Pasiphaë

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

| Pasiphaë | |

|---|---|

Sorceress goddess | |

Pasiphaë sits on a throne, a Roman mosaic from Zeugma Mosaic Museum | |

| Abode | Crete |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Helios and Perse of Crete |

| Siblings | Circe, Aeetes, Aloeus, Perses, Phaethon, the Heliades, the Heliadae and others |

| Consort | Minos, Cretan Bull |

| Children | Acacallis, Ariadne, Androgeus, Glaucus, Deucalion, Phaedra, Xenodice, Catreus and the Minotaur. |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

In Greek mythology, Pasiphaë (/pəˈsɪfiiː/;[1] Ancient Greek: Πασιφάη, romanized: Pāsipháē, lit. 'wide-shining', derived from πᾶσι (dative plural) "for all" and φάος/φῶς phaos/phos "light")[2] was a queen of Crete. The daughter of Helios and the Oceanid nymph Perse, Pasiphaë is notable as the mother of the Minotaur. Her husband, Minos, failed to sacrifice the Cretan Bull to Poseidon as he had promised. Poseidon then cursed Pasiphaë to fall in love with the bull. Athenian inventor Daedalus built a hollow cow for her to hide in so she could mate with the bull, which resulted in her conceiving the Minotaur.

Family

[edit]Parentage

[edit]Pasiphaë was the daughter of god of the Sun, Helios,[3][4][5][6] and the Oceanid nymph[7] Perse.[8][9][10] She was thus the sister of Aeëtes, Circe and Perses of Colchis. In some accounts, Pasiphaë's mother was identified as the island-nymph Crete herself.[11][12] Like her doublet[clarification needed] Europa, the consort of Zeus, her origins were in the East, in her case at the earliest-known Kartvelian-speaking polity of Colchis (Egrisi (Georgian: ეგრისი), now in western Georgia[13][14][15][16]).

Marriage and children

[edit]Pasiphaë was given in marriage to King Minos of Crete. With Minos, she was the mother of Acacallis, Ariadne, Androgeus, Glaucus, Deucalion,[17] Phaedra, Xenodice, and Catreus.

After having sex with the Cretan Bull, she gave birth to the "star-like" Asterion, who became known as the Minotaur.

Mythology

[edit]

Birth of the Minotaur

[edit]Minos was required to sacrifice "the fairest bull born in its herd" to Poseidon each year. One year, an extremely beautiful snow-white bull was born: the Cretan Bull. Minos refused to sacrifice the animal, and sacrificed another, inferior bull instead. As punishment, Poseidon cursed Pasiphaë to experience lust for the Cretan bull.

Ultimately, Pasiphaë went to Daedalus and asked him to help her mate with the bull. Daedalus then created a hollow wooden cow covered with real cow-skin, so realistic that it fooled the Cretan Bull. Pasiphaë climbed into the structure, allowing the bull to mate with her. Pasiphaë fell pregnant and gave birth to a half-human half-bull creature that fed solely on human flesh. The child was named Asterius, after the previous king, but was commonly called the Minotaur ("the bull of Minos").[18][19][20]

The myth of Pasiphaë's coupling with the bull and the subsequent birth of the Minotaur was the subject of Euripides's lost play the Cretans, of which few fragments survive. Sections include a chorus of priests presenting themselves and addressing Minos, someone (perhaps a wetnurse) informing Minos of the newborn infant's nature (informing Minos and the audience, among others, that Pasiphaë breastfeeds the Minotaur like an infant), and a dialogue between Pasiphaë and Minos where they argue over which between them is responsible.[21] Pasiphaë's speech defending herself is preserved, an answer to Minos' accusations (not preserved) in which she excuses herself on account of acting under the constraint of divine power, and insists that the one to blame is actually Minos, who angered the sea-god.[22]

PASIPHAË:

If I had sold the gifts of Kypris,

given my body in secret to some man,

you would have every right to condemn me

as a whore. But this was no act of the will;

I am suffering from some madness brought on

by a god.

It’s not plausible!

What could I have seen in a bull

to assault my heart with this shameful passion?

Did he look too handsome in his robe?

Did a sea of fire smoulder in his eyes?

Was it the red tint of his hair, his dark beard?[23]

Mythological scholars and authors Ruck and Staples remarked that "the Bull was the old pre-Olympian Poseidon".[24]

Variations on the myth

[edit]Pseudo-Apollodorus mentions a slightly differing reason for why Poseidon cursed Pasiphaë; citing that Minos wanted to be king, and he called upon Poseidon to send him a bull in order to prove to the kingdom that he had received sovereignty from the gods. Upon calling on Poseidon, Minos failed to sacrifice the bull, as Poseidon wished, causing the god to grow angry with him.

