Largest prehistoric animals

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 126 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 126 min

The largest prehistoric animals include both vertebrate and invertebrate species. Many of them are described below, along with their typical range of size (for the general dates of extinction, see the link to each). Many species mentioned might not actually be the largest representative of their clade due to the incompleteness of the fossil record and many of the sizes given are merely estimates since no complete specimen have been found. Their body mass, especially, is largely conjecture because soft tissue was rarely fossilized. Generally, the size of extinct species was subject to energetic[1] and biomechanical constraints.[2]

Non-mammalian synapsids (Synapsida)

[edit]Caseasaurs (Caseasauria)

[edit]The herbivorous Alierasaurus was the largest caseid and the largest amniote to have lived at the time, with an estimated length around 6–7 m (20–23 ft).[3] Cotylorhynchus hancocki is also large, with an estimated length and weight of at least 6 m (20 ft)[4] and more than 500 kg (1,100 lb).[5]

Edaphosaurids (Edaphosauridae)

[edit]

The largest edaphosaurids were Lupeosaurus at 3 m (9.8 ft) long[6] and Edaphosaurus, which could reach even more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in length.[7]

Sphenacodontids (Sphenacodontidae)

[edit]The biggest carnivorous synapsid of Early Permian was Dimetrodon, which could reach 4.6 m (15 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb).[8] The largest members of the genus Dimetrodon were also the world's first fully terrestrial apex predators.[9]

Tappenosauridae

[edit]The Middle Permian Tappenosaurus was estimated at 5.5 m (18 ft) in length, nearly as large as the largest dinocephalians.[10]

Therapsids (Therapsida)

[edit]Anomodonts (Anomodontia)

[edit]

The plant-eating dicynodont Lisowicia bojani is the largest-known of all non-mammalian synapsids, at about 4.5 m (15 ft) long, 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) tall, and 9,000 kg (20,000 lb) in body mass.[11][12][13] However, in 2019 its weight was later more reliably estimated by modelling its mass from the estimated total volume of its body. These estimates varied depending on the girth of its rib cage and the amount of soft tissue modelled around the skeleton, with an overall average weight of 5.9 metric tons (6.5 short tons), and a lowermost estimate with minimal body fat and other tissues at 4.9 metric tons (5.4 short tons) and a maximum of 7 metric tons (7.7 short tons) at its bulkiest.[14]

Biarmosuchians (Biarmosuchia)

[edit]The Late Permian Eotitanosuchus (a possible synonym to Biarmosuchus[15]) may have been over 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in length, possibly up to 6 m (20 ft) and more than 600 kg (1,300 lb) in weight for adult specimens.[15]

Dinocephalians (Dinocephalia)

[edit]

- Perhaps the largest known dinocephalian was the titanosuchid Jonkeria truculenta, with volumetric models suggesting it could have weighed 985 kg (2,172 lb).[16] Tapinocaninus pamelae was slightly smaller, volumetric models suggesting it weighed 892.63 kg (1,967.9 lb).[17]

- The largest carnivorous non-mammalian synapsids was the anteosaurid Anteosaurus, which was 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long, and weighed 500–600 kg (1,100–1,300 lb).[18][19] Fully grown Titanophoneus from the same family Anteosauridae likely had a skull of 1 m (3.3 ft) long.[19]

Gorgonopsians (Gorgonopsia)

[edit]

Inostrancevia latifrons is the largest known gorgonopsian, with a skull length of more than 60 cm (24 in), a total length approaching 3.5 m (11 ft) and a mass of 300 kg (660 lb).[20] Rubidgea atrox is the largest African gorgonopsian, with skull of nearly 45 cm (18 in) long.[21] Other large gorgonopsians include Dinogorgon with skull of ~40 cm (16 in) long,[22] Leontosaurus with skull of almost 40 cm (16 in) long,[21] and Sycosaurus with skull of ~38 cm (15 in) long.[21]

Therocephalians (Therocephalia)

[edit]The largest of therocephalians is Scymnosaurus,[23][24] which reached a size of the modern hyena.[25]

Non-mammalian cynodonts (Cynodontia)

[edit]- The largest known non-mammalian cynodont, as well as the largest member of Cynognathia, is Scalenodontoides, a traversodontid, which had a maximum skull length of approximately 61.7 centimetres (24.3 in) based on a fragmentary specimen.[26]

- Paceyodon davidi was the largest of morganucodontans, cynodonts close to mammals. It is known by a right lower molariform 3.3 mm (0.13 in) in length, which is bigger than molariforms of all other morganucodontans.[27]

- The largest known docodont was Castorocauda, almost 50 cm (20 in) in length.[28]

Mammals (Mammalia)

[edit]Non-therian mammals

[edit]Gobiconodonts (Gobiconodonta)

[edit]

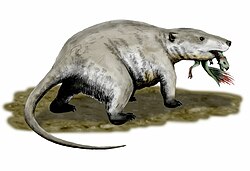

The largest gobiconodont and the largest well-known Mesozoic mammal was Repenomamus.[29][30][31][32][33][34] The known adult of Repenomamus giganticus reached a total length of around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and an estimated mass of 12–14 kg (26–31 lb).[31] With such parameters it surpassed in size several small theropod dinosaurs of the Early Cretaceous.[35] Gobiconodon was also a large mammal,[33][34] it weighed 5.4 kilograms (12 lb),[31] had a skull of 10 cm (3.9 in) in length, and had 35 cm (14 in) in presacral body length.[36]

Multituberculates (Multituberculata)

[edit]The largest multituberculate,[37] Taeniolabis taoensis is the largest non-therian mammal known, at a weight possibly exceeding 100 kg (220 lb).[38]

Monotremes (Monotremata)

[edit]

- The largest known monotreme (egg-laying mammal) ever was the extinct long-beaked echidna species known as Murrayglossus hacketti, known from a couple of bones found in Western Australia. It was the size of a sheep, weighing probably up to 30 kg (66 lb).[39]

- The largest known ornithorhynchid is Obdurodon tharalkooschild.[40]

- Kollikodon ritchiei was likely the largest monotreme in the Mesozoic. Its body length could be up to a 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[41]

Metatherians (Metatheria)

[edit]

- The largest non-marsupial metatherian, as well as the largest carnivorous metatherian, was Proborhyaena gigantea, which is estimated to have weighed weigh 50–200 kg (110–440 lb).[42][43][44][45] Another large metatherian was Thylacosmilus atrox, weighing 80 to 120 kilograms (180 to 260 lb),[46][47] with one estimate suggesting 150 kg (330 lb).[48] Australohyaena is another large metatherian, weighing up to 70 kilograms (150 lb).[49]

- Stagodontid mammal Didelphodon was one of the largest Mesozoic metatherians and all Cretaceous mammals.[50] Its skull could reach over 10 centimetres (3.9 in) in length[51] and a weight of complete animal was 5.2 kilograms (11 lb).[52]

Marsupials (Marsupialia)

[edit]

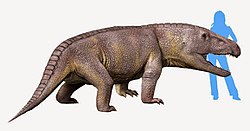

- The largest known marsupial, and the largest metatherian, is the extinct Diprotodon, about 3 m (9.8 ft) long, standing 2 m (6 ft 7 in) tall and weighing up to 2,786 kg (6,142 lb).[53] Fellow vombatiform Palorchestes azael was similar in length being around 2.5 m (8.2 ft), with body mass estimates indicating it could exceed 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[54]

- The largest known carnivorous marsupial was Thylacoleo carnifex. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show they averaged 101 to 164 kg (223 to 362 lb) in weight.[55][56] are the largest Giant koala (Phascolarctos stitorni) are modern Koala (Phascolarctos cinerus) and has an estimated weight of 13 kg (29 lb), which is the same weight as a large contemporary male koala.[57] the largest ever Sarcophilus laniarius which were around 15% larger and 50% heavier than modern devils.[58]

- The largest known kangaroo was an as yet unnamed[needs update] species of Macropus, estimated to weigh 274 kg (604 lb),[59] larger than the largest known specimen of Procoptodon, which could grow up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) and weigh 230 kg (510 lb).[60] Some species from the genus Sthenurus were similar in size or a bit larger than the extant grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus).[61] The largest ever tree kangaroo, Bohra, had an estimated body mass of 35–47 kg (77–104 lb).[62]

- The largest potoroid ever recorded was Borungaboodie, which was nearly 30% bigger than the largest living species and weighed up to 10 kg (22 lb).[63]

- The largest member of the Thylacinidae is Thylacinus megiriani, which is somewhat reasonably larger than the Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus), and bigger than its fellow Miocene relative Thylacinus potens, usually being 57.3 kilograms in weight.[64]

Non-placental eutherians

[edit]

Cimolestans (Cimolesta)

[edit]The largest known cimolestan is Coryphodon, 1 m (3 ft 3 in) high at the shoulder, 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) long[65][66] and up to 700 kg (1,500 lb) of mass.[67] Barylambda was also a huge mammal, at 650 kg (1,430 lb).[68] Wortmania and Psittacotherium from the group Taeniodonta were among the largest mammals of the Early Paleocene.[69] Lived as soon as half a million years after K–Pg boundary, Wortmania reached 20 kg (44 lb) in body mass. Psittacotherium, which appeared two million years later, reached 50 kg (110 lb).[69]

Leptictids (Leptictida)

[edit]The largest leptictid ever discovered is Leptictidium tobieni from the Middle Eocene of Germany. It had a skull 101 mm (4.0 in) long, head with trunk 375 mm (14.8 in) long, and tail 500 mm (20 in) long.[70] Close European relatives from the same family Pseudorhyncocyonidae had skulls of 67–101 mm (2.6–4.0 in) in length.[70]

Tenrecs and allies (Afroscida)

[edit]The larger of the two species of bibymalagasy (Plesiorycteropus madagascariensis), extinct tenrec relatives from Madagascar, is estimated to have weighed from 10 to 18 kilograms (21 to 40 lb).[71]

Even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla)

[edit]

