Miracles of Jesus

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The miracles of Jesus are the many miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian texts, with the majority of these miracles being faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.[1][2]

In the Gospel of John, Jesus is said to have performed seven miraculous signs that characterize his ministry, from changing water into wine at the start of his ministry to raising Lazarus from the dead at the end.[3]

For many Christians and Muslims, the miracles are believed to be actual historical events.[4][5][6] Others, including many liberal Christians, consider these stories to be figurative.[a]

Since the Age of Enlightenment, many scholars have taken a highly skeptical approach to claims about miracles.[7] There is less agreement on the interpretation of miracles than in former times, though there is a scholarly consensus that the Historical Jesus was viewed as a miracle-worker during his lifetime.[8] Non-religious historians commonly avoid commenting on the veracity of miracles as the sources are limited and considered problematic.[9] Some scholars rule out miracles altogether while others defend the possibility, either with reservations or more strongly[8] (in the latter case commonly reflecting religious views).[9]

Types and motives

[edit]In most cases, Christian authors associate each miracle with specific teachings that reflect the message of Jesus.[10]

In The Miracles of Jesus, H. Van der Loos describes two main categories of miracles attributed to Jesus: those that affected people (such as Jesus healing the blind man of Bethsaida), or "healings", and those that "controlled nature" (such as Jesus walking on water). The three types of healings are cures, in which an ailment is miraculously remedied, exorcisms, in which demons are cast out of victims, and the resurrection of the dead. Karl Barth said that, among these miracles, the Transfiguration of Jesus is unique in that the miracle happens to Jesus himself.[11]

According to Craig Blomberg, one characteristic shared among all miracles of Jesus in the Gospel accounts is that he delivered benefits freely and never requested or accepted any form of payment for his healing miracles, unlike some high priests of his time who charged those who were healed.[12] In Matthew 10:8 he advised his disciples to heal the sick without payment and stated, "Freely ye received, freely give."[12]

It is not always clear when two reported miracles refer to the same event. For example, in the healing the centurion's servant, the Gospels of Matthew[13] and Luke[14] narrate how Jesus healed the servant of a centurion in Capernaum at a distance. The Gospel of John[15] has a similar but slightly different account at Capernaum and states that it was the son of a royal official who was cured at a distance.

Healing those who were ill and infirm

[edit]The largest group of miracles mentioned in the Gospels involves healing people who are ill, infirm or disabled. The Gospels give varying amounts of detail for each episode: sometimes Jesus cures simply by saying a few words; at other times, he employs material such as spit and mud. Luke 4:40 glosses over many healings at one time: "all those who ... were sick ... were brought to Him, and He laid His hands on every one of them and healed them."[16]

Blind people

[edit]The canonical Gospels contain a number of stories about Jesus healing blind people. The earliest is a story of the healing of a blind man in Bethsaida in the Gospel of Mark.[17]

Mark's gospel gives an account of Jesus healing a blind man named Bartimaeus as Jesus is leaving Jericho.[18] The Gospel of Matthew[19] has a simpler account loosely based on this, with two unnamed blind men instead of one (this "doubling" is a characteristic of Matthew's treatment of Mark's text) and a slightly different version of the story, taking place in Galilee, earlier in the narrative.[20] The Gospel of Luke tells the same story of Jesus healing an unnamed blind man but moves the event in the narrative to when Jesus approaches Jericho.[21][22]

The Gospel of John describes an episode in which Jesus heals a man blind from birth, placed during the Festival of Tabernacles, about six months before his crucifixion. Jesus mixes spittle with dirt to make a mud mixture, which he then places on the man's eyes. He instructs the man to wash his eyes in the Pool of Siloam. When the man does this, he is able to see. When asked by his disciples whether the cause of the blindness was the man's sins or his parents' sins, Jesus states that it was due to neither.[23]

Lepers

[edit]A story in which Jesus cures a leper appears in Mark 1:40–45, Matthew 8:1–4 and Luke 5:12–16. Having cured the man, Jesus instructs him to offer the requisite ritual sacrifices as prescribed by the Deuteronomic Code and Priestly Code and to not tell anyone who had healed him. But the man disobeyed, increasing Jesus's fame, and thereafter Jesus withdrew to deserted places but was followed there.

