Milton Keynes

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 51 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 51 min

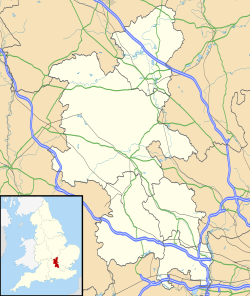

| Milton Keynes | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Area | 89 km2 (34 sq mi) [1] |

| Founded | 23 January 1967[a][1] |

| OS grid reference | SP841386 |

| • London | 50 mi (80 km)[b] SSE |

| District | |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MILTON KEYNES |

| Postcode district | MK1–15, MK17, MK19 |

| Dialling code | 01908 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | milton-keynes |

Milton Keynes (/kiːnz/ ⓘ KEENZ) is a city[c] in Buckinghamshire, England, about 50 miles (80 km) north-west of London.[b] At the 2021 Census, the population of its urban area was 264,349. The River Great Ouse forms the northern boundary of the urban area; a tributary, the River Ouzel, meanders through its linear parks and balancing lakes. Approximately 25% of the urban area is parkland or woodland and includes two Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). The city is made up of many different districts.

In the 1960s, the government decided that a further generation of new towns in the south east of England was needed to relieve housing congestion in London. Milton Keynes was to be the biggest yet, with a population of 250,000 and area of 22,000 acres (9,000 ha). At designation, its area incorporated the existing towns of Bletchley, Fenny Stratford, Wolverton and Stony Stratford,[d] along with another fifteen villages and farmland in between. These settlements had an extensive historical record since the Norman conquest; detailed archaeological investigations before development revealed evidence of human occupation from the Neolithic period, including the Milton Keynes Hoard of Bronze Age gold jewellery. The government established Milton Keynes Development Corporation (MKDC) to design and deliver this new city. The Corporation decided on a softer, more human-scaled landscape than in the earlier English new towns but with an emphatically modernist architecture. Recognising how traditional towns and cities had become choked in traffic, they established a grid of distributor roads about 1 km (0.6 mi) between edges, leaving the spaces between to develop more organically. An extensive network of shared paths for leisure cyclists and pedestrians criss-crosses through and between them. Rejecting the residential tower block concept that had become unpopular, they set a height limit of three storeys outside Central Milton Keynes.

Facilities include a 1,400-seat theatre, a municipal art gallery, two multiplex cinemas, an ecumenical central church, a 400-seat concert hall, a teaching hospital, a 30,500-seat football stadium, an indoor ski-slope and a 65,000-capacity open-air concert venue. Seven railway stations serve the Milton Keynes urban area (one inter-city). The Open University is based here and there is a small campus of the University of Bedfordshire. Most major sports are represented at amateur level; Red Bull Racing (Formula One), MK Dons (association football), and Milton Keynes Lightning (ice hockey) are its professional teams. The Peace Pagoda overlooking Willen Lake was the first such to be built in Europe. The many works of sculpture in parks and public spaces include the iconic Concrete Cows at Milton Keynes Museum.

Milton Keynes is among the most economically productive localities in the UK, ranking highly against a number of criteria. It has the UK's fifth-highest number of business startups per capita (but equally of business failures). It is home to several major national and international companies. Despite economic success and personal wealth for some, there are pockets of nationally significant poverty. The employment profile is composed of about 90% service industries and 9% manufacturing.

History

[edit]Birth of a 'new city'

[edit]It may startle some political economists to talk of commencing the building of new cities ... planned as cities from their first foundation, and not mere small towns and villages. ... A time will arrive when something of this sort must be done ... England cannot escape from the alternative of new city building.

In the 1960s, the UK government decided that a further generation of new towns in the South East of England was needed to relieve housing congestion in London.[10] Since the 1950s, overspill housing for several London boroughs had been constructed in Bletchley.[11][12][13] Further studies[10][14] in the 1960s identified north Buckinghamshire as a possible site for a large new town, a new city,[15][e] encompassing the existing towns of Bletchley, Stony Stratford, and Wolverton.[16] The New Town (informally and in planning documents, 'New City') was to be the biggest yet, with a target population of 250,000,[17][18] in a 'designated area' of 21,883 acres (8,855.7 ha).[1] The name 'Milton Keynes' was taken from that of an existing village on the site.[19]

On 23 January 1967, when the formal "new town designation order" was made,[1] the area to be developed was largely farmland and undeveloped villages. The site was deliberately located equidistant from London, Birmingham, Leicester, Oxford, and Cambridge,[20][21] with the intention that it would be self-sustaining and eventually become a major regional centre in its own right.[10] Planning control was taken from elected local authorities and delegated to the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (MKDC). Before construction began, every area was subject to detailed archaeological investigation: doing so has exposed a rich history of human settlement since Neolithic times and has provided a unique insight into the history of a large sample of the landscape of North Buckinghamshire.[22]

The corporation's strongly modernist designs were regularly featured in the magazines Architectural Design and the Architects' Journal.[23][24][25] MKDC was determined to learn from the mistakes made in the earlier new towns,[26][27] and revisit the garden city ideals.[28][29] They set in place the characteristic grid roads that run between districts ('grid squares'), as well as a programme of intensive planting, balancing lakes and parkland.[30] Central Milton Keynes ("CMK") was not intended to be a traditional town centre but a central business and shopping district to supplement local centres embedded in most of the grid squares.[31] This non-hierarchical devolved city plan was a departure from the English new towns tradition and envisaged a wide range of industry and diversity of housing styles and tenures.[32] The largest and almost the last of the British New Towns, Milton Keynes has 'stood the test of time far better than most, and has proved flexible and adaptable'.[33] The radical grid plan was inspired by the work of Melvin M. Webber,[34] described by the founding architect of Milton Keynes, Derek Walker, as the 'father of the city'.[35] Webber thought that telecommunications meant that the old idea of a city as a concentric cluster was out of date and that cities which enabled people to travel around them readily would be the thing of the future, achieving "community without propinquity" for residents.[36]

The government wound up MKDC in 1992, 25 years after the new town was founded. Control was transferred to the Commission for New Towns (CNT) and then finally to English Partnerships, with planning functions returning to the local council (Milton Keynes Borough (now City) Council). From 2004 to 2011 a government quango, the Milton Keynes Partnership, had development control powers to accelerate the growth of Milton Keynes.[37]

Formal award of city status

[edit]Along with many other towns and boroughs, Milton Keynes competed (unsuccessfully) for formal city status in the 2000, 2002 and 2012 competitions.[38] However the Borough (including rural areas, in addition to the MK urban area[39]) was successful in 2022, in the Queen's Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours competition. On 15 August 2022, the Crown Office announced formally that Queen Elizabeth II had ordained by letters patent that the Borough of Milton Keynes has been given city status.[40] In law, it is the Borough rather than its eponymous settlement that has city status; nevertheless it is the latter that is more commonly known as the city.[41][42]

Name

[edit]Labour Minister Dick Crossman ... looked at [a] map and saw [the] name and said "Milton the poet, Keynes the economic one. 'Planning with economic sense and idealism, a very good name for it.'"

