Marine microorganisms

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 82 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 82 min

| Part of a series of overviews on |

| Marine life |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism (or microbe) is any microscopic living organism or virus, which is invisibly small to the unaided human eye without magnification. Microorganisms are very diverse. They can be single-celled[1] or multicellular and include bacteria, archaea, viruses, and most protozoa, as well as some fungi, algae, and animals, such as rotifers and copepods. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify viruses as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.[2][3]

Marine microorganisms have been variously estimated to make up about 70%,[4] or about 90%,[5][6] of the biomass in the ocean. Taken together they form the marine microbiome. Over billions of years this microbiome has evolved many life styles and adaptations and come to participate in the global cycling of almost all chemical elements.[7] Microorganisms are crucial to nutrient recycling in ecosystems as they act as decomposers. They are also responsible for nearly all photosynthesis that occurs in the ocean, as well as the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients and trace elements.[8] Marine microorganisms sequester large amounts of carbon and produce much of the world's oxygen.

A small proportion of marine microorganisms are pathogenic, causing disease and even death in marine plants and animals.[9] However marine microorganisms recycle the major chemical elements, both producing and consuming about half of all organic matter generated on the planet every year. As inhabitants of the largest environment on Earth, microbial marine systems drive changes in every global system.

In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all life on the planet, including the marine microorganisms.[10] Despite its diversity, microscopic life in the oceans is still poorly understood. For example, the role of viruses in marine ecosystems has barely been explored even in the beginning of the 21st century.[11]

Overview

[edit]

Microorganisms make up about 70% of the marine biomass.[4] A microorganism, or microbe, is a microscopic organism too small to be recognised adequately with the naked eye. In practice, that includes organisms smaller than about 0.1 mm.[12]: 13

Such organisms can be single-celled[1] or multicellular. Microorganisms are diverse and include all bacteria and archaea, most protists including algae, protozoa and fungal-like protists, as well as certain microscopic animals such as rotifers. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify viruses as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.[2][3]

Microorganisms are crucial to nutrient recycling in ecosystems as they act as decomposers. Some microorganisms are pathogenic, causing disease and even death in plants and animals.[9] As inhabitants of the largest environment on Earth, microbial marine systems drive changes in every global system. Microbes are responsible for virtually all the photosynthesis that occurs in the ocean, as well as the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients and trace elements.[8]

| Marine microorganisms | |

While recent technological developments and scientific discoveries have been substantial, we still lack a major understanding at all levels of the basic ecological questions in relation to the microorganisms in our seas and oceans. These fundamental questions are:

1. What is out there? Which microorganisms are present in our seas and oceans and in what numbers do they occur?

2. What are they doing? What functions do each of these microorganisms perform in the marine environment and how do they contribute to the global cycles of energy and matter?

3. What are the factors that determine the presence or absence of a microorganism and how do they influence biodiversity and function and vice versa?

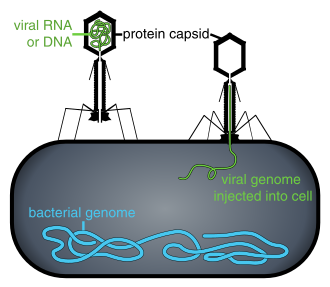

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of viruses in marine ecosystems.[13] Most marine viruses are bacteriophages, which are harmless to plants and animals, but are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.[14] They infect and destroy bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, and are the most important mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth.[15] Viral activity may also contribute to the biological pump, the process whereby carbon is sequestered in the deep ocean.[16]

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes.[17] Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.[18][19]

Microscopic organisms live throughout the biosphere. The mass of prokaryote microorganisms — which includes bacteria and archaea, but not the nucleated eukaryote microorganisms — may be as much as 0.8 trillion tons of carbon (of the total biosphere mass, estimated at between 1 and 4 trillion tons).[20] Single-celled barophilic marine microbes have been found at a depth of 10,900 m (35,800 ft) in the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot in the Earth's oceans.[21][22] Microorganisms live inside rocks 580 m (1,900 ft) below the sea floor under 2,590 m (8,500 ft) of ocean off the coast of the northwestern United States,[21][23] as well as 2,400 m (7,900 ft; 1.5 mi) beneath the seabed off Japan.[24] The greatest known temperature at which microbial life can exist is 122 °C (252 °F) (Methanopyrus kandleri).[25] In 2014, scientists confirmed the existence of microorganisms living 800 m (2,600 ft) below the ice of Antarctica.[26][27] According to one researcher, "You can find microbes everywhere — they're extremely adaptable to conditions, and survive wherever they are."[21] Marine microorganisms serve as "the foundation of all marine food webs, recycling major elements and producing and consuming about half the organic matter generated on Earth each year".[28][29]

Marine viruses

[edit]

including viral infection of bacteria, phytoplankton and fish[30]

A virus is a small infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of other organisms. Viruses can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.[31]

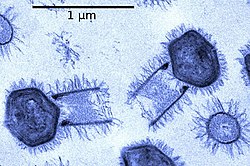

When not inside an infected cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles. These viral particles, also known as virions, consist of two or three parts: (i) the genetic material (genome) made from either DNA or RNA, long molecules that carry genetic information; (ii) a protein coat called the capsid, which surrounds and protects the genetic material; and in some cases (iii) an envelope of lipids that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms for some virus species to more complex structures for others. Most virus species have virions that are too small to be seen with an optical microscope. The average virion is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity.[32] Viruses are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce, and evolve through natural selection. However, they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life"[33] and as replicators.[34]

Viruses are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved.[35] The origin of viruses is unclear because they do not form fossils, so molecular techniques have been used to compare the DNA or RNA of viruses and are a useful means of investigating how they arose.[36]

Viruses are now recognised as ancient and as having origins that pre-date the divergence of life into the three domains.[37]

Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life or organic structures that interact with living organisms.[34] They are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly, and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics such as a cellular structure generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as replicators[34] and as "organisms at the edge of life".[33]

Phages

[edit]

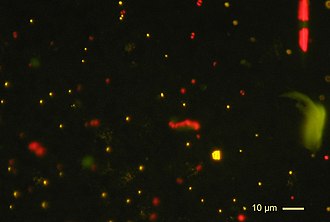

Bacteriophages, often just called phages, are viruses that parasite bacteria and archaea. Marine phages parasite marine bacteria and archaea, such as cyanobacteria.[38] They are a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments, because their hosts, bacteria, are typically the numerically dominant cellular life in the sea. Generally there are about 1 million to 10 million viruses in each mL of seawater, or about ten times more double-stranded DNA viruses than there are cellular organisms,[39][40] although estimates of viral abundance in seawater can vary over a wide range.[41][42] For a long time, tailed phages of the order Caudovirales seemed to dominate marine ecosystems in number and diversity of organisms.[38] However, as a result of more recent research, non-tailed viruses appear to be dominant in multiple depths and oceanic regions, followed by the Caudovirales families of myoviruses, podoviruses, and siphoviruses.[43] Phages belonging to the families: Corticoviridae,[44] Inoviridae,[45] Microviridae,[46] and Autolykiviridae[47][48][49][50] are also known to infect diverse marine bacteria.