- The largest known land-dwelling artiodactyl was Hippopotamus gorgops estimated to have weighed over 4,000 kg (8,800 lb),[72] with its closely related European descendant, Hippopotamus antiquus, possibly rivaling it, estimated to be 14.1 ft (4.3 m) in length and 3,500–4,200 kg (7,700–9,300 lb) in weight.[73] However, volumetric models suggests it was slightly smaller, weighing 3,174 kilograms (6,997 lb).[74]

- Daeodon and similar in size and morphology Paraentelodon[75] were the largest-known entelodonts that ever lived, at 3.7 m (12 ft) long and 1.77 m (5.8 ft) high at the shoulder.[76] The huge Andrewsarchus from the Eocene of Inner Mongolia had a skull about 83.4 cm (32.8 in) long[77] though the taxonomy of this genus is disputed.[78][79]

- The largest of Bovinae as well as the largest bovid was Bison latifrons. It reached a weight from 1,250 kg (2,760 lb)[80][81] to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb),[82] 4.75 m (15.6 ft) in length, shoulder height of 2.31 m (7.6 ft),[83] and had horns that spanned 2.13 m (7 ft 0 in).[84] The North American Bison antiquus reached up to 4.6 m (15 ft) long, 2.27 m (7.4 ft) tall, weight of 1,588 kg (3,501 lb),[85] and horn span of 1 m (3.3 ft).[83] The African Pelorovis reached 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight and had bony cores of the horns about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long.[86] Another enormous bovid, the african giant buffalo (Syncerus antiquus) reached 3 m (9.8 ft) in length from muzzle to the end of the tail, 1.85 m (6.1 ft) in height at the withers, 1.7 m (5.6 ft) in height at the hindquarters,[87][88] and the distance between the tips of its horns was as large as 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in).[87] Aside from local populations and subspecies of extant species, such as the gaur population in Sri Lanka, European bison in British Isles, Caucasian wisent and Carpathian wisent, the largest modern extinct bovid is aurochs (Bos primigenius) with an average height at the shoulders of 155–180 cm (61–71 in) in bulls and 135–155 cm (53–61 in) in cows, while aurochs populations in Hungary had bulls reaching 155–160 cm (61–63 in).[89] The kouprey (Bos sauveli), reaching 1.7–1.9 m (5 ft 7 in – 6 ft 3 in) in shoulder height,[90][91] has existed since the Middle Pleistocene[92] and is also considered to be possibly extinct.[93][94]

- The long-legged Megalotragus is possibly the largest known alcelaphine bovid,[95] bigger than the extant wildebeest.[96] The tips of horns of M. priscus were located at a distance of about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) from each other.[97]

- The extinct cervid Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) reached over 2.1 m (7 ft) in height, 680 kg (1,500 lb) in mass and could have antlers spanning up to 4.3 m (14 ft) across, about twice the maximum span for a moose's antlers.[98][99] The giant moose (Cervalces latifrons) reached 2.1 to 2.4 m (6.9 to 7.9 ft) high[100] and was twice as heavy as the Irish elk but its antler span at 2.5 m (8.2 ft) was smaller than that of Megaloceros.[101][102] North American stag-moose (Cervalces scotti) reached 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length and a weight of 708.5 kilograms (1,562 lb).[103][104]

- The largest known giraffid, aside from the extant giraffe, is Sivatherium, with a body weight of 1,250 kg (2,760 lb).[105]

- The largest protoceratid was Synthetoceras, it reached 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long and 150–200 kg (330–440 lb) in mass.[106][107]

- The largest known wild suid to ever exist was Kubanochoerus gigas, having measured up to 500 kg (1,100 lb) and stood around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall at the shoulder.[108] Megalochoerus could be similar in size, possibly weighing 303 kg (668 lb) or 526 kg (1,160 lb).[109]

- The largest tayassuid extinct Platygonus species were similar in size to modern peccaries especially giant peccary, at around 1 m (3.3 ft) in body length, and had long legs, allowing them to run well. They also had a pig-like snout and long tusks which were probably used to fend off predators.[110]

- The largest camelid was Titanotylopus from the Miocene of North America. It possibly reached 2,485.6 kg (5,480 lb) and a shoulder height of over 3.4 m (11 ft).[111][112] The Syrian camel (Camelus moreli) was twice as big as the modern camels.[113] It was 3 m (9.8 ft) at the shoulder[114] and 4 m (13 ft) tall.[113] Camelops had legs 20% longer than that of the dromedary and was about 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) tall at the shoulder, weighing about 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[115]

- The anoplotheriid Anoplotherium is thought to have been capable of reaching up to 271 kg (597 lb) in the case of A. commune and 229 kg (505 lb) in the case of A. latipes.[116] A. latipes in particular could have measured more than 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in length and 1.25 m (4 ft 1 in) in shoulder height. Because it was probably capable of facultative bipedalism, it could have been capable of standing over 3 m (9.8 ft) tall.[117]

Cetaceans (Cetacea)

[edit]

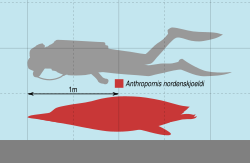

- The heaviest archeocete was Perucetus, with weight estimated at 85–340 t (84–335 long tons; 94–375 short tons), while length is estimated at 17.0–20.1 meters (55.8–65.9 ft).[118] However, Motani and Pyenson in 2024 argued that it is extremely difficult for Perucetus to rival or exceed the blue whale in weight. They discussed that since Perucetus is much shorter than the blue whale in length, it should be at least 3.375 times denser or 1.83 times fatter to weigh heavier, which is impossible for vertebrates whose whole-body density range from 0.75 to 1.2. Motani and Pyenson tested the hypotheses of Bianucci and colleagues by performing various body mass estimation methods: the regression-based and volumetric mass estimation resulted in 60–114 t (59–112 long tons; 66–126 short tons) for a length range of 17–20 m (56–66 ft), though the likely body mass range would fall within 60–70 t (59–69 long tons; 66–77 short tons) . They also claimed that the previous estimation is inflated by assumed isometry, and that the effect from pachyostosis on the estimation of body mass is not negligible as it resulted in underestimation.[119] The longest of known Eocene archeocete whales was Basilosaurus at 17–20 m (56–66 ft) in length.[120][121][122]

- The largest squalodelphinid was Macrosqualodelphis at 3.5 m (11 ft) in length.[123]

- Some Neogene rorquals were comparable in size to modern huge relatives. Parabalaenoptera was estimated to be about the size of the modern gray whale,[124] about 16 m (52 ft) long. Some balaenopterids perhaps rivaled the blue whale in terms of size,[124] though other studies disagree that any baleen whale grew that large in the Miocene.[125]

- The largest macroraptorial sperm whale is Livyatan, with an estimated length of 44–57 ft (13.5–17.5 m) and an estimated weight of 62.8 short tons (57 tonnes).[126]

- The largest dolphin is Orcinus paleorca, a Pleistocene relative of the modern Orca (Orcinus orca). The tooth is conical and belonged to the upper right or lower left jaw of an adult individual. The tooth fragment is 5 cm (2.0 in) in height–though the actual height may have been double that–2.25 cm (0.89 in) longitudinally–from the side facing the tongue to the side facing the lip–and 2.95 cm (1.16 in) transversely–from the left side of the tooth to the right.[127] In comparison, the modern killer whale has teeth around 8 cm (3.1 in) in height and 2.5 cm (0.98 in) in diameter.[128] Like the modern killer whale, the tooth lacks a coat of cementum. However, unlike the modern killer whale, O. paleorca had a circular tooth root as opposed to an oval, and the pulp extended more towards the back than the front.[127]

Odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla)

[edit]

- One of the largest known perissodactyls, and the second largest land mammal (see Palaeoloxodon namadicus) of all time was the hornless rhino Paraceratherium. The largest individual known was estimated at 4.8 m (15.7 ft) tall at the shoulders, 7.4 m (24.3 ft) in length from nose to rump, and 17 t (18.7 short tons) in weight.[129][130] A large specimen of an unnamed species of the related Dzungariotherium has been estimated to be around 20.6 metric tonnes.[131]

- Some prehistoric horned rhinos also grew to large sizes. The biggest Elasmotherium reached up to 5–5.2 m (16–17 ft) long,[132] 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) high[133] and weighed 3.5–5 t (3.9–5.5 short tons).[134][132][133] Such parameters make it the largest rhino of the Quaternary.[134] Woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) of the same time reached 1,100–1,500 kg (2,400–3,300 lb)[135] or 2,000 kg (4,400 lb),[136][137] 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in) at the shoulder height and 4.6 m (15 ft) in length.[138]

- Metamynodon, an amynodontid, reached 4 m (13 ft) in length, comparable to Hippopotamus in measurement and shape.[139]

- The giant tapir (Tapirus augustus) was the largest tapir ever, at about 623 kg (1,373 lb)[140] and 1 m (3.3 ft) tall at the shoulders.[141] Earlier, this mammal was estimated even bigger, at 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall, and assigned to the separate genus Megatapirus.[141]

- The largest known lophiodont is Lophiodon, with L. lautricense being estimated to reach more than 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) in weight.[142]

- One of the biggest chalicotheres was Moropus.[143] It stood about 2.4 metres (8 ft) tall at the shoulder.[144]

- Late Eocene perissodactyls from the family Brontotheriidae attained huge sizes. The North American Megacerops (also known as Brontotherium[145]) reached 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) tall at the shoulders,[146] 5 m (16 ft) in length,[145] and 3–3.5 t (6,600–7,700 lb) in weight.[147][148]Embolotherium from Asia was equal in size.[149]

- The largest prehistoric horse was Equus giganteus of North America. It was estimated to grow to more than 1,250 kg (1.38 short tons) and 2 m (6 ft 7 in) at the shoulders.[150] The largest anchitherine equid was Hypohippus at 403 to 600 kg (888 to 1,323 lb), comparable to large modern domestic horses.[151][152] Megahippus is another large anchitheriine. With the body mass of 266.2 kg (587 lb) it was much heavier than most of its close relatives.[151]

