Petro Poroshenko

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 53 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 53 min

Petro Poroshenko | |

|---|---|

Петро Порошенко | |

Poroshenko in 2023 | |

| 5th President of Ukraine | |

| In office 7 June 2014 – 20 May 2019 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Oleksandr Turchynov (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Volodymyr Zelenskyy |

| Minister of Trade and Economic Development | |

| In office 13 March 2012 – 4 December 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Mykola Azarov |

| Preceded by | Andriy Klyuyev |

| Succeeded by | Ihor Prasolov |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 9 October 2009 – 11 March 2010 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Volodymyr Khandohiy |

| Succeeded by | Kostyantyn Gryshchenko |

| Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council | |

| In office 8 February 2005 – 8 September 2005 | |

| President | Viktor Yushchenko |

| Preceded by | Volodymyr Radchenko |

| Succeeded by | Anatoliy Kinakh |

| People's Deputy of Ukraine | |

| Assumed office 29 August 2019 | |

| Constituency | European Solidarity, No. 1 |

| In office 12 December 2012 – 3 June 2014 | |

| Succeeded by | Oleksii Poroshenko |

| Constituency | Vinnytsia Oblast, No. 12[1] |

| In office 12 May 1998 – 15 June 2007 | |

| Constituency |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 September 1965 Bolhrad, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union (now Bolhrad, Odesa Oblast, Ukraine) |

| Political party | European Solidarity (2019–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4, including Oleksii |

| Residence(s) | Kozyn, Kyiv Oblast |

| Alma mater | Taras Shevchenko National University |

| Occupation | Businessman; Politician |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | |

Petro Oleksiiovych Poroshenko[a][b] (born 26 September 1965) is a Ukrainian oligarch[6][7] and politician who served as the fifth president of Ukraine from 2014 to 2019.

Poroshenko served as the minister of foreign affairs from 2009 to 2010, and as the minister of trade and economic development in 2012. From 2007 until 2012, he headed the Council of Ukraine's National Bank. He was elected president in 2014.

During his presidency, Poroshenko led the country through the first phase of the war in Donbas, pushing the Russian separatist forces into the Donbas Region. He began the process of integration with the European Union by signing the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement. Poroshenko's domestic policy promoted the Ukrainian language, nationalism, inclusive capitalism, decommunization, and administrative decentralization. In 2018, Poroshenko helped create the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine, separating Ukrainian churches from the Moscow Patriarchate. His presidency was distilled into a three-word slogan, employed by both supporters and opponents: armiia, mova, vira (English: military, language, faith).[8] As a candidate for a second term in 2019, Poroshenko was defeated by Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Poroshenko is a people's deputy of the Verkhovna Rada and leader of the European Solidarity party. Outside government, Poroshenko has been a prominent Ukrainian oligarch with a lucrative career in acquiring and building assets. His most recognized brands are Roshen, a large-scale confectionery company which has earned him the nickname of "Chocolate King", and his TV news channel 5 Kanal, which he was forced to sell to comply with anti-oligarch legislation in November 2021.[9] He is considered an oligarch due to the scale of his business holdings in manufacturing, agriculture and finance, his political influence from several stints in government prior to his presidency, and his ownership of an influential mass-media outlet.[10]

Early life and education

[edit]Petro Poroshenko was born on 26 September 1965, into an ethnic Ukrainian family in Bolhrad, a primarily Bulgarian town in Ukraine's southwestern Odesa Oblast. Poroshenko's father Oleksiy Poroshenko (1936–2020),[11] was an engineer and later a government official who managed multiple factories in the Ukrainian SSR. Little is known about his mother, Yevhenia Serhiyivna Hryhorchuk (1937–2004), but a Ukrainian newspaper said she was an accountant, who taught at a vocational and technical school of accounting.[12] He also spent his childhood and youth in Tighina (Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, now known as Bender and under de facto control of the unrecognized breakaway state Transnistria),[13][14] where his father Oleksii was heading a machine building plant[13] and where he learned Romanian.[15]

In his youth, Poroshenko practiced judo and sambo, and was a Candidate for Master of Sport of the USSR.[16] Despite good grades, he was not awarded the normal gold medal at graduation, and on his report card he was given a "C" for his behavior.[17] After getting into a fight with four Soviet Army cadets at the military commissariat, he was sent to army service[when?] in the distant Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.[17]

In 1989, Poroshenko graduated, having begun studying in 1982, with a degree in economics from the international relations and law department (subsequently the Institute of International Relations) at the Kyiv University.[18] At this university he was friends with Mikheil Saakashvili who he would appoint as Governor of the Odesa Oblast (region) in May 2015 and who is a former President of Georgia.[19]

In 1984, Poroshenko married a medical student, Maryna Perevedentseva (born 1962).[16] Their first son, Oleksiy, was born in 1985 (his three other children were born in 2000 and 2001).[16]

From 1989 to 1992, Poroshenko was an assistant at the university's international economic relations department.[16] While still a student, he founded a legal advisory firm mediating the negotiation of contracts in foreign trade, and then he undertook the negotiations himself, starting to supply cocoa beans to the Soviet chocolate industry in 1991.[16] At the same time, he was deputy director of the 'Republic' Union of Small Businesses and Entrepreneurs, and the CEO "Exchange House Ukraine".[16]

Poroshenko's brother, Mykhailo, older by eight years, died in a 1997 car crash under mysterious circumstances.[20]

Business career

[edit]In 1993, Poroshenko, together with his father Oleksii and colleagues from the Road Traffic Institute in Kyiv, created the UkrPromInvest Ukrainian Industry and Investment Company, which specialized in the confectionery and automotive industries (as well as in other agricultural processing later on).[16] Poroshenko was director-general of the company from its founding until 1998, when in connection with his entry into parliament he handed the title over to his father, while retaining the title of honorary president.[16]

Between 1996 and 1998, UkrPromInvest acquired control over several state-owned confectionery enterprises which were combined into the Roshen group in 1996, creating the largest confectionery manufacturing operation in Ukraine.[16] His business success in this industry earned him the nickname "Chocolate King".[21] Poroshenko's business empire also includes several car and bus factories, Kuznia na Rybalskomu shipyard, the 5 Kanal television channel,[22] as well as other businesses in Ukraine.

Although not the most prominent in the list of his business holdings, the assets that drew much recent media attention, and often controversy, are the confectionery factory in Lipetsk, Russia, that became controversial due to the Russo-Ukrainian war, the Sevastopol Marine Plant (Sevmorzavod) that has been confiscated after the 2014 Russian forcible annexation of Crimea and the media outlet 5 kanal, particularly because of Poroshenko's repeated refusal to sell an influential media asset following his accession to presidency.

According to Poroshenko (and Rothschild Wealth Management & Trust) since becoming President of Ukraine he has relinquished the management of his businesses, ultimately (in January 2016) to a blind trust.[13][23]

Billionaires lists rankings

[edit]In March 2012, Forbes placed him on the Forbes list of billionaires at 1,153rd place, with US$1 billion.[24] As of May 2015, Poroshenko's net worth was about US$720 million (Bloomberg estimate), losing 25 percent of his wealth because of Russia's ban of Roshen products and the state of the Ukrainian economy.[25]

According to the annual ranking of the richest people in Ukraine,[26] published in October 2015 by the Ukrainian journal Novoye Vremya and conducted jointly with Dragon Capital, a leading investment company in Ukraine, president Poroshenko was found to be the only one from the top ten list whose asset value grew since the previous year's ranking. The estimate of his assets was set at US$979 million, a 20% growth, and his ranking increased from 9th to 6th wealthiest person in Ukraine. The article observed that Poroshenko remained one of the only two European leaders who owned a business empire of such scale, with Silvio Berlusconi of Italy being the other.

