Lawrence Durrell

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 22 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 22 min

Lawrence Durrell | |

|---|---|

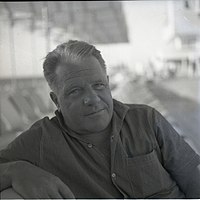

Durrell during his visit to Israel in 1962 | |

| Born | Lawrence George Durrell 27 February 1912 Jalandhar, Punjab, British India |

| Died | 7 November 1990 (aged 78) Sommières, France |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | British |

| Education | St Edmund's School, Canterbury |

| Period | 1931–1990 |

| Notable works | The Alexandria Quartet |

| Spouses | Nancy Isobel Myers

(m. 1935; div. 1947)Eve "Yvette" Cohen

(m. 1947; div. 1955)Claude-Marie Vincendon

(m. 1961; died 1967)Ghislaine de Boysson

(m. 1973; div. 1979) |

| Parents | |

| Relatives |

|

| Website | |

| lawrencedurrell | |

Lawrence George Durrell CBE (/ˈdʊrəl, ˈdʌr-/;[1] 27 February 1912[2] – 7 November 1990) was an expatriate British novelist, poet, dramatist, and travel writer. He was the eldest brother of naturalist and writer Gerald Durrell.

Born in India to British colonial parents, he was sent to England at the age of 11 for his education. He did not like formal education, but started writing poetry at the age of 15. His first book was published in 1935, when he was 23 years old. In March 1935 he and his mother and younger siblings moved to the island of Corfu. Durrell spent many years thereafter living around the world.

His most famous work is The Alexandria Quartet, published between 1957 and 1960. The best-known novel in the series is the first, Justine. Beginning in 1974, Durrell published The Avignon Quintet, using many of the same techniques. The first of these novels, Monsieur, or the Prince of Darkness, won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1974. The middle novel, Constance, or Solitary Practices, was nominated for the 1982 Booker Prize. In the 20th century, Durrell was a bestselling author and one of the most celebrated writers in England.[3]

Durrell supported his writing by working for many years in the Foreign Service of the British government. His sojourns in various places during and after World War II (such as his time in Alexandria, Egypt) inspired much of his work. He married four times, and had a daughter with each of his first two wives.

Early years in India and schooling in England

[edit]Durrell was born in Jalandhar, British India, the eldest son of Indian-born British colonials Louisa (who was Anglo-Irish) and Lawrence Samuel Durrell, an engineer of English ancestry.[3] His first school was St. Joseph's School, North Point, Darjeeling. He had three younger siblings — two brothers and a sister — naturalist Gerald Durrell, Leslie Durrell and author Margaret Durrell.

Like many other children of the British Raj, at the age of 11, Durrell was sent to England for schooling, where he briefly attended St. Olave's Grammar School before being sent to St. Edmund's School, Canterbury. His formal education was unsuccessful, and he failed his university entrance examinations. He began to write poetry seriously at the age of 15. His first collection, Quaint Fragments, was published in 1931, when he was 19 years old.

Durrell's father died of a brain haemorrhage in 1928, at the age of 43. His mother brought the family to England, and in 1932, she, Durrell, and his younger siblings settled in Bournemouth. There, he and his younger brother Gerald became friends with Alan G. Thomas, who had a bookstore and would become an antiquarian.[4] Durrell had a short spell working for an estate agent in Leytonstone (East London).[5]

Adult life and prose writings

[edit]First marriage and Durrell's move to Corfu

[edit]On 22 January 1935, Durrell married art student Nancy Isobel Myers (1912–1983), with whom he briefly ran a photographic studio in London.[6] It was the first of his four marriages.[7] Durrell was always unhappy in England, and in March of that year he persuaded his new wife, and his mother and younger siblings, to move to the Greek island of Corfu. There they could live more economically and escape both the English weather, and what Durrell considered the stultifying English culture, which he described as "the English death".[8]

That same year Durrell's first novel, Pied Piper of Lovers, was published by Cassell. Around this time he chanced upon a copy of Henry Miller's 1934 novel Tropic of Cancer.[9] After reading it, he wrote to Miller, expressing intense admiration for his novel. Durrell's letter sparked an enduring friendship[9] and mutually critical relationship that spanned 45 years. Durrell's next novel, Panic Spring, was strongly influenced by Miller's work,[10] while his 1938 novel The Black Book abounded with "four-letter words... grotesques,... [and] its mood equally as apocalyptic" as Tropic.[10]