- Among the largest-sized genera of palaeotheres, close relatives of horses, is Palaeotherium, with P. giganteum being estimated to reach weights of more than 700 kg (1,500 lb).[153] Previously until the naming of P. giganteum in 1994, P. magnum was considered the largest species of Palaeotherium,[154] potentially reaching 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) in shoulder height and 2.52 m (8 ft 3 in) in length.[155] Another palaeothere Cantabrotherium is estimated to have weighed about 600 kg (1,300 lb).[153]

Phenacodontids (Phenacodontidae)

[edit]The largest known phenacodontid is Phenacodus. It was 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) long[156] and weighed up to 56 kg (123 lb).[157]

Dinoceratans (Dinocerata)

[edit]The largest known dinoceratan was Eobasileus with skull length of 102 cm (40 in), 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) tall at the back and 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder.[158] Another huge animal of this group was Uintatherium, with skull length of 76 cm (30 in), 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder,[158] 4 m (13 ft) in length and 2.25 t (2.48 short tons), the size of a rhinoceros.[159] Despite their large size, Eobasileus as well as Uintatherium had a very small brain.[158][159]

Carnivores (Carnivora)

[edit]Caniformia

[edit]

- The largest terrestrial mammalian predator, as well the largest known bear and terrestrial carnivoran of all time was Arctotherium angustidens, the South American short-faced bear. A humerus of A. angustidens from Buenos Aires indicates that the males of the species could have weighed 1,588–1,749 kg (3,501–3,856 lb) and stood at least 3.4 m (11 ft) tall on their hind-limbs.[160][161] Another huge bear was the giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), with the average weight of 625 kg (1,378 lb) and the maximum estimated at 957 kg (2,110 lb).[162] There is a guess that the largest individuals of this species could reached even larger mass, up to 1,200 kg (2,600 lb).[160] The extinct cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) was also heavier than many recent bears. Largest males weighed as much as 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[163] The largest males of the possibly disrupted subspecies of brown bear (Ursus arctos), steppe brown bear (Ursus arctos priscus), is also estimated to have weighed 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[164] Another large bear was Agriotherium africanum, this species was estimated to have initially estimated to have weighed 750 kilograms (1,650 lb),[165][166] but more recent estimates suggest it could’ve weighed 317–540 kilograms (699–1,190 lb).[167][48] Ailuropoda baconi from the Pleistocene was larger than the modern giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca).[168]

- The biggest odobenid and one of the biggest pinnipeds to have ever existed is Pontolis magnus, with a skull length of 60 cm (24 in) (twice as large as the skulls of modern male walruses)[169] and having a total body length of more than 4 m (13 ft).[170][171] Only the modern male elephant seals (Mirounga) reach similar sizes.[170] The second largest prehistoric pinniped is Gomphotaria pugnax with a skull length of nearly 47 cm (19 in).[169]

- One of the largest of prehistoric otariids is Thalassoleon, comparable in size to the biggest extant fur seals. An estimated weight of T. mexicanus is no less than 295–318 kg (650–701 lb).[172]

- The biggest known mustelid to ever exist was likely the giant otter, Enhydriodon omoensis. It exceeded 3 m (9.8 ft) in length, and would have weighed in at around 200 kg (440 lb), much larger than any other known mustelid, living or extinct.[173][174][175] There were other giant otters, like Siamogale, at around 50 kg (110 lb)[176] and Megalenhydris, which was larger than a modern-day giant river otter.[177] Megalictis was the largest purely terrestrial mustelid[178] (although Enhydriodon had recently been mentioned as the largest mustelid that also happens to be a terrestrial predator[173]). Similar in size to the jaguar, Megalictis ferox had even wider skull, almost as wide as of the black bear.[178] Another large-bodied mustelid was the superficially cat-like Ekorus from the Miocene of Africa. At almost 44 kg (97 lb), the long-legged Ekorus was about the size of a wolf.[179] Other huge mustelids include Perunium[180] and hypercarnivorous Eomellivora, both from the Late Miocene.[181]

- The heaviest procyonid was possibly the South American Chapalmalania. It reached 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in body length with a short tail and 150 kilograms (330 lb), comparable in size to an American black bear (Ursus americanus).[182] Another huge procyonid was Cyonasua, which weighted about 15–25 kg (33–55 lb), about the same size as a medium-sized dog.[183]

- The largest canid of all time was Epicyon haydeni, which stood 90 cm (35 in) tall at the shoulder, had a body length of 2.4 m (7.9 ft) and weighed 100–125 kg (220–276 lb),[184][185][186] with the heaviest known specimen weighing up to 170 kg (370 lb).[48] The extinct dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) reached 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length and weighed between 50 and 110 kg (110 and 243 lb).[48][187] The largest wolf (Canis lupus) subspecies ever existed in Europe is the Canis lupus maximus from the Late Pleistocene of France. Its long bones are 10% larger than those of extant European wolves and 20% longer than those of C. l. lunellensis.[188] The Late Pleistocene Italian wolf was morphometrically close to C. l. maximus.[189]

- The largest amphicyonid (bear-dogs) was a species of Pseudocyon weighing around 773 kg (1,704 lb), representing a very large individual.[190]

Feliformia

[edit]

- The largest definitive nimravid was Quercylurus major as its fossils suggest it weighed 200 kg (440 lb) similar in size to the modern-day lion and was scansorial. The closely related Dinailurictis bondali was slightly smaller weighing 130 kg (290 lb), making it as large as a lioness.[191] Eusmilus adelos was the largest of the hoplophonine nimravid, reaching a weight of 111 kg (245 lb), comparable to a small African lion.[192] While it was assumed that Hoplophoneus occidentalis could’ve weighed 160 kg (350 lb),[48] other experts suggested it was smaller,[192] being about the size of a leopard.[193] A 2012 study suggested this species could’ve weighed 65 kg (143 lb).[194]

- The largest barbourofelid was Barbourofelis fricki, with the shoulder height of 90 cm (35 in) and could’ve weighed 328 kg (723 lb).[192][195] If recent phylogeny is accurate, then this would make B. fricki the largest known nimravid.[196][197]

- The largest machairodont (saber-toothed cats) felid was Amphimachairodus kabir, with the males possibly reaching 350–490 kg (770–1,080 lb).[198] Smilodon populator was a close contender, with males weighing 220–450 kg (490–990 lb).[48][199] Another large member of the Amphimachairodus genus, A. horribilis,[200][201] is estimated to weigh 405 kg (893 lb).[202] Another contender is Nimravides catocopis[203] with the largest specimen weighing up to 427 kg (941 lb).[204] An unnamed species of Xenosmilus thought to have weighed between 347–410 kilograms (765–904 lb).[205]

- The heaviest known pantherine felids were the extinct leonines Panthera fossilis, which has been estimated to have maximum weight of 400–500 kg (880–1,100 lb),[206] the American lion (Panthera atrox), weighing up to 363 kg (800 lb),[207][208] and the Natodomeri lion of eastern Africa, which was comparable in size to large members of P. atrox.[209] The Ngangdong tiger (Panthera tigris soloensis), was estimated to have weighed up to 486 kg (1,071 lb),[199] however this has been contested with some estimates suggesting the largest individuals weighed 298 kg (657 lb).[210]

- The largest feline felid was Acinonyx pleistocaenicus, with the largest specimen weighing 188 kg (414 lb).[211] Its close relative, giant cheetah (Acinonyx pardinensis), reached 60–121 kg (132–267 lb), approximately twice as large as the modern cheetah.[212] The North American Pratifelis was larger than the extant cougar.[213]

- The largest viverrid known to have existed is Viverra leakeyi, which was around the size of a wolf or small leopard at 41 kg (90 lb).[214]

- The largest known extinct hyena was the percrocutid hyena[215][216][217], Dinocrocuta gigantea. It was originally estimated to have weighed 380 kg (840 lb).[218] However, recent weight estimates may suggest it may have weighed less. An individual with a skull length of 32.2 cm (12.7 in), is estimated to have weighed 200 kg (440 lb).[219] One specimen is reported to have a skull length of 40 cm (16 in).[220] Pachycrocuta brevirostris was another large extinct hyena. It’s estimated at 90–100 cm (35–39 in) at the shoulder[221] and 190 kg (420 lb) weight.[48] However, other experts leaned towards 150 kg (330 lb) representing the upper end of the species.[222] Crocuta hyenas have also been known large sizes, even larger than the extant spotted hyena, most notably the extinct spotted hyena subspecies, the cave hyena, with average individuals weighing 88 kg (194 lb).[223] Crocuta eturno was another large Crocuta species with estimates suggesting this species could’ve weighed 85 kg (187 lb).[224]

- The extinct giant fossa (Cryptoprocta spelea) had a body mass in range from 17 kg (37 lb)[225] to 20 kg (44 lb),[226] much larger than the modern fossa weighs (up to 8.6 kg (19 lb) for adult males[227]).