The name 'Milton Keynes' was a reuse of the name of one of the original historic villages in the designated area,[43] now more generally known as 'Milton Keynes Village' to distinguish it from the modern settlement. After the Norman conquest, the de Cahaignes family held the manor from 1166 to the late 13th century as well as others in the country (Ashton Keynes in Wiltshire, Somerford Keynes in Gloucestershire, and Horsted Keynes in West Sussex).[44] The village was originally known as Middeltone (11th century); then later as Middelton Kaynes or Caynes (13th century); Milton Keynes (15th century); and Milton alias Middelton Gaynes (17th century).[44]

Prior history

[edit]

The area that was to become Milton Keynes encompassed a landscape that has a rich historic legacy. The area to be developed was largely farmland and undeveloped villages, but with evidence of permanent settlement dating back to the Bronze Age. Before construction began, every area was subject to detailed archaeological investigation: this work has provided an insight into the history of a very large sample of the landscape of south-central England. There is evidence of Stone Age,[45] late Bronze Age/early Iron Age,[46] Romano-British,[47][48] Anglo-Saxon,[49] Anglo-Norman,[50] Medieval,[51][49] and late Industrial Revolution settlements such as the railway towns of Wolverton (with its railway works) and Bletchley (at the junction of the London and North Western Railway with the Oxford–Cambridge Varsity Line).[52][53] The most notable archaeological artefact was the Milton Keynes Hoard, which the British Museum described as 'one of the biggest concentrations of Bronze Age gold known from Britain and seems to flaunt wealth.'[54]

Bletchley Park, the site of World War II Allied code-breaking and Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic digital computer,[55] is a major component of MK's modern history. It is now a flourishing heritage attraction, receiving hundreds of thousands of visitors annually.[56]

When the boundary of Milton Keynes was defined in 1967, some 40,000 people lived in four towns and fifteen villages or hamlets in the "designated area".[57][58]

Geography

[edit]Location and nearest settlements

[edit]Milton Keynes is in south central England, at the northern end of the South East England region,[59] about 50 miles (80 km) north-west of London.[2][3][4]

The nearest larger[f] towns are Northampton, Bedford, Luton and Aylesbury.[60] The nearest larger[g] cities are Coventry, Leicester, Cambridge, London and Oxford.[61]

Geology

[edit]Its surface geology is primarily gently rolling Oxford clay or, more formally:

... a portion of more or less dissected boulder clay plateau, with streams falling fairly steeply to the [Great] Ouse and Ouzel flood plains, across slopes cut chiefly in Oxford clay. Middle Jurassic rocks, in particular the Blisworth limestone and cornbrash, form strong features in the lands bordering the Ouse valley in the north.[62]

Its highest points are in the centre (110 m; 360 ft) and at Woodhill on the western boundary (120 m; 390 ft).[63][64] The lowest point of the urban area is in Newport Pagnell, where the Ouzel joins the Great Ouse (50 m; 160 ft).[65]

Parks and environmental infrastructure

[edit]Because of the (poorly drained) clay soils and the urban hard surfaces, the development corporation identified water runoff into the Ouzel and its tributaries as a significant risk to be managed and so put in place two large balancing lakes (Caldecotte and Willen) and a number of smaller detention ponds.[66] These provide an important leisure amenity for most of the year.[67] Building in the floodplains of the Ouse and Ouzel was precluded too, thus providing long-distance linear parks that are within easy reach of most residents.

The north basin of Willen Lake is a bird sanctuary,[68] with a Peace Pagoda and Buddhist temple by the lake.

The two Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Howe Park Wood and Oxley Mead, are the most significant of a number of important wildlife sites in and around MK.[69]

Just outside the Milton Keynes urban area lies Little Linford Wood, a conservation site and nature reserve managed by the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust. It is considered to be one of the best habitats for dormice.[70]

Climate

[edit]Milton Keynes experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) as is typical of almost all of the United Kingdom.

The nearest Met Office weather station is in Woburn, Bedfordshire,[71] just outside the south eastern fringe of Milton Keynes.[h] Recorded temperature extremes range from 39.6 °C (103.3 °F) during July 2022,[72] to as low as −20.6 °C (−5.1 °F) on 25 February 1947; this is the lowest temperature ever reported in England in February.[73] On 20 December 2010, the temperature fell to −16.3 °C (2.7 °F)[74]

| Climate data for Woburn,[i] (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1898–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.0 (−4.0) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.4 (2.18) |

44.6 (1.76) |

39.6 (1.56) |

48.3 (1.90) |

51.9 (2.04) |

54.2 (2.13) |

51.2 (2.02) |

58.6 (2.31) |

55.4 (2.18) |

70.7 (2.78) |

64.5 (2.54) |

58.2 (2.29) |

655.3 (25.80) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.7 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 11.0 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 119.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 53.0 | 72.3 | 114.9 | 152.2 | 191.5 | 185.7 | 198.4 | 185.3 | 141.6 | 104.5 | 62.0 | 48.3 | 1,509.4 |

| Source 1: Met Office[75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[76] | |||||||||||||

Urban design

[edit]The radical plan, form and scale of Milton Keynes attracted international attention.[27] Early phases of development include work by celebrated architects, including Sir Richard MacCormac,[77] Norman Foster,[78] Henning Larsen,[79] Ralph Erskine,[80] John Winter,[81] and Martin Richardson.[33] Led by Lord Campbell of Eskan (chairman) and Fred Roche (General Manager), the Corporation attracted talented young architects,[82] led by the respected designer,[82][83] Derek Walker. In the modernist Miesian tradition is the Shopping Building designed by Stuart Mosscrop and Christopher Woodward, a grade II listed building, which the Twentieth Century Society inter alia regards as the 'most distinguished' twentieth century retail building in Britain.[84][85] The Development Corporation also led an ambitious public art programme.[86]

The urban design has not been universally praised. In 1980, the then president of the Royal Town Planning Institute, Francis Tibbalds, described Central Milton Keynes as "bland, rigid, sterile, and totally boring."[87] Michael Edwards, a member of the original consultancy team,[j] believes that there were weaknesses in their proposal and that the Development Corporation implemented it badly.[88]

Grid roads and grid squares

[edit]The geography of Milton Keynes – the railway line, Watling Street, Grand Union Canal, M1 motorway – sets up a very strong north-south axis. If you've got to build a city between (them), it is very natural to take a pen and draw the rungs of a ladder. Ten miles by six is the size of this city – 22,000 acres. Do you lay it out like an American city, rigid orthogonal from side to side? Being more sensitive in 1966–7, the designers decided that the grid concept should apply but should be a lazy grid following the flow of land, its valleys, its ebbs and flows. That would be nicer to look at, more economical and efficient to build, and would sit more beautifully as a landscape intervention.

The Milton Keynes Development Corporation planned the major road layout according to street hierarchy principles, using a grid pattern of approximately 1 km (0.6 mi) intervals, rather than on the more conventional radial pattern found in older settlements.[90] Major distributor roads run between communities, rather than through them: these distributor roads are known locally as grid roads and the spaces between them – the neighbourhoods – are known as grid squares (though few are actually square or even rectilinear).[91] This spacing was chosen so that people would always be within six minutes' walking distance of a grid-road bus-stop.[31][k] Consequently, each grid square is a semi-autonomous community, making a unique collective of 100 clearly identifiable neighbourhoods within the overall urban environment.[92][l] The grid squares have a variety of development styles, ranging from conventional urban development and industrial parks to original rural and modern urban and suburban developments. Most grid squares have a local centre, intended as a retail hub, and many have community facilities as well. Each of the original villages is the heart of its own grid-square. Originally intended under the master plan to sit alongside the grid roads,[94] these local centres were mostly in fact built embedded in the communities.[95][88]

