Kes (film)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

This article possibly contains original research. (May 2021) |

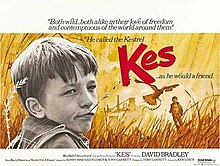

| Kes | |

|---|---|

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Loach |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines |

| Produced by | Tony Garnett |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Chris Menges |

| Edited by | Roy Watts |

| Music by | John Cameron |

Production companies | Woodfall Film Productions Kestrel Films |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English Yorkshire Dialect |

| Budget | £157,000[2] |

Kes (/kɛs/) is a 1969 British coming-of-age drama film directed by Ken Loach (credited as Kenneth Loach) and produced by Tony Garnett, based on the 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave, written by the Hoyland Nether–born author Barry Hines.[3] Kes follows the story of Billy, who comes from a dysfunctional working-class family and is a no-hoper at school, but discovers his own private means of fulfilment when he adopts a fledgling kestrel and proceeds to train it in the art of falconry.

The film has been much praised, especially for the performance of the teenage David Bradley, who had never acted before, in the lead role, and for Loach's compassionate treatment of his working-class subject; it remains a biting indictment of the British educational system of the time as well as of the limited career options then available to lower-class, unskilled workers in regional Britain. It was ranked seventh in the British Film Institute's Top Ten (British) Films.[4] This was Loach's second feature film for cinema release.

Plot

[edit]Fifteen-year-old Billy Casper, growing up in the late 1960s in a poor South Yorkshire community dominated by the local coal mining industry, has little hope in life. He is picked on, both at home by his physically and verbally abusive older half-brother, Jud (who works at the mine), and at school by his schoolmates and abusive teachers. Although he insists that his earlier petty criminal behaviour is behind him, he occasionally steals eggs and milk from milk floats. He has difficulty paying attention in school and is often provoked into tussles with classmates. Billy's father left the family some time ago, and his mother refers to him at one point, while somberly speaking to her friends about her children and their chances in life, as a "hopeless case". Billy is due to leave school soon, as an "Easter Leaver", without taking any public examinations (and therefore no qualifications); Jud states early in the film that he expects Billy will shortly be joining him at work in the mine, whereas Billy says that he does not know what job he will do, but also says nothing would make him work in the mine.

One day, Billy takes a kestrel from a nest on a farm. His interest in learning falconry prompts him to steal a book on the subject from a secondhand book shop, as he is underage and needs – but lies about the reasons he cannot obtain – adult authorisation for a borrower's card from the public library. As the relationship between Billy and "Kes", the kestrel, improves during the training, so does Billy's outlook and horizons. For the first time in the film, Billy receives praise, from his English teacher after delivering an impromptu talk about training Kes.

Jud leaves money and instructions for Billy to place a bet on two horses but after consulting a punter, who tells him the horses are unlikely to win, Billy spends the money on fish and chips and intends to purchase meat for his bird (instead the butcher gives him scrap meat free of charge). The horses win; outraged at losing a payout of more than £10, Jud takes revenge by killing Billy's kestrel. Grief-stricken, Billy retrieves the bird's broken body from the waste bin and shows it to Jud and his mother. After an argument, Billy buries the bird on the hillside overlooking the field where he had flown.

