Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 47 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 47 min

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji | |

|---|---|

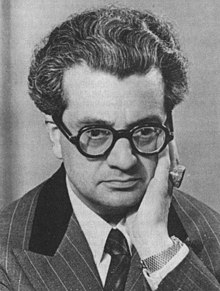

Sorabji in 1917 | |

| Born | Leon Dudley Sorabji 14 August 1892 Chingford, Essex, England |

| Died | 15 October 1988 (aged 96) Winfrith Newburgh, Dorset, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (born Leon Dudley Sorabji; 14 August 1892 – 15 October 1988) was an English composer, music critic, pianist and writer whose music, written over a period of seventy years, ranges from sets of miniatures to works lasting several hours. One of the most prolific 20th-century composers, he is best known for his piano pieces, notably nocturnes such as Gulistān and Villa Tasca, and large-scale, technically intricate compositions, which include seven symphonies for piano solo, four toccatas, Sequentia cyclica and 100 Transcendental Studies. He felt alienated from English society by reason of his homosexuality and mixed ancestry, and had a lifelong tendency to seclusion.

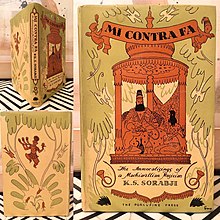

Sorabji was educated privately. His mother was English and his father a Parsi businessman and industrialist from India, who set up a trust fund that freed his family from the need to work. Although Sorabji was a reluctant performer and not a virtuoso, he played some of his music publicly between 1920 and 1936. In the late 1930s, his attitude shifted and he imposed restrictions on performance of his works, which he lifted in 1976. His compositions received little exposure in those years and he remained in public view mainly through his writings, which include the books Around Music and Mi contra fa: The Immoralisings of a Machiavellian Musician. During this time, he also left London and eventually settled in the village of Corfe Castle, Dorset. Information on Sorabji's life, especially his later years, is scarce, with most of it coming from the letters he exchanged with his friends.

As a composer, Sorabji was largely self-taught. Although he was attracted to modernist aesthetics at first, he later dismissed much of the established and contemporary repertoire. He drew on such diverse influences as Ferruccio Busoni, Claude Debussy and Karol Szymanowski and developed a style blending baroque forms with frequent polyrhythms, interplay of tonal and atonal elements and lavish ornamentation. Though he composed mostly for the piano and has been likened to the composer-pianists he admired, including Franz Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan, he also wrote orchestral, chamber and organ pieces. His harmonic language and complex rhythms anticipated works from the mid-20th century onwards, and while his music remained largely unpublished until the early 2000s, interest in it has grown since then.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji was born in Chingford, Essex (now Greater London), on 14 August 1892.[1] His father, Shapurji Sorabji[n 1] (1863–1932), was a Parsi civil engineer born in Bombay, India. Like many of his near ancestors, he was an industrialist and businessman.[3] Sorabji's mother, Madeline Matilda Worthy (1866–1959), was English and born in Camberwell, Surrey (now South London).[4] She is said to have been a singer, pianist and organist, but there is little evidence of this.[5] They married on 18 February 1892 and Sorabji was their only child.[2]

Little is known of Sorabji's early life and musical beginnings. He reportedly started to learn the piano from his mother when he was eight,[6] and he later received help from Emily Edroff-Smith, a musician and piano teacher who was a friend of his mother's.[7][8] Sorabji attended a school of about twenty boys where, in addition to general education, he took music lessons in piano, organ and harmony, as well as language classes for German and Italian.[9] He was also educated by his mother, who took him to concerts.[10]

Entering the music world (1913–1936)

[edit]The first major insight into Sorabji's life comes from his correspondence with the composer and critic Peter Warlock, which began in 1913. Warlock inspired Sorabji to become a music critic and focus on composition. Sorabji had obtained a matriculation but decided to study music privately, as Warlock's claims about universities made him abandon his plan of going to one.[6][11][12] Thus, from the early 1910s until 1916, Sorabji studied music with the pianist and composer Charles A. Trew.[13] Around this time, he came to be close to and exchanged ideas with the composers Bernard van Dieren and Cecil Gray, who were friends with Warlock.[14] For unknown reasons, Sorabji was not conscripted during World War I, and though he later praised conscientious objectors for their courage, there is no proof he tried to register as one.[15]

Sorabji's letters from this time document his nascent feelings of otherness, the sense of alienation that he as a homosexual of mixed ancestry experienced and his development of a non-English identity.[16] Sorabji joined the Parsi community in 1913 or 1914 by attending a Navjote ceremony (probably performed in his home by a priest) and changed his name.[17][n 2] He had apparently been mistreated by other boys in the school he attended and his tutor, who sought to make an English gentleman out of him, would make derogatory comments about India and hit him on the head with a large book, which gave him recurring headaches. Sorabji said that in 1914, a "howling mob" with brickbats and large stones pursued him and "half killed" him.[22] These experiences have been identified as the root of his dislike of England,[9][n 3] and he was soon to describe English people as intentionally and systematically mistreating foreigners.[22]

In late 1919, Warlock sent the music critic Ernest Newman several of Sorabji's scores, including his First Piano Sonata. Newman ignored them, and in November that year, Sorabji privately met the composer Ferruccio Busoni and played the piece for him. Busoni expressed reservations about the work but gave him a letter of recommendation, which helped Sorabji get it published.[24] Warlock and Sorabji then publicly accused Newman of systematic avoidance and sabotage, which led the critic to detail why he could not meet Sorabji or review his scores. Warlock proceeded to call Newman's behaviour abusive and stubborn, and the issue was settled after the journal Musical Opinion reproduced correspondence between Sorabji and Newman.[25]

Sorabji has been called a late starter, as he had not composed music before the age of 22.[5] Already before picking up the craft of composition, he had been drawn to recent developments in art music at a time when they did not receive much attention in England. This interest, along with his ethnicity, cemented his reputation as an outsider.[26] The modernist style, increasingly longer durations and technical complexity of his works baffled critics and audiences.[27][28] Although his music had its detractors, some musicians received it positively:[29] after hearing Sorabji's Le jardin parfumé—Poem for Piano Solo in 1930, the English composer Frederick Delius sent him a letter admiring the piece's "real sensuous beauty",[30][31] and around the 1920s, the French pianist Alfred Cortot[32] and the Austrian composer Alban Berg took an interest in his work.[33]

Sorabji first played his music publicly in 1920 and he gave occasional performances of his works in Europe over the next decade.[34] In the mid-1920s, he befriended the composer Erik Chisholm, which led to the most fruitful period of his pianistic career. Their correspondence began in 1926 and they first met in April 1930 in Glasgow, Scotland. Later that year, Sorabji joined Chisholm's recently created Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music,[35] whose concerts featured a number of distinguished composers and musicians. Despite Sorabji's protestations that he was "a composer—who incidentally, merely, plays the piano",[36] he was the guest performer to make the most appearances in the series.[37][38] He came to Glasgow four times and played some of the longest works he had written to date: he premiered Opus clavicembalisticum and his Fourth Sonata[n 4] in 1930 and his Toccata seconda in 1936, and he gave a performance of Nocturne, "Jāmī" in 1931.[34][39]

Years of seclusion

[edit]Ups and downs in life and music (1936–1949)

[edit]On 10 March 1936 in London, the pianist John Tobin played a portion of Opus clavicembalisticum. The performance lasted 90 minutes—twice as long as it should have.[n 5] Sorabji left before it finished and denied having attended, paid for, or supported the performance.[41] A number of leading critics and composers attended the concert and wrote negative critiques in the press, which severely damaged Sorabji's reputation.[42] Sorabji gave the premiere of his Toccata seconda in December 1936, which became his last public appearance. Three months earlier, he had said he was no longer interested in performances of his works, and over the next decade, made remarks expressing his opposition to the spread of his music.[34][43]