Hyaenodonts (Hyaenodonta)

[edit]- The largest hyainailourid, as well as the largest hyaenodont was Megistotherium osteothlastes at 500–880 kg (1,100–1,940 lb).[228][48] While it’s close relative, Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, was estimated to reach 208–1,554 kg (459–3,426 lb), the same regression suggested Megistotherium was larger than Simbakubwa.[229] Hyainailouros was another large hyainailourid. The largest species in the genus, H. bugtiensis, which could’ve weighed between 267–1,744 kg (589–3,845 lb).[229]

- The largest hyaenodontid was Hyaenodon gigas, weighing in at around 378 kg (833 lb).[230]

Oxyaenids (Oxyaenidae)

[edit]

The largest known oxyaenid was Sarkastodon weighing in at 800 kg (1,800 lb).[48]

Mesonychians (Mesonychia)

[edit]Some mesonychians reached a size of a bear. Such large were Mongolonyx from Asia[231] and Ankalagon from North America.[232][233] Another large mesonychian is Harpagolestes with a skull length of a half a meter in some species.[231]

Bats (Chiroptera)

[edit]Found in Quaternary deposits of South and Central Americas, Desmodus draculae had a wingspan of 0.5 m (20 in) and a body mass of up to 60 g (2.1 oz). Such proportions make it the largest vampire bat that ever evolved.[234]

Hedgehogs, gymnures, shrews, and moles (Eulipotyphla)

[edit]

The largest known animal of the group Eulipotyphla was Deinogalerix,[235] measuring up to 60 cm (24 in) in total length, with a skull up to 21 cm (8.3 in) long.[236]

Rodents (Rodentia)

[edit]

- Several of the extinct South American dinomyids were much bigger than modern rodents. Josephoartigasia monesi was the largest-known rodent of all time, approximately weighing an estimated 480–500 kg (1,060–1,100 lb).[237] Phoberomys pattersoni weighed 125–150 kg (276–331 lb).[237] Both Josephoartigasia and Phoberomys reached about 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder.[238] Another huge dinomyid, Telicomys gigantissimus had a minimal weight of 200 kg (440 lb).[238]

- Amblyrhiza inundata from the family Heptaxodontidae was a massive animal, it weighed 50–200 kg (110–440 lb).[239][238]

- The largest beaver was the giant beaver (Castoroides) of North America. It grew over 2 m in length and weighed roughly 90 to 125 kg (198 to 276 lb), also making it one of the largest rodents to ever exist.[240]

- The largest old world porcupine are the Hystrix refossa was larger than living porcupines. It was approximately 20% larger than its closest relative, the living Indian porcupine (H. indica), reaching lengths of over 115 cm (45 in).

Rabbits, hares, and pikas (Lagomorpha)

[edit]The biggest known prehistoric lagomorph is Minorcan giant lagomorph Nuralagus rex at 12 kg (26 lb).[241]

Pangolins (Pholidota)

[edit]The largest pangolin was the extinct Manis palaeojavanica[242] Its total length is measured up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft).[243]

Primates (Primates)

[edit]

- The largest known non-hominid primate is Gigantopithecus blacki. Studies estimate heights around 2.74–3.66 m (9 ft 0 in – 12 ft 0 in) tall, weighing 225–300 kg (496–661 lb).[244][245][246] Some suggested that it would not exceed 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) tall with a bipedal posture.[247] Another giant ape-like hominid was Meganthropus palaeojavanicus at 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) in body height,[248] although it is known from very poor remains.[249]

- During the Pleistocene, some archaic humans were close in sizes or even larger than early modern humans. Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) reached 77.6 kg (171 lb) and 66.4 kg (146 lb) in average weight for males and females, respectively, larger than the parameters of modern humans (Homo sapiens) (68.5 kg (151 lb) and 59.2 kg (131 lb) for males and females, respectively).[250] A tibia from Kabwe (Zambia) indicates an indeterminate Homo individual of possibly 181.2 cm (71.3 in) in height. It was one of the tallest humans of the Middle Pleistocene and noticeably large even compared to recent humans.[251] The tallest Homo sapiens individuals from the Middle Pleistocene of Spain reached 194 cm (76 in) and 174 cm (69 in) for males and females, respectively.[251] Some Homo erectus could be as large as 185 cm (73 in) tall and 68 kg (150 lb) in weight.[252][253]

- The heaviest known Old World monkey is the prehistoric baboon is Theropithecus oswaldi which have weighed 72 kg (159 lb),[254] some even suggested to reach 128 kg (282 lb).[255] A male specimen of Dinopithecus projected to weigh an average of 46 kg (101 lb) and up to 57 kg (126 lb), exceeds the maximum weight record of the chacma baboon, the largest extant baboon.[255]

- The largest known New World monkey was Cartelles, which is studied as specimen of Protopithecus, weighing up to 34.27 kg (75.6 lb). Caipora bambuiorum is another large species, weighing up to 27.74 kg (61.2 lb).[256]

- The largest omomyids were Macrotarsius and Ourayia from the Middle Eocene. Both reached 1.5–2 kg (3.3–4.4 lb) in weight.[257]

- Some prehistoric lemuriform primates grew to huge sizes as well. Archaeoindris was a 1.5-metre-long (4.9 ft) sloth lemur that lived in Madagascar and weighed 150–187.8 kg (331–414 lb),[258] as large as an adult male gorilla.[259] Palaeopropithecus from the same family was also heavier than most modern lemurs, at 25.8–45.8 kg (57–101 lb).[260] Megaladapis is another large extinct lemur at 1.3 to 1.5 m (4 ft 3 in to 4 ft 11 in) in length[citation needed] and an average body mass of around 140 kg (310 lb).[261] Other estimates suggest 46.5–85.1 kg (103–188 lb) but its still much larger than any extant lemur.[260]

Elephants, mammoths, and mastodons (Proboscidea)

[edit]

- The elephant Palaeoloxodon namadicus has been suggested to have been the largest land mammal ever, based on a particularly large partial femur which was estimated to have belonged to an individual 22 t (24.3 short tons) in weight and about 5.2 m (17.1 ft) tall at the shoulder, though the author of the estimate said that this was speculative and should be treated with caution.[129] In 2023, a publication by Gregory S. Paul and Larramendi estimated that another specimen identified as cf. P. namadicus, also only known from a partial femur, would have weighed 18–19 tonnes (40,000–42,000 lb). Other authors have noted that weight estimates for proboscideans based on single bones can lead to estimates that are "highly improbable" compared to accurate estimates from complete skeletons.[262] In 2024, Biswas, Chang and Tsai estimated a maximum shoulder height of over 4.5 metres (15 ft) and suggested that the body mass for 5 measured specimens ranged from 13.2 to 18.5 tonnes (29,000 to 41,000 lb) from specimens from Taiwan.[263] The largest individual reported individual of the steppe mammoth of Eurasia (Mammuthus trogontherii) was estimated to reach 4.5 m (14.8 ft) at the shoulders and 14.3 t (15.8 short tons) in weight.[129][264] Stegodon zdanskyi, the biggest species of Stegodon, was 13 t (14.3 short tons) in body mass.[129] Another enormous proboscidean is Stegotetrabelodon syrticus, over 4 m (13 ft) in height and 11 to 12 t (12.1 to 13.2 short tons) in weight.[129] The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) was about 4 m (13.1 ft) tall at the shoulder but didn't weigh as much as other huge proboscideans. Its average mass was 9.5 t (10.5 short tons) with one unusually large specimen about 12.5 t (13.8 short tons).[129]

- The mammutid "Mammut" borsoni is one of the largest known proboscideans and land mammals. The average fully-grown male is estimated to have been 4.1 m (13 ft) tall and weighed about 16 t (17.6 short tons), with very large males possibly rivalling the estimated size of the largest Palaeoloxodon namadicus.[129] This species also had the longest tusks of any animals with the largest recorded specimen being 5.02 m (16.5 ft) long from basis to tip along the curve.[265]

- Deinotherium was the largest proboscidean in Deinotheriidae family. Bones retrieved in Crete confirm the existence of specimen 4.1 m (13 ft) tall at the shoulders and more than 14 t (15.4 short tons) in weight.[129]

Sea cows (Sirenia)

[edit]According to reports, Steller's sea cows have grown to 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft) long as adults, much larger than any extant sirenians.[266] The weight of Steller's sea cows is estimated to be 8–10 t (8.8–11.0 short tons).[267]

With its direct ancestor, the Cuesta sea cow being around 9 m (30 ft) long and possibly 10 tonnes (11 short tonnes) in weight.[268]

Arsinoitheres (Arsinoitheriidae)

[edit]

The largest known arsinoitheriid was Arsinoitherium. A. zitteli would have been 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) tall at the shoulders, and 3 m (9.8 ft) long.[269][270] A. giganteum reached even larger size than A. zitteli.[271]

Hyraxes (Hyracoidea)

[edit]Some of the prehistoric hyraxes were extremely large compared to modern small relatives. The largest hyracoid ever evolved is Titanohyrax ultimus.[272] With the mass estimation in rage of 600 kg (1,300 lb) to over 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) it was close in size to Sumatran rhinoceros.[273] Another enormous hyrax is Megalohyrax which had skull of 391 mm (15.4 in) in length[274] and reached the size of tapir.[272][275] More recent Gigantohyrax was three times as large as the extant relative Procavia capensis,[276] although it is noticeably smaller than earlier Megalohyrax and Titanohyrax.[277]

Desmostylians (Desmostylia)

[edit]

The largest known desmostylian was a species of Desmostylus, with skull length of 81.8 cm (32.2 in) and comparable in size to the Steller's sea cow.[278]

Paleoparadoxia is also known as one of the largest desmostylians, with body length of 3.03 m (9.9 ft).[279]

Glyptodonts, armadillos and pampatheres (Cingulata)

[edit]The largest cingulate known is Doedicurus, at 4 m (13 ft) long, 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) high[159] and reaching a mass of approximately 1,910 to 2,370 kg (2.11 to 2.61 short tons).[citation needed] The largest species of Glyptodon, Glyptodon clavipes, reached 3–3.3 m (9.8–10.8 ft) in length[280][159] and 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight.[citation needed]

Anteaters and sloths (Pilosa)

[edit]The largest known pilosan was the megatheriinae Eremotherium laurillardi, a ground sloth that was initially estimated to weigh up to 6.55 t (7.22 short tons) and a length of up to 6 m (20 ft),[281] which is as big as a bull African bush elephant. However, many studies have gotten lower estimates, with one study suggesting that 4.49 t (4.95 short tons)was the most accurate size estimate for an adult.[282] The closely related ground sloth, Megatherium americanum, was slightly smaller with volumetric models suggesting it could’ve weighed 3.7 t (4.1 short tons).[283]

Astrapotherians (Astrapotheria)

[edit]Some of the largest known astrapotherians weighed about 3–4 t (3.3–4.4 short tons), including the genus Granastrapotherium[284] and some species of Parastrapotherium (P. martiale).[285] The skeleton remains suggest that the species Hilarcotherium miyou was even larger, with a weight of 6.456 t (7.117 short tons).[286]

Litopterns (Litopterna)

[edit]The largest known litoptern was Macrauchenia, which had three hoofs per foot. It was a relatively large animal, with a body length of around 3 m (9.8 ft).[287]

Notoungulates (Notoungulata)

[edit]The largest notoungulate known of complete remains is Toxodon. It was about 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) in body length, and about 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) high at the shoulder and resembled a heavy rhinoceros. Although incomplete, the preserved fossils suggest that Mixotoxodon were the most massive member of the group, with a weight about 3.8 t (4.2 short tons).[288]

Pyrotherians (Pyrotheria)

[edit]The largest mammal of the South American order Pyrotheria was Pyrotherium at 2.9–3.6 m (9 ft 6 in – 11 ft 10 in) in length and 1.8–3.5 t (4,000–7,700 lb) in weight.[289]

Reptiles (Reptilia)

[edit]Lizards and snakes (Squamata)

[edit]

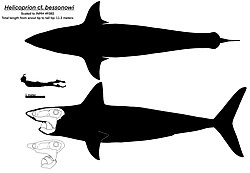

- Mosasaurs are the largest-known squamates. The largest-known mosasaur is likely Mosasaurus hoffmanni, estimated at more than 17 m (56 ft) in length,[290][291] however these estimations are based on heads and total body length ratio 1:10, which is unlikely for Mosasaurus, and probably that ratio is about 1:7.[292] Another giant mosasaur is Tylosaurus, estimated at 10–14 m (33–46 ft) in length.[293][294] Another mosasaur, Prognathodon reached similar sizes.