In Corfu, Lawrence and Nancy lived together in bohemian style. For the first few months, the couple lived with the rest of the Durrell family in the Villa Anemoyanni at Kontokali. In early 1936, Durrell and Nancy moved to the White House, a fisherman's cottage on the shore of Corfu's northeastern coast at Kalami, then a tiny fishing village. The Durrell family's friend Theodore Stephanides, a Greek doctor, scientist and poet, was a frequent guest, and Miller stayed at the White House in 1939.

Durrell fictionalised this period of his sojourn on Corfu in the lyrical novel Prospero's Cell. His younger brother Gerald Durrell, who became a naturalist, published his own version in his memoir My Family and Other Animals (1954) and in the following two books of Gerald's so-called Corfu Trilogy, published in 1969 and 1978. Gerald describes Lawrence as living permanently with his mother and siblings — his wife Nancy is not mentioned at all. Lawrence, in his turn, refers only briefly to his brother Leslie, and he does not mention that his mother and two other siblings were also living on Corfu in those years. The accounts cover a few of the same topics; for example, both Gerald and Lawrence describe the roles played in their lives by the Corfiot taxi driver Spyros Halikiopoulos and Theodore Stephanides. In Corfu, Lawrence became friends with Marie Aspioti, with whom he cooperated in the publication of Lear's Corfu.[11]: 260

Pre WW2: In Paris with Miller and Nin

[edit]In August 1937, Lawrence and Nancy travelled to the Villa Seurat in Paris, France, to meet Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. Together with Alfred Perles, Nin, Miller, and Durrell "began a collaboration aimed at founding their own literary movement. Their projects included The Shame of the Morning and the Booster, a country club house organ that the Villa Seurat group appropriated "for their own artistic ... ends."[12] They also started the Villa Seurat Series in order to publish Durrell's Black Book, Miller's Max and the White Phagocytes, and Nin's Winter of Artifice. Jack Kahane of the Obelisk Press served as publisher.

Durrell said that he had three literary uncles: T. S. Eliot, the Greek poet George Seferis, and Miller. He first read Miller after finding a copy of Tropic of Cancer that had been left behind in a public lavatory. He said the book shook him "from stem to stern".[9]

Durrell's first novel of note, The Black Book: An Agon, was strongly influenced by Miller; it was published in Paris in 1938. The mildly pornographic work was not published in Great Britain until 1973. In the story, the main character Lawrence Lucifer struggles to escape the spiritual sterility of dying England and finds Greece to be a warm and fertile environment.

World War Two

[edit]Breakdown of marriage

[edit]At the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, Durrell's mother and siblings returned to England, while Nancy and he remained on Corfu. In 1940, they had a daughter, Penelope Berengaria. After the fall of Greece, Lawrence and Nancy escaped from Kalamata, where they had been teaching,[13] via Crete to Alexandria, Egypt. The marriage was already under strain and they separated in 1942. Nancy took the baby Penelope with her to Jerusalem.

During his years on Corfu, Durrell had made notes for a book about the island. He did not write it fully until he was in Egypt towards the end of the war. In the book Prospero's Cell, Durrell described Corfu as "this brilliant little speck of an island in the Ionian".[page needed] with waters "like the heartbeat of the world itself".[14]

Press attaché in Egypt and Rhodes; second marriage

[edit]During World War Two, Durrell served as a press attaché to the British embassies, first in Cairo and then Alexandria. While in Alexandria he met Eve (Yvette) Cohen (1918–2004), a Jewish Alexandrian. She inspired his character Justine in The Alexandria Quartet. In 1947, after his divorce from Nancy was completed, Durrell married Eve Cohen, with whom he had been living since 1942.[15] The couple's daughter, Sappho Jane, was born in Oxfordshire in 1951,[16] and named after the ancient Greek poet Sappho.[17]