Although the 1970 master plan assumed cross-road junctions,[94] roundabout junctions were built at intersections because this type of junction is more efficient at dealing with small to medium volumes. Some major roads are dual carriageway, the others are single carriageway. Along one side of each single carriageway grid road, there is usually a (grassed) reservation to permit dualling or additional transport infrastructure at a later date.[m] As of 2018[update], this has been limited to some dualling. The edges of each grid square are landscaped and densely planted – some additionally have noise attenuation mounds – to minimise traffic noise from the grid road impacting the adjacent grid square. Traffic movements are fast, with relatively little congestion since there are alternative routes to any particular destination other than during peak periods. The national speed limit applies on the grid roads, although lower speed limits have been introduced on some stretches to reduce accident rates. Pedestrians rarely need to cross grid roads at grade, as underpasses and bridges were specified at frequent places along each stretch of all of the grid roads.[94] In contrast, the later districts planned by English Partnerships have departed from this model, without a road hierarchy but with conventional junctions with traffic lights and at grade pedestrian crossings.[27][97][n]

Redways

[edit]

There is a separate network (approximately 170 miles (270 km) total length) of cycle and pedestrian routes – the redways – that runs through the grid-squares and often runs alongside the grid-road network.[98] This was designed to segregate slow moving cycle and pedestrian traffic from fast moving motor traffic.[93] In practice, it is mainly used for leisure cycling rather than commuting, perhaps because the cycle routes are shared with pedestrians, cross the grid-roads via bridge or underpass rather than at grade, and because some take meandering scenic routes rather than straight lines. It is so called because it is generally surfaced with red tarmac.[99] The national Sustrans national cycle network routes 6 and 51 take advantage of this system.[100][101]

Height

[edit]

The original design guidance declared that commercial building heights in the centre should not exceed six storeys, with a limit of three storeys for houses (elsewhere),[23] paraphrased locally as "no building taller than the tallest tree".[103] In contrast, the Milton Keynes Partnership, in its expansion plans for Milton Keynes, believed that Central Milton Keynes (and elsewhere) needed "landmark buildings" and subsequently lifted the height restriction for the area.[103] As a result, high rise buildings have been built in the central business district.[o] As of 2014, local plans have protected the existing boulevard framework and set higher standards for architectural excellence.[107][p]

Linear parks

[edit]

The flood plains of the Great Ouse and of its tributaries (the Ouzel and some brooks) have been protected as linear parks that run right through Milton Keynes; these were identified as important landscape and flood-management assets from the outset.[110] At 4,100 acres (1,650 ha) – ten times larger than London's Hyde Park and a third larger than Richmond Park[111] – the landscape architects realised that the Royal Parks model would not be appropriate or affordable and drew on their National Park experience.[111] As Bendixson and Platt (1992) write: "They divided the Ouzel Valley into 'strings, beads and settings'. The 'strings' are well-maintained routes, be they for walking, bicycling or riding; the 'beads' are sports centres, lakeside cafes and other activity areas; the 'settings' are self-managed land-uses such as woods, riding paddocks, a golf course and a farm".[111]

The Grand Union Canal is another green route (and demonstrates the level geography of the area – there is just one minor lock in its entire 10-mile (16 km) meandering route through from the southern boundary near Fenny Stratford to the "Iron Trunk" aqueduct over the Ouse at Wolverton at its northern boundary).

The initial park system was planned by Peter Youngman (Chief Landscape Architect),[112] who also developed landscape precepts for all development areas: groups of grid squares were to be planted with different selections of trees and shrubs to give them distinct identities. The detailed planning and landscape design of parks and of the grid roads was evolved under the leadership of Neil Higson,[113] who from 1977 took over from Youngman.[114]

In a national comparison of urban areas by open space available to residents, Milton Keynes ranked highest in the UK.[115] Milton Keynes is unusual in that most of the parks are owned and managed by a charity, the Milton Keynes Parks Trust rather than the local authority, to ensure that the management of the city's green spaces is largely independent of the council's expenditure priorities.[116]

Forest city concept

[edit]The Development Corporation's original design concept aimed for a "forest city" and its foresters planted millions of trees from its own nursery in Newlands in the following years.[35] Parks, lakes and green spaces cover about 25% of Milton Keynes;[117][118] as of 2018[update], there are 22 million trees and shrubs in public open spaces.[119][118] When the Development Corporation was being wound up, it transferred the major parks, lakes, river-banks and grid-road margins to the Parks Trust,[120] a charity which is independent of the municipal authority.[117] MKDC endowed the Parks Trust with a portfolio of commercial properties, the income from which pays for the upkeep of the green spaces.[117] As of 2018[update], approximately 25% of the urban area is parkland or woodland.[121] It includes two Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Howe Park Wood and Oxley Mead.

Centre

[edit]As a key element of the planners' vision,[122] Milton Keynes has a purpose built centre, with a very large "covered high street" shopping centre,[123] a theatre,[124][125] municipal art gallery,[124][125] a multiplex cinema,[126] hotels,[127] central business district,[122] an ecumenical church,[128] Milton Keynes Civic Offices[129] and central railway station.[130]

Campbell Park, a formal park extending east from the business area to the Grand Union Canal, is described in the Pevsner Architectural Guides as "...the largest and most imaginative park to have been laid out in Britain in the 20th century".[114] The park is listed (grade 2) by Historic England,[131]

Original towns and villages

[edit]

Milton Keynes consists of many pre-existing towns and villages that anchored the urban design,[16] as well as new infill developments. The modern-day urban area outside the original six towns (Bletchley, Fenny Stratford, Newport Pagnell,[q] Stony Stratford, Wolverton, and Woburn Sands[q]) was largely rural farmland but included many picturesque North Buckinghamshire villages and hamlets: Bradwell village and its Abbey, Broughton, Caldecotte, Great Linford, Loughton, Milton Keynes Village, New Bradwell, Shenley Brook End, Shenley Church End, Simpson, Stantonbury, Tattenhoe, Tongwell, Walton, Water Eaton, Wavendon, Willen, Great and Little Woolstone, Woughton on the Green.[16] These historical settlements were made the focal points of their respective grid square. Every other district has an historical antecedent, if only in original farms or even field names.[132]

Bletchley was first recorded in the 12th century as Blechelai. Its station was an important junction (the London and North Western Railway with the Oxford-Cambridge Varsity Line), leading to the substantial urban growth in the town in the Victorian period. It expanded to absorb the village of Water Eaton and town of Fenny Stratford.[52]

Bradwell is a traditional rural village with earthworks of a Norman motte and bailey and parish church.[133] Bradwell Abbey, a former Benedictine Priory and scheduled monument,[134] was of major economic importance in this area of North Buckinghamshire before its dissolution in 1524.[135] Nowadays there is only a small medieval chapel and a manor house occupying the site.[136][137] New Bradwell, to the north of Bradwell and east of Wolverton, was built specifically for railway workers.[133] The level bed of the old Wolverton to Newport Pagnell Line near here has been converted to a redway, making it a favoured route for cycling.[138] A working windmill is sited on a hill outside the village.[139]

Great Linford appears in the Domesday Book as Linforde, and features a church dedicated to Saint Andrew, dating from 1215.[140] Today, the outer buildings of the 17th century manor house form an arts centre.[141]

Milton Keynes (Village) is the original village to which the New Town owes its name.[19] The original village is still evident, with a thatched pub, village hall, church and traditional housing. The area around the village has reverted to its 11th century name of Middleton (Middeltone).[142] The oldest surviving domestic building in the area (c. 1300 CE), "perhaps the manor house", is here.[143]

Stony Stratford began as a settlement on Watling Street during the Roman occupation, beside the ford over the Great Ouse. There has been a market here since 1194 (by charter of King Richard I).[144] The former Rose and Crown Inn on the High Street is reputedly the last place the Princes in the Tower were seen alive.[145]

