List of largest exoplanets

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 116 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 116 min

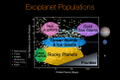

Below is a list of the largest exoplanets so far discovered, in terms of physical size, ordered by radius.

Limitations

[edit]This list of extrasolar objects may and will change over time due to diverging measurements published between scientific journals, varying methods used to examine these objects, and the notably difficult task of discovering extrasolar objects in general. These objects are not stars, and are quite small on a universal or even stellar scale. Furthermore, these objects might be brown dwarfs, sub-brown dwarfs, or not even exist at all. Because of this, this list only cites the most certain measurements to date and is prone to change.

Maximum mass limitation

[edit]Different space organisations have different maximum masses for exoplanets. The NASA Exoplanet Archive (NASA EA) states that an object with a minimum mass lower than 30 MJ, not being a free-floating object, is qualified as an exoplanet.[5] On the other hand, the official working definition by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) allows only exoplanets with a maximum mass of 13 MJ, that are orbiting a host object at a mass ratio of less than 0.04.[6][7] For the purpose of the comparison of large planets, this article includes several of those listed by NASA EA up to the maximum 30 MJ with possible brown dwarfs among them of ≳ 13 MJ as stated by IAU.[8]

Classification of Sub-brown Dwarf and Rogue Objects

[edit]Sub-brown dwarfs are formed in the manner of stars, through the collapse of a gas cloud (perhaps with the help of photo-erosion) but that has a planetary mass, therefore by definition below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (~ 13 MJ).[7] However, there is no consensus amongst astronomers on whether the formation process should be taken into account when classifying an object as a planet.[9] Free-floating sub-brown dwarfs can be observationally indistinguishable from rogue planets, which originally formed around a star and were ejected from orbit. Similarly, a sub-brown dwarf formed free-floating in a star cluster may be captured into orbit around a star, making distinguishing sub-brown dwarfs and large planets also difficult. A definition for the term "sub-brown dwarf" was put forward by the IAU Working Group on Extra-Solar Planets (IAU WGESP), which defined it as a free-floating body found in young star clusters below the lower mass cut-off of brown dwarfs.[10]

List

[edit]The sizes are listed in units of Jupiter radii (RJ, 71 492 km). This list is designed to include all exoplanets that are larger than 1.6 times the size of Jupiter. Some well-known exoplanets that are smaller than 1.6 RJ (17.93 R🜨 or 114387 km) and are gas giant have been included for the sake of comparison.

For the exoplanets with uncertain radii that could be below or above the adopted cut-off of 1.6 RJ, see the list of exoplanets with uncertain radii.

| * | Probably brown dwarfs (≳ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

|---|---|

| † | Probably sub-brown dwarfs (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass and location) |

| ? | Status uncertain (inconsistency in age or mass of planetary system) |

| ! | Uncertain status while probably brown dwarfs (≳ 13 MJ) |

| ‽ | Uncertain status while probably sub-brown dwarfs (≲ 13 MJ) |

| ← | Probably exoplanets (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

| → | Planets with grazing transit, hindering radius determination |

| # | Notable non-exoplanets reported for reference |

| – | Theoretical planet size restrictions |

| Artist's impression | |

|---|---|

| Artist's size comparison | |

| Artist's impression size comparison | |

| Direct imaging telescopic observation | |

| Direct image size comparison | |

| Composite image of direct observations | |

| Transiting telescopic observation | |

| Rendered image | |

| Orbit size comparison | |

| Illustration | Name (Alternates) |

Radius (RJ) |

Key | Mass (MJ) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sun (Sol) |

9.731 (1 R☉)[11] (695 700 km)[a] |

# | 1047.569 (1 M☉)[11] (1.988 416 × 1030 kg)[b] |

The only star in the Solar System. Responsible for life on Earth and keeping the planets on orbit. Age: 4.6 Gyr.[16] Reported for reference. |

|

Toliman (Toliman Centauri, Alpha Centauri B) |

8.360 ± 0.035[17] (0.8591 ± 0.0036 R☉) |

# | 952.450 ± 2.619[17] (0.9092 ± 0.0025 M☉) |

One of first two stars (other being Rigil Kentaurus / Alpha Centauri A) to have its stellar parallax measured.[18] Nearest (inner) binary star system and nearest star system to the Sun at the distance of 4.344 ± 0.002 ly (1.33188 ± 0.00061 pc). A member of Alpha Centauri System, the nearest system to the Sun. Age: 5.3 ± 0.3 Gyr.[19] Reported for reference. |

|

Maximum size of planetary-mass object | 8[20] | – | ~ 5[20] | Maximum theoretical size limit assumed for a ~ 5 MJ mass object right after formation, however, for 'arbitrary initial conditions'. |

|

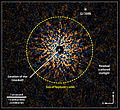

Proplyd 133-353 | ≲ 7.82 ± 0.81[21][c] (≲ 0.804 ± 0.083 R☉) |

† | (≲) 13[21] | A candidate sub-brown dwarf or rogue planet with a photoevaporating disk, located in the Orion Nebula Cluster. At a probable age younger than 500 000 years, it is one of the youngest free-floating planetary-mass candidates known.[21] More information about Proplyd 133-353 and estimates of its radius are available:[h] |

|

2M0535-05 A (V2384 Orionis A) |

6.71 ± 0.11[22] (0.690 ± 0.011 R☉) |

# | 59.9 ± 3.5[22] (0.0572 ± 0.0033 M☉) |

First eclipsing binary brown dwarf system to be discovered, orbiting around 9.8 days.[23][24] Age: ~1 Myr[25] Reported for reference. |

| 2M0535-05 B (V2384 Orionis B) |

5.25 ± 0.09[22] (0.540 ± 0.009 R☉) |

# | 38.3 ± 2.3[22] (0.0366 ± 0.0022 M☉) | ||

| KPNO-Tau-4 | 4.1[26][27] | † | 10.5[26] | A member of Taurus-Auriga star-forming region.[27] | |

| Cha J1110-7633 | 3.8[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

GQ Lupi b (GQ Lupi Ab, GQ Lupi B) |

3.70[29] | * | 20 ± 10;[29] ~ 20 (1 – 39)[30] |

First confirmed exoplanet candidate to be directly imaged. It is believed to be several times more massive than Jupiter. Because the theoretical models which are used to predict planetary masses for objects in young star systems like GQ Lupi b are still tentative, the mass cannot be precisely determined, giving the masses of 1 – 39 MJ;[30] in the higher half of this range, it may be classified as a young brown dwarf. It should not be confused with the star GQ Lup C (2MASS J15491331), 2400 AU away, sometimes referred to as GQ Lup B.[31] Other sources of the radius include 3.7 ± 0.7 RJ,[32] 3.0 ± 0.5 RJ,[30] 3.77 RJ,[33] 3.5 +1.50 −1.03 RJ,[34] 4.6 ± 1.4 RJ, 6.5 ± 2.0 RJ.[35] |

|

2M1207 (TWA 27) |

3.41[36] | * | 19.9 ± 6.3[36] | Host object of the first planetary body in an orbit discovered via direct imaging. |

|

HD 100546 b (KR Muscae b) |

3.4[37] | * | 1.65[38] – 25[37] | Sometimes the initially reported 6.9 +2.7 −2.9 RJ for the emitting area due to the diffuse dust and gas envelope or debris disk surrounding the planet[39] is confused with the actual radius. HD 100546 is the closest planetary system that contains a Herbig Ae/Be star.[40] |

| 2MASS J0437+2331 | 3.30[41][i] | † | 7.1 +1.1 −1.0[41] |

May be a sub-brown dwarf or a rogue planet | |

|

EV Lacertae | 3.221 ± 0.127[42] (0.331 ± 0.013 R☉) |

# | 335.2 ± 8.38[42] (0.32 ± 0.008 M☉) |

Responsible for the most powerful stellar flare so far observed. Its fast rotation, with its convective interior, produces a powerful magnetic field that is believed to play a role in the star's ability to produce such flares.[43] Reported for reference. |

|

OTS 44 | 3.2 – 3.6[44] | † | 11.5[45] | First discovered rogue planet, and the coolest and faintest object in Chamaeleon I as well as the least massive known member of the cluster at the time of confirmation;[46] very likely a brown dwarf[47] or sub-brown dwarf.[48] It is surrounded by a circumstellar disk of dust and particles of rock and ice. The currently preferred radius estimate is done by SED modelling including substellar object and disk model.[44] |

|

FU Tauri b (FU Tau b) |

3.2 ± 0.3[49] | * | ~ 15.7,[50] 20 ± 4,[51] 19 ± 4[49] |

Likely a part of a binary brown dwarfs or sub-brown dwarfs. |

| Cha J1110-7721 | 3.1[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

2MASS J044144b (2M 0441+23 Bb) |

3.06[52][i] | † | 9.8 ± 1.8[52] | Based on the mass ratio to 2M J044145 A (2M 0441+23 Aa) it is likely not a planet according to the IAU's exoplanet working definition.[7] Part of the lowest mass quadruple 2M 0441+23 system of 0.26 M☉.[52] |

| UGCS J0422+2655 | 2.9[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

| UGCS J0433+2251 | 2.9[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

Kapteyn's Star | 2.83 ± 0.24[53] (0.291 ± 0.025 R☉) |

# | 294.4 ± 14.7[53] (0.2810 ± 0.014 M☉) |

The closest halo star and nearest red subdwarf, at the distance of 12.82 ly (3.93 pc), and second-highest proper motion of any stars of more than 8 arcseconds per year (after the Barnard's Star). Age: 11.5 +0.5 −1.5 Gyr.[54] Reported for reference. |

|

Cha 1107−7626 (Cha J11070768−7626326) |

2.8[28] | † | 6 – 10[55] | Rogue planet; Lowest-mass object with hydrocarbons detected in its disk[55] |

|

AB Aurigae b (AB Aur b) |

< 2.75[56][j] | ! | 20 (~ 4 Myr),[57] 10 – 12 (1 Myr), 9, < 130[56] |

More likely a (proto-)brown dwarf. Assuming a hot-start evolution model and a planetary mass, AB Aurigae b would be younger than 2 Myr to have its observed large luminosity, which is inconsistent with the age of AB Aurigae of 6.0 +2.5 −1.0 Myr, which could be caused by delayed planet formation in the disk.[58] Other system ages include 1 - 5 Myr,[56] 4 ± 1 Myr[59] and 4 Myr.[60] Another source gives a higher mass of 20 MJ in the brown dwarf regime for an age of 4 Myr, arguing since gravitational instability of the disk (preferred formation mechanism in the discovery publication)[56] operates on very short time scales, the object might be as old as AB Aur.[57] A more recent study also support the latter source, given the apparent magnitude was revised upwards.[61] |

