Panchayati Revolution

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 26 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 26 min

| Panchayati Revolution | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chir Singh (Sher Singh), Maharajah of the Sikhs and King of the Punjab with his retinue hunting near Lahore, from 'Voyages in India', 1859 (litho). Voyages dans l'Inde' by Alexis Soltykoff. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

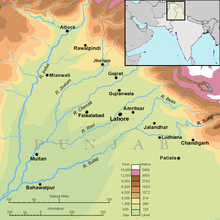

The Panchayati Revolution was fought between the Lahore Durbar and the Khalsa Panchayat between 1841 and 1844 in a wide variety of areas.[1] It resulted in the First Anglo-Sikh War to start and the end to Sikh dominance in the Lahore Durbar.[2]

Background[edit]

After the demise of Maharaja Ranjit Singh the Lahore Durbar entered an era of complete disarray- with influential families and his descendants tussling for more power.[3] The Khalsa Panchayat was very patient with the next three rulers as they were either able administrators or they were not able to hold a firm grip on the political situation of the Punjab.[4] The Sikh jaghirdars who held vast swathes of land in West Punjab all assisted the formation of the Khalsa Panchayat who embarked on a resurgence of Sikh principles in the Lahore Durbar and a collective fight against the Dogras, British and Europeans who threatened their sovereignty.[4] They highly respected Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Jarnail Hari Singh Nalwa for their devotion to the Khalsa Panth and following the Khalsas' demands.[5] They believed that the new rulers of the Punjab were weak hearted and could not contain the Khalsas' rampant bloodlust that was accumulating as the days went by.[6]

Events in Punjab[edit]

After the transfer of the beloved Maharaja Sher Singh to the throne and the death of Malika Muqaddasa Chand Kaur- the Sikh Khalsa Army agreed to many of his terms and allowed for some level of consensus.[7] In the first six months of his rule he parted with nearly 9,500,000 rupees to the Khalsa soldiers for their wages although even this did not appease the men, who threatened to depose him.[7] Although they grew used to him- the wars in Ladakh and Afghanistan fought by, mostly, Dogras and Punjabi Muslims were clear signs that the Lahore Durbar did not trust Sikhs anymore.[7] The Panchayat was a council of elders which regulated the affairs of the villages from which they came.[7] This institution had been introduced in the army, and each regiment had begun to elect its own Panches, whose duty was to deliberate on the orders of the commanding officer and then to make their recommendations to the men.[8] In the army, the Panchayats did not develop into a proper administrative system, and much depended on the ability of the elected men.[8] In order to maintain their influence the Panches often pressed for concessions and increases in wages which were unreasonable.[8] Some senior Panches became powerful enough to be able to auction posts of officers; they appointed deputies (Karpanches) to convey their decisions to the troops and ensure their acceptance.[9]

The largest Khalsa Panchayats were that of the Sandhawalias, Majithias, Attariwalas, Mannawalas, Nalwas and Waraichs.[10] These were either faithful to the Lahore Durbar, faithful toward the order of Guru Gobind Singh or were not involved in either side.[11] British observers decried it as a "dangerous military democracy" and British representatives and visitors in the Punjab described the regiments as preserving "puritanical" order internally, but also as being in a perpetual state of mutiny or rebellion against the central Durbar.[12] They thrived on the concept of individual sovereignty and used the weak Maharaja Sher Singh to extract money and land out of- although during his time the Dogra influence grew much further including the plans of Raja Dhian Singh Dogra, Raja Hira Singh Dogra and Pandit Jalla.[12] The attitude of the British Government towards Maharaja Sher Singh's succession was somewhat ambivalent.[12] The Governor General recognized him as ruler of the Punjab but at the same time gave asylum to Raja Attar Singh Sandhawalia and did nothing to prevent him from raising troops to invade the Punjab including Akalgarh and Kot Kapura across the Sutlej.[12]

"What the Punjab had prayed for was a dictator. What it got was a handsome and well-meaning dandy who knew more about French wines and perfumes than he did about statecraft."