According to sixth century BC author Bacchylides, the curse was instead sent by Aphrodite[25] and Hyginus says this was because Pasiphaë had neglected Aphrodite's worship for years.[26] In yet another version, Aphrodite cursed Pasiphaë (as well as several of her sisters) with unnatural desires as a revenge against her father Helios,[27] for he had revealed to Aphrodite's husband Hephaestus her secret affair with Ares, the god of war, earning Aphrodite's eternal hatred for himself and his whole race.[28][29]

In some more obscure traditions, it was not Poseidon's bull but Minos' father Zeus disguised as one who made love to Pasiphaë and sired the Minotaur.[30] An ancient Greek lexicon mentions a tradition where Zeus and Pasiphaë are the parents of the Egyptian god Amun, who was identified with Zeus.[31]

Pasiphaë's curse

[edit]In other aspects, Pasiphaë, like her niece Medea, was a mistress of magical herbal arts in the Greek imagination. The author of Bibliotheke records the fidelity charm she placed upon Minos that caused him to ejaculate serpents, scorpions, and centipedes whenever he laid with another woman, killing them. However, Procris, after consuming a protective circean herb, lay with Minos with impunity.[32]

In another version, this unexplained disease that tormented Minos killed all his concubines and prevented him and Pasiphaë from having any children (the scorpions and serpents did not otherwise harm Pasiphaë, as she was an immortal child of the Sun). Procris then inserted a goat's bladder into a woman, told Minos to ejaculate the scorpions in there, and then sent him to Pasiphaë. The couple was thus able to conceive eight children.[5] Records indicate, this became the first modern documentation of a sheath or condom, though working to promote fertility.[33]

Daedalus and Icarus

[edit]In one version of the story, Pasiphaë supplied Daedalus and his son Icarus with a ship in order to escape Minos and Crete.[34] In another, she helped him hide until he fashioned wings made of wax and bird feathers.[35]

Variations about Pasiphaë's death

[edit]While Pasiphaë is an immortal goddess in some texts, other authors treated her as a mortal woman, like Euripides who in his play Cretans has Minos sentence her to death (her eventual fate is unclear, as no relevant fragment survives). In Virgil's Aeneid, Aeneas sees her when he visits the Underworld, describing Pasiphae residing in the Mournful Fields, a place inhabited by sinful lovers.[36]

Personae of Pasiphaë

[edit]In the general understanding of the Minoan myth,[37] Pasiphaë and Daedalus'[38] construction of the wooden cow allowed her to satisfy her desire[39] for the Cretan Bull. Through this interpretation she was reduced from a near-divine figure (daughter of the Sun) to a stereotype of grotesque bestiality and the shocking excesses of lust and deceit.[40]

Pasiphaë appeared in Virgil's Eclogue VI (45–60), in Silenus' list of suitable mythological subjects, on which Virgil lingers in such detail that he gives the sixteen-line episode the weight of a brief inset myth.[41]

In Ovid's Ars Amatoria, Pasiphaë is framed in zoophilic terms:

Pasiphae fieri gaudebat adultera tauri—"Pasiphaë took pleasure in becoming an adulteress with a bull."[42]

Pasiphaë is often included on lists among mythical women ruled by lust; other women include Phaedra, Byblis, Myrrha, Scylla and Semiramis. Scholars see her as a personified sin of bestiality.[43]

Ars Amatoria shows Pasiphaë's jealousy of the cows; she's primping in front of a mirror while she laments that she is not a cow and killing her rivals.[43]

Cult of Pasiphaë

[edit]

On divination

[edit]In mainland Greece, Pasiphaë was worshipped as an oracular goddess at Thalamae, one of the original koine of Sparta. The geographer Pausanias describes the shrine as small, situated near a clear stream, and flanked by bronze statues of Helios and Pasiphaë. His account also equates Pasiphaë with Ino and the lunar goddess Selene.

Cicero writes in De Divinatione 1.96 that the Spartan ephors would sleep at the shrine of Pasiphaë, seeking prophetic dreams to aid them in governance. According to Plutarch,[44] Spartan society twice underwent major upheavals sparked by ephors' dreams at the shrine during the Hellenistic era. In one case, an ephor dreamed that some of his colleagues' chairs were removed from the agora, and that a voice called out "this is better for Sparta"; inspired by this, King Cleomenes acted to consolidate royal power. Again during the reign of King Agis, several ephors brought the people into revolt with oracles from Pasiphaë's shrine promising remission of debts and redistribution of land.

