New Zealand

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 79 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 79 min

New Zealand Aotearoa (Māori) | |

|---|---|

| Anthems: God Defend New Zealand (Māori: Aotearoa) God Save the King[n 1] (Māori: Me tohu e te Atua) | |

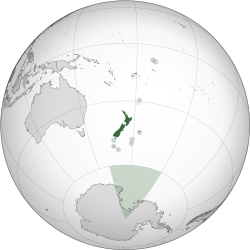

Location of New Zealand, including outlying islands, its territorial claim in the Antarctic, and Tokelau | |

| Capital | Wellington 41°18′S 174°47′E / 41.300°S 174.783°E |

| Largest city | Auckland |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2023)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Cindy Kiro | |

| Christopher Luxon | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Stages of independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 6 February 1840 | |

| 7 May 1856 | |

• Dominion | 26 September 1907 |

| 25 November 1947 | |

| 1 January 1987 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 263,310[7] km2 (101,660 sq mi) (75th) |

• Water (%) | 1.6[n 5] |

| Population | |

• August 2025 estimate | |

• 2023 census | |

• Density | 19.7/km2 (51.0/sq mi) (204th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2023) | very high (17th) |

| Currency | New Zealand dollar ($) (NZD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST[n 6]) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT[n 7]) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy[17] |

| Calling code | +64 |

| ISO 3166 code | NZ |

| Internet TLD | .nz |

New Zealand (Māori: Aotearoa) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui) and the South Island (Te Waipounamu)—and over 600 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island country by area and lies east of Australia across the Tasman Sea and south of the islands of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga. The country's varied topography and sharp mountain peaks, including the Southern Alps (Kā Tiritiri o te Moana), owe much to tectonic uplift and volcanic eruptions. New Zealand's capital city is Wellington, and its most populous city is Auckland.

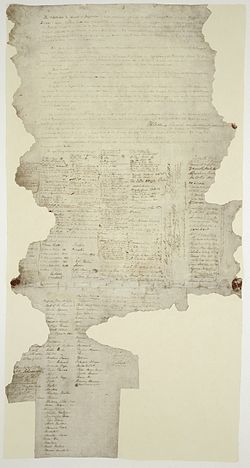

The islands of New Zealand were the last large habitable land to be settled by humans. Between about 1280 and 1350, Polynesians began to settle in the islands and subsequently developed a distinctive Māori culture. In 1642, the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman became the first European to sight and record New Zealand. In 1769 the British explorer Captain James Cook became the first European to set foot on and map New Zealand. In 1840, representatives of the United Kingdom and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi which paved the way for Britain's declaration of sovereignty later that year and the establishment of the Crown Colony of New Zealand in 1841. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land. New Zealand became a dominion in 1907; it gained full statutory independence in 1947, retaining the monarch as head of state. Today, the majority of New Zealand's population of around 5.3 million is of European descent; the indigenous Māori are the largest minority, followed by Asians and Pasifika. Reflecting this, New Zealand's culture is mainly derived from Māori and early British settlers but has recently broadened from increased immigration. The official languages are English, Māori, and New Zealand Sign Language, with the local dialect of English being dominant.

A developed country, New Zealand was the first to introduce a minimum wage and give women the right to vote. It ranks very highly in international measures of quality of life and human rights and has one of the lowest levels of perceived corruption in the world. It retains visible levels of inequality, including structural disparities between its Māori and European populations. New Zealand underwent major economic changes during the 1980s, which transformed it from a protectionist to a liberalised free-trade economy. The service sector dominates the country's economy, followed by the industrial sector, and agriculture; international tourism is also a significant source of revenue. New Zealand and Australia have a strong relationship and are considered to share a strong Trans-Tasman identity, stemming from centuries of British colonisation. The country is part of multiple international organizations and forums.

Nationally, legislative authority is vested in an elected, unicameral Parliament, while executive political power is exercised by the Government, led by the prime minister, currently Christopher Luxon. Charles III is the country's king and is represented by the governor-general, Cindy Kiro. New Zealand is organised into 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities for local government purposes. The Realm of New Zealand also includes Tokelau (a dependent territory); the Cook Islands and Niue (self-governing states in free association with New Zealand); and the Ross Dependency, which is New Zealand's territorial claim in Antarctica.

Etymology

[edit]

The first European visitor to New Zealand, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, named the islands Staten Land, believing they were part of the Staten Landt that Jacob Le Maire had sighted off the southern end of South America.[18][19] The next year, in 1643, Hendrik Brouwer proved that the South American land was just a small island, and Dutch cartographers subsequently renamed Tasman's discovery Nova Zeelandia from Latin, after the Dutch province of Zeeland.[18][20] This name was later anglicised to New Zealand.[21][22]

This was written as Nu Tireni in the Māori language (spelled Nu Tirani in Te Tiriti o Waitangi). In 1834, a document written in Māori and entitled "He Wakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni" was translated into English and became the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand. It was prepared by Te W(h)akaminenga o Nga Rangatiratanga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tireni, the United Tribes of New Zealand, and a copy was sent to King William IV who had already acknowledged the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand, and who recognised the declaration in a letter from Lord Glenelg.[23][24]

Aotearoa (pronounced [aɔˈtɛaɾɔa] in Māori and /ˌaʊtɛəˈroʊ.ə/ in English; often translated as 'land of the long white cloud')[25] is the current Māori name for New Zealand. It is unknown whether Māori had a name for the whole country before the arrival of Europeans; Aotearoa originally referred to just the North Island.[26] Māori had several traditional names for the two main islands, including Te Ika-a-Māui ('the fish of Māui') for the North Island and Te Waipounamu ('the waters of greenstone') or Te Waka o Aoraki ('the canoe of Aoraki') for the South Island.[27] Early European maps labelled the islands North (North Island), Middle (South Island), and South (Stewart Island / Rakiura).[28]

In 1830, mapmakers began to use "North" and "South" on their maps to distinguish the two largest islands, and by 1907, this was the accepted norm.[22] The New Zealand Geographic Board discovered in 2009 that the names of the North Island and South Island had never been formalised, and names and alternative names were formalised in 2013. This set the names as North Island or Te Ika-a-Māui, and South Island or Te Waipounamu.[29] For each island, either its English or Māori name can be used, or both can be used together.[29] Similarly the Māori and English names for the whole country are sometimes used together (Aotearoa New Zealand);[30][31] however, this has no official recognition.[32]

History

[edit]

The first people to reach New Zealand were Polynesians in ocean going waka, who are believed to have arrived in several waves, approximately between 1280 and 1350 CE. According to most Māori oral traditions, the islands were first discovered by the semi-legendary explorer Kupe while in pursuit of a giant octopus.[36] These traditions held that Kupe was then followed by a great fleet of settlers, who set out from Hawaiki in eastern Polynesia in around 1350.[37] The existence of a single great fleet which settled New Zealand has since been superseded by the belief that the majority of settlement was a planned and deliberate event that occurred over several decades.[38][39][40][41][42]

The exact date of this settlement is unclear, with recent sources favouring settlement in the 14th century. While mitochondrial DNA variability within Māori populations suggest that New Zealand was first settled between 1250 and 1300,[27][43][44] no human remains, artefacts or structures can be reliably dated to earlier than the Kaharoa eruption of Mount Tarawera in around 1314 CE.[45] This scenario is also consistent with a debated third line of oral evidence,[46] traditional genealogies (whakapapa) which point to around 1350 as a probable arrival date for several of the migratory waka (canoes) from which many Māori trace their descent.[47][48] Some Māori later migrated to the Chatham Islands where they developed their distinct Moriori culture;[49] a later 1835 invasion by Māori iwi resulted in the massacre and virtual extinction of the Moriori.[50]

In a hostile 1642 encounter between Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri and Dutch explorer Abel Tasman's crew,[51][52] four of Tasman's crew members were killed, and at least one Māori was hit by canister shot.[53] Europeans did not revisit New Zealand until 1769, when British explorer James Cook mapped almost the entire coastline.[52] Following Cook, New Zealand was visited by numerous European and North American whaling, sealing, and trading ships. They traded European food, metal tools, weapons, and other goods for timber, Māori food, artefacts, and water.[54]