— Khushwant Singh, History of the Sikhs Volume II

Outbreak and Course of the War[edit]

Sandhawalia Revolt[edit]

The Sandhawalias sent invitations to the Dogras — Dhian Singh, Hira Singh, and Suchet Singh — to join them. Dhian Singh fell into the trap and came to the fort with a very small escort.[13] He was killed and his bodyguard of 25 was hacked to pieces on 15 September 1843.[14] When Suchet Singh and Hira Singh, who were encamped a couple of miles outside the city, received news of Dhian Singh's murder, they immediately sought refuge in the cantonment and appealed to the Khalsa Panchayat, which at that time was unorganized, to avenge the murders.[15]

The Sandhawalias occupied the fort and the palace in the belief that they would now rule the Punjab.[16] They had reckoned without the people.[16] Next morning Nihangs stormed in through the breaches and captured the citadel.[16] The assassins and 600 of their troops were put to the sword of Jathedar Akali Baba Hanuman Singh Nihang.[16] But Attar Singh Sandhawalia remained.[16] He received the news of the capture of Lahore by the army and fled across the Sutlej, where he was given asylum by the British and raised an army to capture the Cis-Sutlej territories of the Sikhs although Maharaja Sher Singh dared the British saying that he would, "rip open their bellies."[7]

Pathan Revolt[edit]

When coming back from the Afghanistan campaign Major Broadfoot's aggressive attitude towards the Durbar made the Punjabis feel exploited.[16] He often made his party fire on the Punjabi Muslims who were part of the Sikh Khalsa Army and helping the British.[17] When Broadfoot had crossed the Indus, he called on the Pathan tribesmen to revolt against the Durbar- and some of them did manage to escape and start a revolt which was immediately crushed.[18] The whole proceeding merely served to irritate and excite the distrust of the Sikhs generally, and to give Sher Singh an opportunity of pointing out to his mutineer soldiers that the Punjab was surrounded by English armies both ready and willing to make war upon them.[19][20] Malik Fateh Khan Tiwana rebelled in the south, close to what was Bahawalpur except on the other side of the Sutlej and in the same week Raja Gulab Singh Dogra incited the frontier tribesmen to plunder Peshawar.[21]

Maharaja Bir Singh Naurangabad took it upon himself to cure the state of the Lahore Durbar internally and hence started calling in the Panchayats.[22] He was declared as the Maharaja of the Khalsa Panchayat and Maharaja Duleep Singh was of the Lahore Durbar.[22] Maharaja Bir Singh Naurangabad advised the Attariwalas to gather their armies at Attock to invade Peshawar although they did not pay any heed as they served Maharaja Duleep Singh.[23] Diwan Mulraj Chopra was sent against Fateh Khan and in an action fought at Mitha Tiwana, about 900 men were killed on both sides, Fateh Khan lost his son and was compelled to submit to the Khalsa.[16][24] Maharaja Duleep Singh, being a child, was a puppet of his vehemently Anti-Sikh mother Rani Jindan, and the Dogras hence he never acted against the Pathan tribesmen or the Europeans who started to communicate with the British for the takeover of the Punjab.[25]

Anti-European Sentiment[edit]

Sacking of Porothar[edit]

Maharaja Bir Singh Naurangabad's first target was Major Ford who was planning the First Anglo-Sikh War on British terms along with Major Broadfoot.[26] Maharaja Bir Singh sent 300 Sikhs under Diwan Baisakha Singh to kill Major Ford.[26] Major Ford was beaten up and imprisoned by Maharaja Bir Singh Naurangabad till Raja Sham Singh Attariwala arrived with his large, 7,000 strong army and the Khalsa had to retreat to Sialkot.[26] A few days later Major Ford, while communicating with the British office in Peshawar, was shot dead by one of the Sikhs.[26]

Revolt of Mandi[edit]

The Raja of Mandi was a very powerful man whose father was blessed by Guru Gobind Singh- and when R. Foulkes, an Irishman, and his army attacked the state the Sikhs were highly unsupportive of the war which caused them many casualties.[27] The Sikh troops put him on a log and roasted him alive for his treachery. Afterwards a Prussian, Henry Steinbach was sent a letter by Raja Attar Singh Sandhawalia where he was threatened to either leave the Punjab or be drowned in urine.[27] He clashed with Raja Attar Singh Sandhawalia near Rawalpindi, 1843, personally beating Sandhawalia with a baton after capturing him. Another French officer named Mouton was also a suspect although he was spared, he later fought in the First Anglo-Sikh War alongside the Sikh Khalsa Army.[27]

