Panthera

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

| Panthera Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

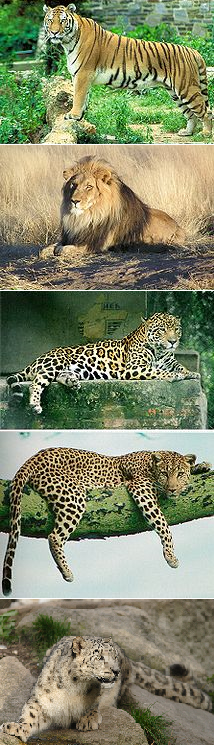

| From top to bottom: tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, snow leopard | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera Oken, 1816[2] |

| Type species | |

| Felis pardus (= Panthera pardus) | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Panthera[note 1] is a genus within the family Felidae, and one of two extant genera in the subfamily Pantherinae. It contains the largest living members of the cat family. There are five living species: the jaguar, leopard, lion, snow leopard and tiger. Numerous extinct species are also named, including the cave lion and American lion.

Etymology

[edit]The word panther derives from Classical Latin panthēra, itself from the Ancient Greek pánthēr (πάνθηρ).[5]

Characteristics

[edit]In Panthera species, the dorsal profile of the skull is flattish or evenly convex. The frontal interorbital area is not noticeably elevated, and the area behind the elevation is less steeply sloped. The basic cranial axis is nearly horizontal. The inner chamber of the bullae is large, the outer small. The partition between them is close to the external auditory meatus. The convexly rounded chin is sloping.[6] All Panthera species have an incompletely ossified hyoid bone and a specially adapted larynx with large vocal folds covered in a fibro-elastic pad; these characteristics enable them to roar. Only the snow leopard cannot roar, as it has shorter vocal folds of 9 mm (0.35 in) that provide a lower resistance to airflow; it was therefore proposed to be retained in the genus Uncia.[7] Panthera species can prusten, which is a short, soft, snorting sound; it is used during contact between friendly individuals. The roar is an especially loud call with a distinctive pattern that depends on the species.[8]

Evolution

[edit]The geographic origin of the genus Panthera is uncertain, though the earliest known definitive species Panthera principialis is from Tanzania.[9] P. blytheae from northern Central Asia, originally described as the oldest known Panthera species, is suggested to be similar in skull features to the snow leopard,[10] but subsequent studies have since agreed that it is not a member of or a related species of the snow leopard lineage and that it belongs to a different genus Palaeopanthera.[11][12][13] The tiger, snow leopard, and clouded leopard genetic lineages likely dispersed in Southeast Asia during the Late Miocene.[10] Genetic studies indicate that the pantherine cats diverged from the subfamily Felinae between six and ten million years ago.[14] The genus Neofelis is sister to Panthera.[14][15][16][17] The clouded leopard appears to have diverged about 8.66 million years ago. Panthera diverged from other cat species about 11.3 million years ago and then evolved into the species tiger about 6.55 million years ago, snow leopard about 4.63 million years ago and leopard about 4.35 million years ago. Mitochondrial sequence data from fossils suggest that the American lion (P. atrox) is a sister lineage to Panthera spelaea (the Eurasian cave or steppe lion) that diverged about 0.34 million years ago, and that both P. atrox and P. spelaea are most closely related to lions among living Panthera species.[18] The snow leopard is nested within Panthera and is the sister species of the tiger.[19]

Results of a 2016 study based on analysis of biparental nuclear genomes suggest the following relationships of living Panthera species:[20]

The extinct species Panthera gombaszogensis, was probably closely related to the modern jaguar. The first fossil remains were excavated in Olivola, in Italy, and date to 1.6 million years ago.[21] Fossil remains found in South Africa that appear to belong within the Panthera lineage date to about 2 to 3.8 million years ago.[22]