Sorabji eventually placed restrictions on performances of his works. These became known as a "ban", but there was no official or enforceable pronouncement to this effect; rather, he discouraged others from playing his music publicly. This was not without precedent and even his first printed scores bore a note reserving the right of performance.[44] Few concerts with his music—most of them semi-private or given by his friends and with his approval—took place in those years, and he turned down offers to play his works in public.[45] His withdrawal from the world of music has usually been ascribed to Tobin's recital,[46] but other reasons have been put forward for his decision, including the deaths of people he admired (such as Busoni) and the increasing prominence of Igor Stravinsky and twelve-tone composition.[47] Nonetheless, the 1930s marked an especially fertile period in Sorabji's career: he created many of his largest works[48] and his activity as a music critic peaked. In 1938, Oxford University Press became the agent for his published works until his death in 1988.[49]

A major factor in Sorabji's change of attitude was his financial situation. Sorabji's father had returned to Bombay after his marriage in 1892, where he played an important role in the development of India's engineering and cotton machinery industries. He was musically cultured and financed the publication of 14 of Sorabji's compositions between 1921 and 1931,[27] although there is little evidence that he lived with the family, and he did not want his son to become a musician.[1][50] In October 1914, Sorabji's father set up the Shapurji Sorabji Trust, a trust fund that would provide his family with a life income that would free them of the need to work.[51] Sorabji's father, affected by the fall of the pound and rupee in 1931, stopped supporting the publication of Sorabji's scores that same year,[52] and died in Bad Nauheim, Germany, on 7 July 1932. Following an initial trip to India, Sorabji's second one (lasting from May 1933 to January 1934)[53] revealed that his father had been living with another woman since 1905 and had married her in 1929.[54] Sorabji and his mother were excluded from his will and received a fraction of what his Indian heirs did.[55] An action was instituted around 1936 and the bigamous marriage was declared null and void by a court in 1949, but the financial assets could not be retrieved.[56][57][n 6]

Sorabji countered the uncertainty that he experienced during this time by taking up yoga.[58] He credited it with helping him command inspiration and achieve focus and self-discipline, and wrote that his life, once "chaotic, without form or shape", now had "an ordered pattern and design".[59] The practice inspired him to write an essay titled "Yoga and the Composer" and compose the Tāntrik Symphony for Piano Alone (1938–39), which has seven movements titled after bodily centres in tantric and shaktic yoga.[60]

Sorabji did not perform military or civic duties during World War II, a fact that has been attributed to his individualism. His open letters and music criticism did not cease, and he never touched the topic of war in his writings.[61] Many of Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Studies (1940–1944) were written during German bombings, and he composed during the night and early morning in his home at Clarence Gate Gardens (Marylebone, London) even as most other blocks were abandoned. Wartime records show that a high explosive bomb hit Siddons Lane, where the back entrance to his former place of residence is located.[62]

Admirers and inner withdrawal (1950–1968)

[edit]

In 1950, Sorabji left London, and in 1956, he settled in The Eye,[n 7] a house that he had built for himself in the village of Corfe Castle, Dorset.[64] He had been on holidays in Corfe Castle since 1928 and the place had appealed to him for many years.[65] In 1946, he expressed the desire to be there permanently, and once settled in the village, he rarely ventured outside.[66] While Sorabji felt despised by the English music establishment,[67] the main target of his ire was London, which he called the "International Human Rubbish dump"[68] and "Spivopolis" (a reference to the term spiv).[65][69] Living expenses also played a role in his decision to leave the city.[65] As a critic, he earned no money,[51] and while his lifestyle was modest, he sometimes found himself in financial difficulties.[70] Sorabji had a strong emotional attachment to his mother, which has been partly attributed to being abandoned by his father and the impact this had on their financial security.[10] She accompanied him on his travels and he spent nearly two-thirds of his life with her until the 1950s.[71] He also looked after his mother in her last years when they were no longer together.[72]

Despite his social isolation and withdrawal from the world of music, Sorabji retained a circle of close admirers. Concerns over the fate of his music gradually intensified, as Sorabji did not record any of his works and none of them had been published since 1931.[73] The most ambitious attempt to preserve his legacy was initiated by Frank Holliday, an English trainer and teacher who met Sorabji in 1937 and was his closest friend for about four decades.[1][74] From 1951 to 1953, Holliday organised the presentation of a letter inviting Sorabji to make recordings of his own music.[75] Sorabji received the letter, signed by 23 admirers, soon after, but made no recordings then, in spite of the enclosed cheque for 121 guineas (equivalent to £4,481 in 2023[n 8]).[76] Sorabji was concerned by the impact copyright laws would have on the spread of his music,[77] but Holliday eventually persuaded him after years of opposition, objections and stalling. A little over 11 hours of music were recorded in Sorabji's home between 1962 and 1968.[78] Although the tapes were not intended for public circulation, leaks occurred and some of the recordings were included in a 55-minute WBAI broadcast from 1969 and a three-hour programme produced by WNCN in 1970. The latter was broadcast several times in the 1970s and helped in the dissemination and understanding of Sorabji's music.[79]

Sorabji and Holliday's friendship ended in 1979 because of a perceived rift between them and disagreements over custodianship of Sorabji's legacy.[80] Unlike Sorabji, who proceeded to destroy much of their correspondence, Holliday preserved his collection of Sorabji's letters and other related items, which is one of the largest and most important sources of material on the composer.[81] He took many notes during his visits to Sorabji and often accepted everything he told him at face value.[82] The collection was purchased by McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) in 1988.[83]

Another devoted admirer was Norman Pierre Gentieu, an American writer who discovered Sorabji after reading his book Around Music (1932).[1] Gentieu sent Sorabji some provisions in response to post-war shortages in England, and he continued to do so for the next four decades. In the early 1950s, Gentieu offered to pay for the expenses to microfilm Sorabji's major piano works and provide copies to selected libraries.[84][85] In 1952, Gentieu set up a mock society (the Society of Connoisseurs) to mask the financial investment on his part, but Sorabji suspected that it was a hoax. Microfilming (which encompassed all of Sorabji's unpublished musical manuscripts) began in January 1953 and continued until 1967 as new works were produced.[86] Copies of the microfilms became available in several libraries and universities in the United States and South Africa.[84]

Over the years, Sorabji grew increasingly tired of composition; health problems,[n 9] stress and fatigue interfered and he began to loathe writing music. After the Messa grande sinfonica (1955–61)—which comprises 1,001 pages of orchestral score[90]—was completed, Sorabji wrote he had no desire to continue composing, and in August 1962, he suggested he might abandon composition and destroy his extant manuscripts. Extreme anxiety and exhaustion caused by personal, family and other issues, including the private recordings and preparing for them, had drained him and he took a break from composition. He eventually returned to it, but worked at a slower pace than before and produced mostly short works. In 1968, he stopped composing and said he would not write any more music. Documentation of how he spent the next few years is unavailable and his production of open letters declined.[91]

Renewed visibility (1969–1979)

[edit]In November 1969, the composer Alistair Hinton, then a student at the Royal College of Music in London, discovered Sorabji's music in the Westminster Music Library and wrote a letter to him in March 1972.[92] They met for the first time in Sorabji's home on 21 August 1972 and quickly became good friends;[93] Sorabji began to turn to Hinton for advice on legal and other matters.[94] In 1978, Hinton and the musicologist Paul Rapoport microfilmed Sorabji's manuscripts that did not have copies made, and in 1979 Sorabji wrote a new will that bequeathed Hinton (now his literary and musical executor) all the manuscripts in his possession.[95][n 10] Sorabji, who had not written any music since 1968, returned to composition in 1973 owing to Hinton's interest in his work.[98] Hinton also persuaded Sorabji to give Yonty Solomon permission to play his works in public, which was granted on 24 March 1976 and marked the end of the "ban", although another pianist, Michael Habermann, may have received tentative approval at an earlier date.[99][100] Recitals with Sorabji's music became more common, leading him to join the Performing Right Society and derive a small income from royalties.[101][n 11]