The introduction of the potato and the musket transformed Māori agriculture and warfare. Potatoes provided a reliable food surplus, which enabled longer and more sustained military campaigns.[55] The resulting intertribal Musket Wars encompassed over 600 battles between 1801 and 1840, killing 30,000–40,000 Māori.[56] From the early 19th century, Christian missionaries began to settle New Zealand, eventually converting most of the Māori population.[57] The Māori population declined to around 40% of its pre-contact level during the 19th century; introduced diseases were the major factor.[58]

The British Government appointed James Busby as British Resident to New Zealand in 1832.[59] His duties, given to him by Governor Bourke in Sydney, were to protect settlers and traders "of good standing", prevent "outrages" against Māori, and apprehend escaped convicts.[59][60] In 1835, following an announcement of impending French settlement by Charles de Thierry, the nebulous United Tribes of New Zealand sent a Declaration of Independence to King William IV of the United Kingdom asking for protection.[59] Ongoing unrest, the proposed settlement of New Zealand by the New Zealand Company (which had already sent its first ship of surveyors to buy land from Māori) and the dubious legal standing of the Declaration of Independence prompted the Colonial Office to send Captain William Hobson to claim sovereignty for the United Kingdom and negotiate a treaty with the Māori.[61] The Treaty of Waitangi was first signed in the Bay of Islands on 6 February 1840.[62] In response to the New Zealand Company's attempts to establish an independent settlement in Wellington,[63][64] Hobson declared British sovereignty over all of New Zealand on 21 May 1840, even though copies of the treaty were still circulating throughout the country for Māori to sign.[65] With the signing of the treaty and declaration of sovereignty, the number of immigrants, particularly from the United Kingdom, began to increase.[66]

New Zealand was administered as a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales until becoming a separate Crown colony, the Colony of New Zealand, on 3 May 1841.[67][68] Armed conflict began between the colonial government and Māori in 1843 with the Wairau Affray over land and disagreements over sovereignty. These conflicts, mainly in the North Island, saw thousands of imperial troops and the Royal Navy come to New Zealand and became known as the New Zealand Wars. Following these armed conflicts, large areas of Māori land were confiscated by the government to meet settler demands.[69]

The colony gained a representative government in 1852, and the first Parliament met in 1854.[70] In 1856 the colony effectively became self-governing, gaining responsibility over all domestic matters, except native policy, which was granted in the mid-1860s.[70] Following concerns that the South Island might form a separate colony, premier Alfred Domett moved a resolution to transfer the capital from Auckland to a locality near Cook Strait.[71][72] Wellington was chosen for its central location, with Parliament officially sitting there for the first time in 1865.[73]

In 1886, New Zealand annexed the volcanic Kermadec Islands, about 1,000 km (620 mi) northeast of Auckland. Since 1937, the islands are uninhabited except for about six people at Raoul Island station. These islands put the northern border of New Zealand at 29 degrees South latitude.[74] After the 1982 UNCLOS, the islands contributed significantly to New Zealand's exclusive economic zone.[75]

In 1891, the Liberal Party came to power as the first organised political party.[76] The Liberal Government, led by Richard Seddon for most of its period in office,[77] passed many important social and economic measures. In 1893, New Zealand was the first nation in the world to grant all women the right to vote[76] and pioneered the adoption of compulsory arbitration between employers and unions in 1894.[78] The Liberals also guaranteed a minimum wage in 1894, a world first.[79]

In 1907, at the request of the New Zealand Parliament, King Edward VII proclaimed New Zealand a Dominion within the British Empire,[80] reflecting its self-governing status.[81] In 1947, New Zealand adopted the Statute of Westminster, confirming that the British Parliament could no longer legislate for the country without its consent. The British government's residual legislative powers were later removed by the Constitution Act 1986, and final rights of appeal to British courts were abolished in 2003.[70]

Early in the 20th century, New Zealand was involved in world affairs, fighting in the First and Second World Wars[82] and suffering through the Great Depression.[83] The depression led to the election of the first Labour Government and the establishment of a comprehensive welfare state and a protectionist economy.[84] New Zealand experienced increasing prosperity following the Second World War,[85] and Māori began to leave their traditional rural life and move to the cities in search of work.[86] A Māori protest movement developed, which criticised Eurocentrism and worked for greater recognition of Māori culture and of the Treaty of Waitangi.[87] In 1975, a Waitangi Tribunal was set up to investigate alleged breaches of the Treaty, and it was enabled to investigate historic grievances in 1985.[62] The government has negotiated settlements of these grievances with many iwi,[88] although Māori claims to the foreshore and seabed proved controversial in the 2000s.[89][90]

Geography and environment

[edit]

New Zealand is located near the centre of the water hemisphere and is made up of two main islands and more than 700 smaller islands.[91] The two main islands (the North Island, or Te Ika-a-Māui, and the South Island, or Te Waipounamu) are separated by Cook Strait, 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide at its narrowest point.[92] Besides the North and South Islands, the five largest inhabited islands are Stewart Island (across the Foveaux Strait), Chatham Island, Great Barrier Island (in the Hauraki Gulf),[93] D'Urville Island (in the Marlborough Sounds)[94] and Waiheke Island (about 22 km (14 mi) from central Auckland).[95]

New Zealand is long and narrow—over 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) along its north-north-east axis with a maximum width of 400 kilometres (250 mi)[96]—with about 15,000 km (9,300 mi) of coastline[97] and a total land area of 268,000 square kilometres (103,500 sq mi).[98] Because of its far-flung outlying islands and long coastline, the country has extensive marine resources. Its exclusive economic zone is one of the largest in the world, covering more than 15 times its land area.[99]

The South Island is the largest landmass of New Zealand. It is divided along its length by the Southern Alps.[100] There are 18 peaks over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), the highest of which is Aoraki / Mount Cook at 3,724 metres (12,218 ft).[101] Fiordland's steep mountains and deep fiords record the extensive ice age glaciation of this southwestern corner of the South Island.[102] The North Island is less mountainous but is marked by volcanism.[103] The highly active Taupō Volcanic Zone has formed a large volcanic plateau, punctuated by the North Island's highest mountain, Mount Ruapehu (2,797 metres (9,177 ft)). The plateau also hosts the country's largest lake, Lake Taupō,[91] nestled in the caldera of one of the world's most active supervolcanoes.[104] New Zealand is prone to earthquakes.

The country owes its varied topography, and perhaps even its emergence above the waves, to the dynamic boundary it straddles between the Pacific and Indo-Australian Plates.[105] New Zealand is part of Zealandia, a microcontinent nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gondwanan supercontinent.[106][107] About 25 million years ago, a shift in plate tectonic movements began to contort and crumple the region. This is now most evident in the Southern Alps, formed by compression of the crust beside the Alpine Fault. Elsewhere, the plate boundary involves the subduction of one plate under the other, producing the Puysegur Trench to the south, the Hikurangi Trough east of the North Island, and the Kermadec and Tonga Trenches[108] further north.[105]

New Zealand, together with Australia, is part of a wider region known as Australasia.[109] It also forms the southwestern extremity of the geographic and ethnographic region called Polynesia.[110] Oceania is a wider region encompassing the Australian continent, New Zealand, and various island countries in the Pacific Ocean that are not included in the seven-continent model.[111]

Climate

[edit]New Zealand's climate is predominantly temperate maritime (Köppen: Cfb), with mean annual temperatures ranging from 10 °C (50 °F) in the south to 16 °C (61 °F) in the north.[112] Historical maxima and minima are 42.4 °C (108.32 °F) in Rangiora, Canterbury and −25.6 °C (−14.08 °F) in Ranfurly, Otago.[113] Conditions vary sharply across regions, from extremely wet on the West Coast of the South Island to semi-arid in Central Otago and the Mackenzie Basin of inland Canterbury and subtropical in Northland.[114][115]

