List of U.S. state reptiles

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

Twenty-eight U.S. states have named an official state reptile. As with other state symbols, states compare admirable aspects of the reptile and of the state, within designating statutes. Schoolchildren often start campaigns promoting their favorite reptile to encourage state legislators to enact it as a state symbol. Many secretaries of state maintain educational web pages that describe the state reptile.

Oklahoma was the first state to name an official reptile, the common collared lizard, in 1969. Only two states followed in the 1970s, but the ensuing decades saw nominations at a rate of almost one per year. State birds are more common, with all 50 states naming one, and they were adopted earlier, with the first one selected in 1927.

Before their formal designation as state reptiles, Florida's alligator, Maryland's terrapin, and Texas's horned lizard were all mascots of a major in-state university. West Virginia's timber rattlesnake was an early American flag element dating back to 1775.

Because of their cold-blooded nature, reptiles are more common in warmer climates, and 19 of the 28 state reptiles represent southern states. Six states chose a species named after the state. A turtle was chosen by more than half of the states. In all, the most frequently chosen species, with four states naming it, is the painted turtle. One state reptile, the bog turtle, is Critically endangered. The Alabama red-bellied turtle is legally designated as an endangered species in the United States, and several others, also turtles, are threatened at some lesser level.

State reptiles

[edit]Governmental aspects

[edit]Legislation

[edit]

A reptile becomes the official state symbol after it is voted in by the state legislature. Although many states require the bill to be signed by the governor, in some the enabling act is a resolution (legislature vote only). In 2004, Illinois held a popular vote to pick the painted turtle, but legislation was still required in 2005 to make the choice official.[20]

Schoolchildren often start the campaigns for state reptiles.[59] Three of the four states choosing the painted turtle credit school classes with initiating the process.[10][29][53] The process may require students to be knowledgeable of their selection, as was the case in Florida when students advocated for the loggerhead sea turtle; "Working with State Representative Curtis Richardson (D-Tallahassee), the students provided information and answered questions regarding the symbols."[60] In New York, students statewide voted to pick one of four turtles; the common snapping turtle edged the painted turtle 5,048 to 5,005. Assemblyman Joel Miller had sponsored the turtle election to interest students in politics and said of the results, "as with every election, every vote is important".[61]

Candidate state reptiles are not assured of making it through the legislative process. In Minnesota, 1998 and 1999 bills proposing the Blanding's turtle were unsuccessful.[62] In Pennsylvania in 2009, the House passed an eastern box turtle bill which died in the Senate without a vote.[63] Virginia proponents of the eastern box turtle have seen 1999 and 2009 bids fail. For the most recent attempt, a legislative opponent of the turtle said it was too cowardly for the state because of its defensive shell, and suggested the rattlesnake would be a better representative. The turtle also drew scorn for often perishing on roads, but its most serious problem was a too-close association with bordering state, North Carolina.[64][65]

Justification

[edit]"Whereas, the painted turtle is a hard worker and can withstand cold temperatures like the citizens of Vermont, and

Whereas, the colors of the painted turtle represent the beauty of our state in autumn, and

Whereas, the painted turtle is one of the most common turtles in Vermont, and

Whereas, the painted turtle adds to the diversity of Vermont's habitat..."

Like other state symbols, a state reptile is intended to show state pride. The designation has no economic or wildlife protection effect.[59][66] States justify their choice of state reptiles, with differing rationales, in designating legislation and on websites:

- North Carolina selected the eastern box turtle because its behavior reflects admirable human ideals: "The turtle watches undisturbed as countless generations of faster 'hares' run by to quick oblivion, and is thus a model of patience for mankind, and a symbol of our State's unrelenting pursuit of great and lofty goals."[67]

- Maryland notes its historical associations with the diamondback terrapin: "Chesapeake colonists ate terrapin prepared Native-American fashion, roasted whole in live coals. Abundant and easy to catch, terrapin were so ample that landowners often fed their slaves and indentured servants a staple diet of terrapin meat. Later, in the 19th century, the turtle was appreciated as gourmet food, especially in a stew laced with cream and sherry."[68]

- Ohio touts the ubiquity and practical benefits of its reptile: "The black racer snake was adopted because it is native to all 88 Ohio counties and is called the 'farmer's friend' because it eats disease-carrying rodents."[69]

- Texas stresses the conservation needs of the Texas horned lizard: "It is perhaps most appropriate for designation as an official state symbol because, like many other things truly Texan, it is a threatened species."[70]

Use

[edit]The state reptile concept serves education. Some states offer lesson plans using the reptile for teachers to introduce children to the legislative process, discuss state geography, or develop state patriotism.[71][72][73] Many Secretaries of State have a "kids page" describing the reptile.[74][75][76] Some, such as Missouri's Robin Carnahan, tout state-provided coloring books.[77]