In 1977, a television documentary on Sorabji was produced and broadcast. The images in it consisted mostly of still photographs of his house; Sorabji did not wish to be seen and there was just one brief shot of him waving to the departing camera crew.[102][103] In 1979, he appeared on BBC Scotland for the 100th birthday of Francis George Scott, and on BBC Radio 3 to commemorate Nikolai Medtner's centenary. The former broadcast led to Sorabji's first meeting with Ronald Stevenson, whom he had known and admired for more than 20 years.[104] Shortly after, Sorabji received a commission from Gentieu (who acted on behalf of the Philadelphia branch of the Delius Society) and fulfilled it by writing Il tessuto d'arabeschi (1979) for flute and string quartet. He dedicated it "To the memory of Delius" and was paid £1,000 (equivalent to £6,390 in 2023[n 8]).[105]

Last years

[edit]

Sorabji completed his final piece, Due sutras sul nome dell'amico Alexis, in 1984,[106] and stopped composing afterwards because of his failing eyesight and struggle to physically write.[107] His health deteriorated severely in 1986, which obliged him to abandon his home and spend several months in a Wareham hospital; in the October of that year, he put Hinton (his sole heir) in charge of his personal affairs.[1][99] By this time, the Shapurji Sorabji Trust had been exhausted[108] and his house, along with his belongings (including some 3,000 books), was put up for auction in November 1986.[109] In March 1987, he moved into Marley House Nursing Home, a private nursing home in Winfrith Newburgh (near Dorchester, Dorset), where he was permanently chairbound and received daily nursing care.[110] In June 1988, he suffered a mild stroke, which left him slightly mentally impaired. He died of heart failure and arteriosclerotic heart disease on 15 October 1988 at the age of 96. He was cremated in Bournemouth Crematorium on 24 October, and the funeral service took place in Corfe Castle in the Church of St. Edward, King and Martyr, on the same day.[111] His remains are buried in "God's Acre", the Corfe Castle cemetery.[112]

Personal life

[edit]Myths and reputation

[edit]

During Sorabji's lifetime and since his death, myths about him have circulated. To dispel them, scholars have focused on his compositional method,[113] his skills as a performer,[113] the dimensions and complexity of his pieces[114] and other topics.[115] It has proven to be a challenging task: while nearly all of Sorabji's known works have been preserved and there are almost no lost manuscripts,[116] few documents and items relating to his life have survived. His correspondence with his friends is the main source of information on this area, though much of it is missing, as Sorabji often discarded large volumes of his letters without inspecting their content. Marc-André Roberge, the author of Sorabji's first biography, Opus sorabjianum, writes that "there are years for which hardly anything can be reported".[117]

Sorabji peddled some myths himself. He claimed to have had relatives in the upper echelons of the Catholic Church and wore a ring that he said had belonged to a deceased Sicilian cardinal and would go to the Pope upon his death.[118][119][n 12] The villagers in Corfe Castle sometimes referred to him as "Sir Abji" and "Indian Prince".[120] Sorabji often gave lexicographers incorrect biographical information on himself.[121] One of them, Nicolas Slonimsky, who in 1978 erroneously wrote that Sorabji owned a castle,[122] once called him "the most enigmatic composer now living".[123]

Sorabji's mother had long been believed to have been Spanish-Sicilian, but the Sorabji scholar Sean Vaughn Owen has shown she was born to English parents christened in an Anglican church.[124] He found that she often spread falsehoods[125] and suggested this influenced Sorabji, who made a habit out of misleading others.[126] Owen concludes that despite Sorabji's elitist and misanthropic image, his acquaintances found him serious and stern but generous, cordial and hospitable.[127] He summarises the tensions displayed in Sorabji's reputation, writings, persona and behaviour thus:

The contradictions between his reputation and the actuality of his existence were known to Sorabji and they appear to have given him much amusement. This sense of humour was detected by many in the village, yet they too were prone to believe his stories. The papal connection ... was a particular favourite and as much as Sorabji detested being spotlighted in a large group, he was perfectly content in more intimate situations bringing direct attention to his ring or his thorny attitude regarding the ban on his music.[128]

Sexuality

[edit]

In 1919, Sorabji experienced a "sexual awakening", which led him to join the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology and the English branch of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft.[129] In the early 1920s, at a time of considerable emotional distress, he consulted Havelock Ellis, a writer on sexual psychology, on the matter of his orientation. Ellis held progressive views on the subject and Sorabji inscribed a dedication "To Dr. Havelock Ellis.—in respectful admiration, homage and gratitude" in his Piano Concerto No. 7 (1924).[130][131] He went on to reference Ellis in many of his articles, often building on the concept of sexual inversion.[132]

Although Sorabji's homosexual tendencies were first exhibited in his letters to Warlock in 1914,[133] they manifested most strongly in his correspondence with Chisholm. Sorabji sent him a number of exceptionally long letters that captured a desire for intimacy and to be with him alone, and have been interpreted as expressing Sorabji's love for him.[134] Chisholm got married in 1932 and apparently rebuffed him around this time, after which Sorabji's letters to him became less sentimental and more infrequent.[135]

Sorabji spent approximately the last 35 years of his life with Reginald Norman Best (1909–1988), the son of his mother's friend. Best spent his life savings to help Sorabji buy The Eye and shared the costs of living with him.[136] He was homosexual, and although Sorabji often described him as his godson, many suspected there was more to their relationship and those close to them believed they were partners.[137] Sorabji once called him "one of the two people on earth most precious to me".[138] In March 1987, they moved into Marley House Nursing Home, where Sorabji called him "darling" and complimented him on his looks before Best's death on 29 February 1988, an event described as a blow to the composer.[111] Sorabji suffered a mild stroke in June and died later that year; their ashes are buried beside each other.[139]

Sorabji's writings include Gianandrea and Stephen, a short homoerotic story set in the Italian city of Palermo. Though the text purports to be biographical, Roberge considers most of it a fabrication.[140] He nevertheless argues that Sorabji probably had sexual encounters with men while he lived in London, citing a letter in which he wrote, "deep affection and indeed love between men is the greatest thing in life, at any rate it is in my life".[141][142] He suggests that Sorabji often felt lonely, which led him "to create for himself an ideal world in which he could believe—and have his friends believe".[143]

Social life

[edit]Many of Sorabji's friends were not musicians and he said that their human qualities meant more to him than their musical erudition.[144] He sought warmth in others and said he depended emotionally on his friends' affection. He could be extremely devoted to them, though he admitted to preferring solitude.[145] Some of his friendships, like those with Norman Peterkin or Hinton, lasted until the death of either party; others were broken.[146] Though Sorabji had often reserved harsh words for the English, in the 1950s, he conceded he had not been objective in so doing and acknowledged that many of his close friends were or had been Englishmen.[147]

Best, Sorabji's companion, suffered from depression and multiple congenital deficiencies. Around 1970, he began taking electroconvulsive therapy,[136] which caused him considerable anxiety. Sorabji was upset by this and Owen believes that the treatment and Best's mental health problems exacerbated their reclusiveness.[148] Sorabji cherished his privacy (even describing himself as a "claustrophiliac"[149]) and has often been called a misanthrope.[145] He planted more than 250 trees around his house, which had a number of notices to deter uninvited visitors.[63] Sorabji did not like the company of two or more friends simultaneously and would accept only one at a time, each about once or twice per year.[150] In an unpublished text titled The Fruits of Misanthropy, he justified his reclusiveness by saying, "my own failings are so great that they are as much as I can put up with in comfort—those of other people superadded I find a burden quite intolerable".[151]

Religious views

[edit]Sorabji had an interest in the occult, numerology and related topics; Rapoport suggested that Sorabji chose to hide his year of birth for fear that it could be used against him.[152] Early in his life, Sorabji published articles on the paranormal and he included occult inscriptions and references in his works.[153] In 1922, he met the occultist Aleister Crowley, whom he shortly after dismissed as a "fraud" and "the dullest of dull dogs".[154][155][156] He also maintained a 20-year friendship with Bernard Bromage, an English writer on mysticism.[157] Bromage acted as joint trustee of the Shapurji Sorabji Trust between 1933 and 1941 and produced a defective index for Sorabji's book Around Music, which the composer was displeased with.[158] He also apparently behaved incorrectly as trustee, causing Sorabji considerable monetary losses, which led to his removal from the Trust and the end of their friendship around 1942.[159] Occult themes rarely appeared in Sorabji's music and writings afterwards.[160]