A total of €450 million is kept in an Amsterdam-based company registered in Cyprus, as a result of which his effective tax rate is 5% rather than the statutory tax rate of 18% in Ukraine. The company is probably to be worth much more, as the annual accounts published by the Dutch Chamber of Commerce only contain the book value of the shares, which is very likely to be lower than the market value.[27] After his election, Poroshenko lost the billionaire status as his net worth dropped by 40% to reach $705 million.[28]

Associated businesses

[edit]A number of businesses were once part of the Ukrprominvest [uk] which Poroshenko headed in 1993–1998. The investment group was dissolved in April 2012.[29] Poroshenko has stated that upon beginning his political activity he passed on his holdings to a trust fund.[16]

- Bogdan group (Poroshenko sold his share in connection with the collapse of its production after the financial crisis of 2007–2008 in 2009),[16] centered in Cherkasy

- Roshen group

- 5 Kanal and Priamyi television channels (he denies property relations with Priamyi[30])

- Kuznia na Rybalskomu shipyard[16] in Kyiv

- International Invest Bank,[31] owned through a trust and along with Ihor Kononenko

- Ukrprominvest-Agro, an agrarian holding

- Zoria Podillia, an agrarian company near Haisyn, specializing in sugar production from sugar beets

- Podillia

- MAS-Agro

- Ahrofirma "Dniproahrolan"

- Ahrofirma "Ivankivtsi"

- Sevastopol Shipyard (lost in 2015 due to a corporate raid by the Russian occupational authorities in Crimea)

Early political career

[edit]Poroshenko first won a seat in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian Parliament) in 1998 for the 12th single-mandate constituency. He was initially a member of the United Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (SDPU), the party led by Viktor Medvedchuk and loyal to president Leonid Kuchma at the time.[16] Poroshenko left SDPU(o) in 2000 to create an independent left-of-center faction and then a party, naming it Party of Ukraine's Solidarity (PSU).[16][32] In 2001 Poroshenko was instrumental in creating the Party of Regions, also loyal to Kuchma; the Party of Ukraine's Solidarity having merged into the Party of Regions, Poroshenko launched a new party with a similar name, the party "Solidarity".[33]

Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council

[edit]

In December 2001, Poroshenko broke ranks with Kuchma supporters to become campaign chief of Viktor Yushchenko's Our Ukraine Bloc opposition faction. After parliamentary elections in March 2002 in which Our Ukraine won the biggest share of the popular vote and Poroshenko won a seat in parliament,[16][34] Poroshenko served as head of the parliamentary budget committee, where he was accused of "misplacing ₴47 million" (US$8.9 million).[35] As a consequence of Poroshenko's Our Ukraine Bloc membership tax inspectors launched an attack on his business.[16] Despite great difficulties, UkrPromInvest managed to survive until Yushchenko became President of Ukraine in 2005.[16]

Poroshenko was considered a close confidant of Yushchenko, who is the godfather of Poroshenko's daughters.[36] Poroshenko was probably the wealthiest oligarch among Yushchenko supporters, and was often named as one of the main financial backers of Our Ukraine and the Orange Revolution.[37] After Yushchenko won the presidential elections in 2004, Poroshenko was appointed Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council.[16][18]

In September 2005, highly publicized mutual allegations of corruption erupted between Poroshenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko involving the privatizations of state-owned firms.[38] Poroshenko, for example, was accused of defending the interests of Viktor Pinchuk, who had acquired state firm Nikopol Ferroalloy for $80 million, independently valued at $1 billion.[39]

In response to the allegations, Yushchenko dismissed his entire cabinet of ministers, including Poroshenko and Tymoshenko.[40] State prosecutors dismissed an abuse of power investigation against Poroshenko the following month,[41] immediately after Yushchenko dismissed Sviatoslav Piskun, General Prosecutor of Ukraine. Piskun claimed that he was sacked because he refused to institute criminal proceedings against Tymoshenko and refused to drop proceedings against Poroshenko.[42]

In the March 2006 parliamentary election, Poroshenko was re-elected to the Ukrainian parliament with the support of Our Ukraine electoral bloc.[16] He chaired the parliamentary Committee on Finance and Banking. Allegedly, since Poroshenko claimed the post of Chairman of the Ukrainian Parliament for himself, the Socialist Party of Ukraine chose to be part of the Alliance of National Unity because it was promised that their party leader, Oleksandr Moroz, would be elected chairman if the coalition were formed.[40] This left Poroshenko's Our Ukraine and their ally Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc out of the Government.

Poroshenko did not run in the September 2007 parliamentary election.[16] Poroshenko started heading the Council of Ukraine's National Bank in February 2007.[40][43] Between 1999 and 2012 he was a board member of the National Bank of Ukraine.[16]

Foreign Minister and Minister of Trade

[edit]

Ukrainian President Yushchenko nominated Poroshenko for Foreign Minister on 7 October 2009.[43][44] Poroshenko was appointed by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament) on 9 October 2009.[45][46] On 12 October 2009, President Yushchenko re-appointed Poroshenko to the National Security and Defense Council.[47]

Poroshenko supported Ukrainian NATO-membership, and said NATO membership should not be a goal in itself.[48] Although Poroshenko was dismissed as foreign minister on 11 March 2010, President Viktor Yanukovych expressed hope for further cooperation with him.[22]

In late February 2012, Poroshenko was named as the new Minister of Trade and Economic Development in the Azarov Government;[49][50][51] on 9 March 2012, President Yanukovych stated he wanted Poroshenko to work in the government in the post of economic development and trade minister.[52] On 23 March 2012, Poroshenko was appointed economic development and trade minister of Ukraine by Yanukovych.[53] The same month he stepped down as head of the Council of Ukraine's National Bank.[54]

Poroshenko claims that he became Minister of Trade and Economic Development to help bring Ukraine closer to the EU and get Yulia Tymoshenko released from prison.[17] After he took the post, tax inspectors launched an attack on his business.[17]

Return to parliament

[edit]Poroshenko returned to the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) after the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election after winning (with more than 70%) as an independent candidate in single-member district number 12 (first-past-the-post wins a parliamentary seat) located in Vinnytsia Oblast.[55][56][57] He did not enter any faction in parliament[58] and became member of the committee on European Integration.[17] Poroshenko's father Oleksii did intend to take part in the elections too in single-member district number 16 (also located in Vinnytsia Oblast), but withdrew his candidacy for health reasons.[59][60] In mid-February 2013, Poroshenko hinted he would run for Mayor of Kyiv in the 2013 Kyiv mayoral election.[61]

In 2013, the registration certificate of Solidarity was cancelled because it had not participated in any election for more than 10 years.[33] Poroshenko then launched and became leader of the National Alliance of freedom and Ukrainian patriotism "OFFENSIVE" (NASTUP), which was renamed "All-Ukrainian Union Solidarity" (BOS).[33]

2014 Revolution of Dignity

[edit]

Poroshenko actively and financially supported the Euromaidan protests between November 2013 and February 2014,[16] leading to an upsurge in his popularity, although[16] he did not participate in negotiations between then President Yanukovych and the Euromaidan parliamentary opposition parties Batkivshchyna, Svoboda and UDAR.[16]