Of the seven largest cities, Christchurch is the driest, receiving on average only 618 millimetres (24.3 in) of rain per year. Wellington the wettest, receiving almost twice that amount.[116] Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch all receive a yearly average of more than 2,000 hours of sunshine. The southern and southwestern parts of the South Island have a cooler and cloudier climate, with around 1,400–1,600 hours. The northern and northeastern parts of the South Island are the sunniest areas of the country and receive about 2,400–2,500 hours.[117]

The general snow season is early June until early October, though cold snaps can occur outside this season.[118] Snowfall is common in the eastern and southern parts of the South Island and mountain areas across the country.[112]

| Location | January high °C (°F) |

January low °C (°F) |

July high °C (°F) |

July low °C (°F) |

Annual rainfall mm (in) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auckland | 23 (73) | 15 (59) | 15 (59) | 8 (46) | 1,212 (47.7) |

| Wellington | 20 (68) | 14 (57) | 11 (52) | 6 (43) | 1,207 (47.5) |

| Hokitika | 20 (68) | 12 (54) | 12 (54) | 3 (37) | 2,901 (114.2) |

| Christchurch | 23 (73) | 12 (54) | 11 (52) | 2 (36) | 618 (24.3) |

| Alexandra | 25 (77) | 11 (52) | 8 (46) | −2 (28) | 359 (14.1) |

Biodiversity

[edit]

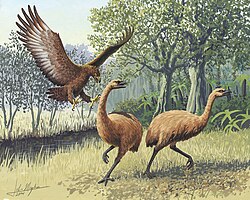

New Zealand's geographic isolation for 80 million years[120] and island biogeography has influenced evolution of the country's species of animals, fungi and plants. Physical isolation has caused biological isolation, resulting in a dynamic evolutionary ecology with examples of distinctive plants and animals as well as populations of widespread species.[121][122] The flora and fauna of New Zealand were originally thought to have originated from New Zealand's fragmentation off from Gondwana, however more recent evidence postulates species resulted from dispersal.[123]

About 82% of New Zealand's indigenous vascular plants are endemic, covering 1,944 species across 65 genera.[124][125] The number of fungi recorded from New Zealand, including lichen-forming species, is not known, nor is the proportion of those fungi which are endemic, but one estimate suggests there are about 2,300 species of lichen-forming fungi in New Zealand[124] and 40% of these are endemic.[126] The two main types of forest are those dominated by broadleaf trees with emergent podocarps, or by southern beech in cooler climates.[127] The remaining vegetation types consist of grasslands, the majority of which are tussock.[128]

Before the arrival of humans, an estimated 80% of the land was covered in forest, with only high alpine, wet, infertile and volcanic areas without trees.[129] Massive deforestation occurred after humans arrived, with around half the forest cover lost to fire after Polynesian settlement.[130] Much of the remaining forest fell after European settlement, being logged or cleared to make room for pastoral farming, leaving forest occupying only 23% of the land in 1997.[131]

The forests were dominated by birds, and the lack of mammalian predators led to some like the kiwi, kākāpō, weka and takahē evolving flightlessness.[132] The arrival of humans, associated changes to habitat, and the introduction of rats, ferrets and other mammals led to the extinction of many bird species, including large birds like the moa and Haast's eagle.[133][134]

Other indigenous animals are represented by reptiles (tuatara, skinks and geckos), frogs,[135] such as the protected endangered Hamilton's Frog, spiders,[136] insects (wētā),[137] and snails.[138] Some, such as the tuatara, are so unique that they have been called living fossils.[139] Three species of bats (one since extinct) were the only sign of native land mammals in New Zealand until the 2006 discovery of bones from a unique, mouse-sized land mammal at least 16 million years old.[140][141] Marine mammals are abundant, with almost half the world's cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) and large numbers of fur seals reported in New Zealand waters.[142] Many seabirds breed in New Zealand, a third of them unique to the country.[143] More penguin species are found in New Zealand than in any other country, with 13 of the world's 18 penguin species.[144]

Since human arrival, almost half of the country's vertebrate species have become extinct, including at least fifty-one birds, three frogs, three lizards, one freshwater fish, and one bat. Others are endangered or have had their range severely reduced.[133] New Zealand conservationists have pioneered several methods to help threatened wildlife recover, including island sanctuaries, pest control, wildlife translocation, fostering, and ecological restoration of islands and other protected areas.[145][146][147][148]

Government and politics

[edit]New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy,[149] although its constitution is not codified.[150] Charles III is the King of New Zealand[151] and thus the head of state.[152] The king is represented by the governor-general, whom he appoints on the advice of the prime minister.[153] The governor-general can exercise the Crown's prerogative powers, such as reviewing cases of injustice and making appointments of ministers, ambassadors, and other key public officials,[154] and in rare situations, the reserve powers (e.g. the power to dissolve Parliament or refuse the royal assent of a bill into law).[155] The powers of the monarch and the governor-general are limited by constitutional constraints, and they cannot normally be exercised without the advice of ministers.[155]

The New Zealand Parliament holds legislative power and consists of the king and the House of Representatives.[156] It also included an upper house, the Legislative Council, until this was abolished in 1950.[156] The supremacy of parliament over the Crown and other government institutions was established in England by the Bill of Rights 1689 and has been ratified as law in New Zealand.[156] The House of Representatives is democratically elected, and a government is formed from the party or coalition with the majority of seats. If no majority is formed, a minority government can be formed if support from other parties during confidence and supply votes is assured.[156] The governor-general appoints ministers under advice from the prime minister, who is by convention the parliamentary leader of the governing party or coalition.[157] Cabinet, formed by ministers and led by the prime minister, is the highest policy-making body in government and responsible for deciding significant government actions.[158] Members of Cabinet make major decisions collectively and are therefore collectively responsible for the consequences of these decisions.[159] The 42nd and current prime minister, since 27 November 2023, is Christopher Luxon.[160]

A parliamentary general election must be called no later than three years after the previous election.[161] Almost all general elections between 1853 and 1993 were held under the first-past-the-post voting system.[162] Since the 1996 election, a form of proportional representation called mixed-member proportional (MMP) has been used.[150] Under the MMP system, each person has two votes; one is for a candidate standing in the voter's electorate, and the other is for a party. Based on the 2018 census data, there are 72 electorates (which include seven Māori electorates in which only Māori can optionally vote),[163] and the remaining 48 of the 120 seats are assigned so that representation in Parliament reflects the party vote, with the threshold that a party must win at least one electorate or 5% of the total party vote before it is eligible for a seat.[164] Elections since the 1930s have been dominated by two political parties, National and Labour. More parties have been represented in Parliament since the introduction of MMP.[165]

New Zealand's judiciary, headed by the chief justice,[166] includes the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, the High Court, and subordinate courts.[167] Judges and judicial officers are appointed non-politically and under strict rules regarding tenure to help maintain judicial independence.[150] This theoretically allows the judiciary to interpret the law based solely on the legislation enacted by Parliament without other influences on their decisions.[168]

New Zealand is identified as one of the world's most stable and well-governed states.[169] As of 2023,[update] the country is ranked second in the strength of its democratic institutions,[170] and third in government transparency and lack of corruption.[171] LGBT rights in the nation are also recognised as among the most tolerant in Oceania.[172] New Zealand ranks highly for civic participation in the political process, with 82% voter turnout during recent general elections, compared to an OECD average of 69%.[173] However, this is untrue for local council elections; a historically low 36% of eligible New Zealanders voted in the 2022 local elections, compared with an already low 42% turnout in 2019.[174][175][176] A 2017 human rights report by the United States Department of State noted that the New Zealand government generally respected the rights of individuals, but voiced concerns regarding the social status of the Māori population.[177] In terms of structural discrimination, the New Zealand Human Rights Commission has asserted that there is strong, consistent evidence that it is a real and ongoing socioeconomic issue.[178] One example of structural inequality in New Zealand can be seen in the criminal justice system. According to the Ministry of Justice, Māori are overrepresented, comprising 45% of New Zealanders convicted of crimes and 53% of those imprisoned, while only being 16.5% of the population.[179][180]

Regions and external territories

[edit]