Celestial deity

[edit]In Description of Greece, Pausanias equates Pasiphaë with Selene, implying that the figure was worshipped as a lunar deity.[45] However, further studies on Minoan religion indicate that the sun was a female figure, suggesting instead that Pasiphaë was originally a solar goddess, an interpretation consistent with her depiction as Helios' daughter.[46] Poseidon's bull may in turn be vestigial of the lunar bull prevalent in Ancient Mesopotamian religion.[47]

Nowadays, Pasiphaë and her son, the Minotaur, are associated with the astrological sign of Taurus.

Other representations

[edit]

In art

[edit]The myth of Pasiphaë and the Cretan Bull became widely depicted in art throughout history.[citation needed] Pasiphaë was most often depicted with a bull near her, signifying the connection to the myth.[citation needed]

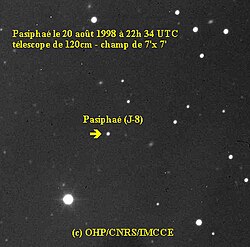

Scientific representation

[edit]One of Jupiter's 79 moons, discovered in 1908, is named after Pasiphaë, the woman of the myth of the Minotaur.

Literary representation

[edit]Pasiphaé is mentioned in Canto 12 of Dante Alighieri's Inferno. When Dante encounters the Minotaur, he describes the unnatural and deceptive manner of the beast's conception.

Fiona Benson's third collection of poetry, Ephemeron, contains a long section entitled Translations from the Pasiphaë in which she retells the Minotaur myth from the point of view of the bull-child's mother.

In popular culture

[edit]

- Pasiphaë is a major antagonist in Rick Riordan's 2013 fantasy novel The House of Hades. In this novel, she is portrayed as an immortal sorceress and former wife of the late King Minos. Having grown bitter towards the gods after the events of the Minoan myth, Pasiphaë allies with the goddess Gaea and her giant army to overthrow the Olympian gods. She is confronted and defeated by Hazel Levesque, a demigod daughter of Pluto, who had been trained in sorcery by the goddess Hecate. In this novel, it is revealed that the Labyrinth is tied to her life force as much as Daedalus's, thereby rendering the infamous inventor's sacrifice in the previous series useless.[48]

- Pasiphaë appears in Madeline Miller's 2018 novel Circe, the sister of the book's protagonist Circe, the daughter of Helios and Perse. A witch just like her, she and Circe have an antagonistic and sour relationship; after Pasiphaë has intercourse with the Cretan Bull, she calls in Circe to assist her in the Minotaur's birth though the two sisters hardly reconcile their differences. It's also heavily implied she entered an incestuous affair with her brother Perses, here presented as her twin.[49]

Genealogy

[edit]| Pasiphaë's family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Polyphonte, another woman in Greek mythology cursed to fall in love with an animal (a bear)

- History of zoophilia

- Solar deity

- Lunar deity

- Brazen Bull

Notes

[edit]- ^ Wells, John C. (2009). "Pasiphae, Pasiphaë". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. London: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ An attribute of the Moon, as Pausanias remarked in passing (i.43.96): compare Euryphaessa; if Pasipháē is an ancient conventional Minoan epithet translated into Greek, it would be a "loan translation", or calque.

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.999

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 9.735

- ^ a b Antoninus Liberalis, 41

- ^ Seneca, Phaedra 112

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 355

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.9.1

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae Preface

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 48.4

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.60.4

- ^ Tzetzes, Chiliades 4.361

- ^ David Marshall Lang. The Georgians. p. 59. Frederick A. Praeger. New York (1966).

- ^ Antiquity 1994. p. 359. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia: Значение слова "Колхи" в Большой Советской Энциклопедии

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History, John Anthony Crook, Elizabeth Rawson, p. 255

- ^ David Marshall Lang. The Georgians. p. 75, 76-88. Frederick A. Praeger. New York (1966).

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 14

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.1.4

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.77.1

- ^ Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 1.16.1

- ^ Johan Tralau, Cannibalism, Vegetarianism, and the Community of Sacrifice: Rediscovering Euripides' Cretans and the Beginnings of Political Philosophy, the University of Chicago Press Journals [1].

- ^ Sansone, David. “Euripides, Cretans Frag. 472e.16—26 Kannicht.” Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik, vol. 184, Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 2013, pp. 58–65.

- ^ Euripides, Cretans Fr. 472e K, translation by P. T. Rourke via Diotíma.

- ^ Ruck and Staples 1994:213.

- ^ Bacchylides "frag 26".