In an interview with Lally Weymouth, Poroshenko said: "From the beginning, I was one of the organizers of the Maidan. My television channel — Channel 5 — played a tremendously important role. ... At that time, Channel 5 started to broadcast, there were just 2,000 people on the Maidan. But during the night, people went by foot — seven, eight, nine, 10 kilometers — understanding this is a fight for Ukrainian freedom and democracy. In four hours, almost 30,000 people were there."[62] The BBC reported, "Mr Poroshenko owns 5 Kanal TV, the most popular news channel in Ukraine, which showed clear pro-opposition sympathies during the months of political crisis in Kiev."[36]

Poroshenko refused to join the Yatseniuk Government (although he introduced his colleague Volodymyr Groysman, the mayor of Vinnytsia, into it), nor did he join any of the two newly created parliamentary factions Economic Development and Sovereign European Ukraine.[16]

On 24 April 2014, Poroshenko visited Luhansk, at the time not controlled by Ukrainian authorities.[13] Just like previously in Crimea he was met by a blockade of hundreds of pro-Russian locals at Luhansk Airport.[13] Poroshenko later claimed: "When I traveled to Luhansk Oblast, my car was fired at and there was an attempt to take our entire group hostage."[13]

2014 presidential campaign

[edit]

Following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the resulting removal of Viktor Yanukovych from the office of President of Ukraine, new presidential elections were scheduled to take place on 25 May 2014.[63] In pre-election polls from March 2014, Poroshenko garnered the most support of all the prospective candidates, with one poll conducted by SOCIS giving him a rating of over 40%.[64] On 29 March he stated that he would run for president; at the same time Vitali Klitschko left the presidential contest, choosing to support Poroshenko's bid.[65][66][67][68]

On 2 April, Poroshenko stated, "If I am elected, I will be honest and sell the Roshen Concern."[69] He also said in early April that the level of popular support for the idea of Ukraine's joining NATO was too small to put on the agenda "so as not to ruin the country".[70] He also vowed not to sell his 5 Kanal television channel.[71] On 14 April, Poroshenko publicly endorsed the campaign of Jarosław Gowin's party Poland Together of neighboring Poland in that year's elections to the European Parliament, thanking Gowin's party colleague Paweł Kowal for supporting Ukraine.[72]

Poroshenko's election slogan was: "Live in a new way – Poroshenko!".[17]

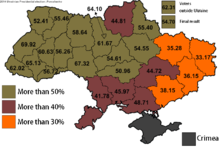

On 29 May, the Central Election Commission of Ukraine announced that Poroshenko had won the 25 May presidential election, with 54.7% of the votes.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

During his visit in Berlin, Poroshenko stated that Russian separatists in the Donbas "don't represent anybody. We have to restore law and order and sweep the terrorists off the street."[79] He described as "fake" the planned 11 May Donbas status referendums.[79]

Presidency (2014–2019)

[edit]When it became clear he had won the election on election day evening (on 25 May 2014) Poroshenko announced his "first presidential trip will be to Donbas", where armed pro-Russian rebels had declared the separatist republics Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic and control part of the region.[71][80] Poroshenko also vowed to continue the military operations by the Ukrainian government forces to end the armed insurgency claiming: "The anti-terrorist operation cannot and should not last two or three months. It should and will last hours."[81]

He compared the armed pro-Russian rebels to Somali pirates.[81] Poroshenko also called for negotiations with Russia in the presence of international intermediaries.[81] Russia responded by saying it did not need an intermediary in its bilateral relations with Ukraine.[81] As president-elect, Poroshenko promised to return Crimea,[81] which was annexed by Russia in March 2014.[80][82][c] He also vowed to hold new parliamentary elections in 2014.[84]

Inauguration

[edit]Poroshenko was inaugurated in the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) on 7 June 2014.[85] In his inaugural address he stressed that Ukraine would not give up Crimea and stressed the unity of Ukraine.[86] He promised an amnesty "for those who do not have blood on their hands" to the separatist and pro-Russia insurgents of the 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine and to the Ukrainian nationalist groups that oppose them, but added: "Talking to gangsters and killers is not our path."[86] He also called for early regional elections in Eastern Ukraine.[86]

Poroshenko stated that he would sign the economic part of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement and that this was the first step towards full Ukrainian EU Membership.[86] During the speech, he stated he saw "Ukrainian as the only state language" but also spoke of the "guarantees [of] the unhindered development of Russian and all the other languages".[86] Part of the speech was in Russian.[86]

The inauguration was attended by about 50 foreign delegations, including US Vice President Joe Biden, President of Poland Bronisław Komorowski, President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko, President of Lithuania Dalia Grybauskaitė, President of Switzerland and the OSCE Chairman-in-Office Didier Burkhalter, President of Germany Joachim Gauck, President of Georgia Giorgi Margvelashvili, Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Hungary Viktor Orbán, President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy, the OSCE Secretary General Lamberto Zannier, UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Jeffrey Feldman, China's Minister of Culture Cai Wu and Ambassador of Russia to Ukraine Mikhail Zurabov[87][88] Former Prime Minister of Ukraine Yulia Tymoshenko was also present.[86][87] After the inauguration ceremony Tymoshenko said about Poroshenko, "I think Ukraine has found a very powerful additional factor of stability."[89]

Domestic policy

[edit]Peace plan for Eastern Ukraine

[edit]At the time of his inauguration, armed pro-Russian rebels, after disputed referendums, had declared the independence of the separatist Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic and controlled a large part of Donbas, but were largely considered to be illegitimate by the international community.[71][80] After the inauguration, Poroshenko launched a "peace" plan envisioned to garner the recognition of the presidential elections in Ukraine by Russia, consisting of a cease-fire with the separatists (named "terrorists" by Poroshenko himself) and the establishment of a humanitarian corridor for civilians ("who are not involved in the conflict").[90] Poroshenko warned that he had a "Plan B" if the initial peace plan was rejected.[91]

Decentralization of power

[edit]

In mid-June Poroshenko started the process of amending Ukraine's constitution to achieve Ukraine's administrative decentralization.[92] According to Poroshenko (on 16 June 2014) this was "a key element of the peace plan".[92] In his draft constitutional amendments of June 2014 proposed changing the administrative divisions of Ukraine, which should include regions (replacing the current oblasts), districts and "hromadas" (united territorial communities).[93]

In these amendments he proposed that "Village, city, district and regional administrations will be able to determine the status of the Russian language and other national minority languages of Ukraine in accordance with the procedure established by the law and within the borders of their administrative and territorial units".[94] He proposed that Ukrainian remained the only state language of Ukraine.[94]

Poroshenko proposed to create the post of presidential representatives who would supervise the enforcement of the Ukrainian constitution and laws and the observation of human rights and freedoms in oblasts and raions/raions of cities.[95] In case of an "emergency situation or martial law regime" they will "guide and organize" in the territories they are stationed in.[95] Batkivshchyna, a key coalition partner in the Yatseniuk Government, came out against the plan.[96] [why?]