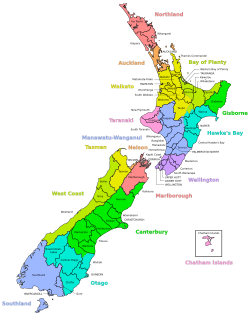

The early European settlers divided New Zealand into provinces, which had a degree of autonomy.[181] Because of financial pressures and the desire to consolidate railways, education, land sales, and other policies, government was centralised and the provinces were abolished in 1876.[182] The provinces are remembered in regional public holidays[183] and sporting rivalries.[184]

Since 1876, various councils have administered local areas under legislation determined by the central government.[181][185] In 1989, the government reorganised local government into the current two-tier structure of regional councils and territorial authorities.[186] The 249 municipalities[186] that existed in 1975 have now been consolidated into 67 territorial authorities and 11 regional councils.[187] The regional councils' role is to regulate "the natural environment with particular emphasis on resource management",[186] while territorial authorities are responsible for sewage, water, local roads, building consents, and other local matters.[188][189] Five of the territorial councils are unitary authorities and also act as regional councils.[189] The territorial authorities consist of 13 city councils, 53 district councils, and the Chatham Islands Council. While officially the Chatham Islands Council is not a unitary authority, it undertakes many functions of a regional council.[190]

The Realm of New Zealand, one of 15 Commonwealth realms,[191] is the entire area over which the king or queen of New Zealand is sovereign and comprises New Zealand, Tokelau, the Ross Dependency, the Cook Islands, and Niue.[149] The Cook Islands and Niue are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand.[192][193] The New Zealand Parliament cannot pass legislation for these countries, but with their consent can act on behalf of them in foreign affairs and defence. Tokelau is classified as a non-self-governing territory, but is administered by a council of three elders (one from each Tokelauan atoll).[194] The Ross Dependency is New Zealand's territorial claim in Antarctica, where it operates the Scott Base research facility.[195] New Zealand nationality law treats all parts of the realm equally, so most people born in New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, and the Ross Dependency are New Zealand citizens.[196][n 8]

Foreign relations

[edit]

During the period of the New Zealand colony, Britain was responsible for external trade and foreign relations.[198] The 1923 and 1926 Imperial Conferences decided that New Zealand should be allowed to negotiate its own political treaties, and the first commercial treaty was ratified in 1928 with Japan. On 3 September 1939, New Zealand allied itself with Britain and declared war on Germany with Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage proclaiming, "Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand".[199]

In 1951, the United Kingdom became increasingly focused on its European interests,[200] while New Zealand joined Australia and the United States in the ANZUS security treaty.[201] The influence of the United States on New Zealand weakened following protests over the Vietnam War,[202] the refusal of the United States to admonish France after the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior,[203] disagreements over environmental and agricultural trade issues, and New Zealand's nuclear-free policy.[204][205] Despite the United States's suspension of ANZUS obligations, the treaty remained in effect between New Zealand and Australia, whose foreign policy has followed a similar historical trend.[206] Close political contact is maintained between the two countries, with free trade agreements and travel arrangements that allow citizens to visit, live and work in both countries without restrictions.[207] In 2013[update] there were about 650,000 New Zealand citizens living in Australia, which is equivalent to 15% of the population of New Zealand.[208]

New Zealand has a strong presence among the Pacific Island countries, and enjoys strong diplomatic relations with Samoa, Fiji, and Tonga, and among smaller nations.[209] A large proportion of New Zealand's aid goes to these countries, and many Pacific people migrate to New Zealand for employment. The increase of this since the 1960s led to the formation of the Pasifika New Zealander pan-ethnic group, the fourth-largest ethnic grouping in the country.[210][211] Permanent migration is regulated under the 1970 Samoan Quota Scheme and the 2002 Pacific Access Category, which allow up to 1,100 Samoan nationals and up to 750 other Pacific Islanders respectively to become permanent New Zealand residents each year. A seasonal workers scheme for temporary migration was introduced in 2007, and in 2009 about 8,000 Pacific Islanders were employed under it.[212] New Zealand is involved in the Pacific Islands Forum, the Pacific Community, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum (including the East Asia Summit).[207] New Zealand has been described as a middle power in the Asia-Pacific region,[213] and an emerging power.[214][215] The country is a member of the United Nations,[216] the Commonwealth of Nations[217] and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),[218] and participates in the Five Power Defence Arrangements.[219]

Today, New Zealand enjoys particularly close relations with the United States and is one of its major non-NATO allies,[220] as well as with Australia, with a "Trans-Tasman" identity between citizens of the latter being common.[221] New Zealand is a member of the Five Eyes intelligence sharing agreement, known formally as the UKUSA Agreement. The five members of this agreement compromise the core Anglosphere: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[222] Since 2012, New Zealand has had a partnership arrangement with NATO under the Partnership Interoperability Initiative.[223][224][225] According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, New Zealand is the 4th most peaceful country in the world.[226]

Military

[edit]

New Zealand's military services—the New Zealand Defence Force—comprise the Royal New Zealand Navy, the New Zealand Army and the Royal New Zealand Air Force.[227] New Zealand's national defence needs are modest since a direct attack is unlikely.[228] However, its military has had a global presence. The country fought in both world wars, with notable campaigns in Gallipoli, Crete,[229] El Alamein,[230] and Cassino.[231] The Gallipoli campaign played an important part in fostering New Zealand's national identity[232][233] and strengthened the ANZAC tradition it shares with Australia.[234]

In addition to Vietnam and the two world wars, New Zealand fought in the Second Boer War,[235] the Korean War,[236] the Malayan Emergency,[237] the Gulf War, and the Afghanistan War. It has contributed forces to several regional and global peacekeeping missions, such as those in Cyprus, Somalia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Sinai, Angola, Cambodia, the Iran–Iraq border, Bougainville, East Timor, and the Solomon Islands.[238]

Economy

[edit]

New Zealand has an advanced market economy,[239] with the country ranked 16th in the 2022[update] Human Development Index,[240] and fourth in the 2022[update] Index of Economic Freedom.[241] It is a high-income economy with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of United States dollar48,071 as of 2023.[242] The currency is the New Zealand dollar, informally known as the "Kiwi dollar"; it also circulates in the Cook Islands (see Cook Islands dollar), Niue, Tokelau, and the Pitcairn Islands.[243]

Historically, extractive industries have contributed strongly to New Zealand's economy, focusing at different times on sealing, whaling, flax, gold, kauri gum, and native timber.[244] The first shipment of refrigerated meat on the Dunedin in 1882 led to the establishment of meat and dairy exports to Britain, a trade which provided the basis for strong economic growth in New Zealand.[245] High demand for agricultural products from the United Kingdom and the United States helped New Zealanders achieve higher living standards than both Australia and Western Europe in the 1950s and 1960s.[246] In 1973, New Zealand's export market was reduced when the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community[247] and other compounding factors, such as the 1973 oil and 1979 energy crises, led to a severe economic depression.[248] Living standards in New Zealand fell behind those of Australia and Western Europe, and by 1982 New Zealand had the lowest per-capita income of all the developed nations surveyed by the World Bank.[249] In the mid-1980s New Zealand deregulated its agricultural sector by phasing out subsidies over a three-year period.[250][251] Since 1984, successive governments engaged in major macroeconomic restructuring (known first as Rogernomics and then Ruthanasia), rapidly transforming New Zealand from a protectionist and highly regulated economy to a liberalised free-trade economy.[252][253] New Zealand's gold production in 2015 was 12 tonnes.[254]

Unemployment peaked just above 10% in 1991 and 1992,[256] following the 1987 share market crash, but eventually fell to 3.7% in 2007 (ranking third from twenty-seven comparable OECD nations).[256] However, the 2008 financial crisis had a major effect on New Zealand, with the GDP shrinking for five consecutive quarters, the longest recession in over thirty years,[257][258] and unemployment rising back to 7% in late 2009.[259] The lowest unemployment rate recorded using the current methodology was in December 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, at 3.2%.[260] Unemployment rates for different age groups follow similar trends but are consistently higher among youth. During the September 2021 quarter, the general unemployment rate was around 3.2%, while the unemployment rate for youth aged 15 to 24 was 9.2%.[256][261] New Zealand has experienced a series of "brain drains" since the 1970s[262] that still continue today.[263] Nearly one-quarter of highly skilled workers live overseas, mostly in Australia and Britain, which is the largest proportion from any developed nation.[264] In recent decades, however, a "brain gain" has brought in educated professionals from Europe and less developed countries.[265][266] Today New Zealand's economy benefits from a high level of innovation.[267]