The manor house of Walton village, Walton Hall, is the headquarters of the Open University and the tiny parish church (deconsecrated) is in its grounds.[146] The small parish church (1680) at Willen was designed by the architect and physicist Robert Hooke.[147][148] Nearby, by Willen Lake, there is a Buddhist Temple and the Peace Pagoda, which was built in 1980 and was the first built by the Nipponzan-Myōhōji Buddhist Order in the western world.[149]

The original Wolverton was a medieval settlement just north and west of today's town. The ridge and furrow pattern of agriculture can still be seen in the nearby fields.[150] The 12th century (rebuilt in 1819) Church of the Holy Trinity still stands next to the Norman motte and bailey site. Modern Wolverton was a 19th-century New Town built to house the workers at the Wolverton railway works, which built engines and carriages for the London and North Western Railway.[53]

Among the smaller villages and hamlets are three – Broughton, Loughton and Woughton on the Green – that are of note in that their names each use a different pronunciation[r] of the ough letter sequence in English.[151][152]

Education

[edit]Schools

[edit]In early planning, education provision was carefully integrated into the development plans with the intention that school journeys would, as far as possible, be made by walking and cycling. Each residential grid square was provided with a primary school (ages 5 to 8) for c. 240 children, and for each two squares there was a middle school (ages 8 to 12) for c.480 children. For each eight squares there was a large secondary education campus, to contain between two and four schools for a total of 3,000–4,500 children. A central resource area served all the schools on a campus. In addition, each campus included a leisure centre with indoor and outdoor sports facilities and a swimming pool, plus a theatre. These facilities were available to the public outside school hours, thus maximising use of the investment.[153] Changes in central government policy from the 1980s onwards subsequently led to much of this system being abandoned. Some schools have since been merged and sites sold for development, many converted to academies, and the leisure centres outsourced to commercial providers.

As in most parts of the UK, the state secondary schools in Milton Keynes are comprehensives,[154] although schools in the rest of Buckinghamshire still use the tripartite system.[155] Private schools are also available.[156]

Universities and colleges

[edit]The Open University's headquarters are in the Walton Hall district; though because this is a distance learning institution, the only students resident on campus are approximately 200 full-time postgraduates. Cranfield University, an all-postgraduate institution, is in nearby Cranfield, Bedfordshire. Milton Keynes College provides further education up to foundation degree level. A campus of the University of Bedfordshire provides some tertiary education facilities locally.

As of 2023[update], Milton Keynes is the UK's largest population centre without its own conventional university, a shortfall that the Council aims to rectify.[157] In January 2019, the council and its partner, Cranfield University, invited proposals to design a campus near the Central station for a new university, code-named MK:U.[158] However this project seems unlikely to proceed, following a government decision in January 2023 to deny funding.[159] In June 2023, the Open University announced that it would "initiate work on the strategic and financial case to relocate [from] the OU's existing campus at Walton Hall to a new site adjacent to the central railway station" and possibly commence teaching full-time undergraduates.[160]

Through Milton Keynes University Hospital, the city also has links with the University of Buckingham's medical school.

City development archive and library

[edit]Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre at Bradwell Abbey holds an extensive archive about the planning and development of Milton Keynes and has an associated research library.[161] The centre also offers an education programme (with a focus on urban geography and local history) to schools, universities and professionals.[161]

Culture, media and sport

[edit]Music

[edit]

The open-air National Bowl is a 65,000-capacity venue for large-scale events.[162]

In Wavendon, the Stables – founded by the jazz musicians Cleo Laine and John Dankworth – provides a venue for jazz, blues, folk, rock, classical, pop and world music.[163] It presents around 400 concerts and over 200 educational events each year and also hosts the National Youth Music Camps summer camp for young musicians.[164] In 2010, the Stables founded the biennial IF Milton Keynes International Festival, producing events in unconventional spaces and places across Milton Keynes.[165]

Milton Keynes City Orchestra is a professional freelance orchestra based at Woughton Campus.[166]

Arts, cinema, theatre and museums

[edit]The municipal public art gallery, MK Gallery, presents exhibitions of international contemporary art.[167] The gallery was extended and remodelled in 2018/19 and includes an art-house cinema.[168][169][170] Elsewhere in the city, there are two multiplex cinemas; one in CMK and one in Denbigh.

In 1999, the adjacent 1,400-seat Milton Keynes Theatre opened.[171] The theatre has an unusual feature: the ceiling can be lowered closing off the third tier (gallery) to create a more intimate space for smaller-scale productions.[171][172] There is a further professional performance space in Stantonbury.[173]

There are three museums: the Bletchley Park complex, which houses the museum of wartime cryptography;[174] the National Museum of Computing (adjacent to Bletchley Park, with a separate entrance), which includes a working replica of the Colossus computer;[175] and the Milton Keynes Museum, which includes the Stacey Hill Collection of rural life that existed before the foundation of MK, the British Telecom collection, and the original Concrete Cows.[176] Other numerous public sculptures in Milton Keynes include work by Elisabeth Frink, Philip Jackson, Nicolas Moreton and Ronald Rae.[177]

Milton Keynes Arts Centre offers a year-round exhibition programme, family workshops and courses. The centre is based in some of Linford Manor's historical exterior buildings, barns, almshouses and pavilions.[141] The Westbury Arts Centre in Shenley Wood is based in a 16th-century grade II listed farmhouse building. Westbury Arts has been providing spaces and studios for professional artists since 1994.[178]

Communications and media

[edit]For television, the city is allocated to BBC East and ITV Anglia.[179][s] For radio, Milton Keynes is served by Heart East (a regional commercial station based locally) and two community radio stations (MKFM and 1055 The Point).[181] BBC Three Counties Radio is the local BBC Radio station.[citation needed] CRMK (Cable Radio Milton Keynes) is a voluntary station broadcasting on the Internet.[182]

As of September 2021[update], Milton Keynes has one local newspaper, the Milton Keynes Citizen,[183][t] which has a significant online presence.

Sport

[edit]

Milton Keynes has professional teams in football (Milton Keynes Dons F.C. at Stadium MK), in ice hockey (Milton Keynes Lightning at Planet Ice Milton Keynes), and in Formula One (Red Bull Racing).[185]

The Xscape indoor ski slope and the iFLY indoor sky diving facility are important attractions in CMK;[185] the National Badminton Centre in Loughton is home to the national badminton squad and headquarters of Badminton England.[185][186]

Many other sports are represented at amateur level.

Near the central station, in a space beside the former Milton Keynes central bus station, there is a purpose-built street skateboarding plaza named the Buszy.[187]

Willen Lake hosts watersports on the south basin.[68][188]

New technologies

[edit]In recent years, the City Council has promoted MK as a test-bed for experimental urban technologies. The most well-known of these is the Starship Technologies' (largely) autonomous delivery robots: Milton Keynes provided its world-first urban deployment of these units in 2018.[189] By October 2020, said Starship, Milton Keynes had the 'world's largest autonomous robot fleet'.[190] Other projects include the LUTZ Pathfinder pod, an autonomous (self-driving) vehicle built by the Transport Systems Catapult.