He repeatedly spoke out against federalization,[97][98] and did not seek to increase his presidential powers.[99]

The 1 July 2015 decentralization draft law gave local authorities the right to oversee how their tax revenues are spent.[100] The draft law did not give an autonomous status to Donbas, as demanded by the pro-Russian rebels there, but gave the region partial self-rule for three years.[100]

Dissolution of Parliament

[edit]On 25 August 2014, Poroshenko called a snap election to the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament), to be held 26 October 2014.[101][102] According to him this was necessary "to purify the Rada of the mainstay of [former president] Viktor Yanukovych". These deputies, Poroshenko said, "clearly do not represent the people who elected them".[103] Poroshenko said that these Rada deputies were responsible for "the [January 2014] Dictatorship laws that took the lives of the Heavenly hundred".[103] Poroshenko stated that many of the (then) current MPs were "direct sponsors and accomplices or at least sympathizers of militant-separatists".[103]

Poroshenko had pressed for the elections since his victory in the May 2014 presidential election.[104][105][106]

On 27 August 2014, the party congress of All-Ukrainian Party of Peace and Unity adopted a new name: "Petro Poroshenko Bloc" (BPP).[107][33][108] In 2015, the Petro Poroshenko Bloc was renamed in "Petro Poroshenko Bloc "Solidarity"".[109]

Nuclear weapons

[edit]On 13 December 2014, Poroshenko stated that he did not want Ukraine to become a nuclear power again.[110]

Decommunization and deoligarchization

[edit]

On 15 May 2015, Poroshenko signed a bill into law that started a six month period for the removal of communist monuments and the mandatory renaming of streets and other public places and settlements with a name related to Communism.[111] According to Poroshenko, "I did what I had to"; adding, "Ukraine as a state has done its job, then historians should work, while the government should take care of the future."[111]

Poroshenko believes that the communist repression and Holodomor of the Soviet Union are on par with the Nazi crimes of the 1940s.[112] The legislation (Poroshenko signed on 15 May 2015) also provides "public recognition to anyone who fought for Ukrainian independence in the 20th century",[113] including the controversial Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) combatants led by Roman Shukhevych and Stepan Bandera.[111]

Poroshenko said in an interview with Germany's Bild newspaper that, "If I am elected, I'll wipe the slate clean and will sell the Roshen concern. As president of Ukraine, I will and want to only focus on the well-being of the nation."[114]

On 23 March 2015, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko accepted the resignation of billionaire Ihor Kolomoisky as governor of Dnipro region over the control of oil companies.[115] "There will be no more oligarchs in Ukraine", Poroshenko said adding that "oligarchs must pay more [taxes] than the middle class and more than small business". The president underscored that "the program of de-oligarchization will be put into life". Poroshenko promised that he will fight against the Ukrainian oligarchs.[116]

In December 2018, President Poroshenko confirmed the status of veterans and combatants for independence of Ukraine for the armed units of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA).[117]

Language

[edit]In 2016, a new rule came into force requiring Ukraine's radio stations to play a quota of Ukrainian-language songs each day. The law also requires TV and radio broadcasters to ensure 60% of programs such as news and analysis are in Ukrainian.[118]

On 25 September 2017, a new law on education was signed by President Poroshenko (draft approved by Rada on 5 September 2017) which says that the Ukrainian language is the language of education at all levels except for one or more subjects that are allowed to be taught in two or more languages, namely English or one of the other official languages of the European Union. The law stipulates a 3-year transitional period to come in full effect.[119][120] In February 2018, this period was extended until 2023.[121]

The law was condemned by PACE that called it "a major impediment to the teaching of national minorities".[122] The law also faced criticism from officials in Hungary, Romania and Russia[123] (Hungarian and Romanian are official languages of the European Union, Russian is not).[124][125] Ukrainian officials stressed that the new law complies fully with European norms on minority rights.[126]

The law does state that "Persons belonging to indigenous peoples of Ukraine are guaranteed the right to study in public facilities of preschool and primary education in the language of instruction of the respective indigenous people, along with the state language of instruction" in separate classes or groups.[120] PACE describes this as a significant curtailing of the rights of indigenous peoples carried out without consultations with their representatives.[122] On 27 June 2018, Ukrainian foreign minister Pavlo Klimkin stated that following the recommendation of the Venice Commission the language provision of the (September 2017) law on education will not apply to private schools and that every public school for national minorities "will have broad powers to independently determine which classes will be taught in Ukrainian or their native language".[127][128]

On 15 May 2019, Poroshenko signed the law "On provision of the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the State language".[129][130][d]

Religion

[edit]

Under Poroshenko the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine was created by the merging of the UOC-KP and the UAOC, and two members of the UOC-MP in a unification council which also elected Epiphanius I as its first primate. The 11 October 2018 announcement by Ecumenical Patriarchate that it would—among other things—grant autocephaly to a Ukrainian church is one of the reasons which created the Moscow–Constantinople schism when the Moscow Patriarchate severed full communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate on 15 October 2018.

Corruption

[edit]Corruption in Ukraine is a widespread problem; although there are signs that during Poroshenko presidency it decreased (thanks to the Prozorro digital system).[132] Poroshenko signed a decree to create the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine to comply with the requirements of the International Monetary Fund. Since 2015, the Bureau has sent 189 cases to court, but no one significant was convicted. The head of the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office reportedly coached suspects on how to avoid corruption charges.[133]

A November 2018 EU Commission report praised some of Ukraine's reforms during Poroshenko's presidency, such as in healthcare, pensions and public administration.[134] But judicial reforms were too slow, the report said, and "there have been only few convictions in high-level corruption cases so far".[134] It also stated that too often attacks on civil society activists went unpunished.[134]

During Poroshenko's 2019 campaign for reelection, a major scandal arose in which business partners of Poroshenko (but not Poroshenko himself) were accused of smuggling Russian components to Ukrainian defense factories at wildly inflated prices.[135][134]

Critics of Poroshenko stated he removed the jurisdiction of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine over records about off-the books payments to Paul J. Manafort, who lobbied on behalf of former Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych, and served as campaign manager for Donald Trump during his first presidential campaign.[136] Moreover, Poroshenko stripped of Ukrainian citizenship Mikheil Saakashvili who criticized him for not fighting Ukrainian corruption.[137]

On 11 April 2019, the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine was established and Poroshenko signed the decree appointing the judges during an official ceremony.[138]

LGBTQ rights

[edit]In 2015, Poroshenko spoke in defense of a planned gay pride march in Kyiv, calling it "the constitutional right of every citizen of Ukraine"; he said, "As far as the 'March of Equality' is concerned, I view it from both the perspective of a Christian and a pro-European president. I believe these are two completely compatible ideas."[139] Before Poroshenko's remarks, the nationalist Right Sector group had announced it would disrupt the march,[139] and Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko had called for its cancellation, saying it would be divisive at a time of war and risk "[creating] another confrontation in the centre of the capital".[140]

Foreign policy

[edit]

United States

[edit]On 7 December 2015, Poroshenko met with U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Kyiv to discuss Ukrainian-American cooperation.[141] He met U.S. President Donald Trump in June 2017; BBC News falsely accused him of paying Trump's lawyer Michael Cohen between 400,000 and 600,000 dollars to organize this meeting.[142][143] The BBC ended up having to state the allegation was untrue, apologizing to Poroshenko, deleting the article from its website, paying legal costs, and paying damages to Poroshenko.[144][145]

Russia

[edit]

In June 2014, Poroshenko forbade any cooperation with Russia in the military sphere.[146]

At the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe on 26 June 2014 Poroshenko stated that bilateral relations with Russia cannot be normalized unless Russia undoes its unilateral annexation of Crimea and returns its control of Crimea to Ukraine.[147]

On Poroshenko's June 2014 Peace plan for Eastern Ukraine, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov commented, "it looks like an ultimatum."[91]