Sorabji spoke favourably of the Parsis, though his experiences with them in India in the 1930s upset him. He embraced only a few aspects of Zoroastrianism before cutting his ties to various Parsi and Zoroastrian organisations over objections to their actions. However, he retained an interest in his Persian heritage, and insisted that his body should be cremated after his death (which is an alternative to using the Tower of Silence).[161]

Sorabji's attitude towards Christianity was mixed. In his early life, he denounced it for fuelling war and deemed it a hypocritical religion,[162] though he later voiced his admiration for the Catholic Church and attributed the most valuable parts of European civilisation to it. His interest in the Catholic Mass inspired his largest score, the Messa grande sinfonica.[163] Although he professed that he was not Catholic, he may have embraced some of the faith in private.[164]

Music

[edit]Early works

[edit]Although there has been speculation about earlier works, Sorabji's first known (albeit lost) composition is a 1914 piano transcription of Delius's orchestral piece In a Summer Garden.[165][166][167] His early works are predominantly piano sonatas, songs and piano concertos.[168] Of these, Piano Sonatas Nos. 1–3 (1919; 1920; 1922) are the most ambitious and developed.[169] They are characterised mainly by their use of the single-movement format and by their athematism.[170] The main criticism against them is that they lack stylistic consistency and organic form.[171][172] Sorabji developed a largely unfavourable view of his early works, described them as derivative and lacking in cohesion,[173] and even considered destroying many of their manuscripts late in his life.[174]

Middle-period works and symphonic style

[edit]

The Three Pastiches for Piano (1922) and Le jardin parfumé (1923) have often been seen as the beginning of Sorabji's compositional maturity.[175] Sorabji himself considered that it began with his Organ Symphony No. 1 (1924), his first work to make ample use of forms like the chorale prelude, the passacaglia and the fugue, which are descended from baroque music.[176] Their union with his earlier compositional ideas led to the emergence of what has been described as his "symphonic style", displayed in most of his seven symphonies for piano solo and three symphonies for organ.[176] The first piece to apply the architectural blueprint of this style is his Fourth Piano Sonata (1928–29), which is in three sections:

- An opening polythematic movement;

- An ornamental slow movement (labelled as a nocturne);

- A multi-sectional finale, which includes a fugue.[176]

Sorabji's symphonic first movements are related in their organisation to his Second and Third Piano Sonatas and the closing movement of his First Organ Symphony.[177] They have been described as being based superficially on either the fugue or the sonata-allegro form,[178][179] but they differ from the normal application of those forms: the exposition and development of themes are not guided by conventional tonal principles, but by how the themes, as the musicologist Simon John Abrahams says, "battle with each other for domination of the texture".[180] These movements can last over 90 minutes,[181] and their thematic nature varies considerably: while the opening movement of his Fourth Piano Sonata introduces seven themes, his Second Piano Symphony's has sixty-nine.[182] There is still a "dominant theme" or "motto" in these polythematic movements that is given primary significance and permeates the rest of the composition.[183]

The nocturnes are generally considered to be among Sorabji's most accessible works,[184] and they are also some of his most highly regarded; they have been described by Habermann as "the most successful and beautiful of [his] compositions",[184] and by the pianist Fredrik Ullén as "perhaps ... his most personal and original contribution as a composer".[185] Sorabji's descriptions of his Symphony No. 2, Jāmī, give an insight into their organisation.[186] He compared the piece to his nocturne Gulistān[187] and wrote of the symphony's "self-cohesive texture relying upon its own inner consistency and cohesiveness without relation to thematic or other matters".[188] Melodic material is treated loosely in such works;[189] instead of themes, ornamentation and textural patterns assume a preeminent position.[190][191] The nocturnes explore free, impressionist harmonies and are usually to be played at subdued dynamic levels, though some of the later ones contain explosive passagework.[192][193] They can be stand-alone works, such as Villa Tasca, or parts of larger pieces, like "Anāhata Cakra", the fourth movement of his Tāntrik Symphony for Piano Alone.[194][195] Sections titled "aria" and "punta d'organo" (the latter of which have been likened to "Le gibet" from Maurice Ravel's Gaspard de la nuit[196]) are included in this genre.[197][198]

Sorabji's fugues usually follow traditional methods of development and are the most atonal and least polyrhythmic of his works.[199][200] After an exposition introduces a subject and one to four countersubjects, the thematic material undergoes development.[n 13] It is followed by a stretto that leads to a section featuring augmentation and a thickening of lines into chords. If a fugue has multiple themes,[n 14] this pattern is repeated for each subject and material from all expositions is combined near the end.[203][n 15] Sorabji's fugal writing has at times been treated with suspicion or criticised. The subjects can lack the frequent changes of direction present in most melodic writing, and some of the fugues are among the longest ever penned, one being the two-hour "Fuga triplex" that closes the Second Symphony for Organ.[199][205][206]

This structural layout was employed and refined in most of Sorabji's piano and organ symphonies.[n 16] In some cases, a variation set takes the place of the slow movement.[183] Starting with the Second Symphony for Piano (1954), fugues are positioned either midway through the work or right before a closing slow movement.[207] Interludes and moto perpetuo-type sections link larger movements together and make appearances in Sorabji's later fugues,[208][209] like in the Sixth Symphony for Piano (1975–76), whose "Quasi fuga" alternates fugal and non-fugal sections.[210]

Other important forms in Sorabji's output are the toccata and the autonomous variation set.[211] The latter, along with his non-orchestral symphonies, are his most ambitious works and have been praised for the imagination exhibited in them.[212][213] Sequentia cyclica super "Dies irae" ex Missa pro defunctis (1948–49), a set of 27 variations on the original Dies irae plainchant, is considered by some to be his greatest work.[214] His four multi-movement toccatas are generally more modest in scope and take the structure of Busoni's work of the same name as their starting point.[215]

Late works

[edit]

In 1953, Sorabji expressed uninterest in continuing to compose when he described Sequentia cyclica (1948–49) as "the climax and crown of his work for the piano and, in all probability, the last he will write".[216][n 17] His rate of composition slowed down in the early 1960s,[91] and later that decade, Sorabji vowed to cease composing, which he eventually did in 1968.[107]

Hinton played a crucial role in Sorabji's return to composition.[217] Sorabji's next two pieces, Benedizione di San Francesco d'Assisi and Symphonia brevis for Piano, were written in 1973, the year after the two first met, and marked the beginning of what has been identified as his "late style",[218] one characterised by thinner textures and greater use of extended harmonies.[219][220] Roberge writes that Sorabji, upon completing the first movement of Symphonia brevis, "felt that it broke new ground for him and was his most mature work, one in which he was doing things he had never done before".[221] Sorabji said his late works were designed "as a seamless coat ... from which the threads cannot be disassociated" without compromising the coherence of the music.[222] During his late period and several years before his creative hiatus, he also produced sets of "aphoristic fragments", musical utterances that can last just a few seconds.[223]

Inspiration and influences

[edit]Sorabji's early influences include Cyril Scott, Ravel, Leo Ornstein and particularly Alexander Scriabin.[224] He later became more critical of Scriabin and, after meeting Busoni in 1919, was influenced primarily by the latter in both his music and writings.[225][226][227][n 18] His later work was also significantly influenced by the virtuoso writing of Charles-Valentin Alkan and Leopold Godowsky, Max Reger's use of counterpoint, and the impressionist harmonies of Claude Debussy and Karol Szymanowski.[231][232][233] Allusions to various composers appear in Sorabji's works, including his Sixth Symphony for Piano and Sequentia cyclica, which contain sections titled "Quasi Alkan" and "Quasi Debussy" respectively.[194]

Eastern culture partially influenced Sorabji. According to Habermann, it manifests itself in the following ways: highly supple and irregular rhythmic patterns, abundant ornamentation, an improvisatory and timeless feel, frequent polyrhythmic writing and the vast dimensions of some of his compositions.[234] Sorabji wrote in 1960 that he almost never sought to blend Eastern and Western music, and although he had positive things to say about Indian music in the 1920s, he later criticised what he saw as limitations inherent in it and the raga, including a lack of thematic development, which was sidelined in favour of repetition.[235] A major source of inspiration were his readings of Persian literature, especially for his nocturnes,[236] which have been described by Sorabji and others as evoking tropical heat, a hothouse or a rainforest.[237]