Government

[edit]Local government

[edit]The responsible local government is Milton Keynes City Council, which administers the City of Milton Keynes, a unitary authority, and non-metropolitan county in law, since May 1996.[191] Until then, it was controlled by Buckinghamshire County Council. Historically, most of the area that became Milton Keynes was known as the "Three Hundreds of Newport".[192]

The unitary authority area, which extends beyond the ONS-defined Milton Keynes built-up area and encompasses the town of Olney and many rural villages and hamlets, is fully parished.[193]

International co-operation

[edit]Although Milton Keynes has no formalised twinning agreements, it has partnered and co-operated with various cities over the years. The most contact has been with Almere, Netherlands, especially on energy management and urban planning.[194] For several years from 1995, the city co-operated with Tychy, Poland,[195][196] after participating in the European City Cooperation System in Tychy in March 1994.[197]

Due to the twinning of the borough and the equivalent administrative region of Bernkastel-Wittlich, the council worked with Bernkastel-Kues, Germany, for example on art projects.[198]

In 2017 they partnered with the Chinese fellow smart city of Yinchuan.[199]

Infrastructure

[edit]Hospitals

[edit]Milton Keynes University Hospital, in the Eaglestone district, is an NHS general hospital with an Accident and Emergency unit.[200] It is associated for medical teaching purposes with the University of Buckingham medical school.[201] There are two small private hospitals: BMI Healthcare's Saxon Clinic and Ramsay Health Care's Blakelands Hospital.[202][203]

Prison

[edit]There is a Category A male prison, HMP Woodhill, on the western boundary.[204] A section of the prison is a Young Offenders Institution.[205]

Transport

[edit]

The Grand Union Canal, the West Coast Main Line, the A5 road and the M1 motorway provide the major axes that influenced the urban designers.[110]

The urban area is served by seven railway stations.[206] Wolverton, Milton Keynes Central and Bletchley stations are on the West Coast Main Line and are served by local commuter services between London and Birmingham or Crewe.[207] Milton Keynes Central is also served by inter-city services between London and Scotland, Wales and the North West and the West Midlands of England; express services to London take 35 minutes.[207] Bletchley, Fenny Stratford, Bow Brickhill, Woburn Sands and Aspley Guise railway stations are on the Marston Vale line to Bedford.[207]

The M1 motorway runs along the east flank of MK and serves it from junctions 13 and 14 within the environs of the city, and junctions 11a and 15 slightly further away via other connecting roads. The A5 road, designated as a trunk road, runs right through the west of the city centre, as a grade separated dual carriageway. Other main roads are the A509 to Wellingborough and Kettering, and the A421 and A422, both running west towards Buckingham (and Oxford) and east towards Bedford (and Cambridge). Additionally, the A4146 runs from (near) junction 14 of the M1 to Leighton Buzzard.[208] Proximity to the M1 has led to construction of a number of distribution centres, including Magna Park at the south-eastern flank of Milton Keynes, near Wavendon and M1 J13.[209]

Many long-distance coaches stop at the Milton Keynes Coachway,[210] (beside M1 Junction 14), about 3.3 miles (5.3 km) from the centre and 4.3 mi (7 km) from Milton Keynes Central railway station.[211] There is also a park and ride car park on the site.

The city is also served by a number of local and regional bus services run by national operators such as Stagecoach and Arriva, with most regional services stopping at major centres in the city, such as CMK (including Milton Keynes Central railway station), Bletchley, Wolverton and Magna Park.[212] The City Council also operates an on demand bus service known as "MK Connect", which serves the whole unitary authority area.[213]

Milton Keynes is served by (and, via its Redway network, provides part of) routes 6 and 51 on the National Cycle Network.[100][101]

The nearest international airport is London Luton and is easily reached by coach.[214] Cranfield Airport, an airfield, is 8 miles (13 km) away.[215]

Demographics

[edit]

At the 2011 census, the population of the Milton Keynes urban area, including the adjacent Newport Pagnell and Woburn Sands, was 229,941.[7] The population of the borough in total was 248,800,[216] compared with a population of around 53,000 for the same area in 1961.[217] In 2016, the Office for National Statistics estimated that the Borough population will reach 300,000 by 2025.[58] The 2021 census records the population of the Milton Keynes Built-up Area as 264,349,[218] and that of the Borough (now City) as 287,060.[219]

According to the 2011 census, the average age of the population is lower than is typical for the UK's 63 primary urban areas: 25.3% of the borough population were aged under 18 (5th place) and 13.4% were aged 65+ (57th out of 63).[220][7] The mean age is 35.7 and the median age is 35.[7] 18.5% of residents were born outside the UK (11th).[220] At the 2011 census, the ethnic profile was 78.9% white, 3.4% mixed, 9.7% Asian/Asian British, 7.3% Black/African/Caribbean/Black British, and 0.7% other.[7] The religious profile was that 62.0% of people were reported having a religion and 31.4% having none; the remainder declined to say: 52% are Christian, 5.1% Muslim, 3.0% Hindu; other religions each had less than 1% of the population.[7]

Economy, finances and business

[edit]

In 2014 and 2017, Milton Keynes ranked third in terms of contribution to the national economy, as measured by gross value added per worker, of the 63 largest conurbations in the UK.[221][222] In 2020, its ranking slipped to seventh.[220]

Major businesses

[edit]Milton Keynes has consistently benefited from above-average economic growth, ranked as one of the UK's top five cities.[223] In 2020 it was ranked sixth of 63 for business startups (per 10,000 people).[220]

Milton Keynes is home to several national and international companies, notably Domino's Pizza,[224] Marshall Amplification,[225] Mercedes-Benz,[226] Suzuki,[227] Volkswagen Group,[228] Red Bull Racing,[229] Network Rail,[230] and Yamaha Music Europe.[231]

Santander UK and the Open University are major employers locally.[232][233]

Small and medium enterprise

[edit]In 2013,[u] 99.4% of enterprises being SMEs, just 0.6% of businesses locally employ more than 250 people (but more than one third of employees),[235] whereas 81.5% employ fewer than 10 people.[235] The 'professional, scientific and technical sector' contributes the largest number of business units, 16.7%.[235] The retail sector is the largest contributor of employment.[235][7] Milton Keynes has one of the highest number of business start-ups in England, but also of failures.[220] Although education, health and public administration are important contributors to employment, the contribution is significantly less than the averages for England or the South East.[235]

Employment

[edit]Of the population, 75% is economically active, including 8.3% (of the population) who are self-employed;[7] 90% work in service industries of various sorts (of which wholesale and retail is the largest sector) and 9% in manufacturing.[7]

Social inequality

[edit]In 2015, the City of Milton Keynes had nine "lower super output areas"[v] that are in the 10% most deprived in England, but also had twelve 'lower super output areas' in the 10% least deprived in England.[237] This contrast between areas of affluence and areas of deprivation in spite of a thriving local economy, inspired local charity The Community Foundation (in its 2016 "Vital Signs" report) to describe the position as a "Tale of Two Cities".[238]

In 2018, the number of homeless young people sleeping rough in tents around CMK attracted national headlines as it became the apex of a national problem of poverty, inadequate mental health care and unaffordable housing.[239][240] On a visit to refurbishment and extension work on the YMCA building, Housing Minister Heather Wheeler declared that "Nobody in this day and age should be sleeping on the street".[241]

Notable people

[edit]Sports

[edit]- Charles Ademeno, former professional footballer[242]

- Dele Alli, professional footballer[243]

- Andrew Baggaley, English table tennis champion[244]

- Brothers George and Sam Baldock, professional footballers.[245][246][247]

- Ben Chilwell, professional footballer[248]

- Chris Clarke, English sprinter[249]

- Lee Hasdell, professional Mixed martial artist and Kickboxer[250]

- James Hildreth, professional cricketer[251]

- Liam Kelly, professional footballer[252]