In May 1945, Durrell obtained a posting to Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands that Italy had taken over from the disintegrating Ottoman Empire in 1912 during the Balkan Wars. With the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943, German forces took over most of the islands and held onto them as besieged fortresses until the war's end. Mainland Greece was at that time locked in civil war. A temporary British military government was established in the Dodecanese at war's end, pending sovereignty being transferred to Greece in 1947, as part of war reparations from Italy. Durrell set up house with Eve in the little gatekeeper's lodge of an old Turkish cemetery, just across the road from the building used by the British Administration. (Today this is the Casino in Rhodes' new town.) His co-habitation with Eve Cohen could be discreetly ignored by his employer, while the couple gained from staying within the perimeter security zone of the main building. His book Reflections on a Marine Venus was inspired by this period and was a lyrical celebration of the island. It avoids more than a passing mention of the troubled war times.

British Council work in Córdoba and Belgrade; teaching in Cyprus

[edit]In 1947, Durrell was appointed director of the British Council Institute in Córdoba, Argentina. He served there for eighteen months, giving lectures on cultural topics.[18] He returned to London with Eve in the summer of 1948, around the time that Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia broke ties with Stalin's Cominform. Durrell was posted by the British Council to Belgrade, Yugoslavia,[19] and served there until 1952. This sojourn gave him material for his novel White Eagles over Serbia (1957).

In 1952, Eve had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalised in England. Durrell moved to Cyprus with their daughter Sappho Jane, buying a house and taking a position teaching English literature at the Pancyprian Gymnasium to support his writing. He next worked in public relations for the British government during the local agitation for union with Greece. He wrote about his time in Cyprus in Bitter Lemons, which won the Duff Cooper Prize in 1957. In 1954, he was selected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Durrell left Cyprus in August 1956. Political agitation on the island and his British government position resulted in his becoming a target for assassination attempts.[11]: 27

Justine and The Alexandria Quartet

[edit]In 1957, Durrell published Justine, the first novel of what was to become his most famous work, The Alexandria Quartet. Justine, Balthazar (1958), Mountolive (1958), and Clea (1960), deal with events before and during the Second World War in the Egyptian city of Alexandria. The first three books tell essentially the same story and series of events, but from the varying perspectives of different characters. Durrell described this technique in his introductory note in Balthazar as "relativistic". Only in the final novel, Clea, does the story advance in time and reach a conclusion. Critics praised the Quartet for its richness of style, the variety and vividness of its characters, its movement between the personal and the political, and its locations in and around the ancient Egyptian city which Durrell portrays as the chief protagonist: "The city which used us as its flora—precipitated in us conflicts which were hers and which we mistook for our own: beloved Alexandria!" The Times Literary Supplement review of the Quartet stated: "If ever a work bore an instantly recognizable signature on every sentence, this is it."

In 2012, when the Nobel Records were opened after 50 years, it was revealed that Durrell had been nominated for the 1961 Nobel Prize in Literature, but did not make the final list.[20] In 1962, however, he did receive serious consideration, along with Robert Graves, Jean Anouilh, and Karen Blixen, but ultimately lost to John Steinbeck.[21] The Academy decided that "Durrell was not to be given preference this year"—probably because "they did not think that The Alexandria Quartet was enough, so they decided to keep him under observation for the future." However, he was never nominated again.[21] They also noted that he "gives a dubious aftertaste … because of [his] monomaniacal preoccupation with erotic complications."[21]

Two further marriages and settling in Languedoc

[edit]In 1955 Durrell separated from Eve Cohen. He married again in 1961, to Claude-Marie Vincendon, whom he met on Cyprus. She was a Jewish woman born in Alexandria. Durrell was devastated when Claude-Marie died of cancer in 1967. He married for the fourth and last time in 1973, to Ghislaine de Boysson, a French woman. They divorced in 1979.

In the spring of 1960, Durrell was hired to rewrite the script for the 1963 film Cleopatra.[22] The production company had also proposed a film of Justine which would eventually appear in 1969.

Durrell settled in Sommières, a small village in Languedoc, France, where he purchased a large house on the edge of the village. The house was situated in extensive grounds surrounded by a wall. Here he wrote The Revolt of Aphrodite, comprising Tunc (1968) and Nunquam (1970). He also completed The Avignon Quintet, published from 1974 to 1985, which used many of the same motifs and styles found in his metafictional Alexandria Quartet. Although the related works are frequently described as a quintet, Durrell referred to it as a "quincunx".

