Mariupol

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 49 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 49 min

Mariupol

Маріуполь (Ukrainian) | |

|---|---|

City | |

From top to bottom and left to right:

| |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 47°5′45″N 37°32′58″E / 47.09583°N 37.54944°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Donetsk Oblast |

| Raion | Mariupol Raion |

| Hromada | Mariupol urban hromada |

| Founded | 1778 |

| Urban districts | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vadym Boychenko (de jure)[2] Oleg Morgun (de facto)[3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 244 km2 (94 sq mi) |

| Population (2023) | |

• Total | 120,000 (per Ukraine) |

| (May 2023, after 2022 Russian siege and attacks)[4] before this, the January 2022 estimate was 425,681[5] | |

| Postal code | 87500—87590 |

| Area code | +380 629 |

| Climate | Hot summer subtype |

| Website | mariupolrada |

| |

| City government website maintained in exile | |

Mariupol[a] is a city in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the northern coast (Pryazovia) of the Sea of Azov, at the mouth of the Kalmius River. Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was the tenth-largest city in the country and the second-largest city in Donetsk Oblast, with an estimated population of 425,681 people in January 2022;[5] as of August 2023, Ukrainian authorities estimate the population of Mariupol at approximately 120,000.[4] Mariupol has been occupied by Russian forces since May 2022.

Historically, the city of Mariupol was a centre for trade and manufacturing, and played a key role in the development of higher education and many businesses and also served as a coastal resort on the Sea of Azov. In 1948, Mariupol was renamed Zhdanov (Russian: Жданов) after Andrei Zhdanov, a native of the city who had become a high-ranking official of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and a close ally to Joseph Stalin. The name was part of a larger effort to rename cities after high-ranking political figures in the Soviet Union. The historic name was restored in 1989.[6]

Mariupol was founded on the site of a former encampment for Cossacks, known as Kalmius,[7] and was granted city rights within the Russian Empire in 1778. It played a key role in Stalin-era industrialization; it was a centre for grain trade, metallurgy, and heavy engineering – including the Illich Iron and Steel Works and the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works.

Beginning on 24 February 2022, a three-month-long siege by Russian forces largely destroyed the city, for which it was named a "Hero City of Ukraine" by the Ukrainian government.[8] On 16 May 2022, the last Ukrainian troops who remained in Mariupol surrendered at the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works, and the Russian military secured complete control over the city by 20 May.[9]

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]Neolithic burial grounds excavated on the shore of the Sea of Azov[10] date from the end of the third millennium BCE. Over 120 skeletons have been discovered, with stone and bone instruments, beads, shell-work, and animal teeth.[10]

Crimean Khanate

[edit]

From the 12th through the 16th century, the area around Mariupol was largely devastated and depopulated by intense conflict between the Crimean Tatars, the Nogay Horde, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and Muscovy. By the middle of the 15th century much of the region north of the Black and Azov Seas was annexed by the Crimean Khanate and became a dependency of the Ottoman Empire. East of the Dnieper River a desolate steppe stretched to the Sea of Azov, where lack of water made early settlement precarious.[11] Being near the Muravsky Trail exposed it to frequent Crimean–Nogai slave raids and plundering by Tatar tribes, preventing permanent settlement and keeping it sparsely populated, or even entirely uninhabited, under Tatar rule. Hence it was known as the Wild Fields or the 'Deserted Plains' (Campi Deserti in Latin).[12][13]

Cossack period

[edit]In this region of Eurasian steppes, the Cossacks emerged as a distinct people in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Below the Dnieper Rapids were the Zaporozhian Cossacks, freebooters organized into small, loosely-knit, and highly mobile groups who were both livestock farmers and nomads. The Cossacks would regularly penetrate the steppe to fish and hunt, as well as for migratory farming and to herd livestock. Their independence from governmental and landowner authority attracted to join them many peasants and serfs fleeing the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Grand Duchy of Moscow.[citation needed]

The Treaty of Constantinople in 1700 further isolated the region, as it stipulated that there should be no settlements or fortifications on the coast of the Azov Sea to the mouth of the Mius River. In 1709, in response to a Cossack alliance with Sweden against Russia, Tsar Peter the Great ordered the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich, and their complete and permanent expulsion from the area.[14] In 1733, Russia was preparing for a new military campaign against the Ottoman Empire and therefore allowed the return of the Zaporozhians, although the territory officially belonged to Turkey.[15]

Under the Agreement of Lubny of 1734, the Zaporozhians regained all their former lands, and in return, were to serve in the Russian army in war. They were also permitted to build a new stockade[clarification needed] on the Dnieper River called New Sich, though the terms prohibited them from erecting fortifications. These terms allowed only for living quarters, in Ukrainian called kureni.[15]

Upon their return, the Zaporozhian population in these lands was extremely sparse, so effort to establish a measure of control, they introduced a structure of districts or palankas.[16] The nearest district to modern Mariupol was the Kalmius District, but its border did not extend to the mouth of the Kalmius River,[17] although this area had been part of its[clarification needed] migratory territory. After 1736, the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Don Cossacks (whose capital was at nearby Novoazovsk) came into conflict over the area, until Tsarina Elizabeth issued a decree in 1746 declaring the Kalmius River the dividing line between the two Cossack hosts.[18]

Sometime after 1738,[19][20] the treaties of Belgrade and Niš in 1739, in addition to the Russian-Turkish convention of 1741,[21] as well as the following likely concurrent land survey of 1743–1746 (resulting in the demarcation decree of 1746), the Zaporzhian Cossacks established a military outpost on "the high promontory on the right bank of the Kalmius river."[22] Though the details of its construction and history are obscure, excavations have revealed Cossack artifacts, including others, within the enclosure being approximately 120 square meters in the shape of a square.[23] The outpost was likely a modest structure in that it lay within the territory of the Ottoman Empire, and the erection of fortifications on the Sea of Azov was prohibited by the Treaty of Niš.[citation needed]

The last Tatar raid, launched in 1769, covered a vast area, overrunning the New Russian Province with a huge army in severe wintertime weather.[24][25] The raid destroyed the Kalmius fortifications and burned all the Cossack winter lodgings.[22] In 1770, the Russian government, during the war with Turkey, moved its border with the Crimean Khanate southwest by more than two hundred kilometres. This action initiated the Dnieper fortified line (running from today's Zaporizhzhia to Novopetrovka),[26] thereby laying claim to the region, including the site of future Mariupol, from the Ottoman Empire.

Following the victory of the Russian forces, the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca eliminated the endemic threat from Crimea.[27][28] In 1775, Zaporizhzhia was incorporated into the New Russian Governorate, and part of the land claimed behind the Dnieper fortified line including modern Mariupol was incorporated in the newly re-established Azov Governorate.[citation needed]

Russian Empire and Soviet Union

[edit]After the Russo-Turkish War from 1768 to 1774, the governor of the Azov Governorate, Vasily A. Chertkov, reported to Grigory Potemkin on 23 February 1776 that ruins of ancient domakhas (homes) had been found in the area, and in 1778 he planned the new town of Pavlovsk.[29] However, on 29 September 1779, the city of Marianοpol (Greek: Μαριανόπολη) in Kalmius County was founded on the site. For the Russian authorities the city was named after the Russian Empress Maria Feodorovna; its de facto title came from after the Greek settlement of Mariampol, a suburb of Bakhchysarai in Crimea. The name was derived from the Hodegetria icon of the Holy Theotokos and the Virgin Mary.[30][31] Subsequently, in 1780, Russian authorities forcibly relocated many Orthodox Greeks from Crimea to the Mariupol area, in what is known as the Emigration of Christians from the Crimea.[32]

In 1782, Mariupol was an administrative seat of its county in the Azov Governorate of the Russian Empire, with 2,948 inhabitants. In the early 19th century, a customs house, a church-parish school, a port authority building, a county religious school, and two privately founded girls' schools were built. By the 1850s the population had grown to 4,600 and the city had 120 shops and 15 wine cellars. In 1869, consuls and vice-consuls of Prussia, Sweden, Norway, Austria-Hungary, the Roman States, Italy, and France established their representative offices in Mariupol.[33][34]

After the construction of the railway line from Yuzovka (later Stalino and Donetsk) to Mariupol in 1882, much of the wheat grown in the Yekaterinoslav Governorate and coal from the Donets Basin were exported via the port of Mariupol (the second largest in the South Russian Empire after Odesa), which served as a key funding source for opening a hospital, public library, electric power station and urban water supply system.[citation needed]