- Kwame Nkrumah-Acheampong the only Ghanaian winter Olympian.[253]

- Craig Pickering, English sprinter[254]

- Ian Poulter, PGA & European Tour golf professional. Member of the 2010 and 2012 European Ryder Cup Teams[255]

- Mark Randall, professional footballer[256]

- Antonee Robinson, professional footballer[257]

- Greg Rutherford, long jump gold medallist for Team GB at the 2012 Olympic Games[258]

- Ed Slater, professional rugby union player[259]

- Fallon Sherrock, professional darts player.[260]

- Sam Tomkins, professional rugby league player[261]

- Dan Wheldon (1978–2011), Indy car driver[262]

- Leah Williamson, professional footballer[263]

Business

[edit]- Jim Marshall (1923–2012), founder and CEO of Marshall Amplification was living in and ran his business from Milton Keynes when he died[264]

- Pete Winkelman, Chairman of Milton Keynes Dons Football Club, owner of Linford Manor recording studios, long-term resident[265]

Academic

[edit]- Christopher B-Lynch, (visiting) Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Cranfield University, responsible for inventing the eponymously named B-Lynch suture[266][267]

- Alan P. F. Sell (1935–2016), academic and theologian lived in Milton Keynes in his later years and died there[268][269]

- Alan Turing (1912–1954), played a significant role in the creation of the modern computer. He lodged at the Crown Inn, Shenley Brook End, while working at Bletchley Park[270]

Stage, screen and media

[edit]- Errol Barnett, an anchor and correspondent for CNN[271]

- Emily Bergl, an actress known for her roles in Desperate Housewives and Shameless[272]

- Emika, born Ema Jolly, a musical artist[273]

- Richard Macer, documentary maker[274]

- Clare Nasir, the meteorologist, TV and radio personality, was born in Milton Keynes in 1970[275]

- Kevin Whately, professional actor[276]

Literature

[edit]- Sarah Pinborough, English horror writer[277]

- Jack Trevor Story, novelist, was a long-term resident of Milton Keynes[278]

Politics

[edit]- Frank Markham (Sir Sydney Frank Markham, MP) (1897–1975), born in Stony Stratford and was local MP (1951–1964).[279]

- Nat Wei, Baron Wei, member of the House of Lords (born in Watford, grew up in Milton Keynes)[280]

Music

[edit]Individual

[edit]- Bob Leith, drummer for the Kingston upon Thames band Cardiacs and others went to school in Milton Keynes and formed his first bands there including Part 1[281]

- Adam Ficek, drummer of London band Babyshambles[282]

- Gordon Moakes, the bassist for the London-based rock band Bloc Party[283]

Bands

[edit]- Capdown, a ska punk band, came from and formed in Milton Keynes in 1997[284]

- Fellsilent, a metal band, come from and formed in Milton Keynes in 2003[285][286]

- Tesseract, a djent band, formed as a full live act in Milton Keynes in 2007.[287] Tesseract's guitarist, songwriter and producer Acle Kahney is also a former member of Fellsilent.[286]

- Hacktivist, a Grime and djent band[288]

- RavenEye, the rock band, formed in Milton Keynes in 2014[289]

Freedom of the City

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Date of the "new town designation order"

- ^ a b From Milton Keynes Bowl to Marble Arch via Watling Street is 46 miles (74 km).[2] By rail from Milton Keynes Central to Euston is 49 miles 65 chains (49.81 mi; 80.17 km).[3] From Central Milton Keynes to Charing Cross via the M1 motorway is 55 miles (89 km).[4]

- ^ The area that is the subject of this article, the contiguous urban segment of the City of Milton Keynes local authority area, does not have legal city status itself although it is usually known as "the city". The Letters Patent were awarded to the responsible local authority rather than to the settlement itself. See section § Formal award of city status below for more details.

- ^ The adjacent towns of Newport Pagnell and Woburn Sands were not included in the original 1967 designated area of the new town but have become part of the Milton Keynes urban area since then.[7]

- ^ The Plan for Milton Keynes begins (in the Foreword by Lord ("Jock") Campbell of Eskan): "This plan for building the new city of Milton Keynes ... "

- ^ population over 50,000.

- ^ population over 100,000. St Albans, a cathedral city of 57,000, is closer.

- ^ The Woburn weather station is located 7.0 miles (11.3 km) from the Milton Keynes city centre. There is another station at Stowe, just outside Buckingham about 12 miles (19 km) distant. On 19 July 2022, the temperature here reached 38.7 °C (101.7 °F).[72]

- ^ Weather station is located 7.0 miles (11.3 km) from the city centre.

- ^ and erstwhile lecturer in urban planning at University College London

- ^ In reality, the bus operators have specified many bus routes that go through, rather than between, neighbourhoods.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt report the Corporation as concerned at this outcome, which was an unanticipated emergent behaviour. In later developments, it aimed for increased permeability through the grid.[93]

- ^ An additional ten-metre wide strip was originally specified to satisfy Buckinghamshire County Council's belief in a future fixed-track public transport system. In 1977 MKDC decided to cease to specify it.[96]

- ^ The 'western expansion area' is what became Fairfields and Whitehouse. The 'eastern expansion area' is Broughton including Brooklands. 'The Hub' is a development of residential tower, hotels and restaurants in CMK.

- ^ Large-scale buildings include Jurys Inn (10 storeys)[104] The Pinnacle:MK on Midsummer Boulevard (9 storeys)[105] and the Vizion development on Avebury Boulevard (12 storeys),[106]

- ^ The Network Rail National Centre is at the western limit of Silbury Boulevard near the Central station; this building complex occupies a large land area but only rises to the equivalent of six storeys;[108] The Hotel la Tour (Marlborough Gate and Midsummer Bvd) opens April 2022 and is 50 metres tall.[109]

- ^ a b Not in original designated area but subsequent expansion has grown to include it.[7]

- ^ /ˈbrɔːtən/, as in brought; /ˈlaʊtən/, as in bough; and /ˈwʊftən/, as in enough, respectively

- ^ some areas may receive BBC South and ITV Meridian, but it is outside their allocated area.[180]

- ^ A competing paper, MK News, closed in October 2016.[184]

- ^ An updated report for 2016 is available but does not give this data.[234]

- ^ A "lower super output area" is a small geographic area defined by the Office of National Statistics to contain 1,000 to 1,500 residents and thus to permit consistent national comparisons.[236]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d "North Buckinghamshire (Milton Keynes) New Town (Designation) Order". The London Gazette (44233): 827. 24 January 1967. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2014.)

- ^ a b According to a nearby historic milestone (see Ordnance Survey (1885). "Buckinghamshire Sheet XV" (Map). OS Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952. 1:10,560. Ordnance Survey – via National Library of Scotland.

- ^ a b "Engineer's Line References". RailwayCodes.org. 28 July 2018. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Central Milton Keynes to Charing Cross". Google Maps. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "UNITED KINGDOM: Countries and Major Urban Areas". Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ "Figure 1: Explore population characteristics of individual BUAs". Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Milton Keynes built-up area (E34005056)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 August 2020. (2011 census)

- ^ Maslen, T. J. (1843). Suggestions for the improvement of Our Towns and Houses. London: Smith, Elder. (Quoted in Walter L Crease, The search for Environment, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1966, p319).

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 265.

- ^ a b c South East Study 1961–1981 (Report). London: HMSO. 1964.

A big change in the economic balance within the south east is needed to modify the dominance of London and to get a more even distribution of growth

cited in The Plan for Milton Keynes (Llewellyn-Davies et al (1970), page 3 - ^ "Bletchley Pioneers, Planning, & Progress". Clutch.open.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Early days of overspill". Clutch.open.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Need for more planned towns in the South-East". The Times. 2 December 1964.

- ^ "Urgent action to meet London housing needs". The Times. 4 February 1965.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. xi.

- ^ a b c Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 8.

- ^ "Area of New Town Increased by 6000 acres". The Times. 14 January 1966.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 4.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 3.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies; Forestier-Walker; Bor (December 1968). Milton Keynes: Interim Report to Milton Keynes Development Corporation. Milton Keynes Development Corporation.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. xii.

- ^ Croft, R. A.; Mynard, Dennis C.; Gelling, Margaret (1993). The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes. Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society Monograph Series. Aylesbury: Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society. ISBN 9780949003126. OCLC 29216206.

The creation of Milton Keynes provided an opportunity to study an extensive rural landscape before it was changed irreversibly. This book brings together the results of 20 years of excavation, fieldwork and documentary studies carried out by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation.

- ^ a b Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 107.

- ^ "Architectural Design 6, 1973. Special issue: Milton Keynes". Architectural Design. 1973. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019. Staff of MKDC on the cover of Architectural Design

- ^ "AJ archive: Milton Keynes planning study (1969)". The Architects' Journal. 1969. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019. reprint 23 January 2017

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), pp. 1, 47.

- ^ a b c Barkham, Patrick (3 May 2016). "The struggle for the soul of Milton Keynes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Clapson (2014), p. 3.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. xii.

- ^ Milton Keynes: A Living Landscape, Fred Roche Foundation, 2018

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 33.

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 14.

- ^ a b Bishop, Jeffrey (1981). Milton Keynes – the Best of Both Worlds? Public and professional views of a new city. University of Bristol School for Advanced Urban Studies. ISBN 9780862922245. OCLC 756979521.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 46.

- ^ a b Walker The Architecture and Planning of Milton Keynes, Architectural Press, London 1981. Retrieved 13 February 2007

- ^ Webber, M (1963). "Order in Diversity: Community Without Propinquity". In Wingo, Lowdon (ed.). Cities and space : the future use of urban land ; essays from the fourth RFF forum. Baltimore: Hopkins. OCLC 710950. ISBN 9780801806773

- ^ "MILTON KEYNES PARTNERSHIP COMMITTEE ROLE AND REMIT". Milton Keynes Council. 7 September 2005. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "This is not a city: Milton Keynes". The Open University. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Milton Keynes city status application" (PDF). Milton Keynes City Council. December 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ "Crown Office". The London Gazette (63791). TSO. 18 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Richings, James (16 March 2024). "Milton Keynes named one of the best places to live in the UK". Bucks Free Press.

Forget the 1970s image of concrete cows, endless roundabouts and ugly architecture, the new town turned city deserves its place on the Sunday Times list.

- ^ Davis, Matthew (15 March 2024). "Why Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, is one of the best places to live 2024". Sunday Times.

- ^ a b Dave Persaud. "Father of the New City". Milton Keynes: Living Archive.

- ^ a b "Parishes : Milton Keynes". A History of the County of Buckingham. Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. 4. Constable & Co. Ltd. 1927. pp. 401–405. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Archaeology in the Milton Keynes District: Stone Age". Milton Keynes Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Archaeology in the Milton Keynes District: Bronze Age". Milton Keynes Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Object 2234: "Gold stater ('Gallo-Belgic A' type) Roman, mid-2nd century BC Probably made in northern France or Belgium; found at Fenny Stratford near Milton Keynes, England"". British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ "Archaeology in the Milton Keynes District: archaeological sites and artefacts found at Bancroft and Blue Bridge, part of the old farmland of Stacey Hill Farm, now Milton Keynes Museum". Milton Keynes Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ a b Mynard, Dennis; Hunt, Julian (1994). Milton Keynes, a pictorial history. Chichester, West Sussex: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-940-6.

- ^ Domesday Book, Buckinghamshire

- ^ Page (1927), p. 268–269, Newport Hundred: Introduction.

- ^ a b Page (1927), pp. 274–283, Parishes: Bletchley with Fenny Stratford and Water Eaton.

- ^ a b Page (1927), p. 505–509, Parishes: Wolverton.

- ^ "The Milton Keynes hoard". British Museum/Google Cultural Institute. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Copeland (2006), Introduction p. 2.

- ^ "Bletchley Park welcomes 2015's 200,000th visitor". Bletchley Park. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 273.

- ^ a b "Milton Keynes at 50: Success town has 'nothing to be ashamed of'". BBC. 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ "Labour Market Profile – South East". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Regional scale map of region". OpenStreetMap. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "National scale map of region". OpenStreetMap. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Horton, A.; Coleman, B. E.; Cox, B. M.; Shephard-Thorn, E. R.; Morter, A. A.; Penn, I. E.; Thurrell, R. G.; Ivimey-Cook, H. C. (1974), The geology of the new town of Milton Keynes, Natural Environment Research Council Institute of Geological Sciences, archived from the original on 6 March 2019, retrieved 3 March 2019

- ^ "Central Milton Keynes 1:25000 (Ordnance Survey mapping)". Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Woodlhill 1:25000 (Ordnance Survey mapping)". Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Newport Pagnell 1:25000 (Ordnance Survey mapping)". Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "City has been built to avoid worst flooding". Milton Keynes Citizen. 13 February 2014. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Activities". Milton Keynes Parks Trust. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ a b "WakeMK relaunches with new management". Destination MK. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Wildlife Sites". Milton Keynes Natural History Society. 6 September 2015. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Little Linford Wood". Berks, Bucks and Oxon Wildlife Trust. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Synoptic and climate stations (map)". Met Office. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Unprecedented extreme heatwave, July 2022" (PDF). Metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Booth, George (2007). "1947 minimum". Weather. 62 (3): 61–68. doi:10.1002/wea.66. S2CID 123612433.

- ^ Rogers, Simon (21 December 2010). "2010 minimum". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Woburn Climate Station, Climate period:1991–2020". Met Office. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature, Monthly Extreme Minimum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Melvin, Jeremy (12 August 2014). "Richard MacCormac (1938–2014)". Architectural Review. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ Hatherley, Owen (2010). A guide to the new ruins of Great Britain (PDF). New York: Verso. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84467-700-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Building of the month: Heelands Housing, Milton Keynes". Twentieth Century Society. January 2008. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Pitcher, Greg (12 March 2018). "A Milton Keynes housing estate designed by Ralph Erskine in the 1970s should be designated a conservation area, a heritage body has urged". The Architects' Journal. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Billings, Henrietta (February 2013). "Obituary: John Winter". Twentieth Century Society. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 95.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 104.

- ^ "1979: Milton Keynes shopping building". The Twentieth Century Society. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Shopping building, Milton Keynes: Grade II listed". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Public Art in MK". Milton Keynes Council. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Milton Keynes: Who forgot the urban design" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b Edwards, Michael (2001). "City Design: What Went Wrong at Milton Keynes?" (PDF). Journal of Urban Design. 6, 2001 (1): 87–96. doi:10.1080/13574800120032905. S2CID 108812232. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Kitchen, Roger; Hill, Marion (2007). 'The story of the original CMK' ... told by the people who shaped the original Central Milton Keynes (interviews). Milton Keynes: Living Archive. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-904847-34-5. OCLC 244982027. Retrieved 26 January 2009. (Lock is visiting professor of town planning at Reading University. He was the chief town planner for CMK.) (Ten miles is about 16 kilometres and 18,000 acres is about 7,300 hectares),

- ^ Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 16.