Classification

[edit]Panthera was named and described by Lorenz Oken in 1816 who placed all the spotted cats in this group.[23][24] During the 19th and 20th centuries, various explorers and staff of natural history museums suggested numerous subspecies, or at times called "races", for all Panthera species. The taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed skins and skulls in the zoological collection of the Natural History Museum, London, and grouped subspecies described, thus shortening the lists considerably.[25][26][27] Reginald Innes Pocock revised the classification of this genus in 1916 as comprising the tiger (P. tigris), lion (P. leo), jaguar (P. onca), and leopard (P. pardus) on the basis of common features of their skulls.[28] Since the mid-1980s, several Panthera species became subjects of genetic research, mostly using blood samples of captive individuals. Study results indicate that many of the lion and leopard subspecies are questionable because of insufficient genetic distinction between them.[29][30] Subsequently, it was proposed to group all African leopard populations to P. p. pardus and retain eight subspecific names for Asian leopard populations.[31] Results of genetic analysis indicate that the snow leopard (formerly Uncia uncia) also belongs to the genus Panthera (P. uncia), a classification that was accepted by IUCN Red List assessors in 2008.[14][32]

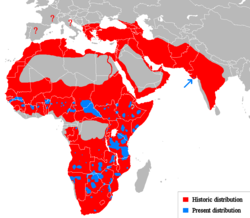

Based on genetic research, it was suggested to group all living sub-Saharan lion populations into P. l. leo.[33] Results of phylogeographic studies indicate that the Western and Central African lion populations are more closely related to those in India and form a different clade than lion populations in Southern and East Africa; southeastern Ethiopia is an admixture region between North African and East African lion populations.[34][35]

Black panthers do not form a distinct species, but are melanistic specimens of the genus, most often encountered in the leopard and jaguar.[36][37]

Contemporary species

[edit]The following list of the genus Panthera is based on the taxonomic assessment in Mammal Species of the World and reflects the taxonomy revised in 2017 by the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group:[2][38]

| Species | Subspecies | IUCN Red List status and distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Lion P. leo (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] | P. l. leo (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] including:

P. l. melanochaita (Smith, 1842)[41] including: |

VU[43] |

| Jaguar P. onca (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] | Monotypic[44][38] | NT[45] |

| Leopard P. pardus (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] | African leopard P. p. pardus (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] Indian leopard P. p. fusca (Meyer, 1794)[46] |

VU[56] |

| Tiger P. tigris (Linnaeus, 1758)[39] | P. t. tigris (Linnaeus, 1758) including:

Sunda Island tiger P. t. sondaica Temminck, 1844)[58] including

|

EN[63] |

| Snow leopard P. uncia[38] (Schreber, 1775)[64] | Monotypic[38] | VU[32] |

Extinct species and subspecies

[edit]| Species and subspecies | Fossil records | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panthera atrox | North America, 0.13 to 0.013 MYA, with dubious remains in South America.[65] | Commonly known as the American lion, P. atrox is thought to have descended from a basal P. spelaea cave lion population isolated south of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, and then established a mitochondrial sister clade circa 200,000 BP.[66] It was sometimes considered a subspecies either under the nomenclature of P. leo[66] or P. spelaea.[67] One of the largest Panthera species.[68] Became extinct around 13,000-12,000 years ago.[69] |  |

| Panthera balamoides[70] | Mexico, ~0.13 MYA | Dubious, other authors suggest that the remains are actually of the extinct bear Arctotherium instead.[71] | |

| Panthera fossilis[72] | Europe and Asia, 0.68 to 0.25 MYA | Extinct species of lion known from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Asia. One of the largest known species of Panthera. Considered to be the ancestor of P. spelaea.[73] |  |

| Panthera gombaszogensis | Europe, possibly Asia and Africa, 2.0 to 0.35 MYA | Ranged across Europe, as well as possibly Asia and Africa from around 2 million to 350,000 years ago.[74] Often suggested to be the ancestor of the living jaguar (Panthera onca), and sometimes referred to as the "European jaguar". Panthera schreuderi and Panthera toscana are considered junior synonyms of P. gombaszogensis. It is occasionally classified as a subspecies of P. onca.[75][76] |  |

| Panthera palaeosinensis | Northern China, ~3 MYA | Initially thought to be an ancestral tiger species, but several scientists place it close to the base of the genus Panthera[1] At least three recent studies considered Panthera zdanskyi likely to be a synonym of P. palaeosinensis.[77][78][79] | |