There are also archaean viruses which replicate within archaea: these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes.[51][52] These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales and Thermoproteales.[53]

Role of viruses

[edit]Microorganisms make up about 70% of the marine biomass.[4] It is estimated viruses kill 20% of this biomass each day and that there are 15 times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal blooms,[40] which often kill other marine life.[54] The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.[16]

Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution.[32] It is thought that viruses played a central role in the early evolution, before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth.[55] Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity on Earth.[16]

Giant viruses

[edit]

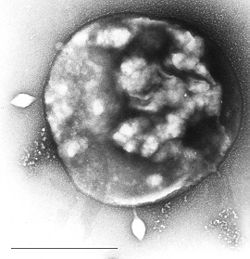

Viruses normally range in length from about 20 to 300 nanometers. This can be contrasted with the length of bacteria, which starts at about 400 nanometers. There are also giant viruses, often called giruses, typically about 1000 nanometers (one micron) in length. All giant viruses belongto phylum Nucleocytoviricota (NCLDV), together with poxviruses. The largest known of these is Tupanvirus. This genus of giant virus was discovered in 2018 in the deep ocean as well as a soda lake, and can reach up to 2.3 microns in total length.[56]

The discovery and subsequent characterization of giant viruses has triggered some debate concerning their evolutionary origins.[57] The two main hypotheses for their origin are that either they evolved from small viruses, picking up DNA from host organisms, or that they evolved from very complicated organisms into the current form which is not self-sufficient for reproduction.[58] What sort of complicated organism giant viruses might have diverged from is also a topic of debate. One proposal is that the origin point actually represents a fourth domain of life,[59][60] but this has been largely discounted.[61][62]

Prokaryotes

[edit]Marine bacteria

[edit]

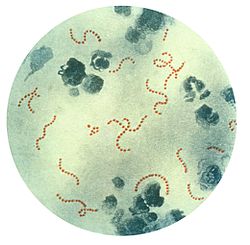

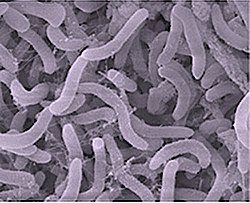

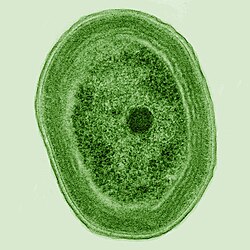

Bacteria constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a number of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals. Bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste,[63] and the deep portions of Earth's crust. Bacteria also live in symbiotic and parasitic relationships with plants and animals.

Once regarded as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes, bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryotes, bacterial cells do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbour membrane-bound organelles. Although the term bacteria traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called Bacteria and Archaea.[64]

The ancestors of modern bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago. For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life.[65][66] Although bacterial fossils exist, such as stromatolites, their lack of distinctive morphology prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage.[67] Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes. Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea.[68][69] This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacterial symbionts to form either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes, which are still found in all known Eukarya. Later on, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacterial-like organisms. This led to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants. There are also some algae that originated from even later endosymbiotic events. Here, eukaryotes engulfed a eukaryotic algae that developed into a "second-generation" plastid.[70][71] This is known as secondary endosymbiosis.

-

The marine Thiomargarita namibiensis, largest known bacterium

-

The chloroplasts of glaucophytes have a peptidoglycan layer, evidence suggesting their endosymbiotic origin from cyanobacteria.[72]

-

The bacterium Marinomonas arctica grows inside Arctic sea ice at subzero temperatures

Pelagibacter ubique and its relatives may be the most abundant organisms in the ocean, and it has been claimed that they are possibly the most abundant bacteria in the world. They make up about 25% of all microbial plankton cells, and in the summer they may account for approximately half the cells present in temperate ocean surface water. The total abundance of P. ubique and relatives is estimated to be about 2 × 1028 microbes.[73] However, it was reported in Nature in February 2013 that the bacteriophage HTVC010P, which attacks P. ubique, has been discovered and "it probably really is the commonest organism on the planet".[74][75]

The largest known bacterium, the marine Thiomargarita namibiensis, can be visible to the naked eye and sometimes attains 0.75 mm (750 μm).[76][77]

Marine archaea

[edit]

The archaea (Greek for ancient[79]) constitute a domain and kingdom of single-celled microorganisms. These microbes are prokaryotes, meaning they have no cell nucleus or any other membrane-bound organelles in their cells.

Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, but this classification is outdated.[80] Archaeal cells have unique properties separating them from the other two domains of life, Bacteria and Eukaryota. The Archaea are further divided into multiple recognized phyla. Classification is difficult because the majority have not been isolated in the laboratory and have only been detected by analysis of their nucleic acids in samples from their environment.

Archaea and bacteria are generally similar in size and shape, although a few archaea have very strange shapes, such as the flat and square-shaped cells of Haloquadratum walsbyi.[81] Despite this morphological similarity to bacteria, archaea possess genes and several metabolic pathways that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably the enzymes involved in transcription and translation. Other aspects of archaeal biochemistry are unique, such as their reliance on ether lipids in their cell membranes, such as archaeols. Archaea use more energy sources than eukaryotes: these range from organic compounds, such as sugars, to ammonia, metal ions or even hydrogen gas. Salt-tolerant archaea (the Haloarchaea) use sunlight as an energy source, and other species of archaea fix carbon; however, unlike plants and cyanobacteria, no known species of archaea does both. Archaea reproduce asexually by binary fission, fragmentation, or budding; unlike bacteria and eukaryotes, no known species forms spores.

Archaea are particularly numerous in the oceans, and the archaea in plankton may be one of the most abundant groups of organisms on the planet. Archaea are a major part of Earth's life and may play roles in both the carbon cycle and the nitrogen cycle. Thermoproteota (also known as eocytes or Crenarchaeota) are a phylum of archaea thought to be very abundant in marine environments and one of the main contributors to the fixation of carbon.[82]

-

Eocytes may be the most abundant of marine archaea

-

Halobacteria, found in water nearly saturated with salt, are now recognised as archaea.

-

Flat, square-shaped cells of the archaea Haloquadratum walsbyi

-

Methanosarcina barkeri, a marine archaea that produces methane

-

Thermophiles, such as Pyrolobus fumarii, survive well over 100 °C

Eukaryotes

[edit]All living organisms can be grouped as either prokaryotes or eukaryotes. Life originated as single-celled prokaryotes and later evolved into the more complex eukaryotes. In contrast to prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells are highly organised. Prokaryotes are the bacteria and archaea, while eukaryotes are the other life forms — protists, plants, fungi and animals. Protists are usually single-celled, while plants, fungi and animals are usually multi-celled.

It seems very plausible that the root of the eukaryotes lie within archaea; the closest relatives nowadays known may be the Heimdallarchaeota phylum of the proposed Asgard superphylum. This theory is a modern version of a scenario originally proposed in 1984 as Eocyte hypothesis, when Thermoproteota were the closest known archaeal relatives of eukaryotes then. A possible transitional form of microorganism between a prokaryote and a eukaryote was discovered in 2012 by Japanese scientists. Parakaryon myojinensis is a unique microorganism larger than a typical prokaryote, but with nuclear material enclosed in a membrane as in a eukaryote, and the presence of endosymbionts. This is seen to be the first plausible evolutionary form of microorganism, showing a stage of development from the prokaryote to the eukaryote.[83][84]

Marine protists

[edit]Protists are eukaryotes that cannot be classified as plants, fungi or animals. They are usually single-celled and microscopic. Life originated as single-celled prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) and later evolved into more complex eukaryotes. Eukaryotes are the more developed life forms known as plants, animals, fungi and protists. The term protist came into use historically as a term of convenience for eukaryotes that cannot be strictly classified as plants, animals or fungi. They are not a part of modern cladistics, because they are paraphyletic (lacking a common ancestor).

By trophic mode

[edit]Protists can be broadly divided into four groups depending on whether their nutrition is plant-like, animal-like, fungal-like,[85] or a mixture of these.[86]

Protists according to how they get food

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of protist | Description | Example | Some other examples | ||||

| Plant-like | Autotrophic protists that make their own food without needing to consume other organisms, usually by using photosynthesis |

|

Green algae, Pyramimonas | Red and brown algae, diatoms and some dinoflagellates. Plant-like protists are important components of phytoplankton discussed below. | |||

| Animal-like | Heterotrophic protists that get their food consuming other organisms (bacteria, archaea and small algae) |

|

Radiolarian protist as drawn by Haeckel | Foraminiferans, and some marine amoebae, ciliates and flagellates. | |||

| Fungal-like | Saprotrophic protists that get their food from the remains of organisms that have broken down and decayed |

|

Marine slime nets form labyrinthine networks of tubes in which amoeba without pseudopods can travel | Marine lichen | |||

| Mixotrops | Various

|

Mixotrophic and osmotrophic protists that get their food from a combination of the above |

|

Euglena mutabilis, a photosynthetic flagellate | Many marine mixotrops are found among protists, particularly among ciliates and dinoflagellates[87] | ||

Protists are highly diverse organisms currently organised into 18 phyla, but are not easy to classify.[89][90] Studies have shown high protist diversity exists in oceans, deep sea-vents and river sediments, suggesting a large number of eukaryotic microbial communities have yet to be discovered.[91][92] There has been little research on mixotrophic protists, but recent studies in marine environments found mixotrophic protests contribute a significant part of the protist biomass.[87] Since protists are eukaryotes they possess within their cell at least one nucleus, as well as organelles such as mitochondria and Golgi bodies. Protists are asexual but can reproduce rapidly through mitosis or by fragmentation.