Poverty in New Zealand is characterised by growing income inequality; wealth in New Zealand is highly concentrated,[268] with the top 1% of the population owning 16% of the country's wealth, and the richest 5% owning 38%, leaving a stark contrast where half the population, including state beneficiaries and pensioners, receive less than $24,000.[269] Moreover, child poverty in New Zealand has been identified by the Government as a major societal issue;[270][271] the country has 12.0% of children living in low-income households that have less than 50% of the median equivalised disposable household income as of June 2022[update].[272] Poverty has a disproportionately high effect in ethnic-minority households, with a quarter (23.3%) of Māori children and almost a third (28.6%) of Pacific Islander children living in poverty as of 2020[update].[270]

Trade

[edit]New Zealand is heavily dependent on international trade,[273] particularly in agricultural products.[274] Exports account for 24% of its output,[97] making New Zealand vulnerable to international commodity prices and global economic slowdowns. Food products made up 55% of the value of all the country's exports in 2014; wood was the second largest earner (7%).[275] New Zealand's main trading partners, as at June 2018[update], are China (NZ$27.8b), Australia ($26.2b), the European Union ($22.9b), the United States ($17.6b), and Japan ($8.4b).[276] On 7 April 2008, New Zealand and China signed the New Zealand–China Free Trade Agreement, the first such agreement China has signed with a developed country.[277] In July 2023, New Zealand and the European Union entered into the EU–New Zealand Free Trade Agreement, which eliminated tariffs on several goods traded between the two regions.[278] This free trade agreement expanded on the pre-existing free trade agreement[279] and saw a reduction in tariffs on meat and dairy[280] in response to feedback from the affected industries.[281]

The service sector is the largest sector in the economy, followed by manufacturing and construction and then farming and raw material extraction.[97] Tourism plays a significant role in the economy, contributing $12.9 billion (or 5.6%) to New Zealand's total GDP and supporting 7.5% of the total workforce in 2016.[282] In 2017, international visitor arrivals were expected to increase at a rate of 5.4% annually up to 2022.[282]

Wool was New Zealand's major agricultural export during the late 19th century.[244] Even as late as the 1960s it made up over a third of all export revenues,[244] but since then its price has steadily dropped relative to other commodities,[283] and wool is no longer profitable for many farmers.[284] In contrast, dairy farming increased, with the number of dairy cows doubling between 1990 and 2007,[285] to become New Zealand's largest export earner.[286] In the year to June 2018, dairy products accounted for 17.7% ($14.1 billion) of total exports,[276] and the country's largest company, Fonterra, controls almost one-third of the international dairy trade.[287] Other exports in 2017–18 were meat (8.8%), wood and wood products (6.2%), fruit (3.6%), machinery (2.2%) and wine (2.1%).[276] New Zealand's wine industry has followed a similar trend to dairy, the number of vineyards doubling over the same period,[288] overtaking wool exports for the first time in 2007.[289][290]

Infrastructure

[edit]In 2015, renewable energy generated 40.1% of New Zealand's gross energy supply.[291] The majority of the country's electricity supply is generated from hydroelectric power, with major schemes on the Waikato, Waitaki and Clutha / Mata-Au rivers, as well as at Manapouri. Geothermal power is also a significant generator of electricity, with several large stations located across the Taupō Volcanic Zone in the North Island. The four main companies in the generation and retail market are Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Mercury Energy and Meridian Energy. State-owned Transpower operates the high-voltage transmission grids in the North and South Islands, as well as the Inter-Island HVDC link connecting the two together.[291]

The provision of water supply and sanitation is generally of good quality. Regional authorities provide water abstraction, treatment and distribution infrastructure to most developed areas.[292][293]

New Zealand's transport network comprises 94,000 kilometres (58,410 mi) of roads, including 199 kilometres (124 mi) of motorways,[294] and 4,128 kilometres (2,565 mi) of railway lines.[97] Most major cities and towns are linked by bus services, although the private car is the predominant mode of transport.[295] The country's railways were privatised in 1993 but were re-nationalised by the government in stages between 2004 and 2008. The state-owned enterprise KiwiRail now operates the railways, with the exception of commuter services in Auckland and Wellington, which are operated by Auckland One Rail and Transdev Wellington respectively.[296] Railways run the length of the country, although most lines now carry freight rather than passengers.[297] The road and rail networks in the two main islands are linked by roll-on/roll-off ferries between Wellington and Picton, operated by Interislander (part of KiwiRail) and Bluebridge. Most international visitors arrive via air.[298] New Zealand has four international airports: Auckland, Christchurch, Queenstown and Wellington; however, only Auckland and Christchurch offer non-stop flights to countries other than Australia or Fiji.[299]

The New Zealand Post Office had a monopoly over telecommunications in New Zealand until 1987 when Telecom New Zealand was formed, initially as a state-owned enterprise and then privatised in 1990.[300] Chorus, which was split from Telecom (now Spark) in 2011,[301] still owns the majority of the telecommunications infrastructure, but competition from other providers has increased.[300] A large-scale rollout of gigabit-capable fibre to the premises, branded as Ultra-Fast Broadband, began in 2009 with a target of being available to 87% of the population by 2022.[302] As of 2017[update], the United Nations International Telecommunication Union ranks New Zealand 13th in the development of information and communications infrastructure.[303]

Science and technology

[edit]Early indigenous contribution to science in New Zealand was by Māori tohunga accumulating knowledge of agricultural practice and the effects of herbal remedies in the treatment of illness and disease.[304] Cook's voyages in the 1700s and Darwin's in 1835 had important scientific botanical and zoological objectives.[305] The establishment of universities in the 19th century fostered scientific discoveries by notable New Zealanders including Ernest Rutherford for splitting the atom, William Pickering for rocket science, Maurice Wilkins for helping discover DNA, Beatrice Tinsley for galaxy formation, Archibald McIndoe for plastic surgery, and Alan MacDiarmid for conducting polymers.[306]

Crown Research Institutes (CRIs) were formed in 1992 from existing government-owned research organisations. Their role is to research and develop new science, knowledge, products and services across the economic, environmental, social and cultural spectrum for the benefit of New Zealand.[307] The total gross expenditure on research and development (R&D) as a proportion of GDP rose to 1.37% in 2018, up from 1.23% in 2015. New Zealand ranks 21st in the OECD for its gross R&D spending as a percentage of GDP.[308] New Zealand was ranked 25th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[309]

The New Zealand Space Agency was created by the government in 2016 for space policy, regulation and sector development. Rocket Lab was the first commercial rocket launcher in the country.[310]

The majority of private and commercial research organisations in New Zealand are focused on the agricultural and fisheries sectors. Examples include the Cawthron Institute, the Livestock Improvement Corporation, the Fonterra Research and Development Centre, the Bragato Research Institute, the Kiwifruit Breeding Centre, and B+LNZ Genetics.

