List of Underground Railroad sites

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 21 min

The list of Underground Railroad sites includes abolitionist locations of sanctuary, support, and transport for former slaves in 19th century North America before and during the American Civil War. It also includes sites closely associated with people who worked to achieve personal freedom for all Americans in the movement to end slavery in the United States.

The list of validated or authenticated Underground Railroad and Network to Freedom sites is sorted within state or province, by location.

Canada

[edit]

The Act Against Slavery of 1793 stated that any enslaved person would become free on arrival in Upper Canada. A network of routes led from the United States to Upper and Lower Canada.[1]

Ontario

[edit]- Amherstburg Freedom Museum – Amherstburg.[2] The museum uses historical artifacts, Black heritage exhibits, and video presentations to share the story of how Africans were forced into slavery and the made their way to Canada.[3]

- Fort Malden – Amherstburg[4] One of the routes to Ontario was to cross Lake Erie from Sandusky, Ohio to Fort Malden. Another route to Fort Malden was traveling across the Detroit River into Canada and then across to Amherstburg. A number of fugitive slaves lived in the area and Isaac J. Rice established himself as a missionary, operating a school for black children.[5]

- Buxton National Historic Site and Elgin settlement – Chatham, Ontario[1][6] The Elgin settlement was established by a Presbyterian minister, Reverend William King, with fifteen former slaved on November 28, 1849. King came from Ohio, where he inherited fourteen enslaved people from his father-in-law and acquired another and set them free. King intended the Elgin settlement to a refuge for runaway enslaved people. The Buxton Mission was established at the settlement.[7]

- Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site and Dawn Settlement – Dresden.[1][2] Rev. Josiah Henson, a former enslaved man who fled slavery via the Underground Railroad with his wife Nancy and their children, was a cofounder of the Dawn Settlement in 1841. Dawn Settlement was designed to be a community for black refugees, where children and adults could receive an education and develop skills so that they could prosper. They exported tobacco, grain, and black walnut lumber to the United States and Britain.[8]

- John R. Park Homestead Conservation Area – Essex. The Park Homestead was a station on the Underground Railroad.[9][10]

- John Freeman Walls Historic Site – Lakeshore.[1][2] John Freeman Walls, left his enslavers in North Carolina and settled in Canada. The Refugee Home Society supplied the money to buy land and he built a cabin. Church services were held there before the Puce Baptist Church was built. It was also a terminal stop on the Underground Railroad. Walls and his family stayed in Canada after the American Civil War.[11]

- Queen's Bush – Mapleton.[1] Beginning in 1820, African American pioneers settled in the open lands of Queen's Bush. More than 1,500 blacks set up farms and created a community with churches and Mount Pleasant and Mount Hope schools, which were taught by American missionaries.[12]

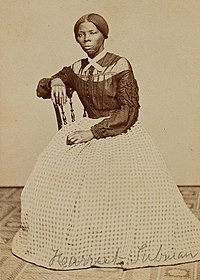

- St. Catharines – Harriet Tubman lived in St. Catharines and attended the Salem Chapel for ten years. After she freed herself from slavery, she helped other enslaved people reach freedom in Canada. The town was a final stop on the Underground Railroad for many people.[13]

- Sandwich First Baptist Church – Windsor.[1] The church was built just over the border from the United States in Windsor, Ontario by blacks who came to Canada to live free. For its role in the lives of its congregants and as a sanctuary for fugitive slaves, it was designated a National Historic Site in 1999.[14]

Nova Scotia

[edit]African-American people settled in Nova Scotia since 1749.[15]

- Birchtown National Historic Site – Birchtown.[1] It was a settlement of black people from Colonial America, who served the British during the American Revolutionary War in exchange for their freedom. Birchtown was the largest community of free black people in British North America during the late 18th century.[1][16]

- Africville – Halifax.[1] Black people settled in Africville beginning in 1848. Black residents did not have the same services as white people, like clean water and sewers, and lived on land that was not arable. Some were able to make a living for themselves and build a community with a Baptist church, a school, stores, and a post office. A plan was initiated to relocate families and raze the site of the town.[15]