- Single-celled and microscopic protists

-

Fossil diatom frustule from 32 to 40 mya

-

Single-celled alga, Gephyrocapsa oceanica

-

Two dinoflagellates

-

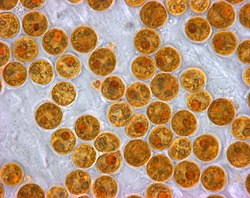

Zooxanthellae is a photosynthetic algae that lives inside hosts like coral

-

This ciliate is digesting cyanobacteria. The cytostome or mouth is at the bottom right.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

-

Ciliate ingesting a diatom

-

Amoeba engulfing a diatom

In contrast to the cells of prokaryotes, the cells of eukaryotes are highly organised. Plants, animals and fungi are usually multi-celled and are typically macroscopic. Most protists are single-celled and microscopic. But there are exceptions. Some single-celled marine protists are macroscopic. Some marine slime molds have unique life cycles that involve switching between unicellular, colonial, and multicellular forms.[95] Other marine protist are neither single-celled nor microscopic, such as seaweed.

- Macroscopic protists (see also unicellular macroalgae)

-

The single-celled giant amoeba has up to 1000 nuclei and reaches lengths of 5 mm

-

Gromia sphaerica is a large spherical testate amoeba which makes mud trails. Its diameter is up to 3.8 cm.[96]

-

Spiculosiphon oceana, a unicellular foraminiferan with an appearance and lifestyle that mimics a sponge, grows to 5 cm long.

-

The xenophyophore, another single-celled foraminiferan, lives in abyssal zones. It has a giant shell up to 20 cm across.[97]

-

Giant kelp, a brown algae, is not a true plant, yet it is multicellular and can grow to 50m

Protists have been described as a taxonomic grab bag of misfits where anything that doesn't fit into one of the main biological kingdoms can be placed.[98] Some modern authors prefer to exclude multicellular organisms from the traditional definition of a protist, restricting protists to unicellular organisms.[99][100] This more constrained definition excludes many brown, multicellular red and green algae, and slime molds.[101]

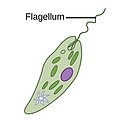

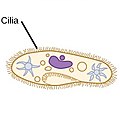

By locomotion

[edit]Another way of categorising protists is according to their mode of locomotion. Many unicellular protists, particularly protozoans, are motile and can generate movement using flagella, cilia or pseudopods. Cells which use flagella for movement are usually referred to as flagellates, cells which use cilia are usually referred to as ciliates, and cells which use pseudopods are usually referred to as amoeba or amoeboids. Other protists are not motile, and consequently have no movement mechanism.

Protists according to how they move

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of protist | Movement mechanism | Description | Example | Other examples | ||||

| Motile | Flagellates |

|

A flagellum (Latin for whip) is a lash-like appendage that protrudes from the cell body of some protists (as well as some bacteria). Flagellates use from one to several flagella for locomotion and sometimes as feeding and sensory organelle. |

|

Cryptophytes | All dinoflagellates and nanoflagellates (choanoflagellates, silicoflagellates, most green algae)[102][103] (Other protists go through a phase as gametes when they have temporary flagellum – some radiolarians, foraminiferans and Apicomplexa)

| ||

| Ciliates |

|

A cilium (Latin for eyelash) is a tiny flagellum. Ciliates use multiple cilia, which can number in many hundreds, to power themselves through the water. |

|

Paramecium bursaria click to see cilia |

Foraminiferans, and some marine amoebae, ciliates and flagellates. | |||

| Amoebas (amoeboids) |

|

Amoeba have the ability to alter shape by extending and retracting pseudopods (Greek for false feet).[104] |  |

Amoeba | Found in every major protist lineage. Amoeboid cells occur among the protozoans, but also in the algae and the fungi.[105][106] | |||

| Not motile | none

|

|

Diatom | Diatoms, coccolithophores, and non‐motile species of Phaeocystis[103] Among protozoans the parasitic Apicomplexa are non‐motile. | ||||

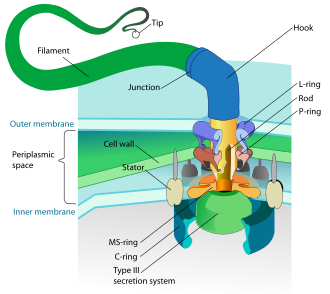

Flagellates include bacteria as well as protists. The rotary motor model used by bacteria uses the protons of an electrochemical gradient in order to move their flagella. Torque in the flagella of bacteria is created by particles that conduct protons around the base of the flagellum. The direction of rotation of the flagella in bacteria comes from the occupancy of the proton channels along the perimeter of the flagellar motor.[107]

Ciliates generally have hundreds to thousands of cilia that are densely packed together in arrays. During movement, an individual cilium deforms using a high-friction power stroke followed by a low-friction recovery stroke. Since there are multiple cilia packed together on an individual organism, they display collective behavior in a metachronal rhythm. This means the deformation of one cilium is in phase with the deformation of its neighbor, causing deformation waves that propagate along the surface of the organism. These propagating waves of cilia are what allow the organism to use the cilia in a coordinated manner to move. A typical example of a ciliated microorganism is the Paramecium, a one-celled, ciliated protozoan covered by thousands of cilia. The cilia beating together allow the Paramecium to propel through the water at speeds of 500 micrometers per second.[108]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Flagellate, ciliates and amoeba

-

Bacterial flagellum rotated by a molecular motor at its base

-

Salmon spermatozoa

-

The ciliate Oxytricha trifallax with cilia clearly visible

-

Amoeba with ingested diatoms

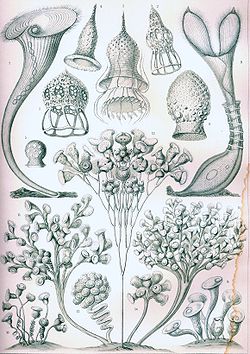

Marine fungi

[edit]

Over 1500 species of fungi are known from marine environments.[109] These are parasitic on marine algae or animals, or are saprobes feeding on dead organic matter from algae, corals, protozoan cysts, sea grasses, and other substrata.[110] Spores of many species have special appendages which facilitate attachment to the substratum.[111] Marine fungi can also be found in sea foam and around hydrothermal areas of the ocean.[112] A diverse range of unusual secondary metabolites is produced by marine fungi.[113]

Mycoplankton are saprotropic members of the plankton communities of marine and freshwater ecosystems.[114][115] They are composed of filamentous free-living fungi and yeasts associated with planktonic particles or phytoplankton.[116] Similar to bacterioplankton, these aquatic fungi play a significant role in heterotrophic mineralization and nutrient cycling.[117] While mostly microscopic, some mycoplankton can be up to 20 mm in diameter and over 50 mm in length.[118]

A typical milliliter of seawater contains about 103 to 104 fungal cells.[119] This number is greater in coastal ecosystems and estuaries due to nutritional runoff from terrestrial communities. A higher diversity of mycoplankton is found around coasts and in surface waters down to 1000 metres, with a vertical profile that depends on how abundant phytoplankton is.[120][121] This profile changes between seasons due to changes in nutrient availability.[122] Marine fungi survive in a constant oxygen deficient environment, and therefore depend on oxygen diffusion by turbulence and oxygen generated by photosynthetic organisms.[123]

Marine fungi can be classified as:[123]

- Lower fungi – adapted to marine habitats (zoosporic fungi, including mastigomycetes: oomycetes and chytridiomycetes)