Various religious and occult references appear in Sorabji's music,[238] including allusions to the tarot, a setting of a Catholic benediction[239] and sections named after the seven deadly sins.[240] Sorabji rarely intended for his works to be programmatic; although pieces like "Quaere reliqua hujus materiei inter secretiora" and St. Bertrand de Comminges: "He was laughing in the tower" (both inspired by ghost stories by M. R. James)[241] have been described as such,[194] he repeatedly heaped scorn on attempts to represent stories or ideologies in music.[242][243][n 19]

Sorabji's interest in numerology can be seen in his allotting of a number to the length of his scores, the amount of variations a piece contains or the number of bars in a work.[245] Recent scholarly writings on Sorabji's music have suggested an interest in the golden section as a means of formal division.[246][247] Squares, repdigits and other numbers with special symbolism are common.[248] Page numbers may be used twice or absent to achieve the desired result;[60] for example, the last page of Sorabji's Piano Sonata No. 5 is numbered 343a, although the score has 336 pages.[158] This type of alteration is also seen in his numbering of variations.[249]

Sorabji, who claimed to be of Spanish-Sicilian ancestry, composed pieces that reflect an enthusiasm for Southern European cultures, such as Fantasia ispanica, Rosario d'arabeschi and Passeggiata veneziana. These are works of a Mediterranean character and are inspired by Busoni's Elegy No. 2, "All'Italia! in modo napolitano", and the Spanish music of Isaac Albéniz, Debussy, Enrique Granados and Franz Liszt. They are considered to be among his outwardly more virtuosic and musically less ambitious works.[250][251] French culture and art also appealed to Sorabji, and he set French texts to music.[252] Around 60 per cent of his known works have titles in Latin, Italian and other foreign languages.[253]

Harmony, counterpoint and form

[edit]Sorabji's counterpoint stems from Busoni and Reger, as did his reliance on theme-oriented baroque forms.[254][255] His use of these often contrasts with the more rhapsodic, improvisatory writing of his fantasias and nocturnes,[256] which, because of their non-thematic nature, have been called "static".[191] Abrahams describes Sorabji's approach as built on "self-organising" (baroque) and athematic forms that can be expanded as needed, as their ebb and flow is not dictated by themes.[191] While Sorabji wrote pieces of standard or even minute dimensions,[6][257] his largest works (for which he is perhaps best known)[114] call for skills and stamina beyond the reach of most performers;[258] examples include his Piano Sonata No. 5 (Opus archimagicum), Sequentia cyclica and the Symphonic Variations for Piano, which last about six, eight and nine hours respectively.[259][260][261][n 20] Roberge estimates that Sorabji's extant musical output, which he describes as "[perhaps] the most extensive of any twentieth-century composer",[263] may occupy up to 160 hours in performance.[264]

Sorabji's harmonic language often combines tonal and atonal elements, frequently uses triadic harmonies and bitonal combinations, and it does not avoid tonal references.[192][265] It also reflects his fondness for tritone and semitone relationships.[266] Despite the use of harmonies traditionally considered harsh, it has been remarked that his writing rarely contains the tension that is associated with very dissonant music.[267] Sorabji achieved this in part by using widely spaced chords rooted in triadic harmonies and pedal points in the low registers, which act as sound cushions and soften dissonances in the upper voices.[192][268] In bitonal passages, melodies may be consonant within a harmonic area, but not with those from the other one.[269] Sorabji uses non-functional harmony, in which no key or bitonal relationship is allowed to become established. This lends flexibility to his harmonic language and helps justify the superimposition of semitonally opposed harmonies.[270]

Creative process and notation

[edit]Because of Sorabji's sense of privacy, little is known about his compositional process. According to early accounts by Warlock, he composed off the cuff and did not revise his work. This claim is generally regarded as dubious and contradicts statements made by Sorabji himself (as well as some of his musical manuscripts). In the 1950s, Sorabji stated that he would conceive the general outline of a work in advance and long before the thematic material.[271] A few sketches survive; crossed-out passages are mostly found in his early works.[272] Some have claimed that Sorabji used yoga to gather "creative energies", when in fact it helped him regulate his thoughts and achieve self-discipline.[273] He found composition enervating and often completed works with headaches and experiencing sleepless nights afterwards.[112]

The unusual features of Sorabji's music and the "ban" resulted in idiosyncrasies in his notation: a shortage of interpretative directions, the relative absence of time signatures (except in his chamber and orchestral works) and the non-systematic use of bar lines.[274] He wrote extremely quickly, and there are many ambiguities in his musical autographs,[275][276] which has prompted comparisons with his other characteristics.[277] Hinton suggested a link between them and Sorabji's speech,[278] and said that "[Sorabji] invariably spoke at a speed almost too great for intelligibility",[7] while Stevenson remarked, "One sentence could embrace two or three languages."[278] Sorabji's handwriting, particularly after he began to suffer from rheumatism, can be difficult to decipher.[279] After complaining about errors in one of his open letters, the editor of the journal responded, "If Mr. Sorabji will in future send his letters in typescript instead of barely decipherable handwriting, we will promise a freedom from misprints".[280][281] In later life, similar issues came to affect his typewriting.[282]

Pianism and keyboard music

[edit]As a performer

[edit]Sorabji's pianistic abilities have been the subject of much contention. After his early lessons, he appeared to have been self-taught.[283] In the 1920s and 1930s, when he was performing his works in public, their alleged unplayability and his piano technique generated considerable controversy. At the same time, his closest friends and a few other people hailed him as a first-class performer. Roberge says that he was "far from a polished virtuoso in the usual sense",[264] a view shared by other writers.[284]

Sorabji was a reluctant performer and struggled with the pressure of playing in public.[285] On various occasions, he stated that he was not a pianist,[7] and he always prioritised composition; from 1939, he no longer practised the piano often.[286] Contemporary reviews noted Sorabji's tendency to rush the music and his lack of patience with quiet passages,[287] and the private recordings that he made in the 1960s contain substantial deviations from his scores, attributed in part to his impatience and uninterest in playing clearly and accurately.[288][289] Writers have thus argued that early reactions to his music were significantly coloured by flaws in his performances.[189][290]

As a composer

[edit]

Many of Sorabji's works are written for the piano or have an important piano part.[291] His writing for the instrument was influenced by composers such as Liszt and Busoni, and he has been called a composer-pianist in their tradition.[292][293] Godowsky's polyphony, polyrhythms and polydynamics were particularly influential and led to the regular use of the sostenuto pedal and systems of three or more staves in Sorabji's keyboard parts; his largest such system appears on page 124 of his Third Organ Symphony and consists of 11 staves.[231][294][295] In some works, Sorabji writes for the extra keys available on the Imperial Bösendorfer. While its extended keyboard includes only additional low notes, at times he called for extra notes at its upper end.[296]

Sorabji's piano writing has been praised by some for its variety and understanding of the piano's sonorities.[185][297][298][n 21] His approach to the piano was non-percussive,[300] and he emphasised that his music is conceived vocally. He once described Opus clavicembalisticum as "a colossal song", and the pianist Geoffrey Douglas Madge compared Sorabji's playing to bel canto singing.[301] Sorabji once said, "If a composer can't sing, a composer can't compose."[302]

Some of Sorabji's piano pieces strive to emulate the sounds of other instruments, as seen in score markings such as "quasi organo pieno" (like a full organ), "pizzicato" and "quasi tuba con sordino" (like a tuba with mute).[303] In this respect, Alkan was a key source of inspiration: Sorabji was influenced by his Symphony for Solo Piano and the Concerto pour piano seul, and he admired Alkan's "orchestral" writing for the instrument.[180][304]