| Panthera principialis | Tanzania, ~3.7 MYA | Described in 2023.[9] | |

| Panthera shawi | Laetoli site in Tanzania, ~3 MYA | A leopard-like cat[80] | |

| Panthera spelaea | Much of Eurasia, 0.6 to 0.013 MYA[81] | Commonly known as the cave lion or steppe lion. Originally spelaea was classified as a subspecies of the extant lion P. leo.[82] Results of recent genetic studies indicate that it belongs to a distinct species, namely P. spelaea that is most closely related to the modern lion among living Panthera species.[83][84] Other genetic results indicate that P. fossilis also warrants status as a species.[85][86] It became extinct around 14,500-14,000 years ago.[87] |  |

| Panthera youngi[88] | China, Japan, ~0.35 MYA |  | |

| Panthera zdanskyi | Gansu province of northwestern China, 2.55 to 2.16 MYA | It was initially considered to be a close relative of the tiger.[1] But it is possibly synonymous with P. palaeosinensis.[9][89] |  |

| Panthera leo sinhaleyus | Sri Lanka | This lion subspecies was described on the basis of two teeth.[90] | |

| Panthera onca augusta[91] | North America | May have lived in temperate forests across North America[92] | |

| Panthera onca mesembrina[93] | South America | May have lived in grasslands in South America, unlike the modern jaguar |  |

| Panthera pardus spelaea | Europe | Closely related to Asiatic leopard subspecies,[94] |  |

| Panthera tigris acutidens | Much of Asia | Not closely related to modern tiger subspecies[95] | |

| Panthera tigris soloensis | Java, Indonesia | Not closely related to modern tiger subspecies[95] | |

| Panthera tigris trinilensis | Java, Indonesia | Not closely related to modern tiger subspecies[95] |

Other, now invalid, species have also been described, such as Panthera crassidens from South Africa, which was later found to be based on a mixture of leopard and cheetah fossils.[96] A "Panthera dhokpathanensis" was briefly referenced in 1986 in a report on apparent new carnivorans from the Dhok Patha region in the Siwaliks, but as no description was provided this name is a nomen nudum.[97]

Phylogeny

[edit]

In 2018, results of a phylogenetic study on living and fossil cats were published. This study was based on the morphological diversity of the mandibles of saber-toothed cats, their speciation and extinction rates.[99]

| Panthera |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mazák, J. H.; Christiansen, P.; Kitchener, A. C. (2011). "Oldest Known Pantherine Skull and Evolution of the Tiger". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625483M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3189913. PMID 22016768.

- ^ a b c d Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Genus Panthera". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 546–548. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Panthera". Collins Dictionary. Penguin Random House. 2005.

- ^ Eons 2021, 1:30, spoken by Kallie Moore

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "πάνθηρ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera". The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 196–239.

- ^ Hast, M. H. (1989). "The larynx of roaring and non-roaring cats". Journal of Anatomy. 163: 117–121. PMC 1256521. PMID 2606766.

- ^ Weissengruber, G. E.; Forstenpointner, G.; Peters, G.; Kübber-Heiss, A.; Fitch, W. T. (2002). "Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and the domestic cat (Felis silvestris f. catus)". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00088.x. PMC 1570911. PMID 12363272.

- ^ a b c Hemmer, H. (2023). "The identity of the "lion", Panthera principialis sp. nov., from the Pliocene Tanzanian site of Laetoli and its significance for molecular dating the pantherine phylogeny, with remarks on Panthera shawi (Broom, 1948), and a revision of Puma incurva (Ewer, 1956), the Early Pleistocene Swartkrans "leopard" (Carnivora, Felidae)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 103 (2): 465–487. Bibcode:2023PdPe..103..465H. doi:10.1007/s12549-022-00542-2.

- ^ a b Tseng, Z.J.; Wang, X.; Slater, G.J.; Takeuchi, G.T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. & Xie, G. (2014). "Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1774): 20132686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2686. PMC 3843846. PMID 24225466.