Rate of adoption and comparison to other symbols

[edit]

In 1969, Oklahoma designated the first state reptile when it chose the common collared lizard or "mountain boomer".[42][66] Two states followed suit in the 1970s, seven states in the 1980s, eight states in the 1990s, and eight states in the 2000s.[nb 1] As of March 2019, twenty-eight of the fifty states have named a state reptile; Utah and New Jersey both adopted an official state repitile in the 2010s.[51][33]

In contrast to state reptiles, state birds have been more rapidly adopted, with the first state designating one in 1927 and the fiftieth in 1973.[78] As of January 2011, other types of animals more popular for state symbolization were mammals (46),[79] fish (45),[80] and insects (42).[81] Animal symbols less popular than reptiles were butterflies (17),[81] amphibians (17),[82] dogs (11),[83] dinosaurs (5),[84] bats (3),[85] and crustaceans (3).[86][87][88]

In their almanac of U.S. state symbols, Benjamin and Barbara Shearer spend comparatively little text on state reptiles. They spend a full chapter each on state birds, trees and flowers; within those chapters, they take about a half page to describe the campaign to establish each state's specific symbol.[89] Reptiles, on the other hand, are shown only in list format in a chapter titled "Miscellaneous", where the other non-bird animals (and many non-animals) are listed. Shearer and Shearer consider the state reptiles to be part of a "last thirty years" phenomenon (written in 2003) that includes such particular items as a state's "official beverage".[90]

Geography

[edit]

Perhaps owing to the greater presence of cold-blooded (ectothermic) reptiles in warmer climates,[91] the states in the southern half of the United States have more commonly designated a state reptile. From the twenty-four of the contiguous states roughly south of the Mason–Dixon line,[nb 2] only four lack a state reptile. From east to west, they are Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and Arkansas.[90][nb 3]

In contrast, in the north half of the central and western states, only one, Wyoming, has named a state reptile.[57] In the Great Lakes region, there is a cluster of three states (Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio) that named a reptile.[20][29][40] In the Northeast, there is another cluster of three participating states (Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont).[27][36][53]

Neither of the noncontiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii, have named a state reptile.[90] The District of Columbia lacks a state reptile although it does have an official tree, flower, bird,[92] fish,[93] amphipod,[94] and bat,[95] and an amphibian is under consideration.[96] None of the organized territories of the United States have state reptiles, although all four have designated official flowers.[97][98][99][100]

Six states chose reptiles named after the state. In common names, Arizona and Texas were represented by the Arizona ridge-nosed rattlesnake and Texas horned lizard.[2][4][47] Mississippi and North Carolina appeared in scientific names: Alligator mississippiensis and Terrapene carolina carolina.[30][38] Alabama and New Mexico appeared in both common names (Alabama red-bellied turtle and New Mexico whiptail lizard) and scientific names (Pseudemys alabamensis and Cnemidophorus neomexicanus).[1][2][34]

Previous symbology

[edit]Politics

[edit]Although there is no official reptile of the United States, some of the state reptiles have had previous appearances in American politics. In particular, the timber rattlesnake (West Virginia) has had close association with American independence.

A United States flag with a timber rattlesnake predates the stars and stripes flag. In 1775, Christopher Gadsden developed an emblem with a coiled rattlesnake with the words "Don't tread on me" on a yellow background. Versions of the Gadsden flag were used by the Continental Navy's first commodore, early Marines, and minutemen and regular army units in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.[101]

The timber rattlesnake is also famous for appearing on the First Navy Jack, a red and white striped flag. However, although traditionally believed to have been used by the Continental Navy, recent scholarship asserts that the snake on that jack was a late 19th-century invention. Nevertheless, in 1975, the U.S. Navy brought back the traditional (snake-showing) jack for the service's bicentennial. After 1980, the oldest commissioned vessel in the U.S. Navy was designated to use the traditional jack. Since 2002, in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. Navy has all its ships using the First Navy Jack.[102]

| Gadsden Flag | First Navy Jack |

|---|---|

|

|

West Virginia named the timber rattlesnake as its state reptile in 2008.[55] A 2009 article, "West Virginia's state reptile", in the state wildlife magazine drew a connection to the older American rattlesnake symbol:

Actually, the warning on the early flags was not meant to depict the timber rattlesnake as being ferocious or the American people as being warlike. The true message was that the citizens of the Colonies were a peaceable and freedom-loving people, but if England's King George III continued with his oppressive policies toward the Colonies, then they would respond with great wrath. This response would be much like that of a timber rattlesnake, which is peaceable and slow to anger, but will attack aggressively when provoked and will not stop fighting until the enemy retreats.