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 40

- ^ Libanius, Progymnasmata 2.21

- ^ Seneca, Phaedra 124

- ^ Scholia on Euripides' Hippolytus 47.

- ^ Porphyry, On Abstinence from Animal Food 3.16

- ^ Lexicon of Greek Language s.v. Ἄμμων

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.15.1

- ^ Peel, John; Finch, B. E.; Green, Hugh (March 1965). "Contraception through the Ages". Population Studies. 18 (3): 330. doi:10.2307/2173294. JSTOR 2173294.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.77.5

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.77.7

- ^ Virgil, Aeneid 6.447

- ^ Specific astrological or calendrical interpretations of the mystic mating of the "wide-shining" daughter of the Sun with a mythological bull, transformed into an unnatural curse in Hellene myth, are prone to variability and debate.

- ^ Daedalus was of the line of the chthonic king at Athens Erechtheus.

- ^ Greek myth characteristically emphasizes the accursed unnaturalness of a mystical marriage conceived literally as merely carnal: a fragment of Bacchylides alludes to "her unspeakable sickness" and Hyginus (in Fabulae 40) to "an unnatural love for a bull".

- ^ This was the commonplace of brief notices of Pasiphaë among Latin poets, too, Rebecca Armstrong notes, in Cretan Women: Pasiphae, Ariadne, and Phaedra in Latin Poetry (Oxford University Press) 2006:169. Ruck and Staples (1994:9) argue that "the suspension of linear chronology" is a common feature in Greek myths.

- ^ Armstrong 2006:171.

- ^ Ovid, Ars Amatoria 1.9.33

- ^ a b Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate (1996). "The Scandal of Pasiphae: Narration and Interpretation in the "Ovide moralisé"". Modern Philology. 93 (3): 307–326. doi:10.1086/392321. ISSN 0026-8232. JSTOR 438324. S2CID 162197853.

- ^ Plutarch, Parallel Lives Agis and Cleomenes.

- ^ Pausanias, 3.26.1

- ^ Goodison, L. “From Tholos Tomb to Throne Room: Perceptions of the Sun in Minoan Ritual”. In: R. LAFFINEUR and R. HÄGG (eds.). Potnia: Deities and Religion in the Aegean Bronze Age. 2001. pp. 77-88.

- ^ "Bull (Mythology)". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ^ Riordan, Rick (2013). The House of Hades. New York City: Disney-Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4231-4672-8.

- ^ Miller, Madeline (2018). Circe. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-55634-7.

References

[edit]Ancient

[edit]- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Bacchylides in Bacchylides, Corinna. Greek Lyric, Volume IV: Bacchylides, Corinna, and Others. Edited and translated by David A. Campbell. Loeb Classical Library 461. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Euripides, Cretans fragments in Fragments: Aegeus-Meleager. Edited and translated by Christopher Collard, Martin Cropp. Loeb Classical Library 504. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica translated by Robert Cooper Seaton (1853–1915), R. C. Loeb Classical Library Volume 001. London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1912. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica. Vol 1-2. Immanel Bekker. Ludwig Dindorf. Friedrich Vogel. in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. Leipzig. 1888–1890. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Antoninus Liberalis, The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis translated by Francis Celoria (Routledge 1992). Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Philostratus the Elder, Imagines, translated by A. Fairbanks, Loeb Classical Library No, 256. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1931. ISBN 978-0674992825. Internet Archive

- Plutarch, and Bernadotte Perrin. Plutarch's Lives. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Vergil, Aeneid. Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses. Translated by A. D. Melville; introduction and notes by E. J. Kenney. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-953737-2.

- Ovid, The Amores, Ars Amatoria, Remedia Amoris and Medicamina Faciei Femineae of Publius Ovidius Naso, translated out of the Latin by J. Lewis May, illustrated by Jean De Bosschere, privately printed for Rarity Press, New York, 1930. Online version available at sacred-texts.com.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Nature of the Gods from the Treatises of M.T. Cicero translated by Charles Duke Yonge (1812–1891), Bohn edition of 1878. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Seneca, Tragedies, translated by Miller, Frank Justus. Loeb Classical Library Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1917.

- Tzetzes, John, Book of Histories, Book II-IV translated by Gary Berkowitz from the original Greek of T. Kiessling's edition of 1826. Online version available at Theoi.com

Modern

[edit]- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks, 1951.

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths, (1955) 1960.

- Ruck, Carl A.P., and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth 1994.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Past'piiae"

External links

[edit] Media related to Pasiphae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pasiphae at Wikimedia Commons- PASIPHAE from the Theoi Project

- PASIPHAE from greekmythology.com

KSF

KSF