- ^ Geraads, D.; Peigné, S (2017). "Re-appraisal of Felis pamiri Ozansoy 1959 (Carnivora, Felidae) from the upper Miocene of Turkey: the earliest pantherine cat?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 24 (4): 415–425. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9349-6. S2CID 207195894.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (2023). "The evolution of the palaeopantherine cats, Palaeopanthera gen. nov. blytheae (Tseng et al., 2014) and Palaeopanthera pamiri (Ozansoy, 1959) comb. nov. (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 103 (4): 827–839. Bibcode:2023PdPe..103..827H. doi:10.1007/s12549-023-00571-5. S2CID 257842190.

- ^ Jiangzuo, Q.; Madurell-Malapeira, J.; Li, X.; Estraviz-López, D.; Mateus, O.; Testu, A.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Deng, T. (2025). "Insights on the evolution and adaptation toward high-altitude and cold environments in the snow leopard lineage". Science Advances. 11 (3): eadp5243. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adp5243. PMC 11734717. PMID 39813339.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S.J. (2006). "The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146. S2CID 41672825. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Janczewski, D.N.; Modi, W.S.; Stephens, J.C. & O'Brien, S.J. (1996). "Molecular evolution of mitochondrial 12S RNA and cytochrome b sequences in the pantherine lineage of Felidae". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (4): 690–707. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040232. PMID 7544865.

- ^ Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S.J. (1997). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (S1): S98 – S116. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018. S2CID 40185850. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Yu, L. & Zhang, Y.P. (2005). "Phylogenetic studies of pantherine cats (Felidae) based on multiple genes, with novel application of nuclear beta-fibrinogen intron 7 to carnivores". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (2): 483–495. Bibcode:2005MolPE..35..483Y. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.01.017. PMID 15804417.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Shapiro, B.; Barnes, I.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Burger, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Higham, T.F.G.; Wheeler, H.T.; Rosendahl, W.; Sher, A.V.; Sotnikova, M.; Kuznetsova, T.; Baryshnikov, G.F.; Martin, L.D.; Harington, C.R.; Burns, J.A. & Cooper, A. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.1668B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b Davis, B.W.; Li, G.; Murphy, W.J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64–76. Bibcode:2010MolPE..56...64D. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224.

- ^ Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E. & Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMC 4691742. PMID 26518481.

- ^ Hemmer, H.; Kahlke, R.D. & Vekua, A.K. (2001). "The Jaguar – Panthera onca gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938) (Carnivora: Felidae) in the late lower Pleistocene of Akhalkalaki (south Georgia; Transcaucasia) and its evolutionary and ecological significance". Geobios. 34 (4): 475–486. Bibcode:2001Geobi..34..475H. doi:10.1016/s0016-6995(01)80011-5.

- ^ Turner, A. (1987). "New fossil carnivore remains from the Sterkfontein hominid site (Mammalia: Carnivora)". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 34 (15): 319–347.

- ^ Oken, L. (1816). "1. Art, Panthera". Lehrbuch der Zoologie. 2. Abtheilung. Jena: August Schmid & Comp. p. 1052.

- ^ Allen, J. A. (1902). "Mammal names proposed by Oken in his 'Lehrbuch der Zoologie'" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 16 (27): 373−379. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The panthers and ounces of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34 (1): 65–82.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1932). "The leopards of Africa". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 102 (2): 543–591. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1932.tb01085.x.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1939). "The races of jaguar (Panthera onca)". Novitates Zoologicae. 41: 406–422.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1916). "The Classification and Generic Nomenclature of F. uncia and its Allies". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Including Zoology, Botany, and Geology. Series 8. XVIII (105): 314–316. doi:10.1080/00222931608693854.

- ^ O'Brien, S. J.; Martenson, J. S.; Packer, C.; Herbst, L.; de Vos, V.; Joslin, P.; Ott-Joslin, J.; Wildt, D. E. & Bush, M. (1987). "Biochemical genetic variation in geographic isolates of African and Asiatic lions" (PDF). National Geographic Research. 3 (1): 114–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013.

- ^ Miththapala, S.; Seidensticker, J.; O'Brien, S. J. (1996). "Phylogeographic subspecies recognition in leopards (Panthera pardus): Molecular genetic variation". Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 1115–1132. Bibcode:1996ConBi..10.1115M. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041115.x.