United States

[edit]Colorado

[edit]- Barney L. Ford Building — Denver, associated with escaped slave Barney Ford, who became a quite successful businessman and led political action towards Black voting rights in Colorado.[17] He used the Underground Railroad (UGRR) to flee slavery and supported UGRR activities.[18]

Connecticut

[edit]

- Francis Gillette House — Bloomfield[19]

- Austin F. Williams Carriagehouse and House — Farmington.[17] Built in the mid-19th century, the property was designated a National Historic Landmark for the role it played in the celebrated case of the Amistad Africans, and as a "station" on the Underground Railroad.[20]

- First Church of Christ, Congregational — Farmington[21] The church was a hub of the Underground Railroad, and became involved in the celebrated case of the African slaves who revolted on the Spanish vessel La Amistad. When the Africans who had participated in the revolt were released in 1841, they came to Farmington.[20]

- Polly and William Wakeman House — Wilton. The Wakemans were among a group of abolitionists in Wilton who helped runaway slaves. Underneath their house was a tunnel that was accessed by a trap door. They took people on late-night trips to neighboring towns on the Underground Railroad.[22][23]

Delaware

[edit]- Camden Friends Meetinghouse — Camden[24] Quaker meeting house (built in 1806) of Camden Monthly Meeting, several of whose members were active in the Underground Railroad, including John Hunn, who is buried in its cemetery.

- John Dickinson Plantation — Dover[24]

- New Castle Court House — New Castle[17]

- Appoquinimink Friends Meetinghouse — Odessa[17]

- Corbit–Sharp House — Odessa[24]

- The Tilly Escape site, Gateway to Freedom: Harriet Tubman's Daring Route through Seaford — Seaford[24][25]

- Friends Meeting House — Wilmington[17]

- Thomas Garrett House — Wilmington[24]

District of Columbia

[edit]- Blanche K. Bruce House[24]

- Camp Greene and Contraband Camp[24]

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site[17]

- Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center[24]

- Leonard Grimes Property Site[24]

- Mary Ann Shadd Cary House[17]

- Pearl incident at 7th Street Dock[24][26]

Florida

[edit]- Negro Fort, also known as British Fort and Fort Gadsden — near Sumatra, Franklin County[17][27]

- Fort Mosé — St. John's County[17]

Georgia

[edit]- First African Baptist Church — Savannah[27]

- Dr. Robert Collins House - William and Ellen Craft Escape Site (NRHP site) — Macon[24]

Illinois

[edit]- Old Rock House — Alton[28][29][30]

- New Philadelphia Town Site — Barry[24]

- Quinn Chapel AME Church — Brooklyn[24]

- Lucius Read House — Byron[24]

- Galesburg Colony UGRR Freedom Station at Knox College — Galesburg[24]

- Beecher Hall, Illinois College — Jacksonville[17]

- Graue Mill — Oak Brook[27][31]

- Dr. Hiram Rutherford House and Office — Oakland[17]

- Owen Lovejoy House — Princeton[17]

- John Hossack House — Ottawa[17]

- Dr. Richard Eells House — Quincy[17][32]

- Maple Lane (Reverend Asa Turner House) – Quincy[33]

- Mission Institute Number One – Quincy[34][33]

- Mission Institute Number Two – Quincy[34][33]

- Oakland (Dr. David Nelson House) – Quincy[34][33]

- Blanchard Hall, Wheaton College — Wheaton[24]

Indiana

[edit]

- Levi Coffin House — Fountain City[17]

- Bethel AME Church — Indianapolis[17]

- Eleutherian College Classroom and Chapel Building — Lancaster[17]

- Lyman and Asenath Hoyt House — Madison[17]

- Madison Historic District — Madison[17]

- Town Clock Church (now Second Baptist Church) — New Albany[35]

- Quinn House, within Old Richmond Historic District — Richmond[27]

- Phanuel Lutheran Church — Southeastern Fountain County[36]

Iowa

[edit]- First Congregational Church — Burlington[37]

- Horace Anthony House — Camanche[38]