Khalsa Revivalism[edit]

A man who came to the forefront of Sikh revivalism was one Maharaja Bir Singh Naurangabad, a retired soldier turned ascetic who had set up his own gurdwara at village Naurangabad on the Sutlej and was the head of the Bhai Daya Singh Samparda also known as the Rara Sahib Samparda.[28] In times of national crisis, Sikh soldiers and peasantry began to turn to Maharaja Bir Singh for guidance.[29] Attending the him was a volunteer army of 1,200 musket men and 3,000 horsemen. Over 1,500 pilgrims were fed in his kitchen every day.[30] Princes Pashaura Singh and Kashmira Singh took advantage of the state of unrest and proclaimed their right to the throne.[31] Hira Singh asked his uncle, Gulab Singh Dogra, to proceed against the recalcitrant princes at Sialkot.[32] Gulab Singh undertook the expedition with alacrity. (Sialkot adjoined his territory and could be annexed by him.) The princes put up stout resistance. After they were ejected from Sialkot, they toured through Majha and then joined Maharaja Bir Singh at Naurangabad.[30]

They whipped up anti-Dogra feeling in the army by pointing out that Hira Singh Dogra had virtually usurped the throne.[32] Hira Singh Dogra and Pandit Jalla along with Rani Jindan had together come up with a plan to destroy the Khalsa in the state.[26] The Sikh Khalsa Army was divided between two lines often changing in the times that passed. These were the Khalsa Panchayat and the Lahore Durbar who both were believed to be representing Sikhism, the former orthodox Sikhism whereas the latter aristocratic Sikhism.[20] The Lahore Durbar wanted the Sikhs to remain loyal through connecting the religion to their state although Maharaja Bir Singh of Naurangabad declined- by this point the Lahore Durbar stopped being called the Sarkar-I-Khalsa as the ruler (Rani Jindan for the most part) never openly confessed her religion and she had multiple affairs with Pandits and other noblemen in the court.[6] Combined the Khalsa Panchayat's army was around 20,000 Sikh soldiery whereas the Lahore Durbar had around 34,500 not including Jaghirdari forces.[6] The dislike of Europeans grew from the constant incursions from Britishers along with provocations, whereas the dislike for Dogras was mainly an upper-class phenomenon and the Khalsa Panchayat had multiple Dogra representatives including Mian Prithi Singh, Mian Pacchattar Singh and Mian Naurang Singh.[16]

Kalnal Gulab Singh Gupta, representative of the Khalsa Panchayat, said to Vakil Rai Gobind Jas the in the presence of the Durbar that the Sikhs were planning on crossing the Sutlej river and seating themselves on the throne of Delhi.[6] Jarnail Gurdit Singh Majithia said that the army having now got high pay was bent upon some great design to conquer India- although Rani Jindan prevented them.[6]

Sacking of Peshawar[edit]

When the Khalsa Panchayat heard of the area of Peshawar being given back to Kabul, Maharaja Bir Singh sent 2,000 mutineers to Hazara and Peshawar to control it.[33] Jarnail Paolo Avitable already had around 6,000 troops and went on a mass-recruitment spree, taking another 3,000 Pathans to fight them.[33] The Sikhs conquered Hazara although could not take back Peshawar due to the high concentration of troops.[33] The Sikhs looted the Munshees of Hazara on their way back to Santpura and stole around 2 million rupees worth of gold and silver along with their jewelry.[33]

Assassination of Mihan Singh[edit]