Cast

[edit]- Dai Bradley (credited as "David Bradley") as Billy Casper

- Freddie Fletcher as Jud

- Lynne Perrie as Mrs. Casper

- Colin Welland as Mr. Farthing

- Brian Glover as Mr. Sugden

- Bob Bowes as Mr. Gryce

- Steve Crossland as Billy's friend

- Bernard Atha as youth employment officer

- Joey Kaye as pub comedian

- Robert Naylor as MacDowell

- Joe Miller as Reg, mother's friend

- Bill Dean as fish and chip shop man

- Duggie Brown as milkman

- Trevor Hesketh as Mr. Crossley

- David Glover as Tibbutt

Background

[edit]The film (and the book upon which it was based, by Barry Hines) were semi-autobiographical, Hines having been a teacher in the school in which it was set, and wishing to critique the education system of the time. His younger brother Richard had found a new life after his student experiences at the local secondary modern school by training the original bird "Kes", the inspiration for the movie. Richard assisted the movie production by acting as the handler for the birds in the film. Both brothers grew up in the area shown in the film, and their father was a worker in the local coal mine, though he was a kind man in contrast to the absentee father in the film.[5] Both the film and the book provide a portrait of life in the mining areas of Yorkshire of the time; reportedly, the miners in the area were then the lowest-paid workers in a developed country.[6] Shortly before the film's release, the Yorkshire coalfield where the film was set was brought to a standstill for two weeks by an unofficial strike.

Production

[edit]Set in and around Barnsley, the film was one of the first of several collaborations between Ken Loach and Barry Hines that used authentic Yorkshire dialect. The extras were all hired from in and around Barnsley. The DVD version of the film has certain scenes dubbed over with fewer dialect terms than in the original. In a 2013 interview, director Ken Loach said that, upon its release, United Artists organised a screening of the film for some American executives and they said that they could understand Hungarian better than the dialect in the film.[7]

The production company was set up with the name "Kestrel Films". Ken Loach and Tony Garnett used this for some of their later collaborations such as Family Life and The Save the Children Fund Film.

Filming locations

[edit]The film was shot on location, including in St Helens School, Athersley South, and Edward Sheerien School (demolished in 2011); and in and around the streets of Hoyland and Hoyland Common in South Yorkshire. A number of the shooting locations are detailed in a "then and now" comparison page compiled by Adam Scovell in 2018.[8]

Textual themes

[edit]Much of the film's content has been discussed as a critique of the British education system of the time, known as the Tripartite System, which sorted children into different types of schools depending on their academic ability. The view of the creators is that such a system was harmful both to the children involved and to wider society. In his 2006 book, Life After Kes, Simon Golding commented that "Billy Casper, unlike the author [Golding], was a victim of the 11-plus, a government directive that turned out, for those who passed the exam, prospective white-collar workers, fresh from grammar schools, into jobs that were safe and well paid. The failures, housed in secondary modern schools, could only look forward to unskilled manual labour or the dangers of the coal face. Kes protests at this educational void that does not take into account individual skills, and suggests this is a consequence of capitalist society, which demands a steady supply of unskilled labour."[9] Golding also quoted director Ken Loach who stated that, "It [the film] should be dedicated to all the lads who had failed their 11-plus. There's a colossal waste of people and talent, often through schools where full potential is not brought out."[9]

In Ken Loach: The Politics of Film and Television, John Hill noted how the film's producers were against the bleak depiction of educational prospects for children in the film, writing, "Garnett [the film's producer] recalls how, in raising finance for the film, they encountered pressures to make the film's ending more positive, such as having Billy – with the help of his teacher – obtain a job at a zoo. As Garnett observes, however, this would have been to betray the film's point of view, which was concerned to raise questions about 'the system' rather than individuals."[10]

The film has also been noted for its themes around familial bonds during childhood and the effect their absence can have on children. Actor Andrew Garfield, who played Billy in a stage adaptation of Kes early in his career, commented that, "Billy needs to be loved by both his mother and brother. Like any child, he instinctively loves them both. He may resent his mother for not seeming to care about him, but he cannot help but love her. This causes Billy a lot of emotional pain when his mother rejects him. With Jud the rejection is even more blatant; he goes out of his way to hurt Billy, both physically and emotionally. Billy desires approval, comfort, support, guidance and attention from his family, but he receives nothing from them. A hug from his mum would make his day. I believe that love does exist within his family but expressing it is considered to be embarrassing and inappropriate. ... I think that Kes represents to Billy the ideal relationship that he finds so difficult to have with the people around him. Billy trusts, protects and is supported by Kes. He spends all of his time thinking of Kes and day dreaming about her. Billy looks up to Kes and feels privileged to be her friend. Kes has everything that Billy desires: freedom, pride, respect and independence."[11]