Mariupol remained a local trading centre until 1898, when the Belgian subsidiary SA Providence Russe opened a steelworks in Sartana, a village near Mariupol (now the Ilyich Steel & Iron Works). The company incurred heavy losses and by 1902 was bankrupt, owing 6 million francs to the Providence company and needing to be re-financed by the Banque de l'Union Parisienne.[35] The mills brought cultural diversity to Mariupol as immigrants, mostly peasants from all over the empire, moved to the city looking for a job and a better life. The number of workers increased to 5,400.[citation needed]

In 1914, the population of Mariupol reached 58,000. However, the period from 1917 onwards saw a continuous decline in population and industry due to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War. In 1933, a new steelworks (Azovstal) was built along the Kalmius River.[citation needed]

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, the city was under German military occupation from 8 October 1941, to 10 September 1943.[37][38] During this time, the city suffered tremendous material damage and great loss of life. The Germans shot approximately 10,000 inhabitants,[39][better source needed] sent nearly 50,000 young men and girls as forced laborers to Germany and deported 36,000 prisoners to concentration camps.[citation needed]

During the occupation, the Germans focused on "the complete and quick destruction" of Mariupol's Jewish population, as part of the Holocaust.[37] The execution of the Jews of Mariupol was carried out by Sonderkommando 10A, which was part of Einsatzgruppe D. The leader was Obersturmbannführer Heinz Seetzen.[37] The Germans shot about 8,000 Mariupol Jews from 20 October 1941, to 21 October 1941.[37] By 21 November 1941, Mariupol was declared Jew-free.[37]

The "Menorah memorial", or officially, the Mariupol Memorial to the Murdered Jews[40] is installed in a suburb of Mariupol in memory to the murdered Jews of the city.[41][42] The work consists of a seven-pointed menorah, a Star of David and two commemorative steles with inscriptions in Russian:[40][43]

Victims of the fascist genocide were shot here – the Jews of Mariupol. October 1941. May their souls be connected with the living[b]

I will give in my house and within my walls a place and a name preferable to sons and daughters; I will give them an eternal name” (Isaiah 56:5)

The Choral Synagogue of Mariupol was reportedly undamaged during the hostilities. Reportedly, the Germans opened a hospital in the building, and when they retreated, tried to set fire to it.[44]

The Germans operated four transit camps for prisoners of war in Mariupol, consecutively Dulag 152 in 1941–1942, Dulag 172 in 1942, Dulag 190 in 1942–1943 and Dulag 201 in 1943, as well a subcamp of the Stalag 368 POW camp in 1943.[45] Mariupol was liberated by the Soviet Red Army on 10 September 1943.[38]

In 1948, Mariupol was renamed "Zhdanov", after the recently deceased close Stalin ally Andrei Zhdanov, who had been born in the city. The historic name of the city "Mariupol" was restored in 1989 after a popular grassroots movement advocated for the name change.[46]

Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]War in Donbas and economic downturn

[edit]

Following the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity in 2014, pro-Russian movements and protests erupted across eastern Ukraine, including Mariupol. This unrest later evolved into the Russo-Ukrainian War between the Ukrainian government and Russia together with the separatist forces of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic (DPR). In May of that year, a battle between the two sides broke out in Mariupol after it briefly came under DPR control.[47] On 13 June 2014, the city was recaptured by government forces,[48] and, in June 2015, Mariupol was proclaimed the temporary administrative centre of Donetsk Oblast until the city of Donetsk could be recaptured by the Ukrainian forces.[49][non-primary source needed]

The city remained peaceful until the end of August 2014, when DPR separatists together with a detachment of the Russian Armed Forces captured Novoazovsk, located 45 kilometres (28 mi) east of Mariupol near the Russo-Ukrainian border.[50] This followed an offensive by pro-Russian forces from the east, which came within 16 kilometres (10 mi) of Mariupol, before an overnight counter-offensive pushed the separatists away from the city.[51] In September, the two sides agreed to a ceasefire, halting that offensive. Minor skirmishes continued on the outskirts of Mariupol in the following months.[51]

A rocket attack on Mariupol was launched on 24 January 2015 by the Donetsk People's Republic,[52] from the village of Shyrokyne around 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) east of Mariupol city limits.[53] Grad rockets fired by separatist forces hit residential areas of Mariupol, killing at least 30 people.[54] A Bellingcat investigative team concluded that the shelling was instructed, directed and supervised by Russian military commanders in active service with the Russian Ministry of Defence.[55] The attack exposed the city's vulnerability to separatist attacks. As a result, in February 2015, Ukrainian forces launched an surprise assault on Shyrokyne,[56] forcing the separatists out from Shyrokyne and neighbouring villages by July 2015.[57]

In May 2018, the Crimean Bridge was opened, linking mainland Russia to Crimea, which had been annexed in 2014 in the opening stages of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[58] Russia "dramatically increased" the number of armed vessels in the Kerch Strait in 2018, and cargo ships bound for Mariupol found themselves subject to inspections by Russian authorities, resulting in delays of up to a week.[58] Therefore, Mariupol port workers were put on a four-day week schedule.[58] On 26 October 2018, The Globe and Mail reported that the bridge had reduced Ukrainian shipping from its Azov Sea ports (including Mariupol) by about 25%.[59]

2022 Russian siege and subsequent occupation

[edit]During the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine of 2022, Mariupol was a strategic target for Russian forces and their proxies.[60] It came under artillery bombardment the day the invasion began,[61] and was placed under siege by Russian forces.[62] By early March, a severe humanitarian crisis developed in the city,[63][64] which a Red Cross worker later described as "apocalyptic", citing food shortages and severe damage to infrastructure and access to sanitation.[65] The siege was also marked by numerous war crimes committed by Russian forces,[66] most notably Russian airstrikes on a maternity hospital[67][68] and a drama theater serving as an air raid shelter for hundreds of civilians.[69]

By late April, Russian and separatist troops had pushed deep into most of the city, separating the last Ukrainian troops from the few pockets of Ukrainian troops retreating into the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works, which contains a complex of bunkers and tunnels which could even resist a nuclear bombing.[70] Ukrainian troops in Azovstal held out until 16 May 2022, when its last troops from the Azovstal Steel Plant surrendered and the city fell into Russian control.[71][72]

When the fighting stopped, "as many as 90%" of residential buildings in Mariupol had been damaged or destroyed, according to the United Nations (UN)[73] and Ukrainian authorities.[74] Estimates for the number of civilian dead ranged from the UN's list of 1,348 confirmed deaths[75][76][77] to the Ukrainian claim of over 25,000.[78] Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky awarded Mariupol the title of Hero City of Ukraine due to Ukrainian forces' "valiant defense" of the city.[79]

In the months after they took control of the city, Russian authorities had many damaged buildings torn down, sometimes evicting the remaining residents. Some new housing was also built. Associated Press described this ongoing process as an effort to "eradicat[e] all vestiges of Ukraine" and to cover up "the evidence of war crimes". Local schools started using a Russian curriculum, the television and radio broadcasts switched to Russian, and many street names were replaced by their Soviet-era names.[80] The latter was especially controversial, as the Ukrainian authorities restored many historic names during the decommunization process, all of which predated the Soviet Union.[81] Among other toponyms, "Freedom Square" was renamed "Lenin Square".[82]

In August 2023, the Institute for the Study of War reported that the Ukrainian Resistance Center had claimed to have gained access to documents detailing Russian plans to conduct a decade-long ethnic cleansing campaign in occupied Mariupol. The ISW reported that the depopulation of Ukrainians through deportation and Russian efforts to attract Russian citizens to move to the city is likely to be an ethnic cleansing campaign in addition to being apparent violations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.[83]

The estimates of the pre-war population that remained in the city in 2024 vary from 80,000 to 120,000.[84][85][86] Since the invasion is estimated to have damaged over 90% of housing in the city centre, the Russian government has invested significant amounts towards building new buildings. This process has included demolishing many damaged buildings, whose remaining residents are sometimes not allowed into the rebuilt buildings, and are offered new property further from the city centre with little compensation. Property prices are similar to before the war, with the Russian government maintaining mortgages at 2% to draw in Russian buyers. According to a Ukrainian official, they number around 80,000 as of mid-2024. In early 2024, the Russian government began a process to seize properties from those who had fled, requiring owners to obtain Russian citizenship and re-register properties with Russian authorities in person in order to keep them. 514 apartments were declared ownerless in May.[86]

The 2023 Ukrainian documentary about the siege, 20 Days in Mariupol, won the 2024 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film.[87]

In November 2024, Ukrainian MP Maxym Tkachenko claimed that around one third of the estimated 200,000 people that fled Mariupol during the city's siege had returned to living in the city, primarily due to inadequate government support when living elsewhere.[88] A day later, he said that "There is no such data. It was my unfounded and emotional assumption."[89][90]

Geography

[edit]Mariupol is located in the south of the Donetsk Oblast, on the coast of Sea of Azov and at the mouth of Kalmius River. It is located in an area of the Azov Lowland that is an extension of the Ukrainian Black Sea Lowland. To the east of Mariupol is the Khomutov Steppe, which is also part of the Azov Lowland, located on the border with Russia.