Benjamin Franklin, writing as an anonymous person, submitted the following statement concerning the disposition of the timber rattlesnake to the Pennsylvania Journal in 1775: "She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage...she never wounds ‘till she has generously given notice, even to her enemy, and cautioned him against the danger of treading on her."[103]

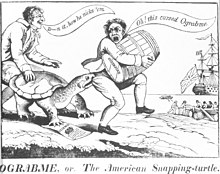

In contrast to the positive symbology of the rattlesnake, some political use has been for criticism. The snapping turtle (New York) was the central feature of a famous American political cartoon. Published in 1808 in Federalist protest of the Jeffersonian Embargo Act of 1807, the cartoon showed a snapping turtle, jaws locked fiercely to the rear of an American trader, who was attempting to carry a barrel of goods onto a British ship. The trader was seen whimsically uttering the words "Oh! this cursed Ograbme" (the backwards spelling of "embargo").[104][105] Also, during the Great Depression, the gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise) was known as the "Hoover chicken" (a sarcastic reference to President Herbert Hoover) because it was eaten by poor people out of work.[106][107]

Athletics

[edit]

Three states chose reptiles that were already prominently associated with a major university in the state:

- Florida honored the American alligator in 1987, but the Gators have titled the University of Florida's teams since 1911. In that year, a printer made a spur-of-the-moment decision to print an alligator emblem on a shipment of the schools football pennants; the mascot stuck, perhaps because the team captain's nickname was Gator.[108]

- Maryland honored the diamondback terrapin in 1994, but the mascot of Maryland's main state university in College Park has been the Terrapins or "Terps" since 1932. In that year, the football coach, who had encountered the animal as a boy near the Chesapeake Bay, proposed it as a mascot to oppose the Wildcats, Tigers, and such of enemy teams.[109][nb 4]

- Texas honored the Texas horned lizard in 1993, but private Texas Christian University has had the associated mascot the Horned Frog since 1896. According to legend, the football team identified with the lizards found on the practice field as the athletes and reptiles were similarly scrappy. The college founder's son, Addison Clark Jr., a faculty member and the initiator of the football team, had been fascinated by the creatures. By 1897, the lizard appeared as a logo on the front of the school yearbook, which Clark had also started and was managing.[110]

Biology

[edit]

In terms of common divisions of reptiles, turtles are most popular. Fifteen of the twenty-seven states give them official status.[nb 1][nb 5] The rest of the state reptiles comprise four snakes,[nb 6] five lizards,[nb 7] and three crocodilians.[nb 8][nb 9] Eighteen states name a reptile at the species level,[nb 10] two a genus,[nb 11] and seven a subspecies.[nb 12]

The species most frequently adopted as a state reptile is the painted turtle, with four states designating it: Colorado (the western subspecies), Illinois, Michigan, and Vermont.[10][20][29][53] Three southern states—Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi—represent themselves with the American alligator.[12][24][30] A species of box turtle, Terrapene carolina or common box turtle, has been chosen by three states, with North Carolina and Tennessee using the Terrapene carolina carolina (eastern box turtle) subspecies,[38][46] and with Missouri using the Terrapene carolina triungus (three-toed box turtle) subspecies.[31] Two bordering western states, California and Nevada, chose the desert tortoise.[6][24] The loggerhead sea turtle was named by South Carolina as state reptile, while Florida chose it as state saltwater reptile.[nb 13][14][45] Florida also named an official tortoise, the gopher tortoise, the same animal as Georgia's state reptile.[12][16][17]

Four genera are represented with different species in the list. Terrapene (box turtles) has Terrapene ornata (Kansas) along with Terrapene carolina (Missouri, North Carolina, and Tennessee).[21][31][38][46] Under Gopherus (gopher tortoises), there are Gopherus polyphemus (Georgia's state reptile and Florida's state tortoise) and Gopherus agassizii (California and Nevada).[6][19][24] Under Crotalus (one of two rattlesnake genera),[111] Arizona named Crotalus willardi willardi, while West Virginia chose Crotalus horridus.[2][4][55] With Phrynosoma (horned lizards), Wyoming specified the entire genus, but Texas specified Phrynosoma cornutum.[47][57]

Conservation

[edit]General reptile declines and state reptile examples

[edit]| 1953 Golden Guide | 2001 Golden Guide |

|---|---|

| "As a group [reptiles] are neither 'good' nor 'bad', but are interesting and unusual, although of minor importance. If they should all disappear it would not make much difference one way or the other."[112] | "Reptiles and amphibians are an important part of the environment...They help control harmful pests and are prey for other creatures. Needless killing...must stop. Wild areas...should be preserved."[113] |

Writing in 1988, naturalist J. Whitfield Gibbons asserted that awareness of the conservation needs of reptiles had lagged that of large mammals and game species.[114] However, comparison of different editions of the Golden Guide does show increasing sensitivity to U.S. reptile conservation over the last half of the 20th century.