|

CT Chamaeleontis b (CT Cha b) |

2.6 +1.2 −0.2[44] |

* | 17 ± 6[62] | Likely a brown dwarf[63] or a planetary mass companion.[64] The NASA Exoplanet Archive considers it as an exoplanet, the most distant to be directly imaged at the distance of 622 ly (190.71 pc).[65] |

|

DH Tauri b (DH Tau b) |

2.6 ± 0.6[32] | ← | 11 ± 3;[35] 12 ± 4[32] |

First planet to have a confirmed circumplanetary disk, detected with polarimetry at the VLT[66] and youngest confirmed planet at an age of 0.7 Myr (700000 years).[32] DH Tauri b is suspected to have an exomoon candidate orbiting it every 320 years, with about the same mass as Jupiter.[67] Other sources give the radii: 2.7 ± 0.8 RJ,[35] 2.49 RJ[44][i] and masses: 14.2 +2.4 −3.5 MJ,[68] 17 ± 6 MJ.[69] |

| HIP 79098 b (HIP 79098 (AB)b) |

2.6 ± 0.6[32] | * | 16 – 25,[70] 28 ± 13[32] |

The mass ratio between HIP 79098 b and the central binary HIP 79098 AB is estimated at 0.3–1%. The value lower than 4% suggests that HIP 79098 b represents the upper end of the planet population, as opposed to having been formed as a star.[70] | |

| UGCS J0439+2642 | 2.5[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

CM Draconis A (Gliese 630.1 Aa) |

2.4437 ± 0.0002[71] (0.25113 ± 0.00016 R☉) |

# | 235.8 ± 0.3[71] (0.22507 ± 0.00024 M☉) |

Second eclipsing binary red dwarf system discovered after YY Geminorum (Castor Cab).[72] One of the lightest stars with precisely measured masses and radii, orbiting around 1.268 days. The members of Gliese 630.1 triple system. Age: 4.1 ± 0.8 Gyr.[73] Reported for reference. |

|

PZ Telescopii b (PZ Tel b, HD 174429 b) |

2.42 +0.28 −0.34[74] |

* | 27 +25 −9[75] |

Likely a brown dwarf. If PZ Tel b is a planet, it would be first large Jupiter-like planet to be directly imaged.[76] |

|

TWA 5 B (TWA 5 A (AB) b) |

2.34 – 3.02[77] | * | 25 +120 −20[78] |

First brown dwarf companion around a pre-main sequence star confirmed by both spectrum and proper motion. Exhibits strong Hα emission.[79] |

|

CM Draconis B (Gliese 630.1 Ab) |

2.3094 ± 0.0001[71] (0.23732 ± 0.00014 R☉) |

# | 220.2 ± 0.3[71] (0.21017 ± 0.00028 M☉) |

Second eclipsing binary red dwarf system discovered after YY Geminorum (Castor C).[72] One of the lightest stars with precisely measured masses and radii, orbiting around 1.268 days. The members of Gliese 630.1 triple system. Age: 4.1 ± 0.8 Gyr.[73] Reported for reference. |

| o005 s41280 | 2.30[80] | † | 8.4[80] | May be a sub-brown dwarf or a rogue planet[80] | |

|

Eta Telescopii B (η Tel B, HR 7329 B) |

2.28 ± 0.03[81] | * | 29 +16 −13[81] |

Part of a triple star system. |

| TWA 29 | 2.222 +0.082 −0.081[82] |

† | 6.6 +5.2 −2.9[82] |

Rogue planet | |

|

ROXs 12 b (2MASS J1626-2526 b, WDS J16265-2527 Ab) |

2.20 ± 0.35[32] | * | 16 ± 4,[83] 19 ± 5[32] |

In 2005, ROXs 12 b was discovered/detected on a wide separation by direct imaging,[84] the same year DH Tauri b, GQ Lupi b, 2M1207b, and AB Pictoris b were confirmed, and was confirmed in 2013.[83] ROXs 12 b and 2MASS J1626–2527 (WDS J16265-2527 B) inclination misalignment with ROXs 12 (WDS J16265-2527 A) was interpreted as either formation similar to fragmenting binary stars or ROXs 12 b formed in an equatorial disk that was torqued by 2MASS J1626–2527. |

| UHW J247.95-24.78 | 2.2[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

Hot Jupiter limit | 2.2[85] | – | ≳ 0.4[86] | Theoretical size limit for hot Jupiters close to a star, that are limited by tidal heating, resulting in 'runaway inflation' |

|

HAT-P-67 Ab | 2.140 ± 0.025[87] | ← | 0.45 ± 0.15[87] | A very puffy Hot Jupiter which is among planets with lowest densities of ~0.061 g/cm3. Largest known planet with a precisely measured radius, as of 2025.[87] |

| PSO J077.1+24 | 2.14[41][i] | † | 5.9 +0.9 −0.8[41] |

Rogue planet | |

| CAHA Tau 1 | 2.12[88][89][i] | † | 10 ± 5[88][89] | Rogue planet | |

|

ROXs 42 Bb | 2.10 ± 0.35[32] | ← | 13 ± 5[32] | The formation is unclear; ROXs 42Bb may formed via core accretion, by disk (gravitational) instability, or more like a binary star. Older estimates include 1.9 – 2.4, 1.3 – 4.7 RJ[90] and 2.43±0.18, 2.55±0.2 RJ.[91] Other sources of masses include 3.2 – 27 MJ,[92] 9 +6 −3 MJ,[93] 10 ± 4 MJ.[94] |

| HATS-15b | 2.019 +0.202 −0.160[95] |

← | 2.17 ± 0.15[95] | ||

|

Proto-Jupiter | 2.0 – 2.59[96][97] | # | ≲ 1;[98][99][100] 1[101] |

Jupiter is most likely formed first and underwent planetary migration, impacting the whole Solar System. During the migration, Jupiter was briefly as close as 1.5 AU to the Sun, likely influencing the formation of Mars, before migrating back to near the ice line by Saturn's gravity.[102][103] Jupiter, as well as Saturn and Neptune, may also be responsible for ejecting fifth giant (or hypothetical Planet Nine if confirmed)[104][105] due to orbital instability between the five giant planets.[106] Due to its radiation emitting more heat than incoming through solar radiation via the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism within its contracting interior,[107][108] Jupiter is currently shrinking by about 1 mm (0.039 in) per year.[109][110] Through this, at the time of its formation, Jupiter was hotter and was about twice its current diameter[111] with smaller mass[100] or the same as the current mass.[101] Reported for reference. |

|

Cha 110913-773444 (Cha 110913) |

2.0 – 2.1[44] | † | 8 +7 −3[112] |

A rogue planet/sub-brown dwarf that is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk, the first one to be confirmed. It is one of youngest free-floating substellar objects with 0.5–10 Myr. The currently preferred radius estimate is done by SED modelling including substellar object and disk model.[44] |

| CFHTWIR-Oph 90 (Oph 90) |

2.00 +0.09 −0.12;[113] 3[114][115] |

† | 10.5[114] | May be rogue planet or brown dwarf | |

| SSTB213 J041757 A (J041757 A) |

2[116] | † | 3.5[116] | In a binary with a smaller 1.7 RJ proto-rogue planet/brown dwarf. It is not clear how proto-brown dwarfs J041757 AB are formed; the observations of the outflow momentum rate of these two proto-BD candidates suggest they formed as a scaled-down version of low-mass stars.[117] | |

|

Kepler-435b (KOI-680 b) |

1.99 ± 0.18[118] | ← | 0.84 ± 0.15[118] | |

|

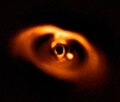

PDS 70 c | 1.98 +0.39 −0.31[119] |

← | 7.5 +4.7 −4.2, 7.8 +5.0 −4.7, ~1 − ~15 (total)[120] |

Second multiplanetary system to be directly imaged (after HR 8799 System). PDS 70 b is first protoplanet to have been ever detected with certainty[121][122] while PDS 70 c is first confirmed directly imaged exoplanet still embedded in the natal gas and dust from which planets form (protoplanetary disk), and the second protoplanet to have a confirmed circumplanetary disk (after DH Tauri b).[123] |

| PDS 70 b | 1.96 +0.20 −0.17,[119] 2.7[58] |

← | 3.2 +3.3 −1.6, 7.9 +4.9 −4.7, < 10 (2 σ), ≲ 15 (total)[120] | ||

| OGLE2-TR-L9b | 1.958 +0.174 −0.111[95] |

← | 4.5 ± 1.5[95] | First discovered planet orbiting a fast-rotating hot star, OGLE2-TR-L9.[124] | |

|

CFHTWIR-Oph 98 A | 1.95 +0.11 −0.10;[113] 2.14[114][125] |

* | 15.4 ± 0.8;[126] 10.5[114] |

Either a M-type brown dwarf or sub-brown dwarf with a sub-brown dwarf/planet companion CFHTWIR-Oph 98 b. Other sources of masses includes: 9.6 – 18.4 MJ.[126] |

| WASP-178b (KELT-26 b, HD 134004 b) |

1.940 +0.060 −0.058[127] |

← | 1.41 +0.43 −0.51[127] |

An ultra-hot Jupiter. Initially, the planet's atmosphere was discovered having silicon monoxide, making this exoplanet the first one to have the compound on its atmosphere,[128] now the atmosphere is more likely dominated by ionized magnesium and iron.[129] | |

|

WASP-12Ab | 1.937 ± 0.056[130] | ← | 1.476 +0.076 −0.069[131] |

This planet is so close to WASP-12 A that its tidal forces are distorting it into an egg-like shape.[132] First planet observed being consumed by its host star;[133] it will be destroyed in 3.16 ± 0.10 Ma due to tidal interactions.[134][135] WASP-12b is suspected to have one exomoon due to a curve of change of shine of the planet observed regular variation of light.[136] |

| BD-14 3065b (TOI-4987 b) |

1.926 ± 0.094[137] | * | 12.37 ± 0.92[137] | Might be a brown dwarf fusing deuterium at its core, which could explain its anomalous high radius. Also the fourth hottest known exoplanet, measuring 3,520 K (3,250 °C; 5,880 °F).[137] | |