- Reverend George B. Hitchcock House — Lewis vicinity[17]

- Henderson Lewelling House — Salem[17]

- Todd House — Tabor[17]

- Jordan House — West Des Moines[17]

Kansas

[edit]- Fort Scott National Historic Site — Bourbon County[17]

- John Brown Cabin — Osawatomie[17]

Maine

[edit]- Harriet Beecher Stowe House — Brunswick[17]

- Abyssinian Meeting House — Portland[17]

- Maple Grove Friends Church — Fort Fairfield

- Private Home - 55 High St Brownsville, ME

Maryland

[edit]

- President Street Station — Baltimore[27]

- Harriet Tubman's birthplace — Dorchester County[39][40]

- Riley-Bolten House — North Bethesda[17]

- John Brown's Headquarters — Sample's Manor[17]

Massachusetts

[edit]- African American National Historic Site — Boston[17]

- William Lloyd Garrison House — Boston[17]

- Black Heritage Trail, including the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House — Boston[27][24][41]

- William Ingersoll Bowditch House — Brookline[17]

- Mount Auburn Cemetery — Cambridge[17]

- The Wayside — Concord[17]

- George Luther Stearns Estate — Medford[42]

- Nathan and Mary Johnson House — New Bedford[17]

- Jackson Homestead — Newton[17]

- Ross Farm — Northampton[17]

- Dorsey–Jones House — Northampton[17]

- Liberty Farm — Worcester[17]

Michigan

[edit]- Guy Beckley — Ann Arbor. Underground Railroad promoter and station master and anti-slavery lecturer. The Guy Beckley House is on the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.[43]

- Erastus and Sarah Hussey — Battle Creek[44]

- Second Baptist Church — Detroit[17]

- Dr. Nathan M. Thomas House — Schoolcraft[17]

- Wright Modlin — Williamsville, Cass County. His house was a railroad station, but he often traveled south to the Ohio River (a border between the free and slave states) or into Kentucky where he found people escaping slavery and brought them up to Cass County. He was so successful that it angered Kentuckian slaveholders, who instigated the Kentucky raid on Cass County in 1847. He was also a central figure in The South Bend Fugitive Slave case.[45]

Nebraska

[edit]- Mayhew Cabin — Nebraska City[17]

New Jersey

[edit]

- Holden Hilton House — Jersey City[46]

- Thomas Vreeland Jackson and John Vreeland Jackson house — Jersey City[46]

- Mott House — Lawnside Borough[17][47]

- Red Maple Farm — Monmouth Junction[48]

- Grimes Homestead — Mountain Lakes[17][47]

- Rhoads Chapel — Saddlertown, Haddon Township[49]

- Bethel AME Church — Springtown[17][47]

- Mortonson-Van Leer Log Cabin — Swedesboro[50]

- Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church — Woolwich Township[17][47]

New York

[edit]- Edwin Weyburn Goodwin — Albany[51]

- Stephen and Harriet Myers House — Albany[24][52]

- Allegany County network: Baylies Bassett — Alfred and others (including Henry Crandall Home — Almond; William Sortore Farm — Belmont); Marcus Lucas Home — Corning; Thatcher Brothers — Hornell, McBurney House — Canisteo (now in town of Hornellsville); William Knight — Scio[53][54]

- Harriet Tubman House and Thompson AME Zion Church — Auburn[17][55]

- North Star Underground Railroad Museum — Ausable Chasm[17][53]

- Michigan Street Baptist Church — Buffalo[27]

- Cadiz, Franklinville area network: Merlin Mead House and others, including John Burlingame, Alfred Rice, Isaac Searle, and the owner of the Stagecoach Inn[56]

- McClew Farm at Murphy Orchards — Burt[24][57]

- St. James AME Zion Church — Ithaca[17][52]

- John Brown Farm State Historic Site — Lake Placid[17]

- Starr Clock Tinshop — Mexico[17]