Release

[edit]Certification

[edit]The certificate given to the film has occasionally been reviewed by the British Board of Film Classification, as there is a small amount of swearing, including more than one instance of the word twat. It was originally classified by the then British Board of Film Censors as U for Universal (suitable for children), at a time when the only other certificates were A (more suitable for adult audiences) and X (for showing when no person under 16 years was present ... raised to 18 years in July 1970). Three years later, Stephen Murphy, the BBFC Secretary, wrote in a letter that it would have been given the new Advisory certificate under the system then in place.[12] Murphy also argued that the word "bugger" is a term of affection and not considered offensive in the area that the film was set. In 1987, the VHS release was given a PG certificate on the grounds of "the frequent use of mild language", and the film has remained PG since that time.[13]

Home media

[edit]A digitally restored version of the film was released on DVD and Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection in April 2011. The extras feature a new documentary featuring Loach, Menges, producer Tony Garnett, and actor David Bradley, a 1993 episode of The South Bank Show with Ken Loach, Cathy Come Home (1966), an early television feature by Loach, with an afterword by film writer Graham Fuller, and an alternative, internationally released soundtrack, with postsync dialogue.[14]

Reception

[edit]The film took several months to find a cinema release. It was eventually picked up by ABC Cinemas and had a successful run in some cinemas in north England which went very well and led to the film being expanded throughout Britain.[15] The movie became a word-of-mouth hit, eventually making a profit. However, it was a commercial flop in the US and was withdrawn after two days.[2][16] In his four-star review, Roger Ebert said that the film failed to open in Chicago, and attributed the problems to the Yorkshire accents.[17] Ebert saw the film at a 1972 showing organised by the Biological Honor Society at the Loyola University Chicago, which led him to ask, "were they interested in the movie, or the kestrel?" Nevertheless, he described the film as "one of the best, the warmest, the most moving films of recent years".[17]

Director Krzysztof Kieslowski named it as one of his favorite films.[18]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 100% based on 31 reviews, with an average rating of 9.56/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "A harrowing coming of age tale told simply and truly, Kes is a spare and richly humane tribute to the small pockets of beauty to be found in an oppressive world."[19]

In an essay included with the 2016 Blu-ray release of the film, commentator Philip Kent writes:

Funny, sad, and bitingly authentic, Kes resonates with Loach's anger at the way so many kids grow up into narrow, option-free lives. ... But Loach's underdogs are never sad passive victims. There's a defiant spirit about Billy, and a fierce joy in the scenes where he trains his kestrel. Kes, as Loach has commented, sets up a contrast between "the bird that flies free and the boy who is trapped", but at the same time there's an unmistakable identification between them. ... The film's ending is desolate, but we sense Billy will survive.[20]

Reflecting on changes in the film's locale and setting in the intervening 40-odd years, Graham Fuller wrote in 2011:

It [the film] has gradually achieved classic status and remains the most clear-sighted film ever made about the compromised expectations of the British working class. Its world has changed: Billy's all-white "secondary modern" school (for children who failed the national exam for eleven-year-olds) would have become a fully streamed (academically nonselective) "comprehensive" in the early seventies, and increasingly multiethnic; Barnsley's coal mines closed in the early nineties. But the film's message is relevant wherever the young are maltreated and manipulated, and wherever the labor force is exploited.[21]

Reviewing the film in 2009 for www.frenchfilms.org, James Travers wrote:

Kes is an extraordinary film, beautifully composed and searing in its realist humanity. It is often compared with François Truffaut's Les 400 coups (1959), another memorable depiction of adolescent rebellion in an unsympathetic adult world. Both films are what the French term a cri de coeur, a heartfelt appeal for adults not to write off the next generation and condemn them to a future without meaning, but rather to take the time and the effort to instil in youngsters a sense of self-worth and desire to make something of their lives. Forty years since it was first seen, Kes has lost none of its power to move an audience and remains one of the most inspired and inspirational films of the Twentieth Century.[22]

Graeme Ross, writing in 2019 in The Independent, placed the film 8th in his "best British movies of all time", saying:

