New Brandeis movement

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

The New Brandeis or neo-Brandeis movement is an antitrust academic and political movement in the United States which argues that excessively centralized private power is dangerous for economical, political and social reasons.[1][2] Initially called hipster antitrust by its detractors, also referred to as the "Columbia school" or "Neo-Progressive antitrust," the movement advocates that United States antitrust law return to a broader concern with private power and its negative effects on market competition, income inequality, consumer rights, unemployment, and wage growth.

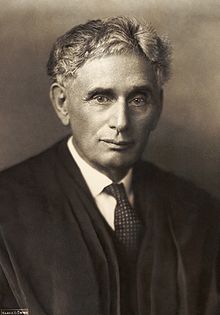

The movement draws inspiration from the anti-monopolist work of Louis Brandeis, an early 20th century United States Supreme Court Justice who called high economic concentration “the Curse of Bigness” and believed monopolies were inherently harmful to the welfare of workers and business innovation.

The New Brandeis movement opposes the school of thought in modern antitrust law that antitrust should center on customer welfare (as generally advocated by the Chicago school of economics). Instead, the New Brandeis movement advocates a broader antimonopoly approach that is concerned with private power, the structure of the economy and market conditions necessary to promote competition.[3][4]

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

| Anti-competitive practices |

|

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

Description

[edit]The New Brandeis movement believes that centralized private power poses a danger to the economic and social conditions of democracy.[5] Neo-Brandeisians believe, for example, that monopoly power is ripe with potential for abuse. They have also argued that dominant tech platforms create high barriers for potential competitors and reduce bargaining power of individual merchants, content providers, and app developers.[6] The movement advocates for market structures that prevent anti-competitive practices and would increase scrutiny of mergers, including vertical mergers. Proponents believe antitrust laws should focus less on short-term price effects of mergers and more on improving the market conditions necessary to promote real competition.[5][6][7]

Support and opposition

[edit]Individuals who have been described as being associated with the movement include Lina Khan, Tim Wu, Jonathan Kanter, and Barry Lynn.[8][9][10] Senators Cory Booker, Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren have been described as allies of the movement,[11][12] and have called on the United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division and Federal Trade Commission to focus their enforcement efforts more on helping workers.[13] The movement has since been the subject of both academic conferences,[14] research papers,[15] and academic journals.[16]

Critics of the New Brandeis movement believe that promoting competition for its own sake causes inefficient producers to stay in business, preferring a litigation approach based on empirical evidence.[17] The term "hipster antitrust" originally began as a Twitter hashtag, and rose to prominence when Senator Orrin Hatch used the term during multiple speeches on the United States Senate floor.[18][19][20][21] Matt Levine of Bloomberg News has written that the term hipster antitrust "appeals to nostalgia for old-fashioned antitrust enforcement".[22] Some proponents of the movement believe the term is pejorative.[23] The term was coined by Konstantin Medvedovsky,[when?][24] an attorney at Dechert, and popularized by disgraced former Federal Trade Commissioner Joshua D. Wright.[25][26]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]As documented by historian Ellis Hawley, the first "NeoBrandeisian" movement arose in the late 1930s.[27] In reaction to the failures of the first New Deal a group headed by Harvard Professor Felix Frankfurter advanced ideas of economic decentralization and renewed antitrust enforcement. These ideas came to be influential during the late 1930s and onward, during the so-called "Second" New Deal. Prominent individuals associated with the movement included Robert H. Jackson, Benjamin V. Cohen, William O. Douglas, and Thurman Arnold.

From World War II until the 1970s, the Brandeisian view that high market concentration leads to anticompetitive behavior was sometimes called the Harvard School of thought because the view was primarily associated with Harvard University, including works by economists Edward Mason, Edward Chamberlain, and Joe Bain. In the early late 1970s, this view fell out of favor as the views of the Chicago School of thought rose, advocating a close attention to the short term effects of mergers on consumer prices.[17]

Development

[edit]Lawrence Lessig wrote "The New Chicago School" article in 1998, challenging directly with analysis of network effects the orthodoxy of antitrust economics during the protracted US v Microsoft litigation of the late 1990s.[citation needed] Tim Wu continued his mentor's work with extensive analysis of net neutrality from 2003, to which Yochai Benkler and Nicholas Economides, both then at NYU, contributed.[citation needed] Continuing in the late 2010s,[28] the movement takes inspiration from former US Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, who was a prominent anti-monopolist.[29][30] Brandeis believed that antitrust action should prevent any one company from maintaining too much power over the economy because monopolies were harmful to innovation, business vitality, and the welfare of workers.[5][17] He described "The Curse of Bigness," believing that large profitable firms use their money to influence politics and create further consolidation and dominance, once stating, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”[17][31]

