Philip Dunne (writer)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

Philip Dunne | |

|---|---|

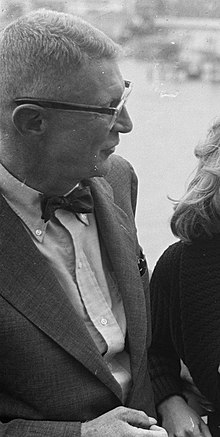

Philip Dunne (1961) | |

| Born | Philip Ives Dunne February 11, 1908 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | June 2, 1992 (aged 84) Malibu, California, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Screenwriter, film director and producer |

Philip Ives Dunne (February 11, 1908 – June 2, 1992) was an American screenwriter, film director and producer, who worked prolifically from 1932 until 1965. He spent the majority of his career at 20th Century Fox. He crafted well regarded romantic and historical dramas, usually adapted from another medium. Dunne was a leading Screen Writers Guild organizer and was politically active during the "Hollywood Blacklist" episode of the 1940s–1950s. He is best known for the films How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), The Robe (1953) and The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965).[1]

Dunne received two Academy Award nominations for screenwriting: How Green Was My Valley (1941) and David and Bathsheba (1951). He also received a Golden Globe nomination for his 1965 screen adaptation of Irving Stone's novel The Agony and the Ecstasy, as well as several peer awards from the Writers Guild of America (WGA), including the Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement.

Many notable directors worked with Dunne's screenplays, including Carol Reed, John Ford, Jacques Tourneur, Elia Kazan, Otto Preminger, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and Michael Curtiz, among others.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Dunne was born in New York City, the son of Chicago syndicated columnist and humorist Finley Peter Dunne and Margaret Ives Abbott, the first American woman to win an Olympic medal and the daughter of the Chicago Tribune's book reviewer and novelist, Mary Ives Abbott.

Although a Roman Catholic, he attended Middlesex School (1920–1925) and Harvard University (1925–1929). Immediately after graduation, he boarded a train for Hollywood for his health and to seek work.[2]

First screenplays

[edit]Dunne was not initially interested in working in the film industry but that was the first place he got a job. Via a recommendation from a friend of his brother he obtained work at Fox as a reader at $35 a week.[2] Also among readers at the time was Leonard Spigelgass. Dunne later recalled:

We got nothing but the worst stuff; all the good books and plays went through the New York readers’ department. We got the pathetic originals written by out-of-work screenwriters. I kept seeing ways that I thought I could improve them. I'd write a synopsis, and I'd make it better. I couldn't help it. It would be an obvious thing that the guy had missed. And when you learn to synopsize a story, you learn to construct it. At the same time, I was moonlighting writing short stories, so all these things came together."[3]

In 1931, Dunne was fired from Fox after less than a year at the studio in a cost-cutting move. He was briefly under contract at MGM, writing a comedy for them, but was unhappy with his work and resigned after handing in his first draft. This script was subsequently filmed as Student Tour (1934), which Dunne never saw.[4][5]

Dunne also worked uncredited on Me and My Gal (1932).[citation needed]

Career progress

[edit]The first important screenplay of Dunne's career was The Count of Monte Cristo (1934), produced by Edward Small. Dunne was brought on to the project after the novel had been distilled to a treatment by director Rowland V. Lee and Dan Totheroh, and Dunne helped finesse the script into scenes and did the dialogue. Dunne later credited Lee as an important mentor for him.[6]

Small kept Dunne on to work on the script for The Melody Lingers On (1935).[5] He was also credited for Helldorado (1935), the latter at Fox for Jesse Lasky, another early mentor.

He did some minor uncredited work on Under Pressure (1935) and Magnificent Obsession (1935).

Dunne received a lot of acclaim for his adaptation of The Last of the Mohicans (1936) for Small which he wrote with John L. Balderstone. Dunne claimed the script was hurt by later rewrites from another writer, but the script, rather than the original novel, formed the basis of the 1992 film version.[5]

For Universal he wrote Breezing Home (1937) which he later said was the first of what he considered only four original screenplays he would write in his career.[3]

20th Century Fox

[edit]After working for various studios, he moved to 20th Century Fox in 1937, where he would remain for 25 years (excepting 4 years civilian war service during World War II), scripting 36 films in total and directing 10. He also produced several of his later films.

His first assignment at Fox was Lancer Spy (1937), with George Sanders. He then did three films in collaboration with Julien Josephson which established him as one of the leading writers at the studio: Suez (1938), Stanley and Livingstone (1939), and The Rains Came (1939).

Alone Dunne wrote Swanee River (1939), and Johnny Apollo (1940) (rewriting Rowland Brown's draft).

He wrote How Green Was My Valley (1941) originally developed with William Wyler then taken over by John Ford.[7] He also wrote Son of Fury: The Story of Benjamin Blake (1942).

World War II

[edit]From 1942 to 1945, Dunne was the Chief of Production for the Motion Picture Bureau, U.S. Office of War Information, Overseas Branch. He wrote films such as Salute to France (1943).[2]

Notably, he produced the non-fiction short The Town (1944), directed by Josef von Sternberg, which has received some critical acclaim.[8]

Postwar career

[edit]Dunne returned to Fox after the war and quickly re-established himself as one of the studio's leading writers with credits including The Late George Apley (1947), and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947).

He wrote Forever Amber (1947) in collaboration with Ring Lardner Jr and wrote Escape (1948) and The Luck of the Irish (1948). He revised Dudley Nichols' script for Pinky (1949).[4]

In 1949 he and Otto Preminger were working on a film The Far East Story which was never made.[9]

Dunne moved into spectacles with David and Bathsheba (1951), based on the story in the Bible but which Dunne considered his second "original". It was a huge hit. Zanuck put Dunne on Queen of Sheba but it was never made.[10]

He also wrote Anne of the Indies (1951) and Lydia Bailey (1952).[citation needed]

Producer

[edit]Dunne turned producer with Way of a Gaucho (1952) which he also wrote.[11][12] As a writer only he worked on The Robe (1953), the first movie in CinemaScope and a huge success. Dunne had enjoyed writing David and Bathsheba but said working on The Robe was "a chore" which he only did "as a favor to Zanuck".[13]

He was announced for a film The Story of Jezebel which was not made. Dunne wrote the sequel to The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), his third original, which was also a hit.

However another spectacle Dunne wrote (from a draft by Casey Robinson), The Egyptian (1954), was a box-office disappointment. Dunne says he acted as an unofficial producer on this film.[13]

Director

[edit]Dunne was assigned to produce Prince of Players (1955) from a script by Moss Hart. When he could not find a director he was happy with, Darryl F. Zanuck suggested Dunne to do the job himself.[14]

Dunne later said "I started directing too late and, no question, at the wrong time. Twentieth Century Fox, the studio system, were falling apart. The boat had sailed."[15]

Dunne wrote, produced and directed The View from Pompey's Head (1955). He wrote and directed Hilda Crane (1956). That was produced by Herbert Swope who also produced Three Brave Men (1957) which Dunne wrote and directed.[16]

He directed and did some writing on In Love and War (1958), a war time drama, featuring many of the studio's young contract players. Edward Anhalt wrote it and Jerry Wald produced.[17]

Dunne wrote and directed two films for producer Charles Brackett: Ten North Frederick (1958) with Gary Cooper, and Blue Denim (1959).

Later films

[edit]In 1961, he directed Wild in the Country, starring Elvis Presley, from a screenplay by Clifford Odets and produced by Wald.[citation needed]

In 1962, he directed Lisa, based on the novel The Inspector by Jan de Hartog and featuring Stephen Boyd and Dolores Hart, which was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Picture – Drama. Dunne did not write it.[18][6]

Dunne worked on The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) as a writer only.[19] Although based on a novel by Irving Stone, Dunne later said he considered this an original. "I called it Quirt and Flagg in the Sistine Chapel", he said later.[20]

He wrote and directed Blindfold (1966), at Universal. It was his last feature. He was reportedly working on an adaptation of The Consort a novel by Anthony Hextall Smith, but it was never made.[21]

The 1992 film The Last of the Mohicans, directed by Michael Mann and starring Daniel Day-Lewis, was based on Dunne's 1936 screenplay of the Fenimore Cooper novel.[citation needed]

Other writing

[edit]In addition to screenwriting, Dunne wrote syndicated newspaper articles and was a contributor to The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly magazines.[citation needed]

He wrote speeches for various Democratic politicians such as Adlai Stevenson.[4]

He also wrote a stage play, Mr. Dooley's America (1976), based on his father's humor, and another, Politics (1980).[citation needed]

His books include Mr Dooley Remembers (1963) and Take Two: A Life in Movies and Politics (1980). His short stories appeared in the New Yorker and his essays were regular features of Time, the Los Angeles Times, and the Harvard Review.[22]

Awards

[edit]He was a winner of the Laurel Award (1962) and the Valentine Davies Award (1974).

The week before he died he was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Writers Guild.[4]

Dunne has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, in front of 6725 Hollywood Boulevard, just west of Las Palmas Ave.

Politics

[edit]Dunne was a co-founder of the Screen Writers Guild and served as vice-president of its successor, the Writers Guild of America, from 1938 to 1940. He later served on the Board of Governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) from 1946 to 1948.[citation needed]

Before World War II, he was a member of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, a group founded in May 1940 that advocated military materiel aid to Britain as the best way to keep the United States out of the war.[citation needed]

Philip Dunne and the Hollywood Blacklist

[edit]Dunne was a key participant in the Hollywood Blacklist episode of the 1940s and 1950s. In 1947 he co-founded the Committee for the First Amendment with John Huston and William Wyler in response to hearings held by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Dunne, Huston, and Wyler, along with fellow members Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Danny Kaye, and Gene Kelly, appeared before HUAC in Washington, D.C. in October 1947, protesting HUAC's activities and methods. Dunne was never subpoenaed or blacklisted himself, nor was he accused of any Communist Party affiliations.[23]

As a writer and director, Dunne frequently worked with others who either were, had been, or would become blacklisted, including Ring Lardner Jr., Clifford Odets, Albert Maltz, and Marsha Hunt. Additionally, Dunne was a character witness for Dalton Trumbo at the latter's trial for contempt of Congress.[citation needed]

The original credits for The Robe (1953) gave Dunne the sole screenplay credit, when in fact Hollywood Ten member Albert Maltz had made significant contributions. In 1997, the WGA restored full writing credits to blacklisted writers whose names were left out of films they worked on. The following is from the WGA's "Blacklisted Writers Receive Credit" press release of April 2, 1997:

In the case of The Robe there was an extraordinary amount of information gathered to indicate that Maltz was entitled to shared screenplay credit. In addition, Philip Dunne did not believe he deserved sole screenplay credit but it was not until many years later that he learned that a blacklisted writer had worked on the project. Amanda Dunne, Philip's widow, confirms that Philip would have been happy to share screenplay credit with Maltz.

Dunne's political stance was decidedly liberal and reformist, but he was also determinedly anti-Communist. His involvement in the Committee for the First Amendment can arguably be read as just that—support for Constitutional free speech against a government entity (HUAC) that, to Dunne, seemed determined to usurp those rights. At various times dating to before the Second World War, he clashed with fellow members of the Screen Writers Guild who he felt were "pro-Stalin" Communists. Dunne's anti-Communist leanings would seem to be verified by his uninterrupted employment as a screenwriter on major Hollywood productions throughout the blacklist period, despite his quite vocal denunciation of HUAC.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Dunne married the former Amanda Duff (1914–2006) on July 13, 1939.[24] They had three children.[citation needed]

Quotes

[edit]- "Never in all my years in this chancy and unstable profession did I ever realize that I was sleepwalking along a precipice. I ignored the fact that the rate of professional mortality among screen writers is extremely high...It wasn't courage or arrogance or insensitivity; I suspect it was the irascible Horatio Alger in my blood. If I had it to do all over again I would perish of sheer fright."

- "All over town the industrious communist tail wagged the lazy liberal dog."

- "Had I known it was the Golden Age of Hollywood, I would have enjoyed it more."

Selected filmography

[edit]- The Count of Monte Cristo (1934, screenplay with Rowland V. Lee and Dan Totheroh)

- Student Tour (1934, screenplay)

- Helldorado (1935, screenplay)

- The Melody Lingers On (1936, screenplay)

- The Last of the Mohicans (1936, screenplay)

- Breezing Home (1937, screenplay)

- Lancer Spy (1937, screenplay)

- Suez (1938, screenplay)

- Stanley and Livingstone (1939, screenplay with Julien Josephson)

- The Rains Came (1939, screenplay)

- Swanee River (1939, screenplay)

- Johnny Apollo (1940, screenplay with Rowland Brown)

- How Green Was My Valley (1941, screenplay)

- Son of Fury (1942, screenplay)

- The Late George Apley (1947, screenplay)

- The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947, screenplay)

- Forever Amber (1947, screenplay with Ring Lardner Jr.)

- Escape (1948, screenplay)

- The Luck of the Irish (1948, screenplay)

- Pinky (1949, screenplay with Dudley Nichols)

- Anne of the Indies (1951, screenplay)

- David and Bathsheba (1951, screenplay)

- Lydia Bailey (1952, screenplay)

- Way of a Gaucho (1952, screenplay, producer)

- The Robe (1953, screenplay with Albert Maltz)

- Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954, screenplay)

- The Egyptian (1954, screenplay with Casey Robinson)

- Prince of Players (1955, director, producer)

- The View from Pompey's Head (1955, screenplay, director, producer)

- Hilda Crane (1956, screenplay, director)

- Three Brave Men (1956, screenplay and director)

- Ten North Frederick (1958, screenplay and director)

- In Love and War (1958, director)

- Blue Denim (1959, screenplay, director)

- Wild in the Country (1961, director)

- Lisa (1962, director)

- The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965, screenplay with Carol Reed)

- Blindfold (1966, screenplay and director)

References

[edit]- Contemporary Authors: Philip Dunne, Thomson Gale, 2004

- Philip Dunne, Take Two: A Life in Movies and Politics, McGraw-Hill, 1980 (ISBN 0-87910-157-1)

- McGilligan, Patrick (1986). Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood's Golden Age. University of California Press.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dunne, Philip (December 21, 1980). "MOVIES: PHILIP DUNNE: A CHAPTER FROM A CINEMATIC LIFE". Los Angeles Times. p. s58.

- ^ a b c "Philip Dunne;Obituary". The Times. London. June 8, 1992.

- ^ a b McGilligan p 156

- ^ a b c d Folkart, Burt A. (June 4, 1992). "Philip Dunne, Writer-Director Who Opposed Blacklists, Dies". Los Angeles Times (Home ed.). p. 1.

- ^ a b c Server p 96

- ^ a b MURRAY SCHUMACH (April 3, 1962). "DIRECTORS CHIDED FOR FILM WRITING: Philip Dunne Urges That Scenarists Be on Sets Best-Known Scripts Used One Line". New York Times. p. 43.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (April 2, 1991). "How Collaborative Was Their Project Movies: Philip Dunne, screenwriter for 'How Green Was My Valley", recalls conflicts and compromises with director John Ford and producer Darryl Zanuck". Los Angeles Times (Home ed.). p. 5.

- ^ "Screenwriter Philip Dunne, 84; founded guild, fought blacklist". Boston Globe. June 9, 1992. p. 95.

- ^ THOMAS F. BRADY (February 28, 1949). "'SWORD IN DESERT' TO STAR ANDREWS: Paul Christian's Illness Causes Change in the Cast of U-I Film About Palestine". New York Times. p. 16.

- ^ THOMAS M. PRYOR (September 17, 1951). "ZANUCK WILL FILM 'QUEEN OF SHEBA': Success of Fox's 'David and Bathsheba' Has Researchers at Studio Reading Bible". New York Times. p. 17.

- ^ HOWARD THOMPSON (August 26, 1951). "BY WAY OF REPORT: The South American Way At Fox—Disney Docket CRYSTAL GAZER: AGENDA: OF GANDHI". New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ "Drama: Dore Schary Picture List Rated Notable". Los Angeles Times. January 26, 1951. p. A8.

- ^ a b McGilligan p 164

- ^ HOWARD THOMPSON (June 8, 1966). "OF PICTURES AND PEOPLE: Blueprint for 'Prince of Players' – A Chinese 'G. W. T. W.' – Other Items". New York Times. p. d11.

- ^ Lee Server (1987). Screenwriter: Words Become Pictures. p. 109.

- ^ "Joi Lansing Now Invited to England". Los Angeles Times. April 9, 1956. p. B9.

- ^ Rule, Sheila (June 4, 1992). "Philip Dunne, 84, Screenwriter And an Opponent of Blacklisting". New York Times. p. B.12.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (March 5, 1962). "Piped Theater TV Called Death Knell: Philip Dunne Survives 25 Years of Shake-ups at Fox". Los Angeles Times. p. C15.

- ^ MURRAY SCHUMACH Special to The (February 14, 1963). "FOX STUDIO BACK IN PRODUCTION: Film Work Resumes After Long Inactivity Film Set for Spring Other Scripts Prepared". New York Times. p. 5.

- ^ McGilligan p156

- ^ Kimmis Hendrick. The (June 10, 1966). "Dunne: writer who directs: Urgent advice". Christian Science Monitor. p. 4.

- ^ Freeman, David (May 3, 1992). "A Wide Angle on Hollywood TAKE TWO: A Life in Movies and Politics, By Philip Dunne (Limelight Editions: $17.95, paper; 405 pp.)". Los Angeles Times (Home ed.). p. 2.

- ^ "Noted screenwriter Philip Dunne, 84". Chicago Tribune. June 5, 1992. p. A8.

- ^ "Philip Dunne Weds Miss Duff". New York Times. July 16, 1939. p. 32.

KSF

KSF