In their 2000 review article "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians", Gibbons and colleagues argue that while the general public is more sympathetic to amphibians (perhaps because of their soft skin), reptile species are actually more endangered. Although populations can decline from natural causes, and it is difficult to prove the exact reason for a specific reptile's decline, human actions are behind most of the species' problems. Gibbons et al. describe six causes of reptile reductions, incidentally furnishing several examples of state reptile species impacted.[115]

- Overharvesting. Overcollection by humans has strongly hurt many reptile species, especially turtles.[116] The diamondback turtle (Maryland), once extremely common, dropped sharply in the beginning of the 20th century because of its popularity in soup but is gradually recovering now that harvesting for food has mostly stopped.[115][117][118] Capture for the pet trade has been strongly implicated in the decline of box turtles (Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee).[119] The timber rattlesnake (West Virginia) is threatened by "rattlesnake roundups" because females take nine years to mature and only produce four young per year.[120] However, not all reptile usage is unsustainable. Since the late 20th century recovery of the American alligator (Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi), its numbers have been successfully managed by game restrictions and commercial ranching.[115][121][122]

- Habitat loss. Gopher tortoises (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise) have been impacted by the loss of 97% of the Southeast's longleaf pine forest.[115][123]

- Introduced invasive species. New plant species have harmed the desert tortoise (California, Nevada) and gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's official tortoise).[124][125] Egg-eating fire ants have reduced the Texas horned lizard (Texas) from part of its range.[115][126]

- Environmental pollution. Water pollution is primarily seen in turtles and crocodilians and can affect their eggs and sex characteristics.[115] Male American alligators (Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi) have been found with lowered testosterone and altered gonads in a chemically contaminated lake.[115][127]

- Disease. Increased disease in wild populations often follows weakening from other environmental stressors, such as habitat loss.[115] Upper lung infection and shell diseases have been implicated in the decline of the desert tortoise (California, Nevada) and gopher tortoise (Georgia, Florida's state tortoise).[115][128][129][130]

- Climate change represents a future threat by changing habitat. Reptiles are more unsafe than birds because they have less ability to move large distances.[131] Gibbons and colleagues do not describe any examples of impact on specific state reptile species, although they mention a general concern for turtles and crocodilians having their populations become imbalanced—the animals sexes are determined by temperature of the eggs.[115]

IUCN ratings

[edit]

In keeping with the general issues of reptiles, some of the U.S. state reptiles are dwindling species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains a system of ratings, going from Extinct to Least Concern. None of the U.S. state reptiles are in the most extreme categories of Extinct, Extinct in the Wild, or Critically Endangered. Two species are IUCN Endangered: the Alabama red-bellied turtle (Alabama) and the loggerhead sea turtle (South Carolina, also the state saltwater reptile of Florida).[3][15] However, in the United States, only the Alabama red-bellied turtle is legally an endangered species.[132] The loggerhead sea turtle is only considered "threatened" under U.S. regulations.[133]

Two species are IUCN Vulnerable: the desert tortoise (California and Nevada) and the gopher tortoise (Georgia, also the official tortoise of Florida).[7][18] Three species are Near Threatened: the diamondback terrapin (Maryland), the ornate box turtle (Kansas), and the common box turtle (Missouri with the three-toed subspecies, North Carolina and Tennessee with the eastern subspecies).[22][26][32] All the remaining state reptile species are Least Concern. All the non-turtle reptiles fall into this category,[nb 14] but the only two turtles in relative safety are the common snapping turtle (New York) and the painted turtle (Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Vermont).[11][37]

The tabulated IUCN ratings for the state reptiles all reflect species-level assessments; for most state reptiles, the IUCN does not discuss the subspecies situations. With the Arizona ridge-backed rattlesnake, the IUCN notes the subspecies has similar safety to the overall species, but does not formally rate the subspecies.[5]

The ratings also do not reflect state-specific population conditions. For instance, for the Texas horned lizard, much of eastern Texas has lost the animal. Nevertheless, based on healthy populations in other parts of the West, especially New Mexico, the IUCN rates the animal Least Concern.[48] For the timber rattlesnake (West Virginia), the IUCN notes the animal as losing range in many parts of the northeastern U.S., but because the animal is numerous in the southern Appalachians, it is also Least Concern.[55]

The IUCN status of state reptiles at the genus level is ambiguous. For Massachusetts's garter snake, the listed Least Concern represents the status of the pictured common garter snake, the species found throughout much of North America and residing in Massachusetts.[28] Within that genus, there are twenty-three species at Least Concern and two each at Vulnerable, Endangered and Data Deficient.[134] For Wyoming's horned lizard state reptile, the rating reflects that of the pictured short-horned lizard, which occurs over much of the central United States and almost all of Wyoming.[58][135] Within that genus, there are ten species at Least Concern and one at Near Threatened and one at Data Deficient.[136]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Excluding Florida's state saltwater reptile and official tortoise from the tally.