- Higher fungi – filamentous, modified to planktonic lifestyle (hyphomycetes, ascomycetes, basidiomycetes). Most mycoplankton species are higher fungi.[120]

Lichens are mutualistic associations between a fungus, usually an ascomycete, and an alga or a cyanobacterium. Several lichens are found in marine environments.[124] Many more occur in the splash zone, where they occupy different vertical zones depending on how tolerant they are to submersion.[125] Some lichens live a long time; one species has been dated at 8,600 years.[126] However their lifespan is difficult to measure because what defines the same lichen is not precise.[127] Lichens grow by vegetatively breaking off a piece, which may or may not be defined as the same lichen, and two lichens of different ages can merge, raising the issue of whether it is the same lichen.[127]

The sea snail Littoraria irrorata damages plants of Spartina in the sea marshes where it lives, which enables spores of intertidal ascomycetous fungi to colonise the plant. The snail then eats the fungal growth in preference to the grass itself.[128]

According to fossil records, fungi date back to the late Proterozoic era 900-570 million years ago. Fossil marine lichens 600 million years old have been discovered in China.[129] It has been hypothesized that mycoplankton evolved from terrestrial fungi, likely in the Paleozoic era (390 million years ago).[130]

Marine microanimals

[edit]As juveniles, animals develop from microscopic stages, which can include spores, eggs and larvae. At least one microscopic animal group, the parasitic cnidarian Myxozoa, is unicellular in its adult form, and includes marine species. Other adult marine microanimals are multicellular. Microscopic adult arthropods are more commonly found inland in freshwater, but there are marine species as well. Microscopic adult marine crustaceans include some copepods, cladocera and tardigrades (water bears). Some marine nematodes and rotifers are also too small to be recognised with the naked eye, as are many loricifera, including the recently discovered anaerobic species that spend their lives in an anoxic environment.[131][132] Copepods contribute more to the secondary productivity and carbon sink of the world oceans than any other group of organisms.

- Marine microanimals

-

Over 10,000 marine species are copepods, small, often microscopic crustaceans

-

Darkfield photo of a gastrotrich, 0.06-3.0 mm long, a worm-like animal living between sediment particles

-

Armoured Pliciloricus enigmaticus, about 0.2 mm long, live in spaces between marine gravel

-

Rotifers, usually 0.1–0.5 mm long, may look like protists but are multicellular and belong to the Animalia

-

Tardigrades (water bears), about 0.5 mm long, are among the most resilient animals known

Primary producers

[edit]

Primary producers are the autotroph organisms that make their own food instead of eating other organisms. This means primary producers become the starting point in the food chain for heterotroph organisms that do eat other organisms. Some marine primary producers are specialised bacteria and archaea which are chemotrophs, making their own food by gathering around hydrothermal vents and cold seeps and using chemosynthesis. However most marine primary production comes from organisms which use photosynthesis on the carbon dioxide dissolved in the water. This process uses energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide[133]: 186–187 into sugars that can be used both as a source of chemical energy and of organic molecules that are used in the structural components of cells.[133]: 1242 Marine primary producers are important because they underpin almost all marine animal life by generating most of the oxygen and food that provide other organisms with the chemical energy they need to exist.

The principal marine primary producers are cyanobacteria, algae and marine plants. The oxygen released as a by-product of photosynthesis is needed by nearly all living things to carry out cellular respiration. In addition, primary producers are influential in the global carbon and water cycles. They stabilize coastal areas and can provide habitats for marine animals. The term division has been traditionally used instead of phylum when discussing primary producers, but the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants now accepts both terms as equivalents.[134]

Cyanobacteria

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

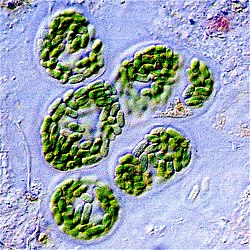

Cyanobacteria were the first organisms to evolve an ability to turn sunlight into chemical energy. They form a phylum (division) of bacteria which range from unicellular to filamentous and include colonial species. They are found almost everywhere on earth: in damp soil, in both freshwater and marine environments, and even on Antarctic rocks.[136] In particular, some species occur as drifting cells floating in the ocean, and as such were amongst the first of the phytoplankton.

The first primary producers that used photosynthesis were oceanic cyanobacteria about 2.3 billion years ago.[137][138] The release of molecular oxygen by cyanobacteria as a by-product of photosynthesis induced global changes in the Earth's environment. Because oxygen was toxic to most life on Earth at the time, this led to the near-extinction of oxygen-intolerant organisms, a dramatic change which redirected the evolution of the major animal and plant species.[139]

The tiny (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus, discovered in 1986, forms today an important part of the base of the ocean food chain and accounts for much of the photosynthesis of the open ocean[140] and an estimated 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.[141] It is possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater may contain 100,000 cells or more.[142]

Originally, biologists thought cyanobacteria was algae, and referred to it as "blue-green algae". The more recent view is that cyanobacteria are bacteria, and hence are not even in the same Kingdom as algae. Most authorities exclude all prokaryotes, and hence cyanobacteria from the definition of algae.[143][144]

Algae

[edit]Algae is an informal term for a widespread and diverse group of photosynthetic protists which are not necessarily closely related and are thus polyphyletic. Marine algae can be divided into six groups: green, red and brown algae, euglenophytes, dinoflagellates and diatoms.

Dinoflagellates and diatoms are important components of marine algae and have their own sections below. Euglenophytes are a phylum of unicellular flagellates with only a few marine members.

Not all algae are microscopic. Green, red and brown algae all have multicellular macroscopic forms that make up the familiar seaweeds. Green algae, an informal group, contains about 8,000 recognised species.[145] Many species live most of their lives as single cells or are filamentous, while others form colonies made up from long chains of cells, or are highly differentiated macroscopic seaweeds. Red algae, a (disputed) phylum contains about 7,000 recognised species,[146] mostly multicellular and including many notable seaweeds.[146][147] Brown algae form a class containing about 2,000 recognised species,[148] mostly multicellular and including many seaweeds such as kelp. Unlike higher plants, algae lack roots, stems, or leaves. They can be classified by size as microalgae or macroalgae.

Microalgae are the microscopic types of algae, not visible to the naked eye. They are mostly unicellular species which exist as individuals or in chains or groups, though some are multicellular. Microalgae are important components of the marine protists discussed above, as well as the phytoplankton discussed below. They are very diverse. It has been estimated there are 200,000-800,000 species of which about 50,000 species have been described.[149] Depending on the species, their sizes range from a few micrometers (μm) to a few hundred micrometers. They are specially adapted to an environment dominated by viscous forces.

Unicellular organisms are usually microscopic. There are exceptions. Mermaid's wineglass, a genus of subtropical green algae, is single-celled but remarkably large and complex in form with a single large nucleus, making it a model organism for studying cell biology.[150] Another single-celled algae, Caulerpa taxifolia, has the appearance of a vascular plant including "leaves" arranged neatly up stalks like a fern. Selective breeding in aquariums to produce hardier strains resulted in an accidental release into the Mediterranean where it has become an invasive species known colloquially as killer algae.[151]

-

Chlamydomonas globosa, a unicellular green alga with two flagella just visible at bottom left

-

Centric diatom

-

Dinoflagellates

-

Colonial algal chains

Macroalgae are the larger, multicellular and more visible types of algae, commonly called seaweeds. Seaweeds usually grow in shallow coastal waters where they are anchored to the seafloor by a holdfast. Like microalgae, macroalgae (seaweeds) can be regarded as marine protists since they are not true plants. But they are not microorganisms, so they are not within the scope of this article.

Marine microplankton

[edit]

Plankton (from Greek for wanderers) are a diverse group of organisms that live in the water column of large bodies of water but cannot swim against a current. As a result, they wander or drift with the currents.[153] Plankton are defined by their ecological niche, not by any phylogenetic or taxonomic classification. They are a crucial source of food for many marine animals, from forage fish to whales. Plankton can be divided into a plant-like component and an animal component.