- The largest known prehistoric snake is Titanoboa cerrejonensis, estimated at 12.8 m (42 ft) or even 14.3 m (47 ft)[295] in length and 730–1,135 kg (1,609–2,502 lb).[296][297]The madtsoiid Vasuki indicus may have rivaled or surpassed Titanoboa in length, however had smaller vertebral dimensions compared to it.[298] A close rival in size to those snakes is palaeophiid marine snake Palaeophis colossaeus, which may have been around 9 m (30 ft) in length[296][299][300] or even up to 12.3 m (40 ft).[301] Another known very large fossil snake is Gigantophis garstini, estimated at 9.3–10.7 m (31–35 ft) in length,[302][303] although later study shows smaller estimation about 6.6–7.2 m (22–24 ft).[304] The largest fossil python is Liasis dubudingala with length roughly 9 m (30 ft).[305] The largest viper as well as the largest venomous snake ever recorded is Laophis crotaloides from the Early Pliocene of Greece. This snake reached over 3 m (9.8 ft) in length and 26 kg (57 lb) in weight.[306][307] Another huge fossil viper is indeterminate species of Vipera. With a length of around 2 m (6 ft 7 in) it was one of the biggest predators of Mallorca during the Early Pliocene.[308] The largest known blind snake is Boipeba tayasuensis with estimated total length of 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in).[309]

- The largest known land lizard is probably megalania (Varanus priscus) at 7 m (23 ft) in length.[310] As extant relatives, megalania could have been venomous and in that case this lizard was also the largest venomous vertebrate ever evolved.[311] However, maximum size of this animal is subject to debate.[312] Recent studies have estimated it at 5.5 m (18 ft) long.[313]

Turtles, tortoises and close relatives (Pantestudines)

[edit]Cryptodira

[edit]- The largest known turtle ever was Archelon ischyros at 5 m (16 ft) long and 2,200 kg (4,900 lb).[314] Possible second-largest sea turtle was Protostega at 3.9 m (13 ft) in total body length.[315][316] There is even a larger specimen of this genus from Texas estimated at 4.2 m (14 ft) in total length.[317][315] Partially known Cratochelone is estimated to reach 4 m (13 ft) in total length.[318] Another huge prehistoric sea turtle is the Late Cretaceous Gigantatypus, estimated at over 3.5 m (11 ft) in length.[319] Psephophorus terrypratchetti from the Eocene attained 2.3–2.5 m (7.5–8.2 ft) in body length.[320]

- The largest tortoise was Megalochelys atlas at up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in shell length[321] and weighing 0.8–1.0 t (1,800–2,200 lb).[147] M. margae had carapace of 1.4–2 m (4.6–6.6 ft) long; an unnamed species from Java reached at least 1.75 m (5.7 ft) in carapace length.[322] The Cenozoic Titanochelon were also larger than extant giant tortoises, with a shell length of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in).[323][324] Other giant tortoises include Centrochelys marocana at 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) in carapace length and Mesoamerican Hesperotestudo sp. at 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in carapace length.[322]

- The largest trionychid ever recorded is indeterminate specimen GSP-UM 3019 from the Middle Eocene of Pakistan. Bony carapace of GSP-UM 3019 is 120 cm (3.9 ft) long and 110 cm (3.6 ft) wide indicates the total carapace diameter (with soft margin) about 2 m (6.6 ft).[325] Drazinderetes tethyensis from the same formation had a bony carapace 80 cm (2.6 ft) long and 70 cm (2.3 ft) wide.[325] Another huge trionychid is North American Axestemys byssinus at over 2 m (6.6 ft) in total length.[326]

Side-necked turtles (Pleurodira)

[edit]

The largest freshwater turtle of all time was the Miocene podocnemid Stupendemys, with an estimated parasagittal carapace length of 2.86 m (9 ft 5 in) and weight of up to 1,145 kg (2,524 lb).[327] Carbonemys cofrinii from the same family had a shell that measured about 1.72 m (5 ft 8 in),[328][329][330] complete shell was estimated at 1.8 m (5.9 ft).[331]

Macrobaenids (Macrobaenidae)

[edit]The largest macrobaenids were the Early Cretaceous Yakemys, Late Cretaceous Anatolemys, and Paleocene Judithemys. All reached 70 cm (2.3 ft) in carapace length.[332]

Meiolaniformes

[edit]

The largest meiolaniid was Meiolania. Meiolania platyceps had a carapace 100 cm (3.3 ft) long[322] and probably reached over 3 m (9.8 ft) in total body length.[333] An unnamed Late Pleistocene species from Queensland was even larger, up to 200 cm (6.6 ft) in carapace length.[322] Ninjemys oweni reached 100 cm (3.3 ft) in carapace length[322] and 200 kg (440 lb) in weight.[334]

Sauropterygians (Sauropterygia)

[edit]Placodonts and close relatives (Placodontiformes)

[edit]Placodus was among the largest placodonts, with a length of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[335]

Nothosaurs and close relatives (Nothosauroidea)

[edit]The largest nothosaur as well as the largest Triassic sauropterygian was Nothosaurus giganteus at 7 m (23 ft) in length.[336]

Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria)

[edit]- The largest known plesiosauroid was an indeterminate specimen possibly belonging to Aristonectes (identified as cf. Aristonectes sp.), with a body length of 11–11.9 metres (36–39 ft) and body mass of 10.7–13.5 metric tons (11.8–14.9 short tons).[337] Another long plesiosauroid was Albertonectes at 11.2–11.6 metres (37–38 ft).[338] Thalassomedon rivaled it in size, with its length at 10.86–11.6 m (35.6–38.1 ft).[339] Other large plesiosauroids are Styxosaurus and Elasmosaurus. Both reached some more than 10 m (33 ft) in length.[340][341] Hydralmosaurus (previously synonymized with Elasmosaurus and Styxosaurus) reached 9.44 m (31.0 ft) in total body length.[341] In past, Mauisaurus was considered to be more than 8 m (26 ft) in length,[342][341] but later it was determined as nomen dubium.[343]

- There is much controversy over the largest-known of the Pliosauroidea. Pliosaurus funkei (also known as "Predator X") is a species of large pliosaur, known from remains discovered in Norway in 2008. This pliosaur has been estimated at 10–13 m (33–43 ft) in length.[344] However, in 2002, a team of paleontologists in Mexico discovered the remains of a pliosaur nicknamed as "Monster of Aramberri", which is also estimated at 15 m (49 ft) in length,[345] with shorter estimation about 11.5 m (38 ft).[346] This species is, however, claimed to be a juvenile and has been attacked by a larger pliosaur.[347] Some media sources claimed that Monster of Aramberri was a Liopleurodon but its species is unconfirmed thus far.[345] Another very large pliosaur was Pliosaurus macromerus, known from a single 2.8-metre-long (9.2 ft) incomplete mandible.[348] The Early Cretaceous Kronosaurus queenslandicus is estimated at 9–10.9 m (30–36 ft) in length and 10.6–12.1 t (11.7–13.3 short tons) in weight.[349][346] The Late Jurassic Megalneusaurus rex could reach lengths of 7.6–9.1 metres (25–30 ft).[350][351] Close contender in size was the Late Cretaceous Megacephalosaurus eulerti with a length in range of 6–9 m (20–30 ft).[352]

Proterosuchids (Proterosuchidae)

[edit]Proterosuchus fergusi is the largest known proterosuchid with a skull length of 47.7 cm (18.8 in) and a possible body length of 3.5–4 m (11–13 ft).[353]

Erythrosuchids (Erythrosuchidae)

[edit]

The largest erythrosuchid was Erythrosuchus africanus with a maximum length of 4.75–5 m (15.6–16.4 ft).[354]

Phytosaurs (Phytosauria)

[edit]Some of the largest known phytosaurs include Redondasaurus with a length of 6.4 m (21 ft)[355] and Smilosuchus with a length of more than 7 m (23 ft).[356]

Non-crocodylomorph pseudosuchians (Pseudosuchia)

[edit]

- The largest shuvosaurid and one of the largest pseudosuchian from the Triassic period was Sillosuchus. Biggest specimens could have reached 9–10 m (30–33 ft) in length.[357][358]

- The largest known carnivorous pseudosuchian of the Triassic is loricatan Fasolasuchus tenax, which measured an estimated of 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft).[357][358][359] It is both the largest "rauisuchian" known to science, and the largest non-dinosaurian terrestrial predator ever discovered.[citation needed] Biggest individuals of Postosuchus[360] and Saurosuchus[361] had a body length of around 7 m (23 ft). A specimen of Prestosuchus discovered in 2010 suggest that this animal also reached lengths of nearly 7 m (23 ft) making it one of the largest Triassic pseudosuchians.[362]