In an episode in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 17:11–19), while on his way to Jerusalem, Jesus sends ten lepers who sought his assistance to the priests, and they were healed as they go, but the only one who comes back to thank Jesus is a Samaritan.

Paralytics

[edit]Healing the paralytic at Capernaum appears in Matthew 9:1–8, Mark 2:1–12 and Luke 5:17–26. The Synoptics state that a paralytic was brought to Jesus on a mat; Jesus told him to "get up and walk", and the man did so. Jesus also told the man that his sins were forgiven, which irritated the Pharisees. Jesus is described as responding to the anger by asking whether it is easier to say that someone's sins are forgiven, or to tell the man to "get up and walk". Mark and Luke state that Jesus was in a house at the time, and that the man had to be lowered through the roof by his friends due to the crowds blocking the door.

A similar cure is described in the Gospel of John as the healing the paralytic at Bethesda[24] and occurs at the Pool of Bethesda. In this cure Jesus also tells the man to take his mat and walk.[25]

Women

[edit]The curing of a bleeding woman appears in Mark 5:21–43, Matthew 9:18–26 and Luke 8:40–56, along with the miracle of the daughter of Jairus.[26] The Gospels state that while heading to Jairus's house, Jesus was approached by a woman who had been bleeding for twelve years and that she touched Jesus's cloak (fringes of his garment) and was instantly healed. Jesus turned about and, when the woman came forward, said, "Daughter, your faith has healed you; go in peace".

The Synoptics[27] describe Jesus as healing the mother-in-law of Simon Peter when he visited Simon's house in Capernaum, around the time of Jesus recruiting Simon as an Apostle (Mark records the event occurring just after the calling of Simon, while Luke records it just before). The Synoptics imply that this led other people to seek out Jesus.

Jesus healing an infirm woman appears in Luke 13:10–17. While teaching in a synagogue on the Sabbath, Jesus cured a woman who had been crippled by a spirit for eighteen years and could not stand straight at all.

Other healings

[edit]The healing of a man with dropsy is described in Luke 14:1–6. In this miracle, Jesus cured a man with dropsy at the house of a prominent Pharisee on the Sabbath. Jesus justified the cure by asking, "If one of you has a child or an ox that falls into a well on the Sabbath day, will you not immediately pull it out?"

In the healing of the man with a withered hand,[28] the Synoptics state that Jesus entered a synagogue on Sabbath and found a man with a withered hand, whom Jesus healed, having first challenged the people present to decide what was lawful for Sabbath—to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill. The Gospel of Mark adds that this angered the Pharisees so much that they started to contemplate killing Jesus.

The miraculous healing the deaf mute of Decapolis only appears in the Gospel of Mark.[29] Mark states that Jesus went to the Decapolis, met a man there who was deaf and mute, and cured him. Specifically, Jesus first touched the man's ears, then touched his tongue after spitting, and then said, "Ephphatha!", an Aramaic word meaning "be opened".

The miraculous healing of a centurion's servant is reported in Matthew 8:5–13 and Luke 7:1–10. These two Gospels narrate how Jesus healed the servant of a centurion in Capernaum. John 4:46–54 has a similar account at Capernaum but states that it was the son of a royal official who was healed. In both cases the healing took place at a distance.

Jesus healing in the land of Gennesaret appears in Matthew 14:34–36 and Mark 6:53–56. As Jesus passes through Gennesaret all those who touch his cloak are healed.

Matthew 9:35–36 also reports that after the miracle of Jesus exorcising a mute, Jesus went through all the towns and villages, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom and healing every disease and sickness.

The healing of Malchus was Christ's final miracle before his resurrection. Simon Peter had cut off the ear of the High Priest's servant, Malchus, during the scene in the Garden of Gethsemane. Jesus restored the ear by touching it with his hand.