Phytoplankton

[edit]

Phytoplankton are the plant-like components of the plankton community ("phyto" comes from the Greek for plant). They are autotrophic (self-feeding), meaning they generate their own food and do not need to consume other organisms.

Phytoplankton perform three crucial functions: they generate nearly half of the world atmospheric oxygen, they regulate ocean and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, and they form the base of the marine food web. When conditions are right, blooms of phytoplankton algae can occur in surface waters. Phytoplankton are r-strategists which grow rapidly and can double their population every day. The blooms can become toxic and deplete the water of oxygen. However, phytoplankton numbers are usually kept in check by the phytoplankton exhausting available nutrients and by grazing zooplankton.[156]

Phytoplankton consist mainly of microscopic photosynthetic eukaryotes which inhabit the upper sunlit layer in all oceans. They need sunlight so they can photosynthesize. Most phytoplankton are single-celled algae, but other phytoplankton are bacteria and some are protists.[157] Phytoplankton include cyanobacteria (above), diatoms, various other types of algae (red, green, brown, and yellow-green), dinoflagellates, euglenoids, coccolithophorids, cryptomonads, chlorophytes, prasinophytes, and silicoflagellates. They form the base of the primary production that drives the ocean food web, and account for half of the current global primary production, more than the terrestrial forests.[158]

- Phytoplankton

-

Phytoplankton are the foundation of the ocean food chain

-

They come in many shapes and sizes.

-

Colonial phytoplankton

-

The cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus accounts for much of the ocean's primary production

-

Green cyanobacteria scum washed up on a rock in California

Diatoms

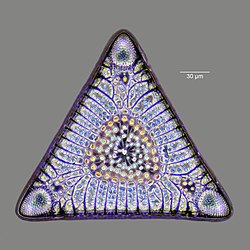

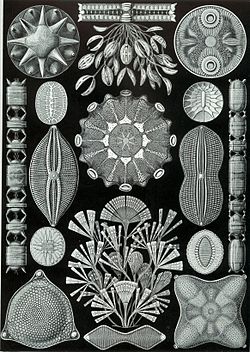

[edit]Diatoms form a (disputed) phylum containing about 100,000 recognised species of mainly unicellular algae. Diatoms generate about 20 per cent of the oxygen produced on the planet each year,[93] take in over 6.7 billion metric tons of silicon each year from the waters in which they live,[159] and contribute nearly half of the organic material found in the oceans.

-

Diatoms are one of the most common types of phytoplankton

-

Their protective shells (frustles) are made of silicon

-

They come in many shapes and sizes

Diatoms are enclosed in protective silica (glass) shells called frustules. Each frustule is made from two interlocking parts covered with tiny holes through which the diatom exchanges nutrients and wastes.[156] The frustules of dead diatoms drift to the ocean floor where, over millions of years, they can build up as much as half a mile deep.[160]

-

Silicified frustule of a pennate diatom with two overlapping halves

-

Guinardia delicatula, a diatom responsible for algal blooms in the North Sea and the English Channel[161]

-

Fossil diatom

-

There are over 100,000 species of diatoms which account for 50% of the ocean's primary production

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Coccolithophores

[edit]Coccolithophores are minute unicellular photosynthetic protists with two flagella for locomotion. Most of them are protected by a shell covered with ornate circular plates or scales called coccoliths. The coccoliths are made from calcium carbonate. The calcite shells are important to the marine carbon cycle.[163] The term coccolithophore derives from the Greek for a seed carrying stone, referring to their small size and the coccolith stones they carry. Under the right conditions they bloom, like other phytoplankton, and can turn the ocean milky white.[164]

-

Coccolithophores have plates called coccoliths

-

Coccolithus pelagicus ssp. braarudii

-

Algae bloom of Emiliania huxleyi off the southern coast of England

-

Extinct fossil

Microbial rhodopsin

[edit]

(2) it changes its configuration so a proton is expelled from the cell

(3) the chemical potential causes the proton to flow back to the cell

(4) thus generating energy

(5) in the form of adenosine triphosphate.[165]

Phototrophic metabolism relies on one of three energy-converting pigments: chlorophyll, bacteriochlorophyll, and retinal. Retinal is the chromophore found in rhodopsins. The significance of chlorophyll in converting light energy has been written about for decades, but phototrophy based on retinal pigments is just beginning to be studied.[166]

In 2000 a team of microbiologists led by Edward DeLong made a crucial discovery in the understanding of the marine carbon and energy cycles. They discovered a gene in several species of bacteria[168][169] responsible for production of the protein rhodopsin, previously unheard of in bacteria. These proteins found in the cell membranes are capable of converting light energy to biochemical energy due to a change in configuration of the rhodopsin molecule as sunlight strikes it, causing the pumping of a proton from inside out and a subsequent inflow that generates the energy.[170] The archaeal-like rhodopsins have subsequently been found among different taxa, protists as well as in bacteria and archaea, though they are rare in complex multicellular organisms.[171][172][173]

Research in 2019 shows these "sun-snatching bacteria" are more widespread than previously thought and could change how oceans are affected by global warming. "The findings break from the traditional interpretation of marine ecology found in textbooks, which states that nearly all sunlight in the ocean is captured by chlorophyll in algae. Instead, rhodopsin-equipped bacteria function like hybrid cars, powered by organic matter when available — as most bacteria are — and by sunlight when nutrients are scarce."[174][166]

There is an astrobiological conjecture called the Purple Earth hypothesis which surmises that original life forms on Earth were retinal-based rather than chlorophyll-based, which would have made the Earth appear purple instead of green.[175][176]

Redfield and f- ratios

[edit]During the 1930s Alfred C. Redfield found similarities between the composition of elements in phytoplankton and the major dissolved nutrients in the deep ocean.[177] Redfield proposed that the ratio of carbon to nitrogen to phosphorus (106:16:1) in the ocean was controlled by the phytoplankton's requirements, as phytoplankton subsequently release nitrogen and phosphorus as they remineralize. This ratio has become known as the Redfield ratio, and is used as a fundamental principle in describing the stoichiometry of seawater and phytoplankton evolution.[178]

However, the Redfield ratio is not a universal value and can change with things like geographical latitude.[179] Based on allocation of resources, phytoplankton can be classified into three different growth strategies: survivalist, bloomer and generalist. Survivalist phytoplankton has a high N:P ratio (>30) and contains an abundance of resource-acquisition machinery to sustain growth under scarce resources. Bloomer phytoplankton has a low N:P ratio (<10), contains a high proportion of growth machinery and is adapted to exponential growth. Generalist phytoplankton has similar N:P to the Redfield ratio and contain relatively equal resource-acquisition and growth machinery.[178]

The f-ratio is the fraction of total primary production fuelled by nitrate (as opposed to that fuelled by other nitrogen compounds such as ammonium). The ratio was originally defined by Richard Eppley and Bruce Peterson in one of the first papers estimating global oceanic production.[180]

Zooplankton

[edit]Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek for animal). They are heterotrophic (other-feeding), meaning they cannot produce their own food and must consume instead other plants or animals as food. In particular, this means they eat phytoplankton.

Zooplankton are generally larger than phytoplankton, mostly still microscopic but some can be seen with the naked eye. Many protozoans (single-celled protists that prey on other microscopic life) are zooplankton, including zooflagellates, foraminiferans, radiolarians, some dinoflagellates and marine microanimals. Macroscopic zooplankton (not generally covered in this article) include pelagic cnidarians, ctenophores, molluscs, arthropods and tunicates, as well as planktonic arrow worms and bristle worms.

Microzooplankton: major grazers of the plankton...

Many species of protozoa (eukaryotes) and bacteria (prokaryotes) prey on other microorganisms; the feeding mode is evidently ancient, and evolved many times in both groups.[181][182][183] Among freshwater and marine zooplankton, whether single-celled or multi-cellular, predatory grazing on phytoplankton and smaller zooplankton is common, and found in many species of nanoflagellates, dinoflagellates, ciliates, rotifers, a diverse range of meroplankton animal larvae, and two groups of crustaceans, namely copepods and cladocerans.[184]

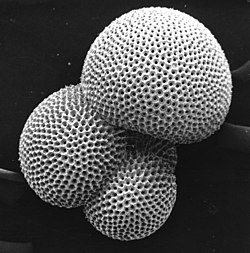

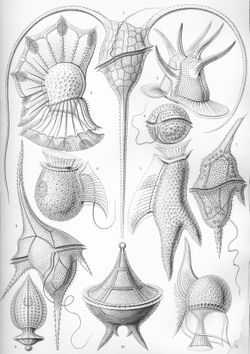

Radiolarians

[edit]Radiolarians are unicellular predatory protists encased in elaborate globular shells usually made of silica and pierced with holes. Their name comes from the Latin for "radius". They catch prey by extending parts of their body through the holes. As with the silica frustules of diatoms, radiolarian shells can sink to the ocean floor when radiolarians die and become preserved as part of the ocean sediment. These remains, as microfossils, provide valuable information about past oceanic conditions.[185]

-

Like diatoms, radiolarians come in many shapes

-

Also like diatoms, radiolarian shells are usually made of silicate

-

However acantharian radiolarians have shells made from strontium sulfate crystals

-

Cutaway schematic diagram of a spherical radiolarian shell

-

Cladococcus abietinus

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Foraminiferans

[edit]Like radiolarians, foraminiferans (forams for short) are single-celled predatory protists, also protected with shells that have holes in them. Their name comes from the Latin for "hole bearers". Their shells, often called tests, are chambered (forams add more chambers as they grow). The shells are usually made of calcite, but are sometimes made of agglutinated sediment particles or chiton, and (rarely) of silica. Most forams are benthic, but about 40 species are planktic.[187] They are widely researched with well established fossil records which allow scientists to infer a lot about past environments and climates.[185]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

-

section showing chambers of a spiral foram

-

Live Ammonia tepida streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food

-

Group of planktonic forams

-

Fossil nummulitid forams of various sizes from the Eocene

A number of forams are mixotrophic (see below). These have unicellular algae as endosymbionts, from diverse lineages such as the green algae, red algae, golden algae, diatoms, and dinoflagellates.[187] Mixotrophic foraminifers are particularly common in nutrient-poor oceanic waters.[189] Some forams are kleptoplastic, retaining chloroplasts from ingested algae to conduct photosynthesis.[190]

Amoeba

[edit]Amoeba can be shelled (testate) or naked.

- Shelled and naked amoeba

-

Testate amoeba, Cyphoderia sp.

-

Shell or test of a testate amoeba, Arcella sp.

-

Xenogenic testate amoeba covered in diatoms (from Penard's Amoeba Collection)

-

Naked amoeba, Chaos sp.

-

Naked amoeba showing food vacuoles and ingested diatom

Ciliates

[edit]-

Holophyra ovum

-

Mesodinium rubrum produce deep red blooms using enslaved chloroplasts from their algal prey [191]

-

Several taxa of ciliates interacting

-

Blepharisma americanum swimming in a drop of pond water with other microorganisms

Mixotrophs

[edit]A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comprise more than half of all microscopic plankton.[192] There are two types of eukaryotic mixotrophs: those with their own chloroplasts, and those with endosymbionts—and others that acquire them through kleptoplasty or by enslaving the entire phototrophic cell.[193]

The distinction between plants and animals often breaks down in very small organisms. Possible combinations are photo- and chemotrophy, litho- and organotrophy, auto- and heterotrophy or other combinations of these. Mixotrophs can be either eukaryotic or prokaryotic.[194] They can take advantage of different environmental conditions.[195]

Recent studies of marine microzooplankton found 30–45% of the ciliate abundance was mixotrophic, and up to 65% of the amoeboid, foram and radiolarian biomass was mixotrophic.[87]

Phaeocystis is an important algal genus found as part of the marine phytoplankton around the world. It has a polymorphic life cycle, ranging from free-living cells to large colonies.[196] It has the ability to form floating colonies, where hundreds of cells are embedded in a gel matrix, which can increase massively in size during blooms.[197] As a result, Phaeocystis is an important contributor to the marine carbon[198] and sulfur cycles.[199] Phaeocystis species are endosymbionts to acantharian radiolarians.[200][201]

Mixotrophic plankton that combine phototrophy and heterotrophy – table based on Stoecker et al., 2017[202]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General types | Description | Example | Further examples | ||||

| Bacterioplankton | Photoheterotrophic bacterioplankton |

|

Vibrio cholerae | Roseobacter spp. Erythrobacter spp. Gammaproteobacterial clade OM60 Widespread among bacteria and archaea | |||

| Phytoplankton | Called constitutive mixotrophs by Mitra et al., 2016.[203] Phytoplankton that eat: photosynthetic protists with inherited plastids and the capacity to ingest prey. |

|

Ochromonas species | Ochromonas spp. Prymnesium parvum Dinoflagellate examples: Fragilidium subglobosum,Heterocapsa triquetra,Karlodinium veneficum,Neoceratium furca,Prorocentrum minimum | |||

| Zooplankton | Called nonconstitutive mixotrophs by Mitra et al., 2016.[203] Zooplankton that are photosynthetic: microzooplankton or metazoan zooplankton that acquire phototrophy through chloroplast retentiona or maintenance of algal endosymbionts. | ||||||

| Generalists | Protists that retain chloroplasts and rarely other organelles from many algal taxa |

|

Most oligotrich ciliates that retain plastidsa | ||||

| Specialists | 1. Protists that retain chloroplasts and sometimes other organelles from one algal species or very closely related algal species |

|

Dinophysis acuminata | Dinophysis spp. Myrionecta rubra | |||

| 2. Protists or zooplankton with algal endosymbionts of only one algal species or very closely related algal species |

|

Noctiluca scintillans | Metazooplankton with algal endosymbionts Most mixotrophic Rhizaria (Acantharea, Polycystinea, and Foraminifera) Green Noctiluca scintillans | ||||

| aChloroplast (or plastid) retention = sequestration = enslavement. Some plastid-retaining species also retain other organelles and prey cytoplasm. | |||||||

- Mixoplankton

-

Tintinnid ciliate Favella

-

Euglena mutabilis, a photosynthetic flagellate

-

Zoochlorellae (green) living inside the ciliate Stichotricha secunda

Dinoflagellates

[edit]Dinoflagellates are part of the algae group, and form a phylum of unicellular flagellates with about 2,000 marine species.[204] The name comes from the Greek "dinos" meaning whirling and the Latin "flagellum" meaning a whip or lash. This refers to the two whip-like attachments (flagella) used for forward movement. Most dinoflagellates are protected with red-brown, cellulose armour. Like other phytoplankton, dinoflagellates are r-strategists which under right conditions can bloom and create red tides. Excavates may be the most basal flagellate lineage.[102]

By trophic orientation dinoflagellates cannot be uniformly categorized. Some dinoflagellates are known to be photosynthetic, but a large fraction of these are in fact mixotrophic, combining photosynthesis with ingestion of prey (phagotrophy).[205] Some species are endosymbionts of marine animals and other protists, and play an important part in the biology of coral reefs. Others predate other protozoa, and a few forms are parasitic. Many dinoflagellates are mixotrophic and could also be classified as phytoplankton.