On 26 August 2014, Poroshenko met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Minsk where Putin called on Ukraine not to escalate its offensive. Poroshenko responded by demanding Russia halt its supplying of arms to separatist fighters. He said his country wanted a political compromise and promised the interests of Russian-speaking people in eastern Ukraine would be considered.[148]

European Union

[edit]

The European Union (EU) and Ukraine signed the economic part of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement on 27 June 2014.[149] Poroshenko stated that the day was "Ukraine's most historic day since independence in 1991", describing it as a "symbol of faith and unbreakable will".[149] He saw the signing as the start of preparations for Ukrainian EU Membership.[149]

NATO

[edit]

At his speech at the opening session of the new parliament on 27 November 2014, Poroshenko stated that "we've decided to return to the course of NATO integration" because "the nonalignment status of Ukraine proclaimed in 2010 couldn't guarantee our security and territorial integrity".[150] The Ukrainian parliament on 23 December 2014 voted 303 to 8 to repeal a 2010 bill that had made Ukraine a non-aligned state in a bill submitted by Poroshenko.[151]

On 29 December 2014, Poroshenko vowed to hold a referendum on joining NATO.[152] On 22 September 2015, Poroshenko claimed that "Russia's aggressive actions" proved need for the enlargement of NATO and that the Ukrainian referendum on joining NATO would be held after "every condition for the Ukrainian compliance with NATO membership criteria" was met by "reforming our country".[153]

On 2 February 2017, in an interview with Funke Mediengruppe, Poroshenko announced he was planning a referendum on whether Ukraine should join NATO.[154]

International

[edit]Poroshenko was criticized by the Committee to Protect Journalists for signing a decree which banned 41 international journalists and bloggers from entering Ukraine for one year, being labeled as threats to national security.[155] The list includes three journalists from the BBC, and two Spanish journalists currently missing in Syria, all of whom previously covered the Ukraine crisis.[156]

In October 2015, Poroshenko visited the Kazakh capital of Astana, during which he told President Nursultan Nazarbayev that his country was Ukraine's "window to Asia" and vice versa.[157] During a visit to Gomel, Belarus in October 2018, he spoke to the Ukrainian community on the situation in Ukraine, saying that he does "not want Russia to use Belarus to get to our flank".[158]

2019 election

[edit]In the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election, Poroshenko received 24.5% of the second round votes, and was defeated by Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

There was no consensus in the expert community on a single reason why Poroshenko lost, although various reasons cited include:

- failure to successfully end the war;

- failure to stem corruption;

- several corruption scandals in which Poroshenko or people closely associated with him were involved (that included an investigation publicized during the election campaign, according to which associates of Poroshenko created a money laundering scheme in Ukroboronprom);

- a conflict with Ihor Kolomoyskyi which resulted in an anti-Poroshenko campaign by 1+1 Media Group (one of the largest media conglomerates in Ukraine);

- an information campaign supported by Russia against him;

- an overall fatigue from Ukrainian political elites;

- a presidential campaign that was focused almost exclusively on the right-wing and nationalistic population and exploited the patriotism topic at the expense of debates about social and economic situation; and

- lack of understanding and communication with Ukrainian people.[159][160][161][162][163][164][165]

Post-presidency (2019–present)

[edit]In the 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary election, Poroshenko was first on the party list of European Solidarity.[166]

Police raid at Poroshenko's headquarters and gym

[edit]On 20 December 2019, Ukrainian law enforcement raided both Poroshenko's party headquarters and gym on the orders of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Hidden cameras and recording devices were found inside the gym's smoke detectors and security alarms. According to the State Investigation Bureau, those were allegedly secretly recording and filming Poroshenko's gym clients, some of which are politicians and businessmen. Poroshenko and Ihor Kononenko, deputy head of Poroshenko's party, are both owners of said gym and could not be reached for comments. The raid was part of two ongoing criminal investigations which are focused on two concerns. First, the alleged theft of servers with classified information. Second, the alleged tax evasion and money laundering.[167]

Derkach recordings

[edit]In May 2020, Andrii Derkach, a former Ukrainian lawmaker who is aligned with a pro-Russian faction and has links to Russian intelligence, released edited fragments of private phone calls from several years between then U.S. Vice President Joe Biden (the then-presumptive Democratic nominee for U.S. president, elected president in 2020) and then-President Poroshenko. Derkach used the clips to make a series of accusations not supported by the tapes.[168] The taped conversations were consistent with official U.S. and European policy at the time and with public statements by Biden and Poroshenko.[168] Derkach had met with Rudolph W. Giuliani in December 2019.[168]

Derkach's maneuver raised questions about foreign interference in the 2020 U.S. elections, and echoed Russian government's interference into the 2016 election.[168] Biden's campaign and Poroshenko's political party European Solidarity described Derkach's act (which was publicized by the Russian state-controlled network RT) as a Russian attempt to harm Biden and disparage Ukraine.[168] In September 2020, the US Treasury Department sanctioned Derkach "for attempting to influence the U.S. electoral process", alleging he "has been an active Russian agent for over a decade, maintaining close connections with the Russian Intelligence Services".[169][170]

Anti-oligarch law

[edit]Two days after the passing of the anti-oligarch law, which seeks to curb the influence of Ukraine's wealthiest individuals, Poroshenko sold the TV channels Priamyi and 5 Kanal.[171]

Criminal case

[edit]On 20 December 2021, Poroshenko was accused of state treason, aiding terrorist organizations and financing terrorism due to allegedly organizing the purchase of coal from separatist-controlled areas of Ukraine together with pro-Russian politician Viktor Medvedchuk.[172] If convicted, he faces up to 15 years in prison.[173] Poroshenko denied the allegations, calling them "fabricated, politically motivated, and black PR directed against [Zelenskyy's] political opponents".[172] On 6 January 2022, a Ukrainian court seized Poroshenko's property.[174] On 15 January 2022, Poroshenko announced via a video message on Facebook: "I am returning to Ukraine on a flight from Warsaw at 09:10 a.m. on January 17… to defend Ukraine from Russian aggression", despite the case against him.[175][176]

Following his return to Ukraine, the prosecutor's office asked a court to either remand Poroshenko in pre-trial detention for two months, or oblige him to pay bail of ₴1 billion (US$37 million), wear an electronic bracelet, remain in Kyiv, and hand over his passport.[173][177][178] The court chose a third option ('personal commitment'), which is less strict than house arrest and doesn't involve paying bail.[179][180] According to this commitment, Poroshenko has to submit his passport to the authorities, not leave Kyiv or the Kyiv Oblast without first receiving permission from the court or the prosecutors office, and inform the authorities if his place of employment or residence change.[181]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]On 25 February 2022, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Poroshenko appeared on TV with a Kalashnikov rifle together with the civil defense forces on the streets of Kyiv. He also stated that he believed that "Putin will never conquer Ukraine, no matter how many soldiers he has, how many missiles he has, how many nuclear weapons he has... We Ukrainians are a free people, with a great European future. This is definitely so."[182][183]

On 12 March 2022, on the 17th day of the Russian invasion, Poroshenko personally handed over two civilian pickup trucks labeled "Bandera-Mobiles", in honor of Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera, to members of the 206th Territorial Defense Battalion of Kyiv. Both trucks were retrofitted with Soviet PKM machine guns, 450 bulletproof vests and decals of Bandera's face on the hood of both vehicles.[184]

At the end of May 2022, Poroshenko said he was not allowed to leave the country to visit Lithuania. Despite an official travel permit, he was refused entry to the border. Poroshenko wanted to attend the spring session of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly in Vilnius as a member of the Ukrainian delegation.[185] However, he was later allowed to leave Ukraine at the Polish border to attend a political meeting about the war.[186]