The city occupies an area of 166 km2 (64 sq mi), or 244 km2 (94 sq mi) including suburbs administered by the city council. The downtown area is 106 km2 (41 sq mi), while the area of parks and gardens is 80.6 km2 (31.1 sq mi).

The city is mainly built on land made of solonetzic (sodium enriched) chernozem, with a significant amount of underground subsoil water, that frequently leads to landslides.

Climate

[edit]Mariupol has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with warm summers and cold winters. The average annual precipitation is 511 millimetres (20 in). Agroclimatic conditions allow the cultivation of warmth-loving agricultural crops with long vegetative periods (sunflower, melons, grapes, etc.). However water resources in the region are insufficient, so ponds and water basins are used for the needs of the population and industry.

In winter, the wind blows mainly from the east, and in summer the north.

| Climate data for Mariupol (1991–2020, extremes 1955–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.7 (33.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.1 (32.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−3 (27) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.2 (−17.0) |

−25 (−13) |

−20 (−4) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−8 (18) |

−17 (1) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.9 (1.89) |

42.4 (1.67) |

39.3 (1.55) |

38.7 (1.52) |

38.4 (1.51) |

56.4 (2.22) |

46.3 (1.82) |

37.0 (1.46) |

44.3 (1.74) |

33.7 (1.33) |

49.3 (1.94) |

52.2 (2.06) |

525.9 (20.70) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.3 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 77.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.8 | 85.6 | 83.0 | 76.4 | 71.6 | 70.9 | 66.7 | 64.9 | 70.0 | 78.2 | 87.1 | 88.3 | 77.5 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net (temperatures and record high and low)[91] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation and humidity 1981–2010)[92] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]

Mariupol has historically led Ukraine in the volume of emissions of harmful substances by industrial enterprises. The city's leading enterprises have begun to address these ecological problems, so, over the last 15 years, industrial emissions have fallen to nearly a half of their previous levels.

Due to stable production by the majority of the large industrial enterprises, the city constantly experiences environmental problems. At the end of the 1970s, Zhdanov (Mariupol) ranked third in the USSR (after Novokuznetsk and Magnitogorsk) in the quantity of industrial emissions. In 1989, including all enterprises, the city had 5,215 sources of atmospheric pollution producing 752,900 tons of harmful substances a year (about 98% from metallurgical enterprises and Mariupol Coke-Chemical Plant "Markokhim"). Even after Ukraine regained independence in 1991, by the mid-1990s many pollution limits were still exceeded:

- 1.3 times for ammonia

- 1.3 times for phenol

- 2.0 times for formaldehyde

In the residential areas adjoining the industrial giants, concentrations of benzopyrene reach 6–9 times the maximum concentration limits; hydrogen fluoride, ammonia, and formaldehyde reach 2–3 to 5 times the maximum concentration limits; dust and oxides of carbon, and hydrogen sulphide are 6–8 times the maximum concentration limits; and dioxides of nitrogen are 2–3 times the maximum concentration limits. The maximum concentration limit has been exceed on phenol by 17x, and on benzapiren by 13-14x.

Ill-considered locations of the Azovstal and Markokhim to economize on transport charges, during both construction in the 1930s and subsequent operations, have led to extensive wind-borne emissions into the central areas of Mariupol. Wind intensity and geographical "flatness" offer relief from the accumulation of long-standing pollutants, somewhat easing the problem.

The nearby Sea of Azov is in distress. The fish catch in the area has been reduced by orders of magnitude over the last 30–40 years.

The environmental protection activity of the leading industrial enterprises in Mariupol costs millions of hrivnas, but it appears to have little effect on the city's long-standing environmental problems.

Governance

[edit]City administration and local politics

[edit]

The Mariupol electorate traditionally supported left wing (socialist and communist) and pro-Russian political parties. At the turn of the 21st century the Party of Regions numerically prevailed in the Mariupol City Council, followed by the Socialist Party of Ukraine. Besides the city council, the local population in Mariupol also vote for deputies in the Donetsk Oblast Council on a regional level and the Verkhovna Rada on a national level.

In the presidential elections of 2004, 91.1% of the city voted for Viktor Yanukovych and 5.93% for Viktor Yuschenko. In the 2006 parliamentary elections, the city voted for the Party of Regions with 39.72% of the votes, the Socialist Party of Ukraine with 20.38%, the Natalia Vitrenko Block with 9.53%, and the Communist Party of Ukraine with 3.29%.

In the 2014 parliamentary elections the Opposition Bloc won more than 50% of the votes.[93] The seats of the city's two electoral districts were won by Serhiy Matviyenkov and Serhiy Taruta.[94]

The de jure mayor (chairman of executive committee of the city council) of the city is Ukrainian politician Vadym Boychenko.[2] In the October 2020 local elections he was re-elected with 64.57% of the votes as a candidate of the Vadym Boychenko Bloc.[2] In these mayoral elections Volodymyr Klymenko of Opposition Platform — For Life received 25.84% of the vote, self-nominated candidate Lydia Mugli received 4.72%, the candidate from For the Future Yulia Bashkirova received 1.68% and the nominee from Our Land Mykhailo Klyuyev received 0.99% of the votes.[2] Voter turnout in the election was 27%.[95]

In the concurrent election in the council, the Opposition Bloc received a landslide victory. Out of a total of 54 deputies, 45 of them were part of the Opposition Bloc party, 5 were from Power of the People party, and 4 from Our Land party.[96]

On 6 April 2022, amidst the siege of the city, politician Konstantin Ivashchenko was installed by Russia as the mayor of Mariupol.[97] He served as the de facto mayor until January 2023, when he was replaced with Oleg Morgun.[98]

Administrative division

[edit]

Populated places:

1 — Sartana

2 — Staryi Krym

3 — Talakivka

4 — Hnutove

5 — Lomakyne

Mariupol is divided into four urban districts.

- Kalmiuskyi District (until June 2016 named Illichivsk District after Vladimir Ilyich Lenin[99]) is the northern part of the city, the largest and most industrialized neighborhood in the city. It is commonly known as the Zavod ("Factory") of Ilyich.

- Livoberezhnyi District (until June 2016 named after Sergo Ordzhonikidze[99]) is the eastern part of the city, on the left bank of the Kalmius River. Its name means the "Left Bank".

- Prymorskyi District is the southern area of the city, on the coast of the Azov Sea. The everyday name of the central part this neighbourhood is simply "the Port".

- Tsentralnyi District is the central urban district. Its everyday name is simply "the Centre" or "the City". Formerly it was known as Zhovtnevyi District (October District) commemorating the 1917 Bolshevik revolution.

The Kalmius River separates the Livoberezhnyi District from the remaining three districts. The population is mostly concentrated in the Tsentralnyi and Prymorskyi Districts. The Kalmiuskyi District houses the large Illich Steel and Iron Works and the Azovmash manufacturing plant. The Livoberezhnyi (Left Bank) is home to the Azovstal metallurgic combine and the Koksokhim (Coke and Chemical) factory. The settlements of Staryi Krym and Sartana are located in close proximity to the city limits of Mariupol (see map).

Coat of arms

[edit]The modern coat of arms of Mariupol was confirmed in 1989. It is described in heraldic terms as: Per fess wavy argent and azure, on an anchor or, accompanied by the figure 1778 of the last. The gold anchor has a ring on top. The number 1778 indicates the year of the city's founding. The argent represents steel; the azure, the sea; the anchor, the port; and the ring, metallurgy.

