Lillian Randolph

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

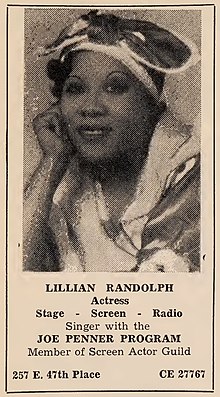

Lillian Randolph | |

|---|---|

Randolph in 1952 | |

| Born | Castello Randolph December 14, 1898[1] Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | September 12, 1980 (aged 81) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1931–1980 |

| Spouse(s) | Jack Chase Edward Sanders

(m. 1951; div. 1953)? McKee[a] |

| Children | 2, including Barbara Randolph |

| Relatives | Amanda Randolph (sister) |

Lillian Randolph (December 14, 1898 – September 12, 1980) was an American actress and singer, a veteran of radio, film, and television. She worked in entertainment from the 1930s until shortly before her death. She appeared in hundreds of radio shows, motion pictures, short subjects, and television shows.

Randolph is most recognized for appearing in It's a Wonderful Life (1946), Magic (1978), and her final onscreen project, The Onion Field (1979). She prominently contributed her voice to the character Mammy Two Shoes in nineteen Tom and Jerry cartoons released between 1940 and 1952.

Early life and education

[edit]

Randolph was born Castello Randolph in Knoxville, Tennessee, the daughter of a Methodist minister and a teacher.[3][4][5] She was the younger sister of actress Amanda Randolph.[b][8][9]

Career

[edit]Radio

[edit]Randolph began her professional career singing on local radio in Cleveland and Detroit.[4][8] At WXYZ in Detroit,[10] she was noticed by George W. Trendle, station owner and developer of The Lone Ranger. He got her into radio training courses, which paid off in roles for local radio shows. Randolph was tutored by a white actor for three months on racial dialect prior to obtaining any radio roles.[11]

In 1936, she moved on to Los Angeles to work on Al Jolson's radio show,[12] on Big Town, on the Al Pearce show,[13] and to sing at the Club Alabam[14] there.[4][8][15]

Actress

[edit]Randolph and her sister Amanda were continually looking for roles to make ends meet. In 1938, she opened her home to Lena Horne, who was in California for her first movie role in The Duke Is Tops (1938); the film was so tightly budgeted, Horne had no money for a hotel.[16]

Randolph opened her home during World War II with weekly dinners and entertainment for service people in the Los Angeles area through American Women's Voluntary Services.[17][18]

Randolph played the role of the maid Birdie Lee Coggins in The Great Gildersleeve, a radio comedy and subsequent films,[19] and as Madame Queen on the Amos 'n' Andy radio show and television show from 1937 to 1953.[19][20] She was cast in the Gildersleeve job on the basis of her wonderful laugh.[21] Upon hearing the Gildersleeve program was beginning, Randolph made a dash to NBC. She tore down the halls; when she opened the door for the program, she fell on her face. Randolph was not hurt and she laughed, which got her the job.[8] She also portrayed Birdie in the television version of The Great Gildersleeve.[22]

In 1955, Lillian was asked to perform the Gospel song, "Were You There" on the television version of the Gildersleeve show. The positive response from viewers resulted in a Gospel album by Randolph on Dootone Records.[23][24][25] She found the time for the role of Mrs. Watson on The Baby Snooks Show and Daisy on The Billie Burke Show.[26][27]

Her best known film roles were those of Annie in It's a Wonderful Life (1946) and Bessie in The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947).[28][29]

The West Adams district of Los Angeles was once home to lawyers and tycoons, but during the 1930s, many residents were either forced to sell their homes or take in boarders because of the economic times. The bulk of the residents who were earlier members of the entertainment community had already moved to places such as Beverly Hills and Hollywood. In the 1940s, members of the African-American entertainment community discovered the charms of the district and began purchasing homes there, giving the area the nickname "Sugar Hill". Hattie McDaniel was one of the first African-American residents. In an attempt to discourage African-Americans from making their homes in the area, some residents resorted to adding covenants to the contracts when their homes were sold, either restricting African-Americans from purchasing them or prohibiting them from occupying the houses after purchase.[30] Lillian and her husband, boxer Jack Chase,[31] were victims of this type of discrimination.[32]