- Desmatosuchus was likely one of the largest known aetosaurs, about 4–6 m (13–20 ft) in length and 280 kg (620 lb) in weight.[363][364][365]

Crocodiles and close relatives (Crocodylomorpha)

[edit]

Aegyptosuchids (Aegyptosuchidae)

[edit]The Late Cretaceous Aegisuchus was originally estimated to reach 15 m (49 ft) in length by the lower estimate and as much as 22 m (72 ft) by the upper estimate although a length of over 15 m is likely a significant overestimate.[366] However, this estimation is likely to be a result of miscalculation, and its length would be only around 3.9 m (13 ft).[367]

Crocodylians (Crocodylia)

[edit]- The largest caiman and likely one of the largest crocodylians was Purussaurus brasiliensis estimated at 11–13 m (36–43 ft).[368] According to another information, maximum estimate measure 11.4 m (37 ft) and almost 7.8 t (8.6 short tons) in length and in weight respectively.[369] However, a 2022 study estimated a length of 7.6–9.2 metres (25–30 ft) and a mass of 2–6.2 metric tons (2.2–6.8 short tons) using a phylogenetic approach; and a length of 9.2–10 metres (30–33 ft) and mass of 3.9–4.9 metric tons (4.3–5.4 short tons) using a non-phylogenetic approach.[370]

- Another giant caiman was Mourasuchus. Various estimates suggest the biggest specimens reached 9.47 m (31.1 ft) in length and 8.5 t (9.4 short tons) in weight.[371] but more recent estimates suggest 4.7–5.98 m (15.4–19.6 ft) in body length.[370]

- The largest alligatoroid is likely Deinosuchus riograndensis at 12 m (39 ft) long and weighing 8.5 t (9.4 short tons).[372][373]

- The largest extinct species of the genus Alligator was the Haile alligator (Alligator hailensis), which had a skull 52.5 cm (20.7 in) long and was similar in size to the extant American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis).[374]

- The largest gavialids were Asian Rhamphosuchus at 8–11 m (26–36 ft)[375][376][369] and South American Gryposuchus at 10.15 m (33.3 ft) in length.[377][376]

- The basal crocodyloidean Astorgosuchus bugtiensis from the Oligocene was large. It estimated at 8 m (26 ft) in length.[376]

- The largest known true crocodile was Euthecodon which estimated to have reached 6.4–8.6 m (21–28 ft) or even 10 m (33 ft) long.[378][369] The largest species of the modern Crocodylus were Kenyan Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni at 7.56 m (24.8 ft) in length,[379][369] Tanzanian Crocodylus anthropophagus at 7.5 m (25 ft) in length[380][381] and indeterminate species from Kali Gedeh (Java) at 6–7 m (20–23 ft) in length.[382]

- The largest known mekosuchian is Paludirex vincenti, which is estimated to reach up to 5 m (16 ft).[383][384][310] Partial jaw specimen from Pliocene that is attributed to Quinkana suggest an individual about 6–7 m (20–23 ft) in length,[310] although other species (known from Oligocene to Pleistocene) are smaller with length around 1.5–3 m (4 ft 11 in – 9 ft 10 in).[385][386][387]

Paralligatorids (Paralligatoridae)

[edit]The largest paralligatorid was likely Kansajsuchus, estimated at up to 8 m (26 ft) long.[388]

Tethysuchians (Tethysuchia)

[edit]- Some extinct pholidosaurids reached giant sizes. In the past, Sarcosuchus imperator was believed to be the largest crocodylomorph, with initial estimates proposing a length of 12 m (39 ft) and a weight of 8 t (8.8 short tons).[389] However, recent estimates have now shrunk to a length of 9 to 9.5 m (29.5 to 31.2 ft) and a weight of 3.5 to 4.3 metric tons (3.9 to 4.7 short tons).[390] Related to Sarcosuchus, Chalawan thailandicus could have reached more than 10 m (33 ft) in length,[391] although other estimates suggest 7–8 m (23–26 ft).[376]

- The largest dyrosaurid was Phosphatosaurus gavialoides, estimated at 9 m (30 ft) in length.[392][376]

Stomatosuchids (Stomatosuchidae)

[edit]Stomatosuchus, a stomatosuchid, was estimated at 10 m (33 ft) in length.[393]

Notosuchians (Notosuchia)

[edit]- Some of largest terrestrial notosuchian crocodylomorphs were the Miocene sebecid Barinasuchus, with a skull of 95–110 cm (37–43 in) long, and Eocene sebecid Dentaneosuchus with estimated mandible length of 1 m (3.3 ft).[394][395] Various estimates suggest a possible length of these animals between 3–10 m (9.8–32.8 ft). Using proportion of Stratiotosuchus which is also large to have 47 cm (19 in) long skull,[396] Barinasuchus is estimated to have length at least 6.3 m (21 ft).[394][395]

- Other huge notosuchian, although only known from fragmentary material, is an early member Razanandrongobe, which skull size may exceeded that of Barinasuchus and overall length may be around 7 m (23 ft).[397][398]

Thalattosuchians (Thalattosuchia)

[edit]

- The largest thalattosuchian as well as the largest teleosauroid was unnamed fossil remain from Paja Formation, which may belongs to animal with length of 9.6 m (31 ft),[399] which is as large as outdated length estimate of the Early Cretaceous Machimosaurus rex, more recently estimated at 7.15 m (23.5 ft) in length.[400] Neosteneosaurus edwardsi (previously known as Steneosaurus edwardsi[401]) was the biggest Middle Jurassic crocodylomorph, it reached 6.6 m (22 ft) long.[400]

- Plesiosuchus was very large metriorhynchid. With the length of 6.83 m (22.4 ft) it exceeded even some pliosaurids of the same time and locality such as Liopleurodon.[402] Other huge metriorhynchids include Tyrannoneustes at 5 m (16 ft) in length[403] and Torvoneustes at 4.7 m (15 ft) in length.[404]

Basal crocodylomorphs

[edit]Redondavenator was the largest Triassic crocodylomorph ever recorded,[405] with a skull of at least 60 cm (2.0 ft) in length.[406][407] Another huge basal crocodylomorph was Carnufex[405] at 3 m (9.8 ft) long even through that is immature.[408]

Pterosaurs (Pterosauria)

[edit]

- The largest known pterosaur was Quetzalcoatlus northropi, at 127 kg (280 lb) and with a wingspan of 10–12 m (33–39 ft).[409] Another close contender is Hatzegopteryx, also with a wingspan of 12 m (39 ft) or more.[409] This estimate is based on a skull 3 m (9.8 ft) long.[410] Yet another possible contender for the title is Cryodrakon which had a 10-metre (33 ft) wingspan.[411] An unnamed pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Nemegt Formation could reach a wingspan of nearly 10 m (33 ft).[412][413] According to various assumptions, the wingspan of Arambourgiania philadelphiae reached from 8 m (26 ft) to more than 10 m (33 ft).[412][411] South American Tropeognathus reached the maximum wingspan of 8.7 m (29 ft).[414][415]

- The largest of non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs as well as the largest Jurassic pterosaur[416] was Dearc, with an estimated wingspan between 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) and 3.8 m (12 ft).[417] Only a fragmentary rhamphorhynchid specimen from Germany could be larger (184% the size of the biggest Rhamphorhynchus).[418] Other large non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs were Sericipterus, Campylognathoides and Harpactognathus, with the wingspan of 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in),[419] 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in),[419] and 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in),[418] respectively.

Choristoderes (Choristodera)

[edit]The largest known choristoderan, Kosmodraco dakotensis (previously known as Simoedosaurus dakotensis[420]) is estimated to have had a total length of around 5 m (16 ft).[421][420]

Tanystropheids (Tanystropheidae)

[edit]

Tanystropheus, the largest of all tanystropheids, reached up to 5 m (16 ft) in length.[422]

Thalattosaurs (Thalattosauria)

[edit]The largest species of thalattosaur, Miodentosaurus brevis grew to more than 4 m (13 ft) in length.[423] The second largest member of this group is Concavispina with a length of 3.64 m (11.9 ft).[424]

Ichthyosaurs (Ichthyosauria)

[edit]

- The largest known shastasaur, ichthyosaur and marine reptile was Ichthyotitan, which is estimated to have measured 25 m (82 ft). In addition to the Aust specimen, which has been attributed to Ichthyotitan, could’ve measured over 30 m (98 ft).[425] Another large shastasaur Shastasaurus sikanniensis at 21 m (69 ft) in length[426][427] and 81.5 t (180,000 lb) in weight.[428] Shonisaurus popularis was another large Ichthyosaur, measuring 15 m (49 ft) in length and weighing 29.7 t (65,000 lb).[427]

- The largest cymbospondylidae ichthyosaur as well as the largest animal of the Middle Triassic was Cymbospondylus youngorum at 17.65 m (57.9 ft) in length[428] and 44.7 t (99,000 lb) in weight.[428]

Pareiasaurs (Pareiasauria)

[edit]Largest pareiasaurs reached up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length. Such sizes had Middle Permian Bradysaurus, Embrithosaurus, and Nochelesaurus from South Africa,[429] and the Late Permian Scutosaurus from Russia.[429] The most robust Scutosaurus had 1.16 t (2,600 lb) in body mass.[429]

Captorhinids (Captorhinidae)

[edit]The heavy built Moradisaurus grandis, with a length of 2 m (6 ft 7 in),[430] is the largest known captorhinid.[431] The second largest captorhinid was Labidosaurikos with the largest adult skull specimen 28 cm (11 in) long.[432]

Non-avian dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

[edit]Sauropodomorphs (Sauropodomorpha)

[edit]The largest of non-sauropod sauropodomorphs ("prosauropod") was Euskelosaurus. It reached 12.2 m (40 ft) in length and 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight.[433] Another huge sauropodomorph Yunnanosaurus youngi reached 13 m (43 ft) long.[434]

Sauropods (Sauropoda)