City holidays

[edit]Holidays exclusive to Mariupol include:

- Day of liberation of the city from fascist aggressors (on 10 September)

- Day of the city (the Sunday after the day of liberation of Mariupol in September)

- Day of the metallurgist – a professional holiday for many citizens

- Day of the machine engineer

- Day of the seaman and other professional holidays

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 31,116 | — |

| 1926 | 40,825 | +31.2% |

| 1939 | 223,796 | +448.2% |

| 1959 | 283,570 | +26.7% |

| 1970 | 416,927 | +47.0% |

| 1979 | 502,581 | +20.5% |

| 1989 | 518,933 | +3.3% |

| 2001 | 492,176 | −5.2% |

| 2011 | 466,665 | −5.2% |

| 2022 | 425,681 | −8.8% |

| Source: [100] | ||

As of 1 December 2014, the city's population was 477,992. Over the last century the population has grown nearly twelvefold. The city is populated by Ukrainians, Russians, Pontic Greeks (including Caucasus Greeks and Tatar- and Turkish-speaking but Greek Orthodox Christian Urums), Belarusians, Armenians, Jews, etc. The main language is Russian.

The population fell precipitously as the result of the siege of the city in 2022. Per Ukrainian sources it was 120 thousand in 2023, while according to Russian administration the city population was approximately 280 thousand.[4][101]

Ethnic structure

[edit]The city is largely and traditionally Russian-speaking, while ethnically the population is divided about evenly between Ukrainians and Russians. There is also a significant ethnic Greek minority in the city.

In 2002, ethnic Ukrainians made up the largest percentage (48.7%) but less than half of the population; the second greatest ethnicity was Russian (44.4%). A June–July 2017 survey indicated that Ukrainians had grown to 59% of Mariupol's population and the Russian share had dropped to 33%.[102]

The city is home to the largest population of Pontic Greeks in Ukraine ("Greeks of Priazovye") at 21,900, with 31,400 more in the six nearby rural areas, totaling about 70% of the Pontic Greek population of the area and 60% for the country.

| Ethnicity | Number of people | Percent of population |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 248,683 | 48.7 |

| Russian | 226,848 | 44.4 |

| Greeks | 21,923 | 4.3 |

| Belarusian | 3,858 | 0.8 |

| Armenian | 1,205 | 0.2 |

| Jews | 1,176 | 0.2 |

| Bulgarian | 1,082 | 0.2 |

| other | 6,060 | 1.2 |

| All population | 510,835 | 100 |

Language structure

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (August 2009) |

The city is predominantly Russian speaking. From 60% to 80% of Ukrainian-language inhabitants communicate in Surzhyk, due to the large influence of Russian culture.

Most Greek-speaking villages in the region speak a dialect called Rumeíka, a branch of Pontic Greek. About 17 villages speak this language today. Modern scholars distinguish five subdialects of Rumeíka according to their similarity to standard Modern Greek. This was derived from the dialect of the original Pontic settlers from the Crimea. Although Rumeíka is often described as a Pontic dialect, the situation is more nuanced. Arguments can be brought both for Rumeíka's similarity to Pontic Greek and to the Northern Greek dialects. In the view of Maxim Kisilier, while the Rumeíka dialect shares some features with both the Pontic Greek and the Northern Greek dialects, it is better considered on its own terms as a separate Greek dialect, or even a group of dialects.[103]

The village of Anadol speaks Pontic proper, being settled from the Pontos in the 19th century. After the October Revolution of 1917, a Rumaiic revival occurred in the region. The Soviet administration established a Greek-Rumaiic theater, several magazines and a newspaper, and a number of Rumaiic language schools. The best Rumaiic poet Georgi Kostoprav created a Rumaiic poetic language for his work. This process was reversed in 1937 as Kostoprav and many other Rumaiics and Urums were killed as part of Joseph Stalin's national policies.[104]

A new attempt to preserve a sense of ethnic Rumaiic identity started in the mid-1980s. The Ukrainian scholar Andriy Biletsky created a new Slavonic alphabet for Greek speakers. Though a number of writers and poets make use of this alphabet, the population of the region rarely uses it. The Rumaiic language is declining rapidly, most endangered by the standard Modern Greek which is taught in schools and the local university. The latest investigations by Alexandra Gromova demonstrate that there is still hope that elements of the Rumaiic population will continue to use the dialect.[104]

Along with those speaking Rumeíka, there were and are a number of Tatar-speaking Orthodox villages, the so-called Urums, which is the Tatar term for Romaios or Rumei. This subdivision had already occurred in Crimea before the settlement of the Azov Sea steppe region by Pontic Greeks which began following the fall of the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia in 1461. It occurred on a larger scale after the end of the Russo-Turkish War in 1779, as part of the Russian policy to populate and develop the region while depriving the Crimea of an economically active part of its population. Though Greek- and Tatar-speaking settlers lived separately, the language of the Urums was the lingua franca of the region for a long time, being called the language of the bazaar.

There are also a number of settlements of other ethnic communities, including Germans, Bulgarians, and Albanians (though the meanings of all such terms in this context is open to dispute).

Native languages of the population as of the All-Russian Empire Census in 1897:[105]

| Language | The city of Mariupol |

|---|---|

| Russian | 19,670 |

| Ukrainian | 3,125 |

| Greek | 1,590 |

| Turkish | 922 |

| Total Population | 31,116 |

| Language | Number (person) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Russian | 457,931 | 89.64 |

| Ukrainian | 50,656 | 9.92 |

| Greek (Mariupol Greek and Urum) | 1,046 | 0.20 |

| Armenian | 372 | 0.07 |

| Belarusian | 266 | 0.05 |

| Bulgarian | 55 | 0.01 |

| other | 509 | 0.10 |

| All population | 510,835 | 100 |

Religious communities

[edit]

- 11 churches of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchy.

- 3 churches of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchy.

- 52 various religious communities.

The city is adorned by the St. Nicholas Cathedral (in the Tsentralnyi borough) and other churches of the city, namely:

- St. Nicholas (Primorsky borough)

- St. Michael (Livoberezhnyi borough)

- St. Preobrazheniye ("Holy Transfiguration") (Primorsky borough)

- St. Ilya (Ilyichevsky borough)

- Uspensky ("Assumption") (Livoberezhnyi borough)

- St. Vladimir (Livoberezhnyi borough)

- St. Amvrosy Optinsky (Illyichevsky borough, Volonterobvka)

- St. Varlampy (Illyichevsky borough, Mirny)

- St. George (Illyichevsky borough, Sartana)

- Nativity of the Virgin Mary (Illyichevsky borough, Talakovka)

- St. Boris & Gleb (Prymorsky borough, Moryakov)

Many churches were destroyed in the 1930s during the Soviet era by the Bolshevik government as part of the Atheist Five-Year Plan:[107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118]

- Church of the Assumption of Mary[116][117][107][108][119][120]

- Church of Mary Magdalene[121][122]

- Tsarevich Chapel in Mariupol

- Roman Catholic church also known as "the church of the Italians" was built in 1860. The Italians in Mariupol exported grain and imported citrus fruits and spices. In Soviet times the church was destroyed in 1936.[114][115][123][124]

- Saints Constantine and Helen Church

- Cathedral of St. Charalambos[125][126][127]

- Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection

- Church of the Nativity of the Virgin

New buildings:

- Cathedral of Saint Nicholas

- Cathedral of Saint Michael the Archangel

- Cathedral of Saint George, built in 2005

- Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection

-

Roman Catholic church

-

Cathedral of Saint George

-

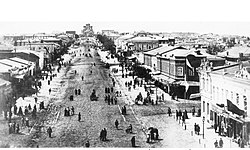

Market square

-

Catherine Street

In addition to churches, there are 3 mosques around the city.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]Employment

[edit]In 2009, the official rate of unemployment in the city was 2%.[128] The figure, however, only includes people registered as "unemployed" in the local job centre. The real unemployment rate was therefore higher.

| Year | Unemployment (% of labor force) |

|---|---|

| 2006 | 0.4

|

| 2007 | 0.4

|

| 2008 | 1.2

|

| 2009 | 2.0

|

Industry

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

There were 56 industrial enterprises in Mariupol under various plans of ownership. The city's industry was diverse, with heavy industry dominant. Mariupol was home to major steel mills (including some of global importance) and chemical plants; there was also an important seaport and a railroad junction. The largest enterprises were Ilyich Iron and Steel Works, Azovstal, Azovmash Holding, and the Mariupol Sea Trading Port. There were also shipyards, fish canneries, and various educational institutions with studies in metallurgy and science.