In the 2010s, the New Brandeis theory was popularized by legal scholars Lina Khan and Tim Wu, both of Columbia University. Khan published an article about the negative effects of monopoly power by the company Amazon.[17] The theory would heighten scrutiny of large company mergers.[32]

Wu published The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Golden Age in 2018, which criticized antitrust's drift from its historic origins, introduced Brandeis' life and ideals, and advocated a return a more decentralized economy. [33] In 2019 Khan, Wu and others released a "Utah Statement" written at anti-monopoly conference meant as a codification of the movements' main principles.[34][35]

Biden administration

[edit]The movement was perceived to grow in influence during the Biden administration, as compared to the prior Trump and Obama presidencies.[8][36] In 2020, the American Economic Liberties Project (AELP) was founded by several neo-Brandeisians to support regulatory efforts and research, led by Sarah Miller.[37][38] The Wall Street Journal described the movement as "a new generation of trustbusters" in 2021, arguing that it represented a shift away from a singular focus on perceived consumer welfare that began with the Reagan administration and the ideas of Robert Bork.[6]

In 2021, the White House appointed Tim Wu, a prominent member of the movement at Columbia, to serve as special assistant to the President for Competition and Technology policy.[39] The President in July 2021 signed a new Executive Order of Competition, which called for a reinvigoration of competition policy across government.[40] Biden later nominated Jonathan Kanter, a neo-Brandeisian, to serve as assistant attorney general in the Department of Justice Antitrust Division.[41][42] Kanter was confirmed by the United States Senate by a vote of 68–29 and took office in November 2021.[43][44] Biden also nominated Lina Khan to be Chair of the Federal Trade Commission.[45][46] On June 15, 2021, her nomination was confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 69 to 28.[47] Khan was confirmed with bipartisan support.[48]

Since the appointment of Neo-Brandeisian "troika" of Tim Wu, Lina Khan, and Jonathan Kanter,[49] the U.S. government has reformed the review of mergers,[50] reinvigorated pro-competitive rulemakings in non-antitrust agencies,[51] blocked several high profile mergers like JetBlue/Spirit[52], Penguin/S&S[53][54] and Kroger/Albertsons[55] and taken tech platform Google to trial in the first major monopolization case of the 21st century.[56] The movement has also experienced some setbacks, including at least one loss against Facebook in court.[57]

References

[edit]- ^ Wu, Timothy (2018). The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. New York: Columbia Global Reports. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ "The New Brandeis Ideology (mid 2010s – Present): On the Dangers of Monopoly Power". Unbuilt Labs. 2021-01-06. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ Khan, Lina (2018-03-01). "The New Brandeis Movement: America's Antimonopoly Debate". Journal of European Competition Law & Practice. 9 (3): 131–132. doi:10.1093/jeclap/lpy020. ISSN 2041-7764.

