrates how the Tribe of Judah, which would later establish the southern Kingdom of Judah, took the initiative and was most successful in conquering lands from the Canaanites, while especially those tribes who later formed the northern Kingdom of Israel experienced several failures, with the Canaanites repelling Israelite attacks on their cities.[1][9] Verses 17–36 of Judges 1 include a list of Canaanite cities which were or were not captured as a result of the failures and successes of the military campaigns of the various Israelite tribes in their attempts to conquer Canaan. In most cases of failure, Judges 1 says that the Israelite tribes later subjugated the Canaanites into forced labour.[note 1] According to Judges 2:1–5 and onwards, the Israelite god Yahweh inflicted the later tribulations in Judges upon the (northern) Israelites partially because they failed to completely extinguish the Canaanite race despite his somewhat genocidal command to the contrary.[1][9][10] Compared to the other tribes, the Judahites[note 2] are portrayed as supremely capable conquerors, and even where Judah fails, an excuse is given – the occupants had iron chariots. Hence, many biblical critics see the list as biased, and partly deliberate propaganda, by an author hailing from the Kingdom of Judah.[1][9]

Tribes mentioned

[edit]One curious feature of the list is that it mentions eleven Israelite tribes, namely Kayin (the Kenites), Simeon, Judah, Caleb, Benjamin, Manasseh, Ephraim, Zebulun, Asher, Napthali, and Dan. This set of eleven is not only at odds with the traditional idea that there were Twelve Tribes of Israel, but also with the fact that Kayin and Caleb have never been recognised as sons of Jacob, and do not appear in any other lists of Israelite tribes either.[11] Judges 1 does not specify the total number of tribes, nor mentions the (usually included) tribes of Levi (the landless priestly class), nor Issachar, nor Gad, nor Reuben. The fact that the Rechabites and the Jerahmeelites are also presented as Israelite tribes elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible led scholars such as Max Weber (in Ancient Judaism) and Ronald M. Glassman (2017) to conclude that there never was a fixed number of tribes. Instead, the idea that there were always twelve tribes should be regarded as part of the Israelite national founding myth: the number 12 was not a real number, but an ideal number, which had symbolic significance in Near Eastern cultures with duodecimal counting systems, from which inter alia the modern 12-hour clock is derived.[11]

Conquest of Jerusalem

[edit]Another unusual feature is the conquest of Jerusalem as described in Judges 1:7–8: the Judahites capture Adoni-Bezek and take him to Jerusalem, everyone there was killed and the city burnt to the ground. In contrast, Judges 1:21 reports Jerusalem as having not been conquered and containing Jebusites to this day (confirmed by Joshua 15:63). Judges 19:11–12 again claims it is a city of Jebusites, with no Israelites. Later on in 2 Samuel 5:6–10, David even had to capture Jerusalem from the Jebusites in order to make it his capital.[12] Throughout the centuries, various Christian editions of the Bible sought to resolve this problem in numerous ways, including implying that verse 8 referred to an earlier successful Judahite attack on Jerusalem, but that the city was lost again to the Jebusites later on; or that verse 8 merely describes a siege, not a capture; or that the Judahites only seized the civilian part of the city, but the Jebusites held out in Jerusalem's castle or fortress until David finally took it.[12]

While Joshua 5:13–6:27 narrates the Battle of Jericho as the iconic first victory in the conquest of Canaan, Judges 1 does not even mention Jericho, although some Bible translations identify the "City of Palms" mentioned in Judges 1:16 with Jericho. Even so, the verse does not indicate the city was taken by military force, nor is it the first city the Israelites conquered according to Judges 1, which starts with the defeat of king Adoni-Bezek of the unidentified place "Bezek" (Judges 1:4–7), after which Jerusalem was supposedly taken and sacked (Judges 1:8).[13]

Hebrew/Greek contradiction on Judges 1:18

[edit]

According to the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) of Judges 1:18, "Also Judah took Gaza with the coast thereof, and Askelon with the coast thereof, and Ekron with the coast thereof." (King James Version).[note 4] However, the Greek Septuagint (LXX) renders Judges 1:18 as: "But Judas did not inherit Gaza nor her coasts, nor Ascalon nor her coasts, nor Accaron nor her coasts, nor Azotus nor the lands around it.' (Brenton's Septuagint Translation).[15][note 3]