[edit]

- A mega-sauropod, Maraapunisaurus fragillimus (previously known as Amphicoelias fragillimus), is a contender for the largest-known dinosaur in history. It has been estimated at 58–60 m (190–197 ft) in maximum length and 122,400 kg (269,800 lb) in weight.[435] Unfortunately, the fossil remains of this dinosaur have been lost.[435] More recently, it was estimated at 35–40 m (115–131 ft) in length and 80–120 t (180,000–260,000 lb) in weight.[436]

- Known from the incomplete and now disintegrated remains, the Late Cretaceous Bruhathkayosaurus matleyi was an anomalously large sauropod.[437] Informal estimations suggested as huge parameters as 45 m (148 ft) in length and 139–220 t (306,000–485,000 lb) in weight.[438] Some estimates, however, suggest 37 m (121 ft) and 95 t (209,000 lb) but it's still much heavier than most other sauropods.[438] More recent estimations by Gregory Paul in 2023 has placed its weight range around 110 t (240,000 lb) to a 170 t (370,000 lb). If true, it would make Bruhathkayosaurus the single largest terrestrial animal to have walked the earth and would have rivalled the largest blue whale recorded.[439]

- BYU 9024, a massive cervical vertebra found in Utah,[440] may belong to a Barosaurus lentus[441][442] or Supersaurus vivianae[443] of a huge size, possibly 45–48 m (148–157 ft) in length and 60–66 t (132,000–146,000 lb) in body mass.[441][444] Supersaurus vivianae itself may have been the longest dinosaur yet discovered as a study of 3 specimens suggested length of 39 m (128 ft) or over 40 m (130 ft).[443]

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum was likely the largest mamenchisaurid, reaching nearly 35 m (115 ft) in length and 60–80 t (130,000–180,000 lb) in weight.[436] Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis from the same family had 15 m (49 ft)-long neck, about 55% of its total length that could be at least 27 m (89 ft).[445]

- The Middle Jurassic Breviparopus taghbaloutensis was mentioned in The Guinness Book of Records as the longest dinosaur at 48 m (157 ft) although this animal is known only from fossil tracks.[446][447] Originally thought to be a brachiosaurid, it was later identified as a huge diplodocoid, possibly 33.5 m (110 ft) in length and 62 t (137,000 lb) in weight.[448]

- The tallest sauropod was Sauroposeidon proteles with estimated height at 16.5–18 m (54–59 ft).[449][450][451] Asiatosaurus could potentially reach 17.5 m (57 ft) in height, but this animal is known only from teeth.[449] Giraffatitan was estimated at 16 m (52 ft) in height.[452]

Other huge sauropods include Argentinosaurus, Alamosaurus, and Puertasaurus with estimated lengths of 30–33 m (98–108 ft) and weights of 50–80 t (55–88 short tons).[453] Patagotitan was estimated at 37 m (121 ft) in length[454] and 57 t (63 short tons) in average weight,[455] and was similar in size to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus.[456] Giant sauropods like Supersaurus, Sauroposeidon, and Diplodocus probably rivaled them in length but not in weight.[435] Dreadnoughtus was estimated at 49 t (108,000 lb) in weight[455] and 26 m (85 ft) in length, but the most complete individual was immature when it died.[457] Turiasaurus is considered the largest dinosaur from Europe,[458][459] with an estimated length of 30 m (98 ft) and a weight of 50 t (55 short tons).[453][459] However, lower estimates at 21 m (69 ft) and 30 t (66,000 lb) would make it smaller than the Portuguese Lusotitan, which reached 24 m (79 ft) in length and 34 t (75,000 lb) in weight.[460]

Many large sauropods are still unnamed and may rival the current record holders:

- The "Archbishop", a large brachiosaur that was discovered in 1930. As of October 2023[update], a scientific paper on the specimen is still in progress.[461]

- Brachiosaurus nougaredi is yet another large brachiosaur from Early Cretaceous North Africa. The remains have been lost, but the sacrum drawing remains. It suggests a sacrum of almost 1.3 m (4.3 ft) long,[462] making it the largest dinosaur sacrum discovered so far, except those of Argentinosaurus and Apatosaurus.[463]

- In 2010, the femur of a large sauropod was discovered in France. The femur suggests an animal that grew to immense sizes.[464]

Non-avian theropods (Theropoda)

[edit]

- The largest theropod as well as the largest terrestrial predator yet known is Tyrannosaurus rex, with the largest specimen known nicknamed Scotty (RSM P2523.8), located at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, is reported to measure 13 m (43 ft) in length. Using a mass estimation technique that extrapolates from the circumference of the femur, Scotty was estimated as the largest known specimen at 8.87 metric tons (9.78 short tons) in body mass[465]

- Other large theropods were Giganotosaurus carolinii, and Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, whose largest specimens known estimated at 13.2 m (43 ft)[466] and 12.3 m (40 ft)[467] in length, and weigh between 4.2 to 13.8 t (4.6 to 15.2 short tons)[468][469][470][471] and 14m (46 ft) in length and 7.4 metric tonnes (8.2 short tons) [472] respectively (which makes Spinosaurus the longest terrestrial carnivore). Some other notable giant theropods (e.g. Carcharodontosaurus, Acrocanthosaurus, and Mapusaurus) may also have rivaled them in size.

- Macroelongatoolithus, ranging from 34–61 cm (1.12–2.00 ft) in length,[473] is the largest known type of dinosaur egg.[474] It is assigned to oviraptorosaurs like Beibeilong.[474]

Armoured dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

[edit]The largest-known thyreophoran was Ankylosaurus at 9 m (30 ft) in length and 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons) in weight.[475][476] Stegosaurus was also 9 m (30 ft) long[459] but around 5 tonnes (5.5 short tons) tonnes in weight.[citation needed]

Marginocephalians (Marginocephalia)

[edit]Pachycephalosaurs (Pachycephalosauria)

[edit]The largest pachycephalosaur was the eponymous Pachycephalosaurus. Previously claimed to be at 7 m (23 ft) in length,[459] it was later estimated about 4.5 metres (14.8 ft) long and a weight of about 450 kilograms (990 lb).[477]

Ceratopsians (Ceratopsia)

[edit]

The largest ceratopsian known is Triceratops horridus, along with the closely related Eotriceratops xerinsularis both with estimated lengths of 9 m (30 ft). Pentaceratops and several other ceratopsians rival them in size.[478] Titanoceratops had one of the longest skull of any land animal, at 2.65 m (8.7 ft) long.[479] A recently discovered Torosaurus (nicknamed "Adam") may exceed this size with a skull length of 3 m (9.8 ft) meters.[480]

Ornithopods (Ornithopoda)

[edit]

- The very largest known ornithopods, like Shantungosaurus were as heavy as medium-sized sauropods at up to 23 t (25 short tons),[481][482] and 16.6 m (54 ft) in length.[481] Magnapaulia reached 12.5 m (41 ft) in length,[483] or, according to original description, even 15 m (49 ft).[484][459] The Mongolian Saurolophus, S. angustirostris, reached 13 m (43 ft) long and possibly more.[485] Such animal could weighed up to 11 t (12 short tons).[485] The largest Edmontosaurus reached 12 m (39 ft) in length and around 6 t (6.6 short tons) in body mass.[486] An estimated maximum length of Brachylophosaurus is 11 m (36 ft) resulting in weight of 7 t (7.7 short tons).[487] PASAC-1, informally named "Sabinosaurus", is the largest well-known North American saurolophine,[488] around 11 m (36 ft) long, that is about 20% larger than other known specimens.[489] Hypsibema missouriensis was up to 10.7 m (35 ft) long.[490][491] The Late Cretaceous Charonosaurus was estimated around 10 m (33 ft) in length and 5 t (5.5 short tons) in weight.[459][492]

- The largest ornithopod outside of Hadrosauroidea was likely the Iguanodon. Biggest specimens reached 11 m (36 ft) in length[493][494] and weighed around 4.5 t (5.0 short tons).[495] Another large ornithopod is Iguanacolossus, with 9 m (30 ft) in length and 5 t (5.5 short tons) in weight.[496][497]

- The largest rhabdodontid was Matheronodon, estimated at 4.8 m (16 ft) in length.[498] Rhabdodon reached approximately 4 m (13 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb) according to 2016 estimates.[499]

Birds (Aves)

[edit]

The largest bird in the fossil record may be the extinct elephant bird species Aepyornis maximus of Madagascar, whose closest living relative is the kiwi. Giant elephant birds exceeded 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) in height, and average a mass of 850 kg (1,870 lb)[500]

The largest fowl was the mihirung Dromornis stirtoni of Australia. It exceeded 2.7 m (8.9 ft) in height, and average a mass of 500 kilograms (1,100 lb)[501]

Another contender is Brontornis burmeisteri, an extinct flightless bird from South America which reached a weight of 319 kg (703 lb) and a height of approximately 2.8 metres (9.2 ft).[502]

The tallest recorded bird was Pachystruthio dmanisensis, a relative of the ostrich. This particular species of bird stood at 3.5 metres (11.5 ft) tall and average a mass of 450 kg (990 lb)[503]

The largest known flightless neoave was the terror bird Paraphysornis brasiliensis of South America, the Brazilian terror bird exceeded 240 kg (530 lb) in mass,[504]

Table of heaviest extinct bird species

[edit]Enantiornitheans (Enantiornithes)

[edit]One of the largest enantiornitheans was Enantiornis,[525] with a length in life of around 78.5 cm (30.9 in), hip height of 34 cm (13 in), weight of 6.75 kg (14.9 lb),[526] and wingspan comparable to some of the modern gulls, around 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in).[525] Gurilynia was the largest Mesozoic bird from Mongolia, with a length of 53 cm (21 in), hip height of 23.2 cm (9.1 in), and weight of 2.1 kg (4.6 lb).[526]

Avisauridae

[edit]The Late Cretaceous Avisaurus was almost as large as Enantiornis. It had a wingspan around 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in),[525] a book estimate weight of 5.1 kg (11 lb)[526] but a paper later estimated its weight up to 1.7 kilograms (3.7 lb) instead.[527]