- ^ "What Is 'Hipster Antitrust?'". Mercatus Center. 2018-10-18. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ a b c "What more should antitrust be doing?". The Economist. 2020-08-06. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ a b c Ip, Greg (2021-07-07). "Antitrust's New Mission: Preserving Democracy, Not Efficiency". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Khan, Lina M. "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox". www.yalelawjournal.org. Archived from the original on 2020-12-30. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ a b Sammon, Alexander; Dayen, David (2021-07-21). "The New Brandeis Movement Has Its Moment". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Nylen, Leah (8 July 2021). "Biden launches assault on monopolies". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 2021-07-08. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "The New Brandeis Movement: America's Anti-Monopoly Debate". Open Markets Institute. 13 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "US: 'Hipster Antitrust' ally joins The Senate Judiciary Committee | Competition Policy International". www.competitionpolicyinternational.com. 6 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Kolhatkar, Sheelah (2021-11-25). "Lina Khan's Battle to Rein in Big Tech". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ "Booker calls on antitrust regulators to start paying attention to workers". Vox. Archived from the original on 2018-03-18. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "George Mason Law Review's 21st Annual Antitrust Symposium – Law & Economics Center". masonlec.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Daly, Angela (2017-08-02). "Beyond 'Hipster Antitrust': A Critical Perspective on the European Commission's Google Decision". SSRN 3012437.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Antitrust Chronicle – Hipster Antitrust | Competition Policy International". www.competitionpolicyinternational.com. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ a b c d e Eeckhout, Jan (June 2021). The Profit Paradox: How Thriving Firms Threaten the Future of Work. Princeton University Press. pp. 246–248. ISBN 978-0-691-21447-4. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ "Hatch Speaks on Growing Controversy Over Antitrust Law in the Tech Sector - Press Releases - United States Senator Orrin Hatch". www.hatch.senate.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-02-08. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Senator Leans Into Avocado Toast Trend to Make a Point". Time. Archived from the original on 2018-03-06. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-08-07). "Orrin Hatch, the Original Antitrust Hipster, Turns on His Own Kind". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 2018-02-22. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Hatch Speaks Again on 'Hipster Antitrust,' Delrahim Confirmation". Orrin Hatch Official site. 2018-02-20. Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ Levine, Matt (2018-09-10). "Keep Your Bitcoins in the Bank". www.bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Streitfeld, David (7 September 2018). "Amazon's Antitrust Antagonist Has a Breakthrough Idea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Medvedovsky, Kostya (2017-06-19). "Antitrust hipsterism. Everything old is cool again". @kmedved. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Do Not Mistake Orrin Hatch for #HipsterAntitrust". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ "Hipster antitrust hits the Senate: The Tipline for 4 August 2017". globalcompetitionreview.com. 2017-08-04. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- ^ Hawley, Ellis (1966). The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Khan, Lina (2018-03-01). "The New Brandeis Movement: America's Antimonopoly Debate". Journal of European Competition Law & Practice. 9 (3): 131–132. doi:10.1093/jeclap/lpy020. ISSN 2041-7764.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-04-04). "This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ De La Cruz, Peter. "The Antitrust Pendulum Swings to the Populist Pole". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ Dayen, David (2017-04-04). "This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Webb, Patterson Belknap; Walter-Warner, Tyler LLP-Jake; Hatch, Jonathan H. (2018-11-08). "A Brief Overview of the "New Brandeis" School of Antitrust Law". Lexology. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ Wu, Timothy (2018). The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. New York: Columbia Global Reports. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ Din, Benjamin (21 June 2021). "The dawn of the age of Khan". Politico. Retrieved 2022-08-06.

- ^ "The Utah Statement". 19 November 2019.

- ^ Nylen, Leah (27 December 2021). "The new rules of Monopoly". Politico. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ Scola, Nancy (21 April 2023). "Washington's Angriest Progressive Is Winning Over Conservatives – and Baffling Old Allies". Politico. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ McCabe, David (2020-02-11). "She Wants to Break Up Big Everything". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (5 March 2021). "Big Tech critic Tim Wu joins Biden administration to work on competition policy". CNBC. Retrieved 2022-08-06.

- ^ "Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy". 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Biden taps progressives' favorite for DOJ antitrust post". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 2021-07-20. Retrieved 2021-07-20.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (2021-09-24). "Nine former DOJ antitrust chiefs urge Senate to confirm Jonathan Kanter as antitrust head". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2021-10-05. Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ "On the Nomination (Confirmation: Jonathan Kanter, of Maryland, to be an Assistant Attorney General)". US Senate. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Senate confirms Google critic Kanter to head Justice Dept Antitrust Division". Reuters. 2021-11-17. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ Kelly, Makena (22 March 2021). "Biden to nominate tech antitrust pioneer Lina Khan for FTC commissioner". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "President Biden Announces his Intent to Nominate Lina Khan for Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission". The White House. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (2021-06-15). "Tech antitrust pioneer Lina Khan confirmed as FTC commissioner". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 2021-06-15. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (30 June 2021). "Amazon says new FTC chair shouldn't regulate it because she's too mean". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Wu, Khan and Kanter: Biden's antitrust troika falls into place". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Antitrust Division | 2023 Merger Guidelines | United States Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the (2022-08-16). "FDA Finalizes Historic Rule Enabling Access to Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids for Millions of Americans". FDA. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Josephs, Leslie (2024-01-16). "Judge blocks JetBlue-Spirit merger after DOJ's antitrust challenge". CNBC. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Judge blocks Penguin Random House-Simon & Schuster merger". CNBC. 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "United States v. BERTELSMANN SE & CO. KGAA, 1:21-cv-02886". Retrieved 2024-06-22.

- ^ "Statement on FTC Victory Securing Halt to Kroger, Albertsons Grocery Merger". FTC. 10 December 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ McCabe, David; Kang, Cecilia (2023-09-06). "In Its First Monopoly Trial of Modern Internet Era, U.S. Sets Sights on Google". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (2023-02-01). "Meta acquisition of Within reportedly approved by court in loss for FTC". CNBC. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

KSF

KSF