- ^ The line does not perfectly separate north and south states because some states extend across it. For example, Missouri, generally considered southern, has territory above the line, and Illinois, generally considered northern, has territory below it.

- ^ The nineteen southern or southwestern states with state reptiles were Alabama,[1][2] Arizona,[2][4] California,[6] Colorado,[10] Florida,[12] Georgia,[19] Kansas,[21] Louisiana,[24] Maryland,[25] Mississippi,[30] Missouri,[31] Nevada,[24] New Mexico,[34] North Carolina,[38] Oklahoma,[43] South Carolina,[45] Tennessee,[46] Texas,[47] Utah,[51] and West Virginia.[55]

- ^ The school newspaper was already named the Diamondback.[109]

- ^ Alabama,[1][2] California,[6] Colorado,[10] Georgia,[19] Illinois,[20] Kansas,[21] Maryland,[25] Michigan,[29] Missouri,[31] Nevada,[24] New York,[36] North Carolina,[38] South Carolina,[45] Tennessee,[46] and Vermont.[53]

- ^ Arizona,[2][4] Massachusetts,[27] Ohio,[40] and West Virginia.[55]

- ^ New Mexico,[34] Oklahoma,[43] Texas,[47] Utah,[51] and Wyoming.[57]

- ^ Florida,[12] Louisiana,[24] and Mississippi.[30]

- ^ Formal taxonomy of reptiles combines lizards and snakes into one order, Squamata, and adds Tuataras (lizard-like creatures from New Zealand, not found in the United States) as an order of reptiles, along with turtles and crocodilians.

- ^ Alabama,[1][2] California,[6] Florida,[12] Georgia,[19] Illinois,[20] Kansas,[21] Louisiana,[24] Maryland,[25] Michigan,[29] Nevada,[24] New Mexico,[34] New York,[36] Oklahoma, South Carolina,[45] Texas,[47] Vermont,[53] and West Virginia.[55]

- ^ Massachusetts,[27] and Wyoming.[57]

- ^ Arizona,[2][4] Colorado,[10] Missouri,[31] North Carolina,[38] Ohio,[40] and Tennessee.[46]

- ^ Florida gives a more specialized saltwater reptile, in addition to its state reptile. For comparison, see marine mammals in "List of U.S. state mammals".

- ^ Non-turtle Least Concern species: Arizona;[5] Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi;[13] Massachusetts;[28] New Mexico;[35] Ohio;[41] Oklahoma;[44] Texas;[48] Virginia;[28] West Virginia;[56] Wyoming.[58]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Official Alabama reptile". Alabama emblems, symbols and honors. Alabama Department of Archives & History. July 12, 2001. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shearer 1994, p. 310

- ^ a b Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (2016) [errata version of 1996 assessment]. "Pseudemys alabamensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T18458A97296493. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T18458A8295960.en. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Shearer 1994, p. 311

- ^ a b c Hammerson, G.A.; Vazquez Díaz, J. & Quintero Díaz, G.E. (2007). "Crotalus willardi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T62253A12584209. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T62253A12584209.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Shearer 1994, p. 312

- ^ a b c Berry, K.H.; Allison, L.J.; McLuckie, A.M.; Vaughn, M. & Murphy, R.W. (2021). "Gopherus agassizii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T97246272A3150871. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T97246272A3150871.en. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Bill Text - AB-1776 State government: Pacific leatherback sea turtle". California Legislative Information. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Wallace, B.P.; Tiwari, M.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T6494A43526147. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T6494A43526147.en. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Colorado State Archives symbols & emblems". colorado.gov. State of Colorado. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Rhodin et al. 2010, p. 000.99.