The total industrial production of the city for eight months in 2005 (January – August) was 21378.2 million hryvnas (US$4.233 billion), compared to 1999 – 6169.806 million hryvnas (US$1.222 billion). This was 37.5% of the total production for Donetsk Oblast. The leading business of the city was ferrous metallurgy, which made up 93.5% of the city's income from industrial production. The annual output estimates are in millions of tonnes of iron, steel, rolled iron, and agglomerate.

- Illich Steel and Iron Works (Mariupol Metallurgical Combine named Ilyich) was an integrated mill, with all the facilities for a full metallurgical cycle. Housing around 100 thousand workers, it wa the second largest in Ukraine, after Kryvorizhstal. The company was the collective property of the Society of Tenants (Joint-Stock Company "Ilyich-steel"; with about 37,000 worker-shareholders). The head of the board of enterprise was the People's Deputy, Volodymyr Boyko. The enterprise had multiple structural divisions: Management of Public Catering and Trade ("УОПТ", a network of 52 enterprises), a chemist's network Ilyich-Pharm, more than 50 agro shops (former collective farms of the south of Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts), the office of the Komsomol Mines, various machine-building enterprises in the Cherkasy Oblast, Mariupol International Airport, and the Mariupol Television Network (locally known as MTV).

- Azovstal was another integrated mill ("Combine"), the third largest in Ukraine in terms of gross revenue. Its production varied in millions of tonnes of pig-iron, steel, and rolled iron annually. The company's general director was Oleksiy Bilyi. Azovstal was closely connected with the Mariupol coke works, "Markokhim", which served as its supplier of coke.

- Open Society Azovmash (Holding) was the largest machine-building enterprise in Ukraine, specialising in production of equipment for mining-metallurgical complexes, tank cars, port cranes, boilers, fuel-fillers, etc. The President was Oleksandr Savchuk. The enterprise was formerly owned by the state and was privatised by System Capital Management, a Donetsk financial and economic group.

- Azov ship-repair factory (АСРЗ) was the largest enterprise of its class on the Sea of Azov, also owned by System Capital Management.

- Open Society Mariupol sea trading port was the largest sea port in eastern Ukraine through which was transported large quantities of various products such as coal, metal, mechanical engineering products, varieties of ores and grains from and to various cities such as Donetsk, Kharkiv, Luhansk, and the near regions of the Russian Federation.

- Azov sea shipping company which was owned until 2003 by the Donbass Merchant Marine fleet, is now also under the ownership of System Capital Management. Donbass Merchant Marine is now a bankrupt enterprise which formerly operated out of ports on the Sea of Azov such as Mariupol, Berdiansk, and Taganrog (Russia).

The above-mentioned enterprises, along with a plethora of others not mentioned, are located in the free economic zone of Azov.

Finances

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

The GDP of the city in 2004 was ₴22,769,400 ($4,510,400); it is listed in the state budget as ₴83,332,000 ($16,507,400). The city is one of the largest contributors to the Ukrainian national budget (after Kyiv and Zaporizhzhia).

The GPA of the city is ₴1,262.04 (~US$250.00) a month, one of the highest in the country. The average pension in the city is ₴423.15 ($83.82). Commercial debts in the city were reduced in 2005 to 1.1% or ₴5.1 million ($1.01 million).

Income from services rendered for 9 months of 2005 was ₴860.4 million ($107.4 million) and the volume of retail trade for the same period was ₴838.7 million ($166.1 million). The city's enterprises for 9 months of 2005 recorded a positive financial result (profit) of ₴3.2 billion ($634 million), which is 23.6% more than in the prior year (2004).

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

Cultural institutions

[edit]- Theatres

- Donetsk Regional Drama Theatre. In 2003 the oldest theater in the region celebrated its 125th anniversary.[132] For its contribution to the spiritual education of theater, in 2000 it was awarded the laureate in the "Gold Scythian" competition. The theatre was largely destroyed by Russian airstrikes on 16 March 2022.[133]

- Cinemas

- Pobeda ("Victory") – now closed

- Savona

- Multiplex

Palaces of culture (recreation centres) (together with clubs – 16):

- Metallurgov ("Metallurgists") of Ilyich Steel & Iron Works

- Azovstal of Azovstal Steel & Iron Works

- Iskra ("Spark") of Azovmash Machine-builder Concern

- MarKokhim (Mariupol Coke Chemistry)

- Moryakov ("Sailors")

- Stroitel ("Builders")

- Palace of children's and youth art ("Palace of Children art")

- Municipal Palace of Culture

- Showrooms and museums

- Mariupol Regional Museum

- Kuindzhi Art Exhibition

- Museum of Folk Life (formerly, the museum of Andrey Zhdanov)

- Museum halls of the industrial enterprises and their divisions, establishments and the organisations of city, and others.

- Libraries (35)

- Korolenko Central Library;

- Gorky Central Children's Library;

- Serafimovich Library (The oldest library in the city);

- And also: Gaydar Library, Honchar Library, Hrushevsky Library, Krupskaya Library, Kuprin Library, Lesya Ukrainka Library, Marshak Library, Morozov Library, Novikov-Priboy Library, Pushkin Library, Svetlov Library, Turgenev Library, Franko Library, Chekhov Library, Chukovsky Library, the libraries of industrial enterprises, establishments, and the organisations of the city.

Art and literature

[edit]Creative Organisations of Artists, Union of Journalists of Mariupol, the Literary Union «Azovye» (from 1924, about 100 members), and others. Works of Mariupol poets and writers: N. Berilov, A. Belous, G. Moroz, A. Shapurmi, A. Savchenko, V. Kior, N. Harakoz, L. Kiryakov, L. Belozerova, P. Bessonov, and A. Zaruba are written in the Russian, Ukrainian, and Greek languages. Presently, 10 members of the National Union of Writers of Ukraine live in the city.

Festivals

[edit]

From 2017 Mariupol has hosted the MRPL City Festival, an annual music festival, held every August on Pishchanka beach. The festival began in 2017 as "the biggest event on the East Coast." The festival is multi-genre: each scene has its own style.[134][135]

Gogolfest is an annual multidisciplinary international festival of contemporary art, which contains theatrical performances, day and night musical performances, film shows, art exhibitions and dialogues. In 2018–2019 Gogolfest was held in Mariupol. In 2019 the festival lasted from 26 April to 1 May 2019.[136]

Tourism and attractions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

Tourist attractions are mainly on the coast of the Sea of Azov. Around the city a strip of resort settlements was established: Melekino, Urzuf, Yalta, Donetsk Oblast, Sedovo, Bezymennoye, Sopino, Belosaray Kosa,

The first resorts in the city opened in 1926. Along the sea a narrow bar of sandy beaches stretches for 16 km. Water temperature in the summer ranges from 22 to 24 °C (72–75 °F). The duration of the bathing season is 120 days.

Parks

[edit]

- City Square (Theatrical Square)

- Extreme Park (new attractions near to the biggest in city of the Palace of Culture of Metallurgists)

- Gurov Meadow-park (former Meadow-park a name of the 200-anniversary of Mariupol)

- City Garden ("Children's Central Public Garden")

- Veselka Park (Livoberezhnyi District), named for the rainbow

- Azovstal Park (Livoberezhnyi District)

- Petrovsky Park (near the modern Volodymyr Boiko Stadium and constructions of "Azovmash" basketball club, Kalmiuskyi District)

- Primorsky Park (Prymorsky District)

Monuments

[edit]Mariupol has monuments to Vladimir Vysotsky, and in honour of the liberation of Donbass, the metallurgists, and others.

The city of Mariupol has several parks and squares, the most popular being the City Square (Theater Square), the Amusement Park, the Gurov Park (formerly Mariupol Bicentenary Park), the Petrovski Park, the City Gardens (with monuments to the heroes of the Second World War, inaugurated in 1863, the Vessiolka park, the Azovstal park, the Sea park (formerly of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the October Revolution).