In 1946, the couple purchased a home on West Adams Boulevard with a restrictive covenant that barred them from moving into it.[33] The US Supreme Court declared the practice unconstitutional in 1948.[30] After divorcing Chase, Randolph married railroad dining car server Edward Sanders, in August 1951.[3] The couple divorced in December 1953.[34]

Like her sister, Amanda, Lillian was also one of the actresses to play the part of Beulah on radio. Randolph assumed the role in 1952 when Hattie McDaniel became ill; that same year, she received an "Angel" award from the Caballeros, an African-American businessmen's association, for her work in radio and television for 1951.[35] She played Beulah until 1953, when Amanda took over for her.[36]

In 1954, Randolph had her own daily radio show in Hollywood, where those involved in acting were featured.[37] In the same year, she became the first African American on the board of directors for the Hollywood chapter of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.[38]

In William Hanna and Joseph Barbera's Tom and Jerry cartoons at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio during the 1940s and early 1950s, she was uncredited for voicing the maid character, Mammy Two Shoes. The character's last appearance in the cartoons was in Push-Button Kitty in September 1952. MGM, Hanna-Barbera and Randolph had been under fire from the NAACP, which called the role a stereotype. Activists had been complaining about the maid character since 1949. The character was written out entirely. Many of these had a white actress (June Foray) redubbing the character in American TV broadcasts and in the DVD collections.[39]

This was not the only time Randolph received criticism. In 1946, Ebony published a story critical of her role of Birdie on The Great Gildersleeve radio show. Randolph and Sam Moore, a scriptwriter on the program, provided a rebuttal to them in the magazine.[4][40] Lillian Randolph believed these roles were not harmful to the image or opportunities of African-Americans. Her reasoning was that the roles themselves would not be discontinued, but the ethnicity of those in them would change.[41]

In 1956, Randolph and her choir, along with fellow Amos 'n' Andy television show cast members Tim Moore, Alvin Childress, and Spencer Williams set off on a tour of the US as "The TV Stars of Amos 'n' Andy". However, CBS claimed it was an infringement of its rights to the show and its characters. The tour soon came to an end.[42]

By 1958, Lillian, who started out as a blues singer, returned to music with a nightclub act.[43]

Randolph was selected to play Bill Cosby's character's mother in his 1969 television series, The Bill Cosby Show.[8] She later appeared in several featured roles on Sanford and Son and The Jeffersons in the 1970s. She also taught acting, singing and public speaking.[44]

Randolph made a guest appearance on a 1972 episode of the sitcom Sanford and Son, entitled "Here Comes the Bride, There Goes the Bride" as Aunt Hazel, an in-law of the Fred Sanford (Redd Foxx) character who humorously gets a cake thrown in her face, after which Fred replies "Hazel, you never looked sweeter!".[45] Her Amos 'n' Andy co-star, Alvin Childress, also had a role in this episode.[46][47] She played Mabel in Jacqueline Susann's Once Is Not Enough (1975) and also appeared in the television miniseries, Roots (1977),[48] Magic (1978) and The Onion Field (1979).[49]

In March 1980, she was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame.[50]

Randolph's daughter, Barbara, grew up watching her mother perform. At age eight, Barbara had already made her debut in Bright Road (1953) with Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge.[51]

Choosing to adopt her mother's maiden name, Barbara Randolph appeared in her mother's nightclub acts, including with Steve Gibson and the Red Caps, and had a role in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner in 1967.[52][53] She decided to follow a singing career.[54][55][56]

Death

[edit]Randolph died of cancer at Arcadia Methodist Hospital in Arcadia, California on September 12, 1980.[57][58][59] She is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills). Her sister, Amanda, is buried beside her.[5]

Partial filmography

[edit]- Life Goes On (1938)[60] – Cinthy

- The Duke Is Tops (1938) – Woman with Sciatica (uncredited)

- The Toy Wife (1938) – Black Nun with Rose (uncredited)

- Streets of New York (1939) – Judge's Maid (uncredited)

- Way Down South (1939) – Slave (uncredited)

- The Marx Brothers at the Circus (1939) – Black Woman - 'Swingali' (uncredited)