A beautifully filmed adaption of the Barry Hines novel A Kestrel For a Knave with a remarkable performance from David Bradley as Billy Casper, a 15-year-old boy from a deprived background whose life is transformed when he finds a young falcon and trains it, in the process forming a close emotional bond with the bird. There's comedy and tragedy in equal measure in Kes, with the hilarious football scene with Brian Glover as both referee and Bobby Charlton and the heartbreaking ending demonstrating Loach's devastating gift for both. The cast of the mostly non-professional actors wasn't told what to expect in many of the scenes, hence the real shock and pain on the boys' faces when they were caned by the bullying headmaster. With Chris Menges' superb camerawork lit only by natural light, Kes remains a true British classic and the peak of Loach's illustrious body of work.[23]

Awards

[edit]- 1970: Karlovy Vary International Film Festival – Crystal Globe[24]

- 1971: Writers' Guild of Great Britain Award – Best British Screenplay[25]

- 1971: British Academy Film Awards[26]

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role – Colin Welland

- Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles – David Bradley

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Kes (U)". British Board of Film Classification. 27 May 1969. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ a b Walker, Alexander (1974). Hollywood UK: The British Film Industry in the Sixties (1st ed.). Stein And Day. p. 378. ISBN 978-0812815498.

- ^ "Kes". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "The BFI 100: 1-10". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 29 February 2000. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ Hines, Richard (2016). No Way But Gentlenesse: A Memoir of How Kes, My Kestrel, Changed My Life. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408868034.

- ^ "British Films at Doc Films, 2011-2012". The Nicholson Center for British Studies. University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Interview – Ken Loach (KES, 1970)". La Semaine de la critique. 15 April 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Scovell, Adam (13 April 2018). "Kes: in search of the locations for Ken Loach's classic". British Film Institute.

- ^ a b Golding, Simon W. (2006). Life After Kes: The Making of the British Film Classic, the People, the Story and Its Legacy. Shropshire, UK: GET Publishing. ISBN 0-9548793-3-3. OCLC 962416178.

- ^ Hill, John (2011). Ken Loach: The Politics of Film and Television. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-1844572038.

- ^ "Andrew Garfield: Playing Billy Casper. In Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, 2004 (Behind the Scenes with Kes)". Royal Exchange Theatre.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Correspondence from Stephen Murphy on the certification of Kes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "BBFC Case Studies – Kes". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Kes". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "Tony Garnett interview". British Entertainment History Project. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ "From the archive, 7 August 1982: Gregory's Girl gets a new accent". The Guardian. 7 August 2012. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (16 January 1973). "Kes movie review & film summary (1973)". RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "Kieślowski's cup of tea (Sight & Sound Top ten poll) – Movie List". MUBI. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Kes (1969)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Kent, Philip (2016). "Championing the underdog – Ken Loach before and after Kes". Essay included with the 2016 Blu-Ray release of Kes, Eureka Entertainment Ltd. (Masters of Cinema Series #151).

- ^ Fuller, Graham (19 April 2011). "Kes: Winged Hope". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Travers, James (2009). "Kes (1969) Film Review". frenchfilms.org.

- ^ Ross, Graeme (29 August 2019). "From Kes to Clockwork Orange, the 20 best British films". The Independent.

- ^ "17th Karlovy Vary IFF: July 15 – 26, 1970 – Awards". Karloff Vary International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "Writers' Guild Awards 1970". Writers' Guild of Great Britain. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ "Film in 1971 | BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Fuller, Graham (19 April 2011). "Kes: Winged Hope". The Criterion Collection.

- Garforth, Richard (18 October 2009). "Kes 40 years on". Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Interview with David Bradley.

- Robins, Mike (October 2003). "Kes". Senses of Cinema (28). A detailed synopsis, referenced background and review of Kes.

- Till, L.; Hines, B (2000). Kes: Play. London: Nick Hern Books. ISBN 978-1-85459-486-0.

External links

[edit]- Kes at IMDb

- Kes at Rotten Tomatoes

- Kes at the BFI's Screenonline

KSF

KSF