- ^ Uphyrkina, O.; Johnson, W. E.; Quigley, H. B.; Miquelle, D. G.; Marker, L.; Bush, M. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2001). "Phylogenetics, genome diversity and origin of modern leopard, Panthera pardus". Molecular Ecology. 10 (11): 2617–2633. Bibcode:2001MolEc..10.2617U. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01350.x. PMID 11883877. S2CID 304770. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ a b McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D.; Jackson, R.; Zahler, P. & McCarthy, K. (2017). "Panthera uncia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22732A50664030. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T22732A50664030.en. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ Dubach, J.; Patterson, B. D.; Briggs, M. B.; Venzke, K.; Flamand, J.; Stander, P.; Scheepers, L.; Kays, R. W. (2005). "Molecular genetic variation across the southern and eastern geographic ranges of the African lion, Panthera leo". Conservation Genetics. 6 (1): 15–24. Bibcode:2005ConG....6...15D. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7729-6. S2CID 30414547. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N.; De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. Bibcode:2011JBiog..38.1356B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. S2CID 82728679. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ Bertola, L. D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K. J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P. A.; Driscoll, C. A.; Tende, T. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- ^ Robinson, R. (1970). "Inheritance of black form of the leopard Panthera pardus". Genetica. 41 (1): 190–197. doi:10.1007/bf00958904. PMID 5480762. S2CID 5446868.

- ^ Eizirik, E.; Yuhki, N.; Johnson, W. E.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Hannah, S. S.; O'Brien, S. J. (2003). "Molecular Genetics and Evolution of Melanism in the Cat Family". Current Biology. 13 (5): 448–453. Bibcode:2003CBio...13..448E. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00128-3. PMID 12620197. S2CID 19021807.

- ^ a b c d Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66−75. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. pp. 41−42.

- ^ Meyer, J. N. (1826). Dissertatio inauguralis anatomico-medica de genere felium (Doctoral thesis). Vienna: University of Vienna.

- ^ Smith, C. H. (1842). "Black maned lion Leo melanochaitus". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 177.

- ^ Mazak, V. (1975). "Notes on the Black-maned Lion of the Cape, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) and a Revised List of the Preserved Specimens". Verhandelingen Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (64): 1–44.

- ^ Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15951A115130419.

- ^ Larson, S. E. (1997). "Taxonomic re-evaluation of the jaguar". Zoo Biology. 16 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1997)16:2<107::AID-ZOO2>3.0.CO;2-E.

- ^ Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R. & Harmsen, B. (2017). "Panthera onca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15953A123791436.

- ^ Meyer, F. A. A. (1794). "Über de la Metheries schwarzen Panther". Zoologische Annalen. Erster Band. Weimar: Im Verlage des Industrie-Comptoirs. pp. 394–396.

- ^ Cuvier, G. (1809). "Recherches sur les espėces vivantes de grands chats, pour servir de preuves et d'éclaircissement au chapitre sur les carnassiers fossils". Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. Tome XIV: 136–164.

- ^ Hemprich, W.; Ehrenberg, C. G. (1830). "Felis, pardus?, nimr". In Dr. C. G. Ehrenberg (ed.). Symbolae Physicae, seu Icones et Descriptiones Mammalium quae ex Itinere per Africam Borealem et Asiam Occidentalem Friderici Guilelmi Hemprich et Christiani Godofredi Ehrenberg. Decas Secunda. Zoologica I. Mammalia II. Berolini: Officina Academica. pp. Plate 17.

- ^ Valenciennes, A. (1856). "Sur une nouvelles espèce de Panthère tué par M. Tchihatcheff à Ninfi, village situé à huit lieues est de Smyrne". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences. 42: 1035–1039.

- ^ Satunin, K. A. (1914). Opredelitel' mlekopitayushchikh Rossiiskoi Imperii [Guide to the mammals of the Russian Empire]. Tiflis: Tipographia Kantzelyarii Namestnichestva.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1927). "Description of two subspecies of leopards". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 9. 20 (116): 213–214. doi:10.1080/00222932708655586.