Demographics

[edit]

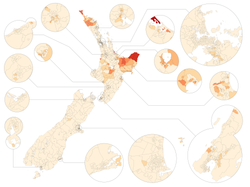

The 2023 New Zealand census enumerated a resident population of 4,993,923, an increase of 6.3% over the 2018 census figure.[4] As of August 2025, the total population has risen to an estimated 5,231,143.[311] New Zealand's population increased at a rate of 1.9% per year in the seven years ended June 2020. In September 2020 Statistics New Zealand reported that the population had climbed above 5 million people in September 2019, according to population estimates based on the 2018 census.[312][n 9]

New Zealand's population today is concentrated to the north of the country, with around 76.5% of the population living in the North Island and 23.5% in the South Island as of June 2024.[314] During the 20th century, New Zealand's population drifted north. In 1921, the country's median centre of population was located in the Tasman Sea west of Levin in Manawatū-Whanganui; by 2017, it had moved 280 km (170 mi) north to near Kawhia in Waikato.[315]

New Zealand is a predominantly urban country, with 84.7% of the population living in urban areas, and 51.2% of the population living in the seven cities with populations exceeding 100,000.[314] Auckland, with over 1.4 million residents, is by far the largest city.[314] New Zealand cities generally rank highly on international livability measures. For instance, in 2016, Auckland was ranked the world's third most liveable city and Wellington the twelfth by the Mercer Quality of Living Survey.[316]

The median age of the New Zealand population at the 2018 census was 37.4 years,[317] with life expectancy in 2017–2019 being 80.0 years for males and 83.5 years for females.[318] While New Zealand is experiencing sub-replacement fertility, with a total fertility rate of 1.6 in 2020, the fertility rate is above the OECD average.[319][320] By 2050, the median age is projected to rise to 43 years and the percentage of people 60 years of age and older to rise from 18% to 29%.[321] In 2016 the leading cause of death was cancer at 30.3%, followed by ischaemic heart disease (14.9%) and cerebrovascular disease (7.4%).[322] As of 2016[update], total expenditure on health care (including private sector spending) is 9.2% of GDP.[323]

Largest cities or towns in New Zealand

Statistics New Zealand June 2024 estimate (SSGA18 boundaries)[314] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

| 1 | Auckland | Auckland | 1,530,500 | 11 | Porirua | Wellington | 60,400 | ||

| 2 | Christchurch | Canterbury | 400,600 | 12 | New Plymouth | Taranaki | 60,400 | ||

| 3 | Wellington | Wellington | 208,800 | 13 | Rotorua | Bay of Plenty | 57,900 | ||

| 4 | Hamilton | Waikato | 189,700 | 14 | Whangārei | Northland | 56,100 | ||

| 5 | Tauranga | Bay of Plenty | 161,300 | 15 | Nelson | Nelson | 50,800 | ||

| 6 | Lower Hutt | Wellington | 112,300 | 16 | Hastings | Hawke's Bay | 50,200 | ||

| 7 | Dunedin | Otago | 103,200 | 17 | Invercargill | Southland | 50,800 | ||

| 8 | Palmerston North | Manawatū-Whanganui | 81,800 | 18 | Upper Hutt | Wellington | 44,500 | ||

| 9 | Napier | Hawke's Bay | 66,800 | 19 | Whanganui | Manawatū-Whanganui | 42,600 | ||

| 10 | Hibiscus Coast | Auckland | 66,800 | 20 | Gisborne | Gisborne | 38,300 | ||

Ethnicity and immigration

[edit]

In the 2023 census, a total of 67.8% of New Zealand residents identified ethnically as European, with 54.1% identifying as European alone,[324] and 19.6% as Māori, with 7.3% identifying as Māori alone. Other major ethnic groups include Asian (17.3% total, 15.7% alone) and Pacific peoples (8.9%, 5.5% alone).[n 3][4] New Zealand has a large multiethnic population, with the largest mixed groups being European and Māori (8.2%), Māori and Pacific peoples (0.9%), and European and Asian (0.9%).[325] The population has become more multicultural and diverse in recent decades: in 1961, the census reported that the population of New Zealand was 92% European and 7% Māori, with Asian and Pacific minorities sharing the remaining 1%.[326] However, New Zealand's non-European population is disproportionately concentrated in the North Island and especially in the Auckland Region: while Auckland is home to 33% of New Zealand's population, it is home to 62% of the country's Pasifika population and 60% of its Asian population.[4]

While the demonym for a New Zealand citizen is New Zealander, the informal "Kiwi" is commonly used both internationally[327] and by locals.[328] The Māori loanword Pākehā has been used to refer to New Zealanders of European descent, although some reject this name. The word today is increasingly used to refer to all non-Polynesian New Zealanders.[329]

The Māori were the first people to reach New Zealand, followed by the early European settlers. Following colonisation, immigrants were predominantly from Britain, Ireland and Australia because of restrictive policies similar to the White Australia policy.[330] There was also significant Dutch, Dalmatian,[331] German, and Italian immigration, together with indirect European immigration through Australia, North America, South America and South Africa.[332][333] Net migration increased after the Second World War; in the 1970s and 1980s policies on immigration were relaxed, and immigration from Asia was promoted.[333][334] In 2009–10, an annual target of 45,000–50,000 permanent residence approvals was set by the New Zealand Immigration Service—more than one new migrant for every 100 New Zealand residents.[335] In the 2018 census, 27.4% of people counted were not born in New Zealand, up from 25.2% in the 2013 census. Over half (52.4%) of New Zealand's overseas-born population lives in the Auckland Region.[336] The United Kingdom remains the largest source of New Zealand's immigrant population, with around a quarter of all overseas-born New Zealanders born there; other major sources of New Zealand's overseas-born population are China, India, Australia, South Africa, Fiji and Samoa.[337] The number of fee-paying international students and international exchange students increased sharply in the late 1990s, with more than 20,000 studying in public tertiary institutions in 2002.[338]

Language

[edit]

English is the predominant language in New Zealand, spoken by 95.4% of the population.[340] New Zealand English is a variety of the language with a distinctive accent and lexicon.[341] It is similar to Australian English, and many speakers from the Northern Hemisphere are unable to tell the accents apart.[342] The most prominent differences between the New Zealand English dialect and other English dialects are the shifts in the short front vowels: the short-i sound (as in kit) has centralised towards the schwa sound (the a in comma and about); the short-e sound (as in dress) has moved towards the short-i sound; and the short-a sound (as in trap) has moved to the short-e sound.[343]

After the Second World War, Māori were discouraged or forced from speaking their own language (te reo Māori) in schools and workplaces, and it existed as a community language only in a few remote areas.[344] The Native Schools Act 1867 required instruction in English in all schools, and while there was no official policy banning children from speaking Māori, many suffered from physical abuse if they did so.[345][346][347] The Māori language has recently undergone a process of revitalisation,[348] being declared one of New Zealand's official languages in 1987,[349] and is spoken by 4.0% of the population.[340][n 10] There are now Māori language-immersion schools and two television channels that broadcast predominantly in Māori.[351] Many places have both their Māori and English names officially recognised.[352]

As recorded in the 2018 census,[340] Samoan is the most widely spoken non-official language (2.2%), followed by "Northern Chinese" (including Mandarin, 2.0%), Hindi (1.5%), and French (1.2%). New Zealand Sign Language was reported to be understood by 22,986 people (0.5%); it became one of New Zealand's official languages in 2006.[353]

Religion

[edit]

At the 2023 census, 51.6% of population stated they had no religion,[355] up from 48.2% in 2018 census.[340] Christians are the single largest religious group, forming 32.3% of the population,[355] compared to 36.5% in 2018.[340] Hindus are the second largest religious minority, forming the 2.9% of population, followed by Muslims on 1.5%.[355] The Auckland Region exhibited the greatest religious diversity.[356]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary schooling is compulsory for children aged 6 to 16, with the majority of children attending from the age of 5.[357] There are 13 school years and attending state (public) schools is free to New Zealand citizens and permanent residents from a person's 5th birthday to the end of the calendar year following their 19th birthday.[358] New Zealand has an adult literacy rate of 99%,[97] and over half of the population aged 15 to 29 hold a tertiary qualification.[357]

There are five types of government-owned tertiary institutions: universities, colleges of education, polytechnics, specialist colleges, and wānanga,[359] in addition to private training establishments.[360] In 2021, in the population aged 25–64; 13% had no formal qualification, 21% had a school qualification, 28% had a tertiary certificate or diploma, and 35% have a bachelor's degree or higher.[361] The OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment ranks New Zealand as the 28th best in the OECD for maths, 13th best for science, and 11th best for reading.[362]

Culture

[edit]Early Māori adapted the tropically based east Polynesian culture in line with the challenges associated with a larger and more diverse environment, eventually developing their own distinctive culture. Social organisation was largely communal with families (whānau), subtribes (hapū) and tribes (iwi) ruled by a chief (rangatira), whose position was subject to the community's approval.[363] The British and Irish immigrants brought aspects of their own culture to New Zealand and also influenced Māori culture,[364][365] particularly with the introduction of Christianity.[366] However, Māori still regard their allegiance to tribal groups as a vital part of their identity, and Māori kinship roles resemble those of other Polynesian peoples.[367] More recently, American, Australian, Asian and other European cultures have exerted influence on New Zealand. Non-Māori Polynesian cultures are also apparent, with Pasifika, the world's largest Polynesian festival, now an annual event in Auckland.[368]

The largely rural life in early New Zealand led to the image of New Zealanders being rugged, industrious problem solvers.[369] Modesty was expected and enforced through the "tall poppy syndrome", where high achievers received harsh criticism.[370] At the time, New Zealand was not known as an intellectual country.[371] From the early 20th century until the late 1960s, Māori culture was suppressed by the attempted assimilation of Māori into British New Zealanders.[344] In the 1960s, as tertiary education became more available, and cities expanded[372] urban culture began to dominate.[373] However, rural imagery and themes are common in New Zealand's art, literature and media.[374]

New Zealand's national symbols are influenced by natural, historical, and Māori sources. The silver fern is an emblem appearing on army insignia and sporting team uniforms.[375] Certain items of popular culture thought to be unique to New Zealand are called "Kiwiana".[375]

Art

[edit]

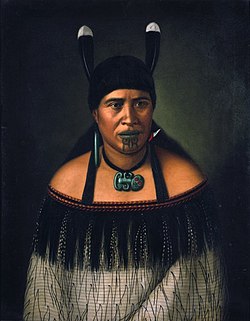

As part of the resurgence of Māori culture, the traditional crafts of carving and weaving are now more widely practised, and Māori artists are increasing in number and influence.[376] Most Māori carvings feature human figures, generally with three fingers and either a natural-looking, detailed head or a stylised version.[377] Surface patterns consisting of spirals, ridges, notches and fish scales decorate most carvings.[378] The pre-eminent Māori architecture consisted of carved meeting houses (wharenui) decorated with symbolic carvings and illustrations. These buildings were originally designed to be constantly rebuilt, changing and adapting to different whims or needs.[379]

Māori decorated the white wood of buildings, canoes and cenotaphs using red (a mixture of red ochre and shark fat) and black (made from soot) paint and painted pictures of birds, reptiles and other designs on cave walls.[380] Māori tattoos (moko) consisting of coloured soot mixed with gum were cut into the flesh with a bone chisel.[381] Since European arrival paintings and photographs have been dominated by landscapes, originally not as works of art but as factual portrayals of New Zealand.[382] Portraits of Māori were also common, with early painters often portraying them as an ideal race untainted by civilisation.[382] The country's isolation delayed the influence of European artistic trends allowing local artists to develop their own distinctive style of regionalism.[383] During the 1960s and 1970s, many artists combined traditional Māori and Western techniques, creating unique art forms.[384] New Zealand art and craft has gradually achieved an international audience, with exhibitions in the Venice Biennale in 2001 and the "Paradise Now" exhibition in New York in 2004.[376][385]

Māori cloaks are made of fine flax fibre and patterned with black, red and white triangles, diamonds and other geometric shapes.[386] Greenstone was fashioned into earrings and necklaces, with the most well-known design being the hei-tiki, a distorted human figure sitting cross-legged with its head tilted to the side.[387] Europeans brought English fashion etiquette to New Zealand, and until the 1950s most people dressed up for social occasions.[388] Standards have since relaxed and New Zealand fashion has received a reputation for being casual, practical and lacklustre.[389][390] However, the local fashion industry has grown significantly since 2000, doubling exports and increasing from a handful to about 50 established labels, with some labels gaining international recognition.[390]

Literature

[edit]Māori quickly adopted writing as a means of sharing ideas, and many of their oral stories and poems were converted to the written form.[391] Most early English literature was obtained from Britain, and it was not until the 1950s when local publishing outlets increased that New Zealand literature started to become widely known.[392] Although still largely influenced by global trends (modernism) and events (the Great Depression), writers in the 1930s began to develop stories increasingly focused on their experiences in New Zealand. During this period, literature changed from a journalistic activity to a more academic pursuit.[393] Participation in the world wars gave some New Zealand writers a new perspective on New Zealand culture and with the post-war expansion of universities local literature flourished.[394] Dunedin is a UNESCO City of Literature.[395]

Media and entertainment

[edit]

New Zealand music has been influenced by blues, jazz, country, rock and roll and hip hop, with many of these genres given a unique New Zealand interpretation.[396] Māori developed a varied musical tradition around songs and chants, including ceremonial performances, laments, and love songs.[397] Instruments (taonga pūoro), such as flutes and percussion, began being used as spiritual tools, entertainment, and signalling devices.[398][399] Early settlers brought over their ethnic music, with brass bands and choral music being popular, and musicians began touring New Zealand in the 1860s.[400][401] Pipe bands became widespread during the early 20th century.[402] The New Zealand recording industry began to develop from 1940 onwards, and many New Zealand musicians have obtained success in Britain and the United States.[396] Some artists release Māori language songs, and the Māori tradition-based art of kapa haka (song and dance) has made a resurgence.[403] The New Zealand Music Awards are held annually by Recorded Music NZ; the awards were first held in 1965 by Reckitt & Colman as the Loxene Golden Disc awards.[404] Recorded Music NZ also publishes the country's official weekly record charts.[405]

Public radio was introduced in New Zealand in 1922.[407] A state-owned television service began in 1960.[408] Deregulation in the 1980s saw a sudden increase in the numbers of radio and television stations.[409] New Zealand television primarily broadcasts American and British programming, along with many Australian and local shows.[410] The number of New Zealand films significantly increased during the 1970s. In 1978 the New Zealand Film Commission started assisting local film-makers, and many films attained a world audience, some receiving international acknowledgement.[409] The highest-grossing New Zealand films are Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Boy, The World's Fastest Indian, Whale Rider, Once Were Warriors, Heavenly Creatures, What We Do in the Shadows and The Piano.[411][412] The country's diverse scenery and compact size, plus government incentives,[413] have encouraged some producers to shoot very big-budget and well known productions in New Zealand, including The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit film trilogies, Avatar, The Chronicles of Narnia, King Kong, Wolverine, The Last Samurai, The Power of the Dog, Alien Covenant, Mulan, and A Minecraft Movie.[414][415][416] The New Zealand media industry is dominated by a small number of companies, most of which are foreign-owned, although the state retains ownership of some television and radio stations.[417] Since 1994, Freedom House has consistently ranked New Zealand's press freedom in the top twenty, with the 19th freest media as of 2015.[update][418]

Cuisine

[edit]

The national cuisine has been described as Pacific Rim, incorporating the native Māori cuisine and diverse culinary traditions introduced by settlers and immigrants from Europe, Polynesia, and Asia.[419] New Zealand yields produce from land and sea—most crops and livestock, such as maize, potatoes and pigs, were gradually introduced by the early European settlers.[420] Distinctive ingredients or dishes include lamb, salmon, kōura (crayfish),[421] Bluff oysters, whitebait, pāua (abalone), mussels, scallops, pipi and tuatua (types of New Zealand shellfish),[422] kūmara (sweet potato), kiwifruit, tamarillo, and pavlova (considered a national dessert).[423][419] A hāngī is a traditional Māori method of cooking food using heated rocks buried in a pit oven; still used for large groups on special occasions,[424] such as tangihanga.[425]

Sport

[edit]