Exorcisms

[edit]According to the three Synoptic Gospels, Jesus performed many exorcisms of demons. These incidents are not mentioned in the Gospel of John and appear to have been excluded due to theological considerations.[30]

The seven major exorcism accounts in the Synoptic Gospels which have details, and imply specific teachings, are as follows:

- Exorcism at the Synagogue in Capernaum—Jesus exorcises an evil spirit who cries out, "What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!"[31]

- Exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac or Miracle of the (Gadarene) Swine—Jesus exorcises a possessed man (changed in the Gospel of Matthew to two men). When Jesus asks the demon's name (finding the name of the possessing demon was an important traditional tool of exorcists),[32] he is given the reply Legion, "for we are many". When the demons ask to be expelled into a nearby group of pigs rather than be sent out of the area, Jesus obliges, but the pigs then run into the lake and drown.[33]

- Exorcism of the Syrophoenician woman's daughter (Matthew 15:21–28 and Mark 7:24–30)—A Gentile woman asks Jesus to heal her daughter, but Jesus refuses, saying that he has been sent only to "the lost sheep of the house of Israel". The woman persists, saying that "dogs eat of the crumbs which fall from their masters' table". In response Jesus relents and informs her that her daughter has been healed.[34]

- Exorcising the blind and mute man (Matthew 12:22–32, Mark 3:20–30, and Luke 11:14–23)—Jesus heals a possessed man who is blind and mute. People are astonished and ask, "Could this be the Son of David?"

- Exorcising a boy possessed by a demon (Matthew 17:14–21, Mark 9:14–29, and Luke 9:37–49)—A boy possessed by a demon is brought forward to Jesus. The boy is said to have foamed at the mouth, gnashed his teeth, become rigid, and involuntarily fallen into both water and fire. Jesus's followers could not expel the demon, and Jesus condemns the people as unbelieving, but when the father of the boy questions if Jesus could heal the boy, he replies "everything is possible for those that believe". The father then says that he believes and the child is healed.[35]

- Jesus exorcising at sunset (Matthew 8:16–17, Mark 1:32–34, and Luke 4:40–41)—This miracle appears in the Synoptic Gospels just after Jesus heals Simon Peter's mother-in-law. In this miracle, Jesus heals people and casts out demons.

- Jesus exorcising a mute (Matthew 9:32–34)—This miracle immediately follows the account of Jesus healing two blind men. A man who is possessed and can not talk is brought to Jesus, who casts out the demon. The man is then able to speak.

There are also brief mentions of other exorcisms, such as the following:

- Jesus casts seven devils out of Mary Magdalene. (Mark 16:9, Luke 8:2)

- Jesus continues to cast out devils even though Herod Antipas wants to kill him. (Luke 13:31–32)

Resurrection of the dead

[edit]All four canonical gospels describe the resurrection of Jesus; three of them also relate a separate occasion on which Jesus calls a dead person back to life:

- Daughter of Jairus.[36][37][38] Jairus, a major patron of a synagogue, asks Jesus to heal his daughter, but while Jesus is on the way, Jairus is told his daughter has died. Jesus tells him she was only sleeping and wakes her with the words Talitha kum!

- The Young Man from Nain.[39] A young man, the son of a widow, is brought out for burial in Nain. Jesus sees her, and his pity causes him to tell her not to cry. Jesus approaches the coffin and tells the man inside to get up, and he does so.

- The Raising of Lazarus.[40] A close friend of Jesus who had been dead for four days is brought back to life when Jesus commands him to get up.

Harmony with nature

[edit]The Gospels include eight pre-resurrection accounts concerning Jesus's power over nature:

- Turning water into wine at a wedding, when the host runs out of wine, the host's servants fill vessels with water at Jesus's command, then a sample is drawn out and taken to the master of the banquet who pronounces the content of the vessels as the best wine of the banquet.

- The miraculous catch of fish takes place early in Jesus's ministry and results in Saint Peter, Saint Andrew, James, son of Zebedee, and John the Apostle joining Jesus as his apostles.[41]

- Walking on water – Jesus walks on water.

- Calming the storm – during a storm, the disciples woke Jesus, and he rebuked the storm causing it to become calm. Jesus then rebukes the disciples for lack of faith.

- Finding a coin in the fish's mouth is reported in Matthew 17:24–27.[42]

- Cursing the fig tree – Jesus cursed a fig tree, and it withered.