In July 2023, he criticized Volodymyr Zelenskyy for not getting a NATO entry promise from western leadership, during that year's NATO summit in Vilnius.[187]

In December 2023, Poroshenko was again prevented from leaving Ukraine, despite having an official travel permit signed by Verkhovna Rada speaker Ruslan Stefanchuk.[188]

In April 2024, Poroshenko announced his intention to participate in the upcoming Ukrainian presidential election.[189]

On 4 May 2024, Poroshenko was added to a wanted list by the Russian government on unspecified criminal charges, along with current president Zelenskyy and commander Oleksandr Pavliuk.[190][191]

In October 2024, Poroshenko donated US$1 million worth of FPV drones to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.[192]

Panama and Paradise Papers

[edit]Poroshenko was named in the Paradise Papers.[193] He set up an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands during the peak of the war in Donbas.[194] Leaked documents from the Panama Papers show he registered the company, Prime Asset Partners Ltd, on 21 August 2014. Records in Cyprus show him as the firm's only shareholder.[195] He said that he had done nothing wrong, and the legal firm, Avellum, overseeing the sale of Roshen, his confectionery company, said that "any allegations of tax evasion (were) groundless". The anti-corruption group Transparency International believes that the "creation of businesses while serving as president is a direct violation of the constitution". A similar explanation was given by current President Zelenskyy when he was named in the Pandora Papers.[196][197]

Personal life

[edit]

Poroshenko has been married to Maryna Perevedentseva, a cardiologist, since 1984.[16] The couple have four children together: Oleksii (born 1985), twins Yevheniia and Oleksandra (born 2000) and Mykhailo (born 2001).[16] Oleksii was a representative in the regional parliament of Vinnytsia Oblast.[17] In November 2014, he became a People's Deputy of Ukraine with 64.04% of votes in constituency No.12.[198] Poroshenko became a grandfather on the day of his presidential inauguration, 7 June 2014.[199]

His wife is actively involved in the activities of the Petro Poroshenko Charity Foundation.[16]

Poroshenko is a member of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.[38][17] Poroshenko has financed the restoration of its buildings and monasteries.[38] In high-level meetings he is often seen with a crucifix.[38]

In addition to his native language, Ukrainian, Poroshenko is fluent in Russian, English, and Romanian.[200]

Cultural and political image

[edit]

Poroshenko has been nicknamed the "Chocolate King" because of his ownership of Roshen.[36] Poroshenko has objected to being called an oligarch, saying: "Oligarchs are people who seek power in order to further enrich themselves. But I have long fought against bandits who are robbing our country and have destroyed free enterprise."[17]

After promising in his election campaign to sell his business assets when elected as the president of Ukraine, according to Poroshenko and Rothschild Wealth Management & Trust, after becoming President of Ukraine, he relinquished the management of his businesses, ultimately (in January 2016) to a blind trust.[13][23]

Potential implementation of martial law

[edit]During his speeches Poroshenko on numerous occasions called the war in East Ukraine a "Patriotic War",[202][203][204] yet did not initiate implementation of martial law, for which he was criticized on numerous occasions by politicians and the general public.[205][206] Poroshenko said it was necessary to realize the consequences of martial law for the country:

- It would restrict the supply of weaponry and items of dual assignment;

- The IMF does not provide funds to countries that are at war.[207]

A month later, the second statement was refuted by a head of the IMF's Ukrainian branch, Jerome Vacher, "As for the possible introduction of martial law, the IMF has no formal legal restrictions that impede continuation of mutual cooperation under such conditions. We have already worked with a number of countries where war conflicts of various intensity unfolded."[208]

On 5 February 2015, in his interview with the Spanish El País newspaper, Poroshenko stated that he would introduce martial law in the event of an escalation of the situation in Donbas, but that such a decision would limit democracy and civil liberties, as well as threaten the development of the economy.[209][210]

Martial law in Ukraine was introduced for 30 days in late November 2018, after the Kerch Strait incident.[211]

Connections with Dmytro Firtash

[edit]In April 2015, Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash at a court session about his extradition to the United States stated that at the Ukrainian presidential election he financially supported Poroshenko,[212] and Vitali Klitchko in the Kyiv city mayoral election.[212]

Mikheil Saakashvili

[edit]

On 29 May 2015, Poroshenko invited former President of Georgia and his friend Mikheil Saakashvili to help with conducting reforms in Ukraine and granted him Ukrainian citizenship.[213] The very next day after he became a citizen, on 30 May 2015, Saakashvili was appointed by the president as head (governor) of the Odesa Regional State Administration (see Governor of Odesa Oblast).[214]

On 26 July 2017 Poroshenko issued a decree[e] stripping Saakashvili of his Ukrainian citizenship, without providing any reason. According to The Economist, most observers saw Poroshenko's stripping Saakashvili of his citizenship "simply as the sidelining of a political rival" (Saakashvili started a political party Movement of New Forces to participate in upcoming elections).[216][137]

New year vacationing in 2018

[edit]In January 2018, journalists from Radio Free Europe reported that for Poroshenko's New Year's vacation starting 1 January 2018 in the Maldives, ten people who spent $500,000 to rent separate islands and the most expensive hotel in the country.[217][218] On 30 March 2018, Poroshenko submitted his income declaration. Poroshenko declared that he spent between 1.3 and 1.4 million UAH on this vacation—half what journalists had reported (some details about the president's vacation were classified).[219][218]

Awards

[edit] Ukraine: Order of Merit

Ukraine: Order of Merit Moldova: Order of the Republic

Moldova: Order of the Republic Poland: Order of the White Eagle

Poland: Order of the White Eagle Spain: Order of Civil Merit

Spain: Order of Civil Merit Ukraine: Medal of winner of Ukraine State Prize in Science and Technology

Ukraine: Medal of winner of Ukraine State Prize in Science and Technology Saudi Arabia: Order of King Abdulaziz[220]

Saudi Arabia: Order of King Abdulaziz[220] Lithuania: Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great

Lithuania: Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople: cross of Panagia Pammakaristos (5 January 2019)[221]

Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople: cross of Panagia Pammakaristos (5 January 2019)[221]- Orthodox Church of Ukraine: Order of St. Andrew Pervozvannyi[222][223] (Pervozvannyi meaning 'The First-Called')

Notes

[edit]- ^ In this name that follows Eastern Slavic naming customs, the patronymic is Oleksiiovych and the family name is Poroshenko.