The opening novel, Monsieur, or the Prince of Darkness, received the 1974 James Tait Black Memorial Prize. That year, Durrell was living in the United States and serving as the Andrew Mellon Visiting Professor of Humanities at the California Institute of Technology.[23] The middle novel of the quincunx, Constance, or Solitary Practices (1981), which portrays France in the 1940s under the German occupation, was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1982.

Other works from this period are Sicilian Carousel, a non-fiction celebration of that island, The Greek Islands, and Caesar's Vast Ghost, which is set in and chiefly about the region of Provence, France.

Later years, literary influences, attitudes and reputation

[edit]A longtime smoker, Durrell suffered from emphysema for many years. He died of a stroke at his house in Sommières in November 1990, and was buried in the churchyard of the Chapelle St-Julien de Montredon in Sommières.

He was predeceased by his younger daughter, Sappho Jane, who took her own life in 1985 at the age of 33. After Durrell's death, it emerged that Sappho's diaries included allusions to an alleged incestuous relationship with her father.[17][24][25][26]

Durrell's government service and his attitudes

[edit]Durrell worked for several years in the service of the Foreign Office. He was senior press officer to the British embassies in Athens and Cairo, press attaché in Alexandria and Belgrade, and director of the British Institutes in Kalamata, Greece, and Córdoba, Argentina. He was also director of Public Relations in the Dodecanese Islands and on Cyprus. He later refused an honour as a Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, because he felt his "conservative, reactionary and right-wing" political views might be a cause for embarrassment.[11]: 185 Durrell's works of humour, Esprit de Corps and Stiff Upper Lip, are about life in the diplomatic corps, particularly in Serbia. He claimed to have disliked both Egypt and Argentina,[27] although not nearly so much as he disliked Yugoslavia.

Durrell's poetry

[edit]Durrell's poetry has been overshadowed by his novels, but Peter Porter, in his introduction to a Selected Poems, calls Durrell "One of the best [poets] of the past hundred years. And one of the most enjoyable."[28] Porter describes Durrell's poetry: "Always beautiful as sound and syntax. Its innovation lies in its refusal to be more high-minded than the things it records, together with its handling of the whole lexicon of language."[29]

British citizenship

[edit]For much of his life, Durrell resisted being identified solely as British, or as only affiliated with Britain. He preferred to be considered cosmopolitan. Since his death, there have been claims that Durrell never had British citizenship, but he was originally classified as a British citizen as he was born to British colonial parents living in India under the British Raj.[citation needed]

In 1966 Durrell and many other former and present British residents became classified as non-patrial, as a result of an amendment to the Commonwealth Immigrants Act.[3] The law was covertly intended to reduce migration from India, Pakistan, and the West Indies, but Durrell was also penalized by it and refused citizenship. He had not been told that he needed to "register as a British citizen in 1962 under the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962".[3]

As The Guardian reported in 2002, Durrell in 1966 was "one of the best selling, most celebrated English novelists of the late 20th century" and "at the height of his fame".[3] Denied the normal citizenship right to enter or settle in Britain, Durrell had to apply for a visa for each entry. Diplomats were outraged and embarrassed at these events. "Sir Patrick Reilly, the ambassador in Paris, was so incensed that he wrote to his Foreign Office superiors: 'I venture to suggest it might be wise to ensure that ministers, both in the Foreign Office and the Home Office, are aware that one of our greatest living writers in the English language is being debarred from the citizenship of the United Kingdom to which he is entitled.'"[3]

Legacy

[edit]After Durrell's death, his lifelong friend Alan G. Thomas donated a collection of books and periodicals associated with Durrell to the British Library. This is maintained as the distinct Lawrence Durrell Collection. Thomas had earlier edited an anthology of writings, letters and poetry by Durrell, published as Spirit of Place (1969). It contained material related to Durrell's own published works. An important documentary resource is kept by the Bibliothèque Lawrence Durrell at Paris Nanterre University.[citation needed]

Bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Pied Piper of Lovers (1935)

- Panic Spring, under the pseudonym Charles Norden (1937)

- The Black Book (1938; republished in Great Britain in 1973 by Faber and Faber)

- Cefalu (1947; republished as The Dark Labyrinth in 1958)