Kalnal Mihan Singh, the Governor of Kashmir, at the Shergarhi fort refused to make his payments to the Mazhabi Sikhs who were working for him in an insulting manner.[33][34] They decided to assassinate him and arrived at 9:00 on the next day with two cannons, and asked for the Adi Guru Granth and the Granthi Singh to leave the fort.[33] They obliged and let them leave, and afterwards the bombardment had started.[33][34] While Mihan Singh was hiding Naik Talok Singh Mazhabi had found and killed him on the spot.[33] When news of the revolt reached Lahore, Sheikh Imamuddin of Jalandhar was deputed to Kashmir.[33][34] Taking Gulab Singh Dogra with him, he went to put down the rebellion.[33] Talok Singh Mazhabi tried to rally the entire army behind him but failed.[33] In the end, only two hundred soldiers stood with him.[33] The battle was fierce and four thousand Dogra men were killed.[33] Some of the rebels ran towards the Punjab.[33] The Sheikh claimed victory and restored peace.[33][34]

Mir Mannu Masjid Incident[edit]

During the same time, in Mir Mannu's Masjid, which Muslims throughout India paid respects to, the Khalsa soldiers from Santpura attacked it and cremated Mir Mannu meaning that he could not enter Jannat (heaven).[35]

Battle of Naurangabad[edit]

Attar Singh Sandhawalia, whose hostile activities in British India had been the subject of many protests, crossed the Sutlej into Durbar territory and joined Maharaja Bir Singh at Naurangabad.[36] The princes Kashmira Singh and Pashaura Singh also left their estates for Naurangabad; Maharaja Bir Singh's camp became the centre of the Sikh revolt against Dogra dominance over the Punjab.[36] Maharaja Bir Singh tried to bring about a settlement.[36] Whilst the negotiations were going on, the impetuous Sandhawalia lost patience and killed one of the Durbar's emissaries.[36] The Durbar artillery blasted their camp, killing several hundred men including Attar Singh, Prince Kashmira Singh and Maharaja Bir Singh- the other side did not fire back as Maharaja Bir Singh believed the Sikhs on the other side were their brothers and family.[36] The Durbar's troops, though victorious, were filled with remorse.[36] They had soiled their hands with the blood of Maharajah Ranjit Singh's family and of a man looked upon as a religious saint.[36] The Sikhs involved in the massacre turned their wrath against the Dogras. Hira Singh Dogra assuaged their feelings by making offerings in the memory of Maharaja Bir Singh and announcing that he might accept conversion to Sikhism.[36] What really saved Hira Singh Dogra was a fresh wave of rumours that the British were ready to invade the Punjab.[36]

Aftermath of the Battle of Naurangabad[edit]

The Sikhs intensified their crusade against the Lahore Durbar and the Dogras.[37] Jean-Baptiste Ventura, a French general, had to seal himself in his home protected by three regiments of loyal soldiers, Claude Auguste Court, another foreigner, barely escaped with his life and fled to British India.[37] Avitabile had fled to Jalalabad under the protection of the Afghans, and Garrison Commander Sobha Singh was murdered for stationing his troops within the holy city of Amritsar.[37] In Lahore Jemadar Khushal Singh and Lehna Singh Majithia had to all barricade themselves in their homes in fear as there were rumours of them having British sympathies.[37] Rani Jindan also planned to assassinate Raja Lal Singh for accepting the Khalsa Panchayat as his sovereign instead of the Lahore Durbar, despite the previous scandals that they had which were now public.[37] Raja Tej Singh was also planned to be assassinated as he tried to end Dogra supremacy, this was known as the Parema Conspiracy and was planned by the British.[37] Sir Henry Fane, the British Commander-in-Chief was also beaten by Akali Baba Durga Singh Nihang with a baton and broke his jaw.[38]

Battle of Daska[edit]

Hira Singh Dogra was deeply distrusted by the Sikhs hence he turned to his uncle (Gulab Singh Dogra) for help.[16] Gulab Singh hurried down from Jammu with 7,000 Dogras.[39] The news of the descent of the hillmen incensed the Khalsa soldiers, who decided to arrest the chief minister and his priest, Pandit Jalla.[16] Hira Singh and Jalla took an escort of Dogras and fled the capital to Gurjanwala.[16] Khalsa troops caught up with the fleeing Dogra and his Brahmin mentor.[16] A running fight ensued in which over 1,000 Dogras were killed.[16] Hira Singh and Jalla were slain and their heads were impaled on spears and paraded through the streets of Lahore by the Sikhs in front of the palace of Rani Jindan.[16]