- ^ Ukrainian: Петро Олексійович Порошенко, pronounced [peˈtrɔ olekˈs⁽ʲ⁾ijowɪtʃ poroˈʃɛnko]

- ^ The status of the Crimea and of the city of Sevastopol is currently under dispute between Russia and Ukraine; Ukraine and the majority of the international community consider the Crimea to be an autonomous republic of Ukraine and Sevastopol to be one of Ukraine's cities with special status, while Russia, on the other hand, considers the Crimea to be a federal subject of Russia and Sevastopol to be one of Russia's three federal cities.[80][83]

- ^ Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó said the law was "unacceptable" and part of an "anti-Hungarian policy" of Poroshenko.[131]

- ^ The decree was not made publicly available "in accordance with the legislation on personal data protection".[215]

References

[edit]- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the VII convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the III convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "People's Deputy of Ukraine of the V convocation". Official portal (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Ruzhinsky, Sergey (28 May 2014). Що варто знати про президента Петра Порошенка [What you should know about President Petro Poroshenko] (in Ukrainian). IPress.ua. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Petro Poroshenko's biography". Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Profile: Ukraine's President Petro Poroshenko". BBC News. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Poroshenko takes on Ukraine's oligarchs". Financial Times. 28 April 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Nathan Hodge (31 March 2019). "Ukraine election: Country's president is running against - Vladimir Putin". CNN. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Ukraine's Former President Sells TV Channels Following Passage Of 'Oligarch' Bill, Radio Free Europe; November 9, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ "Zelensky v oligarchs: Ukraine president targets super-rich". BBC News. 21 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Poroshenko's father died Archived 14 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (16 June 2020)

- ^ Матір та старший брат Петра Порошенка – білі плями біографії майбутнього Президента (in Ukrainian). Vinbazar. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g All In The Family: The Sequel Archived 29 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kyiv Post (7 October 2016)

- ^ Marcin Kosienkowski (2012). "Continuity and Change in Transnistria's Foreign Policy after the 2011 Presidential Elections". Academia.edu. p. 38. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Bănilă, Silviu (26 October 2014). "Petro Poroșenko VORBEȘTE în LIMBA ROMÂNĂ". Gândul (in Romanian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Tadeusz A. Olszański; Agata Wierzbowska-Miazga (28 May 2014). "Poroshenko, President of Ukraine". OSW, Poland. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Ukraine Election: The Chocolate King Rises". Spiegel Online. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Ukraine's tycoon Poroshenko confirms plans to sell assets". ITAR-TASS. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Saakashvili took over as head of the Odesa Regional State Administration, Deutsche Welle (30 May 2015)

- ^ (in Russian)/(website has automatic Google Translate option) Short bio Archived 5 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, LIGA

- ^ Abram Brown (31 March 2014). "The Willy Wonka of Ukraine Is Now The Leading Presidential Candidate". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko is not going to sell Channel 5 TV". Kyiv Post. 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b Roshen quits activity of its factory in Lipetsk Archived 20 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (20 January 2017)

- ^ Brian Bonner (8 March 2012). "Eight Ukrainians make Forbes magazine's list of world billionaires". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Billionaire No More: Ukraine President's Fortune Fades With War". Bloomberg Business. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Vitaliy Sych (30 October 2015). Порошенко растет, Ахметов падает – свежий Топ-100 самых богатых украинцев [Poroshenko grows, Akhmetov falls – Fresh Top 100 richest Ukrainians] (in Russian). Novoe Vremia. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Alle schimmige geldstromen belastingontwijkende President Oekraïne in één handig overzicht". 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Poroshenko lost billionaire status during presidency – media". unian.info. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Концерн "Укрпромінвест" оголосив про ліквідацію [Concern "Ukrprominvest" announced its liquidation] (in Ukrainian). UNIAN. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko says attempts underway to raid Pryamiy TV, denies ties with channel". News Agency. Interfax. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Komakha, O. "The Poroshenko's Bank is growing in 10 times faster (Банк Порошенко растет в 10 раз быстрее)". Minprom Information Agency. 16 October 2014

- ^ Kuzio, Taras; Frishberg, Alex (21 February 2008). "Ukrainian Political Update" (PDF). Frishberg & Partners, Attorneys at Law. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Петро Порошенко виходить на роботу [Poroshenko goes to work]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Results of voting in single-mandate constituencies". Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Retrieved 23 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Freedom House (2004). Nations in Transit 2004: Democratization in East Central Europe and Eurasia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 638–. ISBN 978-1-4617-3141-2. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b c "Profile: Ukraine 'chocolate king' President Poroshenko". BBC. 25 May 2014. Archived from the original on 26 May 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Hanly, Ken (25 May 2014). "Op-Ed: Petro Poroshenko the oligarch poised to become Ukraine president". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Luke Harding and Oksana Grytsenko (23 May 2014). "Chocolate tycoon heads for landslide victory in Ukraine presidential election". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.

"The Return of the Prodigal Son, Who Never Left Home". The Ukrainian Week. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

"Who will lead Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and where?". Den. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014. - ^ Alex Rodriguez (27 September 2005). "In Ukraine, old whiff of scandal in new regime". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Biography" (in Russian). Korrespondent.net. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006.

- ^ "Prosecutors Close Criminal Case Against Yushchenko's Close Ally". Kiev Ukraine News Blog. 21 October 2005. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Tammy M. Lynch (28 October 2005). "Independent standpoint on Ukraine:Dismissal of Prosecutor-General, Closure of Poroshenko Case Create New". ForUm. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Regions Party not to vote for Poroshenko's appointment Ukraine's foreign minister". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "Ukrainian president proposes Petro Poroshenko for foreign minister". Interfax-Ukraine. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

- ^ "Rada appoints Poroshenko Ukraine's foreign minister". Interfax-Ukraine. 9 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ By 240 out of 440 MPs registered in the session hall. In particular, 151 MPs of the Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko faction, 63 of the Our Ukraine-People's Self-Defense Bloc, 20 members of the Bloc of Volodymyr Lytvyn, one deputy of the Party of Regions, one member of the Communist Party faction, and four deputies not belonging to any faction voted for the nomination.

- ^ "Poroshenko put on Ukraine's NSCD". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 12 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko: Ukraine could join NATO in 1–2 years, with political, public will". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ "Mass Media:Poroshenko heads Ministry of Economy". UNIAN. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Regions Party: Poroshenko appointed economy minister, Kolobov appointed finance minister". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "President:Prime Minister nominated Petro Poroshenko for Minister of Economy". President.gov.ua. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Ukrainian president wants Poroshenko to head economic development and trade ministry". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Poroshenko appointed economic development and trade minister of Ukraine". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

"Poroshenko explains reasons behind accepting economy minister's post". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012. - ^ Порошенко Петр Алексеевич [Petr Aleksiyovych Poroshenko] (in Russian). LIGA.net. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Candidates single-mandate constituency № 12 Archived 5 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, RBC Ukraine

- ^ Полтавська область. Одномандатний виборчий округ №112 [Vinnytsia region. The single-mandate constituency № 12] (in Ukrainian). Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "Minister Poroshenko and his father registered as self-nominees for Vinnytsia region". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "Poroshenko not intending to join any faction". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

"Poroshenko fears uncontrolled economic situation in Ukraine due to foreign borrowing". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013. - ^ (in Ukrainian) Candidates single-mandate constituency № 16 Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, RBC Ukraine

- ^ "Poroshenko's father changes his mind to withdraw his candidacy from elections". UNIAN. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko appears set to join race for Kyiv mayor". Ukraine Business Online. 12 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Interview with Ukrainian presidential candidate Petro Poroshenko". The Washington Post. 25 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: Speaker Oleksandr Turchynov named interim president". BBC News. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

"Ukraine protests timeline". BBC News. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2014. - ^ Главная | Центр соціальних та маркетингових досліджень SOCIS Archived 21 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Socis.kiev.ua. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Klitschko will run for mayor of Kyiv". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Klitschko believes only presidential candidate from democratic forces should be Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Colin Freeman (29 March 2014). "Petro Poroshenko, the billionaire chocolate baron hoping to become Ukraine's next president". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: former boxer Vitaliy Klitschko ends presidential bid and backs Poroshenko". Euronews. 29 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko ready to sell Roshen if elected president". Interfax-Ukraine. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Question of Ukraine's membership of NATO may split country – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "Poroshenko Declares Victory in Ukraine Presidential Election". The Wall Street Journal. 25 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Polska Razem czarnym koniem? Mocne słowa Gowina" [Polish Total black horse? Strong words Gowin] (in Polish). 12 April 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko wins presidential election with 54.7% of vote – CEC". Interfax-Ukraine. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine talks set to open without pro-Russian separatists". The Washington Post. 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine elections: Runners and risks". BBC News. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Q&A: Ukraine presidential election". BBC News. 7 February 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko wins presidential election with 54.7% of vote – CEC". Radio Ukraine International. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