- White Eagles Over Serbia (1957)

- The Alexandria Quartet (1962)

- Justine (1957)

- Balthazar (1958)

- Mountolive (1958)

- Clea (1960)

- The Revolt of Aphrodite (1974)

- The Avignon Quintet (1992)

- Monsieur: or, The Prince of Darkness (1974)

- Livia: or, Buried Alive (1978)

- Constance: or, Solitary Practices (1982)

- Sebastian: or, Ruling Passions (1983)

- Quinx: or, The Ripper's Tale (1985)

- Judith (2012, written 1962-c. 1966)

Travel

[edit]- Prospero's Cell: A guide to the landscape and manners of the island of Corcyra [Corfu] (1945; republished 2000) (ISBN 0-571-20165-2)

- Reflections on a Marine Venus (1953)

- Bitter Lemons (1957; republished as Bitter Lemons of Cyprus 2001)

- Blue Thirst (1975)

- Sicilian Carousel (1977)

- The Greek Islands (1978)

- Caesar's Vast Ghost: Aspects of Provence (1990)

Poetry

[edit]- Quaint Fragments: Poems Written between the Ages of Sixteen and Nineteen (1931)

- Ten Poems (1932)

- Transition: Poems (1934)

- A Private Country (1943)

- Cities, Plains and People (1946)

- On Seeming to Presume (1948)

- The Tree of Idleness and Other Poems (1955)

- Collected Poems (1960)

- The Poetry of Lawrence Durrell (1962)

- Selected Poems: 1935–1963. Edited by Alan Ross (1964)

- The Ikons (1966)

- The Suchness of the Old Boy (1972)

- Collected Poems: 1931–1974. Edited by James A. Brigham (1980)

- Selected Poems of Lawrence Durrell. Edited by Peter Porter (2006)

Drama

[edit]- Bromo Bombastes, under the pseudonym Gaffer Peeslake (1933)

- Sappho: A Play in Verse (1950)

- An Irish Faustus: A Morality in Nine Scenes (1963)

- Acte (1964)

Humour

[edit]- Esprit de Corps, Sketches from Diplomatic Life (1957)

- Stiff Upper Lip, Life Among the Diplomats (1958)

- Sauve Qui Peut (1966)

- Antrobus Complete (1985), brings together the three preceding volumes plus the previously uncollected sketch "Smoke, the embassy cat" (1978); omits "A smircher besmirched", which appeared in the U.S. but not the British edition of Stiff Upper Lip

Letters and essays

[edit]- A Key to Modern British Poetry (1952)

- Art & Outrage: A Correspondence About Henry Miller Between Alfred Perles and Lawrence Durrell (1959)

- Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller: A Private Correspondence (1963), edited by George Wickes

- Spirit of Place: Letters and Essays on Travel (1969), edited by Alan G. Thomas

- Literary Lifelines: The Richard Aldington—Lawrence Durrell Correspondence (1981), edited by Ian S. MacNiven and Harry T. Moore

- A Smile in the Mind's Eye (1980)

- "Letters to T. S. Eliot" (1987), Twentieth Century Literature Vol. 33, No. 3 pp. 348–358.

- The Durrell-Miller Letters: 1935–80 (1988), edited by Ian S. MacNiven

- Letters to Jean Fanchette (1988), edited by Jean Fanchette

- From the Elephant's Back: Collected Essays & Travel Writings (2015), edited by James Gifford

Editing and translating

[edit]- Six Poems From the Greek of Sikelianós and Seféris (1946), translated by Durrell

- The King of Asine and Other Poems (1948), by George Seferis and translated by Durrell, Bernard Spencer, and Nanos Valaoritis

- The Curious History of Pope Joan (1954; revised 1960), originally "The Papess Joanne" by Emmanuel Roídes and translated by Durrell

- The Best of Henry Miller (1960), edited by Durrell

- New Poems 1963: A P.E.N. Anthology of Contemporary Poetry (1963), edited by Durrell

- Wordsworth; Selected by Lawrence Durrell (1973), edited by Durrell

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Durrell". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Biography". International Lawrence Durrell Society. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Ezard, John (29 April 2002). "Durrell Fell Foul of Migrant Law". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- ^ Botting, Douglas (1999). Gerald Durrell: The Authorised Biography. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255660-X.