- Am I Guilty? (1940) – Mrs. Jones

- Barnyard Follies (1940) – Birdie (uncredited)

- Little Men (1940) – Asia

- One Big Mistake (1940), a featurette starring Dewey "Pigmeat" Markham

- Tom and Jerry (1940-1952) – Mammy Two Shoes

- West Point Widow (1941) – Sophie

- Kiss the Boys Goodbye (1941) – Bethany Plantation Chorus Servant (uncredited)

- Gentleman from Dixie (1941) – Aunt Eppie

- Birth of the Blues (1941) – Dancing Woman (uncredited)

- All-American Co-Ed (1941) – Deborah, the Washwoman

- Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost (1942) – Hyacinth

- Hi, Neighbor (1942) – Birdie

- The Palm Beach Story (1942) – Maid on Train (uncredited)

- The Glass Key (1942) – Basement Club Entertainer (uncredited)

- The Great Gildersleeve (1942) – Birdie Lee Calkins

- No Time for Love (1943) – Hilda (uncredited)

- Happy Go Lucky (1943) – Tessie (uncredited)

- Hoosier Holiday (1943) – Birdie

- Gildersleeve on Broadway (1943) – Birdie

- Phantom Lady (1944) – Woman at Train Platform (uncredited)

- Up in Arms (1944) – Black Woman in Cable Car (uncredited)

- The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944) – Black Woman (uncredited)

- Gildersleeve's Ghost (1944) – Birdie, Gildersleeve's Housekeeper

- Three Little Sisters (1944) – Mabel

- A Song for Miss Julie (1945) – Eliza Henry

- Riverboat Rhythm (1946) – Azalea (uncredited)

- Child of Divorce (1946) – Carrie, the Maid

- It's a Wonderful Life (1946) – Annie

- The Hucksters (1947) – Violet (voice, uncredited)

- The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947) – Bessie

- Sleep, My Love (1948) – Parkhurst's Maid (uncredited)

- Let's Live a Little (1948) – Sarah (uncredited)

- Once More, My Darling (1949) – Mamie

- Dear Brat (1951) – Dora

- That's My Boy (1951) – May, Maid

- Bend of the River (1952) – Aunt Tildy (uncredited)

- Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) – Cleaning Woman

- The Great White Hope (1970) – Housekeeper (uncredited)

- How to Seduce a Woman (1974) – Matilda

- Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins (1975) – Elderly Woman Driver

- The Wild McCullochs (1975) – Missy

- Jacqueline Susann's Once Is Not Enough (1975) – Mabel

- The World Through the Eyes of Children (1975) – Susan

- Jennifer (1978) – Martha

- Magic (1978) – Sadie

- The Onion Field (1979) – Nana, Jimmy's Grandmother (final film role)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bob McCann, Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television, 2022, p. 277

- ^ Ellenberger, Alan R. (2001). Celebrities in Los Angeles Cemeteries: A Directory. McFarland. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-7864-0983-9.

- ^ a b Radio Actress Lillian Randolph Seeks Divorce. Jet. March 5, 1953. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Lillian Randolph". BlackPast.org. December 29, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. (2 volume set). McFarland. p. 613. ISBN 978-1476625997. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Five Red Caps". Singers.com. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ New York Beat. Jet. December 31, 1953. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Witbeck, Charles (September 1, 1969). "Madame Queen Joins Cosby". The Evening Independent. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ Rea, E. B. (January 10, 1948). "Does Radio Give Our Performers a Square Deal?". The Afro American. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Billy Mitchell Now On The Air". The Afro American. August 22, 1931. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Barlow, William, ed. (1998). Voice over: the making of Black radio. Temple University Press. p. 334. ISBN 1566396670.

- ^ "Copy of promotional material for Al Jolson's radio show". museumoffamilyhistory.com. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Jovien, Harold (April 2, 1940). "Via Your Dial". The Afro American. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ "Club Alabam". Eighth & Wall. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ Steinhauser, Si (May 24, 1942). "Girls Can't Qualify For Announcing Jobs, Says Network Leader". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Bogle, Donald, ed. (2006). Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams: The Story of Black Hollywood. One World/Ballantine. p. 432. ISBN 0345454197. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Network and Local Radio Listings". The Sunday Sun. January 4, 1942. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Rea, E.B. (March 16, 1943). "Encores and Echoes". Baltimore Afro-American. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Fanning, Will (April 23, 1958). "A Color Peacock To Shore Show; Notes". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ BCL (October 1, 1945). "Riding the Airwaves". Milwaukee Journal.