Mariupol is known for its many memorials, statues and sculptures, including the bust of Mariupol-born painter Arkhip Kuindzhi, a statue of Taras Shevchenko, founder of the Ukrainian literary language in the second half of the 19th century, as well as Pushkin, representing the Russian language. Four statues of Lenin remain as testimonies to history. A statue of Andrei Zhdanov after whom the city was named from 1948 to 1990, dominated the central square of the city in the Soviet period but was removed in 1990. A statue of the iconoclastic singer Vladimir Vysotsky (former husband of the Russian-French actress Marina Vlady), was inaugurated in 1998. A bust of the winner of the White Army, commander of a battalion in the region in April 1919, Kuzma Anatov, was inaugurated in 1968 on the street of the same name.

The Great Patriotic War is the subject of some fifteen monuments, statues, tanks, busts, etc. in honor of the Red Army, a fighting unit, a glorious deed or a hero who died in combat to liberate the country from the Third Reich, such as the monument to the twelve patriots shot by the Germans on 7 March 1942.

A large statue commemorating the liberation of Donbass dominates the square on Nakhimov Avenue. The eternal flame burns before the monument to the victims of Nazism. A monument to the victims of Stalinism was erected on Theatre Square, as well as a large cross in 2008 at the main cemetery, in memory of the victims of the great famine of the 1920s following dekulakisation. A large stone with a commemorative plaque, in an alley off Lenin Avenue, commemorates the victims of Chernobyl.

There are also monuments to Makar Maza, Hryhoriy Yuriyovych Horban, K.P. Apatov, and Tolya Balabukha, to seamen–commandos, to pilots V.G. Semenyshyn and N.E. Lavytsky, and to soldiers of the Soviet 9th Aviation Division. The artists V. Konstantynov and L. Kuzminkov are the sculptors of some of the monuments, including the monument to Metropolitan Ignatiy, the founder of Mariupol, (1715–1786, canonized in 1998 by the Orthodox Church) recently erected near St. Nicholas Cathedral.

Infrastructure

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (April 2022) |

Mariupol is the second most populous city in Donetsk Oblast after Donetsk, and is amongst the ten most populous cities in Ukraine. See the list of cities in Ukraine.

Architecture and construction

[edit]

Old Mariupol is an area defined by the coast of the Sea of Azov to the south, the Kalmius River to the east, to the north by Shevchenko Boulevard, and to the west by Metalurhiv Avenue. It is made up mainly of low-rise buildings and has kept its pre-revolutionary architecture. Only Artem Street and Miru Avenue were built after World War II.

The central area of Mariupol (from Metalurhiv Avenue up to Budivelnykiv Avenue) is made up almost entirely of administrative and commercial buildings, including a city council building, a post office, the Lukov cinema, Mariupol State University of Humanities, Priazov State Technical University, the Korolenko central city library, and many large stores.

The architecture of other residential areas (Zakhidny, Skhidny, Kirov, Cheremushky, and 5th and 17th quarters) is not particularly distinctive or original and consists of typical apartment buildings of five to nine storeys.

The term "Cheremushki" carries a special meaning in Russian culture and now also in Ukrainian; it usually refers to the newly settled parts of a city. The city's residential area covers 9.82 million square meters. The population density is 19.3 square meters per inhabitant.

Industrial construction prevails. Mass building of habitable quarters within the city ended in the 1980s. Mainly under construction now are comfortable habitations.[clarification needed] The city's construction industry for nine months of 2005 executed a volume of civil contract and building works of 304.4 million hrivnas (US$60 million). The city density on this parameter is 22.1%.[clarification needed]

Mariupol has been almost completely destroyed during the ongoing Russian Invasion of Ukraine.[137]

Main streets

[edit]- Avenues: Miru, Metalurhiv, Budivelnykiv, Ilyich, Nakhimov, Peremohy, Lunin, and Leningradsky (in Livoberezhnyi District)

- Streets: Artem, Torhova, Apatov, Kuprin, Uritsky, Bakhchivandzhi, Gagarin, Karpinsky, Mamin-Sibiryak, Taganrog, Olympic, Azovstal, Makar Mazay, Karl Liebknecht

- Boulevards: Shevchenko, Morskyi, Prymore, Khmelnytskyi, etc.

- Squares: Administrative, Nezalezhnosti, Peremohy, Mashinobudivnykiv, Vioniv, Vyzvolennia.

Transportation

[edit]- Mariupol railway station: The city is connected by rail to Donbass (the Direction of trains being: Moscow, Kyiv, Lviv, Saint Petersburg, Minsk, Bryansk, Voronezh, Kharkiv, Poltava, Slavyansk-na-Kubani).

- A marina near the Port of Mariupol.

- Mariupol International Airport (the property Ilyich Mariupol steel and iron works).

City transport

[edit]

Mariupol has transportation including bus transportation, trolleybuses, trams, and fixed-route taxis. The city is connected by railways, a seaport and the airport to other countries and cities.

- Urban electric transport (MTTU, Mariupol Tram-trolleybus management):

- Trams, streetcars (since 1933) – 12 routes (models of type KTM-5 and KTM-8 operate),

- Trolleybuses (since 1970) – 14 routes (machines of type: Škoda 14Tr, ZiU-10, ZiU-9, YuMZ T-1, YuMZ T-2, de:MAN SL 172 HO).

- Buses – mainly marshrutka (private minibuses), on suburban and long-distance routes.

- Road service station (which includes transportations to Taganrog, Rostov-upon-Don, Krasnodar, Kyiv, Odesa, Yalta, Dnipro are carried out, etc.) and a suburban auto station (with routes to Pershotravnevy, Volodarsky and areas of Donetsk oblast).

Communications

[edit]All leading Ukrainian mobile communications carriers have served Mariupol. In Soviet times, ten automatic telephone exchanges were operational; six digital automatic telephone exchanges were recently added.

Health service

[edit]There are 60 medical and medical-health establishments in the city — hospitals, polyclinics, the station of blood transfusion, urgent care clinics, sanatoriums, sanatoriums-preventive clinics, regional centre of social maintenance of pensionaries and invalids, city centres: gastroenterology, thoracic surgery, bleedings, pancreatic, microsurgery of the eye. Central pool-hospital on a water-carriage. The largest hospital is the Mariupol regional intensive care hospital.

Education

[edit]Eight-one general educational establishments operated in Mariupol, including: 67 comprehensive schools (48,500 students), two grammar schools, three lyceums, four evening schools, three boarding schools, two private schools, eleven professional educational institutions (6,274 students), and 94 children's preschool establishments (12,700 children).

Three higher education establishments:

- Priazovsky State Technical University

- Mariupol State University

- Azovsky Institute of Marine Transport

Local media

[edit]

More than 20 local newspapers are published, mostly in Russian, including:

- Priazovsky Rabochy (Priazovdky Worker)

- Mariupolskaya Zhizn (Mariupol Life)

- Mariupolskaya Nedelya (Mariupol Week)

- Ilyichevets

- Azovstalets

- Azovsky Moryak (Azov Seaman)

- Azovsky Mashinostroitel (Azov Machine-builder)

Twelve radio stations, and seven regional television companies and channels:

- Sigma Broadcasting Company

- MTV Broadcasting Company (Mariupol television)

- TV 7 Broadcasting Company

- Inter-Mariupol Broadcasting Company

- Format Broadcasting Company

Retransmitting about 15 national public channels (Inter, 1+1, STB, NTN, 5 Channel, ICTV, First National TV, New Channel, TV Company Ukraina, etc.)

Public organizations

[edit]There are about 300 public associations, including 22 trade-union organizations, about 40 political parties, 16 youth groups, four women's organizations, 37 associations of veterans and disabled, and 134 national and cultural societies.[citation needed]

Sports

[edit]

Mariupol is the hometown of the nationally famous swimmer Oleksandr Sydorenko who lived in the city until his death on 20 February 2022.[138][unreliable source?]

FC Mariupol is a football club, with a great sport traditions and a history of participation at the European level competitions.

The water polo team, the "Ilyichevets", is the undisputed champion of Ukraine. It has won the Ukrainian championship 11 times. Every year it plays in the European Champion Cup and Russian championship.

Azovstal' Canoeing Club on the Kalmius River. Vitaly Yepishkin – third place in the World Cup in the 200m K-2.

Azovmash Basketball Club, like the "Ilichevets" Water-polo Club, has numerous national championship titles. Significant successes were obtained as well by the Mariupol schools of boxing, Greco-Roman wrestling, artistic gymnastics, and other types of sport.