- ^ Hodgkin, Joanna (2013). Amateurs in Eden: the story of a bohemian marriage; Nancy and Lawrence Durrell. London: Virago. ISBN 9781844087945.

- ^ Haag, Michael (2006). "Only the City is Real: Lawrence Durrell's Journey to Alexandria". Alif. 26: 39–47.

- ^ MacNiven, Ian S. (1998). Lawrence Durrell: A Biography. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-17248-2. p. xiii.

- ^ Anna Lillios, "Lawrence Durrell", in Magill's Survey of World Literature, volume 7, pp. 2334–2342; Salem Press, Inc., 1995

- ^ a b c Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Durrell, Lawrence (31 March 2014). "Lawrence Durrell speaking at UCLA 1/12/1972". YouTube. From the archives of the UCLA Communications Studies Department. Digitized 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b Karl Orend, "New Bibles", Times Literary Supplement 22 August 2008 p 15

- ^ a b c Lillios, Anna (2004). Lawrence Durrell and the Greek World. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-1575910765. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Dearborn, Mary V. (1992). The Happiest Man Alive: A Biography of Henry Miller. Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-671-77982-6. p. 192 and picture insert captions.

- ^ Durrell was the director of the British Council’s English Language Institute in Kalamata (Peloponnese) from September 1940 to April 1941. The little house provided for him on Navarinou Street (no. 83), on the seafront, remains. With his first wife Nancy (née Myers) and baby daughter Penelope, the family fled to Egypt as the German army advanced (see, e.g., Ian MacNiven (1998), Lawrence Durrell: a biography, Faber, pp.226-7; Nikos Zervis (1999), Lawrence Durrell in Kalamata, isbn: 978-960-90690-1-0 (published privately) (in Greek); Joanna Hodgkin (2023), Amateurs in Eden: the story of a bohemian marriage; Nancy and Lawrence Durrell, Virago, pp.258-63.

- ^ Durrell, Lawrence (1978). Prospero's cell : a guide to the landscape and manners of the island of Corcyra. Penguin Books. p. 100. ISBN 0140046852.

- ^ "Journals and Letters [of] Sappho Durrell". Sappho Durrell, quoted posthumously in a lengthy review of an "edited selection from the journals and letters [of Sappho Durrell] ... drawn mainly from 1979". Granta 37. 1 October 1991. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ a b Jay Rayner (14 September 1991). "Inside Story: Daddy Dearest - The writer Lawrence Durrell cast a long, dark shadow over the short and troubled life of his daughter, Sappho". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 October 2020 – via Google Groups.

- ^ Interview with Marc Alyn, published in Paris in 1972, translated by Francine Barker in 1974; reprinted in Earl G. Ingersoll, Lawrence Durrell: Conversations, Associated University Presses, 1998. ISBN 0-8386-3723-X. p. 138.

- ^ Alyn, op. cit. Ingersoll, p. 139.

- ^ J. D. Mersault, "The Prince Returns: In Defense of Lawrence Durrell", The American Reader, n.d.; accessed 14 October 2016

- ^ a b c Alison Flood (3 January 2013). "Swedish Academy reopens controversy surrounding Steinbeck's Nobel prize". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Bernstein, Matthew (2000) [1994]. Walter Wanger, Hollywood Independent. University of Minnesota Press. p. 355. ISBN 0-8166-3548-X.

- ^ Andrews, Deborah. (ed)., ed. (1991). The Annual Obituary 1990. Gale. p. 678.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (14 August 1991). "A Daughter's Intimations". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "A man pursued by furies (a review of Bowker's biography)". The Herald. 14 December 1996. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Redwine, Bruce. Tales of Incest: The Agony of Saph and Pa Durrell. www.academia.edu.

- ^ José Ruiz Mas (2003). Lawrence Durrell in Cyprus: A Philhellene against Enosis (Report). Epos. p. 230. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.

- ^ Porter, Peter, ed. (2006). Lawrence Durrell: Selected Poems. Faber and Faber.

- ^ Porter 2006, p. xxi

Further reading

[edit]Biography and interviews

- Andrewski, Gene; Mitchell, Julian (1960). "Lawrence Durrell, The Art of Fiction No. 23". The Paris Review (Autumn–Winter 1959–1960). Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Bowker, Gordon. Through the Dark Labyrinth: A Biography of Lawrence Durrell. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997.

