List of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 45 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 45 min

This is a list of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes.

Continental Celts

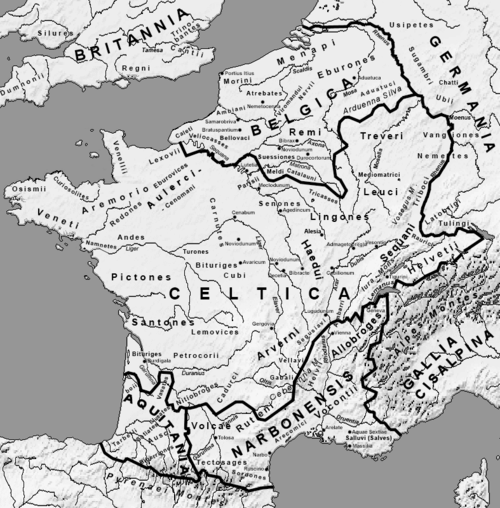

[edit]Continental Celts were the Celtic peoples that inhabited mainland Europe. In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Celts inhabited a large part of mainland Western Europe and large parts of Western Southern Europe (Iberian Peninsula), southern Central Europe and some regions of the Balkans and Anatolia. They were most of the population in Gallia, today's France, Switzerland, possibly Belgica – far Northern France, Belgium and far Southern Netherlands, large parts of Hispania, i.e. Iberian Peninsula – Spain and Portugal, in the northern, central and western regions; southern Central Europe – upper Danube basin and neighbouring regions, large parts of the middle Danube basin and the inland region of Central Asia Minor or Anatolia. They lived in these many regions forming a large arc stretching across from Iberia in the west to the Balkans and Anatolia in the east. Many of the populations from these regions were called Celts by ancient authors. They are thought to have spoken Gaulish (P-Celtic type), Lepontic (P-Celtic type), Hispano-Celtic (Celtiberian and Western Hispano-Celtic or Gallaecian) (Q-Celtic type), Eastern Celtic or Noric (unknown type). P-Celtic type languages are more innovative (*kʷ > p) while Q-Celtic type languages are more conservative. However, it is not fully known if this grouping of peoples, such as their languages, is a genealogical one (phylogenetic), based on kinship, or if it is a simple geographically based group. Classical Antiquity authors did not describe the peoples and tribes of the British Islands as “Celts” or “Galli” but by the name “Britons”. They only used the name “Celts” or “Galli” for the peoples and tribes of mainland Europe.[1]

Eastern Celts

[edit]Source:[2]

They lived in Southern Central Europe (in the Upper Danube basin and neighbouring regions) which is hypothesized as the original area of the Celts (Proto-Celts), corresponding to the Hallstatt Culture. Later they expanded towards the Middle Danube valley and to parts of the Balkans and towards inland central Asia Minor or Anatolia (Galatians). Hercynian Forest (Hercynia Silva), north of the Danube and east of the Rhine was in their lands. Celts, especially those from Western and Central Europe, were generally called by the Romans “Galli” i.e. “Gauls”, this name was synonym of “Celts”, this also means that not all of the peoples and tribes called by the name “Gauls” (Galli) were specifically Gauls in a narrower more regional sense. Their language is scarcely attested and can not be classified as a P-Celtic or Q-Celtic. Some closely fit the concept of a tribe. Others are confederations or even unions of tribes.

- Anartes/Anartoi – Areas of modern Slovakia and modern Northern Hungary, north of the river Tysia / Tibiscus (Tisza). They lived in the eastern part of the Hercynia Silva (Hercynian Forest). Areas of modern central Slovakia and modern Northern Hungary, north of the river Tysia/Tibiscus (Tisza), north of the Teuriscii.[3] They were later assimilated by Dacians.

- Arabiates[4] - areas of modern Western Hungary and eastern Austria, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Belgites[5] - areas of modern Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Boii [2]– a tribal confederation, originally from today's Bohemia (Western Czech Republic) that dwelt in the Hercynia Silva and dispersed through migrations to other regions of Europe, to areas of modern Slovakia, Germany, Austria, Hungary and Northern Italy.[6][7][8] Another hypothesis is that they were a tribal confederation, originally from today's Southern France who migrated to Hercynia Silva under Segovesus, and dispersed through migrations to other regions of Europe, to areas of modern Slovakia, Germany, Austria, Poland and Hungary.[6][7]

- Boii tribes of unknown names in the Hercynia Silva - roughly in today's Bohemia

- Boii (in Cisalpine Gaul) – Central Emilia-Romagna (Bologna) and Lodi, Lombardy.

- Boii (in Transalpine Gaul) – Boui near Entrain[6] - They were related to or a branch of the Boii.

- Boii Boiates / Boviates / Boiates – La Tête de Buch, probably around Arcachon Bay and northwest of Landes (departement), in the Pays de Buch and Pays de Born. Although they dwelt in Aquitania Proper, they seem to have been a Celtic tribe and not a tribe of the Aquitani (a people that may have been ancestor of the Basques).

- Boii (in Pannonia) - Pannonia, today's Western Hungary (west of the Danube) and part of eastern Austria

- Tulingi (Tylangii?) – localization unclear, possibly Southern Germany, Switzerland, or Austria; an originally Boii Celtic tribe that migrated along the upper Danube and later allied with the Helvetii?; also, may have been a Germanic tribe.

- Breuci[9]

- Carni – Carnic Alps, South Austria (Carinthia/Kärnten), Western Slovenia (Carniola/Kranjska) and Northern Friuli/Friûl (Carnia/Cjargna). A tribe related to the Carnutes? Also, may have been a Venetic tribe (the Veneti were a transitional people between Celts and Italics or a Celticized Italic people).

- Catubrini - In the Alps Southeastern slopes, close to Plavis (Piave) and near Bellunum (Belluno), to the Southwest of the Carni. They came from Central Europe and not from Gaul (Gallia). (They were not Cisalpine Gaulish Celts).

- Celts of Tylis / Tylisian Celts[10]

- Cornacates[11]- areas of modern Western Hungary, west of river Danubius (Danube).

- Cotini – areas of modern Slovakia, west of the Anartes, and areas of Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube), south of Lacus Pelsodis / Pelso (today's Lake Balaton).

- Eravisci / Aravisci [12]– areas of modern Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube), Aquincum (modern Budapest) was in their territory.

- Helvetii-Rauraci / Raurici

- Helvetii – original dwellers of Agri Decumates region, in the western part of Hercynia Silva, to the east and north of the Rhine; later, possibly at the end of the 3rd century BC they expanded to the South and Southwest to land later called Helvetia (modern day Switzerland). They were possibly more related to the Celtic populations of the upper Danube basin than to the Celts of Gaul.

- Rauraci / Raurici – Kaiseraugst (Augusta Raurica), a tribe closely related to the Helvetii.

- Hercuniates / Hercuniatae[13] - areas of modern Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Latobici / Latovici[14] - not the same tribe as the Latobrigi but they could have been related, they dwelt in areas of modern Slovenia and Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Latobrigi - uncertain location, maybe to the north or northeast of the Helvetii in the upper Danube (Danubius) and upper Rhine river basins, original dwellers of Agri Decumates region, in the western part of Hercynia Silva.

- Scordisci[15] - areas of modern Serbia, Croatia, Austria, Romania, west of the river Danubius (Danube). According to Livy, they were related to the Bastarnae.

- Serdi[18][19] - in Serdica region (today's Sofiya, Bulgaria's Capital)

- Serrapilli / Serapilli - areas of modern Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Serretes[20] - areas of modern Western Hungary, west of the river Danubius (Danube).

- Tricornenses[21] (a later formation tribe)

- Norici / Taurisci / Varisci - a tribal confederation

- Alauni - in the middle Aenus river basin (Inn), east of the Aenus in the Eastern Alps, Chiemsee and Attersee lakes region.

- Ambidravi / Ambidrani - in the upper and middle Dravus (Drau/Drava) river basin in the Eastern Alps and also in the Mur/Mura river basin, today's Carinthia and Styria, Austria.

- Ambilici - in the Dravus (Drau/Drava) river basin, east of the Ambidravi/Ambidrani (today's Southeast Austria and Northeast Slovenia).

- Ambisontes / Ambisontii - in the Alpes Noricae (East Central Alps), in the upper Salzach river basin.

- Norici (Narisci) / Nori - may have been a tribe of the larger Taurisci tribal federation; in the Eastern Alps and in the Mur/Mura and Schwarza rivers basins and other areas, today's Styria and Lower Austria (Austria) south of the Danubius (Danube), also may have been a Germanic tribe.

- Sevaces - in the low Aenus river basin (Inn), east of the Aenus and south of the Danubius (Danube), roughly in today's Upper Austria.

- Teuriscii - A branch of the Celtic Taurisci (originally from Noricum) in the Tysia/Tibiscus (Tisza) river basin south of the Anartes/Anartii/Anartoi. Celts assimilated by Dacians[3]

- Varciani [14]– areas of modern Slovenia, Croatia.

- Vindelici – a tribal confederation, areas of modern Southern Germany (Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg), in the upper Danube basin. May have been a confederation of mixed Celtic and Germanic tribes.

- Brigantii – in the Lacus Brigantinus (Lake Constance) area, Brigantia (Bregenz) was the main centre, in the border areas of modern Germany, Austria and Switzerland, north of the Vennonetes/Vennones/Vennonienses.

- Catenates - South of the Danubius (Danube), in the low Licus (Lech) river area, Augusta Vindelicorum region (today's Augsburg), north of the Licates.

- Consuanetae / Cosuanetes / Cotuantii - Upper and middle valley of fl. Isarus (r. Isar) (Bavarian Alps) in today's Upper Bavaria, Germany.

- Estiones - South of the Danubius (Danube), in the Ilargus (Roth) and Riss rivers area, including today's Ulm area (between modern Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg), Cambodunum (today's Kempten) was one of their towns.

- Leuni - in the Isarus (Isar) and Ammer (Amper) river areas, Munich area, Bavaria.

- Licates -in the Licus (Lech) river valley, south of the Catenates.

- Rucinates / Rucantii - Between rivers Isarus (Isar) and Danuvius (Danube), Low Bavaria.

- Vennones / Vennonienses / Vennonetes - Upper valley of fl. Rhenus (r. Rhine) in today's canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland, south of the Brigantii.

- Vindelici Proper – a tribe to the north of the Upper Danube.

- Volcae - a tribal confederation, originally from today's Moravia (Eastern Czech Republic), Central and Upper Danube basin (Slovakia, Austria, Southern Germany), also in Main river basin, to the west of the Boii. They dwelt in Hercynia Silva, north of the Danuvius (Danube) but dispersed through migrations to other regions of Europe (Southern Gaul) and Asia Minor/Anatolia (Galatia).

- Volcae tribes of unknown names in Hercynia Silva - roughly in today's Moravia and Main river basin.

- Volcae Arecomici / Volcae Arecomisci – in southern Gaul, in the Mediterranean coast of today's Languedoc.

- Volcae Tectosages (in Southern Gaul and also in Galatia, Central Asia Minor or Anatolia, one of the main tribes that formed the Galatians)

- Possible Volcae tribes

- Volciani – may have been a tribe related to the Volcae and not to the Hispano-Celts / Iberian Celts (i.e., the Celts of the Iberian Peninsula). Located north of the river Iberus (Ebro), but not very precisely.

In the middle 3rd century BC, Celts from the middle Danube valley, immigrated from Thrace into the highlands of central Anatolia (modern Turkey), which was called Galatia after that. These people, called Galatians, a generic name for “Celts”, were eventually Hellenized,[22][23] but retained many of their own traditions. They spoke Galatian, a name derived from the generic name for “Celts”. Some closely fit the concept of a tribe. Others are confederations or even unions of tribes.

- Aigosages,[24] between Troy and Cyzicus

- Daguteni,[24] in modern Marmara region around Orhaneli

- Inovanteni,[24] east of the Trocnades

- Okondiani,[24] between Phrygia and Galatia northeast of modern Akşehir Gölü

- Rigosages,[24] unlocated

- Trocnades,[24] in Phrygia around modern Sivrihisar

- Unknown tribe (Territory of Gaezatorix, a Celtic Chieftain),[24] between Bithynia and Galatia at modern Bolu

- Core Galatians

- Tectosages,[24] in Galatia

- Tolistobogii,[24] in Galatia

- Trocmii,[24] in Galatia (easternmost known Celtic tribe)

Gauls were the Celtic people that lived in Gaul having many tribes but with some influential tribal confederations. Galli (Gauls), for the Romans, was a name synonym of “Celts” (as Julius Caesar states in De Bello Gallico[25]) which means that not all peoples and tribes called “Galli” were necessarily Gauls in a narrower regional sense. Gaulish Celts spoke Gaulish, a Continental Celtic language of the P Celtic type, a more innovative Celtic language - *kʷ > p. Romans initially organized Gaul in two provinces (later in three): Transalpine Gaul, meaning literally "Gaul on the other side of the Alps" or "Gaul across the Alps", is approximately modern Belgium, France, Switzerland, Netherlands, and Western Germany in what would become the Roman provinces of Gallia Narbonensis, Gallia Celtica (later Lugdunensis and Aquitania) and Gallia Belgica. Some closely fit the concept of a tribe. Others are confederations or even unions of tribes.

- Abrincatui - in Aremorica or Armorica

- Aedui / Haedui - Gaulish Celts largest tribal confederation, roughly in the geographical centre of Gaul and controlling important land, river, and trade routes

- Aedui / Haedui proper - Bibracte

- Ambivareti

- Parisii (Gaul) - Lutetia, today's Paris, was their capital. A tribe of similar name, the Parisi, dwelt in East Yorkshire, United Kingdom.

- Senones – Sens

- Agenisates / Angesinates – Angoumois

- Agnutes – Vendée

- Allobroges/Allobriges – Vienne, Southern Gaul

- Ambarri (they were allies to the Aedui Confederation but not part of it)

- Ambiliates / Ambilatres – Low Liger (Loire), in Aremorica or Armorica

- Ambivarii / Ambibarii - in Aremorica or Armorica

- Anagnutes

- Andecamulenses

- Andecavi/Andes – Angers

- Antobroges

- Arverni – Gergovia (tribal confederation)

- Armoricani / Aremoricii - in Aremorica or Armorica (Land "Before the Sea” or “Close to the Sea” - Are Morica)

- Arvii

- Atacini – Aussière

- Atesui

- Aulerci (tribal confederation)

- Aulerci Brannovices/Brannovii/Blannovii (a southern branch of the Aulerci but within the Aedui tribal confederation)

- Aulerci Cenomani / Gaul Cenomani – Le Mans

- Aulerci Diablintes

- Aulerci Eburovices

- Aulerci Sagii

- Baiocasses / Boiocasses – Bayeux, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Bebryces (Gauls) – in southern Gaul, south of the Volcae Arecomici, close to Narbo (Narbonne) region.

- Bipedimui / Pimpedunni

- Bituriges

- Bituriges Cubi – Bourges (an eastern branch of the Bituriges but within the Aedui tribal confederation)

- Bituriges Vivisci – Bordeaux (Burdigala)

- Cadurci – Cahors

- Caeresi

- Cambolectres

- Carnutes – Autricum (Chartres), Cenabum / Genabum (Orléans), in Aremorica or Armorica

- Chalbici – Chablais, in Southern Gaul, south of Lake Leman

- Corisopiti

- Curiosolitae / Coriosolites – Corseul, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Edenates – in Southern Gaul

- Eleuterii

- Elycoces

- Epomandui

- Esuvii / Esubii / Sesuvii

- Helvii / Elvi - Southern Gaul

- Lemovices – Limoges

- Lexovii – Lisieux, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Lingones

- Mandubii – Alesia (under Aedui Confederation influence but not part of it)

- Medulli Meduci – Médoc, southwestern Gaul

- Namnetes – Nantes, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Nantuates / Nantuatae

- Nitiobroges/Nitiobriges

- Osismii - Western end of Brittany Peninsula, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Petrocorii – Périgueux

- Pictones/Pictavi – Poitiers

- Redones – Rennes, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Ruteni – Rodez

- Santones – Saintes

- Seduni – High Rhône river valley, Sion (Middle Valais, Switzerland)

- Segusiavi / Segobriges - Lugdunum (Lyon), that was to be capital of Gallia Lugdunensis, was in their land (they were allies to the Aedui Confederation but not part of it).

- Segovellauni / Segovi – in Southern Gaul

- Sequani – Besançon

- Tornates / Turnates

- Tricasses / Tricassini

- Triviatii

- Trones

- Turones / Turoni – Tours

- Uberi / Viberi – High Rhône river valley, Upper Valais

- Vellavi / Velaunii – Ruessium

- Venelli / Unelli – Coutances, Cotentin Peninsula, in today's Western Normandy region, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Veneti – Vannes, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Viducasses / Vadicasses / Vadicassii – Vieux, in Aremorica or Armorica

- Mix of several Gaulish tribes

- Gaesatae – Numbering c. 30,000, they participated in the battle of Telamon[26] a group of mercenary Celtic warriors from several tribes of the western Alps slopes, not a tribe.

- Possible Gaulish tribes

- Galli (tribe) – along Gallicus (Gállego) river banks, see place names (toponyms) like Forum Gallorum, Gallur, a different tribe from the Suessetani; may have been a tribe related to the Galli (Gauls) and not to the Hispano-Celts / Iberian Celts. Some Gaulish tribes may have migrated southward and crossed the Pyrenees (by the north, the central, or the south areas of the mountains) in a second or a third Celtic wave to the Iberian Peninsula. These tribes were different from the Hispano-Celtic / Iberian Celtic tribes.

- Garumni – along the banks of the high Garumna (Garonne), southwest of the Volcae Tectosages, and in and around Lugdunum Convenarum, among the Convenae. Although they dwelt in Aquitania Proper, they seem to have been a Celtic tribe and not a tribe of the Aquitani (a people that may have been the ancestor of the Basques).

- Cisalpine Gauls (Celtae / Galli Cisalpini) - They lived in Cisalpine Gaul, most of today's northern Italy. Multiple waves of population movements from France.[7] They spoke Cisalpine Gaulish (a Continental Celtic language of the P Celtic type) closely related to Gaulish or Gallic. They lived in Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina), also called Gallia Citerior or Gallia Togata,[27] was the part of Italy continually inhabited by Celts since the 13th century BC.[28] Conquered by the Roman Republic in the 220s BC, it was a Roman province from c. 81 BC until 42 BC, when it was merged into Roman Italy.[29] Until that time, it was considered part of Gaul, precisely that part of Gaul on the "hither side of the Alps" (from the perspective of the Romans), as opposed to Transalpine Gaul ("on the far side of the Alps").[30]

- Seven Gaulish tribes that according to Livy settled in Cisalpine Gaul around 600 BC. Led by Bellovesus, they defeated the Etruscans at the Ticino, settled in Insubria and founded the city of Mediolanum, the modern Milan.[31] They were ancestors of Cisalpine Gauls.

- Anani – Western Emilia, Po Valley, (Fidentia, Province of Piacenza)

- Anamares – Minor tribe whose precise location along the southern bank of the river Padus in Italy is uncertain

- Anares – Middle Po Valley, Placentia (Piacenza, Province of Piacenza)

- Cenomani (Cisalpine Gaul) – Eastern Lombardy (Brixia, Cremona). Related to or a branch of the Cenomani (Aulerci Cenomani) that lived in Transalpine Gaul (Gallia Transalpina).

- Insubres – Western Lombardy (Milan). Said by Pliny to descend from the Aedui.

- Lingones – North-eastern Emilia-Romagna (Ferrara), Po Valley. Related to or a branch of the Lingones that lived in Gaul (Gallia).

- Senones – South-eastern Emilia-Romagna (Rimini) and Northern Marche (Senigallia). Related to or a branch of the Senones that lived in Gaul (Gallia).

They seem to have been an older group of Celts that lived in Cisalpine Gaul before the Gaulish Celtic migration. They spoke Lepontic (a Continental Celtic language) a Celtic language that seems to precede Cisalpine Gaulish.

- Lepontii / Lepontii / Leipontii / Lepontes – Valle Leventina and Val d'Ossola in today's Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, Piemonte, North-eastern Piedmont, far Northwestern Lombardy, and Switzerland in the Lepontine Alps. They were not Gaulish Celts

- Orobii or Orumbovii – Central Lombardy (Bergamo)

May have been Celtic tribes influenced by Ligurians, heavily Celticized Ligurian tribes that shifted to a Celtic ethnolinguistic identity or mixed Celtic-Ligurian tribes. They dwelt in southeastern Transalpine Gaul and northwestern Cisalpine Gaul, mainly in the Western Alps regions, Rhodanus eastern basin and upper Po river basin.

- Acitavones

- Adenates / Adanates – slopes of the Western Alps (Maurienne-Modanne), Southern Gaul

- Adunicates – Andon área, Southern Gaul

- Albici – Middle and Lower Durance river valley, Southern Gaul (tribal confederation)

- Albienses / Albici Proper

- Vordenses

- Vulgientes

- Anatili

- Avantices (Avantici)

- Avatices / Avatici – Camargue – Rhodanus river delta, south of the Volcae Arecomici, in Southern Gaul

- Belaci

- Bodiontici – in Southern Gaul

- Bormanni

- Bramovices – Low Tarentaise, Savoy, Southern Gaul

- Briganii / Brigianii – Briançon, High Durance river valley, Southern Gaul

- Caburri

- Camatulici

- Casmonates / Cosmonates (in the area of Castellazzo Bormida)

- Caturiges – Chorges, High Durance river valley, in Southern Gaul

- Cavares/Cavari – North of Low Durance, Arausio (Orange), in Southern Gaul (tribal confederation)

- Ceutrones / Centrones – Moûtiers, in the western Alps slopes, Southern Gaul

- Coenicenses

- Dexivates

- Esubiani – Ubaye Valley, Southern Gaul

- Euburiates

- Gabieni

- Glanici

- Graioceli / Garocelli – Alps western slopes in part of eastern Savoy, and Alps eastern slopes, northwestern Piedmont in the Graian Alps

- Iadatini

- Iconii – Gap, in Southern Gaul

- Irienses

- Libii / Libici

- Ligauni

- Maielli

- Medulli – upper valley of Maurienne, Southern Gaul

- Naburni

- Nearchi

- Nemalones / Nemolani – in Southern Gaul

- Nemeturii – High Var river valley, Southern Gaul

- Orobii - in the northern Italian Alpine valleys of Bergamo, Como and Lecco

- Quariates – in Southern Gaul

- Reieni / Reii - in Southern Gaul

- Salassi (Gallo-Ligurian people) – Aosta Valley and Canavese (Northern Piedmont) (Ivrea)

- Salyes / Salluvii

- Savincates

- Sebagini

- Segobriges

- Segovi

- Segusini - in Segusa (today's Susa, Piemonte)

- Sentienes / Sentii – Senez, in Southern Gaul

- Sigorii

- Sogiontii

- Suelteri / Sueltri

- Suetrii

- Taurini – parts of central Piedmont (Turin region)

- Tebavii

- Tricastini

- Tricorii – in Southern Gaul

- Tritolii

- Ucenni

- Veamini – in Southern Gaul

- Vennavi

- Vergunni – Vinon-sur-Verdon, Southern Gaul

- Verucini

- Vocontii / Transalpine Gaul Vertamocori – Vaison-la-Romaine, Southern Gaul (in modern Provence, on the east bank of the Rhône and Vercors, southern Gaul.

- Vertamocorii – Eastern Piedmont (Novara). Said by Pliny to descend from the Vocontii.

They lived in large parts of the Iberian Peninsula, in the Northern, Central, and Western regions (half of the Peninsula's territory). The Celts in the Iberian peninsula were traditionally thought of as living on the edge of the Celtic world of the La Tène culture that defined classical Iron Age Celts. Earlier migrations were Hallstatt in culture and later came La Tène influenced peoples. Celtic or (Indo-European) Pre-Celtic cultures and populations existed in great numbers and Iberia experienced one of the highest levels of Celtic settlement in all of Europe. They dwelt in northern, central and western regions of the Iberian Peninsula, but also in several southern regions. They spoke Celtic languages - Hispano-Celtic languages which were of the Q-Celtic type, more conservative Celtic languages. Romans initially organized the Peninsula in two provinces (later in three): Hispania Citerior ("Nearer Hispania", "Hispania that is Closer", from the perspective of the Romans), was a region of Hispania during the Roman Republic, roughly occupying the northeastern coast and the Iberus (Ebro) Valley and later the eastern, central, northern and northwestern areas of the Iberian peninsula in what would become the Tarraconensis Roman province (of what is now Spain and northern Portugal). Hispania Ulterior ("Further Hispania", "Hispania that is Beyond", from the perspective of the Romans) was a region of Hispania during the Roman Republic, roughly located in what would become the provinces of Baetica (that included the Baetis, Guadalquivir, valley of modern Spain) and extending to all of Lusitania (modern south and central Portugal, Extremadura and a small part of Salamanca province). The Roman province of Hispania included both Celtic speaking and non-Celtic speaking tribes. Some closely fit the concept of a tribe. Others are confederations or even unions of tribes.

Western Hispano-Celts were Celtic peoples and tribes that inhabited most of north and western Iberian Peninsula regions. They are often confused or taken as synonym of Celtiberians but, in fact, they were a distinct Celtic population that was most part of Iberian Peninsula Celtic populations. They spoke Gallaecian (a Continental Celtic language of the Q Celtic type, a more conservative Celtic language) which was not Celtiberian (Celtic languages of Iberian Peninsula are often lumped as Hispano-Celtic).

- Allotriges / Autrigones – East Burgos (Spain), Northwestern La Rioja (Spain) to the Atlantic Coast

- Astures – Asturias and northern León (Spain), and east of Trás os Montes (Portugal), (tribal confederation).

- Cismontani

- Amaci

- Cabruagenigi

- Gigurri

- Lancienses

- Lougei

- Orniaci

- Superatii

- Susarri/Astures Proper

- Tiburi

- Zoelae – Eastern Trás-os-Montes (Portugal), (Miranda do Douro).

- Transmontani

- Baedunienses

- Brigaentini

- Cabarci

- Iburri

- Luggones/Lungones

- Paenii

- Paesici

- Saelini

- Vinciani

- Viromenici. Might be related to the Viromandui.

- Cismontani

- Bebryaces / Berybraces – unknown location, may have been related to the Bebryces (gauls) or the Berones, there is also the possibility that it was an old name of the Celtiberians.

- Berones – La Rioja (Spain). Could have been related to the Eburones.

- Cantabri – Cantabria, part of Asturias and part of Castile and León (Spain); some consider them not Celtic, may have been Pre-Celtic Indo-European as could have been the Lusitani and Vettones [2]. If their language was not Celtic it may have been Para-Celtic like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). A Tribal confederation.

- Avarigines

- Blendii / Plentusii / Plentuisii

- Camarici / Tamarici

- Concani / Gongani – two tribes of similar name (the Britannia Gangani and Hibernia Gangani) lived in Britannia and Hibernia, they could have been three branches of the same tribe, three related tribes with common ancestors or three different tribes that shared similar names.

- Coniaci / Conisci

- Moroecani

- Noegi

- Orgenomesci

- Salaeni / Selaeni

- Vadinienses

- Vellici / Velliques

- Caristii / Carietes – today's West Basque Country, they may have been Celtic (see Late Basquisation), they were later assimilated by the Vascones in the 6th and 7th centuries CE; Some consider them not Celtic, may have been a Pre-Celtic Indo-European people as the Lusitani and Vettones could have been. [3]. If their language was not Celtic it may have been Para-Celtic like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic).

- Carpetani – Central Iberian meseta (Spain), in the geographical centre of the Iberian Peninsula, in a large part of today's Castilla-La Mancha and Madrid regions. A tribal confederation with 27 identified tribes.[32] (the name of these tribes is known today by archaeology discovery of their names in old stellae and not by mention of any known or survived works of Classical Antiquity authors)

- Aelarici / Aelariques

- Aeturici / Aeturiques

- Arquioci - in Iplacea, Roman named Complutum (today's Alcalá de Henares) region.

- Acualici / Acualiques

- Bocourici / Bocouriques

- Canbarici - in Toletum (Toledo) region.

- Contucianci - in Segobriga region.

- Dagencii

- Dovilici / Doviliques

- Duitici / Duitiques

- Duniques

- Elguismici / Elguismiques

- Langioci

- Longeidoci

- Maganici / Maganiques

- Malugenici / Malugeniques

- Manucici / Manuciques

- Maureici

- Mesici

- Metturici

- Moenicci

- Obisodici / Obisodiques - in Toletum (Toledo) region

- Pilonicori

- Solici

- Tirtalici / Tirtaliques - in Segobriga region.

- Uloci / Uloques

- Venatioci / Venatioques

- Celtici – Portugal south of the Tagus and north of Guadiana (Anas), Alentejo and Algarve (Portugal), western Extremadura (Spain), (tribal confederation).

- Celtici of Arunda (Ronda) – in south Turdetania, later Baetica Roman province, (in today's western Málaga Province), Andalusia region (southernmost known Celtic tribe).

- Cempsi

- Conii – according to some scholars, Conii and Cynetes were two different peoples or tribes and the names were not two different names of the same people or tribe; in this case, the Conii may have dwelt along the northern banks of the middle Anas (Guadiana) river, in today's western Extremadura region of Spain, and were a Celtici tribe wrongly confused with the Cynetes of Cyneticum (Algarve) that dwelt from the west banks of the Low river Anas (Guadiana) further to the south (the celticization of the Cynetes by the Celtici confused the distinction between the two peoples or tribes).[33]

- Mirobrigenses

- Saephes / Saefes / Sefes - people or tribe of the Celtici that has been identified as synonymous with the Ophi or Serpent People (their land was called Ophiussa), a people that migrated westward and conquered and expelled an older people known as the Oestrymni or Oestrimni (in a land that was called Oestriminis).

- Unknown tribes

- Gallaeci / Callaici (Gallecians) – Gallaecia (Portugal & Galicia). Western Hispano-Celts largest tribal confederation.

- Abobrigenses

- Addovi / Iadovi

- Aebocosi

- Aedui (Gallaecian tribe)

- Albiones / Albioni – western Asturias (Spain).

- Amphiloci

- Aquaflavienses / Aquiflavienses - Vila Real District (Chaves), (Portugal)

- Arroni / Arrotrebi

- Arrotrebae / Artabri (Turodes Artabri) – Northern Galicia (Spain), They might be related to the Atrebates of Gallia Belgica.

- Artodii

- Aunonenses

- Baedi

- Banienses – around Baião Municipality, Eastern Porto District, (Portugal).

- Barhantes

- Bibali / Biballi

- Bracari / Callaeci Bracari – roughly in today's Braga District, (Portugal).

- Brassii

- Brigantes (Gallaecian tribe) – Northern Bragança District, Bragança, (Portugal).

- Caladuni

- Capori / Copori

- Celtici (Gallaecian)

- Cibarci

- Cileni

- Coelerni – southwestern Ourense Province (Spain), south of Minho (river).

- Cuci

- Egi

- Egovarri / Varri Namarini

- Equaesi – Minho and Trás-os-Montes (Portugal).

- Gallaeci or Callaeci Proper, this tribe gave name to the larger tribal confederation of the same name (not the same tribe as the Bracari) - roughly in today's Porto District (Portuguese District = County) west of the Tâmega.

- Grovii / (Turodes Grovii) – Minho (Portugal) and Galicia (Spain).

- Iadones

- Interamici / Interamnici – Trás-os-Montes (Portugal).

- Lapatianci

- Lemavi

- Leuni – Minho (Portugal).

- Limici – Lima river banks, Minho (Portugal) and Galicia (Spain).

- Louguei

- Luanqui – Trás-os-Montes (Portugal).

- Naebisoci / Aebisoci

- Namarii

- Narbasi -Minho (Portugal) and Galicia (Spain).

- Nemetati – Minho (Portugal).

- Nerii / Neri

- Poemani, they might be related to the Paemani.

- Quaquerni / Querquerni – Minho (Portugal).

- Segodii

- Seurbi – Minho (Portugal).

- Seurri – Sarria Municipality, East Central Galicia (Spain)

- Tamagani – Chaves (Portugal).

- Tongobrigenses

- Turodi / Turodes – Trás-os-Montes (Portugal) and Galicia (Spain).

- Cynetes – Cyneticum (today's Algarve region) and Low Alentejo (Portugal); originally probably Tartessians or similar, later celtized by the Celtici; according to some scholars, Cynetes and Conii were two different peoples or tribes[33] [4].

- Oestrymni or Oestrimni or Oestrymini - They lived in far-western Iberian Peninsula in coastal Atlantic regions (today's Galicia and Portugal) before other Celtic peoples, their land was called Oestryminis or Oestriminis (their existence is not well proven, semi legendary people).

- Osismii (Iberian Peninsula) - people mentioned along with the Oestrymni or may have been the same people.

- Plentauri – Northwestern La Rioja (Spain).

- Turduli – Guadiana valley (Portugal) and Extremadura (Spain); may have been related to Lusitanians, Callaeci or Turdetani.

- Turduli Baetici / Turduli Baetures - Baeturia/Baeturia Turdulorum (ancient northern region of Baetica Province), south and east of the river Anas (Guadiana) and northern slope of Marianus Mons (Sierra Morena), Southern Extremadura region, Badajoz Province, Portugal Southeastern corner, East Beja District, Alentejo region.

- Turduli Bardili – Setubal Peninsula (Portugal); may have been related to Lusitanians, Callaeci or Turdetani.

- Turduli Oppidani – Estremadura and Beira Litoral (Portugal); may have been related to Lusitanians, Callaeci or Turdetani.

- Turduli Veteres – Southern Douro banks, between Douro and Vouga River, Aveiro District, (Portugal); may have been related to Lusitanians, Callaeci or Turdetani.

- Turmodigi or Turmogi - Central Burgos.

- Vaccaei – North Central Iberian meseta (Spain), middle Duero river basin. A tribal confederation. Ptolemy mentions 20 vaccaean Civitates (that also had the meaning of tribes)[34]

- Cauci (Vaccaei) – in Cauca (Coca, Segovia)

- Other tribes (19 other tribes mentioned by Ptolemy)

- Varduli – today's East Basque Country, they may have been Celtic (see Late Basquisation), they were later assimilated by the Vascones in the 6th and 7th centuries AD; Some consider them not Celtic, may have been a Pre-Celtic Indo-European people as the Lusitani and Vettones could have been. If their language was not Celtic it may have been Para-Celtic like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). [5].

Eastern Iberian meseta (Spain), mountains of the headwaters of the rivers Douro, Tagus, Guadiana (Anas), Júcar, Jalón, Jiloca and Turia, (tribal confederation). Mixed Celtic and Iberian tribes or Celtic tribes influenced by Iberians. Not synonymous of all the Celts that lived in the Iberian Peninsula but to a narrower group (the majority of Celtic tribes in the Iberian Peninsula) were not Celtiberians. They spoke Celtiberian (a Continental Celtic language of the Q Celtic type, a more conservative Celtic language).

- Arevaci (Celtiberian Arevaci – Celtiberian tribe “Before or Close to the Vaccaei” – Are Vaci – Are Vaccaei)

- Belli

- Cratistii

- Lobetani

- Lusones – Western Zaragoza (province), Eastern Guadalajara (Spain).

- Mantesani / Mentesani / Mantasani – La Mancha Plateau, Castilla-La Mancha (Spain); they were a different people from the Oretani.

- Olcades

- Oretani? – northeastern Andalusia, northwest Múrcia and southern fringes of La Mancha, (Spain), mountains of the headwaters of the Guadalquivir (ancient river Baetis); Some consider them not Celtic [6] (see Germani (Oretania)).

- Pellendones / Cerindones, in high Duero river course (Numantia) and neighboring mountains, may also have been related to the Pelendi/Belendi that dwelt in the middle of the river Sigmatis, today's Leyre.

- Titii (Celtiberian)

- Turboletae / Turboleti

- Uraci / Duraci

- Possible Celtiberian tribe

- Belendi / Pelendi – Belinum territory (Belin-Béliet), in the middle Sigmatis river (in today's Leyre) river area, south of the Bituriges Vivisci and the Boii Boiates; they may have been related to the Pellendones (a Celtiberian tribe). Although they dwelt in Aquitania Proper, they seem to have been a Celtic tribe and not a tribe of the Aquitani (a people that may have been the ancestor of the Basques).

Insular Celts were the Celtic peoples and tribes that inhabited the British Islands, Britannia (Great Britain), the main largest island to the east, and Hibernia (Ireland), the main smaller island to the west. There were three or four distinct Celtic populations in these islands, in Britannia inhabited the Britons, the Caledonians or Picts, the Belgae (not surely known if they were a Celtic people or a distinct but closely related one); in Hibernia inhabited the Hibernians or Goidels or Gaels. Britons and Caledonians or Picts spoke the P-Celtic type languages, a more innovative Celtic language (*kʷ > p) while Hibernians or Goidels or Gaels spoke Q-Celtic type languages, a more conservative Celtic language. Classical Antiquity authors did not call the British islands peoples and tribes as Celts or Galli but by the name Britons (in Britannia). They only used the name Celts or Gauls for the peoples and tribes of mainland Europe.[1]

They spoke Brittonic (an Insular Celtic language of the P Celtic type). They lived in Britannia, it was the name Romans gave, based on the name of the people: the Britanni. Some closely fit the concept of a tribe but others are confederations or even unions of tribes.

- Ancalites (mentioned by Caesar; uncertain: speculatively Hampshire and Wiltshire) (they may have been later conquered by the possibly Belgian Catuvellauni)

- Attacotti (origin uncertain)

- Bibroci (mentioned by Caesar; location uncertain but possibly Berkshire) (they may have been later conquered by the possibly Belgian Catuvellauni)

- Boresti (sometimes Horesti) (In or near Fife, Scotland according to Tacitus)

- Brigantes (an important tribe in most of Northern England and in the south-east corner of Ireland)

- Cantiaci (in present-day Kent which preserves the ancient tribal name)

- Carvetii (Cumberland)

- Cassi (mentioned by Caesar; possibly south-east England) (they may have been later conquered by the possibly Belgian Catuvellauni)

- Corieltauvi / Coritani (East Midlands including Leicester)

- Corionototae (possibly a tribe, a subtribe of the Brigantes or a group of warriors) (Northumberland)

- Cornovii (Midlands)

- Damnonii (Southwestern Scotland)

- Deceangli (Flintshire, Wales)

- Demetae (Dyfed, Wales)

- Dobunni (Cotswolds and Severn valley)

- Dumnonii (Devon, Cornwall, Somerset)

- Cornovii (Cornwall) (a sub-tribe of the Dumnonii)

- Durotriges (Dorset, south Somerset, south Wiltshire, possibly the Isle of Wight

- Gabrantovices (North Yorkshire)

- Gangani (Llŷn Peninsula, Wales) - A tribe of the same name, the Gangani (Ganganoi), lived in Hibernia's southwestern coast, they could have been two branches of the same tribe, two related tribes with common ancestors or two different tribes that shared similar names. A tribe of similar name, the Gongani or Concani, was a tribe of the Cantabri, they could have been another branch of the same tribe, related tribes with common ancestors or a different tribe that shared a similar name.

- Iceni-Cenimagni (may have been the same tribe)

- Cenimagni (Iceni Magni?) (mentioned by Caesar; perhaps the same as the Iceni)

- Iceni (East Anglia) – under Boudica, they rebelled against Roman rule

- Novantae (Galloway and Carrick)

- Ordovices (Gwynedd, Wales) – they waged guerrilla warfare from the north Wales hills

- Parisi (East Riding of Yorkshire). A tribe of similar name, the Parisii, dwelt in Paris region, France.

- Segontiaci (mentioned by Caesar; probably south-east England) (they may have been later conquered by the possibly Belgian Catuvellauni)

- Selgovae (Dumfriesshire and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright)

- Setantii (possibly a tribe) (Lancashire)

- Silures (south Wales) – resisted the Romans in present-day south Wales

- Trinovantes / Trinobantes (Essex) – neighbours of the Iceni, they joined in their rebellion

- Votadini / Otadini (north-east England and south-east Scotland) – they later formed Gododdin

Picts / Caledonians

[edit]

They were a different people from the Britons [citation needed], but may have shared common ancestry. They lived as a tribal confederation in Caledonia (today's Northern Scotland); the Caledonian Forest (Caledonia Silva) was in their land.

- Caledonians / Caledones - a tribal confederation

- Carnonacae (western Highlands)

- Carini or Caereni (far western Highlands)

- Cateni (north and west of Sutherland) – they gave the county its Gaelic name Cataibh

- Cornovii/Cornavii (far northern mainland Scotland) (northernmost known Celtic tribe)

- Creones (Argyll)

- Decantae or Ducantae (eastern Ross and Black Isle)

- Epidii (Kintyre and neighboring islands)

- Lugi (southern Sutherland)

- Maeatae / Maetae (Miathi?)

- Smertae (central Sutherland)

- Tribe of unknown name in the Faroe Islands (may have been Picts)

- Tribe of unknown name in the Orkney Islands (may have been Picts)

- Tribe of unknown name in the Shetland Islands (may have been Picts)

Goidels / Gaels / Hibernians

[edit]

They spoke Goidelic (an Insular Celtic language of the Q Celtic type. According to Ptolemy's Geography (2nd century AD) (in brackets the names are in Greek as on the map):

- Autini (Aouteinoi - Auteinoi on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Brigantes (Britons? A tribe of the same name lived in northern Britannia or they could have been two different tribes that shared the same name)

- Cauci (Καῦκοι, Kaukoi on the map) A tribe of the same name (Chauci) lived in Northern Germany or they could have been two different tribes that shared the same name.

- Coriondi (or Koriondoi) A tribe of a similar name (Corionototae) lived in Northern Britannia.

- Darini (Darinoi)

- Eblani (Eblanioi)

- Erdini (Erdinoi)

- Gangani (Ganganoi) (Britons? A tribe of the same name lived in western Britannia (today's northwestern Wales) they could have been two branches of the same tribe, two related tribes with common ancestors or two different tribes that shared similar names.

- Iverni (Iouernoi - Iwernoi on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Manapii (Manapioi) (Belgae? A tribe of similar name, the Menapii, lived in the coast of Belgica province or they could have been two different tribes that shared similar names)

- Nagnatae or Magnatae (Nagnatai or Magnatai)

- Robogdii (Rhobogdioi)

- Usdiae (Ousdiai - Usdiai on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Uterni (Outernoi - Uternoi on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Velabri or Vellabori (Ouellaboroi - Wellabrioi on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Vennicnii (Ouenniknioi - Wenniknioi on the map, not the Greek spelling)

- Volunti (Ouolountioi - Woluntioi on the map, not the Greek spelling) – identifiable with the Ulaidh/Uluti[35]

- Later peoples

- Scotti (western portion of Scotland, later they expanded for most part of the country) - a later people from late Classical antiquity and early Middle Ages, descendant from ancient North Ireland tribes (mostly from the Darini, Robogdii and Volunti / Uluti) that crossed the North Channel, they formed the kingdoms of Ulaid and Dál Riata.

Possible Para-Celts

[edit]Para-Celtic has the meaning that these peoples had common ancestors with the Celts but were not Celts themselves (although they were later Celticized and belong to a Celtic culture sphere of influence), they were not direct descendants from the Proto-Celts. They may in fact have been Proto-Celto-Italic, predating the Celtic or Italic languages and originated earlier from either Proto-Celtic or Proto-Italic populations who spread from Central Europe into Western Europe after new Yamnaya migrations into the Danube Valley.[36] Alternatively, a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European" and associated with the Beaker culture, may have been ancestral to not only Celtic and Italic, but also to Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[36]

Source:[37]

A people or a group of related tribes that dwelt in Belgica, parts of Britannia, and may have dwelt in parts of Hibernia and also parts of Hispania (large tribal confederation). According to classical authors works, like Caesar's De Bello Gallico,[25] they were a different people and spoke a different language (Ancient Belgic) from the Gauls and Britons; they were clearly an Indo-European people and may have spoken a Celtic language. There is also the possibility that their language may have been a different language branch of Indo-European from the Nordwestblock culture, which may have been intermediary between Germanic and Celtic, and might have been affiliated to Italic (according to a Maurits Gysseling hypothesis).

- Mainlander Belgae (in Belgica)

- Ambiani – Amiens

- Ambivareti

- Atrebates (in Belgica) – Arras

- Bellovaci – Beauvais

- Caleti/Caletes – Harfleur (Caracotinum), later Lillebonne (Juliobona)

- Catalauni / Gaul Catuvellauni – Châlons-en-Champagne

- Catuslogi

- Eburones (mixed Belgae and Germani cisrhenani people)

- Leuci – Toul (Tullum Leucorum)

- Mediomatrici – Metz

- Meldi – Marne (Matrona) – Meaux

- Menapii – Cassel. A tribe of similar name, the Manapii (Manapioi), lived in southeastern Hibernia (modern Ireland) coast, they could have been two branches of the same tribe, two related tribes with common ancestors or two different tribes that shared similar names.

- Morini – Boulogne-sur-Mer

- Nervii – Bavay, Belgae largest tribal confederation.

- Remi – Reims

- Silvanectii – Senlis

- Suessiones – Soissons (Suessetani may have been related, result of a migration towards south)[38]

- Tencteri – Rhine east bank, may have been a Celtic tribe (and not a Germanic one) or a mixed Belgae and Germani tribe.

- Treveri – Trier

- Usipetes – Rhine east bank, may have been a Celtic tribe (and not a Germanic one) or a mixed Belgae and Germani tribe.

- Veliocasses/Velicasses/Velocasses – Rouen

- Viromandui – Noyon

- Islander Belgae (in south and southeast Great Britain)

- Atrebates (in Britannia) – an important Belgic tribe of today's Southern England, in Berkshire. Related to or a branch of the Atrebates that lived in Gallia Belgica.

- Belgae (tribe) (in Britannia) – Belgic tribe, in today's England's south coast, Isle of Wight, Hampshire, Wiltshire

- Catuvellauni (Britannia, today's Hertfordshire) – Belgic tribe, neighbours of the Iceni, they joined in their rebellion. May have been related to the Catalauni. May have conquered and assimilated the Ancalites, Bibroci, Cassi, part of the Iceni (Cenimagni) and the Segontiaci, which were Brittonic or British tribes (Insular Celts).

- Regni / Regnenses – Belgic tribe, in today's East Hampshire, Sussex and Surrey

- Possible Belgae tribe

- Suessetani - Far North Western Aragon and Far South Eastern Navarra (Spain), between the rivers Gallicus (Gállego) and Low Aragon, and between the river Ebro and Sierra de Santo Domingo mountains. Alba (Arba) river basin (a tributary of the Ebro) was in the centre of their territory that also included the Bardenas Reales. Corbio was their capital. They were north of the Celtiberians, south of the Iacetani and the Vascones, west of the Galli (tribe). They were later conquered by the Vascones in the 2nd Century B.C. which were allies of the Romans. Could have been related to the Suessiones (a tribe of the Belgae).[38]

Northern Mediterranean Coast straddling South-east French and North-west Italian coasts, including far Northern and Northwestern Tuscany and Corsica. Because of the strong Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were known already in antiquity as Celto-Ligurians (in Greek Κελτολίγυες, Keltolígues).[39] Very little is known about this language, Ligurian (mainly place names and personal names remain) which is generally believed to have been Celtic or Para-Celtic;[40][41] (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). They spoke ancient Ligurian.

- Alpini / Montani

- Apuani – Eastern Liguria from the Northern Apennines Mountains to the Mediterranean coast.

- Bagienni (or Vagienni) – (in the area of Bene Vagienna)

- Bimbelli

- Briniates (or Boactes) – (in the area of Brugnato)

- Celelates

- Cerdiciates

- Commoni

- Cosmonates

- Deciates – (a tribe that dwelt in the region of Antipolis (Antibes) west of the river Varus (Var), in modern Provence)

- Epanterii

- Euburiates

- Friniates – (in the area now called Frignano)

- Garuli – (in the area of Cenisola)

- Genuates – (in the area of Genua - Genoa)

- Hercates

- Ilvates (or Iluates) – (if different from the Iriates) (on the island of Elba)

- Iriates / Ilvates / Mainland Ilvates (Iluates?)

- Ingauni – Western Liguria from the Northern Apennines Mountains and Ligurian Alps to the Mediterranean coast.

- Intemelii - Western Liguria from the Ligurian Alps to the Mediterranean coast, west of the Ingauni, in the Albium Intemelium area (today's Ventimiglia).

- Laevi – a Ligurian tribe that dwelt in the low river Ticinus (Ticino), according to both Livy & Pliny.[42] According to Livy (v. 34), they took part in the expedition of Bellovesus into Italy in the 6th century BC

- Langates

- Lapicini (or Lapicinii) – In the extreme northern regions of Liguria, as it was defined in Roman times, on a tributary of the Magra

- Libici / Libui – Between the rivers Duria Bautica/Duria Maior (Dora Baltea) and Sesites/Sessites (Sesia).

- Magelli

- Marici – (near the confluence of the rivers Orba, Bormida and Tanaro)

- Olivari

- Oxybii - a Ligurian tribe that dwelt on the Mediterranean coast between Massalia (Marseille) and Antipolis.

- Sabates

- Segusini (or Cottii) – Western Piedmont on Cottian Alps (Susa)

- Statielli / Statiellates – on the road from Vada Sabatia, near Savona to Dertona (Tortona) and Placentia

- Sueltri / Suelteri

- Tigulli – from the Northern Apennines Mountains to the Mediterranean coast, west of the Apuani.

- Tricastini

- Vediantii

- Veiturii

- Veleiates / Veliates

- Veneni

- Possible Ligurian tribes

- Corsi

- Belatones (Belatoni)

- Cervini

- Cilebenses (Cilibensi)

- Corsi Proper

- Cumanenses (Cumanesi)

- Lestricones / Lestrigones (Lestriconi / Lestrigoni)

- Licinini

- Longonenses (Longonensi)

- Macrini

- Opini

- Subasani

- Sumbri

- Tarabeni

- Tibulati

- Titiani

- Venacini

- Corsi

- Lusitanians (Lusitani/Bellitani) – Portugal south of the Douro and north of the Tagus, and northwestern Extremadura (Spain). They spoke Lusitanian, a now extinct language which was clearly Indo-European but the kinship of it as a Celtic language is not surely proven (although many tribal names and place names, toponyms, are Celtic). Attempts to classify the language have also pointed at an Italic origin[36] or some kinship to the Nordwestblock culture language (Ancient Belgian).[36] Hence Lusitanian language may have been a Para-Celtic Indo-European branch, like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). The Lusitanians have also been identified as being a pre-Celtic Indo-European speaking culture of the Iberian Peninsula closely related to the neighbouring Vettones tribal confederation.[33] However, under their controversial theory of Celtic originating in Iberia, John T Koch and Barry Cunliffe have proposed a para-Celtic identity for the Lusitanian language and culture or that they spoke an archaic Proto-Celtic language and were Proto-Celtic in ethnicity.

- Arabrigenses

- Aravi

- Coelarni/Colarni

- Interamnienses

- Lancienses

- Meidubrigenses

- Paesuri – Douro and Vouga (Portugal).

- Palanti

- Talures

- Tangi

- Elbocori

- Igaeditani

- Tapori/Tapoli – river Tagus, around the border area of Portugal and Spain.

- Veaminicori

- Other Lusitanian tribes? (According to some scholars, these tribes were Lusitanians and not Vettones)[33]

- Vettones – Ávila and Salamanca (Spain), may have been a Pre-Celtic Indo-European people, closely related to the Lusitani. If their language was not Celtic it may have been Para-Celtic like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). A tribal confederation.

- Bletonesii – Bletisama (today's Ledesma) was their main centre, Salamanca Province, Spain.

- Other Vettonian tribes? (According to some scholars, these tribes were Lusitanians and not Vettones)[33]

Today's Western Andalusia (Hispania Baetica), Baetis (Guadalquivir) river valley and basin, Marianus Mons (Sierra Morena), some consider them Celtic,[43] may have been Pre-Celtic Indo-European people as the Lusitani and Vettones. If their language, called Turdetanian or Tartessian, was not Celtic it may have been Para-Celtic like Ligurian (i.e. an Indo-European language branch not Celtic but more closely related to Celtic). Also may have been a non-Indo-European people related to the Iberians, but not the same people. A tribal confederation but with much more centralized power, may have formed an early form of Kingdom or a Proto-civilisation (see Tartessos)

- Cilbiceni – approximately in today's Cádiz Province

- Elbisini / Eloesti / Olbisini – in today's Huelva Province

- Etmanei – in the middle area of Baetis (Guadalquivir) river course and surrounding region, approximately in today's Córdoba Province

- Gletes / Galetes / Ileates – in Marianus Mons (Sierra Morena), approximately in today's northern areas of the provinces of Huelva, Seville and Córdoba

- Turdetani / Tartessii Proper – in the low course of the river Baetis (which they called Rherkēs or Kertis)[44] (Guadalquivir) and surrounding region, approximately in today's Seville Province

Transitional people between Celts and Italics? Celticized Italic people? Para-Celtic people?

Possible Celts mixed with other peoples

[edit]- Germani Cisrhenani / Tungri (etymologies of the tribes names were Celtic; Belgic people? Chiefs anthroponyms were also Celtic) Celts influenced by Germanics or the opposite? The name Germani for ancient authors such as Julius Caesar did not always had an accurate ethnic or linguistic meaning, they were not necessarily Germanic-speaking. (a collective name for 7 tribes)

- Lugii – north and northeast of the Boii and Volcae, areas of modern far southwestern and far southern Poland; also may have been a Germanic tribe.

- Tencteri? (name etymology is Celtic)

- Usipetes?

- Bastarnae,[46][47] a Celto-Germanic people, and according to Livy "the bravest nation on earth". Possibly originating in Galicia (Eastern Europe) from the interaction between Celts, Germanics and Sarmatian Iranian peoples.

- Elisyces / Helisyces - a tribe that dwelt in the region of Narbo (Narbonne) and modern northern Roussillon. May have been either Iberian or Ligurian or a Celto-Ligurian-Iberian tribe.

Non-Celtic people, heavily Celticized

[edit]

They lived in the Central Alps, eastern parts of present-day Switzerland, the Tyrol in Austria, and the Alpine regions of northern Italy. They spoke the Rhaetian language. There is evidence that much of the non-Celtic (and Pre-Indo-European) elements (see Tyrsenian languages) of their territory had, by the time of Augustus, been assimilated to varying degrees by the influx of Celtic tribes and had adopted Celtic speech.[51] In addition, the abundance of Celtic toponyms leads to the conclusion that, by the time of Roman conquest, the Rhaetians were significantly Celticized.[52][better source needed]

- Benlauni - Upper valley of fl. Aenus (r. Inn) in today's North Tirol, Austria, along with the Breuni (may have been older dwellers than the Breuni), not the same as the Breuni, Pons Aeni (modern Wasserburg) was their main centre.

- Breuni / Brenni/Breones - Upper valley of fl. Aenus (r. Inn) in today's North Tirol, Austria, and Val Bregna and around Brenner Mountain; also may have been an Illyrian tribe and not a Rhaetian one.

- Brixenetes / Brixentes / Brixantae - Upper valley of fl. Athesis (r. Adige) in today's South Tirol, Italy, around Bressanone/Brixen.

- Calucones / Culicones - Calanda (upper valley of fl. Rhenus - r. Rhine) in today's Grisons canton, Switzerland and Valtellina, Colico.

- Camunni / Camuni - Val Camonica (river Oglio) in today's Brescia Province (Lombardia, Italy); also may have been a tribe of the Euganei and not a Rhaetian tribe. *Camunni – in the Valcamonica and Valtellina valleys of the Central Alps. A celticized Rhaetic tribe. Some consider them to be Celtic.[53]

- Consuanetae / Cosuanetes/Cotuantii? - Upper and middle valley of fl. Isarus (r. Isar) (Bavarian Alps) in today's Upper Bavaria, Germany; also may have been a tribe of the Vindelici (a tribal confederacy), named Cotuantii (if they are the same).

- Focunates - Upper valley of fl. Aenus (r. Inn) in today's North Tirol, Austria, neighbours to Genaunes and Breuni.

- Genaunes / Genauni - Upper valleys of the fl. Aenus (r. Inn) and the Athesis (Adige) in today's Tirol (North Tirol and South Tirol); also may have been an Illyrian tribe and not a Rhaetian one; east of the Lepontii.

- Isarci - Valley of fl. Isarcus (r. Isarco) in today's South Tirol, Italy.

- Medoaci - close to the Meduacum (Brenta) source, Ausugum (Borgo Valsugana) was their main town.

- Mesiales - south of the Lepontii.

- Naunes - in Val di Non, Trento Province.

- Querquani - in Quero area (today's Belluno Province, Veneto Region).

- Rucinates / Rucantii? - Between rivers Isarus (Isar) and Danuvius (Danube), Low Bavaria; also may have been a tribe of the Vindelici (a tribal confederation).

- Rugusci / Ruigusci/Rucantii? Upper Engadin (fl. Aenus - r. Inn) in today's Grisons canton, Switzerland.

- Suanetes / Suanitae / Sarunetes - Upper Rhenus (Upper Rhine) and Valley of r. Albula in today's Grisons canton, Switzerland.

- Tridentini - in the middle Athesis (Adige) river basin.

- Trumpilini / Trumplini - Val Trompia in today's Brescia Province, Italy; also may have been a tribe of the Euganei and not a Rhaetian tribe.

- Vennonetes / Vennones / Vennonienses - Upper valley of fl. Rhenus (r. Rhine) in today's canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland; also may not have been a Rhaetian tribe but instead a tribe of the Vindelici (a tribal confederation).

- Venostes - Vinschgau (It. Val Venosta) (fl. Athesis - r. Adige) in today's South Tirol, Italy.

See also

[edit]- The summary table on Celtic tribes (in French)

- Celtic peoples

- Irish clans

- Scottish clan

- Celticization

- Late Basquisation

- Illyrians

- Thracians

- Britannia

- Caledonia

- Hibernia

- Scotia

- Hispania

- List of Germanic peoples

- Iberia

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7524-2913-7

- ^ a b Mallory, J.P.; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5

- ^ a b Ioana A. Oltean, Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization, ISBN 0-415-41252-8, 2007, p. 47.

- ^ Andrea Faber, Körpergräber des 1.-3. Jahrhunderts in der römischen Welt: internationales Kolloquium, Frankfurt am Main, 19.-20. November 2004, ISBN 3-88270-501-9, p. 144.

- ^ Géza Alföldy, Noricum, Tome 3 of History of the Provinces of the Roman Empire, 1974, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 224–225. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ a b c "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 5, chapter 34". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- ^ A. Mocsy and S. Frere, Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. p. 14.

- ^ Pannonia. A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. p. 14.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank, Polybius, Rome and the Hellenistic World: Essays and Reflections, ISBN 0-521-81208-9, 2002, p. 116: "... in A7P 60 (1939) 452 8, is not Antigonus Doson but barbarians from the mainland (either Thracians or Gauls from Tylis) (cf. Rostovizef and Welles (1940) 207-8, Rostovizef (1941) 111, 1645), nor has that inscription anything to do with the Cavan expedition. On ..."

- ^ Velika Dautova-Ruševljan and Miroslav Vujović, Rimska vojska u Sremu, 2006, p. 131: "extended as far as Ruma whence continued the territory of another community named after the Celtic tribe of Cornacates"

- ^ Ion Grumeza, Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe, ISBN 0-7618-4465-1, 2009, p. 51: "In a short time the Dacians imposed their conditions on the Anerati, Boii, Eravisci, Pannoni, Scordisci,"

- ^ John T. Koch, Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, 2006, p. 907.

- ^ a b J. J. Wilkes, The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 81: "In Roman Pannonia the Latobici and Varciani who dwelt east of the Venetic Catari in the upper Sava valley were Celtic but the Colapiani of ..."

- ^ J. J. Wilkes, The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 140: "... Autariatae at the expense of the Triballi until, as Strabo remarks, they in their turn were overcome by the Celtic Scordisci in the early third century"

- ^ a b J. J. Wilkes, The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 217.

- ^ Population and economy of the eastern part of the Roman province of Dalmatia, 2002, ISBN 1-84171-440-2, p. 24: "the Dindari were a branch of the Scordisci"

- ^ John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond, The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC, ISBN 0-521-22717-8, 1992, p. 600: "In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long been supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin"

- ^ Dio Cassius, Earnest Cary, and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Vol. IX, Books 71–80 (Loeb Classical Library, No. 177), 1927, Index: "... 9, 337, 353 Seras, philosopher, condemned to death, 8. 361 Serdi, Thracian tribe defeated by M. Crassus, 6. 73 Seretium,""

- ^ Dubravka Balen-Letunič, 40 godina arheoloških istraživanja u sjeverozapadnoj Hrvatskoj, 1986, p. 52: "and the Celtic Serretes"

- ^ Alan Bowman, Edward Champlin, and Andrew Lintott, The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 10: The Augustan Empire, 43 BC-AD 69, 1996, p. 580: "... 580 I3h. DANUBIAN AND BALKAN PROVINCES Tricornenses of Tricornium (Ritopek) replaced the Celegeri, the Picensii of Pincum ..."

- ^ William M. Ramsay, Historical Commentary on Galatians, 1997, p. 302: "... these adaptable Celts were Hellenized early. The term Gallograecia, compared with Themistius' (p. 360) Γαλατία ..."

- ^ Roger D. Woodard, The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor, 2008, p. 72: "... The Phrygian elite (like the Galatian) was quickly Hellenized linguistically; the Phrygian tongue was devalued and found refuge only ..."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Prifysgol Cymru, University of Wales, A Detailed Map of Celtic Settlements in Galatia, Celtic Names and La Tène Material in Anatolia, the Eastern Balkans, and the Pontic Steppes.

- ^ a b Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Book I, chapter 1

- ^ Plutarch, Marcellus, chapters 6-7 [1]

- ^ von Hefner, Joseph (1837). Geographie des Transalpinischen Galliens. Munich.

- ^ Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei celti. La nascita, l'affermazione e la decadenza, Newton & Compton, 2003, ISBN 88-8289-851-2, ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9

- ^ Long, George (1866). Decline of the Roman republic: Volume 2. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Snith, William George (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography: Vol.1. Boston.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Titus, Livius. Ab Urbe Condita. p. 5,34.

- ^ Aguña, Julián Hurtado (2003). "Las gentilidades presentes en los testimonios epigráficos procedentes de la Meseta meridional". Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: Bsaa (69): 185–206.

- ^ a b c d e Jorge de Alarcão, “Novas perspectivas sobre os Lusitanos (e outros mundos)”, in Revista portuguesa de Arqueologia, vol. IV, n° 2, 2001, p. 312 e segs.

- ^ Ptolemy, Geographia, II, 5, 6

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Ireland, B. Lalor and F. McCourt editors, © 2003 New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 1089 ISBN 0-300-09442-6, noting that Ulaidh was the original tribal designation of the Uluti, who are identifiable as the Voluntii of the Ptolomey map and who occupied, at start, all of the historic province of Ulster.

- ^ a b c d Indoeuropeos y no Indoeuropeos en la Hispania Prerromana, Salamanca: Universidad, 2000

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 198–200. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ a b Mountain, Harry. (1997). The Celtic Encyclopedia p.225 ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1)

- ^ Baldi, Philip (2002). The Foundations of Latin. Walter de Gruyter. p. 112. ISBN 978-3-11-080711-0.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas, ed. (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 54. ISBN 978-0500015247.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas, ed. (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55. ISBN 978-0500015247.

- ^ (Liv. v. 35; Plin. iii. 17. s. 21.)

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 198–200. ISBN 1-85109-440-7, ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. ^ Jump up to: a b Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 224–225. ISBN 1-85109-440-7, ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ^ Smith, William. "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), BAETIS". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Perseus Digital Library.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ The Osi's categorization as Celtic is disputed; see Osi; also may have been a Dacian or Germanic tribe.

- ^ Adrian Goldsworthy, How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower, ISBN 0-300-13719-2, 2009, p. 105: "... who had moved to the Hungarian Plain. Another tribe, the Bastarnae, may or may not have been Germanic. ..."

- ^ Christopher Webber and Angus McBride, The Thracians 700 BC-AD 46 (Men-at-Arms), ISBN 1-84176-329-2, 2001, p. 12: "... never got near the main body of Roman infantry. The Bastarnae (either Celts or Germans), and `the bravest nation on earth' – Livy ..."

- ^ Charles Anthon, A Classical Dictionary: Containing The Principal Proper Names Mentioned In Ancient Authors, Part One, 2005, p. 539: "... Tor, " elevated," " a mountain. (Strabo, 293)"; "the Iapodes (Strabo, 313), a Gallo-Illyrian race occupying the valleys of ..."

- ^ J. J. Wilkes, The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 79: "along with the evidence of name formulae, a Venetic element among the Japodes. A group of names identified by Alföldy as of Celtic origin: Ammida, Andes, Iaritus, Matera, Maxa,"

- ^ J. J. Wilkes, Dalmatia, Tome 2 of History of the Provinces of the Roman Empire, 1969, pp. 154 and 482.

- ^ Géza Alföldy, Noricum, Tome 3 of History of the Provinces of the Roman Empire, 1974, p. 24-5.

- ^ Cowles Prichard, James (1841). Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind: 3, Volume 1. Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper. p. 240.

- ^ Markey, Thomas (2008). Shared Symbolics, Genre Diffusion, Token Perception and Late Literacy in North-Western Europe. NOWELE.

References

[edit]- Alberro, Manuel and Arnold, Bettina (eds.), e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Volume 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula, University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, Center for Celtic Studies, 2005.

- Haywood, John. (2001). Atlas of the Celtic World. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500051097 ISBN 978-0500051092

- Kruta, Venceslas. (2000). Les Celtes, Histoire et Dictionnaire. Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, coll. « Bouquins ». ISBN 2-7028-6261-6.

- Mallory, J.P. and Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Sims-Williams, Patrick. "The location of the Celts according to Hecataeus, Herodotus, and other Greek writers". In: Études Celtiques, vol. 42, 2016. pp. 7–32. [DOI:https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2016.2467]; [www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2016_num_42_1_2467]

External links

[edit]- https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/ - electronic Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by the Center for Celtic Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/home.html – 51 complete works of authors from Classical Antiquity (Greek and Roman).

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Caesar/Gallic_War/home.html – Julius Caesar text of De Bello Gallico (Gallic War).

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Caesar/Spanish_War/home.html – Unknown author text (about Julius Caesar in Hispania) of De Bello Hispaniensi (Spanish War).

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Pliny_the_Elder/home.html – Pliny the Elder text of Naturalis Historia (Natural History) – books 3–6 (Geography and Ethnography).

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/home.html – Strabo's text of De Geographica (The Geography).

KSF

KSF