Sports building in the city (count 585):

- Volodymyr Boiko stadium

- Azovstal sports complex

- Azovets stadium (in the past known as Locomotive)

- Azovmash sports complex

- Sadko sports complex

- Vodnik sports complex

- Neptune public pool

- Azovstal chess club

Notable people

[edit]

- Mikhail Averbakh (1872–1944), Russian and Soviet ophthalmologist

- Dmitry Aynalov (1862–1939) a Soviet and Russian art historian and university professor

- Nikki Benz (born 1981), pornographic actress

- Vadym Boychenko (born 1977) Ukrainian politician, the Mayor of Mariupol

- Volodymyr Boyko (1938–2015), Ukrainian entrepreneur and politician

- Abram Budanov (1886–1929) a Ukrainian anarchist military commander

- Diana Hajiyeva (born 1989), singer who represented Azerbaijan at the Eurovision Song Contest 2017

- Konstantin Ivashchenko (born 1963) politician and businessman, de facto Mayor of Mariupol

- Felix Krivin (1928–2016) a Soviet, Ukrainian and Israeli poet, author and screenwriter.

- Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842–1910), a Ukrainian landscape painter of Pontic Greek descent.

- Leonid Lukov (1909–1963) a Soviet film director and screenwriter.

- Ivan Ivanovich Mavrov (1936–2009), physician

- Julie Pelipas (born 1984) a Ukrainian stylist and local fashion director of Vogue

- Vyacheslav Polozov (born 1950), opera singer and professor of voice

- Alexander Sakharoff (1886–1963), Russian Empire dancer, teacher and choreographer; emigrated to France.

- Olgierd Straszyński (1903–1971), Polish conductor.

- Mykola Trofymenko (born 1985), Ukrainian academic political scientist.

- Voron Viacheslav (born 1967), singer, composer and music producer

- Viacheslav Voron (born 1967), singer-songwriter of the Russian and Ukrainian chanson

- Sergey Voychenko (1955–2004), Belarusian artist and designer.[139]

- Alfred Wintle MC (1897–1966) a British military officer and one of London's great eccentrics.

- Oleksandr Yaroslavskyi (born 1959) a wealthy Ukrainian businessman.

- Anna Zatonskih (born 1978), Ukrainian American chess player

- Andrei Zhdanov (1896–1948), Soviet politician and cultural ideologist.

Sport

[edit]

- Sergei Baltacha, (born 1958), former 1988 European Football Championship runner-up

- Oleksandr Haydash (born 1967) former Ukrainian Russian football striker with 437 club caps.

- Oleh Kyryukhin (born 1975) a light flyweight boxer, bronze medallist at the 1996 Summer Olympics.

- Alexander Oleinik (born 1986) kickboxer and Muay Thai fighter

- Vyacheslav Oliynyk (born 1966) Ukrainian wrestler and gold medallist at the 1996 Summer Olympics

- Eduard Piskun (born 1967) is a Ukrainian former football player with over 450 club caps

- Viktor Prokopenko (1944–2007) a Ukrainian football player and coach

- Ihor Radivilov (born 1992), Olympic, world and European medalist in gymnastics

- Oleksandr Sydorenko (1960–2022), individual medley swimmer, gold medallist at the 1980 Summer Olympics

- Tetiana Ustiuzhanina (born 1965) competitive rower, team bronze medallist at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Oleksandr Volkov (born 1961) a former Soviet footballer with 515 club caps and Ukrainian football manager.

Sister cities

[edit]Before 2022

[edit]| City | Country | Since |

|---|---|---|

| Feodosia | 11 September 1993 | |

| Kherson | 11 September 1993 | |

| Lviv | 10 September 1994 | |

| Kolomyia[c] | 1 October 1998 | |

| Makiivka | 21 April 2000 | |

| Bakhchysarai | 17 February 2012 | |

| Slavuta | 28 July 2015 | |

| Pereiaslav | 27 March 2017 | |

| Savona | 30 September 1991 | |

| Santa Severina | 23 May 2005 | |

| Thessaloniki | 12 September 1993 | |

| Piraeus | 1993 | |

| Kalymnos[d] | 25 June 1998 | |

| Kythnos | 2 October 2010 | |

| Qiqihar | 12 October 2007 | |

| Trabzon[e] | 27 November 2007 | |

| Gdańsk | 12 December 2014[140] |

After 2022

[edit]After Russia set up an occupational administration in Mariupol, it was twinned with Saint-Petersburg on 24 May 2022[141] and Grozny on 10 August 2023. An art symbol of the twinning was unveiled on Palace Square in Saint Petersburg, which was later defaced and removed by unknown people.[142]

Notes

[edit]- ^ UK: /ˌmæriˈuːpɒl/ MARR-ee-OO-pol, US: /ˌmɑːriˈuːpəl/ ⓘ MAR-ee-OO-pəl; Ukrainian: Маріуполь [mɐr⁽ʲ⁾iˈupolʲ] ⓘ; Russian: Мариуполь, IPA: [mərʲɪˈupəlʲ]; Greek: Μαριούπολη, romanized: Marioúpoli

- ^ Russian: Здесь расстреляны жертвы фашистского геноцида – евреи Мариуполя. Октябрь 1941 года. Пусть их души будут связаны с живыми

- ^ The original cooperation agreement was lost as a result of a fire in the building of the Mariupol City Council

- ^ The original cooperation agreement was lost as a result of a fire in the building of the Mariupol City Council

- ^ The original cooperation agreement was lost as a result of a fire in the building of the Mariupol City Council

References

[edit]- ^ "CONSTITUTION OF UKRAINE". rm.coe.int. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d (in Ukrainian) Boychenko was re-elected mayor of Mariupol Archived 22 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (2 November 2020)

- ^ Konstantinova, Alla (31 January 2024). "Mapping the ruins. The reconstruction and demolition of occupied Mariupol". Mediazona.

- ^ a b c "Invaders develop 10-year plan for ethnic cleansing in Mariupol, replacing population with Russians – ISW". Interfax-Ukraine. 21 August 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "Mariupol". The Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ "Mariupol". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Богданьок, Олена (6 March 2022). "Харків, Чернігів, Маріуполь, Херсон, Гостомель і Волноваха тепер міста-герої". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine cedes control of Azovstal plant in Mariupol". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b Bulletin, American School of Prehistoric Research: The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Alseikaitė, American School of Prehistoric Research, p.46. Harvard University, 1956. Via Google Books, Pennsylvania State University

- ^ LeDonne John P. The territorial reform of the Russian Empire, 1775–1796 [II. The borderlands, 1777–1796]. In: Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. Vol. 24 No. 4. October–December 1983. p. 422.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R. "A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples," p. 197

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes," Journal of Contemporary History 1995 30: 265 "

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R. "A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples," p. 197.

- ^ a b N. D. Polons’ka –Vasylenko, "The Settlement of Southern Ukraine (1750–1775)," The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc., 1955, p. 16.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul R. 2010. "A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its People," University of Toronto Press. Second edition. P. 283.

- ^ LeDonne John P. The territorial reform of the Russian Empire, 1775–1796 [II. The borderlands, 1777–1796]. In: Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. Vol. 24 No. 4. October–December 1983. pp. 420–422.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes," Journal of Contemporary History 1995 30: 273

- ^ Gorbov V.N., Bozhko, R.P., Kushnir V.V. 2013. "Археологические комплексы на территории крепости Кальмиус и ее окрестностий," ("Archaeological complexes on the territory of the Kalmius fortress and its surroundings") Donetsk Archaeological Collection, No. 17, pp. 138–139, 141.

- ^ Clark, George B. "Irish Soldiers in Europe: 17th – 19th Century," Mercier Press, 12 October 2010. Pp. 272, 274, 276.

- ^ LeDonne John P. The territorial reform of the Russian Empire, 1775–1796 [II. The borderlands, 1777–1796]. In: Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. Vol. 24 No. 4. October–December 1983. p. 420-421

- ^ a b Section "Kalmius and the Kalmiusskaya Palanka" Archived 13 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, referencing A. A. Skalkowski, no citation.