Sialkot Durbar[edit]

Pashaura Singh[edit]

The camps of the Sikh troops were a scene of commotion, the men declaring that they would have no ruler but Pashaura Singh, who would increase their pay and under whom they would conquer Jasrota and Jammu. They declared that the Rani and her brother, the Vazir, were unfit to govern, and that the Sardars of the council and their officers did nothing but get Jagirs themselves, while they (the private soldiers) were resolved to have no ruler who did not increase their pay.[40]

Raja Gulab Singh Dogra showed calculated indifference to the summons to appear before the court, stating that he was the servant of the Khalsa Panchayat and not of the Lahore Durbar and that he would only answer to the Panches.[41] He joined the faction of Raja Lal Singh and became his brother-in-arms by exchanging swords with him. Prince Pashaura Singh returned to the Punjab and set up a rival court at Sialkot.[40] This was a signal for lawless elements to rise, Jathas of Nihangs roamed about the Majha country and threatened to loot Amritsar and Lahore.[40] Rani Jindan tried to win over the families of powerful chieftains to her son's side against the pretensions of Pashaura Singh and to help restore law and order in the state.[16] She broke off Maharaja Duleep Singh's engagement with the comparatively poor Nakkais and betrothed him to the daughter of Chattar Singh Attariwala.[16] This did not deter Prince Pashaura Singh.[16] He captured the fort of Attock, proclaimed himself Maharaja, and approached the Afghans for help Chattar Singh Attariwala proceeded to Attock.[16]

Pashaura Singh accepted the assurance of personal safety from Chattar Singh Attariwala and agreed to accompany him to the capital.[42] Twenty miles from Attock, the prince was seized, brought back to the fort, and murdered.[42] The Panches discovered that the army had once again been used by one Durbar faction against another.[42] They felt that the murder of Pashaura Singh had been master-minded by Rani Jindan's brother, Vazir Jawahar Singh, and ordered him to appear before the Khalsa Panchayat under the five students of Maharaja Bir Singh- the Panj Pyare- Maharaja Nihal Singh (also known as Maharaj Singh),[43] Bhai Suraj Singh, Baba Bikram Singh Bedi, Baba Sujan Singh, Baba Khem Singh and Baba Kahn Singh who were the commanders of the Regiment which was a part of the Battle of Naurangabad on the side of Raja Hira Singh Dogra.[44][16]

Assassination of Vazir Jawahir Singh[edit]

To avenge the deaths of the saint of Naurangabad and the family of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, on the evening of September 21, 1845, the terrified Jawahar Singh was summoned to the vivid Khalsa Panchayat.[45] He clutched the infant Maharaja Duleep Singh to his bosom and rode out on his elephant to answer the summons of the Panchayat.[45] Rani Jindan and her maid servant Mangla followed with their escort.[45] At the cantonment, Vazir Jawahar Singh refused to alight from his elephant.[45] The guards plucked the Maharaja from his lap and speared Jawahar Singh where he sat in the howdah.[16] Next morning the minister's corpse was cremated.[16] His four wives, who committed Sati, despite the Khalsa's warning against it, died cursing the Khalsa and prophesying that the wives of Sikh soldiers would soon be widowed and the Punjab laid desolate.[16] Jindan returned to the palace screaming vengeance against the Khalsa Panchayat.[16] Rani Jindan met with the Panj Pyare and told them that she would self immolate herself and the infant for the treason committed- they curtly replied that they would organize it happily.[46]

The army Panchayat took over the affairs of state and became the sovereign of the Punjab. It selected Diwan Dina Nath to act as its mouthpiece and issued instructions that no letter was to be issued to the English till the Panches had deliberated on its contents.[47] The Panchayat acted in the name of the Khalsa.[47] Its orders were issued under the seal "Akal Sahai, Panth Khalsa Jio".[48] The British were much exercised by what seemed to them to be a change in the form of government.[47] It was noticed that the term Sarbatt Khalsa had been introduced in the official correspondence of the Durbar since the death of Maharajah Sher Singh and as the army council gained power at the expense of the palace coterie, expressions like Sarbatt Khalsaji and Khalsa Panth came into vogue.[49] The British agent was instructed to make it clear that his government would recognize no other form of government save a monarchy and regarded “the army with its self-constituted Panchayats in no other light than as the subjects and servants of the government.”[50]