- ^ Schlegel, H. (1857). "Felis orientalis". Handleiding Tot de Beoefening der Dierkunde, Ie Deel. Breda: Boekdrukkerij van Nys. p. 23.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1862). "Description of some new species of Mammalia". Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society of London. 30: 261−263, plate XXXIII. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1862.tb06524.x.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The Panthers and Ounces of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34 (2): 307–336.

- ^ Deraniyagala, P. E. P. (1956). "The Ceylon leopard, a distinct subspecies". Spolia Zeylanica. 28: 115–116.

- ^ Stein, A. B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro, S.; Kamler, J. F. & Laguardia, A. (2016). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15954A102421779.

- ^ Illiger, C. (1815). "Überblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verteilung über die Welttheile". Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. 1804−1811: 39−159. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Temminck, C. J. (1844). "Aperçu général et spécifique sur les Mammifères qui habitent le Japon et les Iles qui en dépendent". In Siebold, P. F. v.; Temminck, C. J.; Schlegel, H. (eds.). Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium, quae in itinere per Japoniam, jussu et auspiciis superiorum, qui summum in India Batava imperium tenent, suscepto, annis 1825–1830 collegit, notis, observationibus et adumbrationibus illustravit Ph. Fr. de Siebold. Leiden: Lugduni Batavorum.

- ^ Hilzheimer, M. (1905). "Über einige Tigerschädel aus der Straßburger zoologischen Sammlung". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 28: 594–599.

- ^ Mazák, V. (1968). "Nouvelle sous-espèce de tigre provenant de l'Asie du sud-est". Mammalia. 32 (1): 104−112. doi:10.1515/mamm.1968.32.1.104. S2CID 84054536.

- ^ Luo, S. J.; Kim, J. H.; Johnson, W. E.; Walt, J. v. d.; Martenson, J.; Yuhki, N.; Miquelle, D. G. (2004). "Phylogeography and Genetic Ancestry of Tigers (Panthera tigris)". PLOS Biology. 2 (12): e442. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442. PMC 534810. PMID 15583716.

- ^ Schwarz, E. (1912). "Notes on Malay tigers, with description of a new form from Bali". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 8 Volume 10 (57): 324–326. doi:10.1080/00222931208693243.

- ^ Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y. & Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

- ^ Schreber, J. C. D. (1777). "Die Unze". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Wolfgang Walther. pp. 386–387.

- ^ Chimento, N. R.; Agnolin, F. L. (2017). "The fossil American lion (Panthera atrox) in South America: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (8): 850–864. Bibcode:2017CRPal..16..850C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.009. hdl:11336/65990.

- ^ a b Barnett, R.; Shapiro, B.; Barnes, I.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Burger, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Higham, T. F. G.; Wheeler, H. T.; Rosendahl, W. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity". Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–77. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.1668B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Sotnikova, M.; Nikolskiy, P. (2006). "Systematic position of the cave lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss) based on cranial and dental characters" (PDF). Quaternary International. 142–143: 218–228. Bibcode:2006QuInt.142..218S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2005.03.019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Christiansen, P.; Harris, J. M. (2009). "Craniomandibular morphology and phylogenetic affinities of Panthera atrox: implications for the evolution and paleobiology of the lion lineage". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 934–945. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29..934C. doi:10.1671/039.029.0314. S2CID 85975640.

- ^ O’Keefe, F. Robin; Dunn, Regan E.; Weitzel, Elic M.; Waters, Michael R.; Martinez, Lisa N.; Binder, Wendy J.; Southon, John R.; Cohen, Joshua E.; Meachen, Julie A.; DeSantis, Larisa R. G.; Kirby, Matthew E.; Ghezzo, Elena; Coltrain, Joan B.; Fuller, Benjamin T.; Farrell, Aisling B. (18 August 2023). "Pre–Younger Dryas megafaunal extirpation at Rancho La Brea linked to fire-driven state shift". Science. 381 (6659): eabo3594. doi:10.1126/science.abo3594. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 37590347. S2CID 260956289. Archived from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Stinnesbeck, S. R.; Stinnesbeck, W.; Frey, E.; Olguín, J. A.; Sandoval, C. R.; Morlet, A. V.; González, A. H. (2018). "Panthera balamoides and other Pleistocene felids from the submerged caves of Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 32 (7): 1–10. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1556649. S2CID 92328512.