- ^ Gorbov V.N., Bozhko, R.P., Kushnir V.V. 2013. "Археологические комплексы на территории крепости Кальмиус и ее окрестностий," ("Archaeological complexes on the territory of the Kalmius fortress and its surroundings") Donetsk Archaeological Collection, No. 17, p. 133

- ^ N. D. Polons’ka –Vasylenko, "The Settlement of Southern Ukraine (1750–1775)," The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc., 1955, p. 278

- ^ Mikhail Kizilov. "Slave Trade in the Early Modern Crimea From the Perspective of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources". Oxford University., p. 7 with n. 11

- ^ Reenactor.ru Archived 19 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine p. 521

- ^ Le Donne, John P. 1983. "The Territorial Reform of the Russian Empire », Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. Vol. 24, No. 4. Octobre-Décembre 1983. p. 419.

- ^ Posun’ko, Andriy, "After the Zaporizhzhia. Dissolution, reorganization, and transformation of borderland military in 1775–1835, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary, 2012, p. 35

- ^ Verenikin, V. Yet how old is our city? Vecherniy Mariupol Newspaper website.

- ^ Plotnikov, S. Mariupol icon of Theotokos "Hodegetria". Saint-Trinity Temple of Mariupol website. 9 August 2012

- ^ Dzhuvaha, V. One of the first deportation of the Empire. How Crimean Greeks populated Wild Fields. Ukrainska Pravda. 17 February 2011

- ^ Crimean Tatars (КРИМСЬКІ ТАТАРИ) Archived 25 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

- ^ "Victoria Konstantinova, Igor Lyman, Anastasiya Ignatova, European Vector of the Northern Azov in the Imperial Period: British Consular Reports about Italian Shipping (Berdiansk: Tkachuk O.V., 2016), 184 p." (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Igor Lyman, Victoria Konstantinova. German Consuls in the Northern Azov Region (Dnipro: LIRA, 2018), 500 p.

- ^ John P. McKay (1970). Pioneers for profit; foreign entrepreneurship and Russian industrialization, 1885–1913. University of Chicago Press. pp. 170, 230, 393. ISBN 9780226559926. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ It is a cultural property of a historical place indexed in the Ukrainian heritage register (Special Awards: Єврейська спадщина) under the reference 14-123-0029

- ^ a b c d e (Мариуполь еще не был занят, а уже было запланировано, что казни евреев в городе будут проведены зондеркомандой 10А, входившей в айнзацгруппу Д. Начальником команды был оберштурмбанфюрер Гейнц Зеетцен, даже среди офицеров карательных отрядов известный беспощадностью и жестокостью при исполнении особого приказа фюрера.история гибели евреев мариуполя. Мариуполь еще не был занят, а уже было запланировано, что казни евреев в городе будут проведены зондеркомандой 10А Archived 5 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b "Mariupol". Yad Vashem. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "More Mariupol residents died in Russian invasion than under Nazi occupation - mayor". 1 May 2022. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Шукач | Мемориальный комплекс "Менора" в с.Бердянское (Мангушский район)". www.shukach.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ https://heritage.toolforge.org/api/api.php?action=search&format=html&srcountry=ua&srlang=uk&srid=99-142-3901&props=image%7Cname%7Caddress%7Cmunicipalityd Archived 29 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine It is a cultural property of a historical place indexed in the Ukrainian heritage register (Special Awards: Єврейська спадщина) under the reference 99-142-3901.

- ^ "Мемориальный памятник "Менора" г. Мариуполь". ujew.com.ua.

- ^ " Мемориальный памятник "Менора" г. Мариуполь ". Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Remembrance of Culture: Mariupol Synagogue". Mariupol Future. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 90, 96, 103, 106, 373. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "Mariupol". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Blair, David (10 May 2014). "Ukraine: Security forces abandon Mariupol ahead of referendum". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Vasovic, Aleksandar (13 June 2014). "Ukrainian forces reclaim port city from rebels". Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "The President instructed the Head of the Donetsk Regional State Administration to relocate temporarily the administration office to Mariupol". president.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Russia opens 3rd front with a new offensive: Ukrainian, Western officials". CNBC. 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Weapons Aren't Smart for Ukraine". Bloomberg. 21 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "Rockets fired on Ukraine's Mariupol from rebel territory: OSCE". Yahoo News. 24 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Shyrokyne: Ruined front-line village and people who still hope to return home". 2019. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (24 January 2015). "Ukraine crisis: dozens die as rebels shell Mariupol". Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Full Report: Russian Officers and Militants Identified as Perpetrators of the January 2015 Mariupol Artillery Strike". 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian forces launch offensive near Mariupol, east Ukraine: Kiev". Reuters. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Rebels withdraw from key frontline village: Kiev". Daily Star. Agence France-Presse. 3 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Fisher, Jonah (27 November 2018). "Why Ukraine-Russia sea clash is fraught with risk". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Putin's bridge over troubled waters Archived 19 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail (26 October 2018)

- ^ "The Azov Sea, symbolic prize of Russia-Ukraine war". France 24. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Vasovic, Aleksandar (24 February 2022). "Port city of Mariupol comes under fire after Russia invades Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Timeline: Russia's siege of Ukraine's Mariupol". 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "Live updates: Zelenskyy vows to keep negotiating with Russia. The latest developments on the Russia-Ukraine war: (Section titled "Geneva" NOTE there are two sections with the same name— "Geneva" SEE THE FIRST)". Apneas.com. Associated Press. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: ICRC calls for urgent solution to save lives and prevent worst-case scenario in Mariupol". International Committee of the Red Cross. 13 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Aid workers describe 'apocalyptic' scenes in Mariupol, a Ukrainian city under siege". news.yahoo.com. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Putin's Mariupol Massacre is one of the 21st century's worst war crimes". Atlantic Council. 25 May 2022. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Sandford, Alasdair (10 March 2022). "More than 1.9 million internally displaced in Ukraine, says UN". euronews. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Sangal, Aditi; Vogt, Adrienne; Wagner, Meg; Ramsay, George; Guy, Jack; Regan, Helen (10 March 2022). "Russian forces bombed a maternity and children's hospital. Here's what we know about the siege of Mariupol". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

Police in the Donetsk region said according to preliminary information at least 17 people were injured, including mothers and staff. Ukraine's President said authorities were sifting through the rubble looking for victims.

- ^ "Ukraine: Mariupol Theater Hit by Russian Attack Sheltered Hundreds". Human Rights Watch. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Engelbrecht, Cora; Kramer, Andrew E. (19 April 2022). "Despair in Mariupol's last stronghold: 'They're bombing us with everything'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Hopkins, Valerie; Nechepurenko, Ivan; Santora, Marc (16 May 2022). "The Ukrainian authorities declare an end to the combat mission in Mariupol after weeks of Russian siege". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- "Hundreds of Ukrainian troops evacuated from Mariupol steelworks after 82-day assault". The Guardian. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Минобороны показало кадры сдачи в плен украинских военных с "Азовстали"". РБК (in Russian). 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- "UPDATE 3-Azovstal siege ends as hundreds of Ukrainian fighters surrender – Reuters witness". finance.yahoo.com. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- "Fate of hundreds of Ukrainian fighters uncertain after surrender". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Krever, Mick (17 June 2022). "UN says more than 1,300 civilians killed in Mariupol — but true toll "likely thousands higher"". Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Patel-Carstairs, Sunita (18 March 2022). "Ukraine war: Videos show apocalyptic destruction in Mariupol as Russia says it is 'tightening its encirclement'". Sky News. Sky New. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022. }

- ^ "High Commissioner updates the Human Rights Council on Mariupol, Ukraine". OHCHR. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ Regan, Helen; Khalil, Hafsa; Guy, Jack; Upright, Ed; Hammond, Elise; Vogt, Adrienne; Sangal, Aditi (17 June 2022). "UN says more than 1,300 civilians killed in Mariupol — but true toll "likely thousands higher"". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "UN says more than 1,300 civilians killed in Mariupol — but true toll "likely thousands higher"". 17 June 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "The agony of not knowing, as Mariupol mass burial sites grow". British Broadcasting Corporation. 7 November 2022. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Ledwidge, Frank (23 November 2022). "Ukraine war: after recapture of Kherson the conflict is poised at the gates of Crimea". Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "Russia scrubs Mariupol's Ukrainian identity, builds on death". AP News. 23 December 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Lori Hinnant (23 December 2022). "'Everything is black, is destroyed': Russia erases Mariupol's Ukrainian identity". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.