The toxic dinoflagellate Dinophysis acuta acquire chloroplasts from its prey. "It cannot catch the cryptophytes by itself, and instead relies on ingesting ciliates such as the red Myrionecta rubra, which sequester their chloroplasts from a specific cryptophyte clade (Geminigera/Plagioselmis/Teleaulax)".[202]

-

Gyrodinium, one of the few naked dinoflagellates which lack armour

-

The dinoflagellate Protoperidinium extrudes a large feeding veil to capture prey

-

Nassellarian radiolarians can be in symbiosis with dinoflagellates

-

The dinoflagellate Dinophysis acuta

Dinoflagellates often live in symbiosis with other organisms. Many nassellarian radiolarians house dinoflagellate symbionts within their tests.[207] The nassellarian provides ammonium and carbon dioxide for the dinoflagellate, while the dinoflagellate provides the nassellarian with a mucous membrane useful for hunting and protection against harmful invaders.[208] There is evidence from DNA analysis that dinoflagellate symbiosis with radiolarians evolved independently from other dinoflagellate symbioses, such as with foraminifera.[209]

Some dinoflagellates are bioluminescent. At night, ocean water can light up internally and sparkle with blue light because of these dinoflagellates.[210][211] Bioluminescent dinoflagellates possess scintillons, individual cytoplasmic bodies which contain dinoflagellate luciferase, the main enzyme involved in the luminescence. The luminescence, sometimes called the phosphorescence of the sea, occurs as brief (0.1 sec) blue flashes or sparks when individual scintillons are stimulated, usually by mechanical disturbances from, for example, a boat or a swimmer or surf.[212]

-

Tripos muelleri is recognisable by its U-shaped horns

-

Karenia brevis produces red tides highly toxic to humans[214]

-

Noctiluca scintillans, a bioluminescent dinoflagellate[215]

Marine sediments and microfossils

[edit]

Sediments at the bottom of the ocean have two main origins, terrigenous and biogenous.

Terrigenous sediments account for about 45% of the total marine sediment, and originate in the erosion of rocks on land, transported by rivers and land runoff, windborne dust, volcanoes, or grinding by glaciers.

Biogenous sediments account for the other 55% of the total sediment, and originate in the skeletal remains of marine protists (single-celled plankton and benthos microorganisms). Much smaller amounts of precipitated minerals and meteoric dust can also be present. Ooze, in the context of a marine sediment, does not refer to the consistency of the sediment but to its biological origin. The term ooze was originally used by John Murray, the "father of modern oceanography", who proposed the term radiolarian ooze for the silica deposits of radiolarian shells brought to the surface during the Challenger expedition.[217] A biogenic ooze is a pelagic sediment containing at least 30 per cent from the skeletal remains of marine organisms.

Main types of biogenic ooze

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| type | mineral forms |

protist involved |

name of skeleton | typical size (mm) |

||||

| Siliceous ooze | SiO2 silica quartz glass opal chert |

diatom |

|

frustule | 0.002 to 0.2[218] |

|

diatom microfossil from 40 million years ago | |

| radiolarian |

|

test or shell | 0.1 to 0.2 |

|

elaborate silica shell of a radiolarian | |||

| Calcareous ooze | CaCO3 calcite aragonite limestone marble chalk |

foraminiferan |

|

test or shell | < 1 |

|

Calcified test of a planktic foraminiferan. There are about 10,000 living species of foraminiferans[219] | |

| coccolithophore |

|

coccoliths | < 0.1[220] |

|

Coccolithophores are the largest global source of biogenic calcium carbonate, and significantly contribute to the global carbon cycle.[221] They are the main constituent of chalk deposits such as the white cliffs of Dover. | |||

-

Diatomaceous earth is a soft, siliceous, sedimentary rock made up of microfossils in the form of the frustules (shells) of single cell diatoms (click to magnify)

-

Calcareous microfossils from marine sediment consisting mainly of star-shaped discoaster with a sprinkling of coccoliths

-

Shells (tests), usually made of calcium carbonate, from a foraminiferal ooze on the deep ocean floor

-

Illustration of a Globigerina ooze

-

Marble can contain protist microfossils of foraminiferans, coccolithophores, calcareous nannoplankton and algae, ostracodes, pteropods, calpionellids and bryozoa[222]

-

Opal can contain protist microfossils of diatoms, radiolarians, silicoflagellates and ebridians[222]

-

Distribution of sediment types on the seafloor

Within each colored area, the type of material shown is what dominates, although other materials are also likely to be present.

For further information, see here

Marine microbenthos

[edit]

Marine microbenthos are microorganisms that live in the benthic zone of the ocean – that live near or on the seafloor, or within or on surface seafloor sediments. The word benthos comes from Greek, meaning "depth of the sea". Microbenthos are found everywhere on or about the seafloor of continental shelves, as well as in deeper waters, with greater diversity in or on seafloor sediments. In shallow waters, seagrass meadows, coral reefs and kelp forests provide particularly rich habitats. In photic zones benthic diatoms dominate as photosynthetic organisms. In intertidal zones changing tides strongly control opportunities for microbenthos.

-

Elphidium a widespread abundant genus of benthic forams

-

Heterohelix, an extinct genus of benthic forams

Both foraminifera and diatoms have planktonic and benthic forms, that is, they can drift in the water column or live on sediment at the bottom of the ocean. Either way, their shells end up on the seafloor after they die. These shells are widely used as climate proxies. The chemical composition of the shells are a consequence of the chemical composition of the ocean at the time the shells were formed. Past water temperatures can be also be inferred from the ratios of stable oxygen isotopes in the shells, since lighter isotopes evaporate more readily in warmer water leaving the heavier isotopes in the shells. Information about past climates can be inferred further from the abundance of forams and diatoms, since they tend to be more abundant in warm water.[223]

The sudden extinction event which killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago also rendered extinct three-quarters of all other animal and plant species. However, deep-sea benthic forams flourished in the aftermath. In 2020 it was reported that researchers have examined the chemical composition of thousands of samples of these benthic forams and used their findings to build the most detailed climate record of Earth ever.[224][225]

Some endoliths have extremely long lives. In 2013 researchers reported evidence of endoliths in the ocean floor, perhaps millions of years old, with a generation time of 10,000 years.[226] These are slowly metabolizing and not in a dormant state. Some Actinomycetota found in Siberia are estimated to be half a million years old.[227][228][229]

Marine microbiomes

[edit]Symbiosis and holobionts

[edit]

The concept of the holobiont was initially defined by Dr. Lynn Margulis in her 1991 book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation as an assemblage of a host and the many other species living in or around it, which together form a discrete ecological unit.[231] The components of a holobiont are individual species or bionts, while the combined genome of all bionts is the hologenome.[232]

The concept has subsequently evolved since this original definition,[233] with the focus moving to the microbial species associated with the host. Thus the holobiont includes the host, virome, microbiome, and other members, all of which contribute in some way to the function of the whole.[234][235] A holobiont typically includes a eukaryote host and all of the symbiotic viruses, bacteria, fungi, etc. that live on or inside it.[236]

However, there is controversy over whether holobionts can be viewed as single evolutionary units.[237]

Reef-building corals are well-studied holobionts that include the coral itself (a eukaryotic invertebrate within class Anthozoa), photosynthetic dinoflagellates called zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium), and associated bacteria and viruses.[238] Co-evolutionary patterns exist for coral microbial communities and coral phylogeny.[239]

Marine food web

[edit]

Marine microorganisms play central roles in the marine food web.

The viral shunt pathway is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms.[244] Viral shunting helps maintain diversity within the microbial ecosystem by preventing a single species of marine microbe from dominating the micro-environment.[245] The DOM recycled by the viral shunt pathway is comparable to the amount generated by the other main sources of marine DOM.[246]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

-

Pelagibacter ubique, the most abundant bacteria in the ocean, plays a major role in the global carbon cycle.

-

Marine snow is the shower of organic particles that falls from upper waters to the deep ocean[248] It is a major exporter of carbon.