- ^ Blaine W. Schubert; James C. Chatters; Joaquin Arroyo-Cabrales; Joshua X. Samuels; Leopoldo H. Soibelzon; Francisco J. Prevosti; Christopher Widga; Alberto Nava; Dominique Rissolo; Pilar Luna Erreguerena (2019). "Yucatán carnivorans shed light on the Great American Biotic Interchange". Biology Letters. 15 (5) 20190148. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2019.0148. PMC 6548739. PMID 31039726.

- ^ Harington, C. R. (1996). Pleistocene mammals of the Yukon Territory (PhD). Edmonton: University of Alberta.

- ^ Sabo, Martin; Tomašových, Adam; Gullár, Juraj (August 2022). "Geographic and temporal variability in Pleistocene lion-like felids: Implications for their evolution and taxonomy". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25 (2): 1–27. doi:10.26879/1175. ISSN 1094-8074. S2CID 251855356. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Marciszak, A. (2014). "Presence of Panthera gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938) in the late Middle Pleistocene of Biśnik Cave, Poland, with an overview of Eurasian jaguar size variability". Quaternary International. 326–327: 105–113. Bibcode:2014QuInt.326..105M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.12.029.

- ^ Hemmer, H.; Kahlke, R. D.; Vekua, A. K. (2010). "Panthera onca georgica ssp. nov. from the Early Pleistocene of Dmanisi (Republic of Georgia) and the phylogeography of jaguars (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 257 (1): 115–127. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0067.

- ^ Mol, D.; van Logchem, W.; de Vos, J. (2011). "New record of the European jaguar, Panthera onca gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938), from the Plio-Pleistocene of Langenboom (The Netherlands)". Cainozoic Research. 8 (1–2): 35–40. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Hemmer, Helmut (2023). "The identity of the "lion", Panthera principialis sp. nov., from the Pliocene Tanzanian site of Laetoli and its significance for molecular dating the pantherine phylogeny, with remarks on Panthera shawi (Broom, 1948), and a revision of Puma incurva (Ewer, 1956), the Early Pleistocene Swartkrans "leopard" (Carnivora, Felidae)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 103 (2): 465–487. Bibcode:2023PdPe..103..465H. doi:10.1007/s12549-022-00542-2.

- ^ Jiangzuo, Qigao; Wang, Yuan; Ge, Junyi; Liu, Sizhao; Song, Yayun; Jin, Changzhu; Jiang, Hao; Liu, Jinyi (2023). "Discovery of jaguar from northeastern China middle Pleistocene reveals an intercontinental dispersal event". Historical Biology. 35 (3): 293–302. Bibcode:2023HBio...35..293J. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2034808. S2CID 246693903.

- ^ Jiangzuo, Q.; Madurell-Malapeira, J.; Li, X.; Estraviz-López, D.; Mateus, O.; Testu, A.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Deng, T. (2025). "Insights on the evolution and adaptation toward high-altitude and cold environments in the snow leopard lineage". Science Advances. 11 (3): eadp5243. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adp5243. PMC 11734717. PMID 39813339.

- ^ Sabol, M. (2011). "Masters of the lost world: a hypothetical look at the temporal and spatial distribution of lion-like felids". Quaternaire. 4: 229–236.

- ^ Stuart, A. J., Lister, A .M. (2011). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17): 2329–2340. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2329S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sala, B. (1990). "Panthera leo fossilis (v. Reichenau, 1906) (Felidae) de Iserna la Pineta (Pléistocene moyen inférieur d'Italie)". Géobios. 23 (2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(06)80051-3.