Pengornithidae

[edit]One of the biggest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird was Pengornis at 50 cm (1.6 ft) in length[459] and skull length of 54.7 mm (2.15 in).[528]

Gargantuaviidae

[edit]Gargantuavis is the largest known bird of the Mesozoic, a size ranging between the cassowary and the ostrich, and a mass of 140 kg (310 lb) like modern ostriches.[529] In 2019 specimens MDE A-08 and IVPP-V12325 were measured at 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) in length, 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) in hip height, and 120 kg (260 lb) in weight.[511]

Dromornithiformes

[edit]

The largest dromornithid was Dromornis stirtoni over 3 m (9.8 ft) tall[530] and 528–584 kg (1,164–1,287 lb) in mass for males.[531]

Gastornid (Gastornithiformes)

[edit]Large individuals of Gastornis reached up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height.[532] Weight of Gastornis ranges from 100 kg (220 lb) to 156 kg (344 lb) and sometimes to 180 kg (400 lb) for European specimens and from 160 kg (350 lb) to 229 kg (505 lb) for North American.[533][509][534]

Waterfowl (Anseriformes)

[edit]

Possibly flightless, the Miocene Garganornis ballmanni was larger than any extant members of Anseriformes, with 15.3–22.3 kg (34–49 lb) in body mass.[535] Another huge anseriform was the flightless New Zealand goose (Cnemiornis). It reached 15–18 kg (33–40 lb), approaching in size to small species of moa.[536]

Swans (Cygnini)

[edit]The largest known swan was the Pleistocene giant swan (Cygnus falconeri), which reached a bill-to-tail length of about 190–210 cm (75–83 in),[537] a weight of around 16 kg (35 lb), and a wingspan of 3 m (9.8 ft).[520][538][539] The New Zealand swan (Cygnus sumnerensis) weighed up to 10 kg (22 lb), compared to the related extant black swan at only 6 kg (13 lb).[540] The large marine swan Annakacygna yoshiiensis from the Miocene of Japan far exceeded the extant mute swan in both size and weight.[541]

Anatinae

[edit]Finsch's duck (Chenonetta finschi) reached 1–2 kg (2.2–4.4 lb) in weight, surpassing related modern Australian wood duck (800 g (1.8 lb)).[542]

Pelicans, ibises and allies (Pelecaniformes)

[edit]- The Early Pliocene Pelecanus schreiberi was larger than most extant pelicans. Pelecanus odessanus from the Late Miocene was probably the same size as P. schreiberi, its tarsometatarsus is 150 mm (5.9 in) long.[543]

- The largest heron was the Bennu heron (Ardea bennuides).[dubious – discuss] Based on remains discovered, it was approximately 2 m (6.6 ft) tall and had a wingspan up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft), thus surpassing the size of the largest living species in the heron family, the goliath heron.[544]

- The Jamaican ibis (Xenicibis xympithecus) was a large ibis, weighing about 2 kg (70 oz).

Storks and allies (Ciconiiformes)

[edit]

The largest known of Ciconiiformes was Leptoptilos robustus, standing 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) tall and weighing an estimated 16 kg (35 lb).[545][521] Ciconia maltha is a relatively large species of Ciconia, with a height of over 5 feet (1.5 meters) and a wingspan up to 10 feet (3.0 meters) across.[546]

Cranes (Gruiformes)

[edit]A large true crane (Gruinae) from the late Miocene (Tortonian) of Germany was equal in size to the biggest extant cranes and resembled the long-beaked Siberian crane (Leucogeranus leucogeranus).[547]

Shorebirds (Charadriiformes)

[edit]Miomancalla howardi was the largest known charadriiform of all time, weighing approximately 0.6 kg (1.3 lb) more than the second-largest member, the great auk (Pinguinus impennis).[548]

Hesperornithines (Hesperornithes)

[edit]The largest known of the hesperornithines was Canadaga arctica at 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) long.[549]

New World vultures (Cathartiformes)

[edit]

One of the heaviest flying birds of all time was Argentavis, a Miocene teratornithid. The immense bird had a wingspan estimated up to 5.09–6.5 m (16.7–21.3 ft)[513][550] and a weight up to 70 to 72 kg (154 to 159 lb).[551][513] Argentavis's humerus was only slightly shorter than an entire human arm.[552] Another huge teratorn was Aiolornis, with a wingspan of around 5 m (16 ft).[553] The Pleistocene Teratornis merriami reached 13.7 kg (30 lb) and 2.94–3.38 m (9.6–11.1 ft) in wingspan, with lower size estimates still exceeding the largest specimens of California condor (Gymnogyps californianus).[554]

Seriemas and allies (Cariamiformes)

[edit]

The largest known-ever Cariamiforme and largest phorusrhacid or "terror bird" (highly predatory, flightless birds of America) was Brontornis, which was about 175 cm (69 in) tall at the shoulder, could raise its head 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) above the ground and could have weighed as much as 400 kg (880 lb).[555] The immense phorusrhacid Kelenken stood 3 m (9.8 ft) tall[556][557] with a skull 716 mm (28.2 in) long (460 mm (18 in) of which was beak), had the largest head of any known bird.[556] South American Phorusrhacos stood 2.4-2.7 m (7.9-8.8 ft) tall, and weighed nearly 130 kilograms (290 lb), as much as a male ostrich.[558][559] The largest North American phorusrhacid was Titanis, which reached a height of approximately 2.5 m (8.2 ft),[560] slightly taller than an African forest elephant.

Accipitriforms (Accipitriformes)

[edit]

The largest known bird of prey ever was the enormous Haast's eagle (Hieraaetus moorei), with a wingspan of 2.6 to 3 m (8 ft 6 in to 9 ft 10 in), relatively short for their size.[561][562] Total length was probably up to 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) in female[563] and they weighed about 10 to 15 kg (22 to 33 lb).[564] Another giant extinct hawk was Titanohierax about 7.3 kg (16 lb) that lived in the Antilles and The Bahamas, where it was among the top predators.[565] An unnamed late Quaternary eagle from Hispaniola could be 15–30% larger than the modern golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos).[566] Some extinct species of Buteogallus surpassed their extant relatives in size. Buteogallus borrasi was about 33% larger than the modern great black hawk (B. urubitinga).[567] B. daggetti, also known as "walking eagle", was around 40% larger than the savanna hawk (B. meridionalis).[568] Eyles's harrier (Circus eylesi) from the Pleistocene-Holocene of New Zealand was more than twice heavier than the extant C. approximans.[569]

Moa (Dinornithiformes)

[edit]The tallest known bird was the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus), part of the moa family of New Zealand that went extinct about 500 years ago. It stood up to 3.7 m (12 ft) tall,[570] and weighed approximately half as much as a large elephant bird due to its comparatively slender frame.[571]

Tinamous (Tinamiformes)

[edit]MPLK-03, a tinamou specimen that existed during the Late Pleistocene in Argentina, possibly belongs to the modern genus Eudromia and surpacces extant E. elegans and E. formosa in size by 2.2–8% and 6–14%, respectively.[572]

Elephant birds (Aepyornithiformes)

[edit]The largest bird in the fossil record may be the extinct elephant birds (Vorombe, Aepyornis) of Madagascar, which were related to the ostrich. They exceeded 3 m (9.8 ft) in height and 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) in weight.[571]

Ostriches (Struthioniformes)

[edit]With 450 kg (990 lb) in body mass, Pachystruthio dmanisensis from the lower Pleistocene of Crimea was the largest bird ever recorded in Europe. Despite its giant size, it was a good runner.[573] A possible specimen of Pachystruthio from the lower Pleistocene of Hebei Province (China) was about 300 kg (660 lb) in weight, twice heavier than the common ostrich (Struthio camelus).[574] Remains of the massive Asian ostrich (Struthio asiaticus) from the Pliocene[575] indicate a size 20% bigger than adult male of the extant Struthio camelus.[576]

Pigeons and doves (Columbiformes)

[edit]

The largest pigeon relative known was the dodo (Raphus cucullatus), possibly exceeding 1 m (3.3 ft) in height and weighing as much as 28 kg (62 lb), although recent estimates have indicated that an average wild dodo weighed much less at approximately 10.2 kg (22 lb).[577][578]

Pheasants, turkeys, gamebirds and allies (Galliformes)

[edit]The largest known of the Galliformes was likely the giant malleefowl, which could reach 7 kg (15 lb) in weight.[579]

Songbirds (Passeriformes)

[edit]The largest known songbird is the extinct giant grosbeak (Chloridops regiskongi) at 280 mm (11 in) long.[citation needed]

Cormorants and allies (Suliformes)

[edit]

- The largest known cormorant was the spectacled cormorant of the North Pacific (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus), which became extinct around 1850 and averaged around 6.4 kg (14 lb) and 1.15 m (3 ft 9 in).[524]

- The largest known darter was Giganhinga with estimated weight about 17.7 kg (39 lb),[519] earlier study even claims 25.7 kg (57 lb).[580]

- The largest known plotopterid, penguin-like flightless bird was Copepteryx titan that is known from 22 cm (8.7 in) long femur, almost twice as long as that of emperor penguin.[581]

Grebes (Podicipediformes)

[edit]The largest known grebe, the Atitlán grebe (Podylimbus gigas), reached a length of about 46–50 centimetres (18–20 in).[582]

Bony-toothed birds (Odontopterygiformes)

[edit]The largest known of the Odontopterygiformes— a group which has been variously allied with Procellariiformes, Pelecaniformes and Anseriformes and the largest flying birds of all time other than Argentavis were the huge Pelagornis, Cyphornis, Dasornis, Gigantornis and Osteodontornis.[citation needed] They had a wingspan of 5.5–6 m (18–20 ft) and stood about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) tall.[citation needed] Exact size estimates and judging which one was largest are not yet possible for these birds, as their bones were extremely thin-walled, light and fragile, and thus most are only known from very incomplete remains.[citation needed]

Woodpeckers and allies (Piciformes)