- Chamberlin, Brewster. A Chronology of the Life and Times of Lawrence Durrell. Corfu: Durrell School of Corfu, 2007.

- Commengé, Béatrice. Une vie de paysages. Paris: Verdier, 2016.

- Durrell, Lawrence. The Big Supposer: An Interview with Marc Alyn. New York: Grove Press, 1974.

- Haag, Michael. Alexandria: City of Memory. London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. [Intertwined biographies of Lawrence Durrell, E. M. Forster and Constantine Cavafy in Alexandria.]

- Haag, Michael. Vintage Alexandria: Photographs of the City 1860–1960. Cairo and New York: The American University of Cairo Press, 2008. [Includes an introduction on the historical, social and literary significance of Alexandria, and extensively captioned photographs of the cosmopolitan city and its inhabitants, including Durrell and people he knew.]

- MacNiven, Ian. Lawrence Durrell—A Biography. London: Faber and Faber, 1998.

- Todd, Daniel Ray. An Annotated, Enumerative Bibliography of the Criticism of Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet and his Travel Works. New Orleans: Tulane U, 1984. [Doctoral dissertation]

- Ingersoll, Earl. Lawrence Durrell: Conversations. Cranbury: Ashgate; 1998.

Critical Studies

- Alexandre-Garner, Corinne, ed. Lawrence Durrell Revisited : Lawrence Durrell Revisité. Confluences 21. Nanterre: Université Paris X, 2002.

- Alexandre-Garner, Corinne, ed. Lawrence Durrell: Actes Du Colloque Pour L'Inauguration De La Bibliothèque Durrell. Confluences 15. Nanterre: Université Paris-X, 1998.

- Alexandre-Garner, Corinne. Le Quatuor D'Alexandrie, Fragmentation Et Écriture : Étude Sur Lámour, La Femme Et L'Écriture Dans Le Roman De Lawrence Durrell. Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature 136. New York: Peter Lang, 1985.

- Begnal, Michael H., ed. On Miracle Ground: Essays on the Fiction of Lawrence Durrell. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1990.

- Clawson, James M. Durrell Re-read : Crossing the Liminal in Lawrence Durrell's Major Novels. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2016.

- Cornu, Marie-Renée. La Dynamique Du Quatuor D'Alexandrie De Lawrence Durrell: Trois Études. Montréal: Didier, 1979.

- Fraser, G. S. Lawrence Durrell: A Study. London: Faber and Faber, 1968.

- Friedman, Alan Warren, ed. Critical Essays on Lawrence Durrell. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

- Friedman, Alan Warren. Lawrence Durrell and "The Alexandria Quartet": Art for Love's Sake. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

- Gifford, James. Personal Modernisms: Anarchist Networks and the Later Avant-Gardes . EdmontonL University Alberta Press, 2014.

- Herbrechter, Stefan. Lawrence Durrell, Postmodernism and the Ethics of Alterity. Postmodern Studies 26. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999.

- Hoops, Wiklef. Die Antinomie Von Theorie Und Praxis in Lawrence Durrells Alexandria Quartet: Eine Strukturuntersuchung. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1976.

- Isernhagen, Hartwig. Sensation, Vision and Imagination: The Problem of Unity in Lawrence Durrell's Novels. Bamberg: Bamberger Fotodruck, 1969.

- Kaczvinsky, Donald P. Lawrence Durrell's Major Novels, or The Kingdom of the Imagination. Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 1997.

- Kaczvinsky, Donald P., ed. Durrell and the City: Collected Essays on Place. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2011.

- Keller-Privat, Isabelle. « Between the lines »: l’écriture du déchirement dans la poésie de Lawrence Durrell. Paris: Presses Universitaires de Paris Ouest, 2015.

- Lampert, Gunther. Symbolik Und Leitmotivik in Lawrence Durrells Alexandria Quartet. Bamberg: Rodenbusch, 1974.

- Lillios, Anna, ed. Lawrence Durrell and the Greek World. London: Associated University Presses, 2004.

- Moore, Harry T., ed. The World of Lawrence Durrell. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1962.