Post-resurrection miracles attributed to Jesus are also recorded in the Gospels:

- A miracle similar to the miraculous catch of fish, also called the catch of 153 fish to distinguish it from the account in Luke, is reported in the Gospel of John but takes place after the Resurrection of Jesus.

List of miracles found outside the New Testament

[edit]The Book of Mormon

[edit]The Book of Mormon, one of the religious texts of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,[43] records multiple miracles performed by Jesus. Sometime shortly after his Ascension, the Book of Mormon records that Jesus miraculously descends from heaven and greets a large group of people who immediately bow down to him. Jesus offers this invitation: "Arise and come forth unto me, that ye may thrust your hands into my side, and also that ye may feel the prints of the nails in my hands and in my feet, that ye may know that I am the God of Israel, and the God of the whole earth, and have been slain for the sins of the world" 3 Nephi 11:8–17.

In addition to descending from heaven, other miracles of Jesus found in the Book of Mormon include the following:

- Healing the "lame, or blind, or halt, or maimed, or leprous, or that are withered, or that are deaf, or that are afflicted in any manner" 3 Nephi 17:7–10.

- Providing bread and wine as emblems of his sacrifice and death to the multitude when neither had been brought 3 Nephi 20:3–7.

- Changing the nature of three of his called twelve disciples in the Book of Mormon so that they could live until his Second Coming and the other nine that they would live until the age of 72 and be taken "up to his kingdom" 3 Nephi 28:1–23.

Infancy Gospels

[edit]Accounts of Jesus performing miracles are also found outside the New Testament. Later, 2nd century texts, called Infancy Gospels, narrate Jesus performing miracles during his childhood.

| Miracle | Sources |

| Rich young man raised from the dead- parallels the Lazarus story of John 11 | Secret Gospel of Mark 1 |

| Water controlled and purified | Infancy Thomas 2.2 |

| Made birds of clay and brought them to life | Infancy Thomas 2.3 |

| Resurrected dead playmate Zeno | Infancy Thomas 9 |

| Healed a woodcutter's foot | Infancy Thomas 10 |

| Held water in his cloak | Infancy Thomas 11 |

| Harvested 100 bushels of wheat from a single seed | Infancy Thomas 12 |

| Stretched a board that was short for carpentry | Infancy Thomas 13 |

| Resurrected a teacher he earlier struck down | Infancy Thomas 14–15 |

| Resurrected a dead child | Infancy Thomas 17 |

| Resurrected a dead man | Infancy Thomas 18 |

| Healed James' viper bite | Infancy Thomas 19 |

| Miraculous Virgin Birth verified by midwife | Infancy James 19–20 |

Miracles performed by Jesus are mentioned in two sections of the Quran (suras 3:49 and 5:110) in broad strokes with little detail or comment.[44]

Setting and interpretations

[edit]Cultural background

[edit]Miracles were widely believed in around the time of Jesus. Gods and demigods such as Heracles (better known by his Roman name, Hercules), Asclepius (a Greek physician who became a god) and Isis of Egypt all were thought to have healed the sick and overcome death (i.e., to have raised people from the dead).[45] Some thought that mortal men, if sufficiently famous and virtuous, could do likewise; there were myths about philosophers like Pythagoras and Empedocles calming storms at sea, chasing away pestilences, and being greeted as gods,[45] and similarly some Jews believed that Elisha the Prophet had cured lepers and restored the dead.[45] The achievements of the 1st century Apollonius of Tyana, though occurring after Jesus's life, were used by a 3rd-century opponent of the Christians to argue that Christ was neither original nor divine (Eusebius of Caesaria argued against the charge).[46]

The first Gospels were written against this background of Hellenistic and Jewish belief in miracles and other wondrous acts as signs—the term is explicitly used in the Gospel of John to describe Jesus's miracles—seen to be validating the credentials of divine wise men.[47]

Traditional Christian interpretation

[edit]Many Christians believe Jesus's miracles were historical events and that his miraculous works were an important part of his life, attesting to his divinity and the Hypostatic union, i.e., the dual natures of Jesus as God and Man.[48] They see Jesus's experiences of hunger, weariness, and death as evidences of his humanity, and miracles as evidences of his divinity.[49][50][51]