Внеочередные выборы Президента Украины [Results election of Ukrainian president] (in Russian). Телеграф. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014. - ^ "New Ukrainian president will be elected for 5-year term – Constitutional Court". Interfax-Ukraine. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko: 'No negotiations with separatists'". Deutsche Welle. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Ukraine crisis timeline". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Poroshenko promises calm 'in hours' amid battle to control Donetsk airport". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "EU & Ukraine 17 April 2014 FACT SHEET" (PDF). European External Action Service. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Gutterman, Steve; Polityuk, Pavel (18 March 2014). "Putin signs Crimea treaty, will not seize other Ukraine regions". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ "In Ukrainian election, chocolate tycoon Poroshenko claims victory". The Washington Post. 25 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014.

- ^ Lukas Alpert (29 May 2014). "Petro Poroshenko to Be Inaugurated as Ukraine President June 7". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

"Rada decides to hold inauguration of Poroshenko on June 7 at 1000". Interfax-Ukraine. 3 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

"Poroshenko sworn in as Ukrainian president". Interfax-Ukraine. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014. - ^ a b c d e f g "Ukraine president vows not to give up Crimea". The Guardian. theguardian.com. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014.

"Ukraine's Poroshenko sworn in and sets out peace plan". BBC News. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.

"Excerpts from Poroshenko's speech". BBC News Online. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014.

"Ukraine's President Poroshenko pushes for peace at inauguration". Euronews. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014.

"Poroshenko offers escape for rebels but no compromise over weapons". Euronews. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

Промова президента України під час церемонії інавгурації. Повний текст [Speech by President of Ukraine during the inauguration ceremony. Full text]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. - ^ a b На інавгурацію Порошенка прибудуть делегації з 56 країн [At the inauguration Poroshenko come delegations from 56 countries]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine: International recognition for President Poroshenko". Euronews. 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Тимошенко: президент Порошенко – потужний фактор стабільності [Tymoshenko: President Poroshenko – a powerful factor of stability]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko doesn't rule out roundtable in Donetsk involving parties to conflict". Interfax-Ukraine. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Poroshenko warns of 'detailed Plan B' if Ukraine ceasefire fails". Al Jazeera. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Amendments to Ukraine's Constitution to be tabled in parliament this week – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko suggests granting status of regions to Crimea, Kyiv, Sevastopol, creating new political subdivision of 'community'". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Authorities in Ukrainian regions may be allowed to determine status of national minority languages". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Ukrainian president proposes to appoint representatives to regions". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine's Poroshenko names new defence chiefs in shake-up". Reuters. 3 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Documents signed in Minsk don't envision federalization, autonomy for Donbas – Poroshenko Archived 24 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine". Interfax-Ukraine. 12 February 2015.

- ^ Poroshenko rules out federalization of Ukraine Archived 24 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Interfax-Ukraine. 23 June 2015.

Ukraine to remain unitary state after constitution is amended – Poroshenko Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2015. - ^ Semi-presidential form of government is optimal for Ukraine – Poroshenko Archived 2 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Interfax-Ukraine. 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b Poroshenko Unveils Constitutional Changes Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe (1 July 2015)

- ^ "Ukraine President Poroshenko Calls Snap General Election". Bloomberg News. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: President calls snap vote amid fighting". BBC News. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Ukrainian President dissolves Parliament, announces early elections Archived 31 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, United Press International (25 August 2014)

"Ukraine's Petro Poroshenko Dissolves Parliament, Sets Election Date". The Moscow Times. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014.

President's address on the occasion of early parliamentary elections of 26 October, Presidential Administration of Ukraine (25 August 2014) - ^ "Poroshenko hopes early parliamentary elections in Ukraine will take place in October". Interfax-Ukraine. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko hopes for early parliamentary elections in Ukraine this fall – presidential envoy". Interfax-Ukraine. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ "In Ukrainian election, chocolate tycoon Poroshenko claims victory". The Washington Post. 25 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ "Poroshenko wants coalition to be formed before parliamentary elections". Interfax-Ukraine. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

"Solidarity Party to be renamed Bloc of Petro Poroshenko – congress". Interfax-Ukraine. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. - ^ Порошенко і порожнеча (in Ukrainian). 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ "Bloc of Petro Poroshenko to change name". Ukrinform.net. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Ukraine has no ambitions to become nuclear power again – Poroshenko Archived 14 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (13 December 2014)

- ^ a b c Poroshenko signed the laws about decommunization Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes Archived 19 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine. 15 May 20

Poroshenko: Time for Ukraine to resolutely get rid of Communist symbols Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, UNIAN. 17 May 2015

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (14 April 2015) - ^ Порошенко: час очистити Україну від комуністичних символів [Poroshenko: time to clear Ukraine of communist symbols]. BBC Ukrainian (in Ukrainian). 17 May 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Ukraine to rewrite Soviet history with controversial 'decommunisation' laws Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian. 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Poroshenko to Sell Roshen If Elected Ukrainian President: Bild Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Bloomberg. 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Powerful Ukrainian Governor Kolomoyskiy Resigns". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "IN UKRAINE THERE WILL BE NO MORE OLIGARCHS – POROSHENKO". 5.ua. 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Poroshenko enacts law granting fighters for Ukraine's independence in 20th century combatant status". UNIAN. 23 December 2018. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Language quotas for Ukraine radio shows". BBC News. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "New education law becomes effective in Ukraine". unian.info. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Про освіту Archived 14 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine | від 5 September 2017 № 2145-VIII (Сторінка 1 з 7)

- ^ "Ukraine agrees to concessions to Hungary in language row". unian.info. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ a b "PACE – Resolution 2189 (2017) – The new Ukrainian law on education: a major impediment to the teaching of national minorities' mother tongues". assembly.coe.int.

- ^ Wesolowsky, Tony (19 July 2022). "Ukrainian Language Bill Facing Barrage Of Criticism From Minorities, Foreign Capitals". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ "Consolidated version of Regulation No 1 determining the languages to be used by the European Economic Community" (PDF). Europa. European Union. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ "Languages of Europe – Official EU languages". European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Hungary in language dispute with Ukraine". BBC News. 10 October 2017 – via bbc.com.

- ^ Hungary realizes Ukraine not to change education law – Klimkin Archived 14 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, UNIAN (27 June 2018)

- ^ Debate on language provisions of Ukraine's education law not over – minister Archived 14 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, UNIAN (12 January 2018)

- ^ "Poroshenko enacts Ukraine's language law". www.unian.info. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "President signed the law on the official language: Language is a platform on which the nation and state are built". Official website of the President of Ukraine. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Глава МЗС Угорщини розкритикував закон про мову, покладає надії на Зеленського [Hungarian FM criticized language law, puts hopes on Zelensky]. Yevropeiska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 26 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ 'Corruption in Ukraine has to be stopped', BBC News (20 March 2019)

- ^ "Want to Know What's Next in Russian Election Interference? Pay Attention to Ukraine's Elections". Lawfare. 28 March 2019.