- ^ a b c d e f Shearer 1994, p. 313

- ^ a b c d Elsey, R.; Woodward, A. & Balaguera-Reina, S.A. (2019). "Alligator mississippiensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T46583A3009637. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T46583A3009637.en. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b "State symbols/Fla. cracker horse/loggerhead turtle (SB 230)". Florida House of Representatives. 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Casale, P. & Tucker, A.D. (2017) [amended version of 2015 assessment]. "Caretta caretta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T3897A119333622. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T3897A119333622.en. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Florida legislation that passed and that failed". St. Petersburg Times. May 4, 2008. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b "15.03861. Official state tortoise. History.—s. 2, ch. 2008–34 (hist)" (scroll down). 2010 Florida statutes (chapter 15). Florida State Legislature. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Gopherus polyphemus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T9403A12983629. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T9403A12983629.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Shearer 1994, p. 314

- ^ a b c d e f "State symbols". Illinois.gov. Archived from the original on June 30, 2010. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Shearer 1994, p. 315

- ^ a b van Dijk, P.P. & Hammerson, G.A. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Terrapene ornata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T21644A97429080. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T21644A9304752.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ "2009-73-1901 Kansas Code patriotic emblems, state reptile, designation". Justia. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shearer 1994, p. 316

- ^ a b c d "Maryland state reptile—diamondback terrapin". Maryland manual on-line: a guide to Maryland government. Maryland State Archives. March 8, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Roosenburg, W.M.; Baker, P.J.; Burke, R.; Dorcas, M.E. & Wood, R.C. (2019). "Malaclemys terrapin". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12695A507698. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T12695A507698.en. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Citizen information service: state symbols". Massachusetts State (Secretary of the Commonwealth). Retrieved January 21, 2011.

The Garter Snake became the official reptile of the Commonwealth on January 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Frost, D.R.; Hammerson, G.A. & Santos-Barrera, G. (2015). "Thamnophis sirtalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T62240A68308267. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T62240A68308267.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Michigan's state symbols" (PDF). Michigan History. 100. May 2002.

- ^ a b c d e "SB 2069 history of actions". Mississippi Legislature. 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

The American Alligator to be designated as the Mississippi State Reptile; provide...02/21 Approved by Governor

- ^ a b c d e f "State symbols of Missouri: state reptile". Missouri Secretary of State Robin Carnihan. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Terrapene carolina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T21641A97428179. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T21641A9303747.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Bog turtle becomes New Jersey's state reptile". Associated Press. June 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Chapter VIII. New Mexico state animals" (PDF). New Mexico Envirothon. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Hammerson, G.A.; Lavin, P.; Vazquez Díaz, J.; Quintero Díaz, G. & Gadsden, H. (2007). "Aspidoscelis neomexicana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T64278A12752324. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64278A12752324.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "New York state information". New York State Library. 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Rhodin et al. 2010, p. 000.92.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shearer 1994, p. 321

- ^ "Official state symbols of North Carolina". North Carolina State Library. State of North Carolina. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "5.031 State reptile". LAWriter: Ohio Laws and Rles. Lawriter LLC. 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Hammerson, G.A.; Acevedo, M.; Ariano-Sánchez, D. & Johnson, J. (2013). "Coluber constrictor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T63748A3128579. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T63748A3128579.en. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Oklahoma state icons". Oklahoma Department of Libraries. Archived from the original on 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ a b c Shearer 1994, p. 322

- ^ a b Hammerson, G.A.; Lavin, P.; Vazquez Díaz, J.; Quintero Díaz, G. & Gadsden, H. (2007). "Crotaphytus collaris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T64007A12734318. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64007A12734318.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Shearer 1994, p. 323

- ^ a b c d e f "Tennessee symbols and honor" (PDF). Tennessee Blue Book: 526. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Texas state symbols". About Texas. Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c Hammerson, G.A. (2007). "Phrynosoma cornutum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T64072A12741535. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64072A12741535.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Texas. Legislature. House of Representatives. 83rd Texas Legislature, Regular Session, House Concurrent Resolution 31, legislative document, May 10, 2013; [Austin, Texas]. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth438883/: accessed July 22, 2020), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department.

- ^ Wibbels, T. & Bevan, E. (2019) [errata version of 2019 assessment]. "Lepidochelys kempii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T11533A155057916. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T11533A155057916.en. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "HB0144". le.utah.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ Hammerson, G.A.; Frost, D.R. & Gadsden, H. (2007). "Heloderma suspectum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T9865A13022716. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T9865A13022716.en. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Joint resolution relating to the designation of the painted turtle as the state reptile (J.R.S. 57)". Vermont Legislature. 1994. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ "Bill Tracking - 2016 session > Legislation". Legislative Information System. Virginia's Legislative Information System. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Senate concurrent resolution 28 (bill status 2008 regular session)". West Virginia Legislature. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Hammerson, G.A. (2007). "Crotalus horridus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T64318A12765920. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64318A12765920.en. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "State symbols". Wyoming Secretary of State's Office. 2011. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c Hammerson, G.A. (2007). "Phrynosoma hernandesi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T64076A12741970. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64076A12741970.en. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Samuel, David (November 8, 2009). "What are our state animals?". Morgantown Dominion Post. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ Abellera, Bonnie. "Loggerhead sea turtle is a new state symbol". FWC. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "The voting is over: students nominate common snapping turtle as official state reptile". Assemblyman Joel M. Miller. April 26, 2006. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Minnesota state symbols—unofficial, proposed, or facetious". Minnesota State Legislature. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Regular session 2009–2010: House bill 621". Pennsylvania State Legislature. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "SB 1504 Eastern box turtle; designating as official state reptile". Virginia State Legislature. 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Associated Press (February 20, 2009). "Virginia House crushes box turtle's bid to be state reptile". NBC Washington. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Shearer 1994, p. 309