Organ music

[edit]Besides the piano, the other keyboard instrument to occupy a prominent position in Sorabji's output is the organ.[305] Sorabji's largest orchestral works have organ parts,[197] but his most important contribution to the instrument's repertoire are his three organ symphonies (1924; 1929–32; 1949–53), all of which are large-scale tripartite works that consist of multiple subsections and last up to nine hours.[306] Organ Symphony No. 1 was regarded by Sorabji as his first mature work and he numbered the Third Organ Symphony among his finest achievements.[176][307] He considered even the best orchestras of the day to be inferior to the modern organ and wrote of the "tonal splendour, grandeur and magnificence" of the instruments in Liverpool Cathedral and the Royal Albert Hall.[308][n 22] Organists were described by him as being more cultured and having sounder musical judgement than most musicians.[309]

Creative transcription

[edit]Transcription was a creative endeavour for Sorabji, as it had been for many of the composer-pianists who inspired him: Sorabji echoed Busoni's view that composition is the transcription of an abstract idea, as is performance.[310][311] For Sorabji, transcription enabled older material to undergo transformation to create an entirely new work (which he did in his pastiches), and he saw the practice as a way to enrich and uncover the ideas concealed in a piece.[312] His transcriptions include an adaptation of Bach's Chromatic Fantasia, in the preface to which he denounced those who perform Bach on the piano without "any substitution in pianistic terms".[313] Sorabji praised performers like Egon Petri and Wanda Landowska for taking liberties in performance and for their perceived ability to understand a composer's intentions, including his own.[314]

Writings

[edit]As a writer, Sorabji is best known for his music criticism. He contributed to publications that dealt with music in England, including The New Age, The New English Weekly, The Musical Times and Musical Opinion.[315] His writings also cover non-musical issues: he criticised British rule in India and supported birth control and legalised abortion.[316] As a homosexual in a time when male same-sex acts were illegal in England (and remained so until 1967), he wrote about the biological and social realities that homosexuals faced for much of his lifetime.[317][318] He first published an article on the subject in 1921, in response to a legislative change that would penalise "gross indecency" between women. The article referenced research showing that homosexuality was inborn and could not be cured by imprisonment. It further called for the law to catch up with the latest medical findings, and advocated for decriminalising homosexual behaviour. Sorabji's later writings on sexual topics include contributions to The Occult Review and the Catholic Herald, and in 1958, he joined the Homosexual Law Reform Society.[319]

Books and music criticism

[edit]

Sorabji first expressed interest in becoming a music critic in 1914, and he started contributing criticism to The New Age in 1924 after the magazine had published some of his letters to the editor. By 1930, Sorabji became disillusioned with concert life and developed a growing interest in gramophone recordings, believing that he would eventually lose all reason to attend concerts. In 1945, he stopped providing regular reviews and only occasionally submitted his writings to correspondence columns in journals.[320] While his earlier writings reflect a contempt for the music world in general—from its businessmen to its performers[321]—his later reviews tend to be more detailed and less caustic.[322]

Although in his youth Sorabji was attracted to the progressive currents of 1910s' European art music, his musical tastes were essentially conservative.[323] He had a particular affinity for late-Romantic and Impressionist composers, such as Debussy, Medtner and Szymanowski,[324] and he admired composers of large-scale, contrapuntally elaborate works, including Bach, Gustav Mahler, Anton Bruckner and Reger. He also had much respect for composer-pianists like Liszt, Alkan and Busoni.[325] Sorabji's main bêtes noires were Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg (from the late 1920s onwards), Paul Hindemith and, in general, composers who emphasised percussive rhythm.[326] He rejected serialism and twelve-tone composition, as he considered both to be based on artificial precepts,[327] denounced Schoenberg's vocal writing and use of Sprechgesang,[328] and even criticised his later tonal works and transcriptions.[329] He loathed the rhythmic character of Stravinsky's music and what he perceived as its brutality and lack of melodic qualities.[330] He viewed Stravinsky's neoclassicism as a sign of a lack of imagination. Sorabji was also dismissive of the symmetry and architectural approaches used by Mozart and Brahms,[331] and believed that the Classical style restricted musical material by forcing it into a "ready-made mould".[332] Gabriel Fauré and Dmitri Shostakovich are among the composers whom Sorabji initially condemned but later admired.[333]

Sorabji's best-known writings are the books Around Music (1932; reissued 1979) and Mi contra fa: The Immoralisings of a Machiavellian Musician (1947; reissued 1986); both include revised versions of some of his essays and received mostly positive reviews, though Sorabji considered the latter book much better.[315][334] Readers commended his courage, expertise and intellectual incisiveness, but some felt that his verbose style and use of invectives and vitriol detracted from the solid foundation underlying the writings.[335] These remarks echo general criticisms of his prose, which has been called turgid and in which intelligibility is compromised by very long sentences and missing commas.[336] In recent times, his writings have been highly divisive, being viewed by some as profoundly perceptive and enlightening, and by others as misguided,[337] but the literature on them remains limited. Abrahams mentions that Sorabji's music criticism was restricted largely to one readership and says that much of it, including Around Music and Mi contra fa, has yet to receive a major critique.[338]

Roberge writes that Sorabji "could sing the praises of some modern British personalities without end, especially when he knew them, or he could tear their music to pieces with very harsh and thoughtless comments that would nowadays lay him open to ridicule";[339] he adds that "his biting comments also often brought him to the edge of libel".[339] Sorabji championed a number of composers and his advocacy helped many of them move closer to the mainstream at a time when they were largely unknown or misunderstood.[340] In some cases, he was recognised for promoting their music: he became one of the honorary vice-presidents of the Alkan Society in 1979, and in 1982, the Polish government awarded him a medal for championing Szymanowski's work.[341]

Legacy

[edit]Reception

[edit]Sorabji's music and personality have inspired both praise and condemnation, the latter of which has been often attributed to the length of some of his works.[342][343] Hugh MacDiarmid ranked him as one of the four greatest minds Great Britain had produced in his lifetime, eclipsed only by T. S. Eliot,[344] and the composer and conductor Mervyn Vicars put Sorabji next to Richard Wagner, who he believed "had one of the finest brains since Da Vinci".[345] By contrast, several major books on music history, including Richard Taruskin's 2005 Oxford History of Western Music, do not mention Sorabji, and he has never received official recognition from his country of birth.[346] A 1994 review of Le jardin parfumé (1923) suggested that "the unsympathetic might say that besides not belonging in our time it equally belongs in no other place",[347] and in 1937, one critic wrote that "one could listen to many more performances without really understanding the unique complexity of Sorabji's mind and music".[348]

In recent times, this divided reception has persisted to an extent. While some compare Sorabji to composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Chopin and Messiaen,[189][349][350][351] others dismiss him altogether.[342][343][352][353] The pianist and composer Jonathan Powell writes of Sorabji's "unusual ability to combine the disparate and create surprising coherence".[354] Abrahams finds that Sorabji's musical production exhibits enormous "variety and imagination" and calls him "one of the few composers of the time to be able to develop a unique personal style and employ it freely at any scale he chose".[355] The organist Kevin Bowyer counts Sorabji's organ works, together with those of Messiaen, among the "Twentieth-Century Works of Genius".[356] Others have expressed more negative sentiments. The music critic Andrew Clements calls Sorabji "just another 20th-century English eccentric ... whose talent never matched [his] musical ambition".[357] The pianist John Bell Young described Sorabji's music as "glib repertoire" for "glib" performers.[358] The musicologist and critic Max Harrison, in his review of Rapoport's book Sorabji: A Critical Celebration, wrote unfavourably about Sorabji's compositions, piano playing, writings and personal conduct and implied that "nobody cared except a few close friends".[359] Another assessment was offered by the music critic Peter J. Rabinowitz, who, reviewing the 2015 reissue of Habermann's early Sorabji recordings, wrote that they "may provide a clue about why—even with the advocacy of some of the most ferociously talented pianists of the age—Sorabji's music has remained arcane". While saying that "it's hard not to be captivated, even hypnotized, by the sheer luxury of [his] nocturnes" and praising the "angular, dramatic, electrically crackling gestures" of some of his works, he claims that their tendency to "ostentatiously avoid the traditional Western rhetoric ... that marks out beginning, middle, and end or that sets up strong patterns of expectation and resolution" makes them hard to approach.[360]