|

Kepler-13 Ab | 1.91 ± 0.25 – 2.57 ± 0.26[138] | ← | 9.28(16)[139] | Discovered by Kepler in first four months of Kepler data.[140] A more recent analysis argues that a third-light correction factor of 1.818 is needed, to correct for the light blending of Kepler-13 B, resulting in higher radii results.[138] |

|

KELT-9b (HD 195689 b) |

1.891 +0.061 −0.055[141] |

← | 2.17 ± 0.56[142] | Hottest confirmed exoplanet, with a temperature of 4050±180 K (3777 ± 180 °C; 6830 ± 324 °F).[143] First exoplanet with detection of the rare-earth element terbium in atmosphere.[144] |

| TOI-1518 b | 1.875 ± 0.053[145] | ← | 1.83 ± 0.47[146] | ||

|

HAT-P-70b | 1.87 +0.15 −0.10[147] |

← | < 6.78 (3 σ)[147] | Has a retrograde orbit.[147] |

| 2MASS J1935-2846 | 1.869 ± 0.053[148] | † | 7.4 +6.3 −3.4[148] |

May be a sub-brown dwarf or rogue planet. | |

| HATS-23b | 1.86 +0.30 −0.40[149] |

→ | 1.470 ± 0.072[149] | Grazing planet. | |

|

CFHTWIR-Oph 98 b (Oph 98 b, CFHTWIR-Oph 98 B) |

1.86 ± 0.05[126][125] | † | 7.8 +0.7 −0.8[126] |

Its formation as an exoplanet is challenging or impossible.[126] If its formation scenario is known, it may explain the formation of Planet Nine. Planetary migration may explain its formation, or it may be a sub-brown dwarf. Other sources of mass includes 4.1 – 11.6 MJ.[126] |

| KELT-8b (HD 343246 b) |

1.86 +0.18 −0.16[150] |

← | 0.867 +0.065 −0.061[150] |

||

|

WASP-76b | 1.842 ± 0.024[151] | ← | 0.921 ± 0.032[152] | A glory effect in the atmosphere of WASP-76b might be responsible for the observed increase in brightness of its eastern terminator zone which if confirmed, it would become the first glory-like phenomenon to be discovered on an exoplanet.[153][154] WASP-76b is suspected to have an exomoon analogue to Jupiter's Io due to the detection of sodium via absorption spectroscopy.[155] |

|

KPNO-Tau 12 (2MASS J0419012+280248) |

1.84,[26] 2.22 +0.11 −0.17[113] |

† | 11.5[114] | A low-mass brown dwarf or free-floating planetary-mass object surrounded by a protoplanetary disk. A member of Taurus-Auriga star-forming region.[26] Other sources of masses include: 14.6 MJ,[26] 13.6 MJ,[156] 6-7 MJ,[157] 16.5 MJ,[158] 17.8 +6.7 −4.6 MJ,[159] 12.7 +1.6 −1.8 MJ[113] |

|

TrES-4 (GSC 06200-00648 Ab) |

1.838 +0.240 −0.238[95] |

← | 0.78 ± 0.19[160] | Largest confirmed exoplanet ever found at the time of discovery.[161] This planet has a density of 0.17 g/cm3, comparable to that of balsa wood, less than Saturn's 0.7 g/cm3.[95] |

| HIP 78530 b (HIP 78530 B) |

1.83 +0.16 −0.14[162] |

* | 28 ± 10[162] | Most likely a brown dwarf. Because HIP 78530 b's characteristics blend the line between whether or not it is a brown dwarf or a planet, astronomers have tried to determine what HIP 78530 b is by predicting whether it was created in a planet-like or star-like manner.[163] | |

| HAT-P-33b | 1.827 ± 0.29,[164][k] 1.85 ± 0.49,[160] 1.686 ± 0.045[164][l] |

← | 0.72 +0.13 −0.12[165] |

Due to high level of jitter, it is difficult to constrain both planets' eccentricities with accuracy. Most of their defined characteristics are based on the assumption that HAT-P-32b and HAT-P-33b have their elliptical orbits, although their discoverers have also derived the planets' characteristics on the assumption that they have their circular orbits. The elliptical model has been chosen because it is considered to be the more likely scenario.[164] | |

| HAT-P-32b (HAT-P-32 Ab) |

1.822 +0.350 −0.236,[95] 2.04 ± 0.10,[164][k] 1.789 ± 0.025[164][l] |

← | 0.941 ± 0.166, 0.860 ± 0.164[164] | ||

|

KELT-20b (MASCARA-2b) |

1.821±0.045[152] | ← | 3.355+0.062 −0.063[152] |

An ultra-hot Jupiter. |

|

YSES 1 b (TYC 8998-760-1 b) |

1.82 ± 0.08,[166] 3.0 +0.2 −0.7[167] |

* | 21.8 ± 3[168] | Likely a brown dwarf. First substellar object to have an isotope variant of stable element (13C) detected in its atmosphere.[169][166] First directly imaged planetary system having multiple bodies orbiting a Sun-like star.[170][171] |

|

Barnard's Star (Proxima Ophiuchi) |

1.82 ± 0.01[172] (0.187 ± 0.001 R☉) |

# | 168.7 +3.8 −3.7[172] (0.1610 +0.0036 −0.0035 M☉) |

Second nearest planetary system to the Sun at the distance of 5.97 ly (1.83 pc) and closest star in the northern celestial hemisphere. Also the highest proper motion of any stars of 10.3 arcseconds per year relative to the Sun. Has 4 confirmed planet, Barnard b (Barnard's Star b),[173] c, d and e,[174] making this system second closest planetary system to host multiple planets after Proxima System.[175] Reported for reference. |

|

CoRoT-1b | 1.805 +0.132 −0.131[95] |

← | 1.03 ± 0.12[95] | First exoplanet for which optical (as opposed to infrared) observations of phases were reported.[176] |

| WTS-2b | 1.804 +0.144 −0.158[95] |

← | 1.12 ± 0.16[95] | ||

| UGCS J0417+2832 | 1.8[28] | † | 5 – 10[28] | Rogue planet | |

|

Saffar (υ And Ab) |

~1.8[177] | ← | 1.70 +0.33 −0.24[178] |

Radius estimated using the phase curve of reflected light. The planet orbits very close to Titawin (υ And A) at the distance of 0.0595 AU, completing an orbit in 4.617 days.[179] First multiple-planet system to be discovered around a main-sequence star, and first multiple-planet system known in a multiple-star system. |

| HAT-P-40b | 1.799 +0.237 −0.260[95] |

← | 0.48 ± 0.13[95] | A very puffy hot Jupiter | |

| WASP-122b (KELT-14b) |

1.795 +0.107 −0.079[95] |

← | 1.284 ± 0.032[180] | ||

| KELT-12b | 1.79 +0.18 −0.17[181] |

← | 0.95 ± 0.14[181] | ||

|

Tylos (WASP-121b) |

1.773 +0.041 −0.033[182] |

← | 1.157 ± 0.07[182] | First exoplanet found to contain water on its stratosphere. Tylos is suspected to have an exomoon analogous to Jupiter's Io due to the detection of sodium absorption spectroscopy around it.[183] |

| TOI-640 Ab | 1.771 +0.060 −0.056[184] |

← | 0.88 ± 0.16[184] | This planet orbits its host star nearly over poles, misalignment between the orbital plane and equatorial plane of the star been equal to 104 ± 2°[185] | |

| WASP-187b | 1.766 ± 0.036[186] | ← | 0.801 +0.084 −0.083[186] |

||

| WASP-94 Ab | 1.761 +0.194 −0.191[95] |

← | 0.5±0.13[95] | ||

| TOI-2669b | 1.76 ± 0.16[187] | ← | 0.61 ± 0.19[187] | ||

| WISE J0528+0901 | 1.752 +0.292 −0.195[188] |

† | 13 +3 −6[188] |

Brown dwarf or rogue planet | |

| HATS-26b | 1.75 ± 0.21[189] | ← | 0.650 ± 0.076[189] | ||

| Kepler-12b | 1.7454 +0.076 −0.072[190] |

← | 0.431 ± 0.041[191] | Least-irradiated of four Hot Jupiters at the time of discovery | |

| HAT-P-65b | 1.744 +0.165 −0.215[95] |

← | 0.527 ± 0.083[192] | This planet has been suffering orbital decay due to its close proximity to HAT-P-65; 0.04 AU.[193] | |

| 2MASS J2352-1100 | 1.742 +0.035 −0.036[148] |

† | 12.4 +9.4 −5.5[148] |

Brown dwarf or rogue planet | |

| KELT-15b | 1.74 ± 0.20[160] | ← | 1.31 ± 0.43[160] | ||

| HAT-P-57b | 1.74 ± 0.36[160] | ← | 1.41 ± 1.52[160] | ||

| WASP-93b | 1.737 +0.121 −0.170[95] |

← | 1.47 ± 0.29[95] | ||

| WASP-82b | 1.726 +0.163 −0.195[95] |

← | 1.17 ± 0.20[95] | ||

|

Ditsö̀ (WASP-17b) |

1.720 +0.004 −0.005, 1.83 ± 0.01[194] |

← | 0.512 ± 0.037[195] | First planet discovered to have a retrograde orbit[196] and first to have quartz (crystalline silica, SiO2) in its clouds.[197] Has an exteremely low density of 0.08 g/cm3,[196] the lowest of any exoplanet when it was discovered, and was possibly the largest exoplanet at the time of discovery, with a radius of 1.92 RJ.[198] |

| KELT-19 Ab | 1.717 +0.094 −0.093[152] |

← | 3.98+0.32 −0.33[152] |

First exoplanet found to have its orbit flipped (obliquity of 155 +17 −21°) due to constraints on stellar rotational velocity, sky-projected obliquity and limb-darkening coefficients (see Kozai–Lidov mechanism).[199] | |

| HAT-P-39b | 1.712+0.140 −0.115[95] |

← | 0.60±0.10[95] | ||

| KELT-4Ab | 1.706 +0.085 −0.076[200] |

← | 0.878 +0.070 −0.067[200] |

Fourth planet found in triple star system.[201] KELT-4A is the brightest host (V~10) of a Hot Jupiter in a hierarchical triple stellar system found.[202] | |