- ^ Shaffer, Rosalind (December 23, 1945). "Canny Judgment Boosted 'The Great Gildersleeve'". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Forecast. Jet. April 29, 1954. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Theatrical Whirl". The Afro American. March 3, 1956. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Theatrical Whirl". The Afro American. April 7, 1956. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Edwards, Dave, Callahan, Mike, Eyries, Patrice. "Dootone/Dooto Album Discography". BSN Pubs.com. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Newcomers With Snooks". The Milwaukee Journal (magazine section). September 15, 1946. p. 12.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "Lillian Randolph, a film and television jewel". African-American Registry. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ McCann, Bob, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. McFarland. p. 461. ISBN 978-0786437900. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ a b "West Adams History". westadamsheightssugarhill.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Springs, Toledo. "Chasing Jack Chase: Part 5 – Fade to Black". thesweetscience.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Lillian Randolph and husband Jack Chase". Los Angeles Public Library. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ "Actress Fights Home Covenants". Baltimore Afro-American. September 14, 1946. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Actress Lillian Randolph Divorces Mate. Jet. December 17, 1953. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ "Lillian Randolph". Baltimore Afro-American. May 17, 1952. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Lillian Randolph Sets Busy Pace On Radio. Jet. April 10, 1952. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ People. Jet. October 28, 1954. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Entertainment. Jet. April 15, 1954. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Lehman, Christopher P., ed. (2009). The Colored Cartoon. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1558497795. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Letters and Pictures To The Editor". Ebony. April 1946.

- ^ MacDonald, J. Fred. "Don't Touch That Dial!: radio programming in American life, 1920–1960". jfredmacdonald.com. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ Clayton, Edward T. (October 1961). The Tragedy of Amos 'n' Andy. Ebony. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ New York Beat. Jet. May 1, 1958. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Kisner, Ronald E., ed. (April 6, 1978). Marla Gibbs: TV Maid for The Jeffersons. Jet. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Sarasota Herald-Tribune TV Week". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. May 5, 1972. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Television. Jet. January 27, 1972. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Alvin Childress on Sanford and Son". Washington Afro-American. May 25, 1976. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ Lucas, Bob, ed. (January 27, 1977). Roots Of Blacks Shown In Eight Days Of TV Drama. Jet. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Deaths Elsewhere". Toledo Blade. September 15, 1980. Retrieved September 20, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Black Film Hall of Fame Inducts 7. Jet. March 20, 1980. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Like Mother, Like Daughter. Jet. September 25, 1952. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Louie, ed. (May 23, 1968). Film Boost For Star's Daughter. Jet. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Lillian and Barbara Randolph at Allen's Tin Pan Alley". The Spokesman-Review. July 29, 1958. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Barbara Randolph Seeks Record Stardom. Jet. December 29, 1960. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Barbara Randolph". IMDb. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ Goldberg, Marv. "Marv Goldberg's R & B Notebook – Back to the Red Caps". Goldberg, Marv. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Lillian Randolph, 65; Movie and TV Actress". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 17, 1980. p. D 27. ProQuest 121111763. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "People and Places". Star-News. September 16, 1980. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ Census. Jet. October 9, 1980. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ McCann, Bob (December 21, 2009). Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. McFarland. ISBN 9780786458042.

External links

[edit]- Lillian Randolph at IMDb

- Lillian Randolph at the TCM Movie Database

- Lillian Randolph at Find a Grave

- Lillian Randolph Movies & TV New York Times

- Lillian Randolph-early 1940s-photo Eighth & Wall

- Index of radio shows Lillian Randolph performed in Archived January 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine David Goldin

Watch

[edit]- Amos 'n' Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy Video by Hulu

- The Great Gildersleeve TV Episode at Internet Archive.

Listen

[edit]- The Beulah Show at Internet Archive – 1953.

- The Great Gildersleeve Radio Episodes at Internet Archive.

KSF

KSF