Roberge says that Sorabji "failed to realize ... that negative criticism is part of the game, and that people who can be sympathetic to one's music do exist, though they may sometimes be hard to find",[361] and Sorabji's lack of interaction with the music world has been criticised even by his admirers.[359][362][363] In September 1988, following lengthy conversations with the composer, Hinton founded The Sorabji Archive to disseminate knowledge of Sorabji's legacy.[364][365] His musical autographs are located in various places across the world, with the largest collection of them residing in the Paul Sacher Stiftung (Basel, Switzerland).[366][n 23] While much of his music remained in manuscript form until the early 2000s, interest in it has grown since then, with his piano works being the best represented by recordings and modern editions.[368][369] Landmark events in the discovery of Sorabji's music include performances of Opus clavicembalisticum by Madge and John Ogdon, and Powell's recording of Sequentia cyclica.[364][370] First editions of many of Sorabji's piano works have been made by Powell and the pianist Alexander Abercrombie, among others, and the three organ symphonies have been edited by Bowyer.[371]

Innovation

[edit]Sorabji has been described as a conservative composer who developed an idiosyncratic style fusing diverse influences.[372][373][374] However, the perception of and responses to his music have evolved over the years. His early, often modernist works were greeted largely with incomprehension:[375] a 1922 review stated, "compared to Mr. Sorabji, Arnold Schönberg must be a tame reactionary",[376] and the composer Louis Saguer, speaking at Darmstadt in 1949, mentioned Sorabji as a member of the musical avant-garde that few will have the means to understand.[377] Abrahams writes that Sorabji "had begun his compositional career at the forefront of compositional thought and ended it seeming decidedly old-fashioned", yet adds that "even now Sorabji's 'old-fashioned' outlook sometimes remains somewhat cryptic".[378]

Various parallels have been identified between Sorabji and later composers. Ullén suggests that Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Studies (1940–1944) can be seen as presaging the piano music of Ligeti, Michael Finnissy and Brian Ferneyhough, although he cautions against overstating this.[372] Roberge compares the opening of Sorabji's orchestral piece Chaleur—Poème (1916–17) to the micropolyphonic texture of Ligeti's Atmosphères (1961) and Powell has noted the use of metric modulation in Sequentia cyclica (1948–49), which was composed around the same time as (and independently from) Elliott Carter's 1948 Cello Sonata, the first work in which Carter employed the technique.[379][380][n 24] The mixing of chords with different root notes and the use of nested tuplets, both present throughout Sorabji's works, have been described as anticipating Messiaen's music and Stockhausen's Klavierstücke (1952–2004) respectively by several decades.[384] Sorabji's fusion of tonality and atonality into a new approach to relationships between harmonies, too, has been called an important innovation.[385]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources spell this name as Shapurjee Sorabjee.[2]

- ^ Sorabji was born Leon Dudley Sorabji and disliked his original "beastly English-sounding names".[18][19] He experimented with various forms of his name, settling for Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji only in 1934.[20] In a 1975 letter, he offered the following information on its pronunciation: "KYKHOSRU with accent of FIRST syllable; Y long, as in EYE. Shapurji: SHAPOORji with accent on FIRST. Sorabji should really also have accent on FIRST syllable but English-speaking persons seem to have an innate tendency to lean upon the SECOND, so I've usually left it at that, but it SHOULD be on the FIRST. The vowels all with CONTINENTAL or, say, ITALIAN values."[21]

- ^ Sorabji identified with Mediterranean cultures and his Persian heritage, and he visited Italy at least eight times, occasionally for extended periods.[23]

- ^ The recital featuring the Fourth Sonata was part of a concert series titled "Recitals of National Music" and was not sponsored by Chisholm's Society.[8]

- ^ Sorabji's friend Edward Clarke Ashworth, who attended the concert, described Tobin's performance as unimaginative and lacking in understanding and said the fugues in particular had been played too slowly.[40]

- ^ The court decision also said that Sorabji's father had, in the 1880s, married an Indian woman, whose date of death is unknown.[54]

- ^ The name derives from the Eye of Horus, which was engraved on a metal plate near the entrance.[63]

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Sorabji suffered from frail health throughout his life: he broke his leg as a child; experienced recurring attacks of malaria, which is attributed to his two trips to India; was diagnosed with sciatica in 1976, which hampered his ability to walk and sometimes left him housebound. He was crippled with arthritis near the end of his life.[87] He preferred his physiotherapist over doctors and had an interest in alternative medicine and spiritual healing.[88] He experimented with herbal remedies and over-the-counter products, and practised weekly one-day fasts and yearly one-week fasts for many years.[89]

- ^ Sorabji's 1963 will dictated that his manuscripts should go to Gentieu's Society or, should that prove impossible, to the Library of Congress.[96] In his will of May 1969, he changed this to Holliday.[97]

- ^ Later, on 19 September 1988 (less than a month before his death), Sorabji registered for the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society and became the oldest composer to have ever applied to the list.[102]

- ^ Sorabji's ring was determined by experts from Sotheby's and the Victoria and Albert Museum to have been made in 1914 by London-based firm Paton & Co.[118]

- ^ Particularly in the earlier fugues, not only the subject, but occasionally also the countersubjects are developed.[201]

- ^ Sorabji's fugues can contain up to six themes.[202]

- ^ The number of voices is sometimes changed with the introduction of a new subject.[204]

- ^ Only Sorabji's Piano Symphonies Nos. 3 and 5 deviate from this model.[183]

- ^ Sorabji wrote this in the third person, as it is part of his 1953 essay Animadversions. Essay about His Works Published on the Occasion of the Microfilming of Some of His Manuscripts.

- ^ Sorabji repeatedly changed his mind about Scriabin's music.[225] For instance, in 1934, he stated that it lacks any kind of motivic coherence,[228] but he later came to admire and be inspired by it again.[229][230]

- ^ The only piece for which Sorabji wrote a programmatic preface is Chaleur—Poème (1916–17), one of his earliest works.[244]

- ^ Sorabji's piano symphonies and four multi-movement piano toccatas all last over 60 minutes and most of them occupy two or more hours, as do the complete 100 Transcendental Studies, Opus clavicembalisticum, his Fourth Piano Sonata and several other works.[262]

- ^ Sorabji's orchestration, in turn, has been sharply criticised.[205][285][299]

- ^ A separate page with Sorabji's comment is part of the microfilm of Organ Symphony No. 3 made in the 1950s.[208]

- ^ Most of the Sorabji manuscripts in the Paul Sacher Stiftung's possession were acquired in 1994.[367]

- ^ Though most sources date Sequentia cyclica to 1948–49, Roberge, citing a letter by Sorabji from January 1948, suggests work on it may have begun already in 1944.[381] Powell identifies the use of metric modulation in variation 11, which spans pages 130–132 of the 335-page manuscript.[382][383]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Roberge, Marc-André (3 July 2020). "Biographical Notes". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b Owen, p. 40

- ^ Owen, pp. 40–41

- ^ Owen, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b Hinton, Alistair (2005). "Sorabji's Songs (1/4)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Rapoport, p. 18

- ^ a b c Rapoport, p. 33

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 205

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 49

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 308

- ^ Owen, p. 21

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 50–51

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 53

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 62–63

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 54–55

- ^ McMenamin, pp. 43–51

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 67–68

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 67

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Clive Spencer-Bentley, 6 October 1980, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 67

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (29 June 2020). "Forms of Sorabji's Name". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Harold Rutland, 18 August 1975, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 67

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 277

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 69, 275–276

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 252–254

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 86–87

- ^ Owen, pp. 279–280

- ^ a b Roberge, Marc-André (29 June 2020). "Dimensions and Colours of the Published Editions". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Owen, pp. 21–24

- ^ Abrahams, p. 15

- ^ Frederick Delius. Letter to Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, 23 April 1930, reproduced in Rapoport, p. 280

- ^ Rapoport, p. 360

- ^ Grew, p. 85

- ^ Rapoport, p. 240

- ^ a b c "Concerts – Listing". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 168

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Erik Chisholm, 25 December 1929, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 206