- Morrison, Ray. A Smile in His Mind's Eye: A Study of the Early Works of Lawrence Durrell. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005.

- Pelletier, Jacques. Le Quatour D'Alexandrie De Lawrence Durrell. Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet. Paris: Hachette, 1975.

- Pine, Richard. Lawrence Durrell: The Mindscape. Corfu: Durrell School of Corfu, revised edition, 2005.

- Pine, Richard. The Dandy and the Herald: Manners, Mind and Morals From Brummell to Durrell. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988.

- Raper, Julius Rowan, et al, eds. Lawrence Durrell: Comprehending the Whole. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995.

- Rashidi, Linda Stump. (Re)constructing Reality: Complexity in Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet. New York: Peter Lang, 2005.

- Ruprecht, Walter Hermann. Durrells Alexandria Quartet: Struktur Als Belzugssystem. Sichtung Und Analyse. Swiss Studies in English 72. Berne: Francke Verlag, 1972.

- Sajavaara, Kari. Imagery in Lawrence Durrell's Prose. Mémoires De La Société Néophilologique De Helsinki 35. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1975.

- Sertoli, Giuseppe. Lawrence Durrell. Civilta Letteraria Del Novecento: Sezione Inglese—Americana 6. Milano: Mursia, 1967.

- Potter, Robert A., and Brooke Whiting. Lawrence Durrell: A Checklist. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles Library, 1961.

- Thomas, Alan G., and James Brigham. Lawrence Durrell: An Illustrated Checklist. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983.

Critical articles

- Zahlan, Anne R. "Always Friday the Thirteenth: The Knights Templar and the Instability of History in Durrell's The Avignon Quintet". Deus Loci: The Lawrence Durrell Journal NS11 (2008–09): 23–39.

- Zahlan, Anne R. "Avignon Preserved: Conquest and Liberation in Lawrence Durrell's Constance". The Literatures of War. Ed. Richard Pine and Eve Patten. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. 253–276.

- Zahlan, Anne R. "City as Carnival: Narrative as Palimpsest: Lawrence Durrell's The Alexandria Quartet". The Journal of Narrative Technique 18 (1988): 34–46.

- Zahlan, Anne R. "Crossing the Border: Lawrence Durrell's Alexandrian Conversion to Post-Modernism". South Atlantic Review 64:4 (Fall 1999).

- Zahlan, Anne R. "The Destruction of the Imperial Self in Lawrence Durrell's The Alexandria Quartet". Self and Other: Perspectives on Contemporary Literature XII. University Press of Kentucky, 1986. 3–12.

- Zahlan, Anne R. "The Most Offending Souls Alive: Ruskin, Mountolive, and the Myth of Empire". Deus Loci: The Lawrence Durrell Journal NS10 (2006).

- Zahlan, Anne. R. "The Negro as Icon: Transformation and the Black Body" in Lawrence Durrell's The Avignon Quintet. South Atlantic Review 71.1 (Winter 2006). 74–88.

- Zahlan, Anne. R. "War at the Heart of the Quincunx: Resistance and Collaboration in Durrell's Constance". Deus Loci: The Lawrence Durrell Journal NS12 (2010). 38–59.

External links

[edit]- The International Lawrence Durrell Society A non-profit educational organization promoting the works and study of Lawrence Durrell

- Durrell 2012: The Lawrence Durrell Centenary Centenary event website

- Durrell Celebration in Alexandria

- Petri Liukkonen. "Lawrence Durrell". Books and Writers.

- Lawrence Durrell at IMDb

- Lawrence Durrell discography at Discogs

Articles

- Andrewski, Gene; Mitchell, Julian (23 April 1959). "Lawrence Durrell: The Art of Fiction No. 23 (interview)". The Paris Review. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- Gifford, James (30 July 2004). "Lawrence Durrell: Text, Hypertext, Intertext". Agora: An Online Graduate Journal. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Gifford, James (30 November 2001). "Forgetting A Homeless Colonial: Gender, Religion and Transnational Childhood in Lawrence Durrell's Pied Piper of Lovers". Jouvert: A Journal of Postcolonial Studies. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- "Lawrence Durrell in the ambiguous white metropolis": an essay on the Alexandria Quartet, The Times Literary Supplement (TLS), 27 August 2008.

KSF

KSF