| Pollera (WASP-79b) |

1.704 +0.195 −0.180,[95] 2.09 ± 0.14[203] |

← | 0.850 +0.180 −0.180[95] |

This planet is orbiting the host star at nearly-polar orbit with respect to star's equatorial plane, inclination being equal to −95.2+0.9 −1.0°.[204] | |

| HAT-P-64b | 1.703 ± 0.070[205] | ← | 0.58 +0.18 −0.13[205] |

||

| WASP-78b | 1.70 ± 0.04,[203] 1.93 ± 0.45[160] |

← | 0.89 ± 0.08[203] | This planet has likely undergone in the past a migration from the initial highly eccentric orbit.[206] | |

| Qatar-7b | 1.70 ± 0.03[207] | ← | 1.88 ± 0.25[207] | ||

| SSTB213 J041757 B (J041757 B) |

1.70[116] | † | 1.50[116] | In a binary with a larger 2 RJ proto-rogue planet/brown dwarf. It is not clear how proto-brown dwarfs J041757 AB are formed; the observations of the outflow momentum rate of these two proto-BD candidates suggest they formed as a scaled-down version of low-mass stars.[117] | |

| CoRoT-17b | 1.694 +0.139 −0.193[95] |

← | 2.430±0.300[95] | Hot Jupiter | |

| TOI-615b | 1.69+0.06 −0.05[208] |

← | 0.43+0.09 −0.08[208] |

||

| CoRoT-35b | 1.68 ± 0.11[209] | ← | 1.10 ± 0.37[209] | ||

|

1RXS 1609 b (1RXS J160929.1−210524 b, 1RXS J1609 b) |

~ 1.664,[210] 1.7[211] |

! | 14 +2 −3,[212] 12.6 – 15.7,[211] 12 ± 2[51] |

Thought to be the lightest known exoplanet at the time of announcement orbiting its host at a large separation of 330 AU and third announced directly imaged exoplanet orbiting a sun-like star (after GQ Lup b and AB Pic b). 1RXS 1609 b's location far from 1RXS 1609 presents serious challenges to current models of planetary formation: the timescale to form a planet by core accretion at this distance from the star would be longer than the age of the system itself. One possibility is that the planet may have formed closer to the star and migrated outwards as a result of interactions with the disk or with other planets in the system. An alternative is that the planet formed in situ via the disk instability mechanism, where the disk fragments because of gravitational instability, though this would require an unusually massive protoplanetary disk.[210] With the upward revision in the age of the Upper Scorpius group from 5 million to 11 million years, the estimated mass of 1RXS J1609b is approximately 14 MJ, i.e. above the deuterium-burning limit.[212] An older age for the J1609 system implies that the luminosity of J1609b is consistent with a much more massive object, making more likely that J1609b may be simply a brown dwarf which formed in a manner similar to that of other low-mass and substellar companions.[211] |

| TOI-1855 b | 1.65 +0.52 −0.37[213] |

← | 1.133 ± 0.096[213] | ||

| TOI-3807 b | >1.65 (95% lower limit)[214] | → | 1.04 +0.15 −0.14[214] |

Grazing planet, a large radius of 2.00 RJ derived from transit data is unreliable due to its grazing nature. | |

|

HAT-P-7b (Kepler-2b) |

1.64 ± 0.11[215] | ← | 1.806 ± 0.036[195] | Second planet discovered to have a retrograde orbit (after Ditsö̀)[216][217] and first exoplanet to be detected by ellipsoidal light variations[218] |

| NGTS-33 b | 1.64 ± 0.07[219] | ← | 3.6 ± 0.3[219] | ||

| HAT-P-64b | 1.631 ± 0.070[205] | ← | 0.574 ± 0.038[205] | ||

| WASP-82b | 1.62 ± 0.13[160] | ← | 1.17 ± 0.20[160] | ||

| KELT-8b | 1.62 ± 0.10[160] | ← | 0.66 ± 0.12[160] | ||

| WASP-189 b | 1.619 ± 0.021[220] | ← | 1.99 +0.16 −0.14[220] |

Fifth hottest known exoplanet, at an temperature of 3,435 K (3,162 °C; 5,723 °F). | |

| HAT-P-65b | 1.611 ± 0.024[221] | ← | 0.554 +0.092 −0.091[221] |

This planet has been suffering orbital decay due to its proximity.[193] | |

| K2-52b | 1.61 ± 0.20[222] | ← | 0.40 ± 0.35[222] | ||

| NGTS-31 b | 1.61 ± 0.16[223] | ← | 1.12 ± 0.12[223] | ||

| HATS-11b (EPIC 216414930b) |

1.609 ± 0.064[224] | ← | 0.85[224] | ||

| KELT-7b | 1.60 ± 0.06[160] | ← | 1.39 ± 0.22[160] | ||

| A few notable examples with radii below 1.6 RJ (17.93 R🜨). | |||||

|

Delorme 1b (2MASS J0103-5515 (AB) b, 2MASS0103(AB)b) |

~ 1.59[225] | ? | 13 ± 1[226] | The formation is unclear. The high accretion is in better agreement with a formation via disk fragmentation, hinting that it might have formed from a circumstellar disk.[227] Giant planets and brown dwarfs are thought to form via disk fragmentation in rare cases in the outer regions of a disk (r > 50 AU).[228] Teasdale & Stamatellos modelled three formation scenarios in which the planet could have formed. In the first two scenarios the planet forms in a massive disk via gravitational instability. The first two scenarios produce planets that have accretion and separation comparable to the observed ones, but the resulting planets are more massive than Delorme 1 b. In a third scenario the planet forms via core accretion in a less massive disk much closer to the binary. In this third scenario the mass and accretion are similar to the observed ones, but the separation is smaller.[229] |

|

2M1510 A (2MASS J1510–28 A, 2M1510 Aa)[m] |

1.575[230] (0.16185 R☉) |

# | 34.676 ± 0.076[231] (0.033101(73) M☉) |

Second eclipsing binary brown dwarf system discovered and first kind of system to be directly imaged, orbiting around 20.9 days.[232][230] The members of 2M1510 triple (likely)[231] or quadruple system.[232] Age: 45 ± 5 Myr Have a strong candidate planet, 2M1510 b (2M1510Aab b), that orbits polar around 2M1510AB (or 2M1510Aab),[m] making this planet the first planet discovered orbiting polar around a binary system.[231][233][234] Reported for reference. |

| 2M1510 B (2MASS J1510–28 B, 2M1510 Ab)[m] |

# | 34.792 ± 0.072[231] (0.033212(69) M☉) | |||

|

Kepler-7b | 1.574 +0.075 −0.071[190] |

← | 0.433 +0.040 −0.041[235] |

One of the first five exoplanets to be confirmed by the Kepler spacecraft, within 34 days of Kepler's science operations,[236] and the first exoplanet to have a crude map of cloud coverage.[237][238][239] |

|

WASP-103b | 1.528 +0.073 −0.047[195] |

← | 1.455 +0.090 −0.091[195] |

First exoplanet to have a deformation detected.[240] (see Jacobi ellipsoid) |

|

HIP 99770 b (29 Cygni b) |

1.5 ± 0.3[241] | * | 17 +6 −5[241] |

First joint direct imaging and astrometric discovery of a planetary mass companion and the first planetary mass companion discovered using precision astrometry from the Gaia mission.[242] Likely a brown dwarf. |

|

2MASS J1115+1937 | 1.5 ± 0.1[243] | † | 6 +8 −4[243] |

Nearest rogue planet surrounded by planetary disk at the distance of 147 ± 7 ly (45.1 ± 2.1 pc).[243] |

|

Proxima (Proxima Centauri, Alpha Centauri C) |

1.50 ± 0.04[244] (0.1542 ± 0.0045 R☉) |

# | 127.9 ± 2.3[244] (0.1221 ± 0.0022 M☉) |

Nearest (flare) star and planetary system to the Sun, at a distance of 4.24 ly (1.30 pc), orbiting around Alpha Centauri AB System, the nearest star system to the Sun. Age: 4.85 Gyr.[245] Has two confirmed planets, Proxima b (Proxima Centauri b)[246] and Proxima d,[175] and a disputed planet, Proxima c,[247] making Proxima the nearest planetary system to host more than one planet, supplanting Barnard System,[n] and nearest one in multi-star system. Reported for reference. |

|

Najsakopajk (HIP 65426 b) |

1.44 ± 0.03[248] | ← | 7.1 ± 1.2, 9.9 +1.1 −1.8, 10.9 +1.4 −2.0[248] |

First exoplanet to be imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope.[249] The JWST direct imaging observations tightly constrained its bolometric luminosity, which provides a robust mass constraint of 7.1 ± 1.2 MJ. The atmospheric fitting of both temperature and radius are in disagreement with evolutionary models. Moreover, this planet is around 14 million years old which is however not associated with a debris disk, despite its young age,[250][251] causing it to not fit current models for planetary formation.[252] |

|

Banksia (WASP-19b) |

1.386 ± 0.032[253] | ← | 1.168 ± 0.023[253] | First exoplanet to have its secondary eclipse and orbital phases observed from the ground-based observations[254] and first to have titanium oxide (TiO) detected in an exoplanet atmosphere.[255][256] |

|

HD 209458 b ("Osiris") |

1.359 +0.016 −0.019[195] |

← | 0.682 +0.014 −0.015[195] |

Represents multiple milestones in exoplanetary discovery, such as the first exoplanet known observed to transit its host star, the first exoplanet with a precisely measured radius, one of first two exoplanets (other being HD 189733 Ab) to be observed spectroscopically[257][258] and the first to have an atmosphere detected, containing evaporating hydrogen, and oxygen and carbon. First extrasolar gas giant to have its superstorm measured.[259] Also first (indirect) detection of a magnetic field on an exoplanet.[260] This planet is on process of stripping its atmosphere due to extreme "hydrodynamic drag" created by its evaporating hydrogen atmosphere.[261] Nicknamed "Osiris". |

|

TOI-2109 b | 1.347 ± 0.047[262] | ← | 5.02 ± 0.75[262] | Has the shortest orbital period among the hot Jupiters in 0.6725 days (16.14 hours) and highest rotational rate as well as the largest size and mass among the 12 known Jovian ultra-short period planets.[263] TOI-2109 b has the third hottest dayside temperature of 3,631 K (3,358 °C; 6,076 °F), after 55 Cancri e (Janssen) and KELT-9b.[262] |

|

Teide 1 | 1.311 +0.120 −0.075[148] (0.1347 +0.0123 −0.0077 R☉) |

# | 52 +15 −10[148] (0.0496 +0.0143 −0.0095 M☉) |

The first brown dwarf to be confirmed.[264][265] It is located in the Pleiades and has an age of 70 – 140 Myr.[266] Reported for reference. |

|

AF Leporis b (AF Lep b) |

1.30 ± 0.15[267] | ← | 3.74 +0.53 −0.50[268] |

First companion below the deuterium burning limit to be detected with direct imaging after astrometric prediction. |

|

OGLE-TR-56b | 1.30 ± 0.05 | ← | 1.29 ± 0.12 | First discovered exoplanet using the transit method.[269] |

|

BD+60 1417b (W1243) |

1.29 ± 0.06[270] | * | 13.47 ± 5.67[270] | First directly imaged exoplanet discovered by a citizen scientist. This planet orbits around BD+60 1417 at the distance of 1662 AU, making this host star the only main sequence star with about 1 M☉ that is orbited by a planetary-mass object at a separation larger than 1000 AU.[271] Its status of exoplanet is unclear; according to the NASA Exoplanet Archive BD+60 1417b is an exoplanet[272] and it falls within their definition: An object with a minimum mass lower than 30 MJ and a not free-floating object with sufficient follow-up.[5] However, the official working definition by the International Astronomical Union allows only exoplanets with a maximum mass of 13 MJ and according to current knowledge BD+60 1417b could be more massive than this limit and might be a brown dwarf.[6] |

|

TOI-157b | 1.29 ± 0.02[273] | ← | 1.18 ± 0.13[273] | Oldest confirmed planet at an age of 12.9 +1.4 −0.69 Gyr[273] |

|

Bocaprins (WASP-39b) |

1.27 ± 0.04[274] | ← | 0.28 ± 0.03[274] | First exoplanet found to contain carbon dioxide[275][276] and sulfur dioxide[277] in its atmosphere. |

|

TrES-2 (Kepler-1 Ab) |

1.265 +0.054 −0.051[190] |

← | 1.199 ± 0.052[278] | Darkest known exoplanet due to an extremely low geometric albedo of 0.0136, absorbing 99% of light. |

|

Dimidium (51 Pegasi b) |

1.2 ± 0.1[279] | ← | 0.46 +0.06 −0.01[280] |

First exoplanet to be discovered orbiting a main-sequence star.[281] Prototype of the hot Jupiters. |

|

Nu Octantis Ab (ν Octantis Ab) |

1.19[282] | ← | 2.19 ± 0.11[283] | Has the tightest orbit around a star in a binary star system. The formation and long-term stability of a planet on such a tight orbit and retrograde orbit relative to the binary's motion are challenging, but with the secondary being a white dwarf that lost most part of its mass during the evolution to a red giant and then to a white dwarf, both can be explained with either the instability of a former circumbinary planetary system that lead one of the planets to migrate inwards or by planetary formation by a second-generation protoplanetary disk that emerged from death of the white dwarf's progenitor.[283] Radius is an estimate.[282] |

|

HR 8799 b | 1.2 ± 0.1[284] | ← | 6.0 ± 0.3[285] | First directly imaged planetary system having multiple exoplanets and first directly imaged exoplanets to have their orbital motion confirmed. HR 8799 e is also the first exoplanet to be directly observed using optical interferometry. All four planets will cool and shrink to about the same size as Jupiter, see Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism. The outer planet orbits inside a dusty disk like the Solar Kuiper belt. |

| HR 8799 c | ← | 8.5 ± 0.4[285] | |||

| HR 8799 d | ← | 9.2 ± 0.1[285] | |||

| HR 8799 e | 1.17 +0.13 −0.11[286] |

← | 9.6 +1.9 −1.8[287] | ||

|

Ahra (WD 0806-661 b) |

1.17 ± 0.07; 1.12 ± 0.07[288] |

‽ | 6.8 – 9.0,[289] 6.3 – 9.4 (2 ± 0.5 Gyr);[288] 0.45 – 1.75 (60 – 180 Myr)[288] |

First exoplanet discovered around a single (as opposed to binary) white dwarf, and the coldest directly imaged exoplanet when discovered.[290] Possibly formed closer to Maru (WD 0806−661) when it was a main sequence star, this object migrated further away as it reached the end of its life (see stellar evolution), with a current separation of about 2500 AU. Alternatively, based on its large distance from the white dwarf, it likely formed like a star rather than in a protoplanetary disk, and it is generally described as a (sub-)brown dwarf in the scientific literature.[291] The planet was observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, which probed the atmosphere of the object, carried out with the Mid-Infrared Instrument medium resolution spectroscopy. The spectrum is dominated by absorption of water vapor, ammonia and methane. The molecules carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are not detected, but the researchers determine the upper limits of their abundance. The atmosphere of Ahra is mostly consistent with theoretical models. Some results are however at odds with theoretical models, such as the non-detection of water clouds and the mixing ratio of ammonia. The retrieved mass of 0.45 – 1.75 MJ is smaller than expected (6.3 – 9.4 MJ), possibly hinting at a younger age or an incorrect retrieved mass.[288] Might be considered an exoplanet or a sub-brown dwarf, the dimmest sub-brown dwarf. The IAU considers objects below the ~13 MJ limiting mass for deuterium fusion that orbit stars (or stellar remnants) to be planets, regardless on how they formed.[292] |

|

TRAPPIST-1 | 1.16 ± 0.01[293] (0.1192 ± 0.0013 R☉) |

# | 94.1 ± 2.4[293] (0.0898 ± 0.0023 M☉) |

Coldest and smallest known star hosting exoplanets.[294] All seven exoplanets are rocky planets, orbiting closer to the star than Mercury. Their orbits' inclinations of 0.1 degrees[295] makes TRAPPIST-1 system the flattest planetary system.[296] Age: 7.6 ± 2.2 Gyr.[297] Reported for reference. |

|

HD 189733 Ab | 1.138 ± 0.027[195] | ← | 1.123 ± 0.045[195] | First exoplanet to have its thermal map constructed,[298] its overall color (deep blue) determined,[299][300] its transit viewed in the X-ray spectrum, one of first two exoplanets (other being "Osiris") to be observed spectroscopically[257][258] and first to have carbon dioxide confirmed as being present in its atmosphere. Such the rich cobalt blue[301][302] colour of HD 189733 Ab may be the result of Rayleigh scattering. The wind can blow up to 8,700 km/h (5,400 mph) from the day side to the night side.[303] |

|

VHS 1256 b (VHS 1256-1257 b) |

1.13 – 1.21[304] | * | 19 ± 5;[305] 12.0 ± 0.1 – 16 ± 1[305] |

VHS 1256 b has its rotational axis tilted at 90°±25° which is same as that of Uranus. However, unlike Uranus, its origin rules out planet-like scenarios such as collisions and spin-orbit resonances. This suggests that VHS 1256 b more likely formed via core/filament fragmentation.[306] This is also further proven by the presence of methane and water which if reacted each other, release hydrogen and carbon monoxide, both being common in the atmosphere of brown dwarfs, and silicate clouds within the atmosphere of VHS 1256 b with silicate clouds being the first direct detected in a planetary-mass object's atmosphere.[307] |

|

SWEEPS-11 | 1.13 ± 0.21[308] | ← | 9.7 ± 5.6[308] | One of two most distant planets (other being SWEEPS-04) discovered at a distance of 27 710 ly (8500 pc).[309] |

|

2M1207 b (TWA 27b) |

1.13[310] | † | 5.5 ± 0.5[310] | First planetary body in an orbit discovered via direct imaging, and the first around a brown dwarf.[311][312] It could be considered a sub-brown dwarf due to its large mass in relation to its host: 2M1207 b is around six times more massive than Jupiter, but orbits a 26 MJ brown dwarf, a ratio much larger than the 1:1000 of Jupiter and Sun for example. The IAU defined that exoplanets must have a mass ratio to the central object less than 0.04,[313][7] which would make 2M1207b a sub-brown dwarf. Nevertheless, 2M1207b has been considered an exoplanet by press media and websites,[314][315][316] exoplanet databases[317][318] and alternative definitions.[319] It will shrink to a size slightly smaller than Jupiter as it cools over the next few billion years, see Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism. |

|

WASP-47 b | 1.128 ± 0.013[320] | ← | 1.144 ± 0.023[321] | Super Earth WASP-47 e orbits even closer than hot Jupiter WASP-47 b and both hot Neptune WASP-47 d and outer gas planet WASP-47 c orbit further than the hot Jupiter, making WASP-47 system the only planetary system to have both planets near the hot Jupiter and another planet much further out.[322] |

|

2MASS J0523−1403 | 1.126 ± 0.063[323] (0.116 ± 0.006 R☉) |

# | 73.3[324] (0.07 M☉) |

Coolest main sequence star with effective temperature 1939 K (1666 °C; 3031 °F)[325] and one of the smallest stars, in both radius and mass.[326] Reported for reference. |

|

CoRoT-3 Ab | 1.08 ± 0.05[327] | * | 21.66 ± 1.00[328] | Might be considered either a planet or a brown dwarf, depending on the definition chosen for these terms. If the brown dwarf/planet limit is defined by mass regime using the deuterium burning limit as the delimiter (i.e. 13 MJ), CoRoT-3 Ab is a brown dwarf.[329] If formation is the criterion, CoRoT-3 Ab may be a planet given that some models of planet formation predict that planets with masses up to 25–30 Jupiter masses can form via core accretion.[330] However, it is unclear which method of formation created CoRoT-3 Ab. The issue is clouded further by the orbital properties of CoRoT-3 Ab: brown dwarfs located close to their stars are rare, while the majority of the known massive close-in planets (e.g, XO-3b, HAT-P-2b and WASP-14b) are in highly eccentric orbits, in contrast to the circular orbit of CoRoT-3 Ab.[328] |

|

Gliese 504 b (59 Virginis b) |

1.08 +0.04 −0.03[331] |

! | 1.0 +1.8 −0.3 – 17[331] |

First directly imaged planet containing methane absorption in the infrared H band[332] and ammonia in the atmosphere.[331] The mass of Gliese 504 b is hard to measure, as it depends on the host star's age, which is poorly known. The discoverers adopted an age value 0.16+0.35 −0.06 Gyr and estimated mass as 4.0 +4.5 −1.0 MJ[333] while other astronomers obtained an age value of 4.5 +2.0 −1.5 Gyr, which corresponds to 20 – 30 MJ. In this case, the object is a brown dwarf rather than a planet.[334] Intermediate ages were proposed in 2025, ranging from 400 million to one billion years, which would imply a mass between one and 17 MJ, still not sufficient to confirm the nature of GJ 504 b. Measuring the abundance of ammonia in the planet's atmosphere could constrain its mass, current measurements suggest a mass likely within the planetary-mass regime, while the mid-infrared brightness seems to place the object at a higher age and mass.[331] Ages between 360 million and 2.5 billion years were proposed in another 2025 study.[335] |

|

Epsilon Indi Ab (ε Ind b) |

1.08[336][i] | ← | 6.31 +0.60 −0.56[336] |

Nearest and one of the two coldest extrasolar planets directly imaged.[337] Second closest Jovian exoplanet to the Solar System, after AEgir (ε Eridani b). |

|

Kepler-1647 b | 1.05932 ± 0.01228[338] | ← | 1.52 ± 0.65[338] | Longest transit orbital period of any confirmed transiting exoplanet discovered at the duration of 1107 days[339] and largest circumbinary planet discovered.[340] This planet is located within the habitable zone of binary star system Kepler-1647 and thus could theoretically have a habitable Earth-like exomoon.[341] |

|

14 Herculis c (14 Her c) |

1.03 ± 0.01[342] | ← | 7.9 +1.6 −1.2[342] |

One of the two coldest extrasolar planets directly imaged and possibly the oldest at age 4.6 +3.8 −1.3 Gyr, comparable to the age of the Solar System.[342] |

|

Kepler-90h | 1.01 ± 0.09[343] | ← | 0.639 ± 0.016[344] | Located in the Kepler-90 system with eight known exoplanets, whose architecture is similar to that of the Solar System, with rocky planets being closer to the star and gas giants being more distant. This planet is located at 1.01 AU from its star, which is within the habitable zone of Kepler-90 and thus could theoretically have a habitable Earth-like exomoon. |

|

Jupiter | 1 (11.209 R🜨)[o][11] (71 492 km) |

# | 1 (317.827 M🜨)[345] (1.898 125 × 1027 kg) |

Oldest, largest and most massive planet in the Solar System;[346] this planet hosts 95 known moons including the Galilean moons. Reported for reference. |

|

Luhman 16 B (WISE 1049−5319 B) |

0.99 ± 0.05[347] | * | 29.4 ± 0.2[348] | Closest brown dwarfs found since the measurement of the proper motion of Barnard's Star,[349][350] and the third-closest-known system and closest true binary star system to the Sun at a distance of 6.51 ly (2.00 pc) (after the Alpha Centauri system and Barnard's Star). While Luhman 16 B is commonly seen as brown dwarf, NASA Exoplanet Archive list Luhman 16 B as exoplanet that is orbiting around Luhman 16 A, being the most massive among the list.[8] |

|

WASP-107b | 0.96 ± 0.03[351] | ← | 0.096 ± 0.005[351] | One of lowest-density exoplanets found.[351] First exoplanet with helium detection in atmosphere.[352] |

|

IRAS 04125+2902 b (TIDYE-1 b) |

0.958 +0.077 −0.075[353] |

← | < 0.3[353] (< 90 M🜨) |

Youngest transiting exoplanet discovered, with an age of just three Myr.[353] This planet will shed its outer layers during its evolution, becoming either a sub-Neptune, super-Earth or a sub-Saturn, with the radius shrinking to 1.5 – 4 R🜨 if the planet becomes a super-Neptune or 4 – 7 R🜨 if it becomes a sub-Saturn.[354] |

|

WD 1856+534 b (TOI-1690 b, WDS J18576+5331 Ab) |

0.946 ± 0.017[355] | ← | 0.84[356] – 5.2 +0.7 −0.8[355] |

Coldest exoplanet directly detected at a temperature of 186 +6 −7 K[357] and first and only transiting true planet to be observed orbiting a white dwarf.[355] This gas giant orbits its host star closely at a distance of 0.02 AU. This indicates that the planet may have migrated inward after its host star evolved from a red giant to a white dwarf, otherwise it would have been engulfed by its star.[355] This migration may be related to the fact that WD 1856+534 belongs to a hierarchical triple-star system: the white dwarf and its planet are gravitationally bound to a distant companion, G 229–20AB, which itself is a binary system of two red dwarf stars.[355] Gravitational interactions with the companion stars may have triggered the planet's migration through the Lidov–Kozai mechanism[358][359][360] in a manner similar to some hot Jupiters. Another alternative hypothesis is that the planet instead has survived a common envelope phase.[361] In the latter scenario, other planets engulfed before may have contributed to the expulsion of the stellar envelope.[362] JWST observations seem to disfavour the formation via common envelope and instead favour high eccentricity migration.[363] |

|

WISE 0855−0714 | 0.89[364] | † | ~3 – 10[364] | Coldest (sub-)brown dwarf discovered, having a temperature of about 285 K (12 °C; 53 °F). It is also the fourth-closest star and closest sub-brown dwarf (or possibly rogue planet) to the Sun at the distance of 7.43 ± 0.04 ly (2.278 ± 0.012 pc).[364] The mass and age of WISE 0855−0714 are neither known with certainty.[365] Also deuterium was detected, confirming it to be less massive than the deuterium burning limit.[366] |

|

Saturn | 0.84298 (9.449 R🜨)[o][367] |

# | 0.299 42 (95.16 M🜨)[367] |

Second oldest and least dense planet in the Solar System;[368] this planet hosts the most number of moons of 274 known moons including Rhea and Titan. While the gas giants do have ring systems, Saturn is the most notable for its visible ring system. Reported for reference. |

| For smaller exoplanets, see the list of smallest exoplanets or other lists of exoplanets. For exoplanets with milestones, see the list of exoplanet extremes and list of exoplanet firsts. | |||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ The measured radius from 2003 to 2006 was 696,342 ± 65 kilometers, calculated by timing transits of Mercury across the surface.[12] while some in 2018 measured 695,660 ± 140 kilometers which is consistent with helioseismic estimates.[13] To avoid confusion, International Astronomical Union set the solar radius to exactly 695700 km.[14]

- ^ The best estimate mass is (1.988 475 ± 0.000 092) × 1030 kg.[11] Another estimate mass gave 1.988 420 × 1030 kg (based on the ratio of the mass of Earth to the Sun of 1⁄332946).[15] To simplify the solar mass, International Astronomical Union set it to exactly 1.988 416 × 1030 kg.[14]

- ^ Applying the Stefan–Boltzmann law with a nominal solar effective temperature of 5,772 K:

- .

- ^ Using PMS evolutionary models and a potential higher age of 1 Myr, the luminosity would be lower, and the planet would be smaller. However, this would require for the object to be closer as well, which is unlikely. Another distance estimate to the Orion Nebula Cluster would result in a luminosity 1.14 times lower and also a smaller radius.

- ^ Instead of a photo-evaporating disk it may be an evaporating gaseous globule (EGG). If so, it has a final mass of 2 - 28 MJ.[21]

- ^ A calculated radius thus does not need to be the radius of the (dense) core.

- ^ Proplyd 133-353 is proposed to have formed in a very low-mass dusty cloud or an evaporating gas globule as a second generation of star formation, which can explain both its young age and the presence of its disk.

- ^ [d] [e] [f] [g] [21]

- ^ a b c d e f Based on the estimated temperature and luminosity via the Stefan-Boltzmann law.

- ^ This radius estimate might have been affected by the planet's circumplanetary disk, as the spectrum not necessarily corresponds to a planet photosphere.

- ^ a b Assuming elliptical orbit (most likely)

- ^ a b Assuming circular orbit

- ^ a b c While inner binaries commonly use lower cases, planets also do use lower cases. For the case of 2M1510 inner binary, the binary is used as 2M1510AB.

- ^ minus the disputed planet

- ^ a b Refers to the level of 1 bar atmospheric pressure

Candidates for largest exoplanets

[edit]Exoplanets with uncertain radii

[edit]This list contains planets with uncertain radii that could be below or above the adopted cut-off of 1.6 RJ, depending on the estimate.

| * | Probably brown dwarfs (≳ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

|---|---|

| † | Probably sub-brown dwarfs (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass and location) |

| ← | Probably planets (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

| ? | Status uncertain (inconsistency in age or mass of planetary system) |

| → | Planets with grazing transit, hindering radius determination |

| Artist's impression | |

|---|---|

| Direct imaging telescopic observation | |

| Composite image of direct observations | |

| Artist's impression size comparison | |

| Illustration | Name (Alternates) |

Radius (RJ) |

Key | Mass (MJ) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOI-1408 b | 2.23 ± 0.36,[a] 2.4 ± 0.5,[369] > 1, 1.5,[b][370] |

→ | 1.86 ± 0.02[369] | A large radius of 2.23–2.4 RJ has been derived from transit photometry,[369] but this value is likely inaccurate due to the grazing transit of TOI-1408 b; it transits only part of the star's surface, thus hindering a precise measurement of planet-to-star size ratio.[370] The study revealed a clear transit timing variations (TTV) signal for TOI-1408 b, discovering super-Neptune TOI-1408 c which orbits closer to TOI-1408, and claims that their photodynamical modeling could constrain TOI-1408 b's radius more reliably, which needs to be confirmed.[369] | |

|

SR 12 c (SR 12 (AB) b, ROX 21 c) |

1.6[64] – 2.38 +0.27 −0.32[113] |

? | 13 ± 2[113] | The planet is at the very edge of the deuterium burning limit. This object orbits around SR 12 AB at a separation of 980 AU but has a circumplanetary disk, detected in sub-mm with ALMA.[64] The nature of the disk is unclear: Assuming the disk has only 1 mm grains, the dust mass of the disk is 0.012 M🜨 (0.95 M☾). For a disk only made of 1 μm grains, it would have a dust mass of 0.054 M🜨 (4.4 M☾). The disk also contains gas, as is indicated by the accretion of hydrogen, with the gas mass being on the order of 0.03 MJ (about 9.5 M🜨).[64] Other sources of masses includes 14 +7 −8 MJ,[371] 12 – 15 MJ[372] and 11 ± 3 MJ.[64] |

|

AB Pictoris b (AB Pic b) |

1.57 ± 0.07 – 1.8 ± 0.3,[373] 1.4 – 2.2[77] |

← | 10 ± 1[373] | Previously believed to be a likely brown dwarf, with mass estimates of 13–14 MJ[374] to 70 MJ,[375] its mass is now estimated to be 10±1 MJ, with an age of 13.3+1.1 −0.6 million years.[376] |

| TOI-2193 Ab | > 1.55[c][377] | → | 0.94 ± 0.18[377] | Grazing planet, a large reported radius of 1.77 RJ is unreliable. Whether it is larger than 1.6 RJ is unknown. | |

|

XO-6b | 1.517 ± 0.176[378] – 2.17 ± 0.2[186] | ← | 4.47 ± 0.12[186] | A very puffy Hot Jupiter. Large size needs confirmation due to size discrepancy. |

|

GSC 06214-00210 b | 1.49 +0.10 −0.12 – 2.0,[379] 1.91 ± 0.07[113] |

* | 21 ± 6[32] 15.5 ± 0.5[379] |

Has a circumsubstellar disk found by polarimetry.[66] |

|

Beta Pictoris b (β Pic b) |

1.46 ± 0.01[380] – 1.65 ± 0.06[381] | ← | 11.729 +2.337 −2.135[382] |

First exoplanet to have its rotation rate measured[383][384] and fastest-spinning planet discovered at the equator speed of 19.9 ± 1.0 km/s (12.37 ± 0.62 mi/s) or 71,640 ± 3,600 km/h (44,520 ± 2,240 mph).[385] Beta Pictoris b is suspected to have an exomoon due to the former's predicted obliquity misalignment.[386] |

| HD 135344 Ab (SAO 206463 b) |

1.45 +0.06 −0.03 – 1.60 +0.07 −0.06[387] |

← | ~ 10 +1.4 −1.9[387] |

Youngest directly imaged planet that has fully formed and orbits on Solar System scale. This planet formed in the vicinity of the snowline and later migrated to current position during its formation phase.[387] Part of binary system HD 135344. | |

| TOI-3540 b | > 1.44[c][377] | → | 1.18 ± 0.14[377] | Grazing planet, a large reported radius of 2.10 RJ is unreliable. Whether it is larger than 1.6 RJ is unknown. | |

|

Kappa Andromedae b (κ And b, HR 8976 b) |

1.3 – 1.6[388] | ? | 12.8,[389] 13 +12 −2[390] |

Uncertainties in the system age translate into uncertainties in the object's mass. The discovery paper for Kappa Andromedae b argued that the primary's kinematics are consistent with membership in the Columba association, which would imply a system age of 20 to 50 Myr and a mass of about 12.8 MJ.[389] These results were later questioned by those who argued that the primary star's position on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram favors a much older age of 220 ± 100 Myr, provided that the star, Kaffalmusalsala (Kappa Andromedae), is not a fast rotator viewed pole-on.[391][392] However, direct measurements of the star later showed that Kaffalmusalsala is in fact a rapid rotator viewed pole-on, which is the highest stellar rotational velocity of 283.8 km/s (176.3 mi/s),[393] and yield a best-estimated age of 47 +27 −40 Myr favoring a mass between 13 and 30 MJ. A revised luminosity and detailed empirical comparisons with other substellar objects with known ages favor a mass of 13 +12 −2 MJ.[388] |

|

HD 106906 b | 1.30 ± 0.06 – 1.74 ± 0.06,[394] 1.54 +0.04 −0.05[113] |

† | 11 ± 2[395] | This planet orbits around HD 106906 at the separation of 738 AU, a distance much larger than what is possible for a planet formed within a protoplanetary disk.[396] Observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope strengthened the case for the planet having an unusual orbit that perturbed it from its host star's debris disk causing NASA and several news outlets to compare it to the hypothetical Planet Nine.[397][398][d] It was later found that its carbon-to-oxygen ratio is similar to the stellar association it is located in, suggesting that HD 106906 b could have been captured into the system as a planetary-mass free-floating object. This does not rule out formation in a star-like manner.[403] |

| GSC 08047-00232 b | 1.17 – 1.85[77] | * | 25 ± 10[404] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Converted from 25±4 R🜨.

- ^ estimate

- ^ a b 95% lower limit

- ^ Hypothetical Planet Nine may be challenged by the discovery of 2017 OF201[399] which its orbit is anti-aligned to the calculated orbit of Planet Nine. The existence of 2017 OF201, which also means that there are likely many other similar objects that are just obscured from earth observation, challenges one of the leading arguments for Planet Nine, that its gravity causes trans-Neptunian objects to cluster into a distinct region.[400]

It is suggested hypothetical Planet Nine would have ejected 2017 OF201 from its current orbit over times scales of less than 100 million years, though it could be in a temporary orbit.[399][401]

Nevertheless, it is possible that Planet Nine's existence is still there as the simulations do not disprove Planet Nine.[402]

Unconfirmed exoplanets/objects

[edit]These planets are also larger than 1.6 times the size of the largest planet in the Solar System, Jupiter, but have yet to be confirmed or are disputed.

Note: Some data may be unreliable or incorrect due to unit or conversion errors and some objects are candidate exoplanets such as TOI-7081 b and TOI-7018 b[405]

| * | Probably brown dwarfs (≳ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

|---|---|

| † | Probably sub-brown dwarfs (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass and location) |

| ← | Probably planets (≲ 13 MJ) (based on mass) |

| X | Unclassified object (unknown mass) |

| ↘ | Destroyed planet |

| – | Theoretical planet size restrictions |

| Artist's impression | |

|---|---|

| Direct imaging telescopic observation | |

| Composite image of direct observations | |

| Graphic chart | |

| Rendered image | |

| Illustration | Name (Alternates) (Status) |

Radius (RJ) |

Key | Mass (MJ) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

New born planet limit | ~ 30[406] | – | ≤ 20 (≤ 13)[406] |

Theoretical size limit of a newly-formed planet. |

|

Young Hot Jupiter limit | ~ 20[407] | – | ≤ 10[407] | Theoretical size limit of a newly-formed planet that needed 104 – 105 (10000 – 100000) years to migrate close to the host star, but has not yet interacted with it beforehand. |

|

FU Orionis North b (FU Ori Ab) (unconfirmed) |

~ 9.8[406] (~ 1.0 R☉) |

← | ~ 3[406] | Discovered using a variation of disk kinematics.[408] Tidal disruption and extreme evaporation made the planet radius shrink from the beginning of the burst (14 RJ) in 1937[407] to the present year by ~30 per cent and its mass is around half of its initial mass of 6 MJ.[407][406] |

| UCAC4 174-179953 b (unclassified) |

8.14 ± 0.40[409] (0.84 R☉) |

X | Unknown | Object cannot be classified as brown dwarf or exoplanet without a mass estimate. | |

| UCAC4 220-040923 b (unclassified) |

4.65 ± 0.20[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 223-042828 b (unclassified) |

3.33 ± 0.50[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 185-192986 b (unclassified) |

3.3 ± 0.2[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 118-126574 b (unclassified) |

3.12 ± 0.10[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 171-187216 b (unclassified) |

2.75 ± 0.20[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| KOI-7073 b (unclassified) |

2.699 +0.473 −0.794[410] |

X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 175-188215 b (unclassified) |

2.69 ± 0.50[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 116-118563 b (unclassified) |

2.62 ± 0.10[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| 19g-2-01326 b (unclassified) |

2.29 +0.13 −0.61[411] |

X | Unknown | ||

| SOI-2 b (unclassified) |

2.22[412] | X | Unknown | ||

| TIC 332350266 b (unclassified) |

2.21±3.18[413] | X | Unknown | ||

|

Old Hot Jupiter limit | 2.2[85] | – | > ~0.4[86] | Theoretical limit for hot Jupiters close to a star, that are limited by tidal heating, resulting in 'runaway inflation' |

| TIC 138664795 b (unclassified) |

2.16 ± 0.16[413] | X | Unknown | Object cannot be classified as brown dwarf or exoplanet without a mass estimate. | |

| UCAC4 221-041868 b (unclassified) |

2.1 ± 0.20[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| TOI-496 b (unclassified) |

2.05 +0.63 −0.29[414] |

X | Unknown | ||

|

HD 135344 Bb (SAO 206462 b) (Unconfirmed) |

~2[415][416] | ← | 2[415] | First directly imaged planet that is actively forming within protoplanetary disk, specifically at the root of one of the disk's spiral arms[415][416] in which the structure of the disk is the first one that exhibited a high degree of clarity and was observed using several space telescopes and ground-based telescopes, through an international research program of young stars and of stars with planets.[417] Part of binary system HD 135344. |

| SOI-7 b (unclassified) |

1.96[412] | X | Unknown | Object cannot be classified as brown dwarf or exoplanet without a mass estimate. | |

| UCAC4 121-140615 b (unclassified) |

1.94 ± 0.20[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 123-150641 b (unclassified) |

1.93 ± 0.20[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| TIC 274508785 b (unclassified) |

1.92±2.37[413] | X | Unknown | ||

| W74 b (unclassified) |

1.9[418] | X | Unknown | ||

| TIC 116307482 b (unclassified) |

1.89 ± 1.46[413] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 122-142653 b (unclassified) |

1.85 ± 0.10[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| TIC 77173027 b (unclassified) |

1.84 ± 1.12[413] | X | Unknown | ||

| TOI-159 Ab (unclassified) |

1.80 ± 0.77[419] | X | Unknown | ||

| TIC 82205179 b (unclassified) |

1.76 ± 0.56[413] | X | Unknown | ||

| UCAC4 124-144273 b (unclassified) |

1.71 ± 0.10[409] | X | Unknown | ||

| TOI-710 b (unclassified) |

1.66 ± 1.10[420] | X | Unknown | ||

|

TOI-7081 b (unclassified or unconfirmed) |

1.65 ± 0.05[405] | X | Unknown | While TOI-7081 b cannot be classified as brown dwarf or exoplanet without a mass estimate, the study found TOI-7081 b and TOI-7018 b are puffy but cool Jupiters which may be caused by delayed contraction due to inefficient internal heat transport, where composition gradients or layered convection slow cooling and prolong inflation. Future radial velocity observations can constrain eccentricities and test tidal heating as a possible factor.[405] |

|

CVSO 30 c (PTFO 8-8695 c) (disputed) |

1.63 +0.87 −0.34[421] |

← | 4.7 +5.5 −2.0[421] |

CVSO 30 c was discovered by direct imaging, with a calculated mass equal to 4.7 MJ.[422] However, the colors of the object suggest that it may actually be a background star, such as a K-type giant or a M-type subdwarf.[423] If confirmed in the future, it would be the furthest planet to be directly imaged at a dstance of about 1200 ly. Moreover, the phase of "dips" caused by suspected planet CVSO 30 b had drifted nearly 180 degrees from the expected value, thus ruling out the existence of the planet. CVSO 30 is also suspected to be a stellar binary, with the previously reported planetary orbital period equal to the rotation period of the companion star.[424] |

|

TOI-7018 b (unclassified or unconfirmed) |

1.61 ± 0.04[405] | X | Unknown | While TOI-7018 b cannot be classified as brown dwarf or exoplanet without a mass estimate, the study found TOI-7081 b and TOI-7018 b are puffy but cool Jupiters which may be caused by delayed contraction due to inefficient internal heat transport, where composition gradients or layered convection slow cooling and prolong inflation. Future radial velocity observations can constrain eccentricities and test tidal heating as a possible factor.[405] |

| Exoplanets with known mass of ≥1 MJ but unknown radius | |||||

|

CHXR 73 b (CHXR 73 Ab) (unconfirmed) |

Unknown | ← | 12.6 +8.4 −5.2[425] |

The common proper motion with respect to the host star is not yet proven, however, the probability that CHXR 73 and b are unrelated members of Chamaeleon I is ~0.1%.[425] A radius is not yet published, but could be determined. Other members of the same star-forming region in this list, Cha 110913, CT Cha b, OTS 44, all have radii > 2 RJ. |

|

JuMBO 29 a (unconfirmed) |

Unknown | † | 12.5 + 3[364] | The pair orbit around at the separation by 135 AU.[364] |

| JuMBO 29 b (unconfirmed) |

† | ||||

|

JuMBO 24 a (disputed) |

Unknown | † | 11.5[426] | The pair orbit around at the separation by 28 AU.[426] |

| JuMBO 24 b (disputed) |

† | ||||

|

SLRN-2020 (planet) (ZTF 20aazusyv (planet)) (destroyed) |

Unknown | ↘ | ≲10[427] | Either a former hot Jupiter or a hot Neptune. Third planet observed to be engulfed by its host and first one in an older age star.[428] This planet accreted mass from the star and launched some of this mass away in jets. As the planet orbited closer to the star, the star removed the accreted mass and formed a disk around the star and launched jets.[428] |

|

J1407b ("Super Saturn") (disputed) |

Unknown[a] | † | < 6[429] | First exoplanet discovered with a ring system;[430] its circumplanetary disk or ring system has been frequently compared to that of Saturn's, which has led popular media outlets to dub it as a "Super Saturn"[431][430] First detected by automated telescopes in 2007 when its disk eclipsed the star 1SWASP J1407–39 (J1407) and later discovered in 2010 and announced in 2012.[432] Its status is disputed as while the properties of the ALMA object appear to match those of J1407b, it has only been observed once, making it uncertain whether its motion aligns with the expected direction and speed.[429] Recent studies found J1407b likely does not orbit V1400 Centauri and is instead a free-floating object[433][429] with circumplanetary disk,[432][434] or a large ring system composed of mainly dust.[429] |

|

PDS 70 d (unconfirmed) |

Unknown | ← | 5.2 +3.3 −3.5[435] |

In 2019, a third object was detected 0.12 arcseconds from the star. Its spectrum is very blue, possibly due to star light reflected in dust which could be a feature of the inner disk. The possibility does still exist that this object is a planetary mass object enshrouded by a dust envelope. For this second scenario the mass of the planet would be on the order of a few tens M🜨.[436] In 2025 a team[b] detected Keplerian motion of the candidate. The orbit could be in resonance with the PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c. The spectrum in the infrared is mostly consistent with the star PDS 70, but beyond 2.3 μm an infrared excess was detected. This excess could be produced by the thermal emission of the protoplanet, by circumplanetary dust, variability or contamination. The source may not be a point-like source. The source is therefore interpreted as an outer spiral wake from protoplanet PDS 70 d with a dusty envelope. A feature of the inner disk is an alternative explanation of candidate PDS 70 d.[435] PDS 70 is the second multi-planet system to be directly imaged (after HR 8799). |

|

HR 8799 f (unconfirmed) |

Unknown | ← | 4 – 7[437] | All four confirmed HR 8799 planets orbit inside and outside of dusty disks like the Solar Kuiper belt and asteroid belt, which leaves room for HR 8799 f to be discovered inside the inner disk.[438] It is difficult to find planet(s) inside inner disks as these planets at smaller semi-major axes have much shorter orbital periods according to Kepler's third law. At a separation of ~5 au, a planet in this system would move fast enough that observations taken more than a few months apart would start to blur the planet. Nonetheless, the evidence for HR 8799 f is found by a deep targeted search in the HR 8799 system and recovery of the known HR 8799 planets.[437] HR 8799 is the first multi-planet system to be directly imaged. |

|

V391 Pegasi b (V391 Peg b, HS 2201+2610 b) (unconfirmed) |

Unknown | ← | > 3.2 ± 0.7[437] | First planet candidate to claim to be detected using variable star timing and first candidate planet orbiting around a subdwarf B star. If confirmed, its survival would indicate that planets at Earth-like separations can survive their star's red-giant phase, though this is a much larger planet than Earth (about the same size as Jupiter and Saturn).[439] However, subsequent research found evidence both for and against the exoplanet's existence. Although the planet's existence was not disproven, the case for its existence is now certainly weaker, and the authors stated that it "requires confirmation with an independent method".[440] |

|

Sirius Bb (α CMa Bb, WD 0642-166 b) (uncomfirmed) |

Unknown | ← | 1.5,[441] 0.8 – 2.4[442] | In 1986, the Sirius stellar system emitted a higher than expected level of infrared radiation, as measured by the IRAS space-based observatory. This might be an indication of dust in the system, which is considered somewhat unusual for a binary star.[443][444] The Chandra X-ray Observatory image shows Sirius B outshining Sirius A as an X-ray source,[445] indicating that Sirius B may have its own exoplanet(s). |

|

Jupiter-mass Binary Objects (JuMBOs) (unconfirmed and/or disputed) |

Unknown | † | 0.7 − 13[446] | Total of 42 JuMBO systems among 540 free-floating Jupiter-mass objects of which contains 40 binary systems and 2 triplet systems, discovered in Orion Cluster as of 2025. Their wide separations also differ markedly from typical brown dwarf binaries, which have much closer separations around 4 astronomical units.[447] These JuBO binary pairs have separations ranging from 28 to 384 astronomical units.[446] Current formation theories suggest JuMBOs may form when radiation from massive stars erodes fragmenting pre-stellar cores through a process called photoerosion. In this scenario, Lyman continuum radiation from massive stars drives an ionization shock front into a prestellar core that was already beginning to fragment into a binary system. This process simultaneously compresses the inner layers while evaporating the outer layers, resulting in a very low-mass binary system. The process appears most effective within HII regions created by massive stars, though many observed JuMBOs lie outside these regions in the Orion Nebula Cluster. This distribution suggests the objects may have migrated from their formation sites through dynamical interactions over time.[447] Another study argued that JuMBOs formed in situ, like stars. The JuMBOs most likely form directly alongside stars in the cluster, rather than through ejection from planetary systems or capture events. The other proposed mechanisms - ejection of planet pairs from stars, ejection of planet-moon systems, or capture of free-floating planets - failed to produce enough binaries or required unrealistic initial conditions.[448] The most successful model shows that JuMBOs form best about 0.2 million years after the stars, when the cluster environment has partially stabilized. This timing allows enough JuMBOs to survive to match the observed 8% binary fraction. The model also correctly predicts the observed orbital separations of 25-380 astronomical units and mass distributions. The lack of JuMBOs in older star clusters like Upper Scorpius is explained by their gradual destruction through gravitational interactions over time, with simulations predicting that only about 2% of the original pairs survive after 10 million years.[448] An astronomer found that most JuMBOs did not appear in his sample of substellar objects as the color was consistent with reddened background sources or low signal-to-noise sources with only JuMBO 29 being a good candidate for a binary planetary-mass system.[364] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Its disk spans a radius of ~ 90 million kilometers (~ 1259 RJ).

- ^ presents VLT/SPHERE, VLT/NaCo, VLT/SINFONI and JWST/NIRcam observations

Chronological list of largest exoplanets

[edit]These exoplanets were the largest at the time of their discovery.

Present day: 3 August 2025

| * | Identified to be a probable/confirmed brown dwarf (≳ 13 MJ) or a star (≳ 78.5 MJ) |

|---|---|

| ⇗ | Assumed largest exoplanet, but later identified to be probable/confirmed brown dwarf (≳ 13 MJ) or a star (≳ 78.5 MJ) |

| ↓ | Assumed largest exoplanet, but later identified to be smaller in radius than originally determined |

| ↑ | Not assumed largest exoplanet, but later identified to be larger in radius than originally determined |

| † | Candidate for largest exoplanet (currently or in time span) |

| ? | Status uncertain (inconsistency in age or mass of planetary system) while being candidate for largest exoplanet |

| → | Assumed largest exoplanet, while unconfirmed, later retracted and/or confirmed |

| ← | Largest exoplanet (≲ 13 MJ) at the time |

| – | Largest confirmed exoplanet (in radius and mass), while discovered candidates might be larger |

| # | Non-exoplanets reported for reference |

| Artist's impression | |

|---|---|

| Artist's impression size comparison | |

| Direct Imaging telescopic observation | |

| Transiting telescopic observation | |

| Rendered image | |

| Graphic chart | |

| Discovery/Confirmation observatory | |

| Constellation star chart | |

| Years largest discovered | Illustration | Name (Alternates) |

Radius at that time (RJ) |

Key | Mass (MJ) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 – present |

|

HAT-P-67 Ab | 2.140 ± 0.025[87] | – | 0.45 ± 0.15[87] | A very puffy Hot Jupiter which is among planets with lowest densities of ~0.061 g/cm3. Largest known planet with a precisely measured radius, as of 2025.[87] |

| (2025 – present) |

|

AB Aurigae b (AB Aur b, HD 31293 b) |