This contradiction has puzzled scholars, as not only does the Greek text add Ashdod (Azotus) to the list of cities, but it specifically denies that the Judahites conquered (literally "inherited") these cities, while the Hebrew text asserts that they did.[17][18] Although English Bible translations have generally followed the Masoretic Text in saying the Judahites took the three cities,[19] some scholars claim that the Greek version should be regarded as superior if the inhabitants of these four coastal cities are to be equated with "the people of the plains" in the next verse, who repelled the Judahites thanks to their iron chariots.[20] The Septuagint may therefore 'correct' the Hebrew text, as other textual evidence also seems to indicate the towns did not fall to the Israelites until much later.[17][21] Charles Ellicott noted that Josephus had a different solution, claiming in Antiquities of the Jews (volume 2, paragraph 4) that 'Askelon and Ashdod were taken in the war, but that Gaza and Ekron escaped, because their situation in the plains enabled them to use their chariots; yet in 3, § 1, he says that the Canaanites re-conquered Askelon and Ekron.'[17]

Composition and historicity

[edit]David M. Gunn (2005) noted that early Jewish and Christian interpreters paid little attention to Judges 1–2, but by the 18th century, scholars had begun to consider the discrepancies between the books of Joshua and Judges a problem.[12] While Joshua 10–11 portrayed Joshua's united Israelites as completely annihilating all Canaanites and capturing or destroying all their cities, Judges 1 shows many of these cities as still standing and being inhabited by Canaanites who often successfully repelled various Israelite tribes.[12] For example, Voltaire (1776), invoking earlier observations made by Thomas Woolston, argued that either the Book of Joshua or the Book of Judges had to be false, as 'this crowd of contradictions is unsustainable.'[12]

George Foot Moore (1895) argued that Judges 1's account of the Israelite conquest of Canaan was 'of vastly greater historical value' than Joshua 10–11, as a 'gradual and partial' subjugation of the land was consistent with everything else known about subsequent Israelite and Canaanite history in the centuries thereafter, while 'the whole political and religious history of these centuries would be unintelligible if we were to imagine it as beginning with such a conquest of Canaan as narrated in the Book of Joshua'.[2] G. Ernest Wright (1946) stated that, in his day, textual critics generally believed that Judges 1 was probably mostly written in the 10th or 9th century BCE (with verse 1 "After the death of Joshua..." 'having been added by a harmonistic editor') and 'supported by statements in Joshua 15–19', while Joshua 10 was written much later by the Deuteronomist (c. 6th century BCE) and was therefore considered unreliable.[2] However, Wright contended that his colleagues too readily wrote off Joshua 10–11 as unhistorical due to focusing on verses 10:40–41: 'Undoubtedly it was an exaggeration to say that every single inhabitant was killed. (...) Reduce the statement to geography, and all that it claims is that Joshua took the Judean hill country with the Negeb and Shephela.'[2] He also accused Moore and other scholars of oversimplifying the reliability of Judges 1, as it is often fragmentary, self-contradictory, and 'not in such absolute contradiction to Joshua and the Deuteronomic point of view as is so commonly assumed.'[2]

A. Graeme Auld (1998) concluded that Judges 1 was not an early document, but composed on the basis of several notes scattered throughout the Book of Joshua, and that the author attributes the northern tribes' troubled history to their failures during the conquest period.[10] Similarly, K. Lawson Younger (1995) made the case that the composition of Judges 1 was dependent on text taken from Joshua 13–19 and reused for the author's own purposes: 'Judges 1 recapitulates, recasts and extends the story of the process of Israel's taking possession of the land of Canaan. It utilizes materials from the book of Joshua (esp. Joshua 13–19) with some expansions to explicitly reflect the general success of Judah and the increasing failure of the other Israelite tribes, especially Dan.'[1] Younger therefore cautioned against taking Judges 1 as historically reliable just because it seems more credible than Joshua 10–11, because Judges 1 shows clear signs of deliberately twisting the material of Joshua 13–19 in favor of Judah and Joseph at the expense of the other Israelite tribes, and attributes the latter's failures to moral degeneration.[1] More recently, Koert van Bekkum (2012) argued that archaeological evidence indicates that Judges 1 best reflects the historical and geographical realia of Canaan during the 12th-11th centuries BCE, suggesting that the text preserves historical memories from this period.[22]