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 169

- ^ Purser, pp. 214–221

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 205–206

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 228

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 229

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 229, 233

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 232

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 230–231

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 232–233, 378–379

- ^ Owen, p. 25

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 147–156

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 2, 240

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 5–6, 190

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 37

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 203

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 111

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 198

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 38

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 201–202

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 202

- ^ Owen, p. 43

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 338

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Erik Chisholm, 6 September 1936, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 120

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 120

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 55

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 280–281

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 294

- ^ Rapoport, p. 223

- ^ a b c Roberge (2020), p. 291

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 273, 292

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 231–232

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Anthony Burton-Page, 3 September 1979, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 291

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Frank Holliday, 1 December 1954, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 291

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 204

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 274, 308

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 294–295, 308–309

- ^ Owen, p. 26

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 317–318

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 252

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 253

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 231

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 253–254

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 255

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 256–257

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. xxv, 257–258

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 47, 252

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 258

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 304

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 311–312

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 303

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 297, 338

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 338–339

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 337, 339

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 333

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), pp. 339–340

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 19, 22–23

- ^ Rapoport, p. 30

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 256

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 257, 368

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 305

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 255–256

- ^ Rapoport, p. 37

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 369

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 39, 41

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 381

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 382

- ^ Rapoport, p. 41

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 401

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 391

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 407

- ^ a b Owen, p. 295

- ^ Owen, p. 57

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 204, 246

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 72

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 408

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 298

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. xxii

- ^ a b Owen, p. 16

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. xxv–xxvi

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (2 July 2020). "Manuscripts with Peculiarities". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. xxv

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 44

- ^ Owen, p. 102

- ^ Owen, p. 315

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 70–72

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. xxi

- ^ Slonimsky, p. 152

- ^ Owen, pp. 34–35

- ^ Owen, pp. 311–312

- ^ Owen, p. 3

- ^ Owen, pp. 314–317

- ^ Owen, p. 317

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 149

- ^ Owen, pp. 46–48

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 138–139

- ^ Owen, pp. 47–48

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 59

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 170–171

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 152, 172

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 295

- ^ Owen, pp. 46–47

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Kenneth Derus, 30 December 1977, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 295

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 298, 409

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 45

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Kenneth Derus, 30 December 1977, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 152

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 152–153

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 47

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 251, 322, 368

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 322

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 251

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 280

- ^ Owen, p. 51

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Robert (Wilfred Levick) Simpson, 29 June 1948, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 296

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 296, 323

- ^ Sorabji (1930b), pp. 42–43, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 270

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 70, 338

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 117–119

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Peter Warlock, 24 June 1922, reproduced in Rapoport, p. 247

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Peter Warlock, 19 June 1922, reproduced in Rapoport, p. 245

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 118

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 221

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 223

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 222

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 118–119

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 68–69, 408

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 54, 330

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 276

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 331

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 35–36

- ^ Owen, p. 278

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 109, 214

- ^ Abrahams, p. 160

- ^ Abrahams, p. 227

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 162, 176

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 176, 207

- ^ Rapoport, p. 355

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 227–228

- ^ Abrahams, p. 35

- ^ Powell (2003a), p. [3]

- ^ a b c d Abrahams, p. 163

- ^ Abrahams, Simon John (2003). "Sorabji's Orchard: The Path to Opus Clavicembalisticum and Beyond (1/3)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Abrahams, p. 178

- ^ Owen, p. 285

- ^ a b Abrahams, p. 177

- ^ Abrahams, Simon John (2003). "Sorabji's Orchard: The Path to Opus Clavicembalisticum and Beyond (3/3)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 311

- ^ a b c Abrahams, p. 165

- ^ a b Rapoport, p. 359

- ^ a b Ullén (2010), p. 5

- ^ Abrahams, p. 181

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Frank Holliday, 8 November 1942, reproduced in Rapoport, p. 319

- ^ Sorabji (1953), p. 18, reproduced in Abrahams, p. 181

- ^ a b c Rapoport, p. 389

- ^ Rapoport, p. 340

- ^ a b c Abrahams, p. 225

- ^ a b c Roberge (2020), p. 28

- ^ Abrahams, p. 182

- ^ a b c Roberge, Marc-André (2 July 2020). "Titles of Works Grouped by Categories". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 241

- ^ Abrahams, p. 194

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 23

- ^ Abrahams, p. 183

- ^ a b Rapoport, p. 348

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 188–189

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 187–188

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (7 July 2020). "Variations, Passacaglias, and Fugues". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 185–186

- ^ Abrahams, p. 186

- ^ a b Owen, p. 221

- ^ Pemble, John (9 February 2017). "Eight-Hour Work Introduces A New Organ In Iowa City". Iowa Public Radio. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Abrahams, p. 164

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 306

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 165, 183, 186–187

- ^ Rapoport, p. 170

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 168–169

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 168, 227

- ^ Rapoport, p. 350

- ^ Roberge (1996), p. 130

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 169–171

- ^ Sorabji (1953), p. 9, reproduced in Abrahams, p. 154

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 340, 368

- ^ Inglis, p. 49

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 228–229

- ^ Owen, p. 283

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 372

- ^ Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji. Letter to Norman Gentieu, 28 November 1981, reproduced in Roberge (2020), p. 391

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 238, 388

- ^ Rapoport, p. 199

- ^ a b Owen, p. 303

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 199, 267

- ^ Abrahams, p. 150

- ^ Sorabji (1934), pp. 141–142

- ^ Rapoport, p. 200

- ^ Abrahams, p. 217

- ^ a b Roberge (1991), p. 79

- ^ Rubin, Justin Henry (2003). "Thematic Metamorphosis and Perception in the Symphony [No. 1] for Organ of Kaikhosru Sorabji (2/7)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 176–177, 223

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 340, 366

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 199–200

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 69

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 23, 90

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 62–65

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (2 July 2020). "Musical and Literary Sources". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 154

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 259

- ^ Owen, p. 289

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 56–57

- ^ Rapoport, p. 180

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 89, 120

- ^ Huisman, p. 3

- ^ Mead, p. 218

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 120–121

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 121

- ^ Abrahams, p. 171

- ^ Rapoport, p. 358

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 274

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (2 July 2020). "Titles of Works Grouped by Language". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Rapoport, p. 346

- ^ Abrahams, p. 205

- ^ Abrahams, p. 173

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 238

- ^ Owen, p. 294

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (7 July 2020). "Performed Works and Durations". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "KSS58 Piano Sonata No. 5 Opus Archimagicum". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "KSS59 Symphonic Variations". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 439–461

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 1

- ^ a b Roberge (2020), p. 12

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 335, 340, 388

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 76, 212

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 340, 424

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 194–195

- ^ Abrahams, p. 206

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 203–210

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 2

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 2, 90

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 64–66

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 15

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 53–67

- ^ Owen, p. 306

- ^ Abrahams, p. 241

- ^ a b Stevenson, p. 35

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 376

- ^ Editorial postscript to Sorabji (1930a), p. 739

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 376–377

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 377

- ^ Owen, p. 280

- ^ Abrahams, p. 45

- ^ a b Rapoport, p. 83

- ^ Rapoport, p. 80

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 206

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 81–82

- ^ Abrahams, p. 51

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 37–53

- ^ Roberge (1997), pp. 95–96

- ^ Roberge (1983), p. 20

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 340, 342

- ^ Roberge, Marc-André (3 July 2020). "Advanced Keyboard Writing". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Abrahams, p. 80

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 16–17

- ^ Abrahams, p. 223

- ^ Gray-Fisk, p. 232

- ^ Hinton, Alistair (n.d.). "Sorabji's piano concertos (2/2)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Rapoport, p. 362

- ^ Rapoport, pp. 392–393

- ^ Owen, p. 287

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 234–236

- ^ Powell (2006), pp. [5], [7]

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 211

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 12, 144, 213, 306

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 30, 306–307

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 305–306

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 211–212

- ^ Roberge (1991), p. 74

- ^ Abrahams, p. 233

- ^ Roberge (1991), p. 82

- ^ Roberge (2020), pp. 258–259

- ^ Abrahams, pp. 237–240

- ^ a b Rapoport, p. 257

- ^ Rapoport, p. 260

- ^ Roberge (2020), p. 152

- ^ Owen, p. 46