Niche communities

[edit]Sea ice microbial communities (SIMCO) refer to groups of microorganisms living within and at the interfaces of sea ice at the poles. The ice matrix they inhabit has strong vertical gradients of salinity, light, temperature and nutrients. Sea ice chemistry is most influenced by the salinity of the brine which affects the pH and the concentration of dissolved nutrients and gases. The brine formed during the melting sea ice creates pores and channels in the sea ice in which these microbes can live. As a result of these gradients and dynamic conditions, a higher abundance of microbes are found in the lower layer of the ice, although some are found in the middle and upper layers.[251]

Hydrothermal vents are located where the tectonic plates are moving apart and spreading. This allows water from the ocean to enter into the crust of the earth where it is heated by the magma. The increasing pressure and temperature forces the water back out of these openings, on the way out, the water accumulates dissolved minerals and chemicals from the rocks that it encounters. Vents can be characterized by temperature and chemical composition as diffuse vents which release clear relatively cool water usually below 30 °C, as white smokers which emit milky coloured water at warmer temperatures, about 200-330 °C, and as black smokers which emit water darkened by accumulated precipitates of sulfide at hot temperatures, about 300-400 °C.[252]

Hydrothermal vent microbial communities are microscopic unicellular organisms that live and reproduce in the chemically distinct area around hydrothermal vents. These include organisms in microbial mats, free floating cells, and bacteria in endosymbiotic relationships with animals. Because there is no sunlight at these depths, energy is provided by chemosynthesis where symbiotic bacteria and archaea form the bottom of the food chain and are able to support a variety of organisms such as giant tube worms and Pompeii worms. These organisms utilize this symbiotic relationship in order to utilize and obtain the chemical energy that is released at these hydrothermal vent areas.[253] Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria can derive nutrients and energy from the geological activity at a hydrothermal vent to fix carbon into organic forms.[254]

Viruses are also a part of the hydrothermal vent microbial community and their influence on the microbial ecology in these ecosystems is a burgeoning field of research.[255] Viruses are the most abundant life in the ocean, harboring the greatest reservoir of genetic diversity.[256] As their infections are often fatal, they constitute a significant source of mortality and thus have widespread influence on biological oceanographic processes, evolution and biogeochemical cycling within the ocean.[257] Evidence has been found however to indicate that viruses found in vent habitats have adopted a more mutualistic than parasitic evolutionary strategy in order to survive the extreme and volatile environment they exist in.[258] Deep-sea hydrothermal vents were found to have high numbers of viruses indicating high viral production.[259] Like in other marine environments, deep-sea hydrothermal viruses affect abundance and diversity of prokaryotes and therefore impact microbial biogeochemical cycling by lysing their hosts to replicate.[260] However, in contrast to their role as a source of mortality and population control, viruses have also been postulated to enhance survival of prokaryotes in extreme environments, acting as reservoirs of genetic information. The interactions of the virosphere with microorganisms under environmental stresses is therefore thought to aide microorganism survival through dispersal of host genes through horizontal gene transfer.[261]

Deep biosphere and dark matter

[edit]

The deep biosphere is that part of the biosphere that resides below the first few meters of the surface. It extends at least 5 kilometers below the continental surface and 10.5 kilometers below the sea surface, with temperatures that may exceed 100 °C.

Above the surface living organisms consume organic matter and oxygen. Lower down, these are not available, so they make use of "edibles" (electron donors) such as hydrogen released from rocks by various chemical processes, methane, reduced sulfur compounds and ammonium. They "breathe" electron acceptors such as nitrates and nitrites, manganese and iron oxides, oxidized sulfur compounds and carbon dioxide.

There is very little energy at greater depths, and metabolism can be up to a million times slower than at the surface. Cells may live for thousands of years before dividing and there is no known limit to their age. The subsurface accounts for about 90% of the biomass in bacteria and archaea, and 15% of the total biomass for the biosphere. Eukaryotes are also found, mostly microscopic, but including some multicellular life. Viruses are also present and infect the microbes.

In 2018, researchers from the Deep Carbon Observatory announced that life forms, including 70% of the bacteria and archaea on Earth, totaling a biomass of 23 billion tonnes carbon, live up to 4.8 km (3.0 mi) deep underground, including 2.5 km (1.6 mi) below the seabed.[262][263][264] In 2019 microbial organisms were discovered living 7,900 feet (2,400 m) below the surface, breathing sulfur and eating rocks such as pyrite as their regular food source.[265][266][267] This discovery occurred in the oldest known water on Earth.[268]

In 2020 researchers reported they had found what could be the longest-living life forms ever: aerobic microorganisms which had been in quasi-suspended animation for up to 101.5 million years. The microorganisms were found in organically poor sediments 68.9 metres (226 feet) below the seafloor in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG), "the deadest spot in the ocean".[269][270]

To date biologists have been unable to culture in the laboratory the vast majority of microorganisms. This applies particularly to bacteria and archaea, and is due to a lack of knowledge or ability to supply the required growth conditions.[271][272] The term microbial dark matter has come to be used to describe microorganisms scientists know are there but have been unable to culture, and whose properties therefore remain elusive.[271] Microbial dark matter is unrelated to the dark matter of physics and cosmology, but is so-called for the difficulty in effectively studying it. It is hard to estimate its relative magnitude, but the accepted gross estimate is that less than one per cent of microbial species in a given ecological niche is culturable. In recent years effort is being put to decipher more of the microbial dark matter by means of learning their genome DNA sequence from environmental samples[273] and then by gaining insights to their metabolism from their sequenced genome, promoting the knowledge required for their cultivation.

Microbial diversity

[edit]-

Estimates of microbial species counts in the three domains of lifeBacteria are the oldest and most biodiverse group, followed by Archaea and Fungi (the most recent groups). In 1998, before awareness of the extent of microbial life had gotten underway, Robert M. May[274] estimated there were 3 million species of living organisms on the planet. But in 2016, Locey and Lennon[275] estimated the number of microorganism species could be as high as 1 trillion.[276]

-

Microbial diversityComparative representation of the known and estimated (small box) and the yet unknown (large box) microbial diversity, which applies to both marine and terrestrial microorganisms. The text boxes refer to factors that adversely affect the knowledge of the microbial diversity that exists on the planet.[276]

Sampling techniques

[edit]

The blue background indicates the filtered volume required to obtain sufficient organism numbers for analysis.

Actual volumes from which organisms are sampled are always recorded.[277]

Identifying microorganisms

[edit]using modern imaging techniques.[277]

Traditionally, the phylogeny of microorganisms was inferred and their taxonomy was established based on studies of morphology. However, developments in molecular phylogenetics have allowed evolutionary relationship of species to be established by analyzing deeper characteristics, such as their DNA and protein sequences, for example ribosomal DNA.[278] The lack of easily accessible morphological features, such as those present in animals and plants, particularly hampered early efforts at classifying bacteria and archaea. This resulted in erroneous, distorted and confused classification, an example of which, noted Carl Woese, is Pseudomonas whose etymology ironically matched its taxonomy, namely "false unit".[279] Many bacterial taxa have been reclassified or redefined using molecular phylogenetics.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Methods of identifying microorganisms[282]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogenic media |

Microscopy techniques |

Biochemical techniques |

Molecular techniques |

Traditional media

|

Bright field Dark field SEM TEM CLSM ATM Inverted microscopy |

Spectrometry – FTIR – Raman spectrometry Mass spectrometry – GC – LC – MALDI-TOF – ESI Electrokinetic separation Microfluidic chip Propriety methods – Wickerham card – API – BBL Crystal – Vitek – Biolog |

PCR Real-time qPCR Rapid PCR PCR sequencing RFLP PFGE Ribotyping WGS MALDI-TOF MS |

Recent developments in molecular sequencing have allowed for the recovery of genomes in situ, directly from environmental samples and avoiding the need for culturing. This has led for example, to a rapid expansion in knowledge of the diversity of bacterial phyla. These techniques are genome-resolved metagenomics and single-cell genomics.

The new sequencing technologies and the accumulation of sequence data have resulted in a paradigm shift, highlighted both the ubiquity of microbial communities in association within higher organisms and the critical roles of microbes in ecosystem health.[283] These new possibilities have revolutionized microbial ecology, because the analysis of genomes and metagenomes in a high-throughput manner provides efficient methods for addressing the functional potential of individual microorganisms as well as of whole communities in their natural habitats.[284][285][286]

Using omics data

[edit]

Omics is a term used informally to refer to branches of biology whose names end in the suffix -omics, such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and glycomics. Marine Omics has recently emerged as a field of research of its own.[288] Omics aims at collectively characterising and quantifying pools of biological molecules that translate into the structure, function, and dynamics of an organism or organisms. For example, functional genomics aims at identifying the functions of as many genes as possible of a given organism. It combines different -omics techniques such as transcriptomics and proteomics with saturated mutant collections.[289][290]