- ^ "Eastern box turtle—North Carolina state reptiles". North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "State symbols: Maryland state symbol—diamondback terrapin". msa.md.gov. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Ohio's state symbols". Ohio Governor's Residence and Heritage Garden. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "House Concurrent Resolution No. 141". Texas State Legislature. May 27, 1993. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Illinois state smbols lesson plan: state symbols review" (PDF). Illinois state symbols and their history. Illinois State Museum. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Long, Jennifer. "Alabama patriotic symbols". Lesson plans. Alabama Learning Exchange. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ "The living state symbols of Arizona" (PDF). Arizona Game and Fish Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ "North Carolina state symbols". State of North Carolina kids page. North Carolina Secretary of State's Office. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "New York state symbols". NYS kids room. New York Department of State. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Missouri kids!". Missouri Secretary of State's Office. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "They stand for us. Symbols of Missouri. A resource book for Missouri students" (PDF). Missouri kids!. Missouri Secretary of State's Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Shearer 1994, p. 167

- ^ "Official state mammals". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Official state fish". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Official state insects". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Official state amphibians". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Official state dogs". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Official state dinosaurs". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Official state bats". netstate.com. NSTATE, LLC. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Louisiana facts". Other services. Louisiana Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Maryland state crustacean: blue crab". Maryland state symbols: state symbols. Maryland state archives. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "House bills: HJR 37". Oregon State Legislature. 2009. Archived from the original (scroll down) on January 4, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Shearer 2003, pp. 97–146

- ^ a b c Shearer 2003, pp. 225–248

- ^ Smith, Hobart M.; Brodie, Edmund (1982). Reptiles of North America: a guide to field identification. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-58238-123-7.

In North America, reptiles are most abundant in the warmer southern regions.

- ^ "Official symbols of the District of Columbia". District of Columbia Government. Archived from the original on February 5, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Official fish of the District of Columbia". Council of the District of Columbia. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Official amphipod of the District of Columbia". Council of the District of Columbia. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "D.C. Law 23-160. Big Brown Bat Official State Mammal Designation Act of 2020". Council of the District of Columbia. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Hearing notice: Red-backed salamander official state amphibian designation act of 2024" (PDF). Council of the District of Columbia. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Shearer 2003, pp. 245–246

- ^ "State trees and state flowers". usna.usda.gov. The United States National Arboretum. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Details about Guam". ns.gov.gu. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Social and economic indicators". Guam's facts and figures at a glance. Bureau of Statistics and Plans: Office of the Governor. 2005. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Leepson, Marc; DeMille, Nelson (2005). Flag: an American biography. Macmillan. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-312-32309-7.

- ^ "The U.S. Navy's First Jack". Frequently asked questions. Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. July 28, 2003. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Waggy, Chuck (Summer–Fall 2009). "State reptile" (PDF). West Virginia Wildlife. 9 (2): 13–16.

- ^ DeFord, Deborah H. (2007). The American Revolution. Pleasantville, New York: Gareth Stevens. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8368-7298-9.

- ^ Boller, Paul F. (2004). Presidential campaigns: from George Washington to George W. Bush. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-516716-0.

- ^ "Recipes from another time". Smithsonian. October 2001.

- ^ Livingston, A. D. (1996). Complete fish & game cookbook. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole books. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8117-0428-1.

- ^ "History: 1906–1927, early Gainesville". University of Florida. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Testudo: Tale of the Top Shell". CBSSports.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Nancy, Bartosek. "Frog of ages". The TCU Magazine. Texas Christian University. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Klauber, Laurence Monroe (1972). Rattlesnakes: their habits, life histories, and influence on mankind, volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-520-01775-7.

- ^ Smith, Hobart M.; Zim, Herbert Spencer (1953). Reptiles and amphibians: a guide to familiar American species. New York: Golden Press. p. 9. as cited by Gibbons, J. Whitfield. "The management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America: the need for an environmental attitude adjustment" (PDF). Symposium as titled, Flagstaff, Arizona, July, 1988. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Hobart M.; Zim, Herbert Spencer (2001). Reptiles and amphibians: a guide to familiar American species. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-58238-131-2.