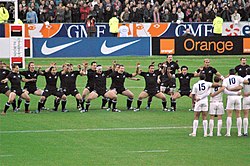

Most of the major sporting codes played in New Zealand have British origins.[426] Rugby union is considered the national sport[427] and attracts the most spectators.[428] Golf, netball, tennis and cricket have the highest rates of adult participation, while netball, rugby union and football (soccer) are particularly popular among young people.[428][429] Horse racing is one of the most popular spectator sports in New Zealand and was part of the "rugby, racing, and beer" subculture during the 1960s.[430] Around 54% of New Zealand adolescents participate in sports for their school.[429] Victorious rugby tours to Australia and the United Kingdom in the late 1880s and the early 1900s played an early role in instilling a national identity.[431] Māori participation in European sports was particularly evident in rugby, and the country's team performs a haka, a traditional Māori challenge, before international matches.[432] New Zealand is known for its extreme sports, adventure tourism[433] and strong mountaineering tradition, as seen in the success of notable New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary.[434][435] Other outdoor pursuits such as cycling, fishing, swimming, running, tramping, canoeing, hunting, snowsports, surfing and sailing are also popular.[436] New Zealand has seen regular sailing success in the America's Cup regatta since 1995.[437] The Polynesian sport of waka ama racing has experienced a resurgence of interest in New Zealand since the 1980s.[438]

New Zealand has competitive international teams in rugby union, rugby league, netball, cricket, softball, and sailing. New Zealand participated at the Summer Olympics in 1908 and 1912 as a joint team with Australia, before first participating on its own in 1920.[439] The country has ranked highly on a medals-to-population ratio at recent Games.[440][441][442] The All Blacks, the national rugby union team, are the most successful in the history of international rugby.[443] They have won the Rugby World Cup three times.[444]

New Zealand is ranked 5th in the ICC Men's Test Team Rankings 2025 with a rating of 100.[445]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "God Save the King" is officially one of New Zealand's two national anthems, but is usually reserved for situations relevant to the monarchy.[1][2]

- ^ English is a de facto official language due to its widespread use.[3]

- ^ a b Ethnicity figures add to more than 100% as people could choose more than one ethnic group in the census.

- ^ Excluding the Māori-based churches of Rātana and Ringatū

- ^ The proportion of New Zealand's area (excluding estuaries) covered by rivers, lakes and ponds, based on figures from the New Zealand Land Cover Database,[8] is (357526 + 81936) / (26821559 – 92499–26033 – 19216)=1.6%. If estuarine open water, mangroves, and herbaceous saline vegetation are included, the figure is 2.2%.

- ^ The Chatham Islands have a separate time zone, 45 minutes ahead of the rest of New Zealand.

- ^ Clocks are advanced by an hour from the last Sunday in September until the first Sunday in April.[16] Daylight saving time is also observed in the Chatham Islands, 45 minutes ahead of NZDT.

- ^ A person born on or after 1 January 2006 acquires New Zealand citizenship at birth only if at least one parent is a New Zealand citizen or permanent resident. All persons born on or before 31 December 2005 acquired citizenship at birth (jus soli).[197]

- ^ A provisional estimate initially indicated the milestone was reached six months later in March 2020, before population estimates were rebased from the 2013 census to the 2018 census.[313]

- ^ In 2015, 55% of Māori adults (aged 15 years and over) reported knowledge of te reo Māori. Of these speakers, 64% use Māori at home and 50,000 can speak the language "very well" or "well".[350]

References

[edit]- ^ "Protocol for using New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "New Zealand's national anthems". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Fifth Periodic Report of the Government of New Zealand (PDF) (Report). New Zealand Government. 21 December 2007. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

In addition to the Māori language, New Zealand Sign Language is also an official language of New Zealand. The New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006 permits the use of NZSL in legal proceedings, facilitates competency standards for its interpretation and guides government departments in its promotion and use. English, the medium for teaching and learning in most schools, is a de facto official language by virtue of its widespread use. For these reasons, these three languages have special mention in the New Zealand Curriculum.

- ^ a b c d e "2023 Census population counts (by ethnic group, age, and Māori descent) and dwelling counts". Statistics New Zealand. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Comparison of 2013, 2018, and 2023 censuses by religious affiliation". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi". mch.govt.nz. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand Population". Worldometers. 14 December 2024. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ "The New Zealand Land Cover Database". New Zealand Land Cover Database 2. Ministry for the Environment. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Population clock". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2021. The population estimate shown is automatically calculated daily at 00:00 UTC and is based on data obtained from the population clock on the date shown in the citation.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025".

- ^ Household income and housing-cost statistics: Year ended June 2022. Statistics New Zealand. 23 March 2023. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2025" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "New Zealand Daylight Time Order 2007 (SR 2007/185)". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. 6 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ There is no official all-numeric date format for New Zealand, but government recommendations generally follow Australian date and time notation. See The Govt.nz style guide, New Zealand Government, 22 July 2020, archived from the original on 25 July 2021, retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b Wilson, John (March 2009). "European discovery of New Zealand – Tasman's achievement". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Bathgate, John. "The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout: Volume 44. Chapter 1, Discovery and Settlement". NZETC. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

He named the country Staaten Land, in honour of the States-General of Holland, in the belief that it was part of the great southern continent.

- ^ Mackay, Duncan (1986). "The Search for the Southern Land". In Fraser, B. (ed.). The New Zealand Book of Events. Auckland: Reed Methuen. pp. 52–54.

- ^ Wood, James (1900). The Nuttall Encyclopaedia: Being a Concise and Comprehensive Dictionary of General Knowledge. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co. p. iii. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b McKinnon, Malcolm (November 2009). "Place names – Naming the country and the main islands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Grant (Lord Glenelg), Charles (1836). "Extract of a Despatch from Lord Glenelg to Major-General Sir Richard Bourke, New South Wales". Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021 – via Waitangi Associates.

- ^ Palmer 2008, p. 41.

- ^ King 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Hay, Maclagan & Gordon 2008, p. 72.

- ^ a b Mein Smith 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Brunner, Thomas (1851). The Great Journey: An expedition to explore the interior of the Middle Island, New Zealand, 1846-8. Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b Williamson, Maurice (10 October 2013). "Names of NZ's two main islands formalised" (Press release). New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Ministry of Health (24 June 2021). "COVID-19: Elimination strategy for Aotearoa New Zealand". Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Larner, Wendy (31 May 2021). "COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 51 (sup1): S1 – S3. Bibcode:2021JRSNZ..51S...1L. doi:10.1080/03036758.2021.1908208. ISSN 0303-6758.

- ^ "Using 'Aotearoa' and 'New Zealand' together 'as it should be' - Jacinda Ardern". Newshub. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl; Spriggs, Matthew (1993). "Late colonization of East Polynesia". Antiquity. 67 (255): 200–217. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00045324. ISSN 1745-1744. S2CID 162638670.

- ^ Jacomb, Chris; Anderson, Atholl; Higham, Thomas (1999). "Dating the first New Zealanders: The chronology of Wairau Bar". Antiquity. 73 (280): 420–427. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00088360. ISSN 1745-1744. S2CID 161058755.

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (5): 1815–20. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1815W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. PMC 3033267. PMID 21187404.

- ^ "Kupe". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Te Papa Tongarewa. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ Howe, K.R. (2005). "'Ideas about Māori origins – 1840s–early 20th century: Māori tradition and the Great Fleet'". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Walters, Richard; Buckley, Hallie; Jacomb, Chris; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (7 October 2017). "Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (4): 351–376. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y.

- ^ Jacomb, Chris; Holdaway, Richard N.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Bunce, Michael; Oskam, Charlotte L.; Walter, Richard; Brooks, Emma (2014). "High-precision dating and ancient DNA profiling of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) eggshell documents a complex feature at Wairau Bar and refines the chronology of New Zealand settlement by Polynesians". Journal of Archaeological Science. 50: 24–30. Bibcode:2014JArSc..50...24J. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.023. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Walters, Richard; Buckley, Hallie; Jacomb, Chris; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (7 October 2017). "Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand". Journal of World Prehistory. 30 (4): 351–376. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y.

- ^ Roberton, J. B. W. (1956). "Genealogies as a basis for Maori chronology". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 65 (1): 45–54. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Moodley, Y.; Linz, B.; Yamaoka, Y.; et al. (2009). "The Peopling of the Pacific from a Bacterial Perspective". Science. 323 (5913): 527–530. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..527M. doi:10.1126/science.1166083. PMC 2827536. PMID 19164753.

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Anderson, A. J.; Higham, T. F. G.; Worthy, T. H. (2008). "Dating the late prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal Pacific rat". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (22): 7676–80. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.7676W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801507105. PMC 2409139. PMID 18523023.