Aftermath[edit]

The Panchayati Revolution came to an end right once the First Anglo-Sikh War started and the Khalsa Panchayat joined the Lahore Durbar in fighting the British- except that the Lahore Durbar under Rani Jindan wished for the Khalsa Panth to be eradicated and cooperated with the British to make sure that it would happen.[51]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Baba Bir Singh - SikhiWiki, free Sikh encyclopedia". www.sikhiwiki.org. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ Sheikh, Majid (2016-04-10). "'Teja' the traitor who became Raja of Sialkot". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel Henry (1890). The Panjab Chiefs: Historical and Biographical Notices of the Principal Families in the Lahore and Rawalpindi Divisions of the Panjab.

- ^ a b Singh, Khushwant (2014-07-15). The Fall of the Kingdom of Punjab. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-796-7.

- ^ Nalwa, Vanit (2009). Hari Singh Nalwa, "champion of the Khalsaji" (1791-1837). Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-785-5.

- ^ a b c d e Gupta Hari Ram. The Department Of History Panjab University. 1956.

- ^ a b c d e Sikh Digital Library. Soldierly Traditions Of The Sikhs - Dr. Hari Ram Gupta. Sikh Digital Library. Sikh Digital Library.

- ^ a b c Hasrat, Bikrama Jit (1968). Anglo-Sikh Relations, 1799-1849: A Reappraisal of the Rise and Fall of the Sikhs. local stockists: V. V. Research Institute Book Agency.

- ^ Grewal, J. S. (2004). The Khalsa: Sikh and Non-Sikh Perspectives. Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-580-6.

- ^ Banerjee, Anil Chandra (1985). The Khalsa Raj. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-0-8364-1355-7.

- ^ The Sikh Review. Sikh Cultural Centre. 2010.

- ^ a b c d Prasad, Bisheshwar (1968). Ideas in History: Proceedings. Asia Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-210-98190-0.

- ^ Suri (Lala), Sohan Lal (1961). Umdat-ut-tawarikh ... S. Chand.

- ^ "Dhian Singh", Wikipedia, 2023-10-11, retrieved 2023-11-15

- ^ Domin, Dolores (1977). India in 1857-59: A Study in the Role of the Sikhs in the People's Uprising. Akademie-Verlag.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Khushwant Singh (1966). A HIstory Of The Sikhs, Vol. 2: 1839-1964. Public Resource. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Broadfoot, William (1888). The Career of Major George Broadfoot, C. B. ...: In Afghanistan and the Punjab. J. Murray.

- ^ Broadfoot, William (2017-08-19). The Career of Major George Broadfoot, C. B. ...: In Afghanistan and the Punjab. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-1-375-46808-4.

- ^ R.E.), William BROADFOOT (Major (1888). The Career of Major George Broadfoot, C.B. ... in Afghanistan and the Punjab. Compiled from His Papers and Those of Lords Ellenborough and Hardinge. By ... W. Broadfoot. With Portrait and Maps. London.

- ^ a b Broadfoot, George; Broadfoot, William; of, Edward Law Ellenborough, earl; Visount, Henry Hardinge Hardinge, 1st (1888). The Career of Major George Broadfoot, C.B. ... in Afghanistan and the Punjab, Compiled from His Papers and Those of Lords Ellenborough and Hardinge, by Major W. Broadfoot. J. Murray.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Low, D. A. (1991-06-18). Political Inheritance of Pakistan. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-11556-3.

- ^ a b "https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-897ddef31dc71af5e5030b164c57a84a-lq".

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Grewal, Dr Dalvinder Singh. Eminent Grewals. Archers & Elevators Publishing House. ISBN 978-93-94958-60-9.

- ^ Bansal, Bobby Singh (2015-12-01). Remnants of the Sikh Empire: Historical Sikh Monuments in India & Pakistan. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-93-84544-93-5.

- ^ Rai, Rajesh; Reeves, Peter (2008-07-25). The South Asian Diaspora: Transnational networks and changing identities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-10594-6.

- ^ a b c d e "Sacking of Porothar". Quora.

- ^ a b c "Revolt of Mandi and Kulu". Quora.

- ^ Dilagīra, Harajindara Siṅgha (1997). The Sikh Reference Book. Sikh Educational Trust for Sikh University Centre, Denmark. ISBN 978-0-9695964-2-4.

- ^ "NAURANGABAD - The Sikh Encyclopedia". 2000-12-19. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ a b "Contrition prayer offered at Akal Takht for Baba Bir Singh's murder 176 years ago". The Times of India. 2020-10-11. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ "The Sunday Tribune - Spectrum".

- ^ a b Kaur-Nagpal, Unknown artist Presumably photographed by Upneet, English: Mural depicting the spiritual lineage and associates of Baba Bir Singh Naurangabad's Dera (sanctuary), circa mid-19th century., retrieved 2023-11-16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Sacking of Peshawar and Jammu". Quora.

- ^ a b c d Singh, Nidhan (2022-05-24). "Recollections of a Sikh warrior: The tales of Nihang Hardit Singh". The Khalsa Chronicle. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ "https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-0296898a3ef8f23819b155a2ad828c35-lq".

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d e f g h i "Battle of Sialkot". Quora.

- ^ a b c d e f "Aftermath of the Battle of Sialkot". Quora.

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1978). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Lion of Lahore, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, 1799-1839. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-81-215-0515-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c "PASHAURA SINGH, KANVAR - The Sikh Encyclopedia". 2000-12-19. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ "Pashaura Singh, Kanwar - Gateway To Sikhism". www.allaboutsikhs.com. 2007-03-22. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ a b c Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2016). Kohinoor: The Story of the WorldÕs Most Infamous Diamond. Juggernaut Books. ISBN 978-93-86228-08-6.

- ^ "Bhai Maharaj Singh - SikhiWiki, free Sikh encyclopedia". www.sikhiwiki.org. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ Anand, Anita (2015-01-15). Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-3546-3.

- ^ a b c d Grewal, J. S. (8 October 1998). https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/The_Sikhs_of_the_Punjab/2_nryFANsoYC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=pashaura+singh+prince&pg=PA122&printsec=frontcover. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521637640.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Talbot, Ian (2013-12-16). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-79029-4.

- ^ a b c Gandhi, Rajmohan (2000-10-14). Revenge and Reconciliation: Understanding South Asian History. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-318-9.

- ^ Suri (lala), Sohan Lal (1961). pts.1-5.Chronicle of the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, 1831-1839 A.D. S. Chand.

- ^ Gill, Tarlochan Singh (1996). History of the Sikhs. Canada Centre Publications.

- ^ Singh, Dr Nazer (2021-09-15). GoldenTemple and the Punjab Historiography. K.K. Publications.

- ^ "How Maharaja Ranjit Singh's wife escaped British prison, led two wars". Hindustan Times. 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

Works cited[edit]

- Allen, Charles (2001). Soldier Sahibs. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11456-9.

- Cunningham, Joseph (1853). Cunningham's history of the Sikhs. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Farwell, Byron (1973). Queen Victoria's little wars. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-216-6.

- Featherstone, Donald (2007). At Them with the Bayonet: The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845-1846. Leonnaur Books.

- Grewal, J. S. (1998). The Sikhs of Punjab. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26884-4.

- Hernon, Ian (2003). Britain's forgotten wars. Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-3162-5.

- Jawandha, Nahar (2010). Glimpses of Sikhism. New Delhi: Sanbun Publishers. ISBN 978-93-80213-25-5.

- Sidhu, Amarpal (2010). The First Anglo-Sikh War. Stroud, Gloucs: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84868-983-1.

- Smith, David (2019). The First Anglo-Sikh War 1845–46: The betrayal of the Khalsa. Osprey Publishing; Osprey Campaign Series #338. ISBN 978-1-4728-3447-8.

External links[edit]

- World History Encyclopedia - First Anglo-Sikh War

- First Anglo-Sikh War Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Anglo-Sikh Wars

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (November 2023) |

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (November 2023) |

KSF

KSF