- ^ Gibbons, J. Whitfield. "The management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America: the need for an environmental attitude adjustment" (PDF). Symposium as titled, Flagstaff, Arizona, July, 1988. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Rhodin, A. (August 13–16, 1999). Celebrate the turtle: perception and preservation. 4th occasional freshwater turtle conference. Laughlin, NV. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Carr, Archie (1952). Handbooks of American Natural History: Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Binghamton, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates a Division of Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8254-0. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Roosenburg, W. M. (1991). "The diamondback terrapin: population dynamics, habitat requirements, and opportunities for conservation". In Mihurskey, J. A.; Chaney, A. (eds.). New perspectives in the Chesapeake system: a research and management partnership (PDF). Baltimore, MD: Chesapeake Research Consortium. pp. 227–234.

- ^ Lieberman, Susan (1994). "Can CITES save the box turtle?". Endangered Species Technical Bulletin. 19 (1): 16–17. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Brown, William S. (1993). Collins, Joseph T. (ed.). Biology, status, and management of the timber rattlesnake. Herpetological Circular. Vol. 22. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. ISBN 978-0-916984-29-8.

- ^ David, D.; Brunell, A. M.; Carbonneau, D. A.; Dutton, H.J.; Hord, L. J.; Wiley, N.; Woodward, A.R. (1996). "Florida's alligator management program, an update — 1987–1995". Proceedings of the thirteenth working meeting of crocodile specialist group. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. pp. 410–428. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ King, F. W. (1989). "Conservation and management". In Ross, C. A.; Garnett, S. (eds.). Crocodiles and alligators. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 216–229. ISBN 978-0-8160-2174-1. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Guyer, C.; Bailey, M. A. (1993). "Amphibians and reptiles of longleaf pine communities". In Herman, S. M. (ed.). The longleaf pine ecosystem:ecology, restoration and management. Proceedings of the tall timber fire ecology conference, number 18. Tall Timbers Research Station. pp. 139–158. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Lovich, J. E. (Summer 1995). "Wildlife and weeds: life in an alien landscape" (PDF). CalEPCC News. Vol. 3, no. 3. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Stewart, M. C.; Austin, D. F.; Bourne, J. R. (1993). "Habit structure and the dispersion of gopher tortoises on a nature preserve". Florida Scientist. 56: 70–81. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Goin, J. W. (August 1992). "Requim or recovery?". Texas Parks Wildlife. pp. 28–35. as cited by Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, D. E.; Ryan, T. J.; Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B. S.; Greene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.; Winne, C.T. (August 2000). "The global decline of reptiles, deja vu amphibians" (PDF). BioScience. 50 (8): 653–666. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0653:tgdord]2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Guillette, L. J.; Gross, T. S.; Masson, G. R.; Matter, J. M.; Percival, H. F.; Woodward, A. R. (August 1994). "Developmental abnormalities of the gonad and abnormal sex hormone concentrations in juvenile alligators from contaminated and control lakes in Florida". Environmental Health Perspectives. 102 (8): 680–688. doi:10.1289/ehp.94102680. PMC 1567320. PMID 7895709. Archived from the original on 2006-02-19.

- ^ Jacobson, E. R. (March 1993). "Implications of Infectious Diseases for Captive Propagation and Introduction Programs of Threatened/Endangered Reptiles". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 24 (3): 2–17 and 245–255. JSTOR 20095276.

- ^ Jacobson, E. R. (September 1994). "Causes of mortality and disease in tortoises: a review" (PDF). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 25 (1): 2–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24.

- ^ Smith, R.B.; Seigel, R. A.; Smith, K. R. (September 1998). "Occurrence of upper respiratory tract disease in gopher tortoise populations in Florida and Mississippi". Journal of Herpetology. 32 (3): 426–430. doi:10.2307/1565458. JSTOR 1565458.

- ^ Schneider, S. H.; Root, T. L. (1998). "Impacts of climate changes on biological resources". In Mac, M. J.; Opler, P. A.; Puckett, C. E.; Haecker; Doran, P. D. (eds.). Status and trends of the nation's biological resources volume 1 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 89–116.

- ^ "Species profile: Alabama red-belly turtle (Pseudemys alabamensis)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Species profile: loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "IUCN search Thamnophis". The IUCN red list of threatened species. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ Pianka, Erik R.; Hodges, Wendy L. "Horned lizards". Varanus : the Pianka lab page. University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "IUCN search Phrynosoma". The IUCN red list of threatened species. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the world, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5: 000.89 – 000.138. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- Shearer, Benjamin F.; Shearer, Barbara S. (1994). State names, seals, flags, and symbols (2nd ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-28862-3.

- Shearer, Benjamin F.; Shearer, Barbara S. (2003). State names, seals, flags, and symbols (3rd ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31534-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Reptiles of the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Reptiles of the United States at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF