Luigi Nono

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

Luigi Nono | |

|---|---|

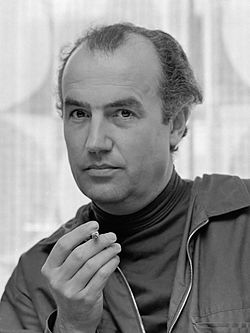

Nono in 1979 | |

| Born | 17 January 1924 Venice, Italy |

| Died | 8 May 1990 (aged 66) Venice |

| Education | |

| Occupation |

|

| Organizations | Darmstadt School |

| Works | List of compositions |

Luigi Nono (Italian pronunciation: [luˈiːdʒi ˈnɔːno]; 29 January 1924 – 8 May 1990) was an Italian avant-garde composer of classical music.

Biography

[edit]

Early years

[edit]Nono, born in Venice, was a member of a wealthy artistic family; his grandfather was a notable painter. Nono began music lessons with Gian Francesco Malipiero at the Venice Conservatory in 1941, where he acquired knowledge of the Renaissance madrigal tradition, amongst other styles. After graduating with a degree in law from the University of Padua, he was given encouragement in composition by Bruno Maderna. Through Maderna, he became acquainted with Hermann Scherchen—then Maderna's conducting teacher—who gave Nono further tutelage and was an early mentor and advocate of his music.

Scherchen presented Nono's first acknowledged work, the Variazioni canoniche sulla serie dell'op. 41 di A. Schönberg in 1950, at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse. The Variazioni canoniche, based on the twelve-tone series of Arnold Schoenberg's Op. 41, including the "Ode-to-Napoleon" hexachord, marked Nono as a committed composer of anti-fascist political orientation.[1] (Variazioni canoniche also used a six-element row of rhythmic values.) Nono had been a member of the Italian Resistance during the Second World War.[2] His political commitment, while allying him with some of his contemporaries at Darmstadt such as Henri Pousseur and in the earlier days Hans Werner Henze, distinguished him from others, including Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Nevertheless, it was with Boulez and Stockhausen that Nono became one of the leaders of the New Music during the 1950s.

1950s and the Darmstadt School

[edit]

A number of Nono's early works were first performed at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse including Tre epitaffi per Federico García Lorca (1951–53), La Victoire de Guernica (1954)—intended, like Picasso's painting, as an indictment of the wartime atrocity—and Incontri (1955). The Liebeslied (1954) was written for Nono's wife-to-be, Nuria Schoenberg (daughter of Arnold Schoenberg), whom he met at the 1953 world première of Moses und Aron in Hamburg. They married in 1955. An atheist,[3] Nono had enrolled as a member of the Italian Communist Party in 1952.[4]

The world première of Il canto sospeso (1955–56) for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra brought Nono international recognition and acknowledgment as a successor to Webern. "Reviewers noted with amazement that Nono's canto sospeso achieved a synthesis—to a degree hardly thought possible—between an uncompromisingly avant-garde style of composition and emotional, moral expression (in which there was an appropriate and complementary treatment of the theme and text)".[4]

If any evidence exists that Webern's work does not mark the esoteric "expiry" of Western music in a pianissimo of aphoristic shreds, then it is provided by Luigi Nono's Il Canto Sospeso ... The 32-year-old composer has proved himself to be the most powerful of Webern's successors. (Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, 26 October 1956).[4]

This work, regarded by Swiss musicologist Jürg Stenzl as one of the central masterpieces of the 1950s,[5] is a commemoration of the victims of Fascism, incorporating farewell letters written by political prisoners before execution. Musically, Nono breaks new ground, not only by the "exemplary balance between voices and instruments"[1] but in the motivic, point-like vocal writing in which words are fractured into syllables exchanged between voices to form floating, diversified sonorities—which may be likened to an imaginative extension of Schoenberg's "Klangfarbenmelodie technique".[6] Nono himself emphasized his lyrical intentions in an interview with Hansjörg Pauli,[7][6] and a connection to Schoenberg's Survivor from Warsaw is postulated by Guerrero.[8] However, Stockhausen, in his 15 July 1957 Darmstadt lecture, "Sprache und Musik" (published the next year in the Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik and, subsequently, in Die Reihe), stated:

In certain pieces in the "Canto", Nono composed the text as if to withdraw it from the public eye where it has no place... In sections II, VI, IX and in parts of III, he turns speech into sounds, noises. The texts are not delivered, but rather concealed in such a regardlessly strict and dense musical form that they are hardly comprehensible when performed.

Why, then, texts at all, and why these texts?

Here is an explanation. When setting certain parts of the letters about which one should be particularly ashamed that they had to be written, the musician assumes the attitude only of the composer who had previously selected the letters: he does not interpret, he does not comment. He rather reduces speech to its sounds and makes music with them. Permutations of vowel-sounds, a, ä, e, i, o, u; serial structure.

Should he not have chosen texts so rich in meaning in the first place, but rather sounds? At least for the sections where only the phonetic properties of speech are dealt with.[9]

Nono took strong exception, and informed Stockhausen that it was "incorrect and misleading, and that he had had neither a phonetic treatment of the text nor more or less differentiated degrees of comprehensibility of the words in mind when setting the text".[11]) Despite Stockhausen's contrite acknowledgment, three years later, in a Darmstadt lecture of 8 July 1960 titled "Text—Musik—Gesang", Nono angrily wrote:

The legacy of these letters became the expression of my composition. And from this relationship between the words as a phonetic-semantic entirety and the music as the composed expression of the words, all of my later choral compositions are to be understood. And it is complete nonsense to conclude, from the analytic treatment of the sound shape of the text, that the semantic content is cast out. The question of why I chose just these texts and no others for a composition is no more intelligent than the question of why, in order to express the word "stupid", one uses the letters arranged in the order s-t-u-p-i-d.[12]

Il canto sospeso has been described as an "everlasting warning";[1] indeed, it is a powerful refutation to the apparent claim made in an often-cited, but out-of-context phrase[13] from philosopher Theodor W. Adorno that "to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric".[14]

Nono was to return to such anti-fascist subject matter again, as in Diario polacco; Composizione no. 2 (1958–59), whose background included a journey through the Nazi concentration camps, and the "azione scenica" Intolleranza 1960, which caused a riot at its première in Venice, on 13 April 1961.[15][2]

It was Nono who, in his 1958 lecture "Die Entwicklung der Reihentechnik",[16] created the expression Darmstadt School to describe the music composed during the 1950s by himself and Pierre Boulez, Bruno Maderna, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and other composers not specifically named by him. He likened their significance to the Bauhaus in the visual arts and architecture.[17]

On 1 September 1959, Nono delivered at Darmstadt a polemically charged lecture written in conjunction with his pupil Helmut Lachenmann, "Geschichte und Gegenwart in der Musik von Heute" ("History and Presence in the Music of Today"), in which he criticised and distanced himself from the composers of chance and aleatoric music, then in vogue, under the influence of American models such as John Cage.[18] Although in a seminar a few days earlier Stockhausen had described himself as "perhaps the extreme antipode to Cage", when he spoke of "statistical structures" at the concert devoted to his works on the evening of the same day, the Marxist Nono saw this in terms of "fascist mass structures" and a violent argument erupted between the two friends.[19] In combination with Nono's strongly negative reaction to Stockhausen's interpretation of text-setting in Il canto sospeso, this effectively ended their friendship until the 1980s, and thus disbanded the "avant-garde trinity" of Boulez, Nono, and Stockhausen.[2]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]Intolleranza 1960 may be viewed as the culmination of the composer's early style and aesthetics.[1] The plot concerns the plight of an emigrant captured in a variety of scenarios relevant to modern capitalist society: working class exploitation, street demonstrations, political arrest and torture, concentration camp internment, refuge, and abandonment. Described as a "stage-action"—Nono explicitly forbade the title of "opera"[20]—it utilizes an array of resources from large orchestra, chorus, tape, and loudspeakers to the "magic lantern" technique drawn from Meyerhold and Mayakovsky theatre practices of the 1920s to form a rich expressionist drama.[1] Angelo Ripellino's libretto consisting of political slogans, poems, and quotations from Brecht and Sartre (including moments of Brechtian alienation), together with Nono's strident, anguished music, fully accords with the anti-capitalist fulmination the composer intended to communicate.[1] The riot at the première in Venice was significantly due to the presence of both left- and right-wing political factions in the audience. Neo-nazis had attempted to disrupt proceedings with stink-bombs, nonetheless failing to prevent the performance ending triumphantly for Nono.[2] Intolleranza is dedicated to Schoenberg.

During the 1960s, Nono's musical activities became increasingly explicit and polemical in their subject, whether that be the warning against nuclear catastrophe (Canti di vita e d'amore: sul ponte di Hiroshima of 1962), the denunciation of capitalism (La Fabbrica Illuminata, 1964), the condemnation of Nazi war criminals in the wake of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials (Ricorda cosi ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz, 1965), or of American imperialism in the Vietnam War (A floresta é jovem e cheja de vida, 1966). Nono began to incorporate documentary material (political speeches, slogans, extraneous sounds) on tape, and a new use of electronics, that he felt necessary to produce the "concrete situations" relevant to contemporary political issues.[1] The instrumental writing tended to conglomerate the 'punctual' serial style of the early 1950s into groups, clusters of sounds—broadstrokes that complimented the use of tape collage.[1] In keeping with his Marxist convictions as 'reinterpreted' through the writings of Antonio Gramsci,[4] he brought this music into universities, trade-unions and factories where he gave lectures and performances. (The title of A floresta é jovem e cheja de vida contains a spelling error, the word "full" is "cheia" in Portuguese, not "cheja".[21]

Nono's second period, commonly thought to have begun after Intolleranza,[1] reaches its apogee in his second "azione scenica", Al gran sole carico d'amore (1972–74)—a collaboration with Yuri Lyubimov, who was then director of the Taganka Theatre in Moscow. In this large-scale stage work, Nono completely dispenses with a dramatic narrative, and presents pivotal moments in the history of Communism and class-struggle "side-by-side" to produce his "theatre of consciousness". The subject matter (as evident from the quotations from manifestos and poems, Marxist classics to the anonymous utterances of workers) deals with failed revolutions; the Paris Commune of 1871, the 1905 Russian Revolution, and the insurgency of militants in 1960s Chile under the leadership of Che Guevara and Tania Bunke.[22] Then extremely topical, Al gran sole offers a multi-lateral spectacle and a moving meditation on the history of twentieth-century communism, as viewed through the prism of Nono's music. It was premiered at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, in 1975.

During this time, Nono visited the Soviet Union where he awakened the interest of Alfred Schnittke and Arvo Pärt, among others, in the contemporary practices of avant-garde composers of the West.[23] Indeed, the 1960s and 70s were marked by frequent travels abroad, lecturing in Latin America, and making the acquaintance of leading left-wing intellectuals and activists. It was to mourn the death of Luciano Cruz, a leader of the Chilean Revolutionary Front, that Nono composed Como una ola de fuerza y luz (1972). Very much in the expressionist style of Al gran sole, with the use of large orchestra, tape and electronics, it became a kind of piano concerto with added vocal commentary.

Nono returned to the piano (with tape) for his next piece, ... sofferte onde serene ... (1976), written for his friend Maurizio Pollini after the common bereavement of two of their relatives (See Nono's Programme note|Col Legno,1994). With this work began a radically new, intimate phase of the composer's development—by way of Con Luigi Dallapiccola for percussion and electronics (1978) to Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima for string quartet (1980). One of Nono's most demanding works (both for performers and listeners), Fragmente-Stille is music on the threshold of silence. The score is interspersed with 53 quotations from the poetry of Hölderlin addressed to his "lover" Diotima, which are to be "sung" silently by the players during performance, striving for that "delicate harmony of inner life" (Hölderlin). A sparse, highly concentrated work commissioned by the Beethovenfest in Bonn, Fragmente-Stille reawakened great interest in Nono's music throughout Germany.[24]

1980s

[edit]

Nono had been introduced to the Venice-based philosopher, Massimo Cacciari (Mayor of Venice from 1993 to 2000), who began to have an increasing influence on the composer's thought during the 1980s.[25] Through Cacciari, Nono became immersed in the work of many German philosophers, including the writings of Walter Benjamin whose ideas on history (strikingly similar to the composer's own) formed the background to the monumental Prometeo—tragedia dell' ascolto (1984/85).[22] The world premiere of the opera was staged in the Church of San Lorenzo, in Venice, on 25 September 1984, conducted by Claudio Abbado, with texts by Massimo Cacciari, lighting by Emilio Vedova, and wooden structures by Renzo Piano.[26][27] Nono's late music is haunted by Benjamin's philosophy, especially the concept of history (Über den Begriff der Geschichte) which is given a central role in Prometeo.

Musically, Nono began to experiment with the new sound possibilities and production at the Experimentalstudio der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung des SWR in Freiburg. There, he devised a new approach to composition and technique, frequently involving the contributions of specialist musicians and technicians to realise his aims.[28] The first fruits of these collaborations were Das atmende Klarsein (1981–82), Diario polacco II (1982)—an indictment against Soviet Cold War tyranny—and Guai ai gelidi mostri (1983). The new technologies allowed the sound to circulate in space, giving this dimension a role no less important than its emission. Such innovations became central to a new conception of time and space.[29] These highly impressive masterworks were partly preparation for what many regard as his greatest achievement.

Prometeo has been described as "one of the best works of the 20th century".[30] After the theatrical excesses of Al gran sole, which Nono later remarked were a "monster of resources",[22] the composer began to think along the lines of an opera or rather a musica per dramma without any visual, stage dimension. In short, a drama in music—"the tragedy of listening"—the subtitle a comment on consumerism today. Hence, in the vocal parts the most simple intervalic procedures (mainly fourths and fifths) resonate amidst a tapestry of harsh, dissonant, microtonal writing for the ensembles.

Prometeo is perhaps the ultimate realisation of Nono's "theatre of consciousness"—here, an invisible theatre in which the production of sound and its projection in space become fundamental to the overall dramaturgy. The architect Renzo Piano designed an enormous 'wooden boat' structure for the première at San Lorenzo church in Venice, whose acoustics must to some extent be reconstructed for each performance. (For the Japanese première at the Akiyoshidai Festival (Shuho), the new concert hall was named 'Prometeo Hall' in Nono's honour, and designed by leading architect Arata Isozaki).[31] The libretto incorporates disparate texts by Hesiod, Hölderlin, and Benjamin (mostly logistically inaudible during performance due to Nono's characteristic deconstruction), which explore the origin and evolution of humanity, as compiled and expanded by Cacciari. In Nono's timeless and visionary context, music and sound predominate over the image and the written word to form new dimensions of meaning and "new possibilities" for listening.

Caminantes, no hay caminos, hay que caminar

In 1985, Nono came across this aphorism ("Travellers, there are no trails – all there is, is travelling") on a wall of the Franciscan monastery near Toledo, Spain, and it played an important role in the rest of his compositions.[32][33][34] As Andrew Clements writes about this aphorism in The Guardian, "It seemed to the composer the perfect expression of his own creative development, and in the last three years of his life he composed a trilogy of works whose titles all derive from that inscription."

Nono's last pieces, such as Caminantes... Ayacucho (1986–87), inspired by a region in southern Peru that experiences extreme poverty and social unrest, La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura (1988–89), and "Hay que caminar" soñando (1989), offer comment on the composer's lifelong quest for political renewal and social justice.

Nono died in Venice in 1990. After his funeral, the German composer Dieter Schnebel remarked that he "was a very great man"[24]—a sentiment widely shared by those who knew him, and those who have come to admire his music.[35] Nono is buried in the San Michele cemetery on the Isola di San Michele, alongside other artists like Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Zoran Mušič and Ezra Pound.

Perhaps the three most important collections of Nono's writings on music, art, and politics (Texte: Studien zu seiner Musik (1975), Ecrits (1993), and Scritti e colloqui (2001)), as well as the texts collected in Restagno,[36] have yet to be translated into English. Other admirers include architect Daniel Libeskind and novelist Umberto Eco (Das Nonoprojekt), for Nono totally reconstructed music and engaged in the most fundamental issues with regards to its expressivity.

The Luigi Nono Archives were established in 1993, through the efforts of Nuria Schoenberg Nono, for the purpose of housing and conserving the Luigi Nono legacy.

Music

[edit]Recordings

[edit]- Nono, Luigi. 1972. Canti di vita d'amore/Per Bastiana/Omaggio a Vedova. Slavka Taskova, soprano; Loren Driscoll, tenor; Saarländisches Rundfunk Sinfonie-Orchester; Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Michael Gielen, cond. Wergo LP WER 60 067. Reissued in 1993 on CD, WER 6229/286 229.

- Nono, Luigi. 1977. Como una ola de fuerza y luz; Epitaffio no. 1, Epitaffio no. 3. Ursula Reinhardt-Kiss, soprano; Giuseppe La Licata, piano; Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig; Herbert Kegel, conductor. Roswitha Trexler, soprano, speaker; Werner Haseleu, baritone, speaker; Rundfunkchor Leipzig; Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig; Horst Neumann, conductor. Eterna LP 8 26 912. Reissued 1994, Berlin Classics 0021412BC.

- Nono, Luigi. 1986. Fragmente—Stille, an Diotima. LaSalle Quartet (Walter Levin and Henry Meyer, violins; Peter Kamnitzer, viola; Lee Fiser, cello). Deutsche Grammophon/PolyGram CD 415 513, reissued in 1993 as 437 720.

- Nono, Luigi. 1988. Il canto sospeso (with Arnold Schoenberg, Moses und Aaron act 1, scene 1, and Bruno Maderna, Hyperion). Ilse Hollweg, soprano; Eva Bornemann, alto; Friedrich Lenz, tenor; Orchestra and Chorus of WDR Cologne (Bernhard Zimmermann, chorus master); Bruno Maderna, conductor. La Nuova Musica 1. Stradivarius STR 10008.

- Nono, Luigi. 1988. Como una ola de fuerza y luz/Contrappunto dialettico alla mente/... sofferte onde serene .... Slavka Taskova (soprano), Maurizio Pollini (piano), Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado, cond. Deutsche Grammophon/PolyGram 423 248. First and third works reissued 2003 (together with Manzoni's Masse: Omaggio a Edgard Varèse) on Deutsche Grammophon/Universal Classics 471 362.

- Nono, Luigi. 1990. Variazioni canoniche; A Carlo Scarpa, architetto ai suoi infiniti possibili; No hay caminos, hay que caminar. Œuvre du XXe siècle. Astrée CD E 8741. [France]: Astrée. Reissued, Montaigne CD MO782132. [France]: Auvidis/Naïve, 2000.

- Nono, Luigi. 1991. A Pierre, dell'azzurro silenzio, inquietum; Quando stanno morendo, diario polacco 2º; Post-prae-ludium per Donau. Roberto Fabricciani, flute; Ciro Sarponi, clarinet; Ingrid Ade, Monika Bayr-Ivenz, Monika Brustmann, sopranos; Susanne Otto, alto; Christine Theus, cello; Roberto Cecconi, conductor; Giancarlo Schiaffini, tuba; Alvise Vidolin, live electronics. Dischi Ricordi CRMCD 1003.

- Nono, Luigi. 1992. Il canto sospeso (with Mahler, Kindertotenlieder and "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" from the Rückert-Lieder). Barbara Bonney, soprano; Susanne Otto, mezzo-soprano; Marek Torzewski, tenor; Susanne Lothar and Bruno Ganz, reciters; Berlin Radio Choir; Berlin Philharmonic; Claudio Abbado, conductor. Sony Classical/SME SK 53360.

- Nono, Luigi. 1992. La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura, Hay que caminar'—soñando. Gidon Kremer and Tatiana Grindenko, violins. Deutsche Grammophon/Universal Classics 474 326.

- Nono, Luigi. 1992. Memento, romance de la guardia civil española (Epitaffio n. 3 per Federico García Lorca); Composizione per orchestra; España en el corazón; Composizione per orchestra n. 2 (Diario polacca); Per Bastiana. Sinfonie Orchester und Chor des Norddeutschen Rundfunks; Orchestra Sinfonica e Coro di Roma della RAI; Sinfonie Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks; Bruno Maderna, conductor. Maderna Edition 17. Arkadia CDCDMAD 027.1.

- Luigi, Nono. 1994. Luigi Nono 1: Fragmente—Stille, an Diotima; "Hay que caminar" soñando. Arditti String Quartet; Irvine Arditti and David Alberman, violins. Arditti Quartet Edition 7. Montaigne MO 7899005.

- Luigi, Nono. 1995. Intolleranza 1960. Ursula Koszut, Kathryn Harries, sopranos; David Rampy, Jerrold van der Schaaf, tenors; Wolfgang Probst, baritone; supporting soloists; Chor der Staatsoper Stuttgart; Staatsorchester Stuttgart; Bernhard Kontarsky, conductor. Notes by Klaus Zehelein. Teldec/WEA Classics 4509–97304.

- Nono, Luigi. 1995. Prometeo. Soloists, Solistenchor Freiburg (chorus master André Richard), Ensemble Modern, conducted by Ingo Metzmacher. Experimentalstudio der Heinrich-Strobel Stiftung des Südwestfunks Freiburg, sound directors André Richard, Hans Peter Haller, Rudolf Strauß, and Roland Breitenfeld. With notes, "Prometeo—Tragedia dell'ascolto", and "Prometeo—Ein Hörleitfaden", by Jürg Stenzl. EMI Classics 7243 5 55209 2 0/CDC 55209.

- Nono, Luigi. 1998. Polifonica—monodia—ritmica; Canti per tredeci; Canciones a Guiomar; "Hay que caminar" soñando. Ensemble UnitedBerlin; Angelika Luz, soprano; United Voices; Peter Hirsch, conductor. Wergo WER 6631/286 631.

- Nono, Luigi. 2000. Orchestral Works and Chamber Music. SWF Symphony Orchestra; Hans Rosbaud and Michael Gielen, conductors; Moscow String Quartet. Programme notes by Wolfgang Löscher. Col Legno WWE 20505.

- Nono, Luigi. 2000. Variazioni canoniche/A Carlo Scarpa, architetto, ai suoi infiniti possibili/No hay caminos, hay que caminar...Andrei Tarkovski. SW German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Michael Gielen, cond. Naïve 782132.

- Nono, Luigi. 2001. Al gran sole carico d'amore. Vocal soloists and chorus of the Staatsoper Stuttgart; Staatsorchester Stuttgart; Lothar Zagrosek, conductor. With notes, "Stories—Luigi Nono's 'Theatre of Consciousness'—Al Gran sole carico d'amore," by Jürg Stenzl. Teldec New Line/Warner Classics 8573–81059–2.

- Nono, Luigi. 2001. Choral Works: Cori di Didone; Da un diario italiano; Das atmende Klarsein. SWR Vokalensemble Stuttgart; Rupert Huber, conductor. Faszination Musik. Hänssler Classic 93.022.

- Nono, Luigi. 2001. Variazioni canoniche sulla serie dell' op. 41 di A. Schönberg; Varianti; No hay caminos, hay que caminar—Andrej Tarkowskij; Incontri. Col Legno WWE 1CD 31822. Mark Kaplan, violin. Sinfonieorchester Basel, Mario Venzago, cond. [Munich]: Col Legno.

- Nono, Luigi. 2004. Io, frammento da Prometeo, Das atmende Klarsein. Katia Plaschka, Petra Hoffmann, Monika Bair-Ivenz, Roberto Fabbriciani, Ciro Scarponi; Solistenchor Freiburg, Experimentalstudio Freiburg, André Richard. col legno 2 SACD 20600 (Helikon Harmonia Mundi).

- Nono, Luigi. 2006. 20 Jahre Inventionen V: Quando stanno morendo. Diario polacco n. 2; Canciones a Guiomar; Omaggio a Emilio Vedova. Ingrid Ade, Monika Bar-Ivenz, Halina Nieckarz, sopranos; Bernadette Manca di Nissa, alto; Roberto Fabbriciani, bass flute; Frances-Marie Uitti, violoncello; Arturo Tamayo, conductor; Experimentalstudio der Heinrich Strobel Stiftung; Luigi Nono, Hans Peter Haller, sound direction; Rudolf Strauss, Bernd Noll, technicians; Alvise Vidolin, assistant (Quando stanno morendo); Eldegard Neubert-Imm, soprano; Ars Nova Ensemble Berlin; Peter Schwartz, conductor (Canciones a Guiomar); tape (Omaggio a Emilio Vedova). Edition RZ 4006.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Annibaldi 1980.

- ^ a b c d Schoenberg-Nono 2005.

- ^ Nattiez, Bent, Dalmonte, and Baroni 2001–2005, p. 424.

- ^ a b c d Flamm 1995.

- ^ Stenzl 1986b.

- ^ a b Flamm 1995, p. IX.

- ^ Pauli 1971.

- ^ Guerrero 2006.

- ^ Stockhausen 1964, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Leeuw 2005, p. 177.

- ^ Stockhausen 1964, p. 49.

- ^ Nono 1975, pp. 41–60.

- ^ Hofmann 2005.

- ^ Adorno 1981, p. 34.

- ^ Steinitz 1995.

- ^ Nono 1975, pp. 21–33.

- ^ Nono 1975, p. 30.

- ^ Nono 1975, pp. 34–40.

- ^ Kurtz 1992, p. 98.

- ^ Stenzl 1999.

- ^ Davezies 1965, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c Stenzl 1995.

- ^ Ivashkin 1996, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Loescher 2000.

- ^ Carvalho 1999.

- ^ "Group Exhibition | Prometheus: A Tragedy about Listening". Thaddaeus Ropac. Retrieved 2024-06-22.

- ^ "Luigi Nono Prometeo, Tragedia dell'ascolto" (PDF). col-legno.com.

- ^ Fabbriciani 1999.

- ^ Pestalozza 1992.

- ^ Beyst 2003.

- ^ Newhouse 2012, p. 50.

- ^ Clements 2007.

- ^ McHard 2008, p. 243.

- ^ Griffiths 2004, p. 551.

- ^ Davismoon 1999a, pp. 17–30.

- ^ Restagno 1987.

Cited sources

[edit]- Adorno, Theodor W. 1955. "Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft" (1951), in his Prismen: Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Adorno, Theodor W. 1981. Prisms. Translated from the German by Samuel and Shierry Weber. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought 4. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01064-1 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-262-51025-7 (pbk) [English translation of (Adorno 1955)].

- Annibaldi, Claudio. 1980. "Nono, Luigi". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. Washington, D.C.: Grove's Dictionaries of Music.

- Beyst, Stefan. 2003. "Nono's Il Prometeo—a Revolutionary Swan Song" (Online).

- Carvalho, Mário Vieira de. 1999. "Quotation and Montage in the Work of Luigi Nono". Contemporary Music Review 18, part 2:37–85.

- Clements, Andrew. 2007. "Nono: No Hay Caminos, Hay Que Caminar ... Andrei Tarkovsky etc." The Guardian (30 November).

- Davezies, Robert. 1965. Les Angolais. Grands Documents 21. [Paris]: Éditions de Minuit.

- Davismoon, Stephen (ed.). 1999a. Luigi Nono (1924–1990): The Suspended Song. Contemporary Music Review 18, part 1. [Netherlands] : Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5755-112-3.

- Fabbriciani, Roberto. 1999. "Walking with Gigi". Contemporary Music Review 18, no. 1:7–15.

- Flamm, Christoph. 1995. "Preface" to Luigi Nono, Il canto sospeso (score), 13–28. London: Eulenburg Edition.

- Griffiths, Paul. 2004. The Penguin Companion to Classical Music. London, New York, Victoria, Toronto, New Delhi, Auckland, and Rosebank: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-100924-7.

- Guerrero, Jeannie Ma. 2006. "Serial Intervention in Nono's Il canto sospeso". Music Theory Online 12, no. 1 (February)].

- Hofmann, Klaus. 2005. "Poetry after Auschwitz—Adorno's Dictum". German Life and Letters 58, no. 2:182–194.

- Ivashkin, Alexander. 1996. Alfred Schnittke. Phaidon 20th Century Composers, edited by Norman Lebrecht. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3169-5.

- Kurtz, Michael. 1992. Stockhausen: A Biography, translated by Richard Toop. London: Faber and Faber.

- Leeuw, Ton de. 2005. Music of the Twentieth Century: A Study of Its Elements and Structure, translated from the Dutch by Stephen Taylor. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-765-4.

- Loescher, Wolfgang. 2000. Luigi Nono (1924–1990), liner notes to Luigi Nono, Orchestral and Chamber Music. Col Legno CD WWE 1CD 20505.

- McHard, James L. 2008. The Future of Modern Music, third edition. Livonia, Michigan: Iconic Press. ISBN 978-0-9778195-2-2.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques, Margaret Bent, Rossana Dalmonte, and Mario Baroni. 2001–2005. Enciclopedia della musica, vol. 1 (of 5). Turin: G. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-15840-8.

- Newhouse, Victoria. 2012. Site and Sound: The Architecture and Acoustics of New Opera Houses and Concert Halls. New York: The Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-281-3.

- Nono, Luigi. 1975. Texte, Studien zu seiner Musik, edited by Jürg Stenzl. Zürich: Atlantis. ISBN 978-3-7611-0456-9.

- Pauli, Hansjörg. 1971. Für wen komponieren Sie eigentlich? Reihe Fischer, vol. F 16. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

- Pestalozza, Luigi. 1992. Nono: La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura, "Hey que caminar" sonando, Deutsche Grammophon.

- Restagno, Enzo. 1987 Nono / autori vari. Biblioteca di cultura musicale: Autori e opere. Torino: EDT/Musica. ISBN 978-88-7063-048-0 [Includes an interview with Nono (German translation published in Nono and Restagno 2004) and selections from his writings.]

- Schoenberg-Nono, Nuria. 2005. Interview. "Music Matters", BBC Radio 3 (24 April).

- Steinitz, Richard. 1995. "Luigi Nono". Introduction, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival brochure.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 1986b. "Luigi Nono" [short biography], English translation by John Patrick Thomas. Unpaginated liner notes for Luigi Nono, Fragmente – Stille, an Diotima, Deutsche Grammophon CD 415 513-2.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 1995. "Prometeo—Tragedia dell'ascolto". Liner notes for the recording of Prometeo, EMI Classics, 2-CD set (7243 5 55209 2 X).

- Stenzl, Jürg. 1999. "Stories/ Luigi Nono's 'theatre of consciousness', Al gran sole carico d'amore". Teldec New Line 8573-81059-2

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1964. "Music and Speech", translated by Ruth Koenig. Die Reihe 6 (English edition): 40–64. Original German version, as "Musik und Sprache", Die Reihe 6 (1960): 36–58. The portion on Nono's Il canto sospeso reprinted as "Luigi Nono: Sprache und Musik [sic] II", in Stockhausen, Texte 2. Cologne: Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, 1964.

Further reading

[edit]- Assis, Paulo de. 2006. Luigi Nonos Wende: zwischen Como una ola fuerza y luz und sofferte onde serene. 2 vols. Hofheim: Wolke. ISBN 978-3-936000-62-7.

- Bailey, Kathryn. 1992. "'Work in Progress': Analysing Nono's Il canto sospeso." Music Analysis 11, nos. 2–3 (July–October): 279–334.

- Borio, Gianmario. 2001a. "Tempo e ritmo nelle composizioni seriali di Luigi Nono." Schweizer Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft/Annales suisses de musicologie/Annuario svizzero di musicologia no. 21:79–136.

- Borio, Gianmario. 2001b. "Nono, Luigi." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan.

- Davismoon, Stephen (ed.). 1999b. Luigi Nono (1924–1990): Fragments and Silence. Contemporary Music Review 18, part 2. [Netherlands] : Harwood Academic Publishers.

- De Benedictis, Angela Ida and Rizzardi, Veniero. 2023. Luigi Nono and the Development of Serial Technique, in The Cambridge Companion to Serialism, edited by Martid Iddon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Feneyrou, Laurent. 2002. Il canto sospeso de Luigi Nono: musique & analyse. Paris: M. de Maule. ISBN 978-2-87623-106-1.

- Feneyrou, Laurent. 2003. "Vers l'incertain: Une introduction au Prometeo de Luigi Nono." Analyse musicale no. 46 (February).

- Fox, Christopher. 1999. "Luigi Nono and the Darmstadt School: Form and Meaning in the Early Works (1950–1959)". Contemporary Music Review 18, no. 2: 111–130.

- Frobenius, Wolf. 1997. "Luigi Nonos Streichquartett Fragmente—Stille, An Diotima." Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 54, no. 3:177–193.

- Guerrero, Jeannie Ma. 2009. "The Presence of Hindemith in Nono's Sketches: A New Context for Nono's Music". The Journal of Musicology 26, no. 4:481–511.

- Hermann, Matthias. 2000. "Das Zeitnetz als serielles Mittel formaler Organisation: Untersuchungen zum 4. Satz aus Il Canto Sospeso von Luigi Nono". In Musiktheorie: Festschrift für Heinrich Deppert zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Wolfgang Budday, Heinrich Deppert, and Erhard Karkoschka, 261–275. Tutzing: Hans Schneider. ISBN 978-3-7952-1005-2.

- Hopkins, Bill. 1978. "Luigi Nono: The Individuation of Power and Light." The Musical Times 99, no. 1623 (May): 406–409.

- Huber, Nicolaus A. 1981. "Luigi Nono: Il canto sospeso VIa, b—Versuch einer Analyse mit Hilfe dialektischer Montagetechniken". In Musik-Konzepte 20 (Luigi Nono), edited by Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn, 58–79. Munich: Edition text + kritik. Reprinted in Nicolaus Huber, Durchleuchtungen: Texte zur Musik 1964–1999, edited by Josef Häusler, 118–139. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 2000. ISBN 978-3-7651-0328-5.

- Huber, Nicolaus A. 2000. "Über einige Beziehungen von Politik und Kompositionstechnik bei Nono". In Nicolaus Huber, Durchleuchtungen: Texte zur Musik 1964–1999, edited by Josef Häusler, 57–66. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 978-3-7651-0328-5.

- Jabès, Edmond, Luigi Nono, Massimo Cacciari, and Nils Röller. 1995. Migranten, interviews, edited and translated by Nils Röller. Internationaler Merve-Diskurs 194. Berlin: Merve. ISBN 978-3-88396-126-2.

- Kolleritsch, Otto (ed.). 1990. Die Musik Luigi Nonos. Studien zur Wertungsforschung 24. Vienna: Universal Edition. ISBN 978-3-7024-0198-6.

- Licata, Thomas. 2002. "Luigi Nono's Omaggio a Emilio Vedova". In Electroacoustic Music: Analytical Perspectives, edited by Thomas Licata, 73–89. Contributions to the Study of Music and Dance 63. Westport, Connecticut & London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31420-9.

- Luigi Nono Archive. n.d. Venice.

- Luigi Nono Exhibition. n.d. "Gigi e Nuria, il racconto di un amore in musica", Federazione CEMAT. Sonora|Ritratti.

- Mann, Jackson Albert. 2019. A Musician For The Class Struggle. Jacobin. Accessed 8 August 2019.

- Metzger, Heinz-Klaus, and Rainer Riehn, eds. 1981. Luigi Nono. Musik-Konzepte 20. Munich: Edition Text+Kritik. ISBN 978-3-88377-072-7.

- Motz, Wolfgang. 1998. "Konstruktion und Ausdruck: Analytische Betrachtungen zu Il canto sospeso (1955/56) von Luigi Nono". Die Musikforschung 51, no. 3:376–377.

- Nielinger, Carola. 2006. "The Song Unsung: Luigi Nono's Il canto sospeso." Journal of the Royal Musical Association 131, no. 1:83–150.

- Nono, Luigi. 1993. Ecrits, réunis, présentés et annotés par Laurent Feneyrou; traduits sous la direction de Laurent Feneyrou. Musique/passé/présent. [Paris]: Christian Bourgois Editeur. ISBN 978-2-267-01152-4.

- Nono, Luigi. 2001. Scritti e colloqui. 2 vols. Edited by Angela Ida De Benedictis and Veniero Rizzardi. Milan: Ricordi; Lucca: LIM.

- Nono, Luigi, and Enzo Restagno. 2004. Incontri: Luigi Nono im Gespräch mit Enzo Restagno, Berlin, März 1987. Edited by Matteo Nanni and Rainer Schmusch. Hofheim: Wolke. ISBN 978-3-936000-32-0 [German translation of an interview originally published, in Italian, in Restagno 1987.]

- Nono, Luigi. 2018. Nostalgia for the Future. Luigi Nono's Selected Writings and Interviews, Edited by Angela Ida De Benedictis and Veniero Rizzardi. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Ozorio, Anne. 2008a. Review of Luigi Nono, Prometeo: Tragedia dell'ascolto (COL LEGNO SACD – WWE 2SACD 20605). Musicweb International (April). Accessed 15 August 2010.

- Ozorio, Anne. 2008b. Review of Luigi Nono, Prometeo: Tragedia dell'ascolto. Performances at Royal Festival Hall, London, May 2008. Musicweb International (June). Accessed 15 August 2010.

- Pon, Gundaris. 1972. "Webern and Luigi Nono: The Genesis of a New Compositional Morphology and Syntax." Perspectives of New Music, 10, no. 2 (Spring–Summer): 111–119.

- Schaller, Erika. 1997. Klang und Zahl: Luigi Nono: serielles Komponieren zwischen 1955 und 1959. Saarbrücken: PFAU.ISBN 978-3-930735-62-4.

- Shimizu, Minoru. 2001. "Verständlichkeit des Abgebrochenen: Musik und Sprache bei Nono im Kontrast zu Stockhausen". In Aspetti musicali: Musikhistorische Dimensionen Italiens 1600 bis 2000—Festschrift für Dietrich Kämper zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Christoph von Blumröder, Norbert Bolin, and Imke Misch, 315–319. Köln-Rheinkassel: Dohr. ISBN 978-3-925366-83-3.

- Spangemacher, Friedrich. 1983. Luigi Nono, die elektronische Musik: historischer Kontext, Entwicklung, Kompositionstechnik. Forschungsbeiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 29. Regensburg: G. Bosse. ISBN 978-3-7649-2260-3.

- Spree, Hermann. 1992. Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima: ein analytischer Versuch zu Luigi Nonos Streichquartett. Saarbrücken : PFAU. ISBN 978-3-928654-06-7.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 1986a. "Luigi Nono: Fragmente – Stille, an Diotima" / "Fragments – Stillness, for Diotima", English translation by C. Stenzl and L. Pon. Unpaginated liner notes for Luigi Nono, Fragmente – Stille, an Diotima, Deutsche Grammophon CD 415 513–2.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 1998. Luigi Nono. Rowohlts Monographien 50582. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-499-50582-9.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 2002a. "Luigi Nono: Il canto sospeso für Sopran-, Alt- und Tenor-Solo, gemischten Chor und Orchester, 1955/56". In Musikerhandschriften: Von Heinrich Schütz bis Wolfgang Rihm, edited by Günter Brosche, 160–161. Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-010501-6.

- Stenzl, Jürg. 2002b. Luigi Nono: Werkzeichnis, Bibliographie seiner Schriften und der Sekundärliteratur, Diskographie, Filmographie, Bandarchiv, third edition. Salzburg: Jürg Stenzl.

- Stoïanova, Ivanka. 1987. "Testo—musica—senso: Il canto sospeso". In Nono, edited bu E. Restagno, 128–135. Turin: Edizioni di Torino.

- Stoïanova, Ivanka. 1998. "L'exercice de l'espace et du silence dans la musique de Luigi Nono". In L'espace: Musique/philosophie, edited by Jean-Marc Chouvel and Makis Solomos, 425–438. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7384-6593-1.

- Zehelein, Klaus. 1993. "Intolleranza 1960—Music at the Crossroads". Liner notes for Teldec CD 4509 97304–2

Obituaries

[edit]- Osmond-Smith, David (11 May 1990). "Notes of dissent". The Guardian. London. p. 39. Retrieved 30 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Luigi Nono, Italian composer". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. 14 May 1990. p. 36. Retrieved 30 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Luigi Nono (composer) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Luigi Nono (composer) at Wikimedia Commons

- Archivio Luigi Nono, Venice, Italy, including list of dated works, biography and discography

- Nonoprojekt

- The Ensemble Sospeso – Luigi Nono

- "Luigi Nono (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- Nono's il prometeo: a revolutionary's swansong

- Nono's 'Quando stanno morendo': cries, whispers and voices celestial'

- 'A Weak Power Thinking Bringing to a Halt' review by John Wollaston, dated 28 May 2008, of London performance of Prometeo

- "Nono's Shrug at Immortality: La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura" and "Nono at the Close: Hay que caminar„ soñando", lafolia.com

- Virtuelle Fachbibliothek Musikwissenschaft Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | Nonoprojekt

KSF

KSF