- ^ Walker, Derek (1982). The Architecture and Planning of Milton Keynes. London: Architectural Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85139-735-1. OCLC 8685851. cited in Clapson, Mark (2004). A Social History of Milton Keynes: Middle England/Edge City. London: Frank Cass. pp. 40. ISBN 978-0-7146-8417-8. OCLC 1126356133.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), pp. 175–178.

- ^ a b Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 175.

- ^ a b c Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 36.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 177.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), pp. 170, 171.

- ^ Chalmers, Theo (19 September 2012). "The curse of the living planners" (PDF). Milton Keynes Business Week. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Redways". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 178.

- ^ a b "National cycle route 6". Sustrans. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ a b "National cycle route 51". Sustrans. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Murrer, Sally (13 May 2021). "Tallest and shiniest building in Milton Keynes is topped out at 50 metres this week". Milton Keynes Citizen. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Milton Keynes high-rise plan revealed". BBC News. 5 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Jurys Inn, Milton Keynes (McAleer & Rushe, Design and build)". www.mcaleer-rushe.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "The Pinnacle, Milton Keynes – Building #6483". www.skyscrapernews.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Vizion, Milton Keynes – Building #5201". www.skyscrapernews.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "The CMK Business Neighbourhood Plan". Central Milton Keynes town council. October 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Network Rail opens The Quadrant:MK". Railway Gazette International. 11 June 2012. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Murrer, Sally (13 May 2021). "Tallest and shiniest building in Milton Keynes is topped out at 50 metres this week". Milton Keynes Citizen. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Davies et al. (1970), p. 27.

- ^ a b c Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 174.

- ^ "Peter Youngman, Architect of the modern British landscape". The Guardian. 17 June 2005. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), pp. 171–174.

- ^ a b Pevsner, Williamson & Brandwood (2000), p. 487.

- ^ Clare Turner (27 April 2020). "Milton Keynes ranks top for green space". Milton Keynes Citizen. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Research by the think tank [the] Centre for Cities shows the varying amounts of space – inside and out – available to residents in 62 urban areas across Britain.

- ^ "About the Parks Trust". The Parks Trust.

- ^ a b c "The Parks Trust model". The Milton Keynes Parks Trust. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Parks & Lakes". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Browne, Paige (23 December 2018). "Millions of trees in Milton Keynes to be spruced up in 2019". Milton Keynes Citizen. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 259.

- ^ "Facts and Figures". Milton Keynes Parks Trust. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019. "The Parks Trust looks after over 6,000 acres of parkland and green space". The urban area measures approximately 30,000 acres (12,000 ha).

- ^ a b Bendixson & Platt (1992), pp. 129–154.

- ^ "Shopping". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Milton Keynes Theatre & Art Gallery Complex". Architects' Journal Building Library. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019. Includes photographs, drawings and working details.

- ^ a b "Culture". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Entertainment". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Where to stay". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "The Church of Christ the Cornerstone". Baptist Union / Church of England / Methodist Church / Roman Catholic Church / United Reformed Church. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Civic Offices". Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Central opened". Railway Magazine. Vol. 128, no. 974. June 1982. p. 258. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ^ Historic England. "Campbell Park, Milton Keynes (1467405)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Milton Keynes Heritage (map) – English Partnerships, 2004.

- ^ a b Page (1927), p. 283–288, Parishes: Bradwell.

- ^ Historic England. "Bradwell Abbey: a Benedictine priory, chapel and fishpond (1009540)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Houses of Benedictine monks: The priory of Bradwell". A History of the County of Buckingham. Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. 1. Constable & Co. Ltd. 1905. p. 350–352. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Chapel to North of Bradwell Abbey House (1125271)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Woodfield (1986), p. 19–24.

- ^ "From Railway line to Railway Walk". New Bradwell Heritage. Milton Keynes Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Bradwell Windmill". Milton Keynes Museum. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Page (1927), p. 387–392, Parishes: Great Linford.

- ^ a b "Milton Keynes Arts Centre". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Page (1927), p. 401–405, Parishes: Milton Keynes.

- ^ Woodfield (1986), p. 84.

- ^ R. H. Britnell, 'The Origins of Stony Stratford', Records of Buckinghamshire, XX (1977), pp. 451–3

- ^ Page (1927), p. 476–482, Parishes: Stony Stratford.

- ^ Bendixson & Platt (1992), p. 74.

- ^ "Willen Church". Westminster School. 2007. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Woodfield (1986), p. 165.

- ^ "Peace Pagoda". Milton Keynes Parks Trust. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Buckinghamshire Historical Service plaque on site

- ^ Morice, Dave (2005). "Kickshaws". Butler University. p. 228. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Murrer, Sally (13 June 2022). "The 6 most mispronounced Milton Keynes place names people are always getting wrong". Milton Keynes Citizen. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Cooksey, G. W. (6 March 1976). Kelly, A. V. (ed.). The Scope Of Education And Its Opportunities For The 80s. Goldsmiths College March Education Conference. Goldsmiths College, University of London. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "An extremely select spot". The Independent. 27 June 1996. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Explainer: The history of grammar schools". ITV News. 15 October 2015. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Independent schools in Milton Keynes – ISC". www.isc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "Project Two: MK:U A new University for Milton Keynes". MK2050 Futures Commission. October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Fulcher, Merlin (31 January 2019). "Competition: MK:U, Milton Keynes". The Architects' Journal. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Murrer, Sally (19 January 2023). "Milton Keynes' plan to create world-class university in tatters after government refuses multi million pound funding". Milton Keynes Citizen. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Murrer, Sally (26 June 2023). "World famous Open University could move lock stock and barrel to new site in Central Milton Keynes". Milton Keynes Citizen.

- ^ a b "MK City Discovery Centre". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "National Bowl at Milton Keynes, UK – seeking expressions of interest from developers and partners". www.psam.uk.com. PanStadia & Arena Management. 6 August 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "World Class Music and Entertainment". The Stables. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "National Youth Music Camps". The Stables. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Milton Keynes International Festival 2018". Heart FM. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "MK City Orchestra". Milton Keynes Council. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Gallery". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Cinema in Milton Keynes". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Williams, Fran (11 March 2019). "MK Gallery by 6a architects to open doors this weekend". The Architects' Journal. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Brown, Paige (1 March 2019). "New cinema set to open in Milton Keynes this month". Milton Keynes Citizen. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Milton Keynes Theatre & Art Gallery Complex". Architects' Journal Building Library. 1999. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019. Includes photographs, drawings and working details.

- ^ Barron, Michael (28 September 2009). Auditorium Acoustics and Architectural Design. Spon Press. ISBN 9780419245100. OCLC 466909636.

- ^ "Stantonbury Theatre". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Bletchley Park". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "National Museum of Computing". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "MK Museum". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Trails, Guides, Walks & Maps: Arts & Cultural Venues Map". Milton Keynes Council. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Westbury Arts Centre". Destination MK. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "ANGLIA". ITV media. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Meridian". ITV media. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Ofcom awards four new community radio licences". OFCOM. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Radio for Milton Keynes". CRMK. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Citizen". Audit Bureau of Circulation. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Trinity Mirror closes newspapers in Milton Keynes, Luton and Northampton as Local World purge continues". Press Gazette. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Sports and activities". Destination Milton Keynes. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Badminton England". Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Best practice don't repel the borders". Local Government Chronicle. 19 April 2006. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Willen Lake North". The Parks Trust. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Robot company Starship Technologies start Milton Keynes deliveries". BBC News. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2023.