Christian authors also view the miracles of Jesus not merely as acts of power and omnipotence, but as works of love and mercy, performed not with a view to awe by omnipotence, but to show compassion for sinful and suffering humanity.[48][52] And each miracle involves specific teachings.[53]

Since according to the Gospel of John,[54] it was impossible to narrate all of the miracles performed by Jesus, the Catholic Encyclopedia states that the miracles presented in the Gospels were selected for a twofold reason: first for the manifestation of God's glory, and then for their evidential value. Jesus referred to his "works" as evidences of his mission and his divinity, and in John 5:36 he declared that his miracles have greater evidential value than the testimony of John the Baptist.[48] John 10:37–38 quotes Jesus as follows:[55]

Do not believe me unless I do what my Father does. But if I do it, even though you do not believe me, believe the miracles, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father.

In Christian teachings, the miracles were as much a vehicle for Jesus's message as his words. Many emphasize the importance of faith, for instance in cleansing ten lepers,[56] Jesus did not say: "My power has saved you," but said:[57][58]

Rise and go; your faith has saved you.

Similarly, in the miracle of walking on water, Apostle Peter learns an important lesson about faith in that as his faith wavers, he begins to sink.[59][60]

Christian authors have discussed the miracles of Jesus at length and assigned specific motives to each miracle. For example, authors Pentecost and Danilson suggest that the miracle of walking on water centered on the relationship of Jesus with his apostles rather than their peril or the miracle itself. In their view, the miracle was specifically designed by Jesus to teach the apostles that when encountering obstacles, they need to rely on their faith in Christ, first and foremost.[61]

Authors Donahue and Harrington argue that the healing of Jairus's daughter teaches that faith, as embodied in the bleeding woman, can exist in seemingly hopeless situations and that through belief, healing can be achieved, in that when the woman is healed, Jesus tells her, "Your faith has healed you".[62]

Liberal Christianity

[edit]Liberal Christians place less emphasis on miraculous events associated with the life of Jesus than on his teachings. The effort to remove superstitious elements from Christian faith dates to intellectual reformist Christians such as Erasmus and the Deists in the 15th–17th centuries.[63] In the 19th century, self-identified liberal Christians sought to elevate Jesus's humane teachings as a standard for a world civilization freed from cultic traditions and traces of pagan belief in the supernatural.[64] The debate over whether a belief in miracles was mere superstition or essential to accepting the divinity of Christ constituted a crisis within the 19th-century church, for which theological compromises were sought.[65]

Attempts to account for miracles through scientific or rational explanation were mocked even at the turn of the 19th–20th century.[66] A belief in the authenticity of miracles was one of five tests established in 1910 by the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America to distinguish true believers from what they saw as false professors of faith such as "educated, 'liberal' Christians."[67]

Contemporary liberal Christians may prefer to read Jesus's miracles as metaphorical narratives for understanding the power of God.[68] Not all theologians with liberal inclinations reject the possibility of miracles, but may reject the polemicism that denial or affirmation entails.[69]

Among other changes, Thomas Jefferson excised all the miracles of Jesus from his Jefferson Bible.

Nonreligious views

[edit]The Scottish philosopher David Hume published an influential essay on miracles in his An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) in which he argued that any evidence for miracles was outweighed by the possibility that those who described them were deceiving themselves or others:

As the violations of truth are more common in the testimony concerning religious miracles, than in that concerning any other matter of fact; this must diminish very much the authority of the former testimony, and make us form a general resolution, never to lend any attention to it, with whatever specious pretence it may be covered.[70]

Historian Will Durant attributes Jesus's miracles to "the natural result of suggestion—of the influence of a strong and confident spirit upon impressionable souls; similar phenomena may be observed any week at Lourdes".[71]

Russian skeptic Kirill Eskov in his Nature-praised work The Gospel of Afranius argues that it was politically prudent for the local Roman administration to strengthen Jesus's influence by spreading rumours about his miracles via active measures and eventually even staging the resurrection itself.

Scholarly views

[edit]Scholars are divided on the interpretation of miracles; some rule them out a priori, while others defend their possibility or reality. There is a consensus that the Historical Jesus was viewed as a miracle-worker during his lifetime. [8] New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman argues that though some historians believe that miracles have happened and others do not, due to the limitations of the sources, it is not possible for historians to affirm or deny them. He states "This is not a problem for only one kind of historian—for atheists or agnostics or Buddhists or Roman Catholics or Baptists or Jews or Muslims; it is a problem for all historians of every stripe."[9][72] According to Michael Licona, among general historians there are some postmodern views of historiography that are open to the investigation of miracles.[73]

According to the Jesus Seminar, Jesus probably cured some sick people,[74] but described Jesus's healings in modern terms, relating them to "psychosomatic maladies." They found six of the nineteen healings to be "probably reliable".[75] Most participants in the Jesus Seminar believe Jesus practiced exorcisms, as Josephus, Philostratus and others wrote about other contemporary exorcists, but do not believe the gospel accounts were accurate reports of specific events or that demons exist.[76] They did not find any of the nature miracles to be historical events.[75]

According to scholar Maurice Casey, it is fair to assume that Jesus was able to cure people affected with psychosomatic disorders, although he believes that the healings were likely due to naturalistic causes and placebo effects.[77] John P. Meier believes that Jesus as healer is as well supported as almost anything about the historical Jesus. In the Gospels, the activity of Jesus as miracle worker looms large in attracting attention to himself and reinforces his eschatological message. Such activity, Meier suggests, might have added to the concern of authorities that culminated in Jesus's death.[78] E.P. Sanders and Géza Vermes also agree that Jesus was indeed a healer and that this helped increase his following among the people of his time.[79][80]

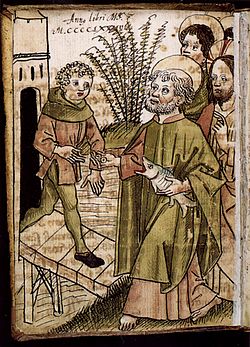

Gallery of miracles

[edit]Cures

[edit]-

The Blind man Bartimaeus in Jericho

Power over demonic spirits

[edit]-

At the Synagogue in Capernaum

Resurrection of the dead

[edit]Relationship with nature

[edit]See also

[edit]- Chronology of Jesus

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Ministry of Jesus

- Miracles of Gautama Buddha

- Miracles of Muhammad

- Parables of Jesus

- International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

References

[edit]- ^ Twelftree (1999) p. 263

- ^ H. Van der Loos, 1965 The Miracles of Jesus, E.J. Brill Press, Netherlands.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "John" pp. 302–310

- ^ "Islamic beliefs include many miracles of healing and of resurrection of the dead." Heribert Busse, 1998 Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, ISBN 1-55876-144-6 p. 114

- ^ Twelftree (1999) p. 19

- ^ Gary R. Habermas, 1996 The historical Jesus: ancient evidence for the life of Christ ISBN 0-89900-732-5 p. 60

- ^ Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Beilby, James K.; Rhodes Eddy, Paul, eds. (2009). "Introduction". The Historical Jesus: Five Views. IVP Academic. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0830838684.

Contrary to previous times, virtually everyone in the field today acknowledges that Jesus was considered by his contemporaries to be an exorcist and a worker of miracles. However, when it comes to historical assessment of the miracles tradition itself, the consensus quickly shatters. Some, following in the footsteps of Bultmann, embrace an explicit methodological naturalism such that the very idea of a miracle is ruled out a priori. Others defend the logical possibility of miracle at the theoretical level, but, in practice, retain a functional methodological naturalism, maintaining that we could never be in possession of the type and/or amount of evidence that would justify a historical judgment in favor of the occurrence of a miracle. Still others, suspicious that an uncompromising methodological naturalism most likely reflects an unwarranted metaphysical naturalism, find such a priori skepticism unwarranted and either remain open to, or even explicitly defend, the historicity of miracles within the Jesus tradition.

- ^ a b c Ehrman, Bart D. (2001). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195124743.

I should emphasize that historians do not have to deny the possibility of miracles or deny that miracles have actually happened in the past. Many historians, for example, committed Christians and observant Jews and practicing Muslims, believe that they have in fact happened. When they think or say this, however, they do so not in the capacity of the historian, but in the capacity of the believer. In the present discussion, I am not taking the position of the believer, nor am I saying that one should or should not take such a position. I am taking the position of the historian, who on the basis of a limited number of problematic sources has to determine to the best of his or her ability what the historical Jesus actually did. As a result, when reconstructing Jesus' activities, I will not be able to affirm or deny the miracles that he is reported to have done...This is not a problem for only one kind of historian—for atheists or agnostics or Buddhists or Roman Catholics or Baptists or Jews or Muslims; it is a problem for all historians of every stripe.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, 2001 Jesus and his contemporaries ISBN 0-391-04118-5 pp. 6–7

- ^ Karl Barth Church dogmatics ISBN 0-567-05089-0 p. 478

- ^ a b The Miracles of Jesus by Craig Blomberg, David Wenham 1986 ISBN 1-85075-009-2 p. 197

- ^ 8:5–13

- ^ 7:1–10

- ^ 4:46–54

- ^ Luke 4:40

- ^ 8:22–26

- ^ 10:46–52

- ^ 20:29–34

- ^ Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1991) p. 133.

- ^ "Luke 18:35–43". Bible.oremus.org. 10 February 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Brent Kinman, Jesus' Entry Into Jerusalem: In the Context of Lukan Theology and the Politics of His Days (Brill, 1995) p. 67.

- ^ 9:1–12

- ^ Jn 5:1–18

- ^ Jn 5:1–18, Mt 12:9–13

- ^ Mark 5:21–43, Matthew 9:18–26 and Luke 8:40–56.

- ^ Mark 1:29–34, Luke 4:38–39 and Matthew 8:14–15

- ^ Mt 12:10, Mk 3:1–3, Lk 6:6–8

- ^ 7:31–37

- ^ Twelftree (1999), p. 283.

- ^ Mark 1:21–28 Luke 4:31–37

- ^ Craig S. Keener, A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1999) p. 282.

- ^ Matthew 8:28–34, Mark 5:1–20, Luke 8:26–39

- ^ Matthew 15:21–28 Mark 7:24–30

- ^ Matthew 17:14–21, Mark 9:14–29, Luke 9:37–49

- ^ Mk 5:21–43

- ^ Mt 9:18–26

- ^ Lk 8:40–56

- ^ Lk 7:11–17

- ^ Jn 11:1–44

- ^ Lk 5:1–11

- ^ Matthew 17:24–27

- ^ "Search | The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ George W. Braswell, 2000 What you need to know about Islam & Muslims ISBN 0-8054-1829-6 p. 112

- ^ a b c Cotter, Wendy (1999). Miracles in Greco-Roman antiquity: a sourcebook. Routledge. pp. 11–12, 37–38, 50–53. ISBN 978-0415118644. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Ferguson, Everett; McHugh, Michael P.; Norris, Frederick W. (1998). Everett Ferguson, Michael P. McHugh, Frederick W. Norris, "Encyclopedia of early Christianity, Volume 1", p. 804. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0815333197. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey; McKnight, Edgar V. (1990). Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard, "Mercer dictionary of the Bible" (Mercer University Press, 1991) p. 61. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0865543737. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Catholic Encyclopedia on Miracles". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1911. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Lockyer, Herbert, 1988 All the Miracles of the Bible ISBN 0-310-28101-6 p. 25

- ^ William Thomas Brande, George William Cox, A dictionary of science, literature, & art London, 1867, also Published by Old Classics on Kindle, 2009, p. 655

- ^ Bernard L. Ramm 1993 An Evangelical Christology ISBN 1-57383-008-9 p. 45

- ^ Author Ken Stocker states that "every single miracle was an act of love": Facts, Faith, and the FAQs by Ken Stocker, Jim Stocker 2006 [ISBN missing] p. 139

- ^ Warren W. Wiersbe 1995 Classic Sermons on the Miracles of Jesus ISBN 0-8254-3999-X p. 132

- ^ 20:30

- ^ The emergence of Christian theology by Eric Francis Osborn 1993 ISBN 0-521-43078-X p. 100

- ^ Lk 17:19

- ^ Berard L. Marthaler 2007 The creed: the apostolic faith in contemporary theology ISBN 0-89622-537-2 p. 220

- ^ Lockyer, Herbert, 1988 All the Miracles of the Bible ISBN 0-310-28101-6 p. 235

- ^ Mt 14:34–36

- ^ Pheme Perkins 1988 Reading the New Testament ISBN 0-8091-2939-6 p. 54

- ^ Dwight Pentecost. The words and works of Jesus Christ. Zondervan, 1980. ISBN 0-310-30940-9, p. 234

- ^ John R. Donahue, Daniel J. Harrington. The Gospel of Mark. Zondervan 1981. ISBN 0-8146-5965-9 p. 182

- ^ Linda Woodhead, "Christianity," in Religions in the Modern World (Routledge, 2002), pp. 186 online and 193.

- ^ Burton L. Mack, The Lost Gospel: The Book of Q and Christian Origins (HarperCollins, 1993), p. 29 online.

- ^ The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion 1805–1900, edited by Gary J. Dorrien (Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), passim, search miracles.

- ^ F. J. Ryan, Protestant Miracles: High Orthodox and Evangelical Authority for the Belief in Divine Interposition in Human Affairs (Stockton, California, 1899), p. 78 online. Full text downloadable.

- ^ Dan P. McAdams, The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 164 online.

- ^ Ann-Marie Brandom, "The Role of Language in Religious Education," in Learning to Teach Religious Education in the Secondary School: A Companion to School Experience (Routledge, 2000), p. 76 online.

- ^ The Making of American Liberal Theology: Idealism, Realism, and Modernity, 1900–1950, edited by Gary J. Dorrien (Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), passim, search miracles, especially p. 413; on Ames, p. 233 online; on Niebuhr, p. 436 online.

- ^ "Modern History Sourcebook: David Hume: On Miracles". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Durant, Will (2002) [2001]. Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7432-2910-4.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0-06-117393-2 p. 175: "We would call a miracle an event that violates the way nature always, or almost always, works ... By now I hope you can see the unavoidable problem historians have with miracles. Historians can establish only what probably happened in the past, but miracles, by their very nature, are always the least probable explanation for what happened"

- ^ Licona, Michael R. (20 November 2014). "Historians and Miracle Claims". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 12 (1–2): 106–129. doi:10.1163/17455197-01202002.

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. p. 566.

- ^ a b Funk 1998, p. 531

- ^ Funk 1998, pp. 530ff

- ^ Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- ^ Meier, John P. (1994). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume II: Mentor, Message, and Miracles. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14033-0.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9059-1.

- ^ Vermes, Geza; Vermès, Géza (1981). Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-1443-0.

- ^ See discussion under § Liberal Christianity.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bersee, Ton (2021). On the Meaning of 'Miracle' in Christianity. An Evaluation of the Current Miracle Debate and a Proposal of a Balanced Hermeneutical Approach. Peeters Publishers, Leuven. ISBN 978-9042943957

- Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. Polebridge Press, San Francisco. ISBN 0060629789

- Kilgallen, John J. (1989). A Brief Commentary on the Gospel of Mark, Paulist Press, ISBN 0809130599

- List of Jesus' Miracles and Biblical References

- Lockyer, Herbert (1988). All the Miracles of the Bible ISBN 0310281016

- Miller, Robert J. Editor (1994). The Complete Gospels, Polebridge Press, ISBN 0060655879

- Murcia, Thierry, Jésus, les miracles en question, Paris, 1999 [ISBN missing] – Jésus, les miracles élucidés par la médecine, Paris, 2003[ISBN missing]

- Omaar, Rageh (2003). The Miracles of Jesus BBC documentary

- Twelftree, Graham H. (1999). Jesus the Miracle Worker: A Historical and Theological Study. IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0830815968.

- Van der Loos, H. (1965). The Miracles of Jesus, E.J. Brill Press, Netherlands[ISBN missing]

KSF

KSF