- Abolitionist Place — New York City: Brooklyn. Abolitionist Place is a section of Duffield Street in downtown Brooklyn that used to be a center of anti-slavery and Underground Railroad activity. New York City was one of the busiest ports in the world in the 19th century. Some freedom seekers traveled aboard ships amongst cargo, like tobacco or cotton from the Southern United States and arrived in Brooklyn a few blocks away from Abolitionist Place. Underground Railroad conductors helped these freedom seekers, as well as people who traveled north on the Underground Railroad. They were provided needed shelter, like at the Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims; clothing; and food.[58]

- Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims — New York City: Brooklyn[17][52]

- Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center — Niagara Falls[55]

- Chappaqua Friends Meeting House - Chappaqua, New York[59]

- Buckout-Jones Building — Oswego[24]

- Edwin W. and Charlotte Clarke House — Oswego[17][24]

- Hamilton and Rhoda Littlefield House — Oswego[24]

- John B. and Lydia Edwards House — Oswego[17][24]

- John Jay Homestead - Bedford/Katonah[59]

- Orson Ames House — Mexico, Oswego County[17]

- Oswego Market House — Oswego[24]

- Oswego School District Public Library (presumably the Oswego City Library) — Oswego[24]

- Richardson-Bates House Museum — Oswego[24]

- Tudor E. Grant — Oswego[24]

- Gerrit Smith Estate and Land Office — Peterboro[17]

- Smithfield Community Center — Peterboro, formerly a church; first meeting of New York Anti-Slavery Society held there; houses National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.[60]

- Samuel and Elizabeth Cuyler House Site — Pultneyville[24]

- Foster Memorial AME Zion Church — Tarrytown[17][52]

- Eber Pettit Home - Versailles[56]

- African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church - Rochester, New York. Escaping enslaved people were hidden under the pulpit and in hollow pews. Frederick Douglass, Amy and Isaac Post, Jacob P. Morris, and other Rochester Underground Railroad organizers were associated with the site.[61]

North Carolina

[edit]- Guilford College Woods meeting place, Guilford College — Greensboro[62]

- Freedmen's Colony of Roanoke Island Network to Freedom site — Manteo, Outer Banks[24][63]

Ohio

[edit]

- Col. William Hubbard House — Ashtabula[17]

- Captain Jonathan Stone House — Belpre[64]

- Harriet Beecher Stowe House — Cincinnati[17]

- House of Peter and Sarah M. Fossett — Cincinnati / Cumminsville[65][66]

- Samuel and Sally Wilson House — Cincinnati[17]

- James and Sophia Clemens Farmstead — Greenville[17]

- Sawyer–Curtis House — Little Hocking[67]

- Mount Pleasant Historic District — Mt. Pleasant[17]

- Reuben Benedict House — Marengo[17]

- Spring Hill — Massillon[17]

- Wilson Bruce Evans House — Oberlin[17]

- John P. Parker House — Ripley[17]

- John Rankin House — Ripley[17]

- Daniel Howell Hise House — Salem[17]

- Rush R. Sloane House — Sandusky[17]

- George W. Adams House / Prospect Place — Trinway[68]

- Iberia — Washington Township, Morrow County[69]

- Putnam Historic District — Zanesville[17]

Pennsylvania

[edit]

- Kaufman's Station — Boiling Springs[24]

- Oakdale — Chadds Ford[17]

- John Brown House — Chambersburg[17]

- Dobbin House — Gettysburg[27]

- Thaddeus Stevens Home and Law Office – Lancaster[24]

- Johnson House — Philadelphia[17]

- Hosanna Meeting House — Chester County[70]

- Liberty Bell, Independence National Historical Park — Philadelphia[27]

- White Horse Farm — Phoenixville[17]

- Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall — Plymouth Meeting[71]

- Bethel AME Zion Church — Reading[17]

- F. Julius LeMoyne House — Washington[17]

- William Goodrich House — York[24][27]

- Eusebius Barnard House — Pocopson[72]

- Van Leer Cabin — Tredyffrin

Rhode Island

[edit]- Isaac Rice Homestead — Newport[27]

Tennessee

[edit]

- Burkle Estate was possibly a station and is now Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum — Memphis[27][73]

- Hunt-Phelan House — Memphis[27][74]