Potential pro-Judah bias

[edit]Some scholars such as Marc Zvi Brettler have concluded that Judges 1 is a pro-Judean[note 2] redaction of Joshua 13–19, but K. Lawson Younger noted that even Judah is subtly criticised in Judges 1, and the rest of the Book of Judges portrays Judah in the same negative manner as all other tribes, and it looked to him like the first three chapters of Judges are integral parts of the book that were not added by later editors.[1] Gregory T.K. Wong (2005) mounted an argument against commonly-cited evidence for a pro-Judah polemic in all of Judges, but Serge Frolov (2007) sought to refute his interpretations, concluding: 'The opening chapter of Judges presents Judah as uniquely capable of mounting a successful war effort on behalf of the entire Israel (...). In sum, according to Judges Judah is supremely qualified to be in charge of a political entity that includes all tribes of Israel, in other words, of the Israelite monarchy. This stance is in its turn consistent with the Deuteronomistic political philosophy, hinging upon the idea that only the Judahite Davidic dynasty is entitled to reign in Israel (2 Samuel 7) and viewing the Northern Kingdom (whose mainstay was the house of Joseph) as a renegade province (see especially 2 Kings 17,21–23).'[9]

List of cities

[edit]- This is not a list of archaeological remains in the modern-day Middle East. This discusses a specific list present in the Bible.

Successes

[edit]The Tribe of Judah took:

- The hill country, the Negev and the western foothills (Judges 1:9; Judges 1:19)

- Gaza, Ascalon and Ekron (according to the Hebrew Masoretic Text of Judges 1:18, see above[17])

- Hebron (Kiriath Arba), where Caleb drives out the three sons of Anak (Judges 1:20)

- Debir (Kiriath Sepher), taken by Othniel (Judges 1:11–13)

The Tribe of Simeon together with that of Judah destroy:

The Tribes of Joseph (consisting of two "half-tribes": the Tribe of Ephraim and the Tribe of Manasseh) took:

- Bethel, killing all inhabitants except for the man and his family who showed them how to get into the city (1:22–26)

Failures

[edit]Because the inhabitants had iron chariots, the Tribe of Judah failed to take:

- Gaza, Ascalon, Ekron and Ashdod (according to the Greek Septuagint version of Judges 1:18, see above[17])

- The plains (Judges 1:19)

The Tribe of Benjamin failed to drive out the occupants of:

- Jerusalem (also known as Jebus) (Judges 1:21). However, Judges 1:8 reported that the Judahites had (already?) taken Jerusalem, killed everyone inside and burnt it.[12]

The Tribe of Manasseh failed to drive out the Canaanites from:

- Beit She'an (Judges 1:27)

- Taanach (Judges 1:27)

- Dor (Judges 1:27)

- Ibleam (Judges 1:27)

- Megiddo (Judges 1:27)

The Tribe of Ephraim was unable to drive out the Canaanites from:

- Gezer (Judges 1:29)

The Tribe of Zebulun was unable to drive out the Canaanites from:

The Tribe of Asher was unable to drive out the Canaanites from:

- Akko (Judges 1:31)

- Siddon (Judges 1:31)

- Ahlab (Judges 1:31)

- Aczib (Judges 1:31)

- Helbah (Judges 1:31)

- Aphek (Judges 1:31)

- Rehob (Judges 1:31)

The Tribe of Naphtali was unable to drive out the Canaanites living in:

- Beth Shemesh (Judges 1:33)

- Beth Anath (Judges 1:33)

The Tribe of Dan was confined to the hill country by the Amorites and could not capture:

- Mount Heres (Judges 1:34–35)

- Aijalon (Judges 1:34–35)

- Shaalbim (Judges 1:34–35).

Notes

[edit]- ^ Judges 1:28 makes the general claim that 'When Israel became strong, they pressed the Canaanites into forced labor but never drove them out completely.' (NIV) Verses 30, 33, and 35 mention specific examples of Canaanite tribes which were subjected to forced labour.

- ^ a b The terms 'Judahite' and 'Jud(a)ean' are synonymous adjectives for 'Judah'. The former is based on the Hebrew Yehudah (see Kingdom of Judah), while the latter is derived from the Latinised form Iudaea (see Judea (Roman province)). Scholars prefer the term 'Judahite' when referring to the pre-Roman period.

- ^ a b καὶ οὐκ ἐκληρονόμησεν Ἰούδας τὴν Γάζαν οὐδὲ τὰ ὅρια αὐτῆς, οὐδὲ τὴν Ἀσκάλωνα οὐδὲ τὰ ὅρια αὐτῆς, οὐδὲ τὴν Ἀκκαρὼν οὐδὲ τὰ ὅρια αὐτῆς, οὐδὲ τὴν Ἄζωτον οὐδὲ τὰ περισπόρια αὐτῆς. (Swete's Septuagint). The word 'οὐκ' means "not", 'ἐκληρονόμησεν' (related to the modern Greek verb κληρονομώ) means "inherit", and 'οὐδὲ' means "nor".[16]

- ^ וַיִּלְכֹּ֤ד יְהוּדָה֙ אֶת־עַזָּ֣ה וְאֶת־גְּבוּלָ֔הּ וְאֶֽת־אַשְׁקְלֹ֖ון וְאֶת־גְּבוּלָ֑הּ וְאֶת־עֶקְרֹ֖ון וְאֶת־גְּבוּלָֽהּ׃. (Westminster Leningrad Codex).[14]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The whole book of Judges is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Younger, Jr., K. Lawson (1995). "The Configuring of Judicial Preliminaries: Judges 1.1-2.5 and Its Dependence On the Book of Joshua". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 20 (68). SAGE Publishing: 75–87. doi:10.1177/030908929502006805. S2CID 170339976.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, G. Ernest (1946). "The Literary and Historical Problem of Joshua 10 and Judges 1". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 5 (2). University of Chicago Press: 105–114. doi:10.1086/370775. JSTOR 542372. S2CID 161249981. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Ulrich 2010, p. 254.

- ^ Dead sea scrolls - Judges

- ^ Fitzmyer 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b c d Frolov, Serge (2007). "Fire, Smoke, and Judah in Judges: A Response to Gregory Wong". Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament. 21 (1). Taylor & Francis: 127–138. doi:10.1080/09018320601171005. S2CID 159653915.

- ^ a b Klein, Ralph W. (2001). "Joshua Retold: Synoptic Perspectives by A. Graeme Auld". Journal of Biblical Literature. 120 (4). Society of Biblical Literature: 747. doi:10.2307/3268272. JSTOR 3268272. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ a b Glassman, Ronald M. (2017). "Israelite Tribal Confederation Enters Canaan". The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States. Cham: Springer. p. 632. ISBN 978-3-319-51695-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Gunn, David M. (2005). Judges Through the Centuries. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-0-631-22252-1.

- ^ "Judges 1 NIV". biblehub.com. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Judges 1:18 Hebrew Text Analysis". Biblehub.com. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Judges 1 Brenton's Septuagint Translation". Biblehub.com. 1844. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Judges 1 Swete's Septuagint". Biblehub.com. 1930. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Judges 1:18 Commentaries". Biblehub.com. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Brug, John Frederick (1978). A Literary and Archaeological Study of the Philistines, Issues 265–266. British Archaeological Reports. p. 6. ISBN 9780860543374. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Judges 1:18 Parallel". Biblehub.com. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Volumes 22-24. American Research Center in Egypt. 1985. p. 212. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

Judges 1: 18-19 may be an indication, especially if the Septuagint version of Judges 1:18 is taken as superior to the Masoretic text, i.e., that the Israelites were unable to take the valleys and towns, specifically Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ekron, because the Canaanites had chariots of iron.

- ^ Dothan, Trude; Dothan, Moshe (1992). People of the Sea: The Search for the Philistines. Macmillan. p. 235. ISBN 9780025322615. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ van Bekkum, Koert (2012). "Coexistence as Guilt: Iron I Memories in Judges 1". In Galil, Gershon; Leṿinzon-Gilboʻa, Ayelet; Maeir, Aren M.; Kahn, Dan'el (eds.). The Ancient Near East in the 12th-10th Centuries BCE: Culture and History : Proceedings of the International Conference, Held at the University of Haifa, 2-5 May, 2010. Alter Orient und Altes Testament. Vol. 392. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 525–548. ISBN 978-3-86835-066-1.

Sources

[edit]- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195288810.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802862419.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300188271.

- Niditch, Susan (2007). "10. Judges". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 176–191. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Ulrich, Eugene, ed. (2010). The Biblical Qumran Scrolls: Transcriptions and Textual Variants. Brill.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jewish translations:

- Shoftim - Judges - Chapter 1 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Judges chapter 1. Bible Gateway

KSF

KSF