- ^ Marciszak, A.; Stefaniak, K. (2010). "Two forms of cave lion: Middle Pleistocene Panthera spelaea fossilis Reichenau, 1906 and Upper Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 from the Bísnik Cave, Poland". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 258 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0117. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Marciszak, A.; Schouwenburg, C.; Darga, R. (2014). "Decreasing size process in the cave (Pleistocene) lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) evolution – A review". Quaternary International. Fossil remains in karst and their role in reconstructing Quaternary paleoclimate and paleoenvironments. 339–340: 245–257. Bibcode:2014QuInt.339..245M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.008.

- ^ Sotnikova, M. V.; Foronova, I. V. (2014). "First Asian record of Panthera (Leo) fossilis (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae) in the Early Pleistocene of Western Siberia, Russia". Integrative Zoology. 9 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12082. PMID 24382145.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), resolve its position within the Panthera cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24. hdl:10576/22920.

- ^ Stuart, Anthony J.; Lister, Adrian M. (August 2011). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17–18): 2329–2340. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2329S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023. Archived from the original on 24 April 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Pei, W. C. (1934). "On the Carnivora from Locality 1 of Choukoutien". Palaeontologica Sinica Series C, Fascicle 1: 1−166.

- ^ Jiangzuo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ge, J.; Liu, S.; Song, Y.; Jin, C.; Jiang, H.; Liu, J. (2023). "Discovery of jaguar from northeastern China middle Pleistocene reveals an intercontinental dispersal event". Historical Biology. 35 (3): 293–302. Bibcode:2023HBio...35..293J. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2034808. S2CID 246693903.

- ^ Manamendra-Arachchi, K., Pethiyagoda, R., Dissanayake, R., Meegaskumbura, M. (2005). "A second extinct big cat from the late Quaternary of Sri Lanka" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology (Supplement 12): 423–434. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Payan, E.; Murillo, A. & Alvarez, D. (2006). "DNA microsatellite characterization of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Colombia". Genes & Genetic Systems. 81 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1266/ggs.81.115. PMID 16755135. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Moreno, A.; Lima-Ribeiro, M. (2015). "Ecological niche models, fossil record and the multi-temporal calibration for Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758) (Mammalia: Felidae)" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Biological Sciences. 2 (4): 309–319. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Roth, S. (1899). "Descripción de los restos encontrados en la caverna de Última Esperanza". Revista del Museo la Plata. 9: 381–388.

- ^ Paijmans, J. L. A.; Barlow, A.; Förster, D. W.; Henneberger, K.; Meyer, M.; Nickel, B.; Nagel, D.; Havmøller, R. W.; Baryshnikov, G. F.; Joger, U.; Rosendahl, W.; Hofreiter, M. (2018). "Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18 (1): 156. Bibcode:2018BMCEE..18..156P. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0. PMC 6198532. PMID 30348080.

- ^ a b c Hasegawa, Y.; Tomida, Y.; Kohno, N.; Ono, K.; Nokariya, H.; Uyeno, T. (1988). "Quaternary vertebrates from Shiriya area, Shimokita Pininsula, northeastern Japan". Memoirs of the National Science Museum. 21: 17–36.

- ^ Turner, A. (1984). "Panthera crassidens Broom, 1948. The cat that never was?" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 80 (5): 227–233.

- ^ Bakr, Abu (1986). "105: On a collection of Siwalik Carnivora". Proceedings of Fourth Pakistan Congress of Zoology held under the auspices of the Zoological Society of Pakistan, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, December 20-22, 1983. Biological Society of Pakistan. p. 51. OCLC 62447645.

- ^ Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". In Macdonald, D. W. & Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Piras, P.; Silvestro, D.; Carotenuto, F.; Castiglione, S.; Kotsakis, A.; Maiorino, L.; Melchionna, M.; Mondanaro, A.; Sansalone, G.; Serio, C.; Vero, V.A.; Raia, P. (2018). "Evolution of the sabertooth mandible: A deadly ecomorphological specialization". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 496: 166−174. Bibcode:2018PPP...496..166P. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.01.034. hdl:2158/1268434.

Further reading

[edit]- Turner, A.; Antón, M. (1997). The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Panthera at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Panthera at Wikimedia Commons- The Ghostly Origins of the Big Cats (video). PBS Eons. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021 – via YouTube.

KSF

KSF