Texas

[edit]Vermont

[edit]Virgin Islands

[edit]- Annaberg Sugar Plantation and School — St. John[27]

Virginia

[edit]- Bruin's Slave Jail — Alexandria[17]

- Rochelle–Prince House / Nat Turner Historic District — Courtland[27]

- Moncure Conway House — Falmouth[17]

- Theodore Roosevelt Island — Rosslyn[17]

- Fort Monroe — Hampton[17]

West Virginia

[edit]- Z. D. Ramsdell House — Ceredo[75]

- Jefferson County Courthouse — Charles Town[17]

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park — Harpers Ferry[17]

- Wheeling Hotel — Wheeling[27]

Wisconsin

[edit]- Milton House — Milton[17]

- Joshua Glover — Milwaukee[24]

- Lyman Goodnow — Waukesha. Conductor, led 16-year-old Caroline Quarlls, the first known freedom seeker along Wisconsin's Underground Railroad, from Wisconsin to Canada.[76]

Other articles and references

[edit]See also

[edit]- Index: Underground Railroad locations

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

- The Underground Railroad Records

- Underground Railroad Bicycle Route

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Underground Railroad". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ a b c Cooper, Afua (February 24, 2017). "At Ontario Underground Railroad Sites, Farming and Liberty". www.nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ "Amherstburg Freedom Museum". Ontario Heritage Trust. 2017-02-22. Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ Tom Calarco, Places of the Underground Railroad: A Geographical Guide (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2011), 16.

- ^ "Levi Coffin, 1798-1877. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the Reputed President of the Underground Railroad; Being a Brief History of the Labors of a Lifetime in Behalf of the Slave, with the Stories of Numerous Fugitives, Who Gained Their Freedom Through His Instrumentality, and Many Other Incidents". docsouth.unc.edu. p. 143, 249. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "5 Canadian stations of the Underground Railroad". CBC.

- ^ "Settlements in Canada - Underground Railroad". PBS. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "The Ontario Heritage Trust". Ontario Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ "John R. Park Homestead Conservation Area, Essex Region Conservation Authority". Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 2021-06-06. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ^ "Black History-From Slavery to Settlement". www.archives.gov.on.ca. Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ^ "John Freeman Walls Underground Railroad Museum". Ontario Heritage Trust. 2017-02-22. Archived from the original on 2021-02-10. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "The Ontario Heritage Trust". Ontario Heritage Trust. 2016-12-08. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ "5 Canadian Heritage Sites to Visit during Black History Month". Trans Canada Trail. 2018-02-16. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ "Sandwich First Baptist Church National Historic Site of Canada". www.pc.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ a b "The story of Africville". CMHR. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ "Black Loyalist Heritage Site". Tourism Nova Scotia. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf "List of Sites for the Underground Railroad Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-05-29. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ "Barney Ford: African American Pioneer". www.historycolorado.org. History Colorado. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Francis Gillette House". National Park Service. and accompanying photos

- ^ a b Cunningham, Jan (September 15, 1996). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Austin F. Williams Carriagehouse and House" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying 10 photos, exterior and interior, from 1996 and undated (3.49 MB)

- ^ "Underground Railroad - Special Resource Study - 42 UGRR sites" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 46–47. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "List of Sites - Underground Railroad - Connecticut Freedom Trail". ctfreedomtrail.org. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- ^ "URR Trail: Wilton". www.ctmq.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Network to Freedom listings" (PDF). National Park Service. July 5, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "Gateway to Freedom: The Tilly Escape". Delaware Public Archives - State of Delaware. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ "Washington's Ties To the Underground Railroad: A Look At Where The Enslaved Once Stood". WAMU. Archived from the original on 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Underground Railroad - Special Resource Study - 42 UGRR sites" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 30–44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Snodgrass 2008.

- ^ "Our Past: Old Rock House finished in 1835". 2017-09-06. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Eligon, John (2010-05-13). "Strolling Old Halls and Streets With Ghosts of Civil War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Van Matre, Lynn (March 28, 1999). "Graure Home Restoration Unearths a Mystery". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2021-10-31. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Aboard the Underground Railroad--Dr. Richard Ells House". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ a b c d Deters, Ruth (2008). The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House! How the intriguing story of Dr. David Nelson's home uncovered a region of secrets. Quincy, Illinois: Eleven Oaks Publishing. pp. 70–75, 117–131, 154–156. ISBN 978-0-578-00213-2.

- ^ a b c "Quincy's History". Quincy Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "New Albany Underground Railroad site wins restoration prize". Indiana Landmarks. 2018-03-22. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Church continues 175-year tradition". Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- ^ "History of the Church". First Congregational Church. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ LeRoy C. Goddard. "Horace Anthony House". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ^ "Historic Find: Archaeologists discover home of Harriet Tubman's father". The News Journal. 2021-04-25. pp. A26. Archived from the original on 2021-05-26. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation -- Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument". whitehouse.gov. 2013-03-25. Archived from the original on 2021-06-10. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ^ Site 6 - Lewis and Harriet Hayden House - 66 Phillips Street Archived 2016-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. African American Museum, Boston. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "Mark the Spot: Underground Railroad in Medford". Tufts Now. 2015-02-06. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Snodgrass 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Ingall, David; Risko, Karin (2015-04-13). Michigan Civil War Landmarks. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-62585-466-7.

- ^ Snodgrass 2008, p. 348.

- ^ a b Karnoutsos, Carmela. "Underground Railroad". Jersey City Past and Present. New Jersey City University. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ a b c d "The Official Web Site for The State of New Jersey". www.state.nj.us. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ Switala, William J. (2006), Underground railroad in New Jersey and New York, ISBN 978-0-8117-3258-1

- ^ History Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, Saddler's Woods Conservation Association

- ^ "Historical Sites, Mortonson-Schorn Log Cabin". Gloucester County, New Jersey. Archived from the original on 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ Snodgrass 2008, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d "Underground Railroad". www.iloveny.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ a b Jordan, Jason. "Follow the orange to freedom". Archived from the original on 2021-08-01. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Oldest house in Steuben County, NY - Underground Railroad Sites on Waymarking.com, http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMEW9J_Oldest_house_in_Steuben_County_NY Archived 2017-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Underground Railroad sites in New York". amsterdamnews.com. 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ a b "Underground Railroad". Historic Path of Cattaraugus County. Archived from the original on 2021-08-01. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Sharp, Teresa. "Take a step back in time at historic McClew farmstead in Burt". Archived from the original on 2021-10-31. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ "Abolitionist Place". Mapping the African American Past, Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b "How Westchester County Impacted The Underground Railroad". 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "About SCC 200 More". National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum. 2000.

- ^ "African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church". Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ "About Guilford - Guilford College". Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ "Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony". www.visitnc.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Burke, Henry Robert; Fogle, Charles Hart (2004). Washington County Underground Railroad. Arcadia Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7385-3256-1. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Peter Fossett". www.monticello.org. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "Last of Jefferson's Slaves". The Boston Globe. January 8, 1901. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Burke, Henry Robert; Fogle, Charles Hart (2004). Washington County Underground Railroad. Arcadia Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7385-3256-1. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "G.W. Adams Educational Center". Archived from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "Wilbur H. Siebert Underground Railroad Collection". Ohio History Connection. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Elizabeth, Shultz (2014-03-26). "Hosanna Church: The Last Building in Hinsonville". Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Blog. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ Daley, Jason (October 29, 2018). "Developers and Preservationists Clash Over Underground Railroad Stop". Archived from the original on 2021-04-06. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Explore Network to Freedom Listings - Underground Railroad". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-11-22.

- ^ Clark, Kym (November 17, 2020). "5 Star Stories: The story of Memphis' role in the road to freedom on the Underground Railroad". Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ "Underground Railroad, Special Resource Study" (PDF). National Park Service. September 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Town of Ceredo. "Ramsdell House". Town of Ceredo, West Virginia. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Snodgrass 2008, p. 268.

Bibliography

[edit]- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2008). The Underground Railroad : an encyclopedia of people, places, and operations. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-8093-8.

KSF

KSF